User login

Psychotherapy for psychiatric disorders: A review of 4 studies

Psychotherapy is among the evidence-based treatment options for treating various psychiatric disorders. How we approach psychiatric disorders via psychotherapy has been shaped by numerous theories of personality and psychopathology, including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, systems, and existential-humanistic approaches. Whether used as primary treatment or in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy has played a pivotal role in shaping psychiatric disease management and treatment. Several evidence-based therapy modalities have been used throughout the years and continue to significantly improve and impact our patients’ lives. In the armamentarium of treatment modalities, therapy takes the leading role for several conditions. Here we review 4 studies from current psychotherapy literature; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-4

1.

Panic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 3.7% in the general population. Three treatment modalities recommended for patients with panic disorder are psychological therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and self-help. Among the psychological therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used.1

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder has been proven to be an efficacious and impactful treatment. For panic disorder, CBT may consist of different combinations of several therapeutic components, such as relaxation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and/or in vivo exposure. It is therefore important, both theoretically and clinically, to examine whether specific components of CBT or their combinations are superior to others for treating panic disorder.1

Pompoli et al1 conducted a component network meta-analysis (NMA) of 72 studies in order to determine which CBT components were the most efficacious in treating patients with panic disorder. Component NMA is an extension of standard NMA; it is used to disentangle the treatment effects of different components included in composite interventions.1

The aim of this study was to determine which specific component or combination of components was superior to others when treating panic disorder.1

Study design

- Researchers reviewed 2,526 references from Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central and selected 72 studies that included 4,064 patients with panic disorder.1

- The primary outcome was remission of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the short term (3 to 6 months). Remission was defined as achieving a score of ≤7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).1

- Secondary outcomes included response (≥40% reduction in PDSS score from baseline) and dropout for any reason in the short term.1

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Using component NMA, researchers determined that interoceptive exposure and face-to-face setting (administration of therapeutic components in a face-to-face setting rather than through self-help means) led to better efficacy and acceptability. Muscle relaxation and virtual reality exposure corresponded to lower efficacy. Breathing retraining and in vivo exposure improved treatment acceptability, but had small effects on efficacy.1

- Based on an analysis of remission rates, the most efficacious CBT incorporated cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure. The least efficacious CBT incorporated breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, in vivo exposure, and virtual reality exposure.1

- Application of cognitive and behavioral therapeutic elements was superior to administration of behavioral elements alone. When administering CBT, face-to-face therapy led to better outcomes in response and remission rates. Dropout rates occurred at a lower frequency when CBT was administered face-to-face when compared with self-help groups. The placebo effect was associated with the highest dropout rate.1

Conclusion

- Findings from this meta-analysis have high practical utility. Which CBT components are used can significantly alter CBT’s efficacy and acceptability in patients with panic disorder.1

- The “most efficacious CBT” would include cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure delivered in a face-to-face setting. Breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, and virtual reality may have a minimal or even negative impact.1

- Limitations of this meta-analysis include the high number of studies used for the data analysis, complex statistical analysis, inability to include unpublished studies, and limited relevant studies. A future implication of this study is the consideration of formal methodology based on the clinical application of efficacious CBT components when treating patients with panic disorder.1

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

Psychotherapy is also a useful modality for treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Sloan et al2 compared brief exposure-based treatment with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for PTSD.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of PTSD and acute stress disorder recommend the use of individual, trauma-focused therapies that focus on exposure and cognitive restructuring, such as prolonged exposure, CPT, and written narrative exposure.5

Continue to: One type of written narrative...

One type of written narrative exposure treatment is written exposure therapy (WET), which consists of 5 sessions during which patients write about their trauma. The first session is comprised of psychoeducation about PTSD and a review of treatment reasoning, followed by 30 minutes of writing. The therapist provides feedback and instructions. Written exposure therapy requires less therapist training and less supervision than prolonged exposure or CPT. Prior studies have suggested that WET can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in various trauma survivors.2

Although efficacious for PTSD, WET had not been compared with CPT, which is the most commonly used first-line treatment of PTSD. The aim of this study was to determine whether WET is noninferior to CPT.2

Study design

- In this randomized noninferiority clinical trial conducted in Boston, Massachusetts from February 28, 2013 to November 6, 2016, 126 veterans and non-veteran adults were randomized to WET or CPT. Participants met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD and were taking stable doses of their medications for at least 4 weeks.2

- Participants assigned to CPT (n = 63) underwent 12 sessions, and participants assigned to WET (n = 63) received 5 sessions. Cognitive processing therapy was conducted over 60-minute weekly sessions. Written exposure therapy consisted of an initial session that was 60 minutes long and four 40-minute follow-up sessions.2

- Interviews were conducted by 4 independent evaluators at baseline and 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks. During the WET sessions, participants wrote about a traumatic event while focusing on details, thoughts, and feelings associated with the event.2

- Cognitive processing therapy involved 12 trauma-focused therapy sessions during which participants learn how to become aware of and address problematic cognitions about the trauma as well as thoughts about themselves and others. Between sessions, participants were required to write 2 trauma accounts and complete other assignments.2

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was change in total score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). The CAPS-5 scores for participants in the WET group were noninferior to those for participants in the CPT group at all assessment points.2

- Participants did not significantly differ in age, education, income, or PTSD severity. Participants in the 2 groups did not differ in treatment expectations or level of satisfaction with treatment. Individuals assigned to CPT were more likely to drop out of the study: 20 participants in the CPT group dropped out in the first 5 sessions, whereas only 4 dropped out of the WET group. The dropout rate in the CPT group was 39.7%. Improvements in PTSD symptoms in the WET group were noninferior to improvements in the CPT group.2

- Written exposure therapy showed no difference compared with CPT in decreasing PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that PTSD symptoms can decrease with a smaller number of shorter therapeutic sessions.2

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated noninferiority between an established, commonly used PTSD therapy (CPT) and a version of exposure therapy that is briefer, simpler, and requires less homework and less therapist training and expertise. This “lower-dose” approach may improve access for the expanding number of patients who require treatment for PTSD, especially in the Veterans Affairs system.2

- In summary, WET is well tolerated and time-efficient. Although it requires fewer sessions, WET was noninferior to CPT.2

Continue to: Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual...

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive, family-based, home-based intervention for young people with serious antisocial behavior. It has been found effective for childhood conduct disorders in the United States. However, previous studies that supported its efficacy were conducted by the therapy’s developers and used noncomprehensive comparators, such as individual therapy. Fonagy et al3 assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MST vs management as usual for treating adolescent antisocial behavior. This is the first study that was performed by independent investigators and used a comprehensive control.3

Study design

- This 18-month, multisite, pragmatic, randomized controlled superiority trial was conducted in England.3

- Participants were age 11 to 17, with moderate to severe antisocial behavior. They had at least 3 severity criteria indicating difficulties across several settings and at least one of the 5 inclusion criteria for antisocial behavior. Six hundred eighty-four families were randomly assigned to MST or management as usual, and 491 families completed the study.3

- For the MST intervention, therapists worked with the adolescent’s caregiver 3 times a week for 3 to 5 months to improve parenting skills, enhance family relationships, increase support from social networks, develop skills and resources, address communication problems, increase school attendance and achievement, and reduce the adolescent’s association with delinquent peers.3

- For the management as usual intervention, management was based on local services for young people and was designed to be in line with current community practice.3

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in out-of-home placements at 18 months. The secondary outcomes were time to first criminal offense and the total number of offenses.3

- In terms of the risk of out-of-home placement, MST had no effect: 13% of participants in the MST group had out-of-home placement at 18 months, compared with 11% in the management-as-usual group.3

- Multisystemic therapy also did not significantly delay the time to first offense (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.33). Also, at 18-month follow-up, participants in the MST group had committed more offenses than those in the management-as-usual group, although the difference was not statistically significant.3

- Parents in the MST group reported increased parental support and involvement and reduced problems at 6 months, but the adolescents’ reports of parenting behavior indicated no significant effect for MST vs management as usual at any time point.3

Conclusion

- Multisystemic therapy was not superior to management as usual in reducing out-of-home placements. Although the parents believed that MST brought about a rapid and effective change, this was not reflected in objective indicators of antisocial behavior. These results are contrary to previous studies in the United States. The substantial improvements observed in both groups reflected the effectiveness of routinely offered interventions for this group of young people, at least when observed in clinical trials.3

Continue to: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy...

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

There is empirical support for using psychotherapy to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although medication management plays a leading role in treating ADHD, Janssen et al4 conducted a multicenter, single-blind trial comparing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) vs treatment as usual (TAU) for ADHD.

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of MBCT plus TAU vs TAU only in decreasing symptoms of adults with ADHD.4

Study design

- This multicenter, single-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted in the Netherlands. Participants (N = 120) met criteria for ADHD and were age ≥18. Patients were randomly assigned to MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU only (n = 60). Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group received weekly group therapy sessions, meditation exercises, psychoeducation, and group discussions. Patients in the TAU-only group received pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation.4

- Blinded clinicians used the Connors’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale to assess ADHD symptoms.4

- Secondary outcomes were determined by self-reported questionnaires that patients completed online.4

- All statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat sample as well as the per protocol sample.4

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was ADHD symptoms rated by clinicians. Secondary outcomes included self-reported ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, mindfulness skills, positive mental health, and general functioning. Outcomes were examined at baseline and then at post treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-up.4

- Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had a significant decrease in clinician-rated ADHD symptoms that was maintained at 6-month follow-up. More patients in the MBCT plus TAU group (27%) vs patients in the TAU group (4%) showed a ≥30% reduction in ADHD symptoms. Compared with patients in the TAU group, patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had significant improvements in ADHD symptoms, mindfulness skills, and positive mental health at post treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Compared with those receiving TAU only, patients treated with MBCT plus TAU reported no improvement in executive functioning at post treatment, but did improve at 6-month follow-up.4

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with TAU only, MBCT plus TAU is more effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, with a lasting effect at 6-month follow-up. In terms of secondary outcomes, MBCT plus TAU proved to be effective in improving mindfulness, self-compassion, positive mental health, and executive functioning. The results of this trial demonstrate that psychosocial treatments can be effective in addition to TAU in patients with ADHD, and MBCT holds promise for adult ADHD.4

1. Pompoli A, Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(12):1945-1953.

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder . https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed September 8, 2019.

Psychotherapy is among the evidence-based treatment options for treating various psychiatric disorders. How we approach psychiatric disorders via psychotherapy has been shaped by numerous theories of personality and psychopathology, including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, systems, and existential-humanistic approaches. Whether used as primary treatment or in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy has played a pivotal role in shaping psychiatric disease management and treatment. Several evidence-based therapy modalities have been used throughout the years and continue to significantly improve and impact our patients’ lives. In the armamentarium of treatment modalities, therapy takes the leading role for several conditions. Here we review 4 studies from current psychotherapy literature; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-4

1.

Panic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 3.7% in the general population. Three treatment modalities recommended for patients with panic disorder are psychological therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and self-help. Among the psychological therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used.1

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder has been proven to be an efficacious and impactful treatment. For panic disorder, CBT may consist of different combinations of several therapeutic components, such as relaxation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and/or in vivo exposure. It is therefore important, both theoretically and clinically, to examine whether specific components of CBT or their combinations are superior to others for treating panic disorder.1

Pompoli et al1 conducted a component network meta-analysis (NMA) of 72 studies in order to determine which CBT components were the most efficacious in treating patients with panic disorder. Component NMA is an extension of standard NMA; it is used to disentangle the treatment effects of different components included in composite interventions.1

The aim of this study was to determine which specific component or combination of components was superior to others when treating panic disorder.1

Study design

- Researchers reviewed 2,526 references from Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central and selected 72 studies that included 4,064 patients with panic disorder.1

- The primary outcome was remission of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the short term (3 to 6 months). Remission was defined as achieving a score of ≤7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).1

- Secondary outcomes included response (≥40% reduction in PDSS score from baseline) and dropout for any reason in the short term.1

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Using component NMA, researchers determined that interoceptive exposure and face-to-face setting (administration of therapeutic components in a face-to-face setting rather than through self-help means) led to better efficacy and acceptability. Muscle relaxation and virtual reality exposure corresponded to lower efficacy. Breathing retraining and in vivo exposure improved treatment acceptability, but had small effects on efficacy.1

- Based on an analysis of remission rates, the most efficacious CBT incorporated cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure. The least efficacious CBT incorporated breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, in vivo exposure, and virtual reality exposure.1

- Application of cognitive and behavioral therapeutic elements was superior to administration of behavioral elements alone. When administering CBT, face-to-face therapy led to better outcomes in response and remission rates. Dropout rates occurred at a lower frequency when CBT was administered face-to-face when compared with self-help groups. The placebo effect was associated with the highest dropout rate.1

Conclusion

- Findings from this meta-analysis have high practical utility. Which CBT components are used can significantly alter CBT’s efficacy and acceptability in patients with panic disorder.1

- The “most efficacious CBT” would include cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure delivered in a face-to-face setting. Breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, and virtual reality may have a minimal or even negative impact.1

- Limitations of this meta-analysis include the high number of studies used for the data analysis, complex statistical analysis, inability to include unpublished studies, and limited relevant studies. A future implication of this study is the consideration of formal methodology based on the clinical application of efficacious CBT components when treating patients with panic disorder.1

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

Psychotherapy is also a useful modality for treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Sloan et al2 compared brief exposure-based treatment with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for PTSD.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of PTSD and acute stress disorder recommend the use of individual, trauma-focused therapies that focus on exposure and cognitive restructuring, such as prolonged exposure, CPT, and written narrative exposure.5

Continue to: One type of written narrative...

One type of written narrative exposure treatment is written exposure therapy (WET), which consists of 5 sessions during which patients write about their trauma. The first session is comprised of psychoeducation about PTSD and a review of treatment reasoning, followed by 30 minutes of writing. The therapist provides feedback and instructions. Written exposure therapy requires less therapist training and less supervision than prolonged exposure or CPT. Prior studies have suggested that WET can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in various trauma survivors.2

Although efficacious for PTSD, WET had not been compared with CPT, which is the most commonly used first-line treatment of PTSD. The aim of this study was to determine whether WET is noninferior to CPT.2

Study design

- In this randomized noninferiority clinical trial conducted in Boston, Massachusetts from February 28, 2013 to November 6, 2016, 126 veterans and non-veteran adults were randomized to WET or CPT. Participants met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD and were taking stable doses of their medications for at least 4 weeks.2

- Participants assigned to CPT (n = 63) underwent 12 sessions, and participants assigned to WET (n = 63) received 5 sessions. Cognitive processing therapy was conducted over 60-minute weekly sessions. Written exposure therapy consisted of an initial session that was 60 minutes long and four 40-minute follow-up sessions.2

- Interviews were conducted by 4 independent evaluators at baseline and 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks. During the WET sessions, participants wrote about a traumatic event while focusing on details, thoughts, and feelings associated with the event.2

- Cognitive processing therapy involved 12 trauma-focused therapy sessions during which participants learn how to become aware of and address problematic cognitions about the trauma as well as thoughts about themselves and others. Between sessions, participants were required to write 2 trauma accounts and complete other assignments.2

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was change in total score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). The CAPS-5 scores for participants in the WET group were noninferior to those for participants in the CPT group at all assessment points.2

- Participants did not significantly differ in age, education, income, or PTSD severity. Participants in the 2 groups did not differ in treatment expectations or level of satisfaction with treatment. Individuals assigned to CPT were more likely to drop out of the study: 20 participants in the CPT group dropped out in the first 5 sessions, whereas only 4 dropped out of the WET group. The dropout rate in the CPT group was 39.7%. Improvements in PTSD symptoms in the WET group were noninferior to improvements in the CPT group.2

- Written exposure therapy showed no difference compared with CPT in decreasing PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that PTSD symptoms can decrease with a smaller number of shorter therapeutic sessions.2

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated noninferiority between an established, commonly used PTSD therapy (CPT) and a version of exposure therapy that is briefer, simpler, and requires less homework and less therapist training and expertise. This “lower-dose” approach may improve access for the expanding number of patients who require treatment for PTSD, especially in the Veterans Affairs system.2

- In summary, WET is well tolerated and time-efficient. Although it requires fewer sessions, WET was noninferior to CPT.2

Continue to: Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual...

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive, family-based, home-based intervention for young people with serious antisocial behavior. It has been found effective for childhood conduct disorders in the United States. However, previous studies that supported its efficacy were conducted by the therapy’s developers and used noncomprehensive comparators, such as individual therapy. Fonagy et al3 assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MST vs management as usual for treating adolescent antisocial behavior. This is the first study that was performed by independent investigators and used a comprehensive control.3

Study design

- This 18-month, multisite, pragmatic, randomized controlled superiority trial was conducted in England.3

- Participants were age 11 to 17, with moderate to severe antisocial behavior. They had at least 3 severity criteria indicating difficulties across several settings and at least one of the 5 inclusion criteria for antisocial behavior. Six hundred eighty-four families were randomly assigned to MST or management as usual, and 491 families completed the study.3

- For the MST intervention, therapists worked with the adolescent’s caregiver 3 times a week for 3 to 5 months to improve parenting skills, enhance family relationships, increase support from social networks, develop skills and resources, address communication problems, increase school attendance and achievement, and reduce the adolescent’s association with delinquent peers.3

- For the management as usual intervention, management was based on local services for young people and was designed to be in line with current community practice.3

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in out-of-home placements at 18 months. The secondary outcomes were time to first criminal offense and the total number of offenses.3

- In terms of the risk of out-of-home placement, MST had no effect: 13% of participants in the MST group had out-of-home placement at 18 months, compared with 11% in the management-as-usual group.3

- Multisystemic therapy also did not significantly delay the time to first offense (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.33). Also, at 18-month follow-up, participants in the MST group had committed more offenses than those in the management-as-usual group, although the difference was not statistically significant.3

- Parents in the MST group reported increased parental support and involvement and reduced problems at 6 months, but the adolescents’ reports of parenting behavior indicated no significant effect for MST vs management as usual at any time point.3

Conclusion

- Multisystemic therapy was not superior to management as usual in reducing out-of-home placements. Although the parents believed that MST brought about a rapid and effective change, this was not reflected in objective indicators of antisocial behavior. These results are contrary to previous studies in the United States. The substantial improvements observed in both groups reflected the effectiveness of routinely offered interventions for this group of young people, at least when observed in clinical trials.3

Continue to: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy...

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

There is empirical support for using psychotherapy to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although medication management plays a leading role in treating ADHD, Janssen et al4 conducted a multicenter, single-blind trial comparing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) vs treatment as usual (TAU) for ADHD.

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of MBCT plus TAU vs TAU only in decreasing symptoms of adults with ADHD.4

Study design

- This multicenter, single-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted in the Netherlands. Participants (N = 120) met criteria for ADHD and were age ≥18. Patients were randomly assigned to MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU only (n = 60). Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group received weekly group therapy sessions, meditation exercises, psychoeducation, and group discussions. Patients in the TAU-only group received pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation.4

- Blinded clinicians used the Connors’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale to assess ADHD symptoms.4

- Secondary outcomes were determined by self-reported questionnaires that patients completed online.4

- All statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat sample as well as the per protocol sample.4

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was ADHD symptoms rated by clinicians. Secondary outcomes included self-reported ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, mindfulness skills, positive mental health, and general functioning. Outcomes were examined at baseline and then at post treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-up.4

- Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had a significant decrease in clinician-rated ADHD symptoms that was maintained at 6-month follow-up. More patients in the MBCT plus TAU group (27%) vs patients in the TAU group (4%) showed a ≥30% reduction in ADHD symptoms. Compared with patients in the TAU group, patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had significant improvements in ADHD symptoms, mindfulness skills, and positive mental health at post treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Compared with those receiving TAU only, patients treated with MBCT plus TAU reported no improvement in executive functioning at post treatment, but did improve at 6-month follow-up.4

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with TAU only, MBCT plus TAU is more effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, with a lasting effect at 6-month follow-up. In terms of secondary outcomes, MBCT plus TAU proved to be effective in improving mindfulness, self-compassion, positive mental health, and executive functioning. The results of this trial demonstrate that psychosocial treatments can be effective in addition to TAU in patients with ADHD, and MBCT holds promise for adult ADHD.4

Psychotherapy is among the evidence-based treatment options for treating various psychiatric disorders. How we approach psychiatric disorders via psychotherapy has been shaped by numerous theories of personality and psychopathology, including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, systems, and existential-humanistic approaches. Whether used as primary treatment or in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy has played a pivotal role in shaping psychiatric disease management and treatment. Several evidence-based therapy modalities have been used throughout the years and continue to significantly improve and impact our patients’ lives. In the armamentarium of treatment modalities, therapy takes the leading role for several conditions. Here we review 4 studies from current psychotherapy literature; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-4

1.

Panic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 3.7% in the general population. Three treatment modalities recommended for patients with panic disorder are psychological therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and self-help. Among the psychological therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used.1

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder has been proven to be an efficacious and impactful treatment. For panic disorder, CBT may consist of different combinations of several therapeutic components, such as relaxation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and/or in vivo exposure. It is therefore important, both theoretically and clinically, to examine whether specific components of CBT or their combinations are superior to others for treating panic disorder.1

Pompoli et al1 conducted a component network meta-analysis (NMA) of 72 studies in order to determine which CBT components were the most efficacious in treating patients with panic disorder. Component NMA is an extension of standard NMA; it is used to disentangle the treatment effects of different components included in composite interventions.1

The aim of this study was to determine which specific component or combination of components was superior to others when treating panic disorder.1

Study design

- Researchers reviewed 2,526 references from Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central and selected 72 studies that included 4,064 patients with panic disorder.1

- The primary outcome was remission of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the short term (3 to 6 months). Remission was defined as achieving a score of ≤7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).1

- Secondary outcomes included response (≥40% reduction in PDSS score from baseline) and dropout for any reason in the short term.1

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Using component NMA, researchers determined that interoceptive exposure and face-to-face setting (administration of therapeutic components in a face-to-face setting rather than through self-help means) led to better efficacy and acceptability. Muscle relaxation and virtual reality exposure corresponded to lower efficacy. Breathing retraining and in vivo exposure improved treatment acceptability, but had small effects on efficacy.1

- Based on an analysis of remission rates, the most efficacious CBT incorporated cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure. The least efficacious CBT incorporated breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, in vivo exposure, and virtual reality exposure.1

- Application of cognitive and behavioral therapeutic elements was superior to administration of behavioral elements alone. When administering CBT, face-to-face therapy led to better outcomes in response and remission rates. Dropout rates occurred at a lower frequency when CBT was administered face-to-face when compared with self-help groups. The placebo effect was associated with the highest dropout rate.1

Conclusion

- Findings from this meta-analysis have high practical utility. Which CBT components are used can significantly alter CBT’s efficacy and acceptability in patients with panic disorder.1

- The “most efficacious CBT” would include cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure delivered in a face-to-face setting. Breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, and virtual reality may have a minimal or even negative impact.1

- Limitations of this meta-analysis include the high number of studies used for the data analysis, complex statistical analysis, inability to include unpublished studies, and limited relevant studies. A future implication of this study is the consideration of formal methodology based on the clinical application of efficacious CBT components when treating patients with panic disorder.1

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

Psychotherapy is also a useful modality for treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Sloan et al2 compared brief exposure-based treatment with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for PTSD.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of PTSD and acute stress disorder recommend the use of individual, trauma-focused therapies that focus on exposure and cognitive restructuring, such as prolonged exposure, CPT, and written narrative exposure.5

Continue to: One type of written narrative...

One type of written narrative exposure treatment is written exposure therapy (WET), which consists of 5 sessions during which patients write about their trauma. The first session is comprised of psychoeducation about PTSD and a review of treatment reasoning, followed by 30 minutes of writing. The therapist provides feedback and instructions. Written exposure therapy requires less therapist training and less supervision than prolonged exposure or CPT. Prior studies have suggested that WET can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in various trauma survivors.2

Although efficacious for PTSD, WET had not been compared with CPT, which is the most commonly used first-line treatment of PTSD. The aim of this study was to determine whether WET is noninferior to CPT.2

Study design

- In this randomized noninferiority clinical trial conducted in Boston, Massachusetts from February 28, 2013 to November 6, 2016, 126 veterans and non-veteran adults were randomized to WET or CPT. Participants met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD and were taking stable doses of their medications for at least 4 weeks.2

- Participants assigned to CPT (n = 63) underwent 12 sessions, and participants assigned to WET (n = 63) received 5 sessions. Cognitive processing therapy was conducted over 60-minute weekly sessions. Written exposure therapy consisted of an initial session that was 60 minutes long and four 40-minute follow-up sessions.2

- Interviews were conducted by 4 independent evaluators at baseline and 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks. During the WET sessions, participants wrote about a traumatic event while focusing on details, thoughts, and feelings associated with the event.2

- Cognitive processing therapy involved 12 trauma-focused therapy sessions during which participants learn how to become aware of and address problematic cognitions about the trauma as well as thoughts about themselves and others. Between sessions, participants were required to write 2 trauma accounts and complete other assignments.2

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was change in total score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). The CAPS-5 scores for participants in the WET group were noninferior to those for participants in the CPT group at all assessment points.2

- Participants did not significantly differ in age, education, income, or PTSD severity. Participants in the 2 groups did not differ in treatment expectations or level of satisfaction with treatment. Individuals assigned to CPT were more likely to drop out of the study: 20 participants in the CPT group dropped out in the first 5 sessions, whereas only 4 dropped out of the WET group. The dropout rate in the CPT group was 39.7%. Improvements in PTSD symptoms in the WET group were noninferior to improvements in the CPT group.2

- Written exposure therapy showed no difference compared with CPT in decreasing PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that PTSD symptoms can decrease with a smaller number of shorter therapeutic sessions.2

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated noninferiority between an established, commonly used PTSD therapy (CPT) and a version of exposure therapy that is briefer, simpler, and requires less homework and less therapist training and expertise. This “lower-dose” approach may improve access for the expanding number of patients who require treatment for PTSD, especially in the Veterans Affairs system.2

- In summary, WET is well tolerated and time-efficient. Although it requires fewer sessions, WET was noninferior to CPT.2

Continue to: Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual...

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive, family-based, home-based intervention for young people with serious antisocial behavior. It has been found effective for childhood conduct disorders in the United States. However, previous studies that supported its efficacy were conducted by the therapy’s developers and used noncomprehensive comparators, such as individual therapy. Fonagy et al3 assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MST vs management as usual for treating adolescent antisocial behavior. This is the first study that was performed by independent investigators and used a comprehensive control.3

Study design

- This 18-month, multisite, pragmatic, randomized controlled superiority trial was conducted in England.3

- Participants were age 11 to 17, with moderate to severe antisocial behavior. They had at least 3 severity criteria indicating difficulties across several settings and at least one of the 5 inclusion criteria for antisocial behavior. Six hundred eighty-four families were randomly assigned to MST or management as usual, and 491 families completed the study.3

- For the MST intervention, therapists worked with the adolescent’s caregiver 3 times a week for 3 to 5 months to improve parenting skills, enhance family relationships, increase support from social networks, develop skills and resources, address communication problems, increase school attendance and achievement, and reduce the adolescent’s association with delinquent peers.3

- For the management as usual intervention, management was based on local services for young people and was designed to be in line with current community practice.3

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in out-of-home placements at 18 months. The secondary outcomes were time to first criminal offense and the total number of offenses.3

- In terms of the risk of out-of-home placement, MST had no effect: 13% of participants in the MST group had out-of-home placement at 18 months, compared with 11% in the management-as-usual group.3

- Multisystemic therapy also did not significantly delay the time to first offense (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.33). Also, at 18-month follow-up, participants in the MST group had committed more offenses than those in the management-as-usual group, although the difference was not statistically significant.3

- Parents in the MST group reported increased parental support and involvement and reduced problems at 6 months, but the adolescents’ reports of parenting behavior indicated no significant effect for MST vs management as usual at any time point.3

Conclusion

- Multisystemic therapy was not superior to management as usual in reducing out-of-home placements. Although the parents believed that MST brought about a rapid and effective change, this was not reflected in objective indicators of antisocial behavior. These results are contrary to previous studies in the United States. The substantial improvements observed in both groups reflected the effectiveness of routinely offered interventions for this group of young people, at least when observed in clinical trials.3

Continue to: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy...

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

There is empirical support for using psychotherapy to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although medication management plays a leading role in treating ADHD, Janssen et al4 conducted a multicenter, single-blind trial comparing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) vs treatment as usual (TAU) for ADHD.

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of MBCT plus TAU vs TAU only in decreasing symptoms of adults with ADHD.4

Study design

- This multicenter, single-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted in the Netherlands. Participants (N = 120) met criteria for ADHD and were age ≥18. Patients were randomly assigned to MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU only (n = 60). Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group received weekly group therapy sessions, meditation exercises, psychoeducation, and group discussions. Patients in the TAU-only group received pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation.4

- Blinded clinicians used the Connors’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale to assess ADHD symptoms.4

- Secondary outcomes were determined by self-reported questionnaires that patients completed online.4

- All statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat sample as well as the per protocol sample.4

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was ADHD symptoms rated by clinicians. Secondary outcomes included self-reported ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, mindfulness skills, positive mental health, and general functioning. Outcomes were examined at baseline and then at post treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-up.4

- Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had a significant decrease in clinician-rated ADHD symptoms that was maintained at 6-month follow-up. More patients in the MBCT plus TAU group (27%) vs patients in the TAU group (4%) showed a ≥30% reduction in ADHD symptoms. Compared with patients in the TAU group, patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had significant improvements in ADHD symptoms, mindfulness skills, and positive mental health at post treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Compared with those receiving TAU only, patients treated with MBCT plus TAU reported no improvement in executive functioning at post treatment, but did improve at 6-month follow-up.4

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with TAU only, MBCT plus TAU is more effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, with a lasting effect at 6-month follow-up. In terms of secondary outcomes, MBCT plus TAU proved to be effective in improving mindfulness, self-compassion, positive mental health, and executive functioning. The results of this trial demonstrate that psychosocial treatments can be effective in addition to TAU in patients with ADHD, and MBCT holds promise for adult ADHD.4

1. Pompoli A, Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(12):1945-1953.

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder . https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed September 8, 2019.

1. Pompoli A, Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(12):1945-1953.

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder . https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed September 8, 2019.

Gut microbiota and its implications for psychiatry: A review of 3 studies

The “human microbiota” describes all microorganisms within the human body, including bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotes. The related term “microbiome” refers to the complete catalog of these microbes and their genes.1 There is a growing awareness that the human microbiota plays an important role in maintaining mental health, and that a disruption in its composition can contribute to manifestations of psychiatric disorders. A growing body of evidence has also linked mental health outcomes to the gut microbiome, suggesting that the gut microbiota can modulate the gut-brain axis.2

Numerous neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and acetylcholine, are produced in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and our diet is vital in sustaining and replenishing them. At the same time, our brain regulates our GI tract by secretion of hormones such as oxytocin, leptin, ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, corticotrophin-releasing factor, and a plethora of others. Dysregulation of this microbiome can lead to both physical and mental illnesses. Symptoms of psychiatric disorders, such as depression, psychosis, anxiety, and autism, can be a consequence of this dysregulation.2

Our diet can also modify the gut microorganisms and therefore many of its metabolic pathways. More attention has been given to pre- and probiotics and their effects on DNA by epigenetic changes. One can quickly start to appreciate how this intricate crosstalk can lead to a variety of pathologic and psychiatric problems that have an adverse effect on autoimmune, inflammatory, metabolic, cognitive, and behavioral processes.2,3

Thus far, links have mostly been reported in animal models, and human studies are limited.4 Researchers are just beginning to elucidate how the microbiota affect gut-brain signaling in humans. Such mechanisms may include alterations in microbial composition, immune activation, vagus nerve signaling, alterations in tryptophan metabolism, production of specific microbial neuroactive metabolites, and bacterial cell wall sugars.5 The microbiota-gut-brain axis plays a part in regulating/programming the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis throughout the life span.3 The interactions between the gut microbiome, the immune system, and the CNS are regulated through pathways that involve endocrine functions (HPA axis), the immune system, and metabolic factors.3,4 Recent research focusing on the gut microbiome has also given rise to international projects such as the Human Microbiome Project (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012).3

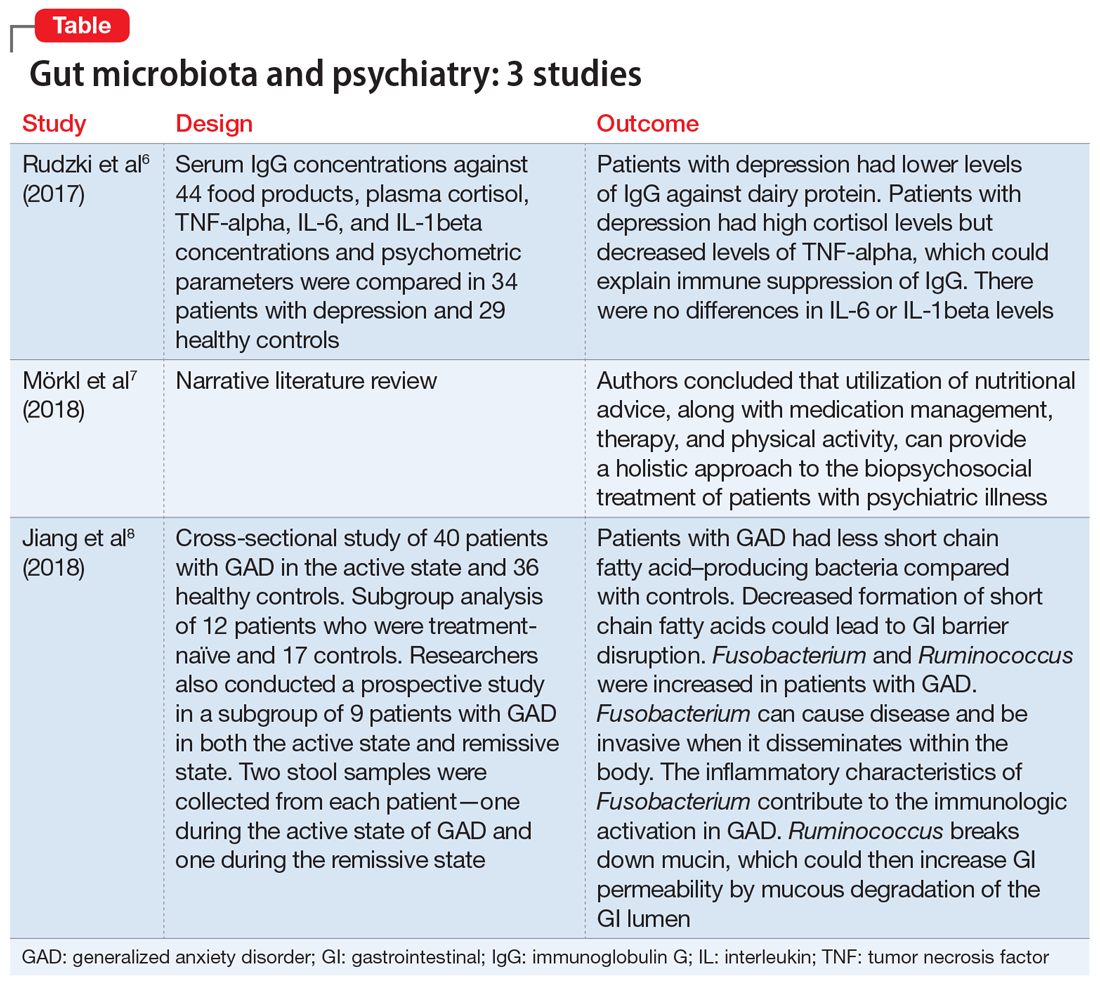

Several studies have looked into psychiatry and inflammatory/immune pathways. Here we review 3 recent studies that have focused on the gut-brain axis (Table6-8).

1. Rudzki L, Pawlak D, Pawlak K, et al. Immune suppression of IgG response against dairy proteins in major depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):268.

The aim of this study was to evaluate immunoglobulin G (IgG) response against 40 food products in patients with depression vs those in a control group, along with changes in inflammatory markers, psychological stress, and dietary variables.6

Study design

- N = 63, IgG levels against 44 food products, cortisol levels, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-1 beta levels were recorded. The psychological parameters of 34 participants with depression and 29 controls were compared using the Hamilton Depression Rating scale, (HAM-D-17), Perceived Stress scale, and Symptom Checklist scale. The study was conducted in Poland.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Patients who were depressed had lower IgG levels against dairy products compared to controls when there was high dairy consumption. However, there was no overall difference between patients and controls in mean IgG concentration against food products.

- Patients who were depressed had higher levels of cortisol. Levels of cortisol had a positive correlation with HAM-D-17 score. Patients with depression had lower levels of TNF-alpha.

Conclusion

- Patients with depression had lower levels of IgG against dairy protein. Patients with depression had high cortisol levels but decreased levels of TNF-alpha, which could explain an immune suppression of IgG in these patients. There were no differences in IL-6 or IL-1beta levels.

Hypercortisolemia is present in approximately 60% of patients with depression. Elevated cortisol levels have a negative effect on lymphocyte function. B-lymphocytes (CD 10+ and CD 19+) are sensitive to glucocorticoids. Studies in mice have demonstrated that elevated glucocorticoid levels are associated with a 50% decrease in serum B-lymphocytes, and this can be explained by downregulation of c-myc protein, which plays a role in cell proliferation and cell survival. Glucocorticoids also decrease levels of protein kinases that are vital for the cell cycle to continue, and they upregulate p27 and p21, which are cell cycle inhibitors. Therefore, if high cortisol suppresses B-lymphocyte production, this can explain how patients with depression have low IgG levels, since B-lymphocytes differentiate into plasma cells that will produce antibodies.6

Depression can trigger an inflammatory response by increasing levels of inflammatory cytokines, acute phase reactants, and oxidative molecules. The inflammatory response can lead to intestinal wall disruption, and therefore bacteria can migrate across the GI barrier, along with food antigens, which could then lead to food antigen hypersensitivity.6

The significance of diet

Many studies have looked into specific types of diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, the ketogenic diet, and the addition of supplements such as probiotics, omega-3 fatty acids, zinc, and multivitamins.7 The Mediterranean diet is high in fiber, nuts, legumes, and fish.7 The ketogenic diet includes a controlled amount of fat, but is low in protein and carbohydrates.7 The main point is that a balanced diet can have a positive effect on mental health.7 The Mediterranean diet has shown to decrease the incidence of cardiovascular disease and lower the risk of depression.7 In animal studies, the ketogenic diet has improved anxiety, depression, and autism.7 Diet clearly affects gut microbiota and, as a consequence, the body’s level of inflammation.7

Continue to: The following review...

The following review highlighted the significance of diet on gut microbiome and mental health.7

2. Mörkl S, Wagner-Skacel J, Lahousen T, et al. The role of nutrition and the gut- brain axis in psychiatry: a review of the literature. Neuropsychobiology. 2018;17: 1-9.

Study design

- These researchers provided a narrative review of the significance of a healthy diet and nutritional supplements on the gut microbiome and the treatment of patients with psychiatric illness.

Outcomes

- This review suggested dietary coaching as a nonpharmacologic treatment for patients with psychiatric illness.

Conclusion

- The utilization of nutritional advice, along with medication management, therapy, and physical activity, can provide a holistic approach to the biopsychosocial treatment of patients with psychiatric illness.

This review also emphasized the poor dietary trends of Westernized countries, which include calorie-dense, genetically altered, processed meals. As Mörkl et al7 noted, we are overfed but undernourished. Mörkl et al7 reviewed studies that involve dietary coaching as part of the treatment plan of patients with mental illness. In one of these studies, patients who received nutritional advice and coaching over 6 weeks had a 40% to 50% decrease in depressive symptoms. These effects persisted for 2 more years. Mörkl et al7 also reviewed an Italian study that found that providing nutritional advice in patients with affective disorders and psychosis helped improve symptom severity and sleep.7

Continue to: Mörkl et al...

Mörkl et al7 also reviewed dietary supplements. Some studies have linked use of omega-3 fatty acids with improvement in affective disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, and posttraumatic stress disorder, as well as cardiovascular conditions. Omega-3 fatty acids may exert beneficial effects by enhancing brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurogenesis as well as by decreasing inflammation.7

Zinc supplementation can also improve depression, as it has been linked to cytokine variation and hippocampal neuronal growth. Vitamin B9 deficiency and vitamin D deficiency also have been associated with depression. Mörkl et al7 emphasized that a balanced diet that incorporates a variety of nutrients is more beneficial than supplementation of any individual vitamin alone.

Researchers have long emphasized the importance of a healthy balanced diet when treating patients with medical conditions such as cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases. Based on the studies Mörkl et al7 reviewed, the same emphasis should be communicated to our patients who suffer from psychiatric conditions.

The gut and anxiety

The gut microbiome has also been an area of research when studying generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).8

3. Jiang HY, Zhang X, Yu ZH, et al. Altered gut microbiota profile in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;104:130-136.

The aim of the study was to determine if there were changes in the composition of the gut microbiome in patients with GAD compared with healthy controls.8

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- A cross-sectional study of 76 patients in Zhejiang, China. Forty patients with GAD in the active state and 36 healthy controls were compared in terms of composition of GI microbacterial flora.

- Researchers also examined a subgroup of 12 patients who were treatment-naïve and 17 controls. Stool samples were collected from the 12 patients who were treatment-naïve before initiating medication.

- Researchers also conducted a prospective study in a subgroup of 9 patients with GAD in both the active state and remissive state. Two stool samples were collected from each patient—one during the active state of GAD and one during the remissive state—for a total of 18 samples. Stool samples analyzed with the use of polymerase chain reaction and microbial analysis.

- Patients completed the Hamilton Anxiety Rating (HAM-A) scale and were classified into groups. Those with HAM-A scores >14 were classified as being in the active state of GAD, and those with scores <7 were classified as being in the remissive state.

Outcomes

- Among the samples collected, 8 bacterial taxa were found in different amounts in patients with GAD and healthy controls. Bacteroidetes, Ruminococcus gnavus, and Fusobacterium were increased in patients with GAD compared with controls, while Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium rectale, Sutterella, Lachnospira, and Butyricicoccus were increased in healthy controls.

- Bacterial variety was notably lower in the 12 patients who were treatment-naïve compared with the control group.

- There was no notable difference in microbial composition between patients in the active vs remissive state.

Conclusion

- Patients with GAD had less short chain fatty acid–producing bacteria (Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium rectale, Sutterella, Lachnospira, and Butyricicoccus) compared with controls. Decreased formation of short chain fatty acids could lead to GI barrier disruption. Fusobacterium and Ruminococcus were increased in patients with GAD. Fusobacterium can cause disease and be invasive when it disseminates within the body. The inflammatory characteristics of Fusobacterium contribute to the immunologic activation in GAD. Ruminococcus breaks down mucin, which could then increase GI permeability by mucous degradation of the GI lumen.

Changes in food processing and manufacturing have led to changes in our diets. Changes in our normal GI microbacterial flora could lead to increased gut permeability, bacterial dissemination, and subsequent systemic inflammation. Research has shown that the composition of the microbiota changes across the life span.9 A balanced intake of nutrients is important for both our physical and mental health and safeguards the basis of gut microbiome regulation. A well-regulated gut microbiome ensures low levels of inflammation in the brain and body. Lifestyle modifications and dietary coaching could be practical interventions for patients with psychiatric conditions.5 Current advances in technology now offer precise analyses of thousands of metabolites, enabling metabolomics to offer the promise of discovering new drug targets and biomarkers that may help pave a way to precision medicine.

1. Dave M, Higgins PD, Middha S, et al. The human gut microbiome: current knowledge, challenges, and future directions. Transl Res. 2012;160:246-257.

2. Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

3. Malan-Muller S, Valles-Colomer M, Raes J, et al. The gut microbiome and mental health: implications for anxiety-and trauma-related disorders. OMICS. 2018;22(2):90-107.

4. Du Toit A. The gut microbiome and mental health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(4):196.

5. Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(10):701-712.

6. Rudzki L, Pawlak D, Pawlak K, et al. Immune suppression of IgG response against dairy proteins in major depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):268.

7. Mörkl S, Wagner-Skacel J, Lahousen T, et al. The role of nutrition and the gut-brain axis in psychiatry: a review of the literature. Neuropsychobiology. 2018;17:1-9.

8. Jiang HY, Zhang X, Yu ZH, et al. Altered gut microbiota profile in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;104:130-136.

9. Douglas-Escobar M, Elliott E, Neu J. Effect of intestinal microbial ecology on the developing brain. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(4):374-379.

The “human microbiota” describes all microorganisms within the human body, including bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotes. The related term “microbiome” refers to the complete catalog of these microbes and their genes.1 There is a growing awareness that the human microbiota plays an important role in maintaining mental health, and that a disruption in its composition can contribute to manifestations of psychiatric disorders. A growing body of evidence has also linked mental health outcomes to the gut microbiome, suggesting that the gut microbiota can modulate the gut-brain axis.2

Numerous neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and acetylcholine, are produced in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and our diet is vital in sustaining and replenishing them. At the same time, our brain regulates our GI tract by secretion of hormones such as oxytocin, leptin, ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, corticotrophin-releasing factor, and a plethora of others. Dysregulation of this microbiome can lead to both physical and mental illnesses. Symptoms of psychiatric disorders, such as depression, psychosis, anxiety, and autism, can be a consequence of this dysregulation.2

Our diet can also modify the gut microorganisms and therefore many of its metabolic pathways. More attention has been given to pre- and probiotics and their effects on DNA by epigenetic changes. One can quickly start to appreciate how this intricate crosstalk can lead to a variety of pathologic and psychiatric problems that have an adverse effect on autoimmune, inflammatory, metabolic, cognitive, and behavioral processes.2,3

Thus far, links have mostly been reported in animal models, and human studies are limited.4 Researchers are just beginning to elucidate how the microbiota affect gut-brain signaling in humans. Such mechanisms may include alterations in microbial composition, immune activation, vagus nerve signaling, alterations in tryptophan metabolism, production of specific microbial neuroactive metabolites, and bacterial cell wall sugars.5 The microbiota-gut-brain axis plays a part in regulating/programming the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis throughout the life span.3 The interactions between the gut microbiome, the immune system, and the CNS are regulated through pathways that involve endocrine functions (HPA axis), the immune system, and metabolic factors.3,4 Recent research focusing on the gut microbiome has also given rise to international projects such as the Human Microbiome Project (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012).3

Several studies have looked into psychiatry and inflammatory/immune pathways. Here we review 3 recent studies that have focused on the gut-brain axis (Table6-8).

1. Rudzki L, Pawlak D, Pawlak K, et al. Immune suppression of IgG response against dairy proteins in major depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):268.

The aim of this study was to evaluate immunoglobulin G (IgG) response against 40 food products in patients with depression vs those in a control group, along with changes in inflammatory markers, psychological stress, and dietary variables.6

Study design

- N = 63, IgG levels against 44 food products, cortisol levels, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-1 beta levels were recorded. The psychological parameters of 34 participants with depression and 29 controls were compared using the Hamilton Depression Rating scale, (HAM-D-17), Perceived Stress scale, and Symptom Checklist scale. The study was conducted in Poland.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Patients who were depressed had lower IgG levels against dairy products compared to controls when there was high dairy consumption. However, there was no overall difference between patients and controls in mean IgG concentration against food products.

- Patients who were depressed had higher levels of cortisol. Levels of cortisol had a positive correlation with HAM-D-17 score. Patients with depression had lower levels of TNF-alpha.

Conclusion

- Patients with depression had lower levels of IgG against dairy protein. Patients with depression had high cortisol levels but decreased levels of TNF-alpha, which could explain an immune suppression of IgG in these patients. There were no differences in IL-6 or IL-1beta levels.

Hypercortisolemia is present in approximately 60% of patients with depression. Elevated cortisol levels have a negative effect on lymphocyte function. B-lymphocytes (CD 10+ and CD 19+) are sensitive to glucocorticoids. Studies in mice have demonstrated that elevated glucocorticoid levels are associated with a 50% decrease in serum B-lymphocytes, and this can be explained by downregulation of c-myc protein, which plays a role in cell proliferation and cell survival. Glucocorticoids also decrease levels of protein kinases that are vital for the cell cycle to continue, and they upregulate p27 and p21, which are cell cycle inhibitors. Therefore, if high cortisol suppresses B-lymphocyte production, this can explain how patients with depression have low IgG levels, since B-lymphocytes differentiate into plasma cells that will produce antibodies.6

Depression can trigger an inflammatory response by increasing levels of inflammatory cytokines, acute phase reactants, and oxidative molecules. The inflammatory response can lead to intestinal wall disruption, and therefore bacteria can migrate across the GI barrier, along with food antigens, which could then lead to food antigen hypersensitivity.6

The significance of diet

Many studies have looked into specific types of diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, the ketogenic diet, and the addition of supplements such as probiotics, omega-3 fatty acids, zinc, and multivitamins.7 The Mediterranean diet is high in fiber, nuts, legumes, and fish.7 The ketogenic diet includes a controlled amount of fat, but is low in protein and carbohydrates.7 The main point is that a balanced diet can have a positive effect on mental health.7 The Mediterranean diet has shown to decrease the incidence of cardiovascular disease and lower the risk of depression.7 In animal studies, the ketogenic diet has improved anxiety, depression, and autism.7 Diet clearly affects gut microbiota and, as a consequence, the body’s level of inflammation.7

Continue to: The following review...

The following review highlighted the significance of diet on gut microbiome and mental health.7

2. Mörkl S, Wagner-Skacel J, Lahousen T, et al. The role of nutrition and the gut- brain axis in psychiatry: a review of the literature. Neuropsychobiology. 2018;17: 1-9.

Study design

- These researchers provided a narrative review of the significance of a healthy diet and nutritional supplements on the gut microbiome and the treatment of patients with psychiatric illness.

Outcomes

- This review suggested dietary coaching as a nonpharmacologic treatment for patients with psychiatric illness.

Conclusion

- The utilization of nutritional advice, along with medication management, therapy, and physical activity, can provide a holistic approach to the biopsychosocial treatment of patients with psychiatric illness.

This review also emphasized the poor dietary trends of Westernized countries, which include calorie-dense, genetically altered, processed meals. As Mörkl et al7 noted, we are overfed but undernourished. Mörkl et al7 reviewed studies that involve dietary coaching as part of the treatment plan of patients with mental illness. In one of these studies, patients who received nutritional advice and coaching over 6 weeks had a 40% to 50% decrease in depressive symptoms. These effects persisted for 2 more years. Mörkl et al7 also reviewed an Italian study that found that providing nutritional advice in patients with affective disorders and psychosis helped improve symptom severity and sleep.7

Continue to: Mörkl et al...

Mörkl et al7 also reviewed dietary supplements. Some studies have linked use of omega-3 fatty acids with improvement in affective disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, and posttraumatic stress disorder, as well as cardiovascular conditions. Omega-3 fatty acids may exert beneficial effects by enhancing brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurogenesis as well as by decreasing inflammation.7

Zinc supplementation can also improve depression, as it has been linked to cytokine variation and hippocampal neuronal growth. Vitamin B9 deficiency and vitamin D deficiency also have been associated with depression. Mörkl et al7 emphasized that a balanced diet that incorporates a variety of nutrients is more beneficial than supplementation of any individual vitamin alone.

Researchers have long emphasized the importance of a healthy balanced diet when treating patients with medical conditions such as cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases. Based on the studies Mörkl et al7 reviewed, the same emphasis should be communicated to our patients who suffer from psychiatric conditions.

The gut and anxiety

The gut microbiome has also been an area of research when studying generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).8

3. Jiang HY, Zhang X, Yu ZH, et al. Altered gut microbiota profile in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;104:130-136.

The aim of the study was to determine if there were changes in the composition of the gut microbiome in patients with GAD compared with healthy controls.8

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- A cross-sectional study of 76 patients in Zhejiang, China. Forty patients with GAD in the active state and 36 healthy controls were compared in terms of composition of GI microbacterial flora.

- Researchers also examined a subgroup of 12 patients who were treatment-naïve and 17 controls. Stool samples were collected from the 12 patients who were treatment-naïve before initiating medication.

- Researchers also conducted a prospective study in a subgroup of 9 patients with GAD in both the active state and remissive state. Two stool samples were collected from each patient—one during the active state of GAD and one during the remissive state—for a total of 18 samples. Stool samples analyzed with the use of polymerase chain reaction and microbial analysis.

- Patients completed the Hamilton Anxiety Rating (HAM-A) scale and were classified into groups. Those with HAM-A scores >14 were classified as being in the active state of GAD, and those with scores <7 were classified as being in the remissive state.

Outcomes

- Among the samples collected, 8 bacterial taxa were found in different amounts in patients with GAD and healthy controls. Bacteroidetes, Ruminococcus gnavus, and Fusobacterium were increased in patients with GAD compared with controls, while Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium rectale, Sutterella, Lachnospira, and Butyricicoccus were increased in healthy controls.

- Bacterial variety was notably lower in the 12 patients who were treatment-naïve compared with the control group.

- There was no notable difference in microbial composition between patients in the active vs remissive state.

Conclusion

- Patients with GAD had less short chain fatty acid–producing bacteria (Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium rectale, Sutterella, Lachnospira, and Butyricicoccus) compared with controls. Decreased formation of short chain fatty acids could lead to GI barrier disruption. Fusobacterium and Ruminococcus were increased in patients with GAD. Fusobacterium can cause disease and be invasive when it disseminates within the body. The inflammatory characteristics of Fusobacterium contribute to the immunologic activation in GAD. Ruminococcus breaks down mucin, which could then increase GI permeability by mucous degradation of the GI lumen.

Changes in food processing and manufacturing have led to changes in our diets. Changes in our normal GI microbacterial flora could lead to increased gut permeability, bacterial dissemination, and subsequent systemic inflammation. Research has shown that the composition of the microbiota changes across the life span.9 A balanced intake of nutrients is important for both our physical and mental health and safeguards the basis of gut microbiome regulation. A well-regulated gut microbiome ensures low levels of inflammation in the brain and body. Lifestyle modifications and dietary coaching could be practical interventions for patients with psychiatric conditions.5 Current advances in technology now offer precise analyses of thousands of metabolites, enabling metabolomics to offer the promise of discovering new drug targets and biomarkers that may help pave a way to precision medicine.

The “human microbiota” describes all microorganisms within the human body, including bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotes. The related term “microbiome” refers to the complete catalog of these microbes and their genes.1 There is a growing awareness that the human microbiota plays an important role in maintaining mental health, and that a disruption in its composition can contribute to manifestations of psychiatric disorders. A growing body of evidence has also linked mental health outcomes to the gut microbiome, suggesting that the gut microbiota can modulate the gut-brain axis.2

Numerous neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and acetylcholine, are produced in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and our diet is vital in sustaining and replenishing them. At the same time, our brain regulates our GI tract by secretion of hormones such as oxytocin, leptin, ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, corticotrophin-releasing factor, and a plethora of others. Dysregulation of this microbiome can lead to both physical and mental illnesses. Symptoms of psychiatric disorders, such as depression, psychosis, anxiety, and autism, can be a consequence of this dysregulation.2

Our diet can also modify the gut microorganisms and therefore many of its metabolic pathways. More attention has been given to pre- and probiotics and their effects on DNA by epigenetic changes. One can quickly start to appreciate how this intricate crosstalk can lead to a variety of pathologic and psychiatric problems that have an adverse effect on autoimmune, inflammatory, metabolic, cognitive, and behavioral processes.2,3