User login

Psychotherapy for psychiatric disorders: A review of 4 studies

Psychotherapy is among the evidence-based treatment options for treating various psychiatric disorders. How we approach psychiatric disorders via psychotherapy has been shaped by numerous theories of personality and psychopathology, including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, systems, and existential-humanistic approaches. Whether used as primary treatment or in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy has played a pivotal role in shaping psychiatric disease management and treatment. Several evidence-based therapy modalities have been used throughout the years and continue to significantly improve and impact our patients’ lives. In the armamentarium of treatment modalities, therapy takes the leading role for several conditions. Here we review 4 studies from current psychotherapy literature; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-4

1.

Panic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 3.7% in the general population. Three treatment modalities recommended for patients with panic disorder are psychological therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and self-help. Among the psychological therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used.1

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder has been proven to be an efficacious and impactful treatment. For panic disorder, CBT may consist of different combinations of several therapeutic components, such as relaxation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and/or in vivo exposure. It is therefore important, both theoretically and clinically, to examine whether specific components of CBT or their combinations are superior to others for treating panic disorder.1

Pompoli et al1 conducted a component network meta-analysis (NMA) of 72 studies in order to determine which CBT components were the most efficacious in treating patients with panic disorder. Component NMA is an extension of standard NMA; it is used to disentangle the treatment effects of different components included in composite interventions.1

The aim of this study was to determine which specific component or combination of components was superior to others when treating panic disorder.1

Study design

- Researchers reviewed 2,526 references from Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central and selected 72 studies that included 4,064 patients with panic disorder.1

- The primary outcome was remission of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the short term (3 to 6 months). Remission was defined as achieving a score of ≤7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).1

- Secondary outcomes included response (≥40% reduction in PDSS score from baseline) and dropout for any reason in the short term.1

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Using component NMA, researchers determined that interoceptive exposure and face-to-face setting (administration of therapeutic components in a face-to-face setting rather than through self-help means) led to better efficacy and acceptability. Muscle relaxation and virtual reality exposure corresponded to lower efficacy. Breathing retraining and in vivo exposure improved treatment acceptability, but had small effects on efficacy.1

- Based on an analysis of remission rates, the most efficacious CBT incorporated cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure. The least efficacious CBT incorporated breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, in vivo exposure, and virtual reality exposure.1

- Application of cognitive and behavioral therapeutic elements was superior to administration of behavioral elements alone. When administering CBT, face-to-face therapy led to better outcomes in response and remission rates. Dropout rates occurred at a lower frequency when CBT was administered face-to-face when compared with self-help groups. The placebo effect was associated with the highest dropout rate.1

Conclusion

- Findings from this meta-analysis have high practical utility. Which CBT components are used can significantly alter CBT’s efficacy and acceptability in patients with panic disorder.1

- The “most efficacious CBT” would include cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure delivered in a face-to-face setting. Breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, and virtual reality may have a minimal or even negative impact.1

- Limitations of this meta-analysis include the high number of studies used for the data analysis, complex statistical analysis, inability to include unpublished studies, and limited relevant studies. A future implication of this study is the consideration of formal methodology based on the clinical application of efficacious CBT components when treating patients with panic disorder.1

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

Psychotherapy is also a useful modality for treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Sloan et al2 compared brief exposure-based treatment with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for PTSD.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of PTSD and acute stress disorder recommend the use of individual, trauma-focused therapies that focus on exposure and cognitive restructuring, such as prolonged exposure, CPT, and written narrative exposure.5

Continue to: One type of written narrative...

One type of written narrative exposure treatment is written exposure therapy (WET), which consists of 5 sessions during which patients write about their trauma. The first session is comprised of psychoeducation about PTSD and a review of treatment reasoning, followed by 30 minutes of writing. The therapist provides feedback and instructions. Written exposure therapy requires less therapist training and less supervision than prolonged exposure or CPT. Prior studies have suggested that WET can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in various trauma survivors.2

Although efficacious for PTSD, WET had not been compared with CPT, which is the most commonly used first-line treatment of PTSD. The aim of this study was to determine whether WET is noninferior to CPT.2

Study design

- In this randomized noninferiority clinical trial conducted in Boston, Massachusetts from February 28, 2013 to November 6, 2016, 126 veterans and non-veteran adults were randomized to WET or CPT. Participants met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD and were taking stable doses of their medications for at least 4 weeks.2

- Participants assigned to CPT (n = 63) underwent 12 sessions, and participants assigned to WET (n = 63) received 5 sessions. Cognitive processing therapy was conducted over 60-minute weekly sessions. Written exposure therapy consisted of an initial session that was 60 minutes long and four 40-minute follow-up sessions.2

- Interviews were conducted by 4 independent evaluators at baseline and 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks. During the WET sessions, participants wrote about a traumatic event while focusing on details, thoughts, and feelings associated with the event.2

- Cognitive processing therapy involved 12 trauma-focused therapy sessions during which participants learn how to become aware of and address problematic cognitions about the trauma as well as thoughts about themselves and others. Between sessions, participants were required to write 2 trauma accounts and complete other assignments.2

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was change in total score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). The CAPS-5 scores for participants in the WET group were noninferior to those for participants in the CPT group at all assessment points.2

- Participants did not significantly differ in age, education, income, or PTSD severity. Participants in the 2 groups did not differ in treatment expectations or level of satisfaction with treatment. Individuals assigned to CPT were more likely to drop out of the study: 20 participants in the CPT group dropped out in the first 5 sessions, whereas only 4 dropped out of the WET group. The dropout rate in the CPT group was 39.7%. Improvements in PTSD symptoms in the WET group were noninferior to improvements in the CPT group.2

- Written exposure therapy showed no difference compared with CPT in decreasing PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that PTSD symptoms can decrease with a smaller number of shorter therapeutic sessions.2

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated noninferiority between an established, commonly used PTSD therapy (CPT) and a version of exposure therapy that is briefer, simpler, and requires less homework and less therapist training and expertise. This “lower-dose” approach may improve access for the expanding number of patients who require treatment for PTSD, especially in the Veterans Affairs system.2

- In summary, WET is well tolerated and time-efficient. Although it requires fewer sessions, WET was noninferior to CPT.2

Continue to: Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual...

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive, family-based, home-based intervention for young people with serious antisocial behavior. It has been found effective for childhood conduct disorders in the United States. However, previous studies that supported its efficacy were conducted by the therapy’s developers and used noncomprehensive comparators, such as individual therapy. Fonagy et al3 assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MST vs management as usual for treating adolescent antisocial behavior. This is the first study that was performed by independent investigators and used a comprehensive control.3

Study design

- This 18-month, multisite, pragmatic, randomized controlled superiority trial was conducted in England.3

- Participants were age 11 to 17, with moderate to severe antisocial behavior. They had at least 3 severity criteria indicating difficulties across several settings and at least one of the 5 inclusion criteria for antisocial behavior. Six hundred eighty-four families were randomly assigned to MST or management as usual, and 491 families completed the study.3

- For the MST intervention, therapists worked with the adolescent’s caregiver 3 times a week for 3 to 5 months to improve parenting skills, enhance family relationships, increase support from social networks, develop skills and resources, address communication problems, increase school attendance and achievement, and reduce the adolescent’s association with delinquent peers.3

- For the management as usual intervention, management was based on local services for young people and was designed to be in line with current community practice.3

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in out-of-home placements at 18 months. The secondary outcomes were time to first criminal offense and the total number of offenses.3

- In terms of the risk of out-of-home placement, MST had no effect: 13% of participants in the MST group had out-of-home placement at 18 months, compared with 11% in the management-as-usual group.3

- Multisystemic therapy also did not significantly delay the time to first offense (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.33). Also, at 18-month follow-up, participants in the MST group had committed more offenses than those in the management-as-usual group, although the difference was not statistically significant.3

- Parents in the MST group reported increased parental support and involvement and reduced problems at 6 months, but the adolescents’ reports of parenting behavior indicated no significant effect for MST vs management as usual at any time point.3

Conclusion

- Multisystemic therapy was not superior to management as usual in reducing out-of-home placements. Although the parents believed that MST brought about a rapid and effective change, this was not reflected in objective indicators of antisocial behavior. These results are contrary to previous studies in the United States. The substantial improvements observed in both groups reflected the effectiveness of routinely offered interventions for this group of young people, at least when observed in clinical trials.3

Continue to: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy...

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

There is empirical support for using psychotherapy to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although medication management plays a leading role in treating ADHD, Janssen et al4 conducted a multicenter, single-blind trial comparing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) vs treatment as usual (TAU) for ADHD.

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of MBCT plus TAU vs TAU only in decreasing symptoms of adults with ADHD.4

Study design

- This multicenter, single-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted in the Netherlands. Participants (N = 120) met criteria for ADHD and were age ≥18. Patients were randomly assigned to MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU only (n = 60). Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group received weekly group therapy sessions, meditation exercises, psychoeducation, and group discussions. Patients in the TAU-only group received pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation.4

- Blinded clinicians used the Connors’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale to assess ADHD symptoms.4

- Secondary outcomes were determined by self-reported questionnaires that patients completed online.4

- All statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat sample as well as the per protocol sample.4

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was ADHD symptoms rated by clinicians. Secondary outcomes included self-reported ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, mindfulness skills, positive mental health, and general functioning. Outcomes were examined at baseline and then at post treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-up.4

- Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had a significant decrease in clinician-rated ADHD symptoms that was maintained at 6-month follow-up. More patients in the MBCT plus TAU group (27%) vs patients in the TAU group (4%) showed a ≥30% reduction in ADHD symptoms. Compared with patients in the TAU group, patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had significant improvements in ADHD symptoms, mindfulness skills, and positive mental health at post treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Compared with those receiving TAU only, patients treated with MBCT plus TAU reported no improvement in executive functioning at post treatment, but did improve at 6-month follow-up.4

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with TAU only, MBCT plus TAU is more effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, with a lasting effect at 6-month follow-up. In terms of secondary outcomes, MBCT plus TAU proved to be effective in improving mindfulness, self-compassion, positive mental health, and executive functioning. The results of this trial demonstrate that psychosocial treatments can be effective in addition to TAU in patients with ADHD, and MBCT holds promise for adult ADHD.4

1. Pompoli A, Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(12):1945-1953.

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder . https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed September 8, 2019.

Psychotherapy is among the evidence-based treatment options for treating various psychiatric disorders. How we approach psychiatric disorders via psychotherapy has been shaped by numerous theories of personality and psychopathology, including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, systems, and existential-humanistic approaches. Whether used as primary treatment or in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy has played a pivotal role in shaping psychiatric disease management and treatment. Several evidence-based therapy modalities have been used throughout the years and continue to significantly improve and impact our patients’ lives. In the armamentarium of treatment modalities, therapy takes the leading role for several conditions. Here we review 4 studies from current psychotherapy literature; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-4

1.

Panic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 3.7% in the general population. Three treatment modalities recommended for patients with panic disorder are psychological therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and self-help. Among the psychological therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used.1

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder has been proven to be an efficacious and impactful treatment. For panic disorder, CBT may consist of different combinations of several therapeutic components, such as relaxation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and/or in vivo exposure. It is therefore important, both theoretically and clinically, to examine whether specific components of CBT or their combinations are superior to others for treating panic disorder.1

Pompoli et al1 conducted a component network meta-analysis (NMA) of 72 studies in order to determine which CBT components were the most efficacious in treating patients with panic disorder. Component NMA is an extension of standard NMA; it is used to disentangle the treatment effects of different components included in composite interventions.1

The aim of this study was to determine which specific component or combination of components was superior to others when treating panic disorder.1

Study design

- Researchers reviewed 2,526 references from Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central and selected 72 studies that included 4,064 patients with panic disorder.1

- The primary outcome was remission of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the short term (3 to 6 months). Remission was defined as achieving a score of ≤7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).1

- Secondary outcomes included response (≥40% reduction in PDSS score from baseline) and dropout for any reason in the short term.1

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Using component NMA, researchers determined that interoceptive exposure and face-to-face setting (administration of therapeutic components in a face-to-face setting rather than through self-help means) led to better efficacy and acceptability. Muscle relaxation and virtual reality exposure corresponded to lower efficacy. Breathing retraining and in vivo exposure improved treatment acceptability, but had small effects on efficacy.1

- Based on an analysis of remission rates, the most efficacious CBT incorporated cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure. The least efficacious CBT incorporated breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, in vivo exposure, and virtual reality exposure.1

- Application of cognitive and behavioral therapeutic elements was superior to administration of behavioral elements alone. When administering CBT, face-to-face therapy led to better outcomes in response and remission rates. Dropout rates occurred at a lower frequency when CBT was administered face-to-face when compared with self-help groups. The placebo effect was associated with the highest dropout rate.1

Conclusion

- Findings from this meta-analysis have high practical utility. Which CBT components are used can significantly alter CBT’s efficacy and acceptability in patients with panic disorder.1

- The “most efficacious CBT” would include cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure delivered in a face-to-face setting. Breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, and virtual reality may have a minimal or even negative impact.1

- Limitations of this meta-analysis include the high number of studies used for the data analysis, complex statistical analysis, inability to include unpublished studies, and limited relevant studies. A future implication of this study is the consideration of formal methodology based on the clinical application of efficacious CBT components when treating patients with panic disorder.1

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

Psychotherapy is also a useful modality for treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Sloan et al2 compared brief exposure-based treatment with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for PTSD.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of PTSD and acute stress disorder recommend the use of individual, trauma-focused therapies that focus on exposure and cognitive restructuring, such as prolonged exposure, CPT, and written narrative exposure.5

Continue to: One type of written narrative...

One type of written narrative exposure treatment is written exposure therapy (WET), which consists of 5 sessions during which patients write about their trauma. The first session is comprised of psychoeducation about PTSD and a review of treatment reasoning, followed by 30 minutes of writing. The therapist provides feedback and instructions. Written exposure therapy requires less therapist training and less supervision than prolonged exposure or CPT. Prior studies have suggested that WET can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in various trauma survivors.2

Although efficacious for PTSD, WET had not been compared with CPT, which is the most commonly used first-line treatment of PTSD. The aim of this study was to determine whether WET is noninferior to CPT.2

Study design

- In this randomized noninferiority clinical trial conducted in Boston, Massachusetts from February 28, 2013 to November 6, 2016, 126 veterans and non-veteran adults were randomized to WET or CPT. Participants met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD and were taking stable doses of their medications for at least 4 weeks.2

- Participants assigned to CPT (n = 63) underwent 12 sessions, and participants assigned to WET (n = 63) received 5 sessions. Cognitive processing therapy was conducted over 60-minute weekly sessions. Written exposure therapy consisted of an initial session that was 60 minutes long and four 40-minute follow-up sessions.2

- Interviews were conducted by 4 independent evaluators at baseline and 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks. During the WET sessions, participants wrote about a traumatic event while focusing on details, thoughts, and feelings associated with the event.2

- Cognitive processing therapy involved 12 trauma-focused therapy sessions during which participants learn how to become aware of and address problematic cognitions about the trauma as well as thoughts about themselves and others. Between sessions, participants were required to write 2 trauma accounts and complete other assignments.2

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was change in total score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). The CAPS-5 scores for participants in the WET group were noninferior to those for participants in the CPT group at all assessment points.2

- Participants did not significantly differ in age, education, income, or PTSD severity. Participants in the 2 groups did not differ in treatment expectations or level of satisfaction with treatment. Individuals assigned to CPT were more likely to drop out of the study: 20 participants in the CPT group dropped out in the first 5 sessions, whereas only 4 dropped out of the WET group. The dropout rate in the CPT group was 39.7%. Improvements in PTSD symptoms in the WET group were noninferior to improvements in the CPT group.2

- Written exposure therapy showed no difference compared with CPT in decreasing PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that PTSD symptoms can decrease with a smaller number of shorter therapeutic sessions.2

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated noninferiority between an established, commonly used PTSD therapy (CPT) and a version of exposure therapy that is briefer, simpler, and requires less homework and less therapist training and expertise. This “lower-dose” approach may improve access for the expanding number of patients who require treatment for PTSD, especially in the Veterans Affairs system.2

- In summary, WET is well tolerated and time-efficient. Although it requires fewer sessions, WET was noninferior to CPT.2

Continue to: Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual...

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive, family-based, home-based intervention for young people with serious antisocial behavior. It has been found effective for childhood conduct disorders in the United States. However, previous studies that supported its efficacy were conducted by the therapy’s developers and used noncomprehensive comparators, such as individual therapy. Fonagy et al3 assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MST vs management as usual for treating adolescent antisocial behavior. This is the first study that was performed by independent investigators and used a comprehensive control.3

Study design

- This 18-month, multisite, pragmatic, randomized controlled superiority trial was conducted in England.3

- Participants were age 11 to 17, with moderate to severe antisocial behavior. They had at least 3 severity criteria indicating difficulties across several settings and at least one of the 5 inclusion criteria for antisocial behavior. Six hundred eighty-four families were randomly assigned to MST or management as usual, and 491 families completed the study.3

- For the MST intervention, therapists worked with the adolescent’s caregiver 3 times a week for 3 to 5 months to improve parenting skills, enhance family relationships, increase support from social networks, develop skills and resources, address communication problems, increase school attendance and achievement, and reduce the adolescent’s association with delinquent peers.3

- For the management as usual intervention, management was based on local services for young people and was designed to be in line with current community practice.3

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in out-of-home placements at 18 months. The secondary outcomes were time to first criminal offense and the total number of offenses.3

- In terms of the risk of out-of-home placement, MST had no effect: 13% of participants in the MST group had out-of-home placement at 18 months, compared with 11% in the management-as-usual group.3

- Multisystemic therapy also did not significantly delay the time to first offense (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.33). Also, at 18-month follow-up, participants in the MST group had committed more offenses than those in the management-as-usual group, although the difference was not statistically significant.3

- Parents in the MST group reported increased parental support and involvement and reduced problems at 6 months, but the adolescents’ reports of parenting behavior indicated no significant effect for MST vs management as usual at any time point.3

Conclusion

- Multisystemic therapy was not superior to management as usual in reducing out-of-home placements. Although the parents believed that MST brought about a rapid and effective change, this was not reflected in objective indicators of antisocial behavior. These results are contrary to previous studies in the United States. The substantial improvements observed in both groups reflected the effectiveness of routinely offered interventions for this group of young people, at least when observed in clinical trials.3

Continue to: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy...

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

There is empirical support for using psychotherapy to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although medication management plays a leading role in treating ADHD, Janssen et al4 conducted a multicenter, single-blind trial comparing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) vs treatment as usual (TAU) for ADHD.

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of MBCT plus TAU vs TAU only in decreasing symptoms of adults with ADHD.4

Study design

- This multicenter, single-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted in the Netherlands. Participants (N = 120) met criteria for ADHD and were age ≥18. Patients were randomly assigned to MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU only (n = 60). Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group received weekly group therapy sessions, meditation exercises, psychoeducation, and group discussions. Patients in the TAU-only group received pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation.4

- Blinded clinicians used the Connors’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale to assess ADHD symptoms.4

- Secondary outcomes were determined by self-reported questionnaires that patients completed online.4

- All statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat sample as well as the per protocol sample.4

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was ADHD symptoms rated by clinicians. Secondary outcomes included self-reported ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, mindfulness skills, positive mental health, and general functioning. Outcomes were examined at baseline and then at post treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-up.4

- Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had a significant decrease in clinician-rated ADHD symptoms that was maintained at 6-month follow-up. More patients in the MBCT plus TAU group (27%) vs patients in the TAU group (4%) showed a ≥30% reduction in ADHD symptoms. Compared with patients in the TAU group, patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had significant improvements in ADHD symptoms, mindfulness skills, and positive mental health at post treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Compared with those receiving TAU only, patients treated with MBCT plus TAU reported no improvement in executive functioning at post treatment, but did improve at 6-month follow-up.4

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with TAU only, MBCT plus TAU is more effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, with a lasting effect at 6-month follow-up. In terms of secondary outcomes, MBCT plus TAU proved to be effective in improving mindfulness, self-compassion, positive mental health, and executive functioning. The results of this trial demonstrate that psychosocial treatments can be effective in addition to TAU in patients with ADHD, and MBCT holds promise for adult ADHD.4

Psychotherapy is among the evidence-based treatment options for treating various psychiatric disorders. How we approach psychiatric disorders via psychotherapy has been shaped by numerous theories of personality and psychopathology, including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, systems, and existential-humanistic approaches. Whether used as primary treatment or in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy has played a pivotal role in shaping psychiatric disease management and treatment. Several evidence-based therapy modalities have been used throughout the years and continue to significantly improve and impact our patients’ lives. In the armamentarium of treatment modalities, therapy takes the leading role for several conditions. Here we review 4 studies from current psychotherapy literature; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-4

1.

Panic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 3.7% in the general population. Three treatment modalities recommended for patients with panic disorder are psychological therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and self-help. Among the psychological therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used.1

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder has been proven to be an efficacious and impactful treatment. For panic disorder, CBT may consist of different combinations of several therapeutic components, such as relaxation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and/or in vivo exposure. It is therefore important, both theoretically and clinically, to examine whether specific components of CBT or their combinations are superior to others for treating panic disorder.1

Pompoli et al1 conducted a component network meta-analysis (NMA) of 72 studies in order to determine which CBT components were the most efficacious in treating patients with panic disorder. Component NMA is an extension of standard NMA; it is used to disentangle the treatment effects of different components included in composite interventions.1

The aim of this study was to determine which specific component or combination of components was superior to others when treating panic disorder.1

Study design

- Researchers reviewed 2,526 references from Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central and selected 72 studies that included 4,064 patients with panic disorder.1

- The primary outcome was remission of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the short term (3 to 6 months). Remission was defined as achieving a score of ≤7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).1

- Secondary outcomes included response (≥40% reduction in PDSS score from baseline) and dropout for any reason in the short term.1

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Using component NMA, researchers determined that interoceptive exposure and face-to-face setting (administration of therapeutic components in a face-to-face setting rather than through self-help means) led to better efficacy and acceptability. Muscle relaxation and virtual reality exposure corresponded to lower efficacy. Breathing retraining and in vivo exposure improved treatment acceptability, but had small effects on efficacy.1

- Based on an analysis of remission rates, the most efficacious CBT incorporated cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure. The least efficacious CBT incorporated breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, in vivo exposure, and virtual reality exposure.1

- Application of cognitive and behavioral therapeutic elements was superior to administration of behavioral elements alone. When administering CBT, face-to-face therapy led to better outcomes in response and remission rates. Dropout rates occurred at a lower frequency when CBT was administered face-to-face when compared with self-help groups. The placebo effect was associated with the highest dropout rate.1

Conclusion

- Findings from this meta-analysis have high practical utility. Which CBT components are used can significantly alter CBT’s efficacy and acceptability in patients with panic disorder.1

- The “most efficacious CBT” would include cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure delivered in a face-to-face setting. Breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, and virtual reality may have a minimal or even negative impact.1

- Limitations of this meta-analysis include the high number of studies used for the data analysis, complex statistical analysis, inability to include unpublished studies, and limited relevant studies. A future implication of this study is the consideration of formal methodology based on the clinical application of efficacious CBT components when treating patients with panic disorder.1

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

Psychotherapy is also a useful modality for treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Sloan et al2 compared brief exposure-based treatment with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for PTSD.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of PTSD and acute stress disorder recommend the use of individual, trauma-focused therapies that focus on exposure and cognitive restructuring, such as prolonged exposure, CPT, and written narrative exposure.5

Continue to: One type of written narrative...

One type of written narrative exposure treatment is written exposure therapy (WET), which consists of 5 sessions during which patients write about their trauma. The first session is comprised of psychoeducation about PTSD and a review of treatment reasoning, followed by 30 minutes of writing. The therapist provides feedback and instructions. Written exposure therapy requires less therapist training and less supervision than prolonged exposure or CPT. Prior studies have suggested that WET can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in various trauma survivors.2

Although efficacious for PTSD, WET had not been compared with CPT, which is the most commonly used first-line treatment of PTSD. The aim of this study was to determine whether WET is noninferior to CPT.2

Study design

- In this randomized noninferiority clinical trial conducted in Boston, Massachusetts from February 28, 2013 to November 6, 2016, 126 veterans and non-veteran adults were randomized to WET or CPT. Participants met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD and were taking stable doses of their medications for at least 4 weeks.2

- Participants assigned to CPT (n = 63) underwent 12 sessions, and participants assigned to WET (n = 63) received 5 sessions. Cognitive processing therapy was conducted over 60-minute weekly sessions. Written exposure therapy consisted of an initial session that was 60 minutes long and four 40-minute follow-up sessions.2

- Interviews were conducted by 4 independent evaluators at baseline and 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks. During the WET sessions, participants wrote about a traumatic event while focusing on details, thoughts, and feelings associated with the event.2

- Cognitive processing therapy involved 12 trauma-focused therapy sessions during which participants learn how to become aware of and address problematic cognitions about the trauma as well as thoughts about themselves and others. Between sessions, participants were required to write 2 trauma accounts and complete other assignments.2

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was change in total score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). The CAPS-5 scores for participants in the WET group were noninferior to those for participants in the CPT group at all assessment points.2

- Participants did not significantly differ in age, education, income, or PTSD severity. Participants in the 2 groups did not differ in treatment expectations or level of satisfaction with treatment. Individuals assigned to CPT were more likely to drop out of the study: 20 participants in the CPT group dropped out in the first 5 sessions, whereas only 4 dropped out of the WET group. The dropout rate in the CPT group was 39.7%. Improvements in PTSD symptoms in the WET group were noninferior to improvements in the CPT group.2

- Written exposure therapy showed no difference compared with CPT in decreasing PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that PTSD symptoms can decrease with a smaller number of shorter therapeutic sessions.2

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated noninferiority between an established, commonly used PTSD therapy (CPT) and a version of exposure therapy that is briefer, simpler, and requires less homework and less therapist training and expertise. This “lower-dose” approach may improve access for the expanding number of patients who require treatment for PTSD, especially in the Veterans Affairs system.2

- In summary, WET is well tolerated and time-efficient. Although it requires fewer sessions, WET was noninferior to CPT.2

Continue to: Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual...

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive, family-based, home-based intervention for young people with serious antisocial behavior. It has been found effective for childhood conduct disorders in the United States. However, previous studies that supported its efficacy were conducted by the therapy’s developers and used noncomprehensive comparators, such as individual therapy. Fonagy et al3 assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MST vs management as usual for treating adolescent antisocial behavior. This is the first study that was performed by independent investigators and used a comprehensive control.3

Study design

- This 18-month, multisite, pragmatic, randomized controlled superiority trial was conducted in England.3

- Participants were age 11 to 17, with moderate to severe antisocial behavior. They had at least 3 severity criteria indicating difficulties across several settings and at least one of the 5 inclusion criteria for antisocial behavior. Six hundred eighty-four families were randomly assigned to MST or management as usual, and 491 families completed the study.3

- For the MST intervention, therapists worked with the adolescent’s caregiver 3 times a week for 3 to 5 months to improve parenting skills, enhance family relationships, increase support from social networks, develop skills and resources, address communication problems, increase school attendance and achievement, and reduce the adolescent’s association with delinquent peers.3

- For the management as usual intervention, management was based on local services for young people and was designed to be in line with current community practice.3

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in out-of-home placements at 18 months. The secondary outcomes were time to first criminal offense and the total number of offenses.3

- In terms of the risk of out-of-home placement, MST had no effect: 13% of participants in the MST group had out-of-home placement at 18 months, compared with 11% in the management-as-usual group.3

- Multisystemic therapy also did not significantly delay the time to first offense (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.33). Also, at 18-month follow-up, participants in the MST group had committed more offenses than those in the management-as-usual group, although the difference was not statistically significant.3

- Parents in the MST group reported increased parental support and involvement and reduced problems at 6 months, but the adolescents’ reports of parenting behavior indicated no significant effect for MST vs management as usual at any time point.3

Conclusion

- Multisystemic therapy was not superior to management as usual in reducing out-of-home placements. Although the parents believed that MST brought about a rapid and effective change, this was not reflected in objective indicators of antisocial behavior. These results are contrary to previous studies in the United States. The substantial improvements observed in both groups reflected the effectiveness of routinely offered interventions for this group of young people, at least when observed in clinical trials.3

Continue to: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy...

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

There is empirical support for using psychotherapy to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although medication management plays a leading role in treating ADHD, Janssen et al4 conducted a multicenter, single-blind trial comparing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) vs treatment as usual (TAU) for ADHD.

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of MBCT plus TAU vs TAU only in decreasing symptoms of adults with ADHD.4

Study design

- This multicenter, single-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted in the Netherlands. Participants (N = 120) met criteria for ADHD and were age ≥18. Patients were randomly assigned to MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU only (n = 60). Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group received weekly group therapy sessions, meditation exercises, psychoeducation, and group discussions. Patients in the TAU-only group received pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation.4

- Blinded clinicians used the Connors’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale to assess ADHD symptoms.4

- Secondary outcomes were determined by self-reported questionnaires that patients completed online.4

- All statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat sample as well as the per protocol sample.4

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was ADHD symptoms rated by clinicians. Secondary outcomes included self-reported ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, mindfulness skills, positive mental health, and general functioning. Outcomes were examined at baseline and then at post treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-up.4

- Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had a significant decrease in clinician-rated ADHD symptoms that was maintained at 6-month follow-up. More patients in the MBCT plus TAU group (27%) vs patients in the TAU group (4%) showed a ≥30% reduction in ADHD symptoms. Compared with patients in the TAU group, patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had significant improvements in ADHD symptoms, mindfulness skills, and positive mental health at post treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Compared with those receiving TAU only, patients treated with MBCT plus TAU reported no improvement in executive functioning at post treatment, but did improve at 6-month follow-up.4

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with TAU only, MBCT plus TAU is more effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, with a lasting effect at 6-month follow-up. In terms of secondary outcomes, MBCT plus TAU proved to be effective in improving mindfulness, self-compassion, positive mental health, and executive functioning. The results of this trial demonstrate that psychosocial treatments can be effective in addition to TAU in patients with ADHD, and MBCT holds promise for adult ADHD.4

1. Pompoli A, Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(12):1945-1953.

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder . https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed September 8, 2019.

1. Pompoli A, Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(12):1945-1953.

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder . https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed September 8, 2019.

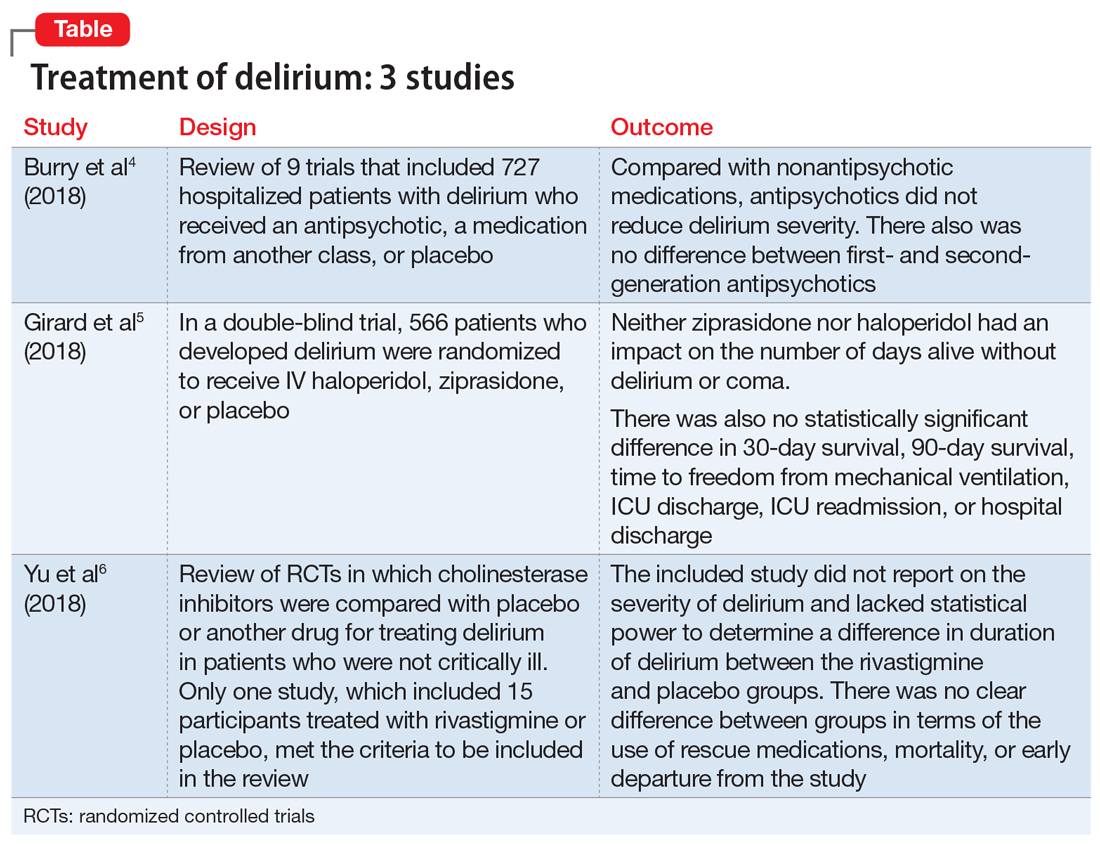

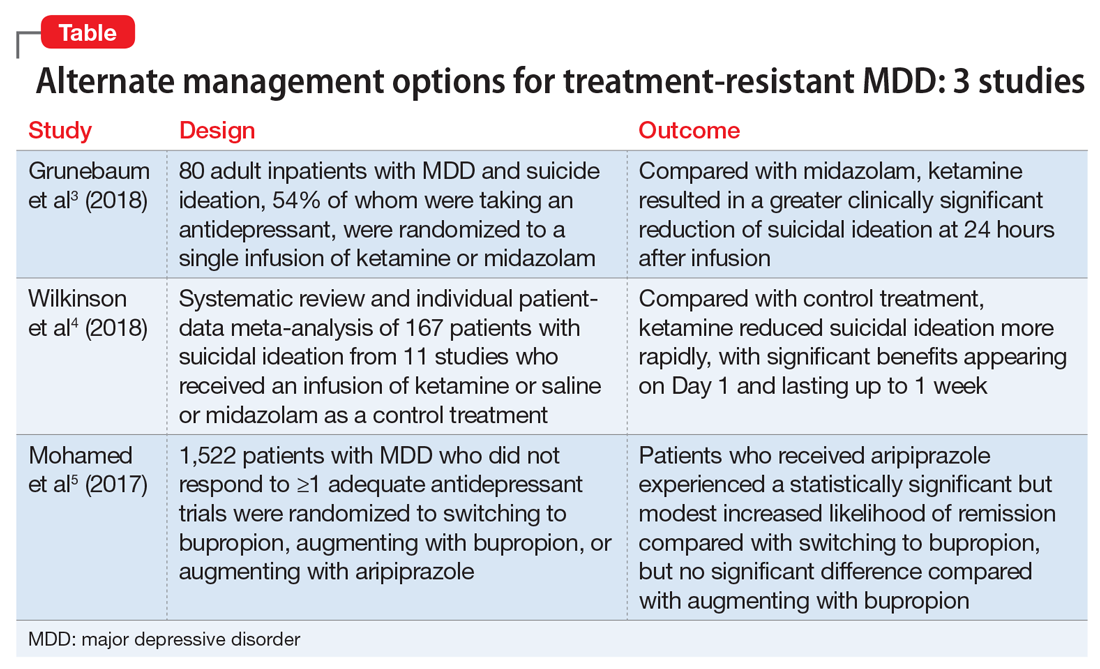

Treatment of delirium: A review of 3 studies

Delirium is defined as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition that develops over hours to days as a direct physiological consequence of an underlying medical condition and is not better explained by another neurocognitive disorder.1 This condition is found in up to 31% of general medical patients and up to 87% of critically ill medical patients. Delirium is commonly seen in patients who have undergone surgery, those who are in palliative care, and patients with cancer.2 It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Compared with those who do not develop delirium, patients who are hospitalized who develop delirium have a higher risk of longer hospital stays, post-hospitalization nursing facility placement, persistent cognitive dysfunction, and death.3

Thus far, the management and treatment of delirium have been complicated by an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition. However, prevailing theories suggest a dysregulation of neurotransmitter synthesis, function, or availability.2 Recent literature reflects this theory; researchers have investigated agents that target dopamine or acetylcholine. Below we review some of this recent literature on treating delirium; these studies are summarized in the Table.4-6

1. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594.

An extensive literature review identified randomized or quasi-randomized trials on the treatment of delirium among non-critically ill hospitalized patients in which antipsychotics were compared with nonantipsychotic medications or placebo, or in which a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) was compared with a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA).4

Study design

- Researchers conducted a literature review of 9 trials that included 727 hospitalized but not critically ill patients (ie, they were not in an ICU) who developed delirium.

- Four trials compared an antipsychotic with a medication from another drug class or with placebo.

- Seven trials compared a FGA with an SGA.

Outcomes

- Although the intended primary outcome was the duration of delirium, none of the included studies reported on duration of delirium. Secondary outcomes were delirium severity and resolution, mortality, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, health-related quality of life, and adverse effects.

- Among the secondary outcomes, no statistical difference was observed between delirium severity, delirium resolution, or mortality.

- None of the included studies reported on hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, or health-related quality of life.

- Evidence related to adverse effects was determined to be very low quality due to potential bias, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Conclusion

- A review of 9 randomized trials did not find any evidence supporting the use of antipsychotics for treating delirium. However, most of the studies included were of lower quality because they were single-center trials with insufficient sample sizes, heterogeneous study populations, and risk of bias.

Continue to: 2...

2. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

Study design

- Researchers used the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) to assess 1,183 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock in 16 medical centers in the United States.5

- Overall, 566 patients developed delirium and were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive IV haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo.

- Haloperidol was started at 2.5 mg (age <70) or 1.25 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 20 mg/d as tolerated.

- Ziprasidone was started at 5 mg (age <70) or 2.5 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 40 mg/d as tolerated.

Outcomes

- The primary endpoint was days alive without delirium or coma. Secondary endpoints included duration of delirium, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, time to final successful ICU discharge, time to ICU readmission, time to successful hospital discharge, 30-day survival, and 90-day survival.

- Neither ziprasidone nor haloperidol had an impact on number of days alive without delirium or coma.

- There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day survival, 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Conclusion

- This study found no evidence supporting haloperidol or ziprasidone for the treatment of delirium. Because all patients in this study were critically ill, it is unclear if these results would be generalizable to other hospitalized patient populations.

3. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Study design

- A literature review identified published and unpublished randomized controlled trials in English and Chinese in which cholinesterase inhibitors were compared with placebo or another drug for treating delirium in non-critically ill patients.6

- Only one study met the criteria to be included in the review. It included 15 participants treated with rivastigmine or placebo.

Outcomes

- The intended primary outcomes were severity of delirium and duration of delirium. However, the included study did not report on the severity of delirium. It also lacked statistical power to determine a difference in duration of delirium between the rivastigmine and placebo groups.

- Secondary outcomes included use of a rescue medication, persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, mortality, cost of intervention, early departure from the study, and quality of life.

- There was no clear difference between the rivastigmine group and the placebo group in terms of the use of rescue medications, mortality, or early departure from the study. The included study did not report on persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, cost of intervention, or quality of life.

Conclusion

- This literature review did not find any evidence to support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors for treating delirium. However, because this review included only a single small study, limited conclusions can be drawn from this research.

In summary, delirium is common, especially among patients who are acutely medically ill, and it is associated with poor physical and cognitive clinical outcomes. Because of these poor outcomes, it is important to identify delirium early and intervene aggressively. Clearly, there is a need for further research into short- and long-term treatments for delirium.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Maldonado JR. Acute brain failure: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, and sequelae of delirium. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):461-519.

3. Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1456-1466.

4. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005594.pub3.

5. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

6. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Delirium is defined as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition that develops over hours to days as a direct physiological consequence of an underlying medical condition and is not better explained by another neurocognitive disorder.1 This condition is found in up to 31% of general medical patients and up to 87% of critically ill medical patients. Delirium is commonly seen in patients who have undergone surgery, those who are in palliative care, and patients with cancer.2 It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Compared with those who do not develop delirium, patients who are hospitalized who develop delirium have a higher risk of longer hospital stays, post-hospitalization nursing facility placement, persistent cognitive dysfunction, and death.3

Thus far, the management and treatment of delirium have been complicated by an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition. However, prevailing theories suggest a dysregulation of neurotransmitter synthesis, function, or availability.2 Recent literature reflects this theory; researchers have investigated agents that target dopamine or acetylcholine. Below we review some of this recent literature on treating delirium; these studies are summarized in the Table.4-6

1. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594.

An extensive literature review identified randomized or quasi-randomized trials on the treatment of delirium among non-critically ill hospitalized patients in which antipsychotics were compared with nonantipsychotic medications or placebo, or in which a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) was compared with a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA).4

Study design

- Researchers conducted a literature review of 9 trials that included 727 hospitalized but not critically ill patients (ie, they were not in an ICU) who developed delirium.

- Four trials compared an antipsychotic with a medication from another drug class or with placebo.

- Seven trials compared a FGA with an SGA.

Outcomes

- Although the intended primary outcome was the duration of delirium, none of the included studies reported on duration of delirium. Secondary outcomes were delirium severity and resolution, mortality, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, health-related quality of life, and adverse effects.

- Among the secondary outcomes, no statistical difference was observed between delirium severity, delirium resolution, or mortality.

- None of the included studies reported on hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, or health-related quality of life.

- Evidence related to adverse effects was determined to be very low quality due to potential bias, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Conclusion

- A review of 9 randomized trials did not find any evidence supporting the use of antipsychotics for treating delirium. However, most of the studies included were of lower quality because they were single-center trials with insufficient sample sizes, heterogeneous study populations, and risk of bias.

Continue to: 2...

2. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

Study design

- Researchers used the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) to assess 1,183 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock in 16 medical centers in the United States.5

- Overall, 566 patients developed delirium and were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive IV haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo.

- Haloperidol was started at 2.5 mg (age <70) or 1.25 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 20 mg/d as tolerated.

- Ziprasidone was started at 5 mg (age <70) or 2.5 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 40 mg/d as tolerated.

Outcomes

- The primary endpoint was days alive without delirium or coma. Secondary endpoints included duration of delirium, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, time to final successful ICU discharge, time to ICU readmission, time to successful hospital discharge, 30-day survival, and 90-day survival.

- Neither ziprasidone nor haloperidol had an impact on number of days alive without delirium or coma.

- There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day survival, 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Conclusion

- This study found no evidence supporting haloperidol or ziprasidone for the treatment of delirium. Because all patients in this study were critically ill, it is unclear if these results would be generalizable to other hospitalized patient populations.

3. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Study design

- A literature review identified published and unpublished randomized controlled trials in English and Chinese in which cholinesterase inhibitors were compared with placebo or another drug for treating delirium in non-critically ill patients.6

- Only one study met the criteria to be included in the review. It included 15 participants treated with rivastigmine or placebo.

Outcomes

- The intended primary outcomes were severity of delirium and duration of delirium. However, the included study did not report on the severity of delirium. It also lacked statistical power to determine a difference in duration of delirium between the rivastigmine and placebo groups.

- Secondary outcomes included use of a rescue medication, persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, mortality, cost of intervention, early departure from the study, and quality of life.

- There was no clear difference between the rivastigmine group and the placebo group in terms of the use of rescue medications, mortality, or early departure from the study. The included study did not report on persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, cost of intervention, or quality of life.

Conclusion

- This literature review did not find any evidence to support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors for treating delirium. However, because this review included only a single small study, limited conclusions can be drawn from this research.

In summary, delirium is common, especially among patients who are acutely medically ill, and it is associated with poor physical and cognitive clinical outcomes. Because of these poor outcomes, it is important to identify delirium early and intervene aggressively. Clearly, there is a need for further research into short- and long-term treatments for delirium.

Delirium is defined as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition that develops over hours to days as a direct physiological consequence of an underlying medical condition and is not better explained by another neurocognitive disorder.1 This condition is found in up to 31% of general medical patients and up to 87% of critically ill medical patients. Delirium is commonly seen in patients who have undergone surgery, those who are in palliative care, and patients with cancer.2 It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Compared with those who do not develop delirium, patients who are hospitalized who develop delirium have a higher risk of longer hospital stays, post-hospitalization nursing facility placement, persistent cognitive dysfunction, and death.3

Thus far, the management and treatment of delirium have been complicated by an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition. However, prevailing theories suggest a dysregulation of neurotransmitter synthesis, function, or availability.2 Recent literature reflects this theory; researchers have investigated agents that target dopamine or acetylcholine. Below we review some of this recent literature on treating delirium; these studies are summarized in the Table.4-6

1. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594.

An extensive literature review identified randomized or quasi-randomized trials on the treatment of delirium among non-critically ill hospitalized patients in which antipsychotics were compared with nonantipsychotic medications or placebo, or in which a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) was compared with a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA).4

Study design

- Researchers conducted a literature review of 9 trials that included 727 hospitalized but not critically ill patients (ie, they were not in an ICU) who developed delirium.

- Four trials compared an antipsychotic with a medication from another drug class or with placebo.

- Seven trials compared a FGA with an SGA.

Outcomes

- Although the intended primary outcome was the duration of delirium, none of the included studies reported on duration of delirium. Secondary outcomes were delirium severity and resolution, mortality, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, health-related quality of life, and adverse effects.

- Among the secondary outcomes, no statistical difference was observed between delirium severity, delirium resolution, or mortality.

- None of the included studies reported on hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, or health-related quality of life.

- Evidence related to adverse effects was determined to be very low quality due to potential bias, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Conclusion

- A review of 9 randomized trials did not find any evidence supporting the use of antipsychotics for treating delirium. However, most of the studies included were of lower quality because they were single-center trials with insufficient sample sizes, heterogeneous study populations, and risk of bias.

Continue to: 2...

2. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

Study design

- Researchers used the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) to assess 1,183 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock in 16 medical centers in the United States.5

- Overall, 566 patients developed delirium and were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive IV haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo.

- Haloperidol was started at 2.5 mg (age <70) or 1.25 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 20 mg/d as tolerated.

- Ziprasidone was started at 5 mg (age <70) or 2.5 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 40 mg/d as tolerated.

Outcomes

- The primary endpoint was days alive without delirium or coma. Secondary endpoints included duration of delirium, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, time to final successful ICU discharge, time to ICU readmission, time to successful hospital discharge, 30-day survival, and 90-day survival.

- Neither ziprasidone nor haloperidol had an impact on number of days alive without delirium or coma.

- There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day survival, 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Conclusion

- This study found no evidence supporting haloperidol or ziprasidone for the treatment of delirium. Because all patients in this study were critically ill, it is unclear if these results would be generalizable to other hospitalized patient populations.

3. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Study design

- A literature review identified published and unpublished randomized controlled trials in English and Chinese in which cholinesterase inhibitors were compared with placebo or another drug for treating delirium in non-critically ill patients.6

- Only one study met the criteria to be included in the review. It included 15 participants treated with rivastigmine or placebo.

Outcomes

- The intended primary outcomes were severity of delirium and duration of delirium. However, the included study did not report on the severity of delirium. It also lacked statistical power to determine a difference in duration of delirium between the rivastigmine and placebo groups.

- Secondary outcomes included use of a rescue medication, persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, mortality, cost of intervention, early departure from the study, and quality of life.

- There was no clear difference between the rivastigmine group and the placebo group in terms of the use of rescue medications, mortality, or early departure from the study. The included study did not report on persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, cost of intervention, or quality of life.

Conclusion

- This literature review did not find any evidence to support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors for treating delirium. However, because this review included only a single small study, limited conclusions can be drawn from this research.

In summary, delirium is common, especially among patients who are acutely medically ill, and it is associated with poor physical and cognitive clinical outcomes. Because of these poor outcomes, it is important to identify delirium early and intervene aggressively. Clearly, there is a need for further research into short- and long-term treatments for delirium.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Maldonado JR. Acute brain failure: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, and sequelae of delirium. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):461-519.

3. Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1456-1466.

4. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005594.pub3.

5. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

6. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Maldonado JR. Acute brain failure: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, and sequelae of delirium. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):461-519.

3. Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1456-1466.

4. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005594.pub3.

5. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

6. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

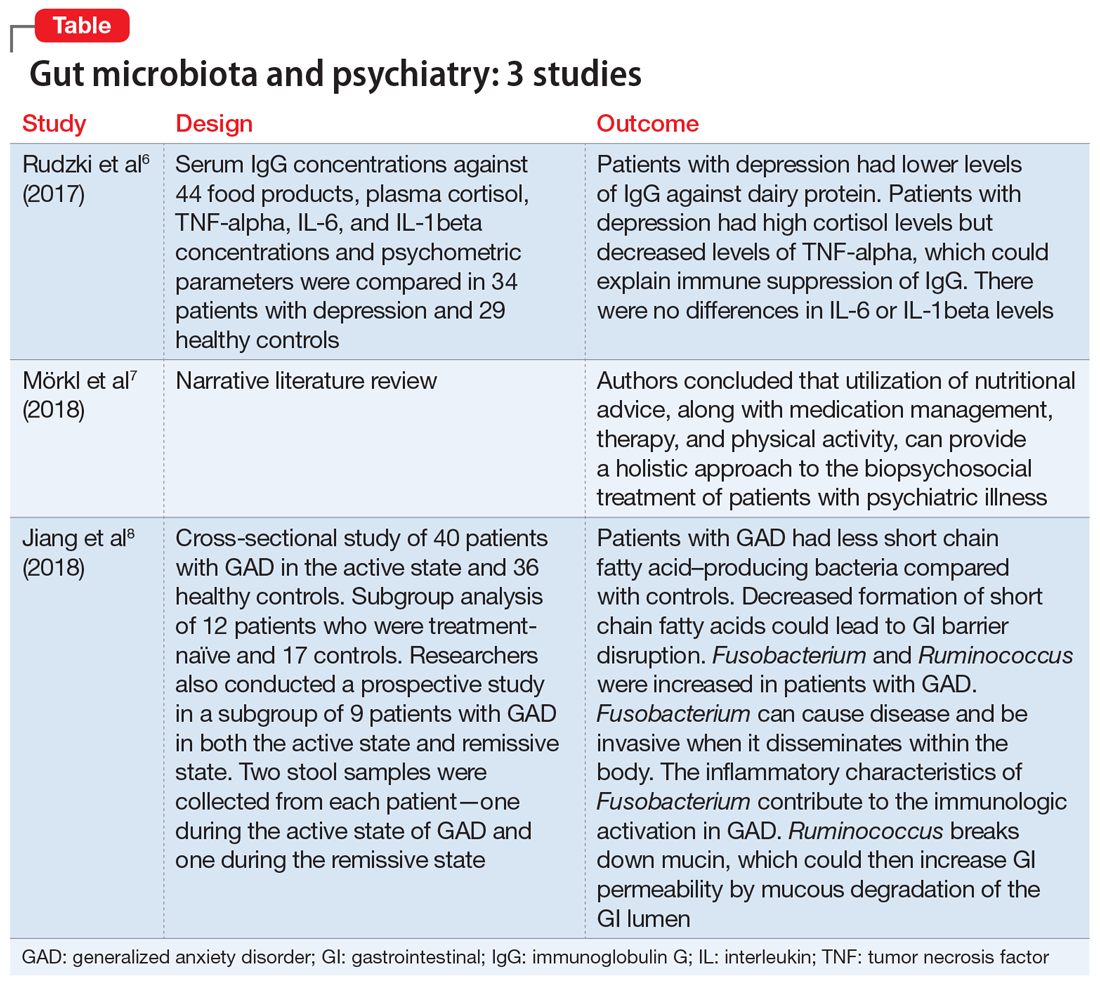

Gut microbiota and its implications for psychiatry: A review of 3 studies

The “human microbiota” describes all microorganisms within the human body, including bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotes. The related term “microbiome” refers to the complete catalog of these microbes and their genes.1 There is a growing awareness that the human microbiota plays an important role in maintaining mental health, and that a disruption in its composition can contribute to manifestations of psychiatric disorders. A growing body of evidence has also linked mental health outcomes to the gut microbiome, suggesting that the gut microbiota can modulate the gut-brain axis.2

Numerous neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and acetylcholine, are produced in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and our diet is vital in sustaining and replenishing them. At the same time, our brain regulates our GI tract by secretion of hormones such as oxytocin, leptin, ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, corticotrophin-releasing factor, and a plethora of others. Dysregulation of this microbiome can lead to both physical and mental illnesses. Symptoms of psychiatric disorders, such as depression, psychosis, anxiety, and autism, can be a consequence of this dysregulation.2

Our diet can also modify the gut microorganisms and therefore many of its metabolic pathways. More attention has been given to pre- and probiotics and their effects on DNA by epigenetic changes. One can quickly start to appreciate how this intricate crosstalk can lead to a variety of pathologic and psychiatric problems that have an adverse effect on autoimmune, inflammatory, metabolic, cognitive, and behavioral processes.2,3

Thus far, links have mostly been reported in animal models, and human studies are limited.4 Researchers are just beginning to elucidate how the microbiota affect gut-brain signaling in humans. Such mechanisms may include alterations in microbial composition, immune activation, vagus nerve signaling, alterations in tryptophan metabolism, production of specific microbial neuroactive metabolites, and bacterial cell wall sugars.5 The microbiota-gut-brain axis plays a part in regulating/programming the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis throughout the life span.3 The interactions between the gut microbiome, the immune system, and the CNS are regulated through pathways that involve endocrine functions (HPA axis), the immune system, and metabolic factors.3,4 Recent research focusing on the gut microbiome has also given rise to international projects such as the Human Microbiome Project (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012).3

Several studies have looked into psychiatry and inflammatory/immune pathways. Here we review 3 recent studies that have focused on the gut-brain axis (Table6-8).

1. Rudzki L, Pawlak D, Pawlak K, et al. Immune suppression of IgG response against dairy proteins in major depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):268.

The aim of this study was to evaluate immunoglobulin G (IgG) response against 40 food products in patients with depression vs those in a control group, along with changes in inflammatory markers, psychological stress, and dietary variables.6

Study design

- N = 63, IgG levels against 44 food products, cortisol levels, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-1 beta levels were recorded. The psychological parameters of 34 participants with depression and 29 controls were compared using the Hamilton Depression Rating scale, (HAM-D-17), Perceived Stress scale, and Symptom Checklist scale. The study was conducted in Poland.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Patients who were depressed had lower IgG levels against dairy products compared to controls when there was high dairy consumption. However, there was no overall difference between patients and controls in mean IgG concentration against food products.

- Patients who were depressed had higher levels of cortisol. Levels of cortisol had a positive correlation with HAM-D-17 score. Patients with depression had lower levels of TNF-alpha.

Conclusion

- Patients with depression had lower levels of IgG against dairy protein. Patients with depression had high cortisol levels but decreased levels of TNF-alpha, which could explain an immune suppression of IgG in these patients. There were no differences in IL-6 or IL-1beta levels.