User login

Unilateral Vesicular Eruption in a Neonate

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

A 4-day-old female neonate presented to the dermatology clinic with a vesicular eruption on the left leg of 1 day's duration. The eruption was asymptomatic without any extracutaneous findings. This term infant was born without complication, and the mother denied any symptoms consistent with herpes simplex virus infection. Physical examination revealed yellow-red vesicles on an erythematous base in a blaschkoid distribution on the left leg. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction testing was negative.

Annular Atrophic Plaques on the Forearm

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

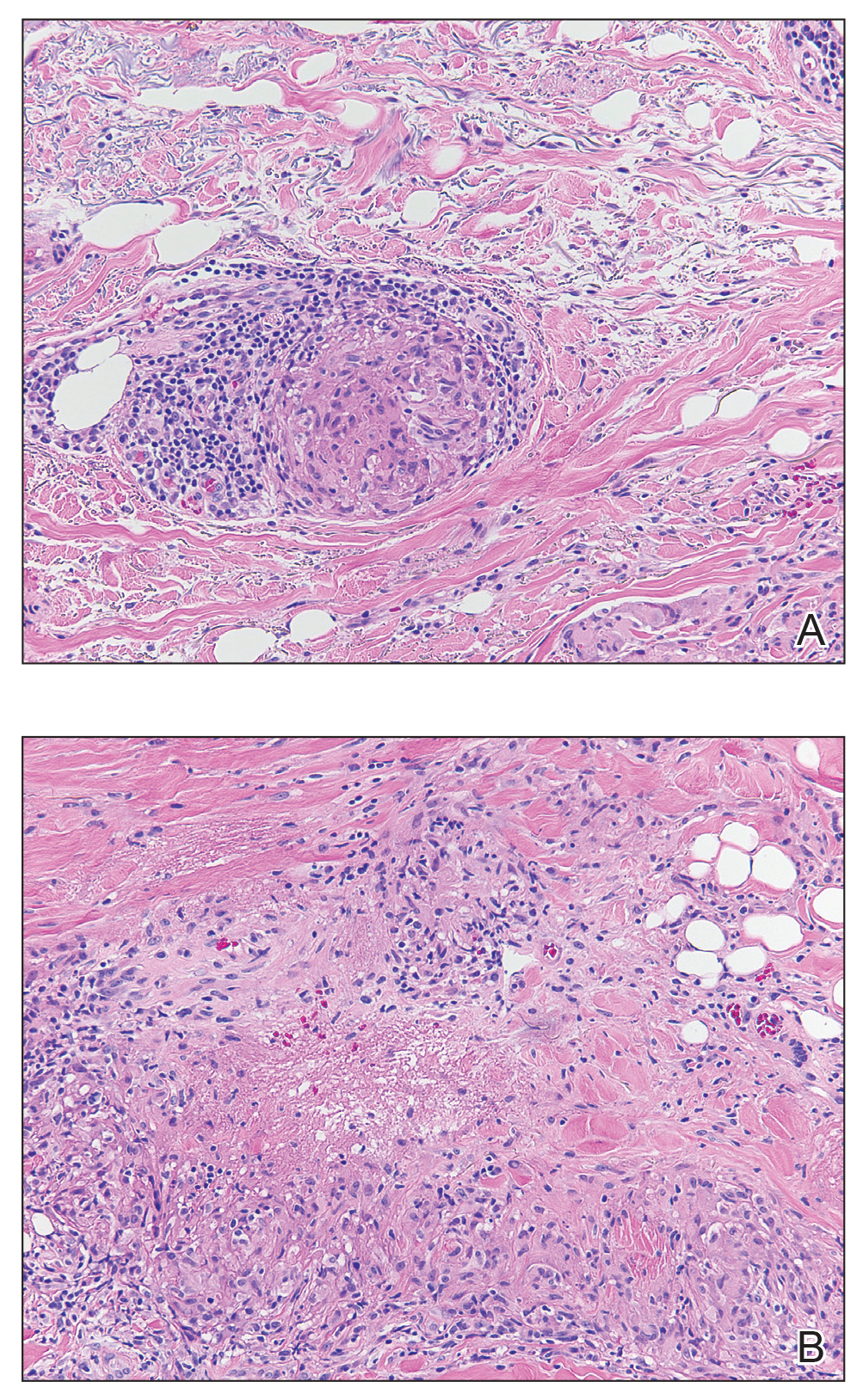

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic noncaseating granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. The skin is the second most common location for disease manifestation following the lungs.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is present in 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may be further subtyped by its morphologic characteristics (eg, hyperpigmented, papular, nodular, atrophic, ulcerative, psoriasiform). Cutaneous sarcoidosis has an increased tendency to occur at areas of prior injury such as surgeries or tattoos.2 Although sarcoidosis affects all races and sexes, it is more prevalent in women and in the black population.3

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is difficult due to its morphologic variation, allowing for a wide differential diagnosis. With our patient’s presentation of atrophic plaques, the differential diagnosis included granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, tumid lupus erythematosus, leprosy, and sarcoidosis; however, biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. The characteristic histopathology for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes noncaseating granulomas (Figure, A) composed of epithelioid histiocytes with giant cells surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific to sarcoidosis and are present in 71% to 89% of biopsied lesions.4 Interestingly, our patient presented with a rare subtype of atrophic ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis, which is more common in females and in the black population. It is characterized by pink to violaceous plaques with depressed centers and prominent necrotizing granuloma (Figure, B) on histopathology. In a small case series, all 3 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica–like sarcoidosis were female and had systemic involvement at the time of diagnosis.5

Sarcoidosis typically is a systemic disease with only a limited number of cases presenting with isolated cutaneous findings. Therefore, patients require a systemic evaluation, which may include a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, ophthalmologic examinations, thyroid testing, and vitamin D monitoring, as well as an echocardiogram and electrocardiogram.2

Treatment is guided by the severity of disease. For isolated cutaneous lesions, topical or intralesional high-potency steroids have been shown to be effective.6,7 Several studies also have shown phototherapy and laser therapy as well as surgical excision to be beneficial.8-10 Once cutaneous lesions become disfiguring or systemic involvement is found, systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory medications may be warranted.11 Our patient was started on intralesional and topical high-potency steroids, which failed, and she was transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab. Unfortunately, even with advanced therapies, our patient did not have notableresolution of the lesions.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41 (6, pt 2): E355-E374.

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med.2015; 36:685-702.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics ofpatients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10, pt 1):1885-1889.

- Ball NJ, Kho GT, Martinka M. The histologic spectrum of cutaneous sarcoidosis: a study of twenty-eight cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:160-168.

- Mendoza V, Vahid B, Kozic H, et al. Clinical and pathologic manifestations of necrobiosis lipoidica-like skin involvement in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007; 74:647-649.

- Khatri KA, Chotzen VA, Burrall BA. Lupus pernio: successful treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 1995; 131:617-618.

- Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Cutaneous sarcoidosis without systemic involvement: response to intralesional corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996; 62:273-274.

- Karrer S, Abels C, Wimmershoff MB, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis using topical photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138:581-584.

- Mahnke N, Medve-koenigs K, Berneburg M, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis treated with medium-dose UVA1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 50:978-979.

- Frederiksen LG, Jørgensen K. Sarcoidosis of the nose treated with laser surgery. Rhinology. 1996; 34:245-246.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007; 25:334-340.

A 57-year-old woman presented with several lesions on the left extensor forearm of 10 years’ duration. A single annular indurated lesion with central atrophy initially developed near a prior surgical site. The lesions were pruritic with no associated pain or bleeding. Over 5 years, similar lesions had developed extending up the arm. No benefit was seen with low-potency topical steroid application. Biopsy for histopathologic examination was performed to confirm the diagnosis.