User login

Pink Polycyclic Ulcerations on the Lower Back and Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

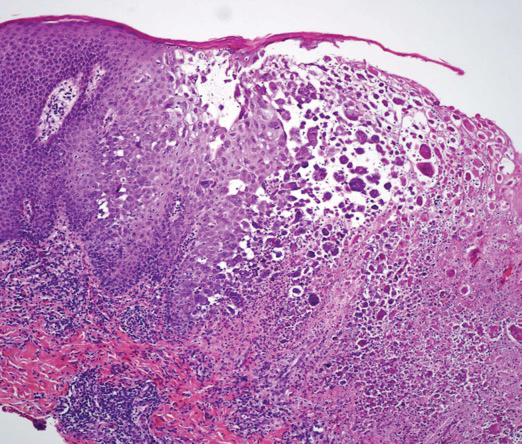

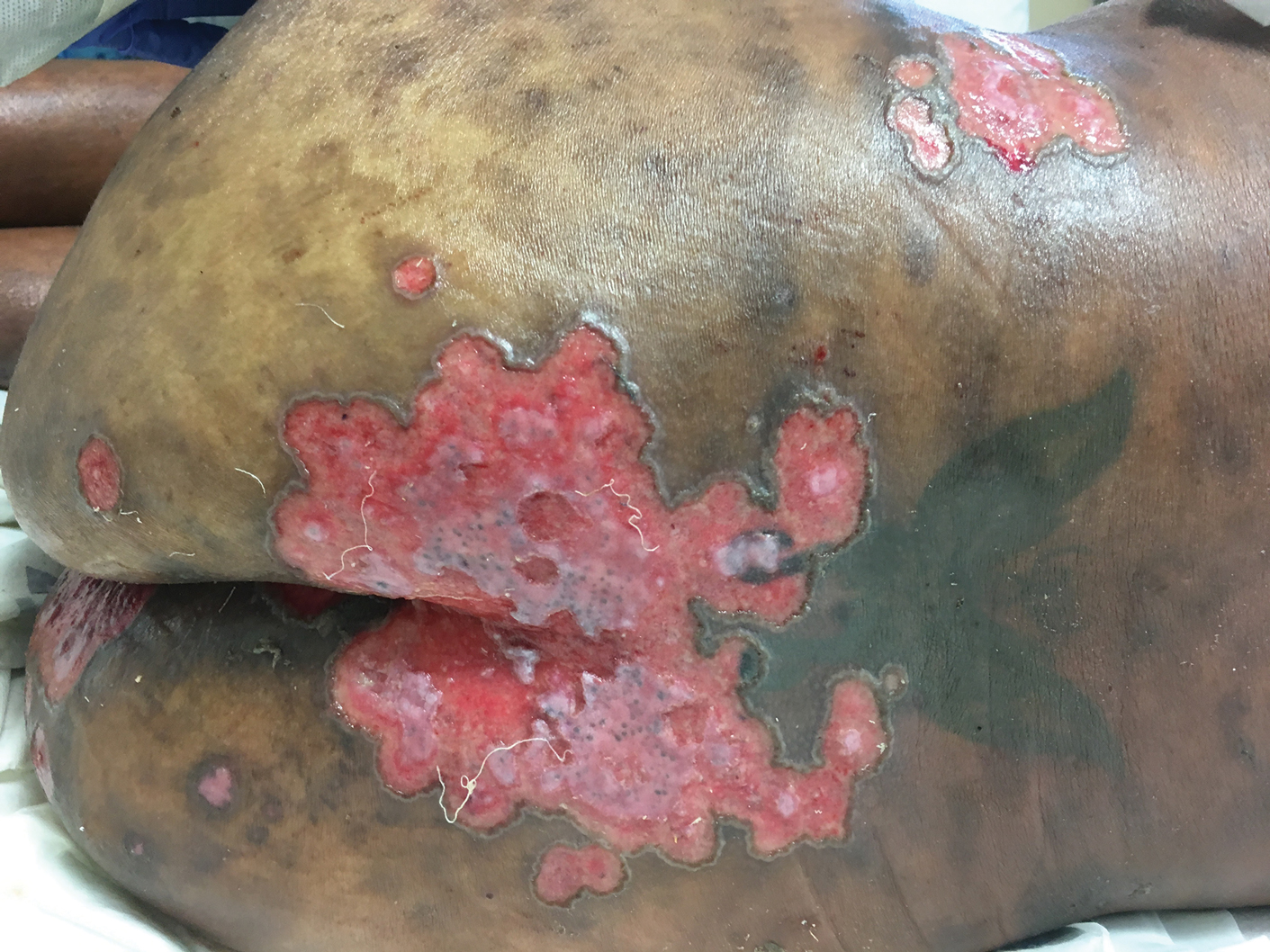

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

A 32-year-old woman with stage IV cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was admitted with pancytopenia and septic shock secondary to methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Dermatology was consulted regarding sacral ulcerations. The lesions were asymptomatic and had been slowly enlarging over the course of 1 month. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, pink, polycyclic ulcerations on the lower back and buttocks extending onto the perineum. There was no pain or tingling associated with the ulcerations. She denied a history of cold sore lesions on the lips or genitals. A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and histopathologic examination.

Diffuse erythematous rash resistant to treatment

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of diffuse redness, itching, and tenderness of her skin. The patient said the eruption began 4 months earlier as localized plaques on her scalp, elbows, and beneath both breasts. Over the course of a few days, the redness became more diffuse, affecting most of her body. She also noticed swelling and skin desquamation on her lower extremities.

The patient had visited multiple urgent care clinics and underwent several courses of prednisone with initial improvement of symptoms, but experienced recurrence shortly after finishing the tapers.

On physical examination, more than 95% of the patient’s skin was bright red and tender to the touch, with associated exfoliation (FIGURES 1A-1B). Her lower extremities had pitting edema with superficial erosions that were weeping serous fluid. She was afebrile and normotensive, but had shaking chills and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 bpm. There was no nail pitting, pustules, or lymphadenopathy. Lab tests revealed a low albumin level of 2.2 g/dL (normal: 3.5-5.5 g/dL), an elevated white blood cell count of 14,700 cells/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000 cells/mcL), and normocytic anemia (low hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL; normal: 12-15.5 g/dL). The patient was admitted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythroderma

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed severe erythroderma secondary to psoriasis. A punch biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated subacute spongiotic dermatitis with superficial neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with psoriasis.

Erythroderma is widespread reddening of the skin associated with desquamation, typically involving more than 90% of the body’s surface area.1 In most instances, erythroderma is a clinical presentation of an existing dermatosis. The most common causative conditions include primary skin disorders (such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis), idiopathic erythroderma, and drug eruptions. Less common causes include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and contact dermatitis.1

It’s unclear why some skin diseases progress to erythroderma; the pathogenesis is complicated and involves keratinocytes and lymphocytes interacting with adhesion molecules and cytokines. Erythroderma can arise at any age and occurs in all races, but is more common in males and older adults, with a mean age of 42 to 61 years.2 The annual incidence of erythroderma is estimated to be one per 100,000 adults.3

A complete picture of the patient is essential to making the diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult and hinges on historical and physical exam findings, as well as lab evaluations and skin biopsies. The history should focus on current and former medications, while the physical exam should hone in on clinical manifestations of existing dermatoses. The most common extracutaneous finding is generalized lymphadenopathy, which if prominent, may warrant lymph node biopsy, with studies for evaluation of underlying lymphoma.

Tachycardia develops in 40% of patients, secondary to increased blood flow to the skin and fluid loss, with risk of high-output cardiac failure.2 Patients often have chills because their skin is not able to regulate their body temperature normally.4

The lab evaluation should include a complete blood count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic panel, as well as blood, skin, and urine cultures if infection is suspected as an inciting factor. Typical findings include mild anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 In addition, patients with chronic erythroderma commonly have low albumin.6 Unfortunately, lab studies don’t always reveal the underlying cause of the erythroderma.

Biopsies are commonly performed. However, the underlying etiology is often not clearly reflected in the result. Histology is typically nonspecific; findings frequently include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Additionally, the prominence of histologic features may vary depending on the stage of disease and the severity of inflammation. More specific findings may become evident later in the disease as the erythroderma clears, so repeated skin biopsies over time may be needed for diagnosis.7

Consider these conditions, which can lead to erythroderma

First and foremost, it is important to get a thorough history, particularly about prior skin conditions and symptoms that may indicate the presence of undiagnosed skin conditions.

Psoriasis is one of the most common causes of erythroderma. A history of pre-existing psoriasis is very helpful, but when this is not present, a biopsy can help confirm a clinical suspicion for psoriasis. It also helps to look for clues of psoriasis like nail changes or a history of plaques over the elbows and knees.

Atopic dermatitis is another common cause of erythroderma, and the history might include scaling and erythematous patches or plaques involving flexural surfaces before erythroderma occurs. Patients may have a history of atopic dermatitis from childhood and/or a history of other atopic conditions such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Drug eruptions occur following the administration of a new medication and can mimic a myriad of dermatoses.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can lead to erythroderma and be differentiated with skin biopsy; pathology may show atypical lymphocytes, and Pautrier’s microabscesses may be seen.8

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a relatively rare condition that presents with red-orange scaling patches and thickened yellowish palms and soles.9

Tx targets underlying etiology and associated complications

When treating a patient with erythroderma, it’s important to prevent hypothermia and secondary infections. If symptoms are severe, hospitalization should be considered. Nutrition should be assessed, and any fluid or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected.

Oral antihistamines are commonly administered to suppress associated pruritus. Topical treatment usually consists of corticosteroids under occlusion with bland emollients. Depending upon the underlying disease, the following systemic medications may be started: methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg once/week; acitretin 10 to 25 mg/d; or cyclosporine 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/d; in addition to topical treatment.4

Our patient. Pathology for our patient was indicative of psoriasis. She was started on a regimen of cyclosporine 4 to 5 mg/kg/d, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg as needed for itching, triamcinolone 0.1% ointment under wet wraps to her trunk and extremities, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment to be applied to her face daily. She was released after 5 days in the hospital. At outpatient follow-up one week later, her erythroderma was resolving. One month later, her erythroderma was resolved (FIGURE 2), although she did have psoriatic plaques on her lower legs.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; Usatine@uthscsa.edu.

1. Keisham C, Sahoo B, Khurana N, et al. Clinicopathologic study of erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB85.

2. Li J, Zheng H-Y. Erythroderma: a clinical and prognostic study. Dermatology. 2012;225:154-162.

3. Sigurdsson V, Steegmans PH, van Vioten WA. The incidence of erythroderma: a survey among all dermatologists in The Netherlands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:675-678.

4. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology essentials. 1st ed. Oxford, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

5. Karakayli G, Beckham G, Orengo I, et al. Exfoliative dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:625-630.

6. Rothe MJ, Bialy TL, Grant-Kels JM. Erythroderma. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:405-415.

7. Walsh NM, Prokopetz R, Tron VA, et al. Histopathology in erythroderma: review of a series of cases by multiple observers. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:419-423.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

9. Abdel-Azim NE, Ismail SA, Fathy E. Differentiation of pityriasis rubra pilaris from plaque psoriasis by dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:311-314.

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of diffuse redness, itching, and tenderness of her skin. The patient said the eruption began 4 months earlier as localized plaques on her scalp, elbows, and beneath both breasts. Over the course of a few days, the redness became more diffuse, affecting most of her body. She also noticed swelling and skin desquamation on her lower extremities.

The patient had visited multiple urgent care clinics and underwent several courses of prednisone with initial improvement of symptoms, but experienced recurrence shortly after finishing the tapers.

On physical examination, more than 95% of the patient’s skin was bright red and tender to the touch, with associated exfoliation (FIGURES 1A-1B). Her lower extremities had pitting edema with superficial erosions that were weeping serous fluid. She was afebrile and normotensive, but had shaking chills and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 bpm. There was no nail pitting, pustules, or lymphadenopathy. Lab tests revealed a low albumin level of 2.2 g/dL (normal: 3.5-5.5 g/dL), an elevated white blood cell count of 14,700 cells/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000 cells/mcL), and normocytic anemia (low hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL; normal: 12-15.5 g/dL). The patient was admitted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythroderma

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed severe erythroderma secondary to psoriasis. A punch biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated subacute spongiotic dermatitis with superficial neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with psoriasis.

Erythroderma is widespread reddening of the skin associated with desquamation, typically involving more than 90% of the body’s surface area.1 In most instances, erythroderma is a clinical presentation of an existing dermatosis. The most common causative conditions include primary skin disorders (such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis), idiopathic erythroderma, and drug eruptions. Less common causes include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and contact dermatitis.1

It’s unclear why some skin diseases progress to erythroderma; the pathogenesis is complicated and involves keratinocytes and lymphocytes interacting with adhesion molecules and cytokines. Erythroderma can arise at any age and occurs in all races, but is more common in males and older adults, with a mean age of 42 to 61 years.2 The annual incidence of erythroderma is estimated to be one per 100,000 adults.3

A complete picture of the patient is essential to making the diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult and hinges on historical and physical exam findings, as well as lab evaluations and skin biopsies. The history should focus on current and former medications, while the physical exam should hone in on clinical manifestations of existing dermatoses. The most common extracutaneous finding is generalized lymphadenopathy, which if prominent, may warrant lymph node biopsy, with studies for evaluation of underlying lymphoma.

Tachycardia develops in 40% of patients, secondary to increased blood flow to the skin and fluid loss, with risk of high-output cardiac failure.2 Patients often have chills because their skin is not able to regulate their body temperature normally.4

The lab evaluation should include a complete blood count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic panel, as well as blood, skin, and urine cultures if infection is suspected as an inciting factor. Typical findings include mild anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 In addition, patients with chronic erythroderma commonly have low albumin.6 Unfortunately, lab studies don’t always reveal the underlying cause of the erythroderma.

Biopsies are commonly performed. However, the underlying etiology is often not clearly reflected in the result. Histology is typically nonspecific; findings frequently include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Additionally, the prominence of histologic features may vary depending on the stage of disease and the severity of inflammation. More specific findings may become evident later in the disease as the erythroderma clears, so repeated skin biopsies over time may be needed for diagnosis.7

Consider these conditions, which can lead to erythroderma

First and foremost, it is important to get a thorough history, particularly about prior skin conditions and symptoms that may indicate the presence of undiagnosed skin conditions.

Psoriasis is one of the most common causes of erythroderma. A history of pre-existing psoriasis is very helpful, but when this is not present, a biopsy can help confirm a clinical suspicion for psoriasis. It also helps to look for clues of psoriasis like nail changes or a history of plaques over the elbows and knees.

Atopic dermatitis is another common cause of erythroderma, and the history might include scaling and erythematous patches or plaques involving flexural surfaces before erythroderma occurs. Patients may have a history of atopic dermatitis from childhood and/or a history of other atopic conditions such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Drug eruptions occur following the administration of a new medication and can mimic a myriad of dermatoses.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can lead to erythroderma and be differentiated with skin biopsy; pathology may show atypical lymphocytes, and Pautrier’s microabscesses may be seen.8

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a relatively rare condition that presents with red-orange scaling patches and thickened yellowish palms and soles.9

Tx targets underlying etiology and associated complications

When treating a patient with erythroderma, it’s important to prevent hypothermia and secondary infections. If symptoms are severe, hospitalization should be considered. Nutrition should be assessed, and any fluid or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected.

Oral antihistamines are commonly administered to suppress associated pruritus. Topical treatment usually consists of corticosteroids under occlusion with bland emollients. Depending upon the underlying disease, the following systemic medications may be started: methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg once/week; acitretin 10 to 25 mg/d; or cyclosporine 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/d; in addition to topical treatment.4

Our patient. Pathology for our patient was indicative of psoriasis. She was started on a regimen of cyclosporine 4 to 5 mg/kg/d, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg as needed for itching, triamcinolone 0.1% ointment under wet wraps to her trunk and extremities, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment to be applied to her face daily. She was released after 5 days in the hospital. At outpatient follow-up one week later, her erythroderma was resolving. One month later, her erythroderma was resolved (FIGURE 2), although she did have psoriatic plaques on her lower legs.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; Usatine@uthscsa.edu.

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of diffuse redness, itching, and tenderness of her skin. The patient said the eruption began 4 months earlier as localized plaques on her scalp, elbows, and beneath both breasts. Over the course of a few days, the redness became more diffuse, affecting most of her body. She also noticed swelling and skin desquamation on her lower extremities.

The patient had visited multiple urgent care clinics and underwent several courses of prednisone with initial improvement of symptoms, but experienced recurrence shortly after finishing the tapers.

On physical examination, more than 95% of the patient’s skin was bright red and tender to the touch, with associated exfoliation (FIGURES 1A-1B). Her lower extremities had pitting edema with superficial erosions that were weeping serous fluid. She was afebrile and normotensive, but had shaking chills and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 bpm. There was no nail pitting, pustules, or lymphadenopathy. Lab tests revealed a low albumin level of 2.2 g/dL (normal: 3.5-5.5 g/dL), an elevated white blood cell count of 14,700 cells/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000 cells/mcL), and normocytic anemia (low hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL; normal: 12-15.5 g/dL). The patient was admitted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythroderma

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed severe erythroderma secondary to psoriasis. A punch biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated subacute spongiotic dermatitis with superficial neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with psoriasis.

Erythroderma is widespread reddening of the skin associated with desquamation, typically involving more than 90% of the body’s surface area.1 In most instances, erythroderma is a clinical presentation of an existing dermatosis. The most common causative conditions include primary skin disorders (such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis), idiopathic erythroderma, and drug eruptions. Less common causes include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and contact dermatitis.1

It’s unclear why some skin diseases progress to erythroderma; the pathogenesis is complicated and involves keratinocytes and lymphocytes interacting with adhesion molecules and cytokines. Erythroderma can arise at any age and occurs in all races, but is more common in males and older adults, with a mean age of 42 to 61 years.2 The annual incidence of erythroderma is estimated to be one per 100,000 adults.3

A complete picture of the patient is essential to making the diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult and hinges on historical and physical exam findings, as well as lab evaluations and skin biopsies. The history should focus on current and former medications, while the physical exam should hone in on clinical manifestations of existing dermatoses. The most common extracutaneous finding is generalized lymphadenopathy, which if prominent, may warrant lymph node biopsy, with studies for evaluation of underlying lymphoma.

Tachycardia develops in 40% of patients, secondary to increased blood flow to the skin and fluid loss, with risk of high-output cardiac failure.2 Patients often have chills because their skin is not able to regulate their body temperature normally.4

The lab evaluation should include a complete blood count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic panel, as well as blood, skin, and urine cultures if infection is suspected as an inciting factor. Typical findings include mild anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 In addition, patients with chronic erythroderma commonly have low albumin.6 Unfortunately, lab studies don’t always reveal the underlying cause of the erythroderma.

Biopsies are commonly performed. However, the underlying etiology is often not clearly reflected in the result. Histology is typically nonspecific; findings frequently include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Additionally, the prominence of histologic features may vary depending on the stage of disease and the severity of inflammation. More specific findings may become evident later in the disease as the erythroderma clears, so repeated skin biopsies over time may be needed for diagnosis.7

Consider these conditions, which can lead to erythroderma

First and foremost, it is important to get a thorough history, particularly about prior skin conditions and symptoms that may indicate the presence of undiagnosed skin conditions.

Psoriasis is one of the most common causes of erythroderma. A history of pre-existing psoriasis is very helpful, but when this is not present, a biopsy can help confirm a clinical suspicion for psoriasis. It also helps to look for clues of psoriasis like nail changes or a history of plaques over the elbows and knees.

Atopic dermatitis is another common cause of erythroderma, and the history might include scaling and erythematous patches or plaques involving flexural surfaces before erythroderma occurs. Patients may have a history of atopic dermatitis from childhood and/or a history of other atopic conditions such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Drug eruptions occur following the administration of a new medication and can mimic a myriad of dermatoses.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can lead to erythroderma and be differentiated with skin biopsy; pathology may show atypical lymphocytes, and Pautrier’s microabscesses may be seen.8

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a relatively rare condition that presents with red-orange scaling patches and thickened yellowish palms and soles.9

Tx targets underlying etiology and associated complications

When treating a patient with erythroderma, it’s important to prevent hypothermia and secondary infections. If symptoms are severe, hospitalization should be considered. Nutrition should be assessed, and any fluid or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected.

Oral antihistamines are commonly administered to suppress associated pruritus. Topical treatment usually consists of corticosteroids under occlusion with bland emollients. Depending upon the underlying disease, the following systemic medications may be started: methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg once/week; acitretin 10 to 25 mg/d; or cyclosporine 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/d; in addition to topical treatment.4

Our patient. Pathology for our patient was indicative of psoriasis. She was started on a regimen of cyclosporine 4 to 5 mg/kg/d, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg as needed for itching, triamcinolone 0.1% ointment under wet wraps to her trunk and extremities, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment to be applied to her face daily. She was released after 5 days in the hospital. At outpatient follow-up one week later, her erythroderma was resolving. One month later, her erythroderma was resolved (FIGURE 2), although she did have psoriatic plaques on her lower legs.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; Usatine@uthscsa.edu.

1. Keisham C, Sahoo B, Khurana N, et al. Clinicopathologic study of erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB85.

2. Li J, Zheng H-Y. Erythroderma: a clinical and prognostic study. Dermatology. 2012;225:154-162.

3. Sigurdsson V, Steegmans PH, van Vioten WA. The incidence of erythroderma: a survey among all dermatologists in The Netherlands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:675-678.

4. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology essentials. 1st ed. Oxford, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

5. Karakayli G, Beckham G, Orengo I, et al. Exfoliative dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:625-630.

6. Rothe MJ, Bialy TL, Grant-Kels JM. Erythroderma. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:405-415.

7. Walsh NM, Prokopetz R, Tron VA, et al. Histopathology in erythroderma: review of a series of cases by multiple observers. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:419-423.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

9. Abdel-Azim NE, Ismail SA, Fathy E. Differentiation of pityriasis rubra pilaris from plaque psoriasis by dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:311-314.

1. Keisham C, Sahoo B, Khurana N, et al. Clinicopathologic study of erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB85.

2. Li J, Zheng H-Y. Erythroderma: a clinical and prognostic study. Dermatology. 2012;225:154-162.

3. Sigurdsson V, Steegmans PH, van Vioten WA. The incidence of erythroderma: a survey among all dermatologists in The Netherlands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:675-678.

4. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology essentials. 1st ed. Oxford, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

5. Karakayli G, Beckham G, Orengo I, et al. Exfoliative dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:625-630.

6. Rothe MJ, Bialy TL, Grant-Kels JM. Erythroderma. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:405-415.

7. Walsh NM, Prokopetz R, Tron VA, et al. Histopathology in erythroderma: review of a series of cases by multiple observers. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:419-423.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

9. Abdel-Azim NE, Ismail SA, Fathy E. Differentiation of pityriasis rubra pilaris from plaque psoriasis by dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:311-314.