User login

Irritated Pigmented Plaque on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

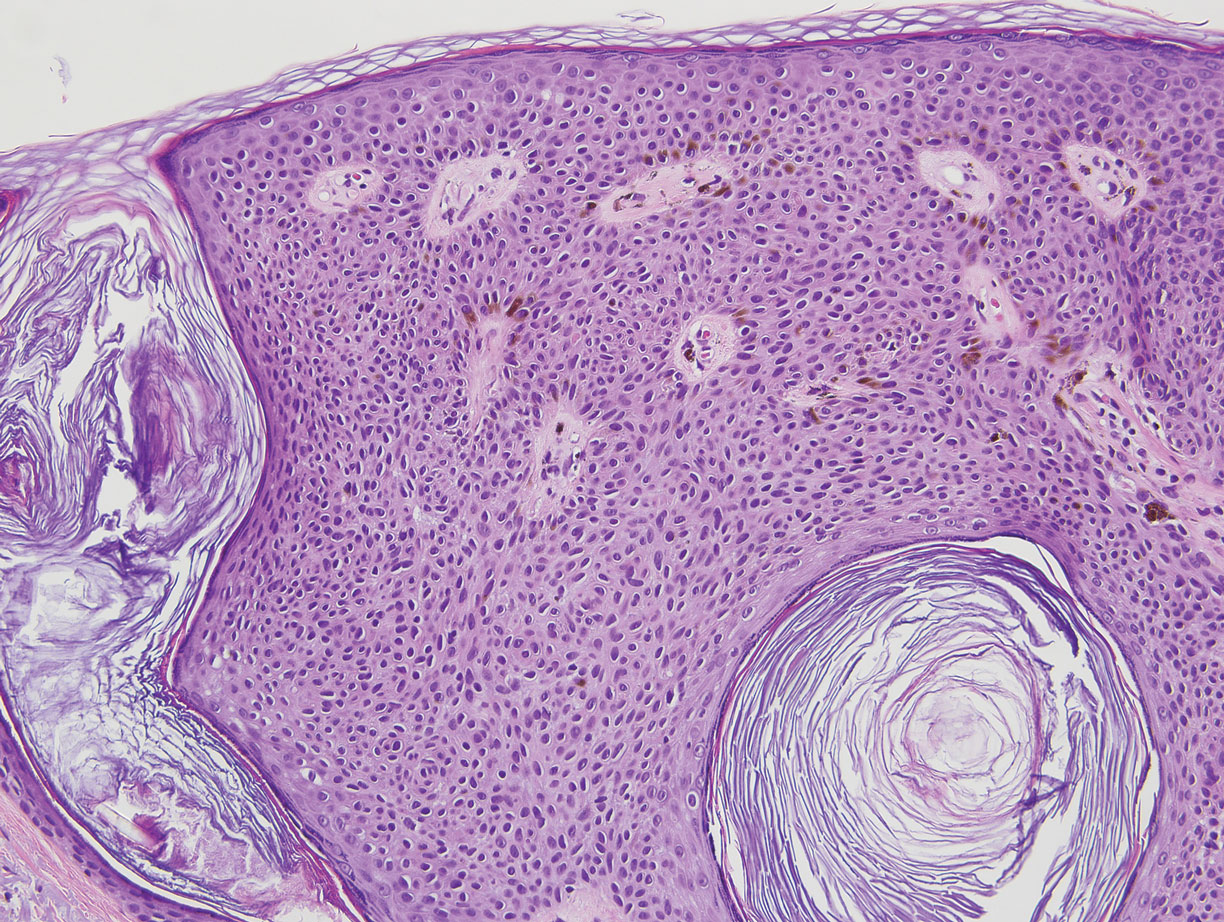

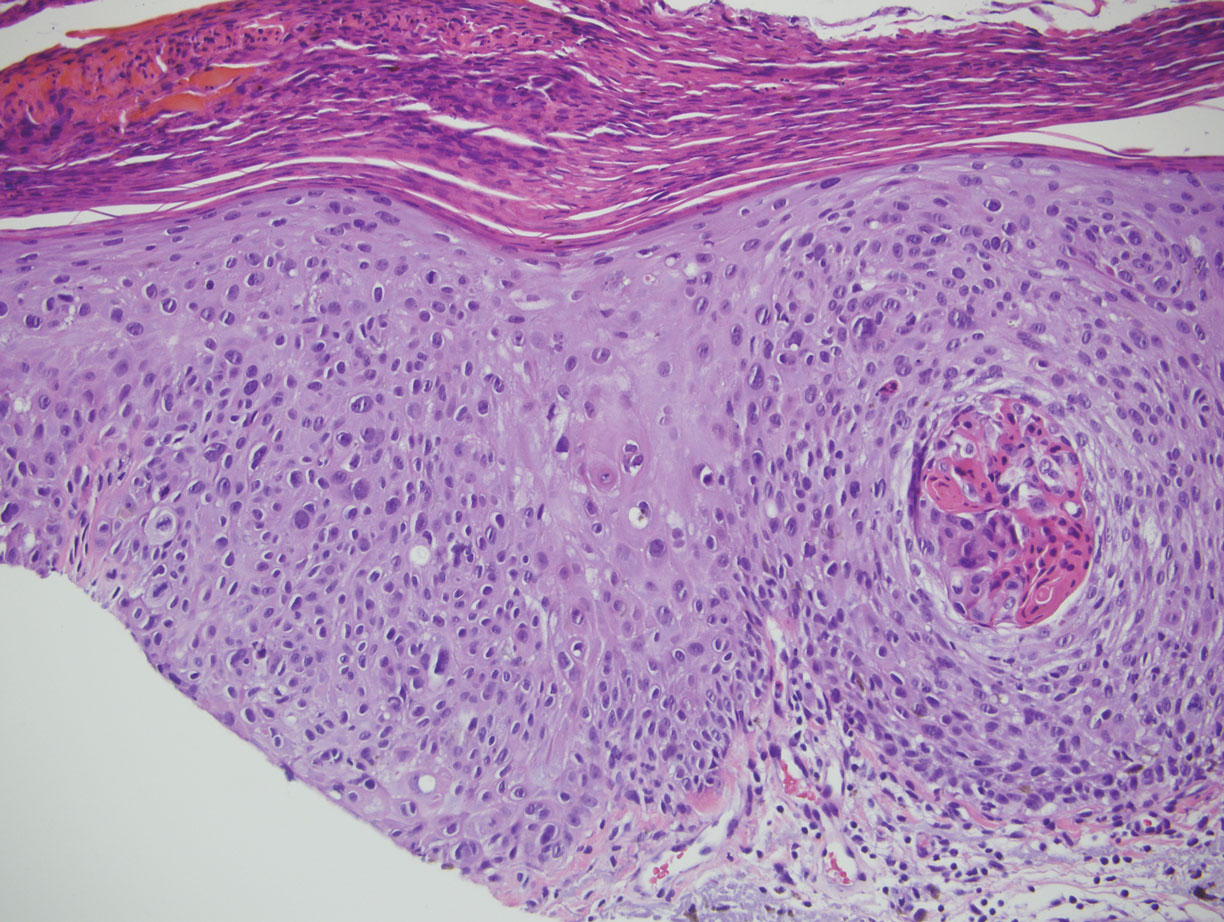

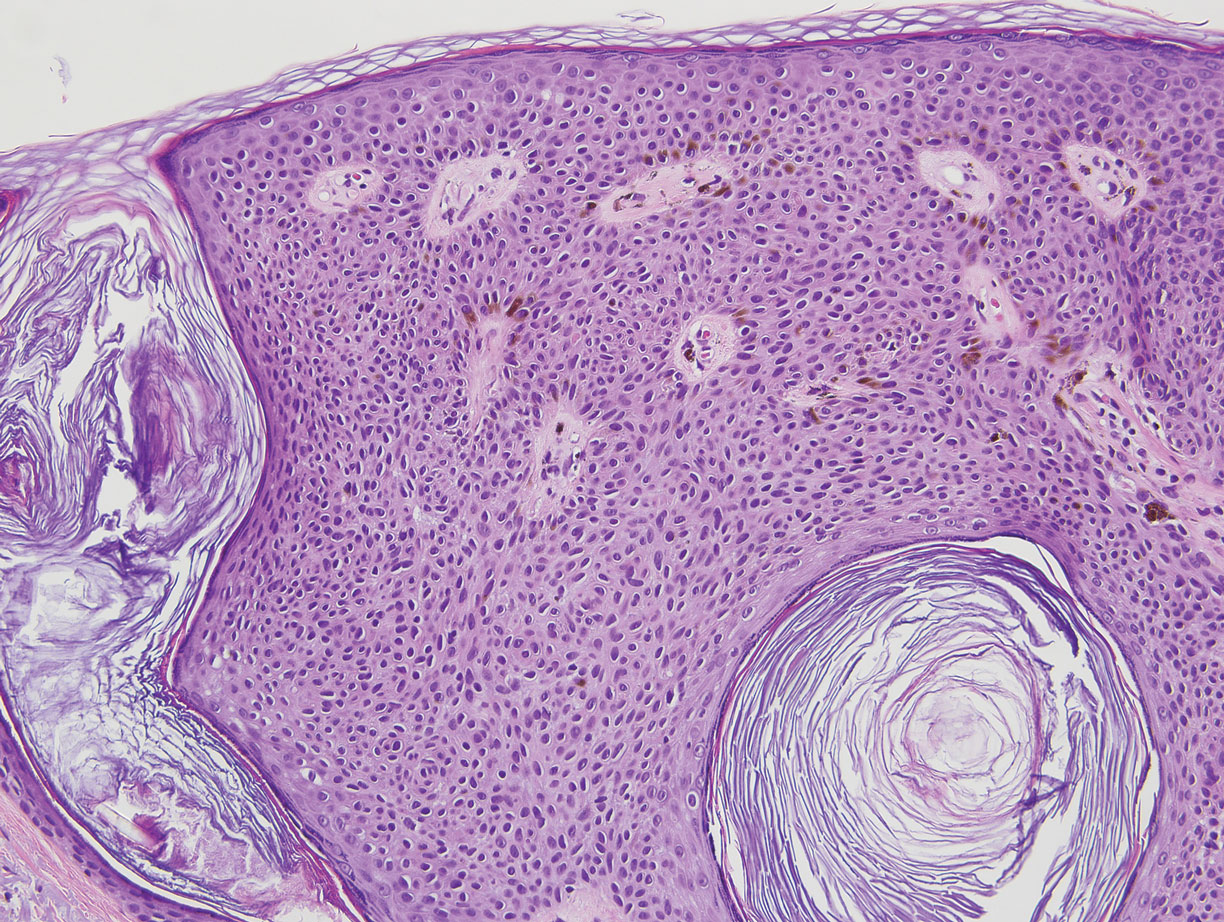

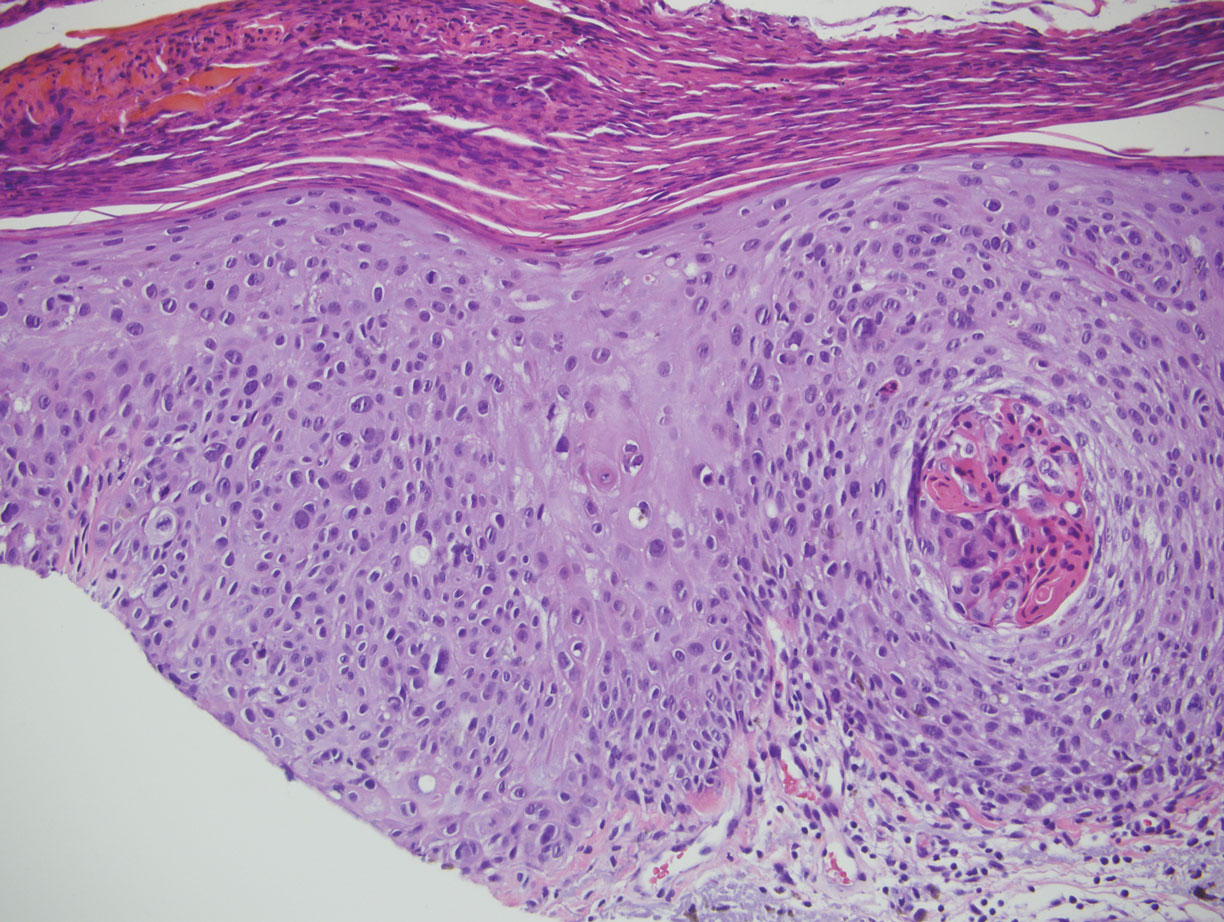

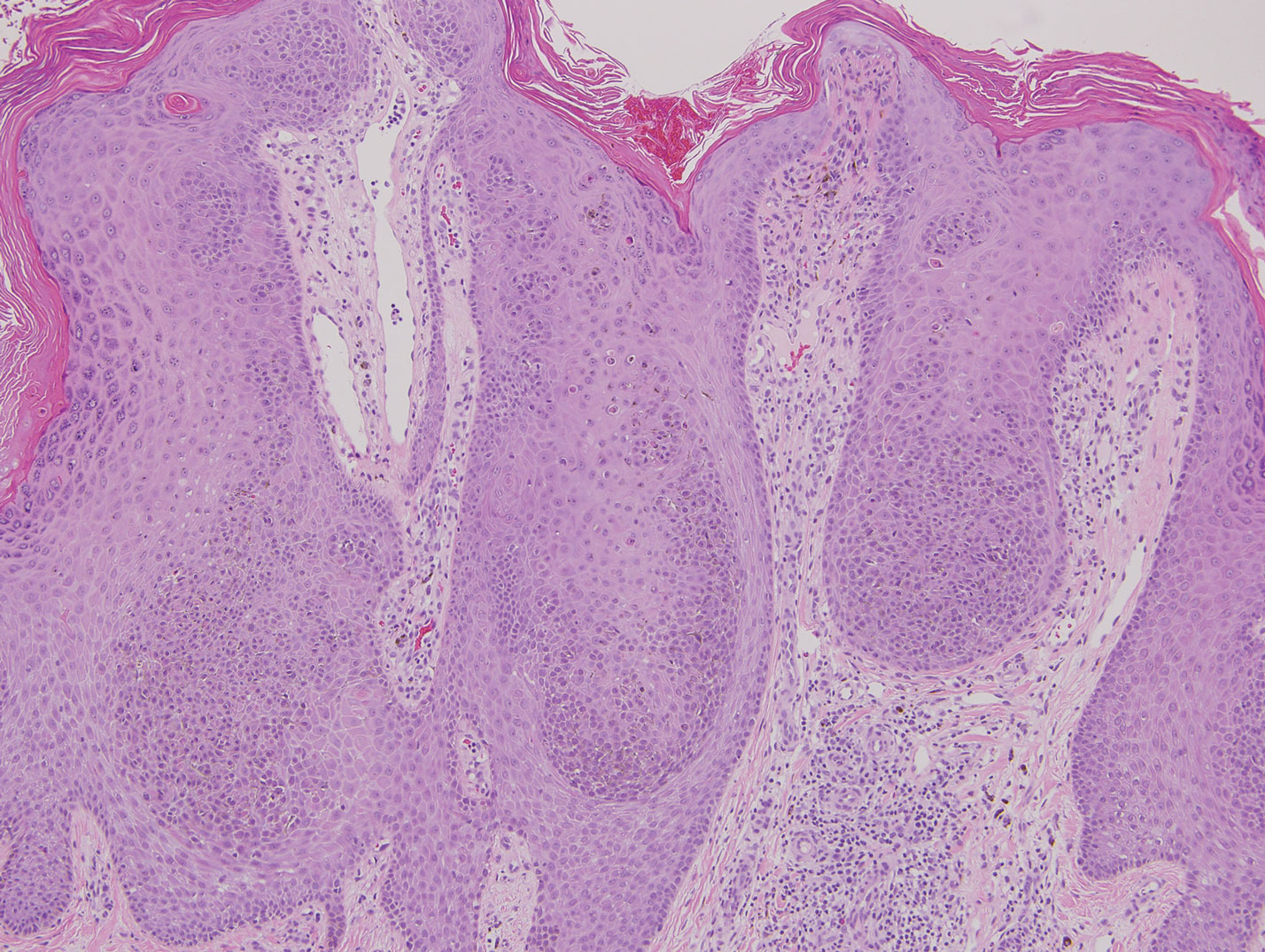

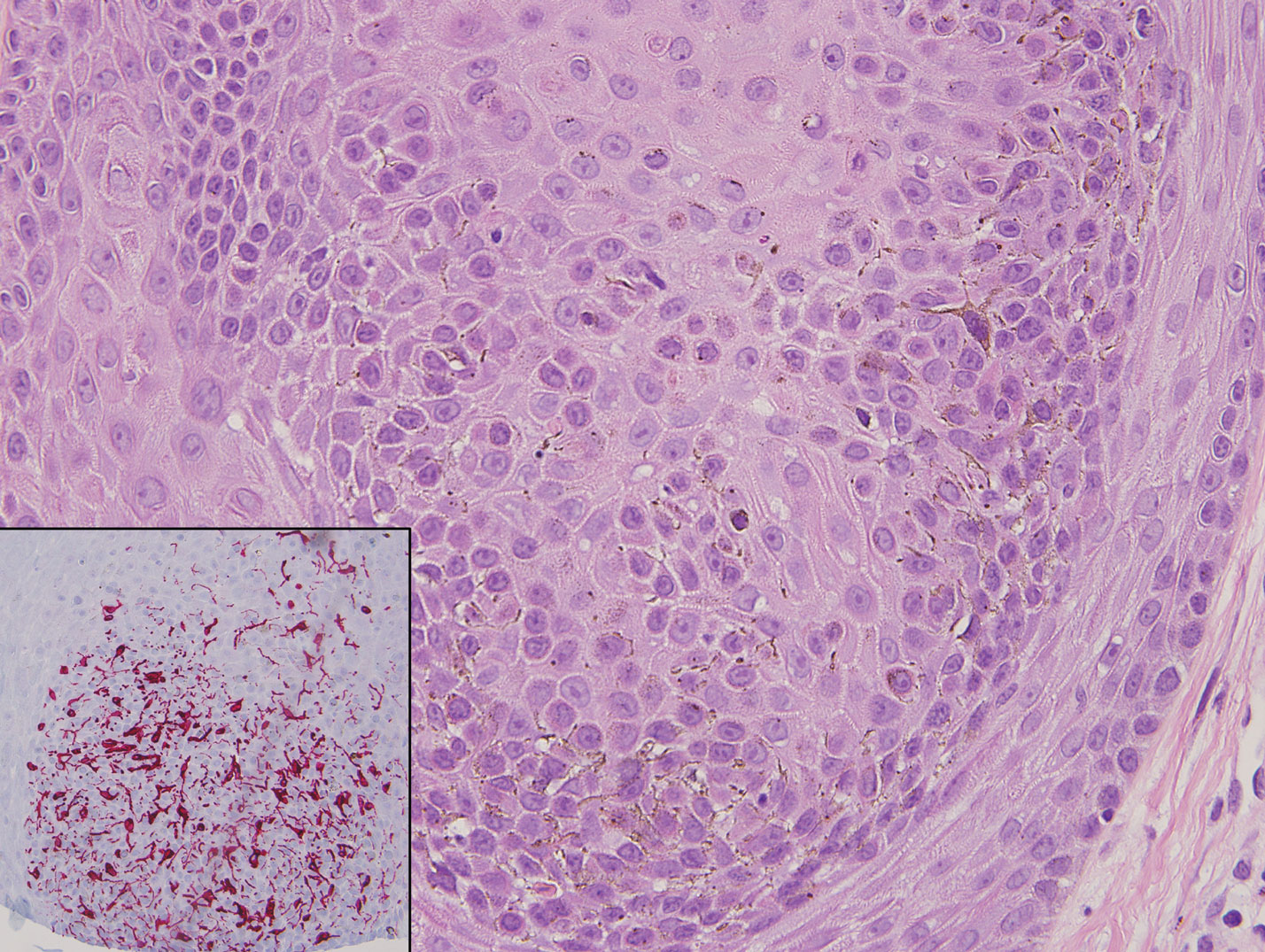

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

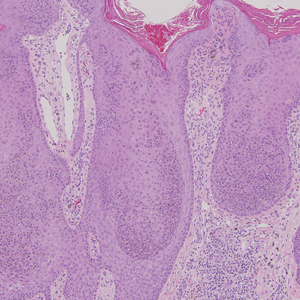

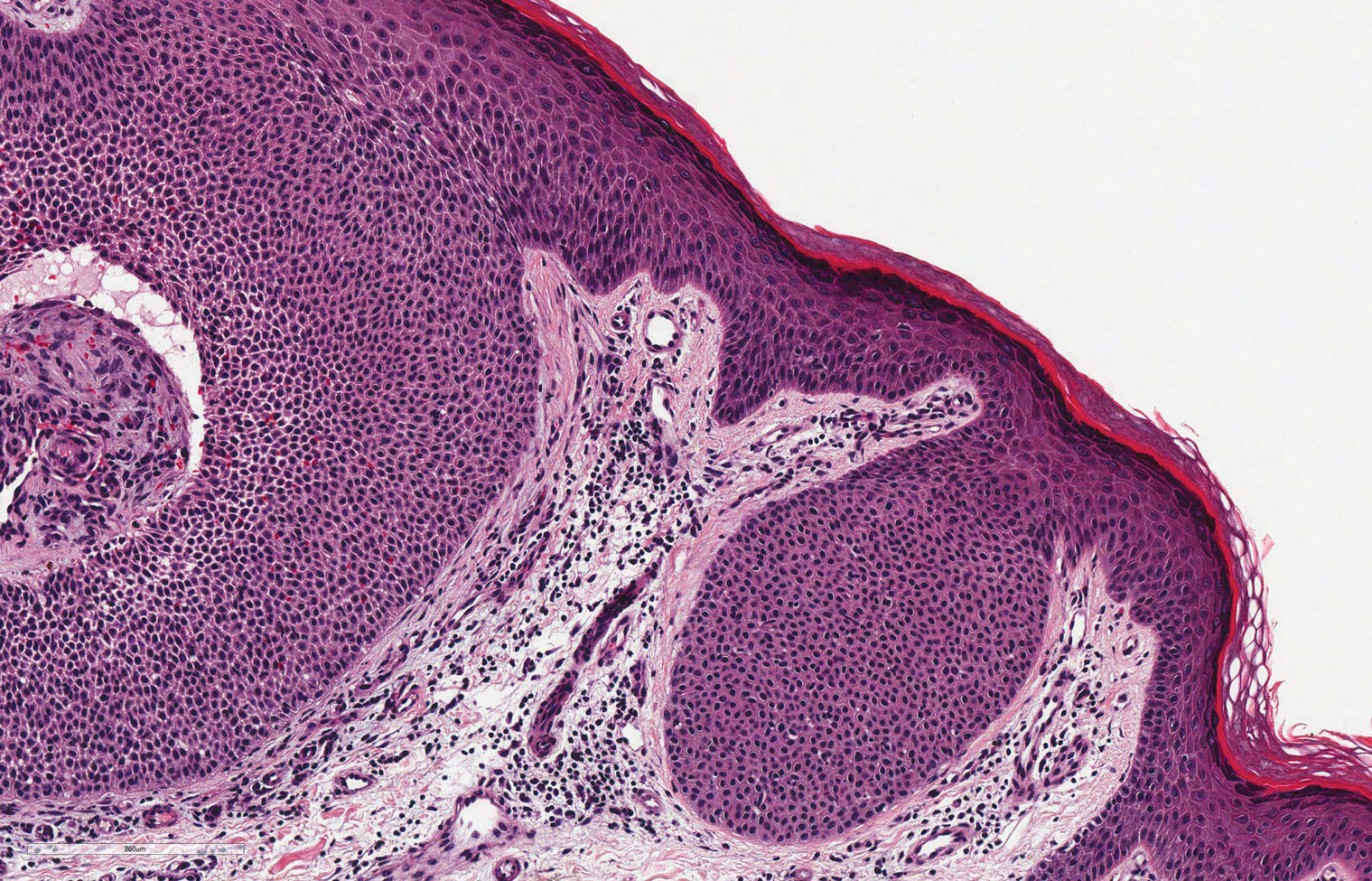

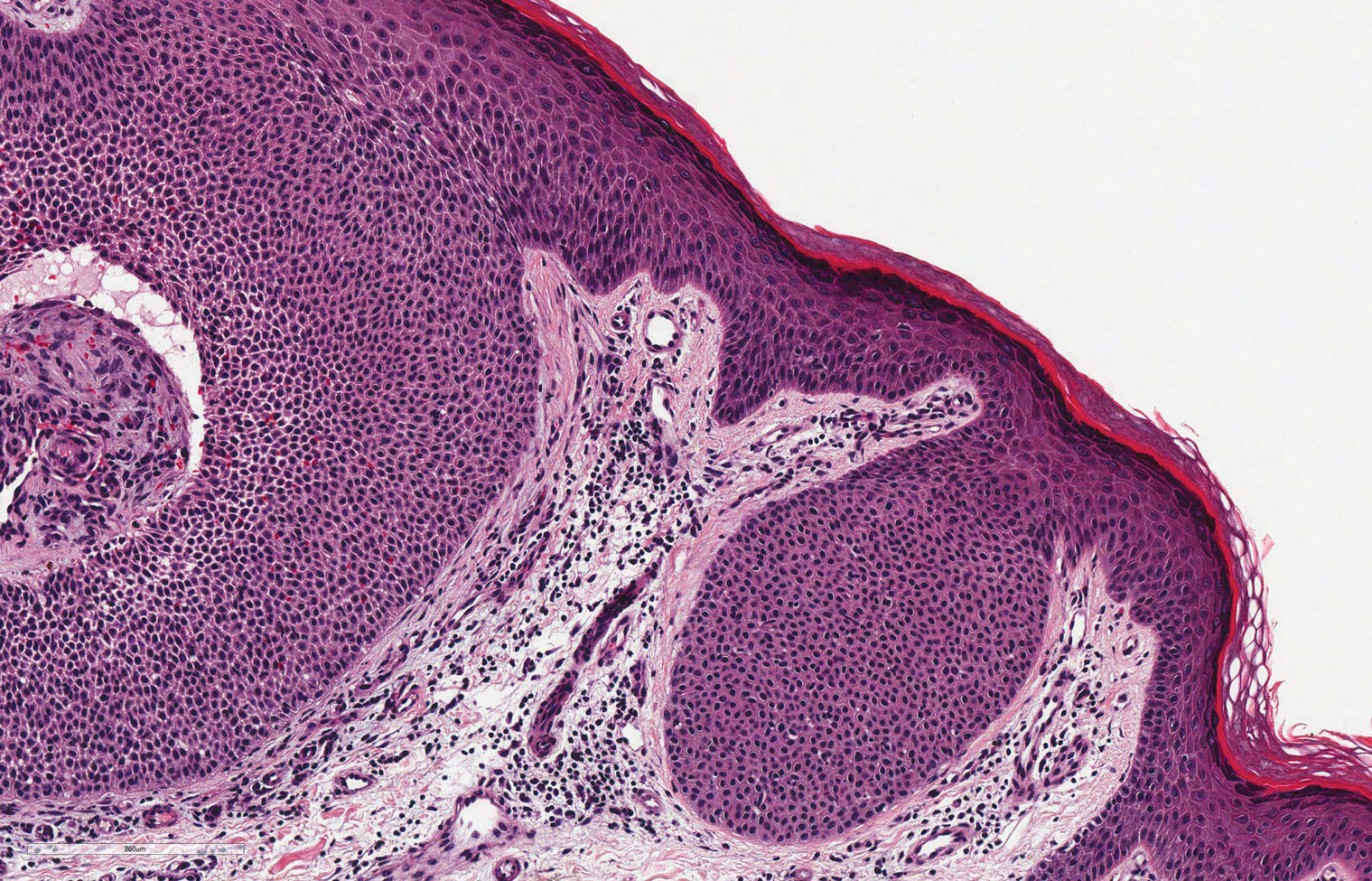

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

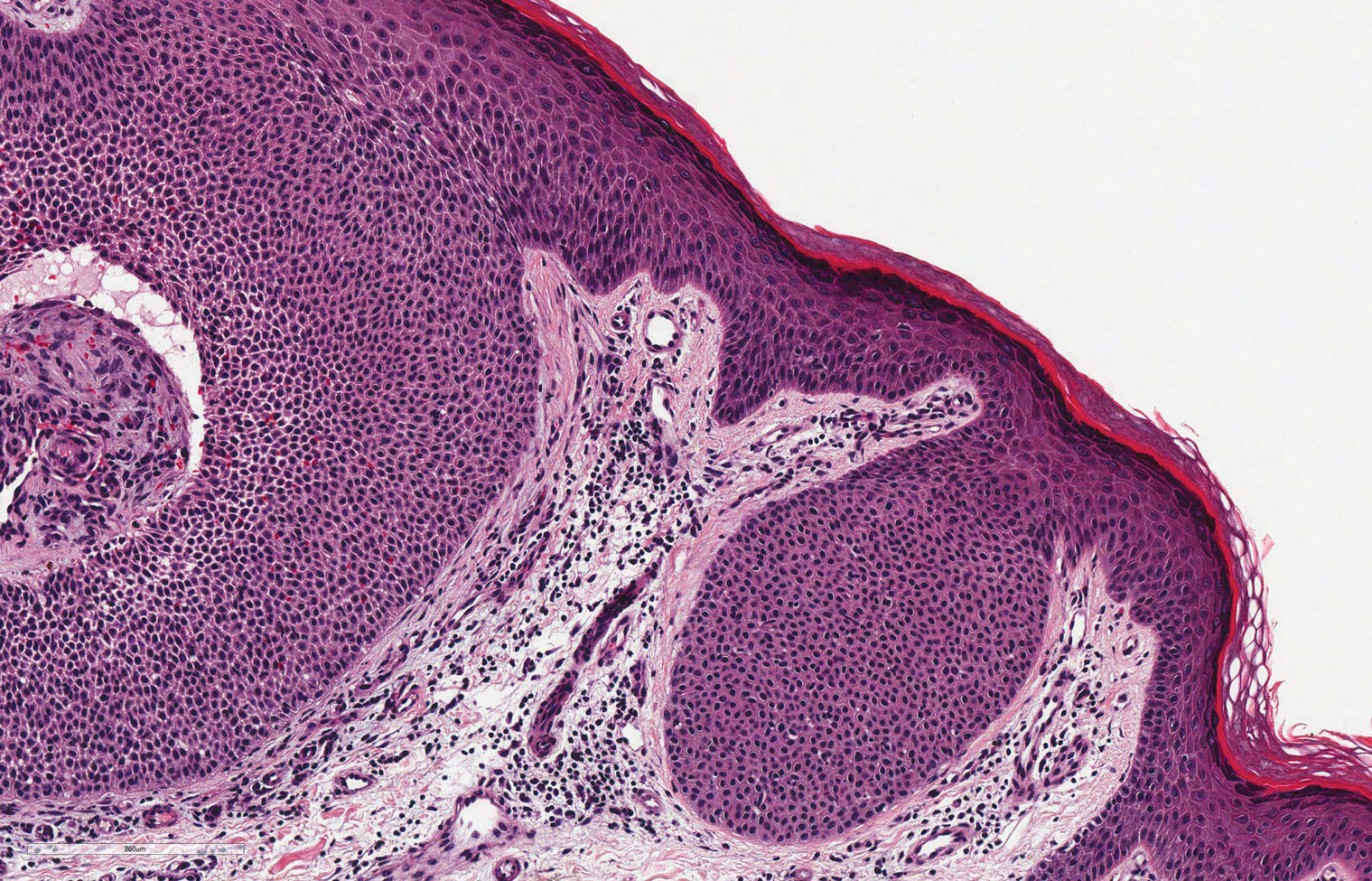

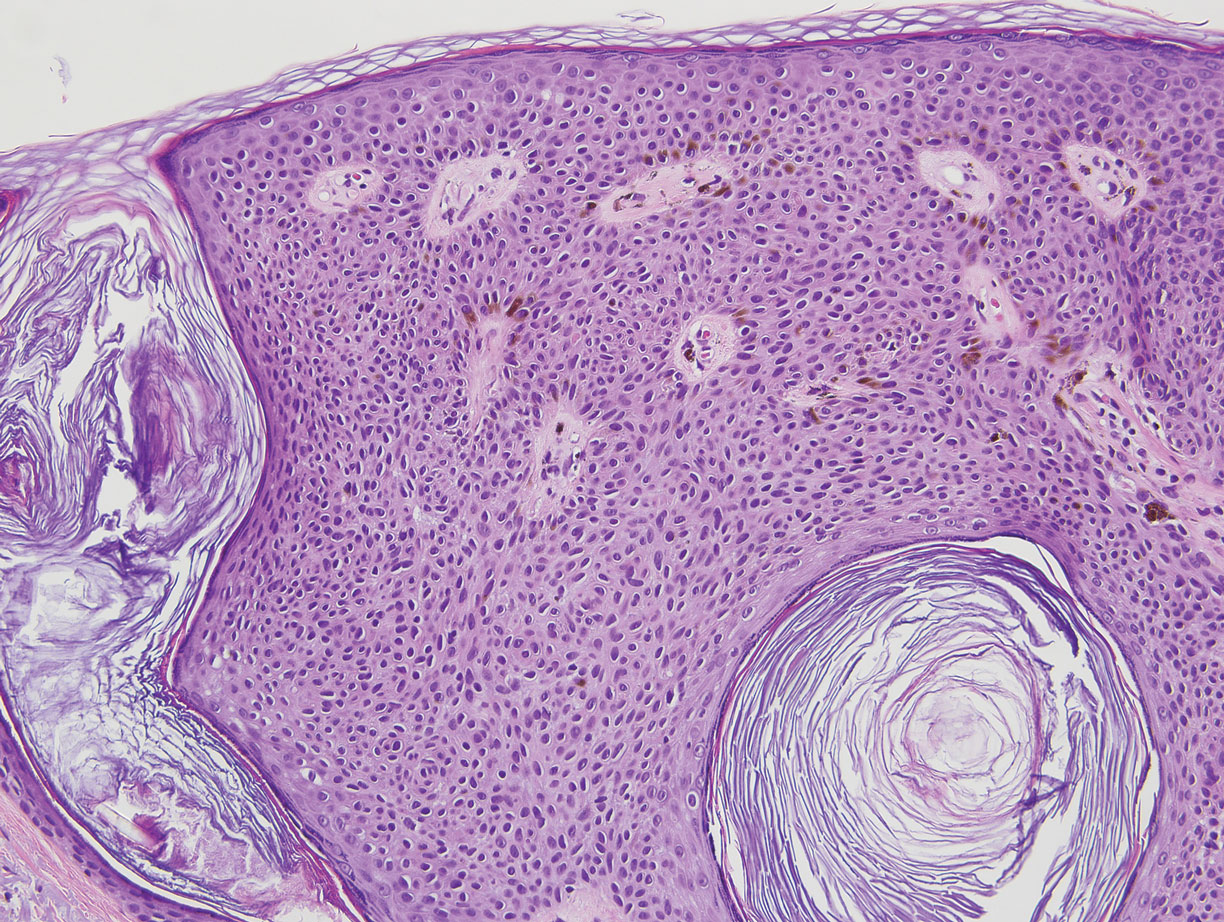

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

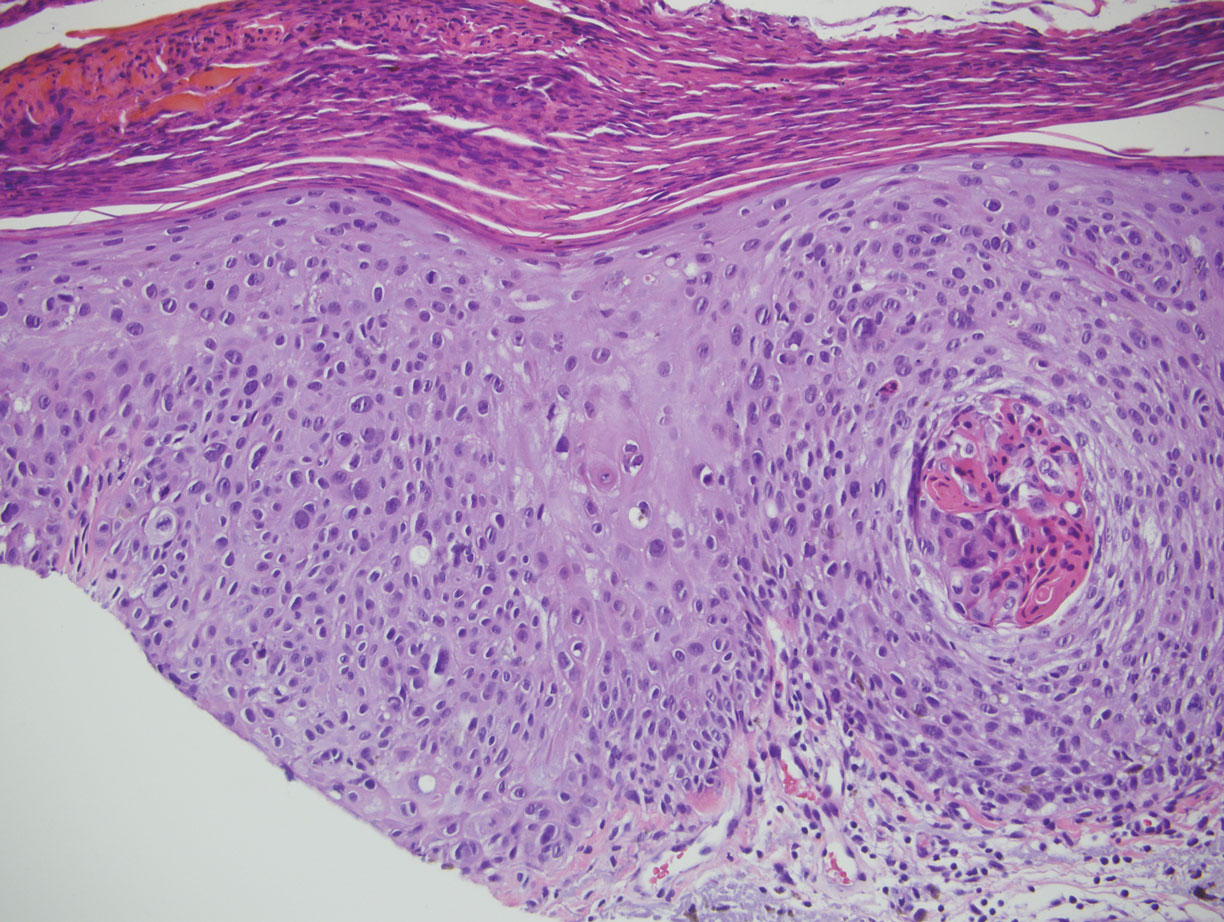

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

A 49-year-old man with light brown skin and no history of skin cancer presented with a pruritic lesion on the scalp of 3 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 7×3-cm, brown, mammillated plaque on the left parietal scalp. A shave biopsy of the scalp lesion was performed.

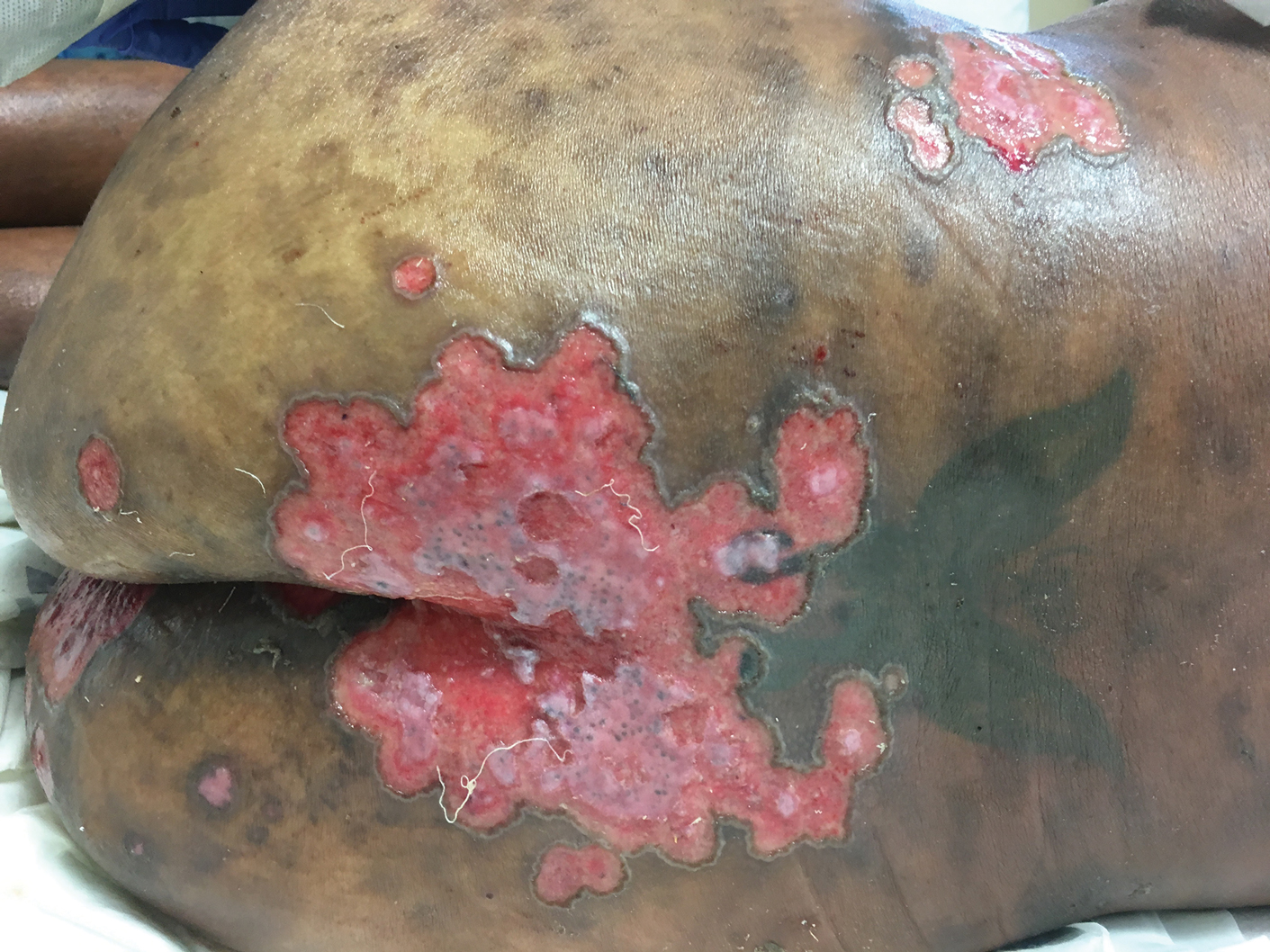

Pink Polycyclic Ulcerations on the Lower Back and Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

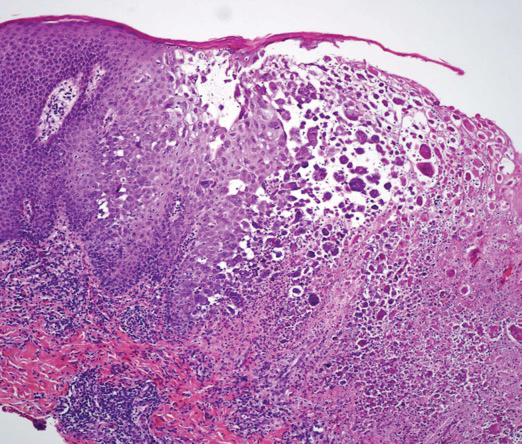

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Virus

A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and was negative for mycobacterial, bacterial, and fungal growth. Histopathologic examination showed ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with herpetic cytopathic effect consistent with herpetic ulceration (Figure). A swab of the lesion on the buttock was sent for human herpesvirus (HHV) and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acid testing, which was positive for HHV-2. She was started on oral valacyclovir 1000 mg twice daily for 10 days and then was continued on chronic suppression with 500 mg once daily. The patient's ulcerations healed slowly over the following few weeks.

Human herpesvirus 2 is the most common cause of genital ulcer disease and may present as chronic and recurrent ulcers in immunocompromised patients.1 It usually is spread by sexual contact. Primary infection typically occurs in the cells of the dermis and epidermis. Two weeks after the primary infection, extragenital lesions can occur in the lumbosacral area on the buttocks, fingers, groin, or thighs, as seen in our patient,2 which is a direct result of viral shedding and spread. Reactivation of HHV from the ganglia can occur with or without symptoms. Common locations for viral shedding in women are the cervix, vulva, and perianal areas.3 Patients should be counseled to avoid sexual contact during recurrences.

Cancer patients have a particularly increased risk for developing HHV-2 due to their limited cell-mediated immunity and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.4 Moreover, approximately 5% of immunocompromised patients develop resistance to antiviral therapy.5 Although this phenomenon was not observed in our patient, identification of novel strategies to treat these new groups of patients will be essential.

The differential diagnosis includes perianal candidiasis, which is classified by erythematous plaques with satellite vesicles and pustules. Contact dermatitis is common in the buttock area and usually secondary to ingredients in cleansing wipes and topical treatments. It is defined by a well-demarcated, symmetric rash, which is more eczematous in nature. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was high in our differential given the patient's history of the disease. There are many variants, and tumor-stage disease may result in ulceration of the skin. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is differentiated by histology with immunophenotyping in conjunction with the clinical picture. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may cause genital ulcerations, which can be diagnosed with a positive EBV serology and detection of EBV by a polymerase chain reaction swab of the ulceration.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

- Schiffer JT, Corey L. New concepts in understanding genital herpes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2009;11:457-464.

- Vassantachart JM, Menter A. Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29:48-49.

- Tata S, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Overlapping reactivations of HSV-2 in the genital and perianal mucosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:499-504.

- Tang IT, Shepp DH. Herpes simplex virus infection in cancer patients: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 1992;6:101-106.

- Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, et al. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:1-6.

A 32-year-old woman with stage IV cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was admitted with pancytopenia and septic shock secondary to methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Dermatology was consulted regarding sacral ulcerations. The lesions were asymptomatic and had been slowly enlarging over the course of 1 month. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, pink, polycyclic ulcerations on the lower back and buttocks extending onto the perineum. There was no pain or tingling associated with the ulcerations. She denied a history of cold sore lesions on the lips or genitals. A skin biopsy was sent for tissue culture and histopathologic examination.