User login

Irritated Pigmented Plaque on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

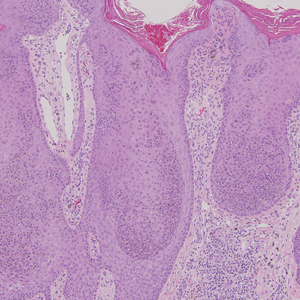

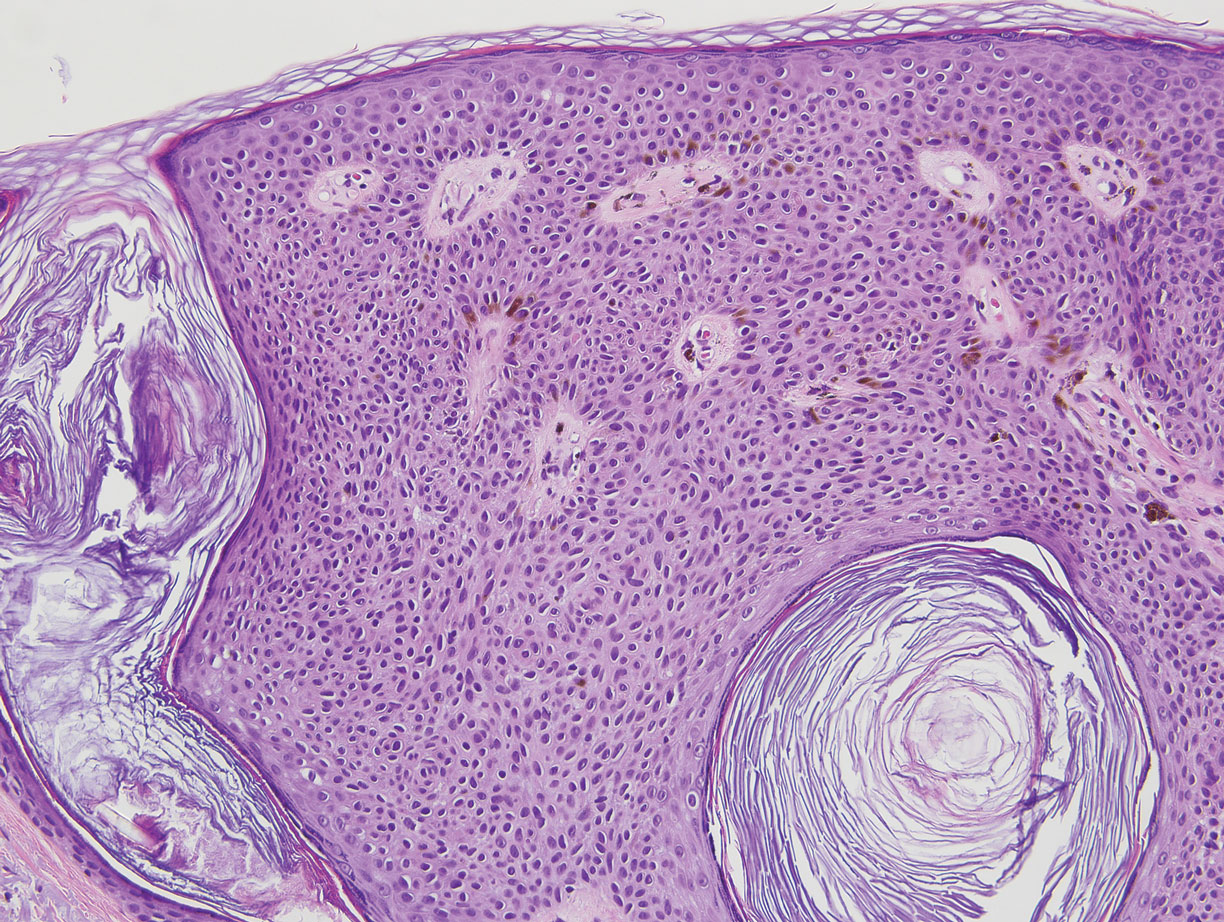

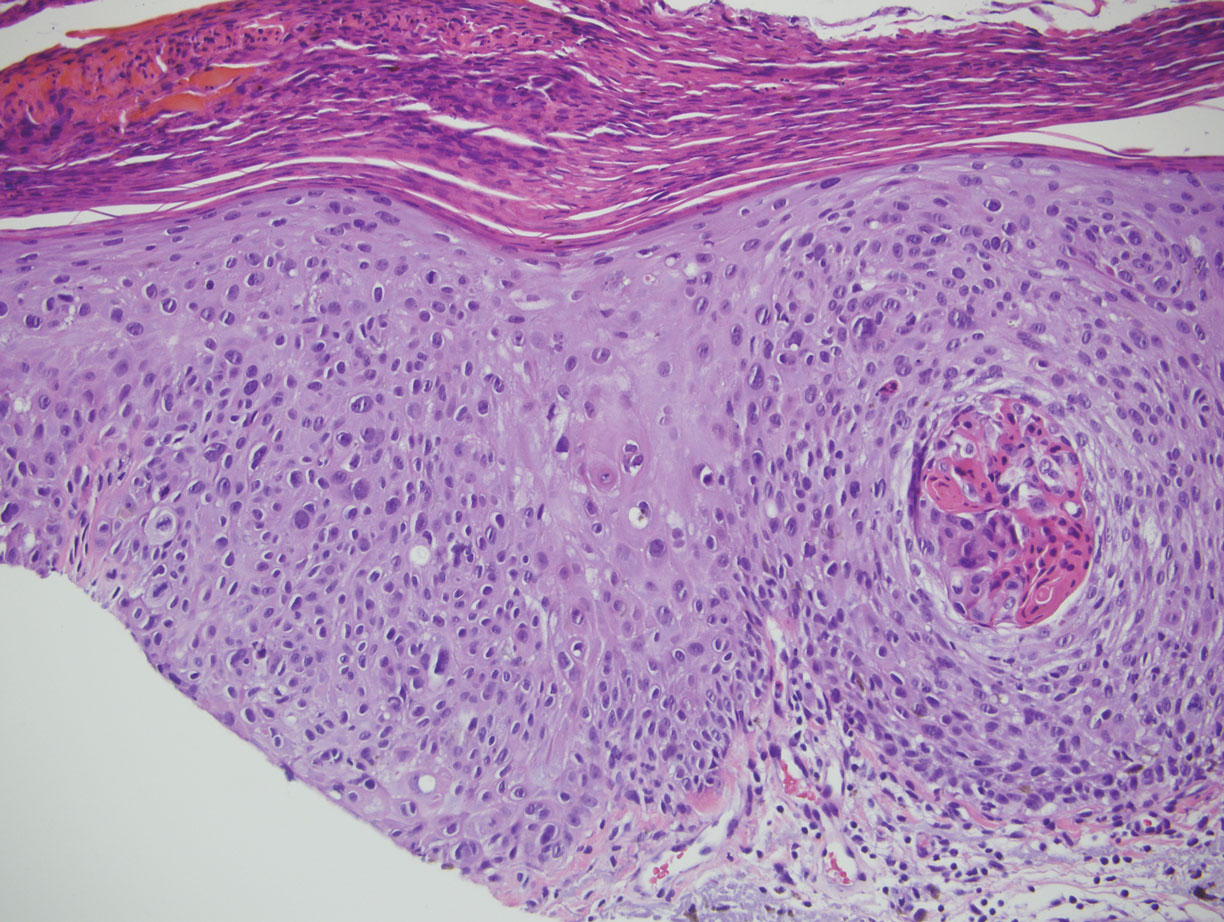

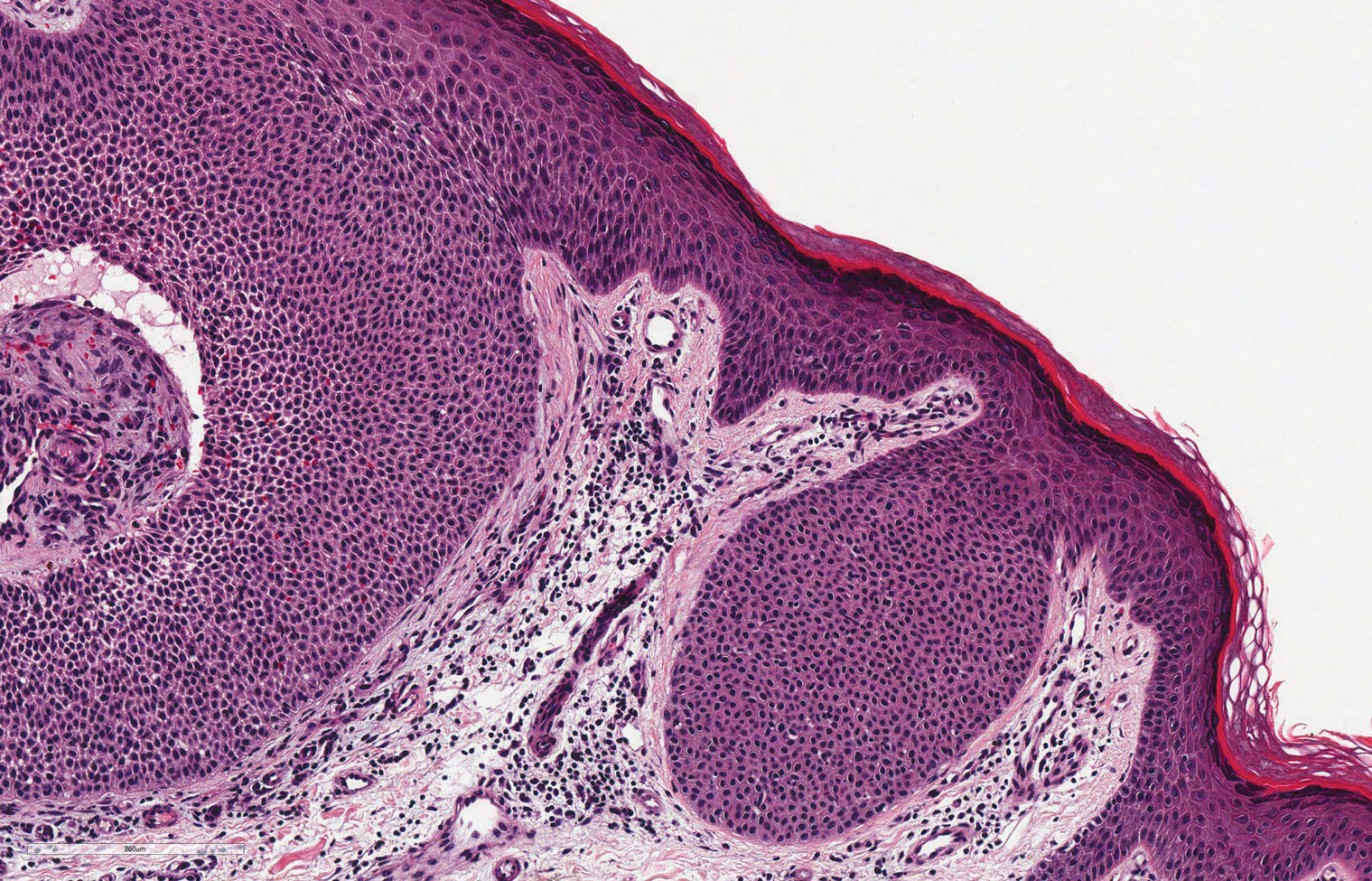

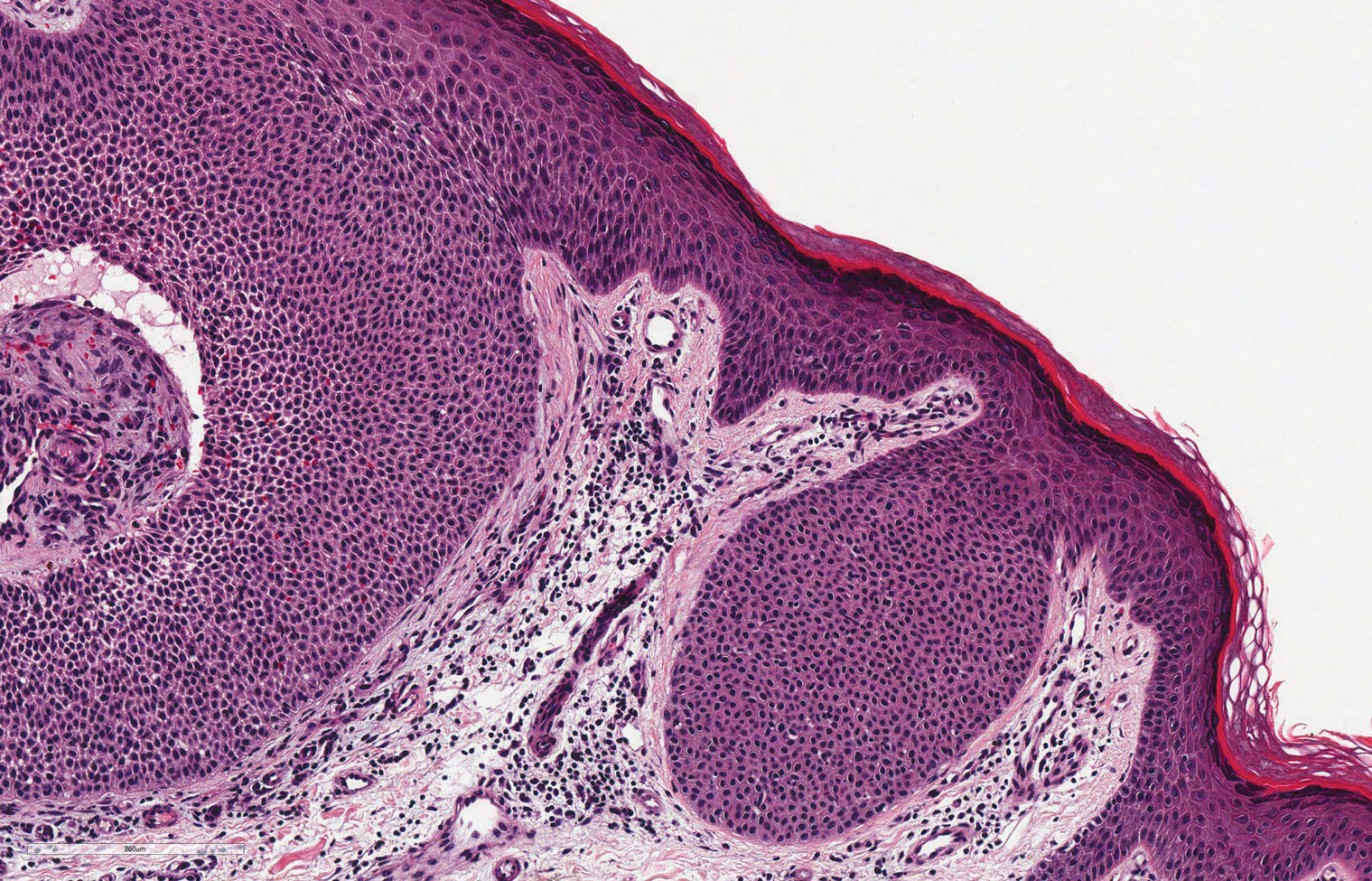

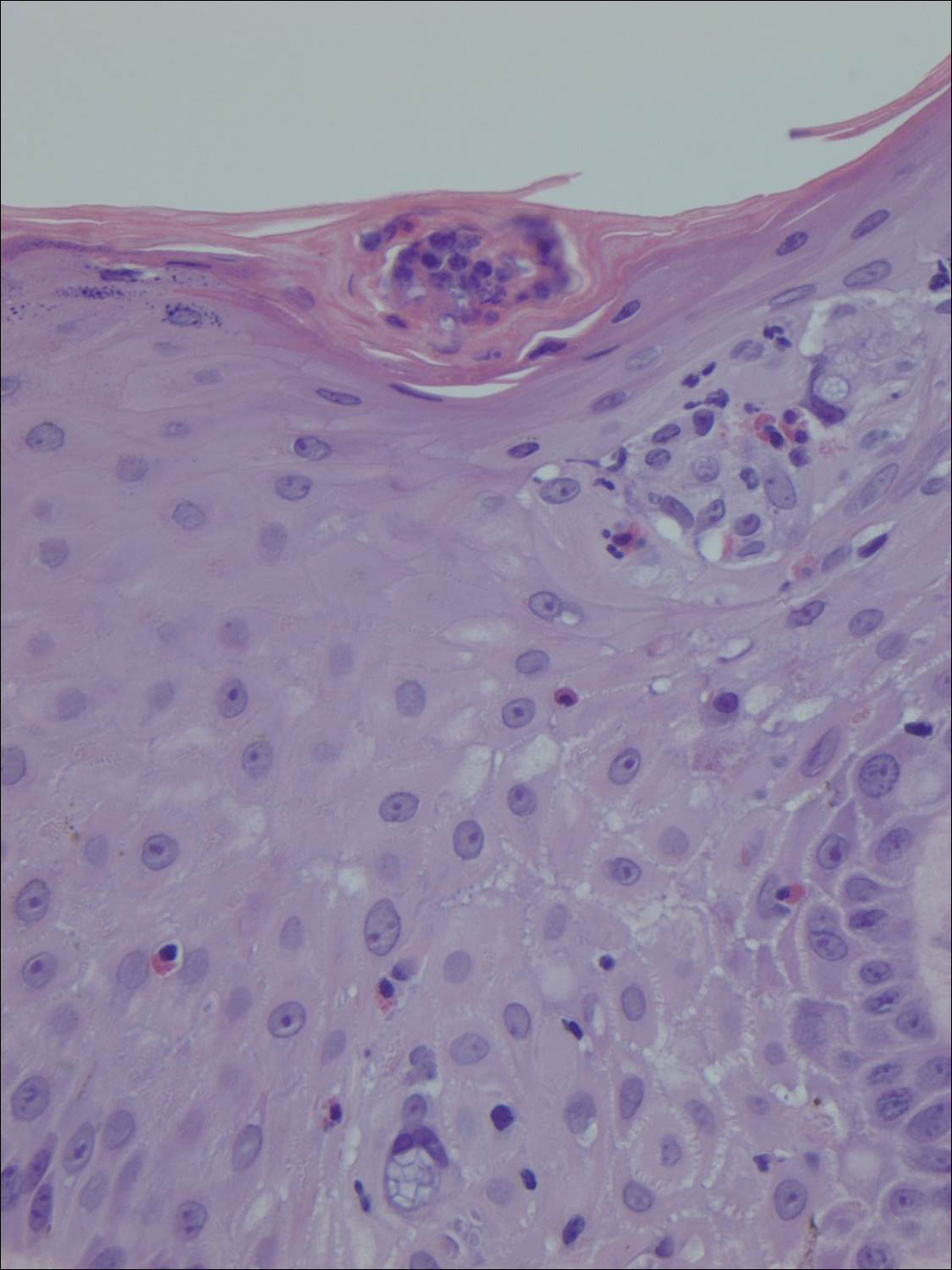

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

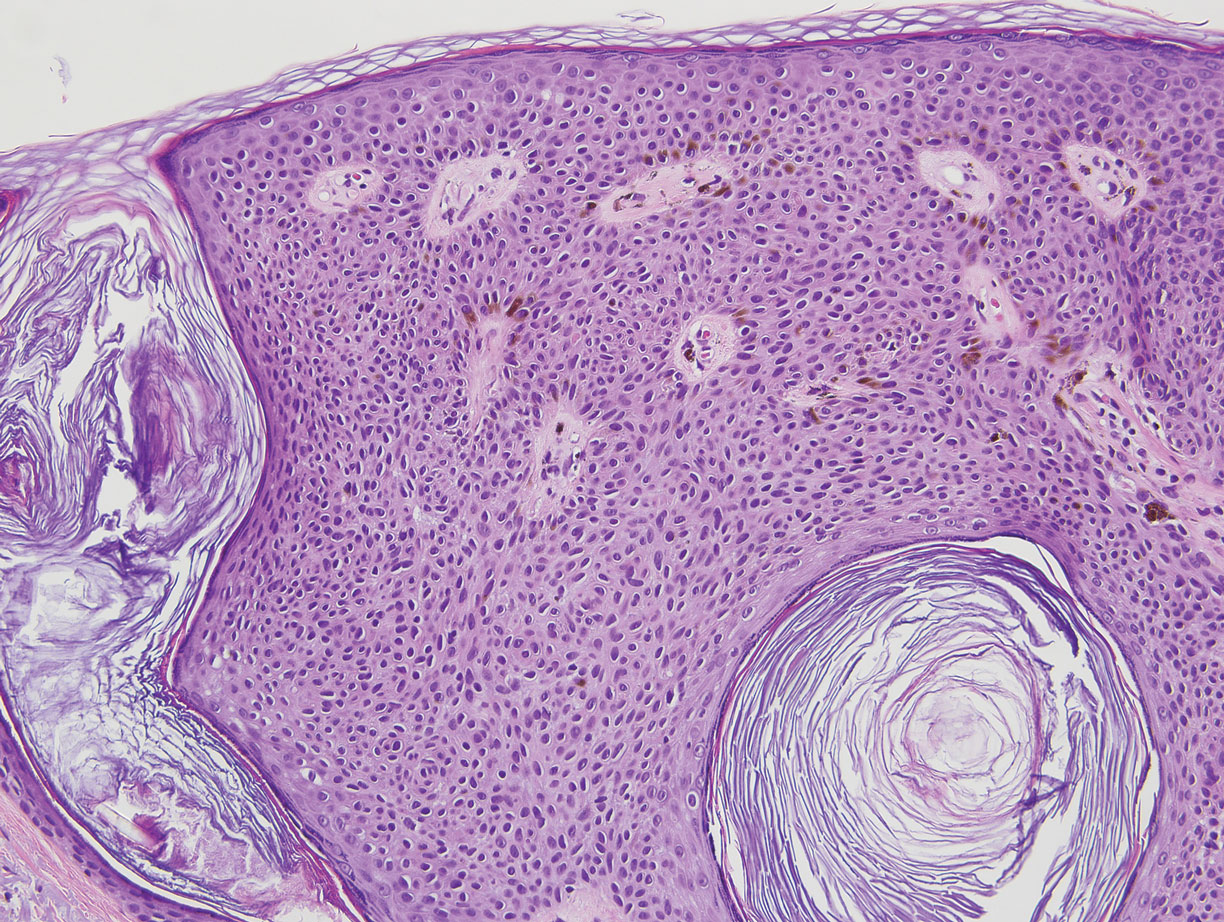

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

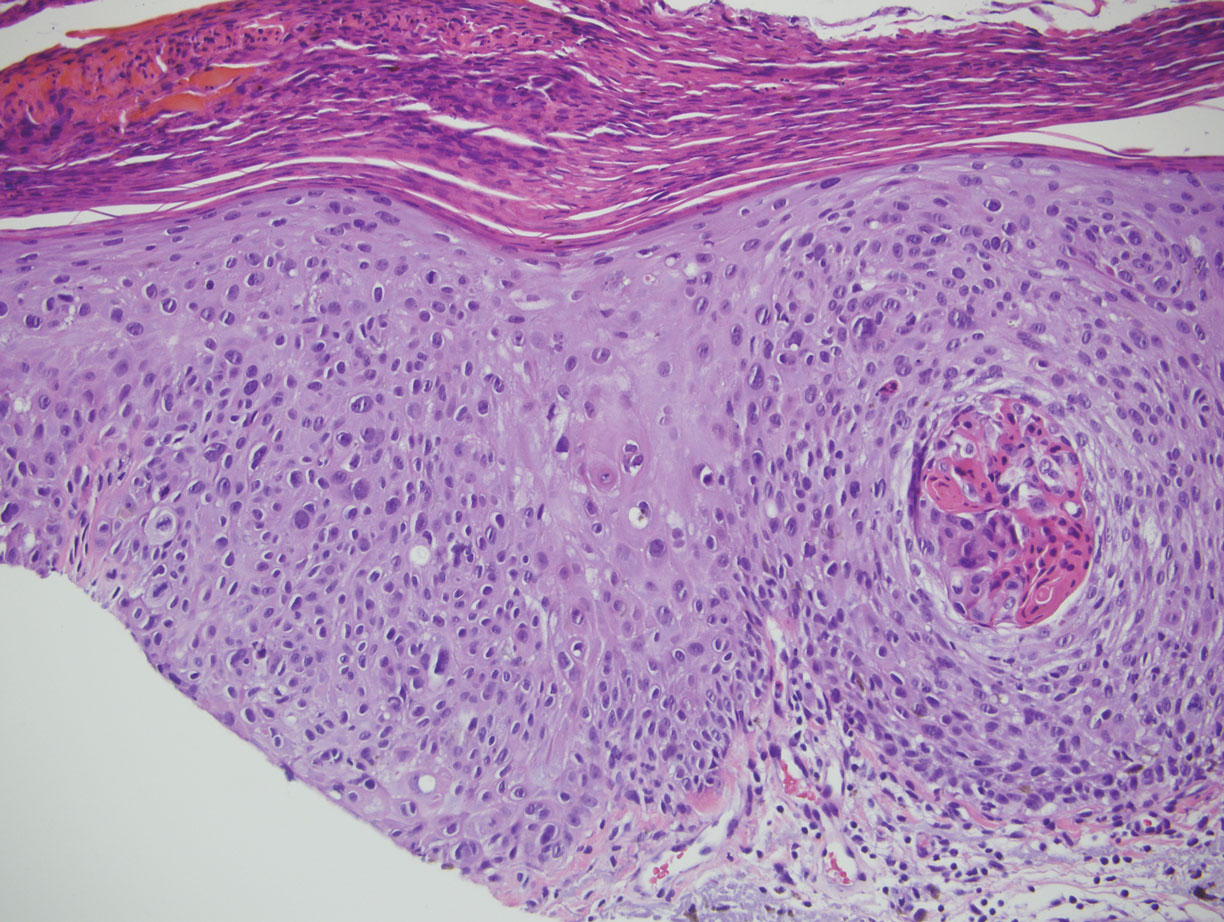

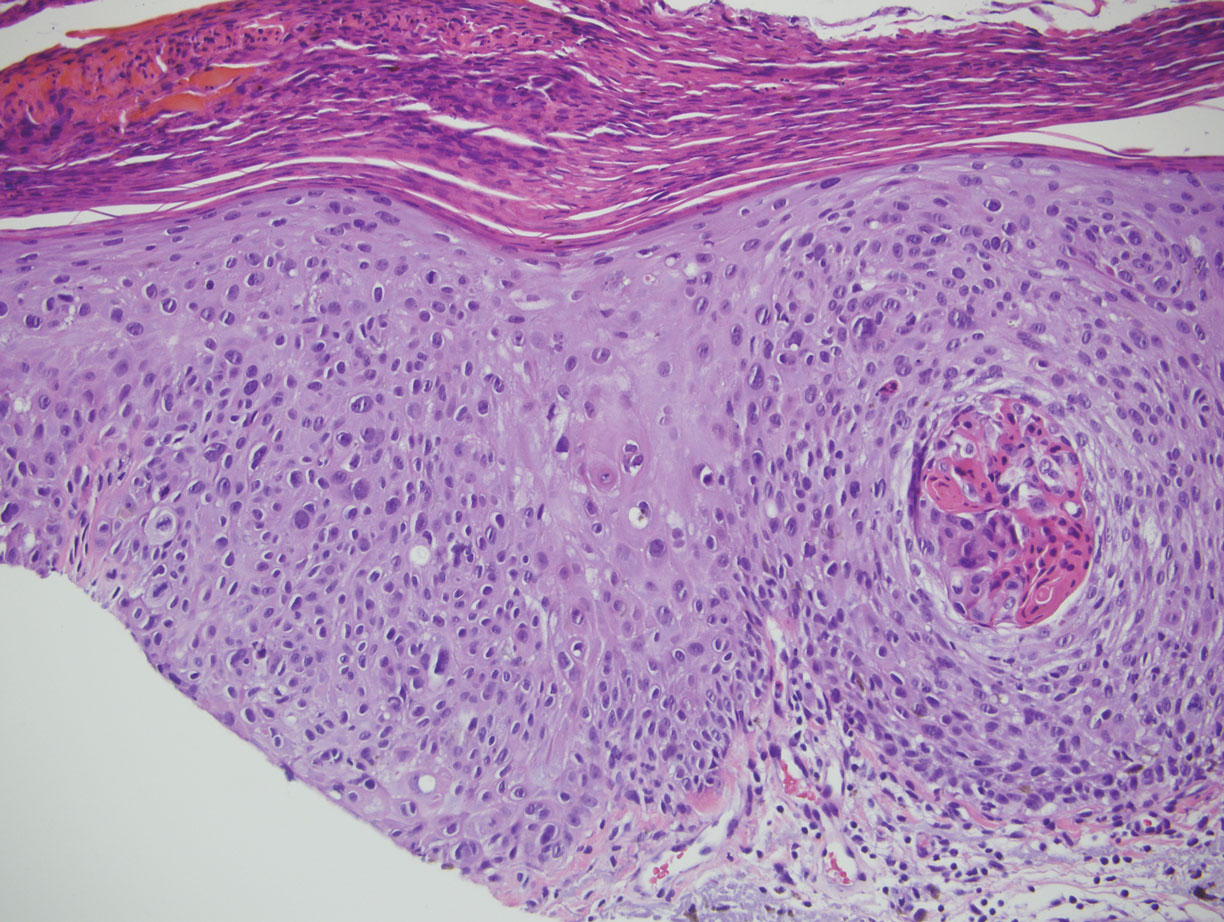

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

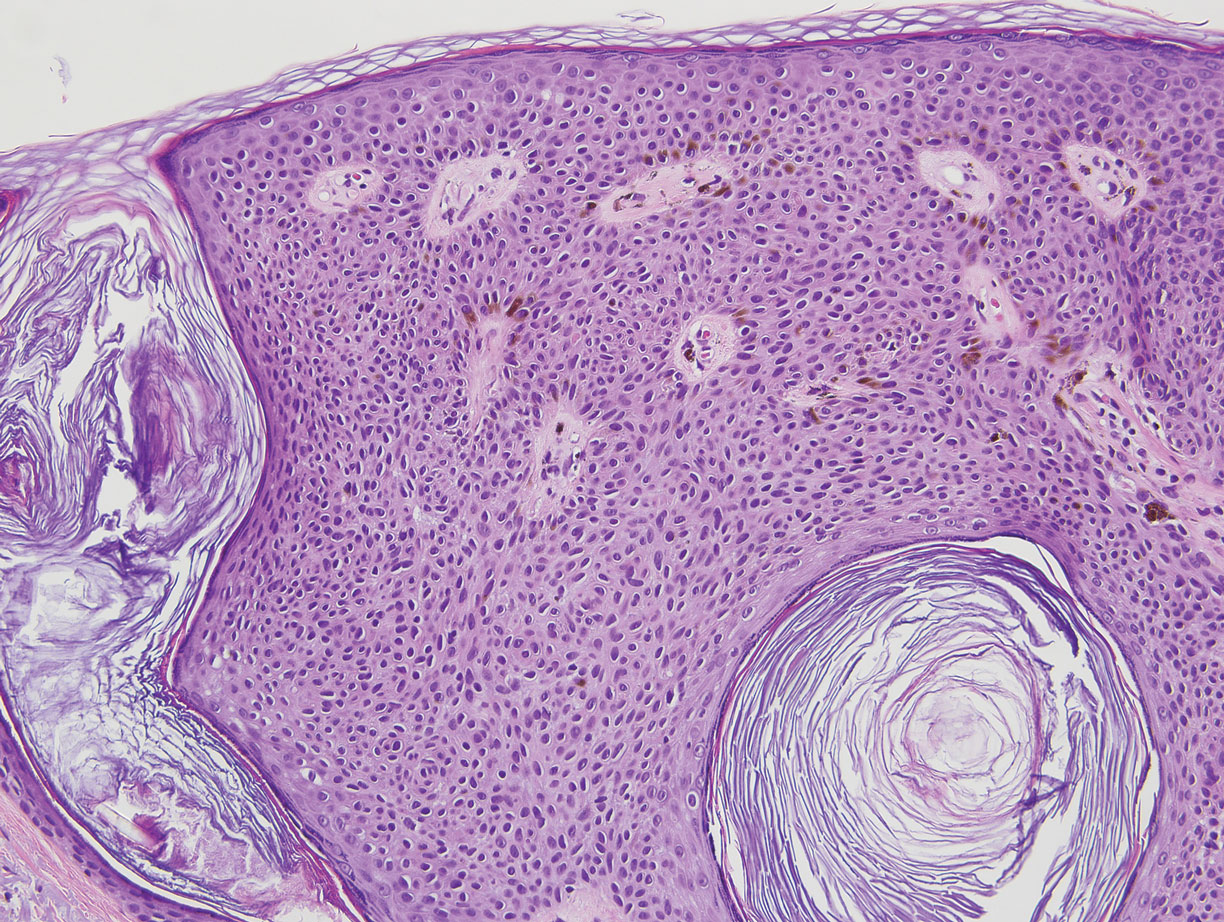

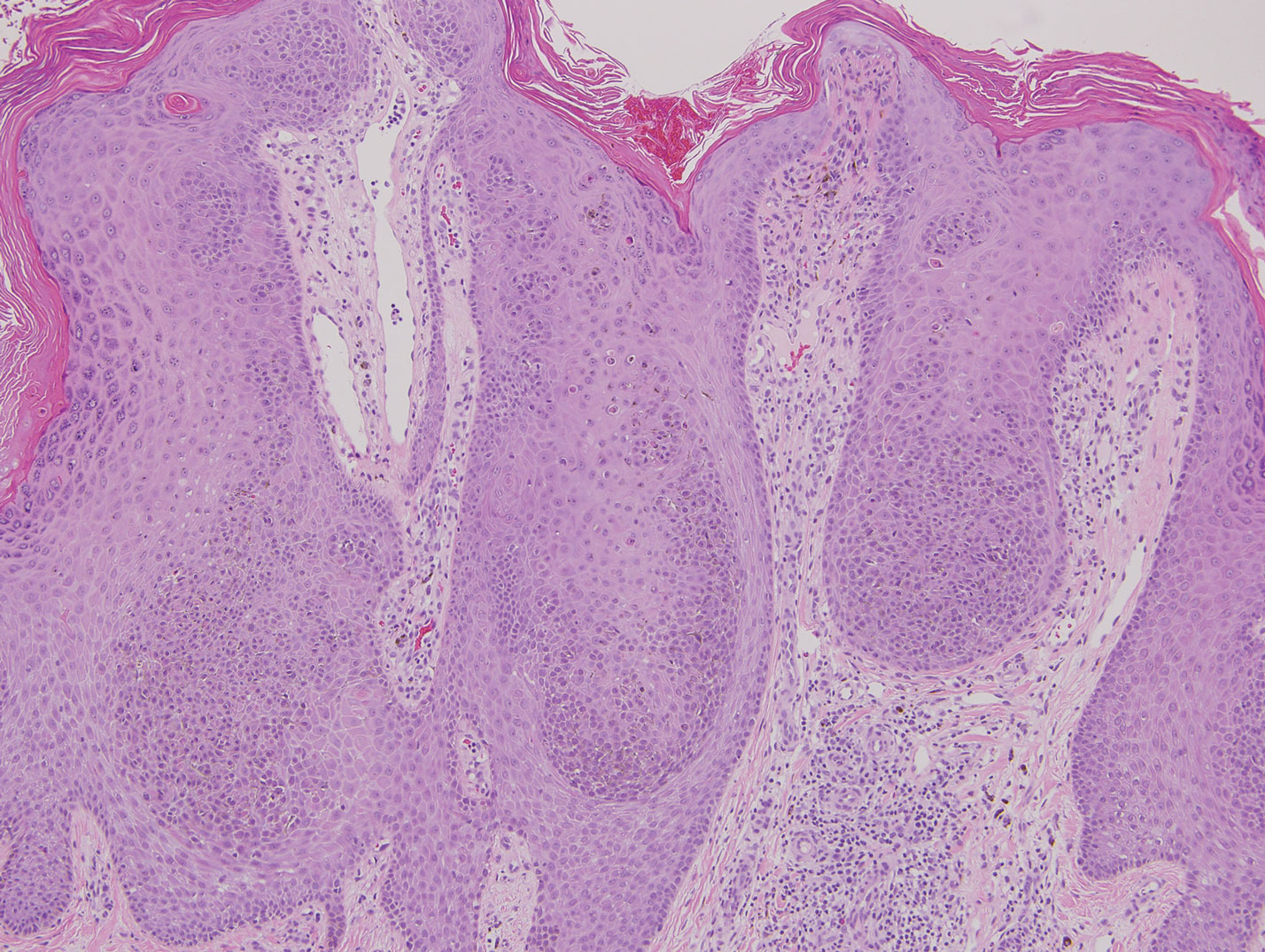

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

A 49-year-old man with light brown skin and no history of skin cancer presented with a pruritic lesion on the scalp of 3 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 7×3-cm, brown, mammillated plaque on the left parietal scalp. A shave biopsy of the scalp lesion was performed.

Streaked Discoloration on the Upper Body

The Diagnosis: Bleomycin-Induced Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Histopathology of the affected skin demonstrated a slight increase in collagen bundle thickness, a chronic dermal perivascular inflammation, and associated pigment incontinence with dermal melanophages compared to unaffected skin (Figure). CD34 was faintly decreased, and dermal mucin increased in affected skin. This postinflammatory pigmentary alteration with subtle dermal sclerosis had persisted unchanged for more than 5 years after cessation of bleomycin therapy. Topical hydroquinone, physical blocker photoprotection, and laser modalities such as the Q-switched alexandrite (755-nm)/Nd:YAG (1064-nm) and ablative CO2 resurfacing lasers were attempted with minimal overall impact on cosmesis.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic antibiotic that has been commonly used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and recurrent malignant pleural effusions.1 The drug is inactivated in most tissues by the enzyme bleomycin hydrolase. This enzyme is not present in skin and lung tissue; as a result, these organs are the most common sites of bleomycin toxicity.1 There are a variety of cutaneous effects associated with bleomycin including alopecia, hyperpigmentation, acral erythema, Raynaud phenomenon, and nail dystrophy.2 Flagellate hyperpigmentation is a less common cutaneous toxicity. It is an unusual eruption that appears as whiplike linear streaks on the upper chest and back, limbs, and flanks.3 This cutaneous manifestation was once thought to be specific to bleomycin use; however, it also has been described in dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease, and after the ingestion of uncooked or undercooked shiitake mushrooms.4 Flagellate hyperpigmentation also was once thought to be dose dependent; however, it has been described in even very small doses.5 The eruption has been described as independent of the route of drug administration, appearing with intravenous, subcutaneous, and intramuscular bleomycin.2 The association of bleomycin and flagellate hyperpigmentation has been reported since 1970; however, it is less commonly seen in clinical practice with the declining use of bleomycin.1

The exact mechanism for the hyperpigmentation is unknown. It has been proposed that the linear lesions are related to areas of pruritus and subsequent excoriations.1 Dermatographism may be present to a limited extent, but it is unlikely to be a chief cause of flagellate hyperpigmentation, as linear streaks have been reported in the absence of trauma. It also has been proposed that bleomycin has a direct toxic effect on the melanocytes, which stimulates increased melanin secretion.2 The hyperpigmentation also may be due to pigmentary incontinence secondary to inflammation.5 Histopathologic findings usually are varied and nonspecific.2 There may be a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, which is nonspecific but can be associated with drug-induced pathology.4 Bleomycin also is used to induce localized scleroderma in mouse-model research6 and has been reported to cause localized scleroderma at an infusion site or after an intralesional injection,7,8 which is not typically reported in flagellate erythema, but bleomycin's sclerosing effects may have played a role in the visible and sclerosing atrophy noted in our patient. Yamamoto et al9 reported a similar case of dermal sclerosis induced by bleomycin.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation typically lasts for up to 6 months.3 Patients with cutaneous manifestations from bleomycin therapy usually respond to steroid therapy and discontinuation of the drug. Bleomycin re-exposure should be avoided, as it may cause extension or widespread recurrence of flagellate hyperpigmentation.3 Postinflammatory pigment alteration may persist in patients with darker skin types and in patients with dramatic inciting inflammation.

Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini is a form of dermal atrophy that presents with 1 or more sharply demarcated depressed patches. There is some debate whether it is a distinct entity or a primary atrophic morphea.10 Linear atrophoderma of Moulin has a similar morphology with hyperpigmented depressions and "cliff-drop" borders, but these lesions follow the lines of Blaschko.11 Linear morphea initially can present as a linear erythematous streak but more commonly appears as a plaque-type morphea lesion that forms a scarlike band.12 Erythema dyschromicum perstans is an ashy dermatosis characterized by gray or blue-brown macules seen in Fitzpatrick skin types III through V and typically is chronic and progressive.13

- Lee HY, Lim KH, Ryu Y, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate erythema: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:933-935.

- Simpson RC, Da Forno P, Nagarajan C, et al. A pruritic rash in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:680-682.

- Fyfe AJ, McKay P. Toxicities associated with bleomycin. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40:213-215.

- Lu CC, Lu YY, Wang QR, et al. Bleomycin-induced flagellate erythema. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:189-190.

- Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

- Yamamoto T. The bleomycin-induced scleroderma model: what have we learned for scleroderma pathogenesis? Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:333-344.

- Kim KH, Yoon TJ, Oh CW, et al. A case of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:454-456.

- Kerr LD, Spiera H. Scleroderma in association with the use of bleomycin: a report of 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:294-296.

- Yamamoto T, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K. Dermal sclerosis in the lesional skin of 'flagellate' erythema (scratch dermatitis) induced by bleomycin. Dermatology. 1998;197:399-400.

- Kencka D, Blaszczyk M, Jablońska S. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini is a primary atrophic abortive morphea. Dermatology. 1995;190:203-206.

- Moulin G, Hill MP, Guillaud V, et al. Acquired atrophic pigmented band-like lesions following Blaschko's lines. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1992;119:729-736.

- Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

- Zaynoun S, Rubeiz N, Kibbi AG. Ashy dermatosis--a critical review of literature and a proposed simplified clinical classification. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:542-544.

The Diagnosis: Bleomycin-Induced Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Histopathology of the affected skin demonstrated a slight increase in collagen bundle thickness, a chronic dermal perivascular inflammation, and associated pigment incontinence with dermal melanophages compared to unaffected skin (Figure). CD34 was faintly decreased, and dermal mucin increased in affected skin. This postinflammatory pigmentary alteration with subtle dermal sclerosis had persisted unchanged for more than 5 years after cessation of bleomycin therapy. Topical hydroquinone, physical blocker photoprotection, and laser modalities such as the Q-switched alexandrite (755-nm)/Nd:YAG (1064-nm) and ablative CO2 resurfacing lasers were attempted with minimal overall impact on cosmesis.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic antibiotic that has been commonly used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and recurrent malignant pleural effusions.1 The drug is inactivated in most tissues by the enzyme bleomycin hydrolase. This enzyme is not present in skin and lung tissue; as a result, these organs are the most common sites of bleomycin toxicity.1 There are a variety of cutaneous effects associated with bleomycin including alopecia, hyperpigmentation, acral erythema, Raynaud phenomenon, and nail dystrophy.2 Flagellate hyperpigmentation is a less common cutaneous toxicity. It is an unusual eruption that appears as whiplike linear streaks on the upper chest and back, limbs, and flanks.3 This cutaneous manifestation was once thought to be specific to bleomycin use; however, it also has been described in dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease, and after the ingestion of uncooked or undercooked shiitake mushrooms.4 Flagellate hyperpigmentation also was once thought to be dose dependent; however, it has been described in even very small doses.5 The eruption has been described as independent of the route of drug administration, appearing with intravenous, subcutaneous, and intramuscular bleomycin.2 The association of bleomycin and flagellate hyperpigmentation has been reported since 1970; however, it is less commonly seen in clinical practice with the declining use of bleomycin.1

The exact mechanism for the hyperpigmentation is unknown. It has been proposed that the linear lesions are related to areas of pruritus and subsequent excoriations.1 Dermatographism may be present to a limited extent, but it is unlikely to be a chief cause of flagellate hyperpigmentation, as linear streaks have been reported in the absence of trauma. It also has been proposed that bleomycin has a direct toxic effect on the melanocytes, which stimulates increased melanin secretion.2 The hyperpigmentation also may be due to pigmentary incontinence secondary to inflammation.5 Histopathologic findings usually are varied and nonspecific.2 There may be a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, which is nonspecific but can be associated with drug-induced pathology.4 Bleomycin also is used to induce localized scleroderma in mouse-model research6 and has been reported to cause localized scleroderma at an infusion site or after an intralesional injection,7,8 which is not typically reported in flagellate erythema, but bleomycin's sclerosing effects may have played a role in the visible and sclerosing atrophy noted in our patient. Yamamoto et al9 reported a similar case of dermal sclerosis induced by bleomycin.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation typically lasts for up to 6 months.3 Patients with cutaneous manifestations from bleomycin therapy usually respond to steroid therapy and discontinuation of the drug. Bleomycin re-exposure should be avoided, as it may cause extension or widespread recurrence of flagellate hyperpigmentation.3 Postinflammatory pigment alteration may persist in patients with darker skin types and in patients with dramatic inciting inflammation.

Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini is a form of dermal atrophy that presents with 1 or more sharply demarcated depressed patches. There is some debate whether it is a distinct entity or a primary atrophic morphea.10 Linear atrophoderma of Moulin has a similar morphology with hyperpigmented depressions and "cliff-drop" borders, but these lesions follow the lines of Blaschko.11 Linear morphea initially can present as a linear erythematous streak but more commonly appears as a plaque-type morphea lesion that forms a scarlike band.12 Erythema dyschromicum perstans is an ashy dermatosis characterized by gray or blue-brown macules seen in Fitzpatrick skin types III through V and typically is chronic and progressive.13

The Diagnosis: Bleomycin-Induced Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Histopathology of the affected skin demonstrated a slight increase in collagen bundle thickness, a chronic dermal perivascular inflammation, and associated pigment incontinence with dermal melanophages compared to unaffected skin (Figure). CD34 was faintly decreased, and dermal mucin increased in affected skin. This postinflammatory pigmentary alteration with subtle dermal sclerosis had persisted unchanged for more than 5 years after cessation of bleomycin therapy. Topical hydroquinone, physical blocker photoprotection, and laser modalities such as the Q-switched alexandrite (755-nm)/Nd:YAG (1064-nm) and ablative CO2 resurfacing lasers were attempted with minimal overall impact on cosmesis.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic antibiotic that has been commonly used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and recurrent malignant pleural effusions.1 The drug is inactivated in most tissues by the enzyme bleomycin hydrolase. This enzyme is not present in skin and lung tissue; as a result, these organs are the most common sites of bleomycin toxicity.1 There are a variety of cutaneous effects associated with bleomycin including alopecia, hyperpigmentation, acral erythema, Raynaud phenomenon, and nail dystrophy.2 Flagellate hyperpigmentation is a less common cutaneous toxicity. It is an unusual eruption that appears as whiplike linear streaks on the upper chest and back, limbs, and flanks.3 This cutaneous manifestation was once thought to be specific to bleomycin use; however, it also has been described in dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease, and after the ingestion of uncooked or undercooked shiitake mushrooms.4 Flagellate hyperpigmentation also was once thought to be dose dependent; however, it has been described in even very small doses.5 The eruption has been described as independent of the route of drug administration, appearing with intravenous, subcutaneous, and intramuscular bleomycin.2 The association of bleomycin and flagellate hyperpigmentation has been reported since 1970; however, it is less commonly seen in clinical practice with the declining use of bleomycin.1

The exact mechanism for the hyperpigmentation is unknown. It has been proposed that the linear lesions are related to areas of pruritus and subsequent excoriations.1 Dermatographism may be present to a limited extent, but it is unlikely to be a chief cause of flagellate hyperpigmentation, as linear streaks have been reported in the absence of trauma. It also has been proposed that bleomycin has a direct toxic effect on the melanocytes, which stimulates increased melanin secretion.2 The hyperpigmentation also may be due to pigmentary incontinence secondary to inflammation.5 Histopathologic findings usually are varied and nonspecific.2 There may be a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, which is nonspecific but can be associated with drug-induced pathology.4 Bleomycin also is used to induce localized scleroderma in mouse-model research6 and has been reported to cause localized scleroderma at an infusion site or after an intralesional injection,7,8 which is not typically reported in flagellate erythema, but bleomycin's sclerosing effects may have played a role in the visible and sclerosing atrophy noted in our patient. Yamamoto et al9 reported a similar case of dermal sclerosis induced by bleomycin.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation typically lasts for up to 6 months.3 Patients with cutaneous manifestations from bleomycin therapy usually respond to steroid therapy and discontinuation of the drug. Bleomycin re-exposure should be avoided, as it may cause extension or widespread recurrence of flagellate hyperpigmentation.3 Postinflammatory pigment alteration may persist in patients with darker skin types and in patients with dramatic inciting inflammation.

Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini is a form of dermal atrophy that presents with 1 or more sharply demarcated depressed patches. There is some debate whether it is a distinct entity or a primary atrophic morphea.10 Linear atrophoderma of Moulin has a similar morphology with hyperpigmented depressions and "cliff-drop" borders, but these lesions follow the lines of Blaschko.11 Linear morphea initially can present as a linear erythematous streak but more commonly appears as a plaque-type morphea lesion that forms a scarlike band.12 Erythema dyschromicum perstans is an ashy dermatosis characterized by gray or blue-brown macules seen in Fitzpatrick skin types III through V and typically is chronic and progressive.13

- Lee HY, Lim KH, Ryu Y, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate erythema: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:933-935.

- Simpson RC, Da Forno P, Nagarajan C, et al. A pruritic rash in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:680-682.

- Fyfe AJ, McKay P. Toxicities associated with bleomycin. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40:213-215.

- Lu CC, Lu YY, Wang QR, et al. Bleomycin-induced flagellate erythema. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:189-190.

- Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

- Yamamoto T. The bleomycin-induced scleroderma model: what have we learned for scleroderma pathogenesis? Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:333-344.

- Kim KH, Yoon TJ, Oh CW, et al. A case of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:454-456.

- Kerr LD, Spiera H. Scleroderma in association with the use of bleomycin: a report of 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:294-296.

- Yamamoto T, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K. Dermal sclerosis in the lesional skin of 'flagellate' erythema (scratch dermatitis) induced by bleomycin. Dermatology. 1998;197:399-400.

- Kencka D, Blaszczyk M, Jablońska S. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini is a primary atrophic abortive morphea. Dermatology. 1995;190:203-206.

- Moulin G, Hill MP, Guillaud V, et al. Acquired atrophic pigmented band-like lesions following Blaschko's lines. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1992;119:729-736.

- Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

- Zaynoun S, Rubeiz N, Kibbi AG. Ashy dermatosis--a critical review of literature and a proposed simplified clinical classification. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:542-544.

- Lee HY, Lim KH, Ryu Y, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate erythema: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:933-935.

- Simpson RC, Da Forno P, Nagarajan C, et al. A pruritic rash in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:680-682.

- Fyfe AJ, McKay P. Toxicities associated with bleomycin. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40:213-215.

- Lu CC, Lu YY, Wang QR, et al. Bleomycin-induced flagellate erythema. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:189-190.

- Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

- Yamamoto T. The bleomycin-induced scleroderma model: what have we learned for scleroderma pathogenesis? Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:333-344.

- Kim KH, Yoon TJ, Oh CW, et al. A case of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:454-456.

- Kerr LD, Spiera H. Scleroderma in association with the use of bleomycin: a report of 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:294-296.

- Yamamoto T, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K. Dermal sclerosis in the lesional skin of 'flagellate' erythema (scratch dermatitis) induced by bleomycin. Dermatology. 1998;197:399-400.

- Kencka D, Blaszczyk M, Jablońska S. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini is a primary atrophic abortive morphea. Dermatology. 1995;190:203-206.

- Moulin G, Hill MP, Guillaud V, et al. Acquired atrophic pigmented band-like lesions following Blaschko's lines. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1992;119:729-736.

- Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

- Zaynoun S, Rubeiz N, Kibbi AG. Ashy dermatosis--a critical review of literature and a proposed simplified clinical classification. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:542-544.

An 18-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with persistent diffuse discoloration on the upper body of more than 5 years’ duration. Her medical history was notable for primary mediastinal classical Hodgkin lymphoma treated with ABVE-PC (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy and 22 Gy radiation therapy to the chest 5 years prior. She reported the initial onset of diffuse pruritus with associated scratching and persistent skin discoloration while receiving a course of chemotherapy. Physical examination revealed numerous thin, flagellate, faintly hyperpigmented streaks with subtle atrophy in a parallel configuration on the bilateral shoulders (top), upper back (bottom), and abdomen. Punch biopsies (5 mm) of both affected and unaffected skin on the left side of the lateral upper back were performed.

Chronic Diffuse Erythematous Papulonodules

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

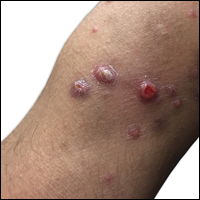

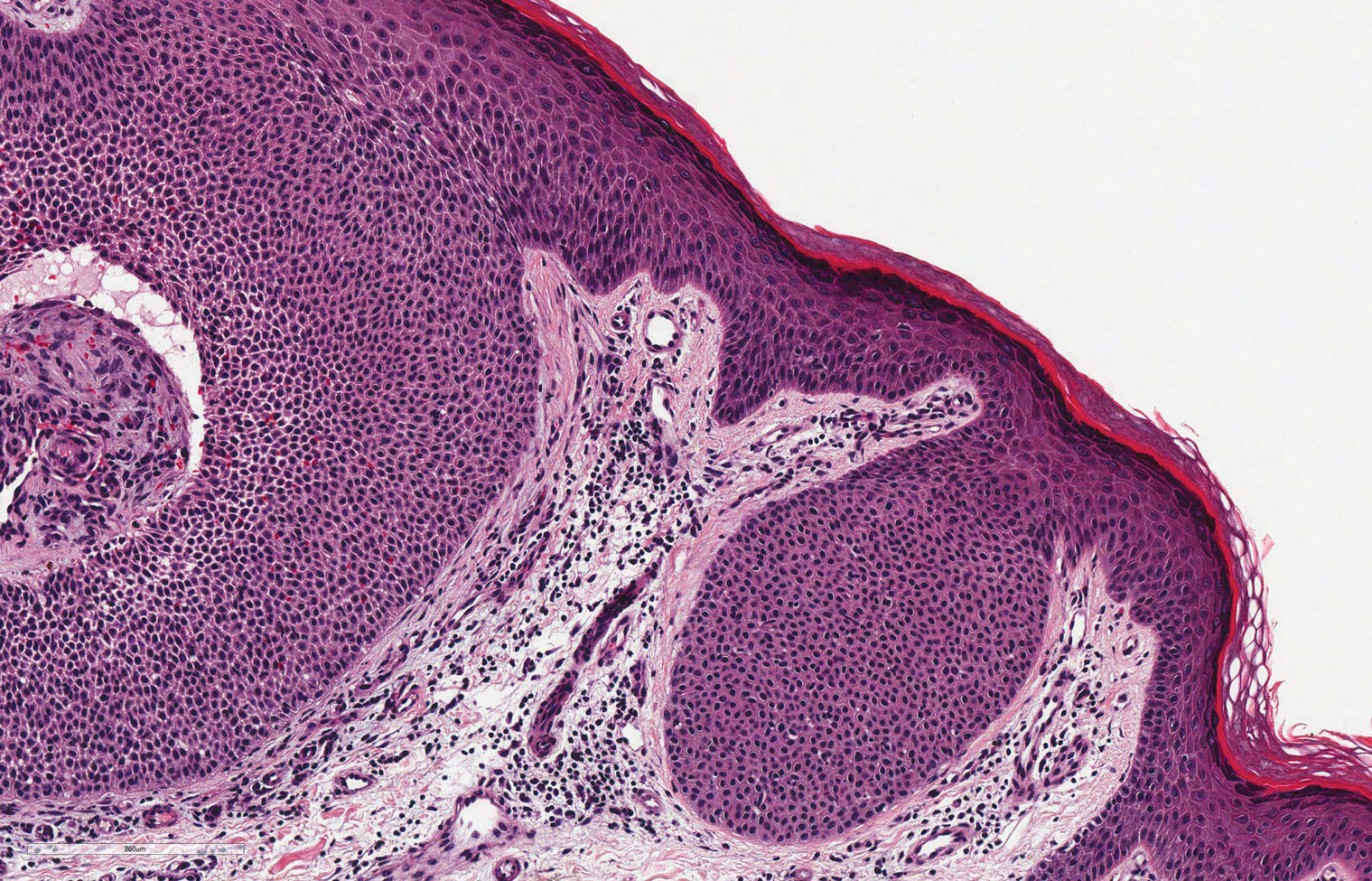

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

A 29-year-old man from Saudi Arabia presented with slightly tender skin lesions occurring in crops every few months over the last 7 years. The lesions typically would occur on the inguinal area, lower abdomen, buttocks, thighs, or arms, resolving within a few weeks despite no treatment. The patient denied having systemic symptoms such as fevers, chills, sweats, chest pain, shortness of breath, or unexpected weight loss. Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous papulonodules, some ulcerated with a superficial crust, grouped predominantly on the medial aspect of the right upper arm and left lower inguinal region. Isolated lesions also were present on the forearms, dorsal aspects of the hands, abdomen, and thighs. The grouped papulonodules were intermixed with faint hyperpigmented macules indicative of prior lesions. No oral lesions were noted, and there was no marked axillary or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Expanding Pruritic Plaque on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Protothecosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy of the plaque on the right forearm was performed. The biopsy showed chronic inflammation with prominent histiocytes, foreign body giant cells, plasma cells, and abundant eosinophils (Figure 1). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated abundant soccer ball-like or floretlike sporangia that were 3 to 11 μm, consistent with a diagnosis of protothecosis (Figure 2).

Cutaneous protothecosis is an infection caused by chlorophyll-lacking algae of the genus Prototheca.1 It is ubiquitous in nature and can be isolated from various reservoirs such as trees, grass, water, and food sources.2 Protothecosis is present worldwide and in the United States; it is most prevalent in the Southeast. Prototheca species are rare but often endemic in cattle and can cause bovine mastitis and enteritis.3 However, they are rare opportunistic infections in humans.

The pathogenesis of cutaneous protothecosis is largely unknown.4 However, most infections are thought to be caused by traumatic inoculation into subcutaneous tissues.1,2 The majority of cases occur in patients older than 30 years. To date, approximately 160 cases have been reported in the literature worldwide.5 There are 3 main species of Prototheca, but almost all human infections are caused by Prototheca wickerhamii.2 Clinically, most patients with protothecosis present with cutaneous findings, but olecranon bursitis and systemic forms also have been reported.1

Risk factors for protothecosis include immunosuppression, most often due to steroids, in addition to malignancies, diabetes mellitus, and certain occupations.1 The presentation can be variable from papules and plaques to even herpetiform appearances.4 Protothecosis usually affects the skin and soft tissues of exposed areas such as the extremities or the face.6 Diagnosis largely is made on detection of characteristic floretlike sporangia with a prominent cell wall on histopathological examination. Prototheca wickerhamii specifically produces a morula form of sporangia with endospores arranged symmetrically, giving it a characteristic soccer ball appearance.2

Treatment of protothecosis is difficult and remains controversial.1 There are no established protothecosis treatment protocols or guidelines due to the small number of cases.7 In vitro studies have demonstrated sensitivity to amphotericin B and various azoles as well as a wide range of antibiotics.1 Olecranon bursitis and small skin lesions can be treated by surgical excision. All other Prototheca infections require systemic treatment with azoles or intravenous amphotericin B for immunocompromised patients or those with disseminated disease.5 However, failure to respond to medical management often occurs, requiring surgical excision.1,6

Our patient was treated with a 3-month course of voriconazole but therapy failed and the plaque continued to expand. The patient underwent a wide excision that was repaired with a partial-thickness skin graft. Rebiopsy of the papule adjacent to the skin graft showed no further recurrence.

In conclusion, protothecosis generally is not clinically suspected and patients are subjected to various treatments without adequate results. A definitive diagnosis easily can be established with a skin biopsy, which can direct timely and appropriate treatment.

- Lass-Flörl C, Mary A. Human protothecosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:230-242.

- Mayorga J, Barba-Gómez JF, Verduzco-Martínez AP, et al. Protothecosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:432-436.

- Jensen HE, Aalbaek B, Bloch B, et al. Bovine mammary protothecosis due to Prototheca zopfii. Med Mycol. 1998;36:89-95.

- Boyd AS, Langley M, King LE Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of Prototheca infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:758-764.

- Todd JR, King JW, Oberle A, et al. Protothecosis: report of a case with 20-year follow-up, and review of previously published cases. Med Mycol. 2012;50:673-689.

- Hightower KD, Messina JL. Cutaneous protothecosis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;80:129-131.

- Yamada N, Yoshida Y, Ohsawa T, et al. A case of cutaneous protothecosis successfully treated with local thermal therapy as an adjunct to itraconazole therapy in an immunocompromised host. Med Mycol. 2010;48:643-646.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Protothecosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy of the plaque on the right forearm was performed. The biopsy showed chronic inflammation with prominent histiocytes, foreign body giant cells, plasma cells, and abundant eosinophils (Figure 1). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated abundant soccer ball-like or floretlike sporangia that were 3 to 11 μm, consistent with a diagnosis of protothecosis (Figure 2).

Cutaneous protothecosis is an infection caused by chlorophyll-lacking algae of the genus Prototheca.1 It is ubiquitous in nature and can be isolated from various reservoirs such as trees, grass, water, and food sources.2 Protothecosis is present worldwide and in the United States; it is most prevalent in the Southeast. Prototheca species are rare but often endemic in cattle and can cause bovine mastitis and enteritis.3 However, they are rare opportunistic infections in humans.

The pathogenesis of cutaneous protothecosis is largely unknown.4 However, most infections are thought to be caused by traumatic inoculation into subcutaneous tissues.1,2 The majority of cases occur in patients older than 30 years. To date, approximately 160 cases have been reported in the literature worldwide.5 There are 3 main species of Prototheca, but almost all human infections are caused by Prototheca wickerhamii.2 Clinically, most patients with protothecosis present with cutaneous findings, but olecranon bursitis and systemic forms also have been reported.1

Risk factors for protothecosis include immunosuppression, most often due to steroids, in addition to malignancies, diabetes mellitus, and certain occupations.1 The presentation can be variable from papules and plaques to even herpetiform appearances.4 Protothecosis usually affects the skin and soft tissues of exposed areas such as the extremities or the face.6 Diagnosis largely is made on detection of characteristic floretlike sporangia with a prominent cell wall on histopathological examination. Prototheca wickerhamii specifically produces a morula form of sporangia with endospores arranged symmetrically, giving it a characteristic soccer ball appearance.2

Treatment of protothecosis is difficult and remains controversial.1 There are no established protothecosis treatment protocols or guidelines due to the small number of cases.7 In vitro studies have demonstrated sensitivity to amphotericin B and various azoles as well as a wide range of antibiotics.1 Olecranon bursitis and small skin lesions can be treated by surgical excision. All other Prototheca infections require systemic treatment with azoles or intravenous amphotericin B for immunocompromised patients or those with disseminated disease.5 However, failure to respond to medical management often occurs, requiring surgical excision.1,6

Our patient was treated with a 3-month course of voriconazole but therapy failed and the plaque continued to expand. The patient underwent a wide excision that was repaired with a partial-thickness skin graft. Rebiopsy of the papule adjacent to the skin graft showed no further recurrence.

In conclusion, protothecosis generally is not clinically suspected and patients are subjected to various treatments without adequate results. A definitive diagnosis easily can be established with a skin biopsy, which can direct timely and appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Protothecosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy of the plaque on the right forearm was performed. The biopsy showed chronic inflammation with prominent histiocytes, foreign body giant cells, plasma cells, and abundant eosinophils (Figure 1). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated abundant soccer ball-like or floretlike sporangia that were 3 to 11 μm, consistent with a diagnosis of protothecosis (Figure 2).

Cutaneous protothecosis is an infection caused by chlorophyll-lacking algae of the genus Prototheca.1 It is ubiquitous in nature and can be isolated from various reservoirs such as trees, grass, water, and food sources.2 Protothecosis is present worldwide and in the United States; it is most prevalent in the Southeast. Prototheca species are rare but often endemic in cattle and can cause bovine mastitis and enteritis.3 However, they are rare opportunistic infections in humans.

The pathogenesis of cutaneous protothecosis is largely unknown.4 However, most infections are thought to be caused by traumatic inoculation into subcutaneous tissues.1,2 The majority of cases occur in patients older than 30 years. To date, approximately 160 cases have been reported in the literature worldwide.5 There are 3 main species of Prototheca, but almost all human infections are caused by Prototheca wickerhamii.2 Clinically, most patients with protothecosis present with cutaneous findings, but olecranon bursitis and systemic forms also have been reported.1

Risk factors for protothecosis include immunosuppression, most often due to steroids, in addition to malignancies, diabetes mellitus, and certain occupations.1 The presentation can be variable from papules and plaques to even herpetiform appearances.4 Protothecosis usually affects the skin and soft tissues of exposed areas such as the extremities or the face.6 Diagnosis largely is made on detection of characteristic floretlike sporangia with a prominent cell wall on histopathological examination. Prototheca wickerhamii specifically produces a morula form of sporangia with endospores arranged symmetrically, giving it a characteristic soccer ball appearance.2

Treatment of protothecosis is difficult and remains controversial.1 There are no established protothecosis treatment protocols or guidelines due to the small number of cases.7 In vitro studies have demonstrated sensitivity to amphotericin B and various azoles as well as a wide range of antibiotics.1 Olecranon bursitis and small skin lesions can be treated by surgical excision. All other Prototheca infections require systemic treatment with azoles or intravenous amphotericin B for immunocompromised patients or those with disseminated disease.5 However, failure to respond to medical management often occurs, requiring surgical excision.1,6

Our patient was treated with a 3-month course of voriconazole but therapy failed and the plaque continued to expand. The patient underwent a wide excision that was repaired with a partial-thickness skin graft. Rebiopsy of the papule adjacent to the skin graft showed no further recurrence.

In conclusion, protothecosis generally is not clinically suspected and patients are subjected to various treatments without adequate results. A definitive diagnosis easily can be established with a skin biopsy, which can direct timely and appropriate treatment.

- Lass-Flörl C, Mary A. Human protothecosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:230-242.

- Mayorga J, Barba-Gómez JF, Verduzco-Martínez AP, et al. Protothecosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:432-436.

- Jensen HE, Aalbaek B, Bloch B, et al. Bovine mammary protothecosis due to Prototheca zopfii. Med Mycol. 1998;36:89-95.

- Boyd AS, Langley M, King LE Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of Prototheca infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:758-764.

- Todd JR, King JW, Oberle A, et al. Protothecosis: report of a case with 20-year follow-up, and review of previously published cases. Med Mycol. 2012;50:673-689.

- Hightower KD, Messina JL. Cutaneous protothecosis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;80:129-131.

- Yamada N, Yoshida Y, Ohsawa T, et al. A case of cutaneous protothecosis successfully treated with local thermal therapy as an adjunct to itraconazole therapy in an immunocompromised host. Med Mycol. 2010;48:643-646.

- Lass-Flörl C, Mary A. Human protothecosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:230-242.

- Mayorga J, Barba-Gómez JF, Verduzco-Martínez AP, et al. Protothecosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:432-436.

- Jensen HE, Aalbaek B, Bloch B, et al. Bovine mammary protothecosis due to Prototheca zopfii. Med Mycol. 1998;36:89-95.

- Boyd AS, Langley M, King LE Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of Prototheca infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:758-764.

- Todd JR, King JW, Oberle A, et al. Protothecosis: report of a case with 20-year follow-up, and review of previously published cases. Med Mycol. 2012;50:673-689.

- Hightower KD, Messina JL. Cutaneous protothecosis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;80:129-131.

- Yamada N, Yoshida Y, Ohsawa T, et al. A case of cutaneous protothecosis successfully treated with local thermal therapy as an adjunct to itraconazole therapy in an immunocompromised host. Med Mycol. 2010;48:643-646.

A 66-year-old male firefighter initially presented to the emergency department with an expanding pruritic plaque on the dorsal aspect of the right forearm. The patient recalled the appearance of a single 3-mm papule shortly after doing yardwork in Biloxi, Mississippi. He remembered getting wet grass on the arms, which he later washed off without any notable trauma. The single papule grew into a larger plaque over the next month. In the emergency department he was treated with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, mupirocin, and clotrimazole without response. He was referred to the dermatology department 6 months later and was noted to have multiple 3- to 4-mm papules that coalesced into a 4-cm lichenified plaque with surrounding erythema on the right forearm. His medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. The remainder of the physical examination and review of systems was negative.