User login

Implementing the EQUiPPED Medication Management Program

Suboptimal prescribing for older adults discharged from the emergency department (ED) is a recognized problem.1-4 At the Durham VAMC in North Carolina, for example, suboptimal prescribing was tracked in about 30% of patients discharged from the ED; 34% experienced an adverse medical event within 90 days, including repeated ED visits, hospitalization, or death.4

In 2012, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) issued its Beers Criteria list of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to avoid (updated again in 2015).5,6 As EDs are not suited to meet the needs of a vulnerable population with complex medical conditions and medication regimens, putting these evidence-based guidelines into practice represented both a challenge and an opportunity.7

In 2013, an investigator from the Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) teamed up with an internist at the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia to expand a local quality improvement intervention to reduce the use of PIMs prescribed to veterans at time of discharge from the ED. The project received funding from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Transforming VA Healthcare for the 21st Century (T-21) initiative for a 3-site quality improvement project. In the second year, the project was expanded to 5 sites representing a collaboration of 4 different GRECCs.

With a common mission to develop and evaluate new models of geriatric care for veterans, GRECCs offer a national network for rapid implementation and potential dissemination of innovative clinical demonstration projects. Preliminary evaluation showed a significant and sustained reduction of ED-prescribed PIMs at the first implementation site, with favorable results suggested by subsequent sites.8,9

These results demonstrated success despite implementation challenges, including creating order sets and educating clinicians to change behavior. This article describes common and diverging factors across 5 implementation sites and presents an implementation process model that was developed by examining these factors.

Implementation

Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Dis-charged from the ED (EQUiPPED) is a multicomponent, interdisciplinaryquality-improvement initiative to reduce PIMs. The program imple-mented 3 evidence-based inter-ventions: (1) ED provider education; (2) clinical decision support in the form of pharmacy quick-order sets; and (3) individual provider academic detailing, audit and feedback, and peer benchmarking. 10,11

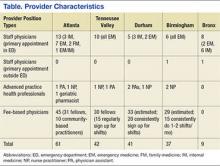

The original implementation sites in September 2013 were the Atlanta VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC), the Durham VAMC (Durham GRECC), and the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System Nashville Campus (Tennessee Valley GRECC). In September 2014 the James J. Peters VAMC (Bronx GRECC) and the Birmingham VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC) also were included. Provider characteristics varied by site (Table).

To ensure that the program was consistently implemented at each site, several standard definitions and formulas were developed. The investigators defined 34 PIMs and classes to avoid in adults aged ≥ 65 years regardless of diseases or conditions from the 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.5 However, the Beers List required interpretation on several important points. For example, the Beers List does not advise on how PIMs are to be measured and tracked. Also, it does not specify a goal other than to “improve care of older adults by reducing their exposure to PIMs.”5

Potentially inappropriate medications are now recognized as an important measure by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) and are used as a quality measure in the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). They are typically measured as the number of patients aged ≥ 65 years who received either at least 1 PIM or at least 2 PIMs divided by the total number of patients aged ≥ 65 years during a given period (typically a year). The EQUiPPED program, however, is an intervention targeting providers rather than patients, and for regular monthly feedback, the EQUiPPED team designated its measure as the number of PIMs prescribed to veterans aged ≥ 65 years on discharge from the ED divided by the total number of medications prescribed at discharge in a particular month. Understanding that PIMs are sometimes necessary for treatment, the EQUiPPED team set a goal of reducing PIMs prescribed to below 5% of all discharge medications in the ED.

The EQUiPPED implementation team also operationalized other aspects of the Beers List recommendations. For example, providers are advised that oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should not be prescribed for chronic use “unless other alternatives are not effective and the patient can take a gastroprotective agent.”12 However, there is no guidance on the meaning of chronic use or on dosages. The team determined that the best operational definition of chronic NSAID use for EQUiPPED was prescription duration of ≥ 30 days.

To carry out the intervention, each EQUiPPED site used a letter from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care designating the analysis of outcomes data related to the intervention as an operational activity rather than as research. The EQUiPPED team developed pharmacy quick-order sets in dialogue with ED providers and clinical pharmacists. Clinical applications coordinators facilitated local integration of order sets into the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Local clinical experts reviewed the order sets (eg, the Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee, the Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee, and the Chief of Pharmacy Service) before implementation.

Once the order sets were implemented, the sites began educating providers about the order sets along with the information about Beers List medications. As soon as possible, usually 1 month after the educational sessions, the sites began evaluating data from the local corporate data warehouse regarding medications prescribed in order to calculate monthly PIM rates. Each provider received a report that showed their PIM rate and overall prescribing in the previous month and benchmarked this performance in relation to anonymized peers. The first feedback session was given in person by a physician or a physician-pharmacist team. All sites followed these standard EQUiPPED procedures.

Site Innovations and Adaptations

The Durham site developed a Beers List look-up tool to streamline the calculation of PIMs per provider every month and ensure the systematization of procedures. Although each site introduced education, order sets, and feedback in the same order, launch times differed. Varying levels of staff availability and expertise resulted in order-set rollout times that ranged from 3 weeks to 12 months. Some sites launched additional tools. For example, Durham, Atlanta, and Bronx added blue line alerts, a noninterruptive informational message in CPRS for every Beers List drug prescribed at their VA that warned prescribers to “use with caution in patients 65+.”

Some sites physically placed caution cards on the edge of ED computer screens listing the top 5 PIMS drugs at that site. Nashville, Birmingham, and Durham’s order sets included links to external sites, such as the World Health Organization analgesic ladder and to narcotics equivalency tables to simplify pain management. Nashville ED providers requested e-mail attachments of Beers List drugs, Beers alternatives, and reminders with monthly feedback reports.

Other differences depended on the makeup of the EQUiPPED intervention team and the patient population at each site. A physician champion within the ED, a geriatrician, and a geriatric pharmacist directed the lead Atlanta site. In contrast, a geriatrician led the Durham project and used incentives to help encourage ED provider participation. All Durham ED providers who participated in the program received laminated Beers pocket cards, a printed guide to download the Geriatrics at Your Fingertips app, and a gift card to purchase the app. Other sites distributed some of these materials but did not include the gift card.

Durham-trained resident physicians rotated through the ED each month, as did Atlanta’s. Durham also introduced pre- and posttraining quizzes for resident physicians to test knowledge gained.13 No other site followed this pattern. Differences in local formularies, priorities, patient groups, and preferences led sites to select different order sets for presentation and to adapt them if needed.

Tennessee Valley posted the largest array of order sets in the CPRS with 42 different medication order sets, Atlanta and Birmingham had 12 order sets, and Bronx used the fewest at 3. Durham chose to implement its order sets progressively, with an initial 3, then an additional 2, and then an additional 2. Durham sought feedback from providers during this staged rollout and incorporated changes into the development of the next set. Birmingham and Bronx began tracking use of order sets electronically. The Atlanta site conducted qualitative interviews with a subset of providers (both untrained and trained) to evaluate usage patterns. Nashville used the geriatric order sets as a template to develop order sets for other emergency conditions.

Implementation Model

By understanding practice variations and similarities at a heterogeneous group of VA hospitals, tracking prescribing data, and conducting a thematic content analysis of field reports from EQUiPPED sites, the investigators were able to develop a relatively standardized process model to improve ED prescribing practices for clinicians caring for older adults. The implementation model captures factors at the level of context (alignment with priorities of care), inputs (resources available), outputs (activities and participation), and outcomes (short, medium, and long-term). In addition to the process model, EQUiPPED has developed an implementation tool kit, which includes order set logic, the Beers look-up tool developed by Durham, education materials, and provider feedback templates.

The implementation model and components of the tool kit are available by request through the Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC. With these materials, the EQUiPPED project is poised for implementation at other VA EDs or at sites beyond the VA.

Conclusion

Successful implementation of EQUiPPED, an innovative geriatric practice intervention to reduce PIM prescribing in the ED, is dependent on careful planning and site customization. Distilling factors that differed across VA sites resulted in a model intended to promote implementation and dissemination of the EQUIPPED intervention.

1. Beers MH, Storrie M, Lee G. Potential adverse drug interactions in the emergency room: an issue in the quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(1):61-64.

2. Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, et al. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(12):1232-1242.

3. Hustey FM, Wallis N, Miller J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):804-807.

4. Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, et al. Quality of pharmacotherapy and outcomes for older veterans discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):875-880.

5. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

7. Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2116-2121.

8. Stevens MB, Hastings SN, Powers J, et al. Enhancing the Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department (EQUiPPED): preliminary results from Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department, a novel multicomponent interdisciplinary quality improvement initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):1025-1029.

9. Moss JM, Bryan WE, Wilkerson LM, et al. Impact of clinical pharmacy specialists on the design and implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease inappropriate medications in a Veterans Affairs emergency deepartment. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(1):74-80.

10. O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409.

11. Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Dexter PR, Hui SL, Callahan CM, Miller DK. Computerized decision support to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing to older emergency department patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1388-1394.

12. The American Geriatrics Association. A Pocket Guide to the AGS Beers Criteria. New York, NY: The American Geriatrics Association; 2012.

13. Wilkerson LM, Owenby R, Bryan W, et al. An interdisciplinary academic detailing approach to decrease inappropriate medication prescribing for older veterans treated in the Emergency Department. In: Proceeding from the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting; May 14-17, 2015; National Harbor, MD. Abstract B67.

Suboptimal prescribing for older adults discharged from the emergency department (ED) is a recognized problem.1-4 At the Durham VAMC in North Carolina, for example, suboptimal prescribing was tracked in about 30% of patients discharged from the ED; 34% experienced an adverse medical event within 90 days, including repeated ED visits, hospitalization, or death.4

In 2012, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) issued its Beers Criteria list of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to avoid (updated again in 2015).5,6 As EDs are not suited to meet the needs of a vulnerable population with complex medical conditions and medication regimens, putting these evidence-based guidelines into practice represented both a challenge and an opportunity.7

In 2013, an investigator from the Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) teamed up with an internist at the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia to expand a local quality improvement intervention to reduce the use of PIMs prescribed to veterans at time of discharge from the ED. The project received funding from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Transforming VA Healthcare for the 21st Century (T-21) initiative for a 3-site quality improvement project. In the second year, the project was expanded to 5 sites representing a collaboration of 4 different GRECCs.

With a common mission to develop and evaluate new models of geriatric care for veterans, GRECCs offer a national network for rapid implementation and potential dissemination of innovative clinical demonstration projects. Preliminary evaluation showed a significant and sustained reduction of ED-prescribed PIMs at the first implementation site, with favorable results suggested by subsequent sites.8,9

These results demonstrated success despite implementation challenges, including creating order sets and educating clinicians to change behavior. This article describes common and diverging factors across 5 implementation sites and presents an implementation process model that was developed by examining these factors.

Implementation

Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Dis-charged from the ED (EQUiPPED) is a multicomponent, interdisciplinaryquality-improvement initiative to reduce PIMs. The program imple-mented 3 evidence-based inter-ventions: (1) ED provider education; (2) clinical decision support in the form of pharmacy quick-order sets; and (3) individual provider academic detailing, audit and feedback, and peer benchmarking. 10,11

The original implementation sites in September 2013 were the Atlanta VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC), the Durham VAMC (Durham GRECC), and the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System Nashville Campus (Tennessee Valley GRECC). In September 2014 the James J. Peters VAMC (Bronx GRECC) and the Birmingham VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC) also were included. Provider characteristics varied by site (Table).

To ensure that the program was consistently implemented at each site, several standard definitions and formulas were developed. The investigators defined 34 PIMs and classes to avoid in adults aged ≥ 65 years regardless of diseases or conditions from the 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.5 However, the Beers List required interpretation on several important points. For example, the Beers List does not advise on how PIMs are to be measured and tracked. Also, it does not specify a goal other than to “improve care of older adults by reducing their exposure to PIMs.”5

Potentially inappropriate medications are now recognized as an important measure by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) and are used as a quality measure in the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). They are typically measured as the number of patients aged ≥ 65 years who received either at least 1 PIM or at least 2 PIMs divided by the total number of patients aged ≥ 65 years during a given period (typically a year). The EQUiPPED program, however, is an intervention targeting providers rather than patients, and for regular monthly feedback, the EQUiPPED team designated its measure as the number of PIMs prescribed to veterans aged ≥ 65 years on discharge from the ED divided by the total number of medications prescribed at discharge in a particular month. Understanding that PIMs are sometimes necessary for treatment, the EQUiPPED team set a goal of reducing PIMs prescribed to below 5% of all discharge medications in the ED.

The EQUiPPED implementation team also operationalized other aspects of the Beers List recommendations. For example, providers are advised that oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should not be prescribed for chronic use “unless other alternatives are not effective and the patient can take a gastroprotective agent.”12 However, there is no guidance on the meaning of chronic use or on dosages. The team determined that the best operational definition of chronic NSAID use for EQUiPPED was prescription duration of ≥ 30 days.

To carry out the intervention, each EQUiPPED site used a letter from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care designating the analysis of outcomes data related to the intervention as an operational activity rather than as research. The EQUiPPED team developed pharmacy quick-order sets in dialogue with ED providers and clinical pharmacists. Clinical applications coordinators facilitated local integration of order sets into the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Local clinical experts reviewed the order sets (eg, the Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee, the Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee, and the Chief of Pharmacy Service) before implementation.

Once the order sets were implemented, the sites began educating providers about the order sets along with the information about Beers List medications. As soon as possible, usually 1 month after the educational sessions, the sites began evaluating data from the local corporate data warehouse regarding medications prescribed in order to calculate monthly PIM rates. Each provider received a report that showed their PIM rate and overall prescribing in the previous month and benchmarked this performance in relation to anonymized peers. The first feedback session was given in person by a physician or a physician-pharmacist team. All sites followed these standard EQUiPPED procedures.

Site Innovations and Adaptations

The Durham site developed a Beers List look-up tool to streamline the calculation of PIMs per provider every month and ensure the systematization of procedures. Although each site introduced education, order sets, and feedback in the same order, launch times differed. Varying levels of staff availability and expertise resulted in order-set rollout times that ranged from 3 weeks to 12 months. Some sites launched additional tools. For example, Durham, Atlanta, and Bronx added blue line alerts, a noninterruptive informational message in CPRS for every Beers List drug prescribed at their VA that warned prescribers to “use with caution in patients 65+.”

Some sites physically placed caution cards on the edge of ED computer screens listing the top 5 PIMS drugs at that site. Nashville, Birmingham, and Durham’s order sets included links to external sites, such as the World Health Organization analgesic ladder and to narcotics equivalency tables to simplify pain management. Nashville ED providers requested e-mail attachments of Beers List drugs, Beers alternatives, and reminders with monthly feedback reports.

Other differences depended on the makeup of the EQUiPPED intervention team and the patient population at each site. A physician champion within the ED, a geriatrician, and a geriatric pharmacist directed the lead Atlanta site. In contrast, a geriatrician led the Durham project and used incentives to help encourage ED provider participation. All Durham ED providers who participated in the program received laminated Beers pocket cards, a printed guide to download the Geriatrics at Your Fingertips app, and a gift card to purchase the app. Other sites distributed some of these materials but did not include the gift card.

Durham-trained resident physicians rotated through the ED each month, as did Atlanta’s. Durham also introduced pre- and posttraining quizzes for resident physicians to test knowledge gained.13 No other site followed this pattern. Differences in local formularies, priorities, patient groups, and preferences led sites to select different order sets for presentation and to adapt them if needed.

Tennessee Valley posted the largest array of order sets in the CPRS with 42 different medication order sets, Atlanta and Birmingham had 12 order sets, and Bronx used the fewest at 3. Durham chose to implement its order sets progressively, with an initial 3, then an additional 2, and then an additional 2. Durham sought feedback from providers during this staged rollout and incorporated changes into the development of the next set. Birmingham and Bronx began tracking use of order sets electronically. The Atlanta site conducted qualitative interviews with a subset of providers (both untrained and trained) to evaluate usage patterns. Nashville used the geriatric order sets as a template to develop order sets for other emergency conditions.

Implementation Model

By understanding practice variations and similarities at a heterogeneous group of VA hospitals, tracking prescribing data, and conducting a thematic content analysis of field reports from EQUiPPED sites, the investigators were able to develop a relatively standardized process model to improve ED prescribing practices for clinicians caring for older adults. The implementation model captures factors at the level of context (alignment with priorities of care), inputs (resources available), outputs (activities and participation), and outcomes (short, medium, and long-term). In addition to the process model, EQUiPPED has developed an implementation tool kit, which includes order set logic, the Beers look-up tool developed by Durham, education materials, and provider feedback templates.

The implementation model and components of the tool kit are available by request through the Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC. With these materials, the EQUiPPED project is poised for implementation at other VA EDs or at sites beyond the VA.

Conclusion

Successful implementation of EQUiPPED, an innovative geriatric practice intervention to reduce PIM prescribing in the ED, is dependent on careful planning and site customization. Distilling factors that differed across VA sites resulted in a model intended to promote implementation and dissemination of the EQUIPPED intervention.

Suboptimal prescribing for older adults discharged from the emergency department (ED) is a recognized problem.1-4 At the Durham VAMC in North Carolina, for example, suboptimal prescribing was tracked in about 30% of patients discharged from the ED; 34% experienced an adverse medical event within 90 days, including repeated ED visits, hospitalization, or death.4

In 2012, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) issued its Beers Criteria list of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to avoid (updated again in 2015).5,6 As EDs are not suited to meet the needs of a vulnerable population with complex medical conditions and medication regimens, putting these evidence-based guidelines into practice represented both a challenge and an opportunity.7

In 2013, an investigator from the Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) teamed up with an internist at the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia to expand a local quality improvement intervention to reduce the use of PIMs prescribed to veterans at time of discharge from the ED. The project received funding from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Transforming VA Healthcare for the 21st Century (T-21) initiative for a 3-site quality improvement project. In the second year, the project was expanded to 5 sites representing a collaboration of 4 different GRECCs.

With a common mission to develop and evaluate new models of geriatric care for veterans, GRECCs offer a national network for rapid implementation and potential dissemination of innovative clinical demonstration projects. Preliminary evaluation showed a significant and sustained reduction of ED-prescribed PIMs at the first implementation site, with favorable results suggested by subsequent sites.8,9

These results demonstrated success despite implementation challenges, including creating order sets and educating clinicians to change behavior. This article describes common and diverging factors across 5 implementation sites and presents an implementation process model that was developed by examining these factors.

Implementation

Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Dis-charged from the ED (EQUiPPED) is a multicomponent, interdisciplinaryquality-improvement initiative to reduce PIMs. The program imple-mented 3 evidence-based inter-ventions: (1) ED provider education; (2) clinical decision support in the form of pharmacy quick-order sets; and (3) individual provider academic detailing, audit and feedback, and peer benchmarking. 10,11

The original implementation sites in September 2013 were the Atlanta VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC), the Durham VAMC (Durham GRECC), and the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System Nashville Campus (Tennessee Valley GRECC). In September 2014 the James J. Peters VAMC (Bronx GRECC) and the Birmingham VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC) also were included. Provider characteristics varied by site (Table).

To ensure that the program was consistently implemented at each site, several standard definitions and formulas were developed. The investigators defined 34 PIMs and classes to avoid in adults aged ≥ 65 years regardless of diseases or conditions from the 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.5 However, the Beers List required interpretation on several important points. For example, the Beers List does not advise on how PIMs are to be measured and tracked. Also, it does not specify a goal other than to “improve care of older adults by reducing their exposure to PIMs.”5

Potentially inappropriate medications are now recognized as an important measure by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) and are used as a quality measure in the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). They are typically measured as the number of patients aged ≥ 65 years who received either at least 1 PIM or at least 2 PIMs divided by the total number of patients aged ≥ 65 years during a given period (typically a year). The EQUiPPED program, however, is an intervention targeting providers rather than patients, and for regular monthly feedback, the EQUiPPED team designated its measure as the number of PIMs prescribed to veterans aged ≥ 65 years on discharge from the ED divided by the total number of medications prescribed at discharge in a particular month. Understanding that PIMs are sometimes necessary for treatment, the EQUiPPED team set a goal of reducing PIMs prescribed to below 5% of all discharge medications in the ED.

The EQUiPPED implementation team also operationalized other aspects of the Beers List recommendations. For example, providers are advised that oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should not be prescribed for chronic use “unless other alternatives are not effective and the patient can take a gastroprotective agent.”12 However, there is no guidance on the meaning of chronic use or on dosages. The team determined that the best operational definition of chronic NSAID use for EQUiPPED was prescription duration of ≥ 30 days.

To carry out the intervention, each EQUiPPED site used a letter from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care designating the analysis of outcomes data related to the intervention as an operational activity rather than as research. The EQUiPPED team developed pharmacy quick-order sets in dialogue with ED providers and clinical pharmacists. Clinical applications coordinators facilitated local integration of order sets into the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Local clinical experts reviewed the order sets (eg, the Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee, the Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee, and the Chief of Pharmacy Service) before implementation.

Once the order sets were implemented, the sites began educating providers about the order sets along with the information about Beers List medications. As soon as possible, usually 1 month after the educational sessions, the sites began evaluating data from the local corporate data warehouse regarding medications prescribed in order to calculate monthly PIM rates. Each provider received a report that showed their PIM rate and overall prescribing in the previous month and benchmarked this performance in relation to anonymized peers. The first feedback session was given in person by a physician or a physician-pharmacist team. All sites followed these standard EQUiPPED procedures.

Site Innovations and Adaptations

The Durham site developed a Beers List look-up tool to streamline the calculation of PIMs per provider every month and ensure the systematization of procedures. Although each site introduced education, order sets, and feedback in the same order, launch times differed. Varying levels of staff availability and expertise resulted in order-set rollout times that ranged from 3 weeks to 12 months. Some sites launched additional tools. For example, Durham, Atlanta, and Bronx added blue line alerts, a noninterruptive informational message in CPRS for every Beers List drug prescribed at their VA that warned prescribers to “use with caution in patients 65+.”

Some sites physically placed caution cards on the edge of ED computer screens listing the top 5 PIMS drugs at that site. Nashville, Birmingham, and Durham’s order sets included links to external sites, such as the World Health Organization analgesic ladder and to narcotics equivalency tables to simplify pain management. Nashville ED providers requested e-mail attachments of Beers List drugs, Beers alternatives, and reminders with monthly feedback reports.

Other differences depended on the makeup of the EQUiPPED intervention team and the patient population at each site. A physician champion within the ED, a geriatrician, and a geriatric pharmacist directed the lead Atlanta site. In contrast, a geriatrician led the Durham project and used incentives to help encourage ED provider participation. All Durham ED providers who participated in the program received laminated Beers pocket cards, a printed guide to download the Geriatrics at Your Fingertips app, and a gift card to purchase the app. Other sites distributed some of these materials but did not include the gift card.

Durham-trained resident physicians rotated through the ED each month, as did Atlanta’s. Durham also introduced pre- and posttraining quizzes for resident physicians to test knowledge gained.13 No other site followed this pattern. Differences in local formularies, priorities, patient groups, and preferences led sites to select different order sets for presentation and to adapt them if needed.

Tennessee Valley posted the largest array of order sets in the CPRS with 42 different medication order sets, Atlanta and Birmingham had 12 order sets, and Bronx used the fewest at 3. Durham chose to implement its order sets progressively, with an initial 3, then an additional 2, and then an additional 2. Durham sought feedback from providers during this staged rollout and incorporated changes into the development of the next set. Birmingham and Bronx began tracking use of order sets electronically. The Atlanta site conducted qualitative interviews with a subset of providers (both untrained and trained) to evaluate usage patterns. Nashville used the geriatric order sets as a template to develop order sets for other emergency conditions.

Implementation Model

By understanding practice variations and similarities at a heterogeneous group of VA hospitals, tracking prescribing data, and conducting a thematic content analysis of field reports from EQUiPPED sites, the investigators were able to develop a relatively standardized process model to improve ED prescribing practices for clinicians caring for older adults. The implementation model captures factors at the level of context (alignment with priorities of care), inputs (resources available), outputs (activities and participation), and outcomes (short, medium, and long-term). In addition to the process model, EQUiPPED has developed an implementation tool kit, which includes order set logic, the Beers look-up tool developed by Durham, education materials, and provider feedback templates.

The implementation model and components of the tool kit are available by request through the Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC. With these materials, the EQUiPPED project is poised for implementation at other VA EDs or at sites beyond the VA.

Conclusion

Successful implementation of EQUiPPED, an innovative geriatric practice intervention to reduce PIM prescribing in the ED, is dependent on careful planning and site customization. Distilling factors that differed across VA sites resulted in a model intended to promote implementation and dissemination of the EQUIPPED intervention.

1. Beers MH, Storrie M, Lee G. Potential adverse drug interactions in the emergency room: an issue in the quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(1):61-64.

2. Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, et al. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(12):1232-1242.

3. Hustey FM, Wallis N, Miller J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):804-807.

4. Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, et al. Quality of pharmacotherapy and outcomes for older veterans discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):875-880.

5. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

7. Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2116-2121.

8. Stevens MB, Hastings SN, Powers J, et al. Enhancing the Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department (EQUiPPED): preliminary results from Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department, a novel multicomponent interdisciplinary quality improvement initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):1025-1029.

9. Moss JM, Bryan WE, Wilkerson LM, et al. Impact of clinical pharmacy specialists on the design and implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease inappropriate medications in a Veterans Affairs emergency deepartment. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(1):74-80.

10. O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409.

11. Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Dexter PR, Hui SL, Callahan CM, Miller DK. Computerized decision support to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing to older emergency department patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1388-1394.

12. The American Geriatrics Association. A Pocket Guide to the AGS Beers Criteria. New York, NY: The American Geriatrics Association; 2012.

13. Wilkerson LM, Owenby R, Bryan W, et al. An interdisciplinary academic detailing approach to decrease inappropriate medication prescribing for older veterans treated in the Emergency Department. In: Proceeding from the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting; May 14-17, 2015; National Harbor, MD. Abstract B67.

1. Beers MH, Storrie M, Lee G. Potential adverse drug interactions in the emergency room: an issue in the quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(1):61-64.

2. Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, et al. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(12):1232-1242.

3. Hustey FM, Wallis N, Miller J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):804-807.

4. Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, et al. Quality of pharmacotherapy and outcomes for older veterans discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):875-880.

5. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

7. Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2116-2121.

8. Stevens MB, Hastings SN, Powers J, et al. Enhancing the Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department (EQUiPPED): preliminary results from Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department, a novel multicomponent interdisciplinary quality improvement initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):1025-1029.

9. Moss JM, Bryan WE, Wilkerson LM, et al. Impact of clinical pharmacy specialists on the design and implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease inappropriate medications in a Veterans Affairs emergency deepartment. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(1):74-80.

10. O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409.

11. Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Dexter PR, Hui SL, Callahan CM, Miller DK. Computerized decision support to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing to older emergency department patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1388-1394.

12. The American Geriatrics Association. A Pocket Guide to the AGS Beers Criteria. New York, NY: The American Geriatrics Association; 2012.

13. Wilkerson LM, Owenby R, Bryan W, et al. An interdisciplinary academic detailing approach to decrease inappropriate medication prescribing for older veterans treated in the Emergency Department. In: Proceeding from the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting; May 14-17, 2015; National Harbor, MD. Abstract B67.