User login

Implementing the EQUiPPED Medication Management Program

Suboptimal prescribing for older adults discharged from the emergency department (ED) is a recognized problem.1-4 At the Durham VAMC in North Carolina, for example, suboptimal prescribing was tracked in about 30% of patients discharged from the ED; 34% experienced an adverse medical event within 90 days, including repeated ED visits, hospitalization, or death.4

In 2012, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) issued its Beers Criteria list of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to avoid (updated again in 2015).5,6 As EDs are not suited to meet the needs of a vulnerable population with complex medical conditions and medication regimens, putting these evidence-based guidelines into practice represented both a challenge and an opportunity.7

In 2013, an investigator from the Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) teamed up with an internist at the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia to expand a local quality improvement intervention to reduce the use of PIMs prescribed to veterans at time of discharge from the ED. The project received funding from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Transforming VA Healthcare for the 21st Century (T-21) initiative for a 3-site quality improvement project. In the second year, the project was expanded to 5 sites representing a collaboration of 4 different GRECCs.

With a common mission to develop and evaluate new models of geriatric care for veterans, GRECCs offer a national network for rapid implementation and potential dissemination of innovative clinical demonstration projects. Preliminary evaluation showed a significant and sustained reduction of ED-prescribed PIMs at the first implementation site, with favorable results suggested by subsequent sites.8,9

These results demonstrated success despite implementation challenges, including creating order sets and educating clinicians to change behavior. This article describes common and diverging factors across 5 implementation sites and presents an implementation process model that was developed by examining these factors.

Implementation

Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Dis-charged from the ED (EQUiPPED) is a multicomponent, interdisciplinaryquality-improvement initiative to reduce PIMs. The program imple-mented 3 evidence-based inter-ventions: (1) ED provider education; (2) clinical decision support in the form of pharmacy quick-order sets; and (3) individual provider academic detailing, audit and feedback, and peer benchmarking. 10,11

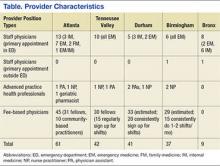

The original implementation sites in September 2013 were the Atlanta VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC), the Durham VAMC (Durham GRECC), and the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System Nashville Campus (Tennessee Valley GRECC). In September 2014 the James J. Peters VAMC (Bronx GRECC) and the Birmingham VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC) also were included. Provider characteristics varied by site (Table).

To ensure that the program was consistently implemented at each site, several standard definitions and formulas were developed. The investigators defined 34 PIMs and classes to avoid in adults aged ≥ 65 years regardless of diseases or conditions from the 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.5 However, the Beers List required interpretation on several important points. For example, the Beers List does not advise on how PIMs are to be measured and tracked. Also, it does not specify a goal other than to “improve care of older adults by reducing their exposure to PIMs.”5

Potentially inappropriate medications are now recognized as an important measure by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) and are used as a quality measure in the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). They are typically measured as the number of patients aged ≥ 65 years who received either at least 1 PIM or at least 2 PIMs divided by the total number of patients aged ≥ 65 years during a given period (typically a year). The EQUiPPED program, however, is an intervention targeting providers rather than patients, and for regular monthly feedback, the EQUiPPED team designated its measure as the number of PIMs prescribed to veterans aged ≥ 65 years on discharge from the ED divided by the total number of medications prescribed at discharge in a particular month. Understanding that PIMs are sometimes necessary for treatment, the EQUiPPED team set a goal of reducing PIMs prescribed to below 5% of all discharge medications in the ED.

The EQUiPPED implementation team also operationalized other aspects of the Beers List recommendations. For example, providers are advised that oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should not be prescribed for chronic use “unless other alternatives are not effective and the patient can take a gastroprotective agent.”12 However, there is no guidance on the meaning of chronic use or on dosages. The team determined that the best operational definition of chronic NSAID use for EQUiPPED was prescription duration of ≥ 30 days.

To carry out the intervention, each EQUiPPED site used a letter from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care designating the analysis of outcomes data related to the intervention as an operational activity rather than as research. The EQUiPPED team developed pharmacy quick-order sets in dialogue with ED providers and clinical pharmacists. Clinical applications coordinators facilitated local integration of order sets into the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Local clinical experts reviewed the order sets (eg, the Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee, the Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee, and the Chief of Pharmacy Service) before implementation.

Once the order sets were implemented, the sites began educating providers about the order sets along with the information about Beers List medications. As soon as possible, usually 1 month after the educational sessions, the sites began evaluating data from the local corporate data warehouse regarding medications prescribed in order to calculate monthly PIM rates. Each provider received a report that showed their PIM rate and overall prescribing in the previous month and benchmarked this performance in relation to anonymized peers. The first feedback session was given in person by a physician or a physician-pharmacist team. All sites followed these standard EQUiPPED procedures.

Site Innovations and Adaptations

The Durham site developed a Beers List look-up tool to streamline the calculation of PIMs per provider every month and ensure the systematization of procedures. Although each site introduced education, order sets, and feedback in the same order, launch times differed. Varying levels of staff availability and expertise resulted in order-set rollout times that ranged from 3 weeks to 12 months. Some sites launched additional tools. For example, Durham, Atlanta, and Bronx added blue line alerts, a noninterruptive informational message in CPRS for every Beers List drug prescribed at their VA that warned prescribers to “use with caution in patients 65+.”

Some sites physically placed caution cards on the edge of ED computer screens listing the top 5 PIMS drugs at that site. Nashville, Birmingham, and Durham’s order sets included links to external sites, such as the World Health Organization analgesic ladder and to narcotics equivalency tables to simplify pain management. Nashville ED providers requested e-mail attachments of Beers List drugs, Beers alternatives, and reminders with monthly feedback reports.

Other differences depended on the makeup of the EQUiPPED intervention team and the patient population at each site. A physician champion within the ED, a geriatrician, and a geriatric pharmacist directed the lead Atlanta site. In contrast, a geriatrician led the Durham project and used incentives to help encourage ED provider participation. All Durham ED providers who participated in the program received laminated Beers pocket cards, a printed guide to download the Geriatrics at Your Fingertips app, and a gift card to purchase the app. Other sites distributed some of these materials but did not include the gift card.

Durham-trained resident physicians rotated through the ED each month, as did Atlanta’s. Durham also introduced pre- and posttraining quizzes for resident physicians to test knowledge gained.13 No other site followed this pattern. Differences in local formularies, priorities, patient groups, and preferences led sites to select different order sets for presentation and to adapt them if needed.

Tennessee Valley posted the largest array of order sets in the CPRS with 42 different medication order sets, Atlanta and Birmingham had 12 order sets, and Bronx used the fewest at 3. Durham chose to implement its order sets progressively, with an initial 3, then an additional 2, and then an additional 2. Durham sought feedback from providers during this staged rollout and incorporated changes into the development of the next set. Birmingham and Bronx began tracking use of order sets electronically. The Atlanta site conducted qualitative interviews with a subset of providers (both untrained and trained) to evaluate usage patterns. Nashville used the geriatric order sets as a template to develop order sets for other emergency conditions.

Implementation Model

By understanding practice variations and similarities at a heterogeneous group of VA hospitals, tracking prescribing data, and conducting a thematic content analysis of field reports from EQUiPPED sites, the investigators were able to develop a relatively standardized process model to improve ED prescribing practices for clinicians caring for older adults. The implementation model captures factors at the level of context (alignment with priorities of care), inputs (resources available), outputs (activities and participation), and outcomes (short, medium, and long-term). In addition to the process model, EQUiPPED has developed an implementation tool kit, which includes order set logic, the Beers look-up tool developed by Durham, education materials, and provider feedback templates.

The implementation model and components of the tool kit are available by request through the Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC. With these materials, the EQUiPPED project is poised for implementation at other VA EDs or at sites beyond the VA.

Conclusion

Successful implementation of EQUiPPED, an innovative geriatric practice intervention to reduce PIM prescribing in the ED, is dependent on careful planning and site customization. Distilling factors that differed across VA sites resulted in a model intended to promote implementation and dissemination of the EQUIPPED intervention.

1. Beers MH, Storrie M, Lee G. Potential adverse drug interactions in the emergency room: an issue in the quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(1):61-64.

2. Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, et al. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(12):1232-1242.

3. Hustey FM, Wallis N, Miller J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):804-807.

4. Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, et al. Quality of pharmacotherapy and outcomes for older veterans discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):875-880.

5. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

7. Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2116-2121.

8. Stevens MB, Hastings SN, Powers J, et al. Enhancing the Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department (EQUiPPED): preliminary results from Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department, a novel multicomponent interdisciplinary quality improvement initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):1025-1029.

9. Moss JM, Bryan WE, Wilkerson LM, et al. Impact of clinical pharmacy specialists on the design and implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease inappropriate medications in a Veterans Affairs emergency deepartment. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(1):74-80.

10. O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409.

11. Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Dexter PR, Hui SL, Callahan CM, Miller DK. Computerized decision support to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing to older emergency department patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1388-1394.

12. The American Geriatrics Association. A Pocket Guide to the AGS Beers Criteria. New York, NY: The American Geriatrics Association; 2012.

13. Wilkerson LM, Owenby R, Bryan W, et al. An interdisciplinary academic detailing approach to decrease inappropriate medication prescribing for older veterans treated in the Emergency Department. In: Proceeding from the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting; May 14-17, 2015; National Harbor, MD. Abstract B67.

Suboptimal prescribing for older adults discharged from the emergency department (ED) is a recognized problem.1-4 At the Durham VAMC in North Carolina, for example, suboptimal prescribing was tracked in about 30% of patients discharged from the ED; 34% experienced an adverse medical event within 90 days, including repeated ED visits, hospitalization, or death.4

In 2012, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) issued its Beers Criteria list of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to avoid (updated again in 2015).5,6 As EDs are not suited to meet the needs of a vulnerable population with complex medical conditions and medication regimens, putting these evidence-based guidelines into practice represented both a challenge and an opportunity.7

In 2013, an investigator from the Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) teamed up with an internist at the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia to expand a local quality improvement intervention to reduce the use of PIMs prescribed to veterans at time of discharge from the ED. The project received funding from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Transforming VA Healthcare for the 21st Century (T-21) initiative for a 3-site quality improvement project. In the second year, the project was expanded to 5 sites representing a collaboration of 4 different GRECCs.

With a common mission to develop and evaluate new models of geriatric care for veterans, GRECCs offer a national network for rapid implementation and potential dissemination of innovative clinical demonstration projects. Preliminary evaluation showed a significant and sustained reduction of ED-prescribed PIMs at the first implementation site, with favorable results suggested by subsequent sites.8,9

These results demonstrated success despite implementation challenges, including creating order sets and educating clinicians to change behavior. This article describes common and diverging factors across 5 implementation sites and presents an implementation process model that was developed by examining these factors.

Implementation

Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Dis-charged from the ED (EQUiPPED) is a multicomponent, interdisciplinaryquality-improvement initiative to reduce PIMs. The program imple-mented 3 evidence-based inter-ventions: (1) ED provider education; (2) clinical decision support in the form of pharmacy quick-order sets; and (3) individual provider academic detailing, audit and feedback, and peer benchmarking. 10,11

The original implementation sites in September 2013 were the Atlanta VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC), the Durham VAMC (Durham GRECC), and the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System Nashville Campus (Tennessee Valley GRECC). In September 2014 the James J. Peters VAMC (Bronx GRECC) and the Birmingham VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC) also were included. Provider characteristics varied by site (Table).

To ensure that the program was consistently implemented at each site, several standard definitions and formulas were developed. The investigators defined 34 PIMs and classes to avoid in adults aged ≥ 65 years regardless of diseases or conditions from the 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.5 However, the Beers List required interpretation on several important points. For example, the Beers List does not advise on how PIMs are to be measured and tracked. Also, it does not specify a goal other than to “improve care of older adults by reducing their exposure to PIMs.”5

Potentially inappropriate medications are now recognized as an important measure by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) and are used as a quality measure in the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). They are typically measured as the number of patients aged ≥ 65 years who received either at least 1 PIM or at least 2 PIMs divided by the total number of patients aged ≥ 65 years during a given period (typically a year). The EQUiPPED program, however, is an intervention targeting providers rather than patients, and for regular monthly feedback, the EQUiPPED team designated its measure as the number of PIMs prescribed to veterans aged ≥ 65 years on discharge from the ED divided by the total number of medications prescribed at discharge in a particular month. Understanding that PIMs are sometimes necessary for treatment, the EQUiPPED team set a goal of reducing PIMs prescribed to below 5% of all discharge medications in the ED.

The EQUiPPED implementation team also operationalized other aspects of the Beers List recommendations. For example, providers are advised that oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should not be prescribed for chronic use “unless other alternatives are not effective and the patient can take a gastroprotective agent.”12 However, there is no guidance on the meaning of chronic use or on dosages. The team determined that the best operational definition of chronic NSAID use for EQUiPPED was prescription duration of ≥ 30 days.

To carry out the intervention, each EQUiPPED site used a letter from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care designating the analysis of outcomes data related to the intervention as an operational activity rather than as research. The EQUiPPED team developed pharmacy quick-order sets in dialogue with ED providers and clinical pharmacists. Clinical applications coordinators facilitated local integration of order sets into the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Local clinical experts reviewed the order sets (eg, the Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee, the Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee, and the Chief of Pharmacy Service) before implementation.

Once the order sets were implemented, the sites began educating providers about the order sets along with the information about Beers List medications. As soon as possible, usually 1 month after the educational sessions, the sites began evaluating data from the local corporate data warehouse regarding medications prescribed in order to calculate monthly PIM rates. Each provider received a report that showed their PIM rate and overall prescribing in the previous month and benchmarked this performance in relation to anonymized peers. The first feedback session was given in person by a physician or a physician-pharmacist team. All sites followed these standard EQUiPPED procedures.

Site Innovations and Adaptations

The Durham site developed a Beers List look-up tool to streamline the calculation of PIMs per provider every month and ensure the systematization of procedures. Although each site introduced education, order sets, and feedback in the same order, launch times differed. Varying levels of staff availability and expertise resulted in order-set rollout times that ranged from 3 weeks to 12 months. Some sites launched additional tools. For example, Durham, Atlanta, and Bronx added blue line alerts, a noninterruptive informational message in CPRS for every Beers List drug prescribed at their VA that warned prescribers to “use with caution in patients 65+.”

Some sites physically placed caution cards on the edge of ED computer screens listing the top 5 PIMS drugs at that site. Nashville, Birmingham, and Durham’s order sets included links to external sites, such as the World Health Organization analgesic ladder and to narcotics equivalency tables to simplify pain management. Nashville ED providers requested e-mail attachments of Beers List drugs, Beers alternatives, and reminders with monthly feedback reports.

Other differences depended on the makeup of the EQUiPPED intervention team and the patient population at each site. A physician champion within the ED, a geriatrician, and a geriatric pharmacist directed the lead Atlanta site. In contrast, a geriatrician led the Durham project and used incentives to help encourage ED provider participation. All Durham ED providers who participated in the program received laminated Beers pocket cards, a printed guide to download the Geriatrics at Your Fingertips app, and a gift card to purchase the app. Other sites distributed some of these materials but did not include the gift card.

Durham-trained resident physicians rotated through the ED each month, as did Atlanta’s. Durham also introduced pre- and posttraining quizzes for resident physicians to test knowledge gained.13 No other site followed this pattern. Differences in local formularies, priorities, patient groups, and preferences led sites to select different order sets for presentation and to adapt them if needed.

Tennessee Valley posted the largest array of order sets in the CPRS with 42 different medication order sets, Atlanta and Birmingham had 12 order sets, and Bronx used the fewest at 3. Durham chose to implement its order sets progressively, with an initial 3, then an additional 2, and then an additional 2. Durham sought feedback from providers during this staged rollout and incorporated changes into the development of the next set. Birmingham and Bronx began tracking use of order sets electronically. The Atlanta site conducted qualitative interviews with a subset of providers (both untrained and trained) to evaluate usage patterns. Nashville used the geriatric order sets as a template to develop order sets for other emergency conditions.

Implementation Model

By understanding practice variations and similarities at a heterogeneous group of VA hospitals, tracking prescribing data, and conducting a thematic content analysis of field reports from EQUiPPED sites, the investigators were able to develop a relatively standardized process model to improve ED prescribing practices for clinicians caring for older adults. The implementation model captures factors at the level of context (alignment with priorities of care), inputs (resources available), outputs (activities and participation), and outcomes (short, medium, and long-term). In addition to the process model, EQUiPPED has developed an implementation tool kit, which includes order set logic, the Beers look-up tool developed by Durham, education materials, and provider feedback templates.

The implementation model and components of the tool kit are available by request through the Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC. With these materials, the EQUiPPED project is poised for implementation at other VA EDs or at sites beyond the VA.

Conclusion

Successful implementation of EQUiPPED, an innovative geriatric practice intervention to reduce PIM prescribing in the ED, is dependent on careful planning and site customization. Distilling factors that differed across VA sites resulted in a model intended to promote implementation and dissemination of the EQUIPPED intervention.

Suboptimal prescribing for older adults discharged from the emergency department (ED) is a recognized problem.1-4 At the Durham VAMC in North Carolina, for example, suboptimal prescribing was tracked in about 30% of patients discharged from the ED; 34% experienced an adverse medical event within 90 days, including repeated ED visits, hospitalization, or death.4

In 2012, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) issued its Beers Criteria list of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to avoid (updated again in 2015).5,6 As EDs are not suited to meet the needs of a vulnerable population with complex medical conditions and medication regimens, putting these evidence-based guidelines into practice represented both a challenge and an opportunity.7

In 2013, an investigator from the Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) teamed up with an internist at the Atlanta VAMC in Georgia to expand a local quality improvement intervention to reduce the use of PIMs prescribed to veterans at time of discharge from the ED. The project received funding from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Transforming VA Healthcare for the 21st Century (T-21) initiative for a 3-site quality improvement project. In the second year, the project was expanded to 5 sites representing a collaboration of 4 different GRECCs.

With a common mission to develop and evaluate new models of geriatric care for veterans, GRECCs offer a national network for rapid implementation and potential dissemination of innovative clinical demonstration projects. Preliminary evaluation showed a significant and sustained reduction of ED-prescribed PIMs at the first implementation site, with favorable results suggested by subsequent sites.8,9

These results demonstrated success despite implementation challenges, including creating order sets and educating clinicians to change behavior. This article describes common and diverging factors across 5 implementation sites and presents an implementation process model that was developed by examining these factors.

Implementation

Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Dis-charged from the ED (EQUiPPED) is a multicomponent, interdisciplinaryquality-improvement initiative to reduce PIMs. The program imple-mented 3 evidence-based inter-ventions: (1) ED provider education; (2) clinical decision support in the form of pharmacy quick-order sets; and (3) individual provider academic detailing, audit and feedback, and peer benchmarking. 10,11

The original implementation sites in September 2013 were the Atlanta VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC), the Durham VAMC (Durham GRECC), and the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System Nashville Campus (Tennessee Valley GRECC). In September 2014 the James J. Peters VAMC (Bronx GRECC) and the Birmingham VAMC (Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC) also were included. Provider characteristics varied by site (Table).

To ensure that the program was consistently implemented at each site, several standard definitions and formulas were developed. The investigators defined 34 PIMs and classes to avoid in adults aged ≥ 65 years regardless of diseases or conditions from the 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.5 However, the Beers List required interpretation on several important points. For example, the Beers List does not advise on how PIMs are to be measured and tracked. Also, it does not specify a goal other than to “improve care of older adults by reducing their exposure to PIMs.”5

Potentially inappropriate medications are now recognized as an important measure by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) and are used as a quality measure in the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). They are typically measured as the number of patients aged ≥ 65 years who received either at least 1 PIM or at least 2 PIMs divided by the total number of patients aged ≥ 65 years during a given period (typically a year). The EQUiPPED program, however, is an intervention targeting providers rather than patients, and for regular monthly feedback, the EQUiPPED team designated its measure as the number of PIMs prescribed to veterans aged ≥ 65 years on discharge from the ED divided by the total number of medications prescribed at discharge in a particular month. Understanding that PIMs are sometimes necessary for treatment, the EQUiPPED team set a goal of reducing PIMs prescribed to below 5% of all discharge medications in the ED.

The EQUiPPED implementation team also operationalized other aspects of the Beers List recommendations. For example, providers are advised that oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should not be prescribed for chronic use “unless other alternatives are not effective and the patient can take a gastroprotective agent.”12 However, there is no guidance on the meaning of chronic use or on dosages. The team determined that the best operational definition of chronic NSAID use for EQUiPPED was prescription duration of ≥ 30 days.

To carry out the intervention, each EQUiPPED site used a letter from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care designating the analysis of outcomes data related to the intervention as an operational activity rather than as research. The EQUiPPED team developed pharmacy quick-order sets in dialogue with ED providers and clinical pharmacists. Clinical applications coordinators facilitated local integration of order sets into the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Local clinical experts reviewed the order sets (eg, the Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee, the Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee, and the Chief of Pharmacy Service) before implementation.

Once the order sets were implemented, the sites began educating providers about the order sets along with the information about Beers List medications. As soon as possible, usually 1 month after the educational sessions, the sites began evaluating data from the local corporate data warehouse regarding medications prescribed in order to calculate monthly PIM rates. Each provider received a report that showed their PIM rate and overall prescribing in the previous month and benchmarked this performance in relation to anonymized peers. The first feedback session was given in person by a physician or a physician-pharmacist team. All sites followed these standard EQUiPPED procedures.

Site Innovations and Adaptations

The Durham site developed a Beers List look-up tool to streamline the calculation of PIMs per provider every month and ensure the systematization of procedures. Although each site introduced education, order sets, and feedback in the same order, launch times differed. Varying levels of staff availability and expertise resulted in order-set rollout times that ranged from 3 weeks to 12 months. Some sites launched additional tools. For example, Durham, Atlanta, and Bronx added blue line alerts, a noninterruptive informational message in CPRS for every Beers List drug prescribed at their VA that warned prescribers to “use with caution in patients 65+.”

Some sites physically placed caution cards on the edge of ED computer screens listing the top 5 PIMS drugs at that site. Nashville, Birmingham, and Durham’s order sets included links to external sites, such as the World Health Organization analgesic ladder and to narcotics equivalency tables to simplify pain management. Nashville ED providers requested e-mail attachments of Beers List drugs, Beers alternatives, and reminders with monthly feedback reports.

Other differences depended on the makeup of the EQUiPPED intervention team and the patient population at each site. A physician champion within the ED, a geriatrician, and a geriatric pharmacist directed the lead Atlanta site. In contrast, a geriatrician led the Durham project and used incentives to help encourage ED provider participation. All Durham ED providers who participated in the program received laminated Beers pocket cards, a printed guide to download the Geriatrics at Your Fingertips app, and a gift card to purchase the app. Other sites distributed some of these materials but did not include the gift card.

Durham-trained resident physicians rotated through the ED each month, as did Atlanta’s. Durham also introduced pre- and posttraining quizzes for resident physicians to test knowledge gained.13 No other site followed this pattern. Differences in local formularies, priorities, patient groups, and preferences led sites to select different order sets for presentation and to adapt them if needed.

Tennessee Valley posted the largest array of order sets in the CPRS with 42 different medication order sets, Atlanta and Birmingham had 12 order sets, and Bronx used the fewest at 3. Durham chose to implement its order sets progressively, with an initial 3, then an additional 2, and then an additional 2. Durham sought feedback from providers during this staged rollout and incorporated changes into the development of the next set. Birmingham and Bronx began tracking use of order sets electronically. The Atlanta site conducted qualitative interviews with a subset of providers (both untrained and trained) to evaluate usage patterns. Nashville used the geriatric order sets as a template to develop order sets for other emergency conditions.

Implementation Model

By understanding practice variations and similarities at a heterogeneous group of VA hospitals, tracking prescribing data, and conducting a thematic content analysis of field reports from EQUiPPED sites, the investigators were able to develop a relatively standardized process model to improve ED prescribing practices for clinicians caring for older adults. The implementation model captures factors at the level of context (alignment with priorities of care), inputs (resources available), outputs (activities and participation), and outcomes (short, medium, and long-term). In addition to the process model, EQUiPPED has developed an implementation tool kit, which includes order set logic, the Beers look-up tool developed by Durham, education materials, and provider feedback templates.

The implementation model and components of the tool kit are available by request through the Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC. With these materials, the EQUiPPED project is poised for implementation at other VA EDs or at sites beyond the VA.

Conclusion

Successful implementation of EQUiPPED, an innovative geriatric practice intervention to reduce PIM prescribing in the ED, is dependent on careful planning and site customization. Distilling factors that differed across VA sites resulted in a model intended to promote implementation and dissemination of the EQUIPPED intervention.

1. Beers MH, Storrie M, Lee G. Potential adverse drug interactions in the emergency room: an issue in the quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(1):61-64.

2. Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, et al. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(12):1232-1242.

3. Hustey FM, Wallis N, Miller J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):804-807.

4. Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, et al. Quality of pharmacotherapy and outcomes for older veterans discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):875-880.

5. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

7. Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2116-2121.

8. Stevens MB, Hastings SN, Powers J, et al. Enhancing the Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department (EQUiPPED): preliminary results from Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department, a novel multicomponent interdisciplinary quality improvement initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):1025-1029.

9. Moss JM, Bryan WE, Wilkerson LM, et al. Impact of clinical pharmacy specialists on the design and implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease inappropriate medications in a Veterans Affairs emergency deepartment. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(1):74-80.

10. O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409.

11. Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Dexter PR, Hui SL, Callahan CM, Miller DK. Computerized decision support to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing to older emergency department patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1388-1394.

12. The American Geriatrics Association. A Pocket Guide to the AGS Beers Criteria. New York, NY: The American Geriatrics Association; 2012.

13. Wilkerson LM, Owenby R, Bryan W, et al. An interdisciplinary academic detailing approach to decrease inappropriate medication prescribing for older veterans treated in the Emergency Department. In: Proceeding from the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting; May 14-17, 2015; National Harbor, MD. Abstract B67.

1. Beers MH, Storrie M, Lee G. Potential adverse drug interactions in the emergency room: an issue in the quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(1):61-64.

2. Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, et al. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(12):1232-1242.

3. Hustey FM, Wallis N, Miller J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):804-807.

4. Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, et al. Quality of pharmacotherapy and outcomes for older veterans discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):875-880.

5. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

7. Hwang U, Shah MN, Han JH, Carpenter CR, Siu AL, Adams JG. Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(12):2116-2121.

8. Stevens MB, Hastings SN, Powers J, et al. Enhancing the Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department (EQUiPPED): preliminary results from Enhancing Quality of Prescribing Practices for Older Veterans Discharged from the Emergency Department, a novel multicomponent interdisciplinary quality improvement initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):1025-1029.

9. Moss JM, Bryan WE, Wilkerson LM, et al. Impact of clinical pharmacy specialists on the design and implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease inappropriate medications in a Veterans Affairs emergency deepartment. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(1):74-80.

10. O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409.

11. Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Dexter PR, Hui SL, Callahan CM, Miller DK. Computerized decision support to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing to older emergency department patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1388-1394.

12. The American Geriatrics Association. A Pocket Guide to the AGS Beers Criteria. New York, NY: The American Geriatrics Association; 2012.

13. Wilkerson LM, Owenby R, Bryan W, et al. An interdisciplinary academic detailing approach to decrease inappropriate medication prescribing for older veterans treated in the Emergency Department. In: Proceeding from the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting; May 14-17, 2015; National Harbor, MD. Abstract B67.

Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders: Can We IMPROVE Outcomes?

Investigators at the Atlanta site of the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research and Education Clinical Center (GRECC) developed the Integrated Management and Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders (IMPROVE) clinical demonstration project to enhance medication management and quality of prescribing for vulnerable older veterans. Poor quality prescribing in older adults is common and can result in adverse drug reactions (ADRs); increased emergency department, hospital, and primary care provider (PCP) use; and death. The ADRs alone, which are strongly correlated with multiple medication use, account for at least 10% of hospitalizations in older persons.1

Many factors contributing to poor quality prescribing in older persons include time constraints on health professionals, multiple providers, patient-driven prescribing, patients with low health literacy, and frequent transitions in care between home, hospital, and postacute care. Older veterans may be harmed by taking medications with no clear benefit, duplication of therapy, and omission of beneficial medications. Prescribing medications with known high risk for ADRs, inadequate monitoring, and limited patient education on how and why to take a medication can further increase the risk for adverse outcomes. Prescribing for multimorbid older veterans requires comprehensive, individualized care plans that take into account patients’ goals of care and quality of life, as well as evidence-based practice standards.

Clinical trials have repeatedly shown that individualized pharmacy review can reduce polypharmacy in older patients. Positive outcomes have included reduced ADRs, improved measures of prescribing quality, appropriate medication use, compliance with care recommendations, and reduction in the total number of medications.2-5 Optimal use of medications is achieved when a pharmacist works with other care team members to implement and oversee a care plan, as opposed to each provider working alone.2,5

In 2011, the VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce recommended that facilities offer “individualized pharmacy review for high-risk patients on multiple medications.”6 This recommendation was in line with the increasingly integrated role of the clinical pharmacist in the patient aligned care team (PACT) and the recent requirement that Medicare Part D medication therapy management programs offer this service to select patients with chronic disease.

The IMPROVE Model

Given the high and growing numbers of older veterans enrolled in VA primary care who are at risk for ADRs, the Atlanta VA IMPROVE team implemented a GRECC-funded clinical demonstration project. The project supported the VA’s focus on PACTs in combination with existing best practice standards to improve medication management in high-risk older veterans. The Emory University Institutional Review Board ruled that IMPROVE was a quality improvement project, and therefore was exempt from review and VA research oversight.

For this clinical demonstration, IMPROVE targeted noninstitutionalized veterans aged ≥ 85 years taking 10 or more medications who received care in the VA primary care clinic and used the VA pharmacy for medications. This cohort represented the top 5% of medication users enrolled in the clinic. While age and number of medications are independently associated with increased risk for ADRs, other factors common in this cohort, including higher levels of comorbid disease, frequent care transitions, and cognitive impairment are also associated with higher ADR risk.7The IMPROVE model was designed to promote fully engaged partnerships among veterans, family caregivers, and the PACT with input from all parties in the design of the model. The IMPROVE team conducted individual, qualitative, semistructured interviews with 5 clinical pharmacists, 5 geriatricians, and 1 geriatric nurse practitioner on the challenges faced in the management of medications for older patients, individual needs/barriers to meet these challenges, the clinical pharmacist role in providing recommendations to providers, and attitudes and preferences for team communication.

Challenges discovered included time constraints during clinic visits, a need for joint decision making, and limited competency with principles of health literacy. The IMPROVE team also conducted focus groups with veterans (n = 4) and caregivers (n = 7) to determine medication management needs, values, preferences, and barriers to self-management. Key findings from these sessions included poor recognition of limitations in medication self-management, problems related to health literacy, and misunderstanding the role of the clinical pharmacist.8

Using the information gained from patients, family caregivers, and PACT members, the model was tailored to address concerns. The IMPROVE model engaged a PACT clinical pharmacist skilled in medication management and patient education to perform a face-to-face clinical consult with selected patients and their caregivers.5 Making veterans, families, and PACT members collaborators in IMPROVE’s design helped establish active partnerships that enabled effective execution of the project and promoted sustained culture and system change over time.

Pilot Program

High-risk veterans and their caregivers were recruited by letter, followed by a phone call to schedule an appointment for those interested, and a reminder to bring all their medications to the appointment. Twenty-eight male veterans participated in the pilot. The average age was 89 years; 52% were white; 53% had a diagnosis of dementia; 78% reported assistance with medication management; and patients took an average of 16 medications daily. Recruited high-risk veterans and their caregivers were seen in a 1 hour in-person visit with the clinical pharmacist.

To maximize the benefit of the session, the pharmacist was provided with several tools to assist in a systematic evaluation of medication management concerns and quality of prescribing. Tools included a quick reference card citing potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) per the published 2012 Beers Criteria and a reference for potentially beneficial medications based on the START-STOPP criteria.9,10

A Computerized Patient Record System template was developed to guide the pharmacist visit. The template included medication reconciliation, a systematic review of all medications to verify indication and check for redundancies, drug interactions, PIMs, and proper therapeutic monitoring. The template also included assessments for level of medication assistance available, goals of care, health literacy, and barriers to adherence.

A collaborative review of the medication regimen was conducted with the veteran, caregiver, and pharmacist, resulting in individualized recommendations, education, strategies, and tools to improve the quality and safety of the medication regimen as well as patient adherence. When necessary, pill boxes, illustrated medication schedules, low vision aids, and other adaptive devices were provided.

Communication of recommendations with the PCP occurred by cosignature on the note. Same-day consultation with the PCP was also available for any urgent concerns or significant changes to the regimen. At the discretion of the pharmacist, a face-to-face follow-up visit with the pharmacist or a follow-up phone call was conducted.

Results

Both qualitative and quantitative outcomes measures were used to evaluate the IMPROVE model. Semi-structured postpilot interviews with PCPs showed that the model had high satisfaction, acceptability, and feasibility. Providers reported that the model helped them and their patients in an area that takes considerable time (medication review and education) and is not always feasible in a short clinic visit. Providers were willing to accept pharmacist recommendations, which was likely fostered by pre-intervention strategies to keep communication open about proposed medication changes. In a survey, 93% of patients and caregivers found the IMPROVE model helpful; 100% recommended the clinic to others.

Objective measures found 79% of patients in the pilot had at least 1 medication discontinued, 75% had ≥ 1 dosing or timing adjustments made, and PIMs were reduced 14%. Comparing the 6-month period before the pilot and the 6 months after, pharmacy cost savings averaged $64 per veteran per month. Health care use showed a decreasing trend in phone calls and visits to the PCP.7 Cost savings were comparable or greater than those previously reported for similar interventions.4

Conclusions

The results of the IMPROVE pilot suggest that an integrated model involving both pharmacists and PCPs in managing medications and empowering the patient and family caregivers as stakeholders in their own care can lead to improved quality of medication management and cost savings. Based on the success of the pilot, the IMPROVE model received VA Office of Rural Health funding to translate this model to target rural older veterans in community based outpatient clinics.

The success of the IMPROVE model was undoubtedly enhanced by engaged PACT members at the pilot site and a clinical pharmacist who championed the model. The effort involved in recruiting, scheduling, and assessing participants may limit generalizability to settings without such a champion and without dedicated time available with a pharmacist. Determining which groups of older veterans benefit most from individualized medication management and optimal methods to translate the program to other primary care settings are ongoing endeavors for the Atlanta GRECC IMPROVE team.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a VA Transformation-21 grant awarded through the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care. The authors thank Christine Jasien, MS; for data management, Aaron Bozzorg, MS; for interview transcription, Joette Lowe, PharmD; for general consultation; and the VISN 7 leadership for their support.

1. Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, et al. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):34-41.

2. Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, et al. Effects of geriatric evaluation and management on adverse drug reactions and suboptimal prescribing in the frail elderly. Am J Med. 2004;116(6):394-401.

3. Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, et al. Pharmacist‐led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized, controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing. 2001;30(3):205-211.

4. Chumney EC, Robinson LC. The effects of pharmacist interventions on patients with polypharmacy. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2006;4(3):103-109.

5. Lee JK, Slack MK, Martin J, Ehrman C, Chrisholm-Burns M. Geriatric patient care by U.S. pharmacists in healthcare teams: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1119-1127.

6. Veterans Health Administration Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce. Improving Patient-Centered Medication Management for Elderly Veterans: VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce Report and Recommendations. August 2010.

7. Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet. 2007;370(9582):173-184.

8. Mirk A, Kemp L, Echt KV, Perkins MM. Integrated management and polypharmacy review of vulnerable elders: Can we IMPROVE outcomes? [abstract]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(suppl 1):S92.

9. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-613.

10. Barry P, Gallagher P, Ryan C, O'Mahony D. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)--an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(6):632-638.

Investigators at the Atlanta site of the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research and Education Clinical Center (GRECC) developed the Integrated Management and Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders (IMPROVE) clinical demonstration project to enhance medication management and quality of prescribing for vulnerable older veterans. Poor quality prescribing in older adults is common and can result in adverse drug reactions (ADRs); increased emergency department, hospital, and primary care provider (PCP) use; and death. The ADRs alone, which are strongly correlated with multiple medication use, account for at least 10% of hospitalizations in older persons.1

Many factors contributing to poor quality prescribing in older persons include time constraints on health professionals, multiple providers, patient-driven prescribing, patients with low health literacy, and frequent transitions in care between home, hospital, and postacute care. Older veterans may be harmed by taking medications with no clear benefit, duplication of therapy, and omission of beneficial medications. Prescribing medications with known high risk for ADRs, inadequate monitoring, and limited patient education on how and why to take a medication can further increase the risk for adverse outcomes. Prescribing for multimorbid older veterans requires comprehensive, individualized care plans that take into account patients’ goals of care and quality of life, as well as evidence-based practice standards.

Clinical trials have repeatedly shown that individualized pharmacy review can reduce polypharmacy in older patients. Positive outcomes have included reduced ADRs, improved measures of prescribing quality, appropriate medication use, compliance with care recommendations, and reduction in the total number of medications.2-5 Optimal use of medications is achieved when a pharmacist works with other care team members to implement and oversee a care plan, as opposed to each provider working alone.2,5

In 2011, the VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce recommended that facilities offer “individualized pharmacy review for high-risk patients on multiple medications.”6 This recommendation was in line with the increasingly integrated role of the clinical pharmacist in the patient aligned care team (PACT) and the recent requirement that Medicare Part D medication therapy management programs offer this service to select patients with chronic disease.

The IMPROVE Model

Given the high and growing numbers of older veterans enrolled in VA primary care who are at risk for ADRs, the Atlanta VA IMPROVE team implemented a GRECC-funded clinical demonstration project. The project supported the VA’s focus on PACTs in combination with existing best practice standards to improve medication management in high-risk older veterans. The Emory University Institutional Review Board ruled that IMPROVE was a quality improvement project, and therefore was exempt from review and VA research oversight.

For this clinical demonstration, IMPROVE targeted noninstitutionalized veterans aged ≥ 85 years taking 10 or more medications who received care in the VA primary care clinic and used the VA pharmacy for medications. This cohort represented the top 5% of medication users enrolled in the clinic. While age and number of medications are independently associated with increased risk for ADRs, other factors common in this cohort, including higher levels of comorbid disease, frequent care transitions, and cognitive impairment are also associated with higher ADR risk.7The IMPROVE model was designed to promote fully engaged partnerships among veterans, family caregivers, and the PACT with input from all parties in the design of the model. The IMPROVE team conducted individual, qualitative, semistructured interviews with 5 clinical pharmacists, 5 geriatricians, and 1 geriatric nurse practitioner on the challenges faced in the management of medications for older patients, individual needs/barriers to meet these challenges, the clinical pharmacist role in providing recommendations to providers, and attitudes and preferences for team communication.

Challenges discovered included time constraints during clinic visits, a need for joint decision making, and limited competency with principles of health literacy. The IMPROVE team also conducted focus groups with veterans (n = 4) and caregivers (n = 7) to determine medication management needs, values, preferences, and barriers to self-management. Key findings from these sessions included poor recognition of limitations in medication self-management, problems related to health literacy, and misunderstanding the role of the clinical pharmacist.8

Using the information gained from patients, family caregivers, and PACT members, the model was tailored to address concerns. The IMPROVE model engaged a PACT clinical pharmacist skilled in medication management and patient education to perform a face-to-face clinical consult with selected patients and their caregivers.5 Making veterans, families, and PACT members collaborators in IMPROVE’s design helped establish active partnerships that enabled effective execution of the project and promoted sustained culture and system change over time.

Pilot Program

High-risk veterans and their caregivers were recruited by letter, followed by a phone call to schedule an appointment for those interested, and a reminder to bring all their medications to the appointment. Twenty-eight male veterans participated in the pilot. The average age was 89 years; 52% were white; 53% had a diagnosis of dementia; 78% reported assistance with medication management; and patients took an average of 16 medications daily. Recruited high-risk veterans and their caregivers were seen in a 1 hour in-person visit with the clinical pharmacist.

To maximize the benefit of the session, the pharmacist was provided with several tools to assist in a systematic evaluation of medication management concerns and quality of prescribing. Tools included a quick reference card citing potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) per the published 2012 Beers Criteria and a reference for potentially beneficial medications based on the START-STOPP criteria.9,10

A Computerized Patient Record System template was developed to guide the pharmacist visit. The template included medication reconciliation, a systematic review of all medications to verify indication and check for redundancies, drug interactions, PIMs, and proper therapeutic monitoring. The template also included assessments for level of medication assistance available, goals of care, health literacy, and barriers to adherence.

A collaborative review of the medication regimen was conducted with the veteran, caregiver, and pharmacist, resulting in individualized recommendations, education, strategies, and tools to improve the quality and safety of the medication regimen as well as patient adherence. When necessary, pill boxes, illustrated medication schedules, low vision aids, and other adaptive devices were provided.

Communication of recommendations with the PCP occurred by cosignature on the note. Same-day consultation with the PCP was also available for any urgent concerns or significant changes to the regimen. At the discretion of the pharmacist, a face-to-face follow-up visit with the pharmacist or a follow-up phone call was conducted.

Results

Both qualitative and quantitative outcomes measures were used to evaluate the IMPROVE model. Semi-structured postpilot interviews with PCPs showed that the model had high satisfaction, acceptability, and feasibility. Providers reported that the model helped them and their patients in an area that takes considerable time (medication review and education) and is not always feasible in a short clinic visit. Providers were willing to accept pharmacist recommendations, which was likely fostered by pre-intervention strategies to keep communication open about proposed medication changes. In a survey, 93% of patients and caregivers found the IMPROVE model helpful; 100% recommended the clinic to others.

Objective measures found 79% of patients in the pilot had at least 1 medication discontinued, 75% had ≥ 1 dosing or timing adjustments made, and PIMs were reduced 14%. Comparing the 6-month period before the pilot and the 6 months after, pharmacy cost savings averaged $64 per veteran per month. Health care use showed a decreasing trend in phone calls and visits to the PCP.7 Cost savings were comparable or greater than those previously reported for similar interventions.4

Conclusions

The results of the IMPROVE pilot suggest that an integrated model involving both pharmacists and PCPs in managing medications and empowering the patient and family caregivers as stakeholders in their own care can lead to improved quality of medication management and cost savings. Based on the success of the pilot, the IMPROVE model received VA Office of Rural Health funding to translate this model to target rural older veterans in community based outpatient clinics.

The success of the IMPROVE model was undoubtedly enhanced by engaged PACT members at the pilot site and a clinical pharmacist who championed the model. The effort involved in recruiting, scheduling, and assessing participants may limit generalizability to settings without such a champion and without dedicated time available with a pharmacist. Determining which groups of older veterans benefit most from individualized medication management and optimal methods to translate the program to other primary care settings are ongoing endeavors for the Atlanta GRECC IMPROVE team.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a VA Transformation-21 grant awarded through the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care. The authors thank Christine Jasien, MS; for data management, Aaron Bozzorg, MS; for interview transcription, Joette Lowe, PharmD; for general consultation; and the VISN 7 leadership for their support.

Investigators at the Atlanta site of the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research and Education Clinical Center (GRECC) developed the Integrated Management and Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders (IMPROVE) clinical demonstration project to enhance medication management and quality of prescribing for vulnerable older veterans. Poor quality prescribing in older adults is common and can result in adverse drug reactions (ADRs); increased emergency department, hospital, and primary care provider (PCP) use; and death. The ADRs alone, which are strongly correlated with multiple medication use, account for at least 10% of hospitalizations in older persons.1

Many factors contributing to poor quality prescribing in older persons include time constraints on health professionals, multiple providers, patient-driven prescribing, patients with low health literacy, and frequent transitions in care between home, hospital, and postacute care. Older veterans may be harmed by taking medications with no clear benefit, duplication of therapy, and omission of beneficial medications. Prescribing medications with known high risk for ADRs, inadequate monitoring, and limited patient education on how and why to take a medication can further increase the risk for adverse outcomes. Prescribing for multimorbid older veterans requires comprehensive, individualized care plans that take into account patients’ goals of care and quality of life, as well as evidence-based practice standards.

Clinical trials have repeatedly shown that individualized pharmacy review can reduce polypharmacy in older patients. Positive outcomes have included reduced ADRs, improved measures of prescribing quality, appropriate medication use, compliance with care recommendations, and reduction in the total number of medications.2-5 Optimal use of medications is achieved when a pharmacist works with other care team members to implement and oversee a care plan, as opposed to each provider working alone.2,5

In 2011, the VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce recommended that facilities offer “individualized pharmacy review for high-risk patients on multiple medications.”6 This recommendation was in line with the increasingly integrated role of the clinical pharmacist in the patient aligned care team (PACT) and the recent requirement that Medicare Part D medication therapy management programs offer this service to select patients with chronic disease.

The IMPROVE Model

Given the high and growing numbers of older veterans enrolled in VA primary care who are at risk for ADRs, the Atlanta VA IMPROVE team implemented a GRECC-funded clinical demonstration project. The project supported the VA’s focus on PACTs in combination with existing best practice standards to improve medication management in high-risk older veterans. The Emory University Institutional Review Board ruled that IMPROVE was a quality improvement project, and therefore was exempt from review and VA research oversight.

For this clinical demonstration, IMPROVE targeted noninstitutionalized veterans aged ≥ 85 years taking 10 or more medications who received care in the VA primary care clinic and used the VA pharmacy for medications. This cohort represented the top 5% of medication users enrolled in the clinic. While age and number of medications are independently associated with increased risk for ADRs, other factors common in this cohort, including higher levels of comorbid disease, frequent care transitions, and cognitive impairment are also associated with higher ADR risk.7The IMPROVE model was designed to promote fully engaged partnerships among veterans, family caregivers, and the PACT with input from all parties in the design of the model. The IMPROVE team conducted individual, qualitative, semistructured interviews with 5 clinical pharmacists, 5 geriatricians, and 1 geriatric nurse practitioner on the challenges faced in the management of medications for older patients, individual needs/barriers to meet these challenges, the clinical pharmacist role in providing recommendations to providers, and attitudes and preferences for team communication.

Challenges discovered included time constraints during clinic visits, a need for joint decision making, and limited competency with principles of health literacy. The IMPROVE team also conducted focus groups with veterans (n = 4) and caregivers (n = 7) to determine medication management needs, values, preferences, and barriers to self-management. Key findings from these sessions included poor recognition of limitations in medication self-management, problems related to health literacy, and misunderstanding the role of the clinical pharmacist.8

Using the information gained from patients, family caregivers, and PACT members, the model was tailored to address concerns. The IMPROVE model engaged a PACT clinical pharmacist skilled in medication management and patient education to perform a face-to-face clinical consult with selected patients and their caregivers.5 Making veterans, families, and PACT members collaborators in IMPROVE’s design helped establish active partnerships that enabled effective execution of the project and promoted sustained culture and system change over time.

Pilot Program

High-risk veterans and their caregivers were recruited by letter, followed by a phone call to schedule an appointment for those interested, and a reminder to bring all their medications to the appointment. Twenty-eight male veterans participated in the pilot. The average age was 89 years; 52% were white; 53% had a diagnosis of dementia; 78% reported assistance with medication management; and patients took an average of 16 medications daily. Recruited high-risk veterans and their caregivers were seen in a 1 hour in-person visit with the clinical pharmacist.

To maximize the benefit of the session, the pharmacist was provided with several tools to assist in a systematic evaluation of medication management concerns and quality of prescribing. Tools included a quick reference card citing potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) per the published 2012 Beers Criteria and a reference for potentially beneficial medications based on the START-STOPP criteria.9,10

A Computerized Patient Record System template was developed to guide the pharmacist visit. The template included medication reconciliation, a systematic review of all medications to verify indication and check for redundancies, drug interactions, PIMs, and proper therapeutic monitoring. The template also included assessments for level of medication assistance available, goals of care, health literacy, and barriers to adherence.

A collaborative review of the medication regimen was conducted with the veteran, caregiver, and pharmacist, resulting in individualized recommendations, education, strategies, and tools to improve the quality and safety of the medication regimen as well as patient adherence. When necessary, pill boxes, illustrated medication schedules, low vision aids, and other adaptive devices were provided.

Communication of recommendations with the PCP occurred by cosignature on the note. Same-day consultation with the PCP was also available for any urgent concerns or significant changes to the regimen. At the discretion of the pharmacist, a face-to-face follow-up visit with the pharmacist or a follow-up phone call was conducted.

Results

Both qualitative and quantitative outcomes measures were used to evaluate the IMPROVE model. Semi-structured postpilot interviews with PCPs showed that the model had high satisfaction, acceptability, and feasibility. Providers reported that the model helped them and their patients in an area that takes considerable time (medication review and education) and is not always feasible in a short clinic visit. Providers were willing to accept pharmacist recommendations, which was likely fostered by pre-intervention strategies to keep communication open about proposed medication changes. In a survey, 93% of patients and caregivers found the IMPROVE model helpful; 100% recommended the clinic to others.

Objective measures found 79% of patients in the pilot had at least 1 medication discontinued, 75% had ≥ 1 dosing or timing adjustments made, and PIMs were reduced 14%. Comparing the 6-month period before the pilot and the 6 months after, pharmacy cost savings averaged $64 per veteran per month. Health care use showed a decreasing trend in phone calls and visits to the PCP.7 Cost savings were comparable or greater than those previously reported for similar interventions.4

Conclusions

The results of the IMPROVE pilot suggest that an integrated model involving both pharmacists and PCPs in managing medications and empowering the patient and family caregivers as stakeholders in their own care can lead to improved quality of medication management and cost savings. Based on the success of the pilot, the IMPROVE model received VA Office of Rural Health funding to translate this model to target rural older veterans in community based outpatient clinics.

The success of the IMPROVE model was undoubtedly enhanced by engaged PACT members at the pilot site and a clinical pharmacist who championed the model. The effort involved in recruiting, scheduling, and assessing participants may limit generalizability to settings without such a champion and without dedicated time available with a pharmacist. Determining which groups of older veterans benefit most from individualized medication management and optimal methods to translate the program to other primary care settings are ongoing endeavors for the Atlanta GRECC IMPROVE team.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a VA Transformation-21 grant awarded through the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care. The authors thank Christine Jasien, MS; for data management, Aaron Bozzorg, MS; for interview transcription, Joette Lowe, PharmD; for general consultation; and the VISN 7 leadership for their support.

1. Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, et al. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):34-41.

2. Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, et al. Effects of geriatric evaluation and management on adverse drug reactions and suboptimal prescribing in the frail elderly. Am J Med. 2004;116(6):394-401.

3. Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, et al. Pharmacist‐led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized, controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing. 2001;30(3):205-211.

4. Chumney EC, Robinson LC. The effects of pharmacist interventions on patients with polypharmacy. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2006;4(3):103-109.

5. Lee JK, Slack MK, Martin J, Ehrman C, Chrisholm-Burns M. Geriatric patient care by U.S. pharmacists in healthcare teams: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1119-1127.

6. Veterans Health Administration Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce. Improving Patient-Centered Medication Management for Elderly Veterans: VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce Report and Recommendations. August 2010.

7. Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet. 2007;370(9582):173-184.

8. Mirk A, Kemp L, Echt KV, Perkins MM. Integrated management and polypharmacy review of vulnerable elders: Can we IMPROVE outcomes? [abstract]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(suppl 1):S92.

9. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-613.

10. Barry P, Gallagher P, Ryan C, O'Mahony D. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)--an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(6):632-638.

1. Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, et al. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):34-41.

2. Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, et al. Effects of geriatric evaluation and management on adverse drug reactions and suboptimal prescribing in the frail elderly. Am J Med. 2004;116(6):394-401.

3. Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, et al. Pharmacist‐led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized, controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing. 2001;30(3):205-211.

4. Chumney EC, Robinson LC. The effects of pharmacist interventions on patients with polypharmacy. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2006;4(3):103-109.

5. Lee JK, Slack MK, Martin J, Ehrman C, Chrisholm-Burns M. Geriatric patient care by U.S. pharmacists in healthcare teams: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1119-1127.

6. Veterans Health Administration Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce. Improving Patient-Centered Medication Management for Elderly Veterans: VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce Report and Recommendations. August 2010.

7. Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet. 2007;370(9582):173-184.

8. Mirk A, Kemp L, Echt KV, Perkins MM. Integrated management and polypharmacy review of vulnerable elders: Can we IMPROVE outcomes? [abstract]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(suppl 1):S92.

9. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-613.

10. Barry P, Gallagher P, Ryan C, O'Mahony D. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)--an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(6):632-638.