User login

Black Salve and Bloodroot Extract in Dermatologic Conditions

Black salve is composed of various ingredients, many of which are inert; however, some black salves contain escharotics, the 2 most common are zinc chloride and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) extract. In high doses, such as those contained in most black salve products, these corrosive agents can indiscriminately damage both healthy and diseased tissue.1 Nevertheless, many black salve products currently are advertised as safe and natural methods for curing skin cancer2-4 or treating a variety of other skin conditions (eg, moles, warts, skin tags, boils, abscesses, bee stings, other minor wounds)1,5 and even nondermatologic conditions such as a sore throat.6 Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies. Black salve is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions. We report the case of application of black salve to a biopsy site of a compound nevus with moderate atypia that resulted in the formation of a dermatitis plaque with subsequent scarring and basal layer pigmentation.

Case Report

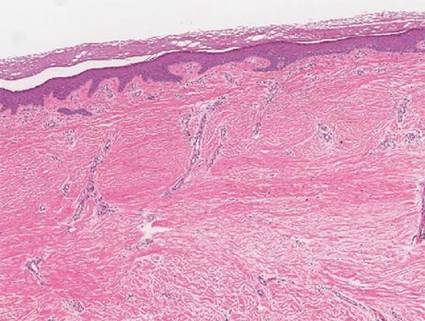

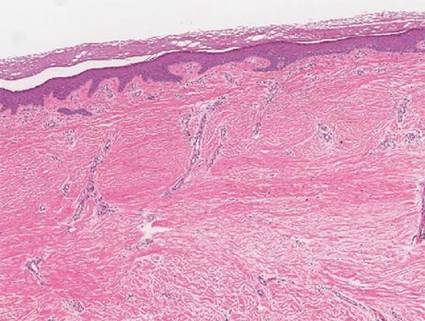

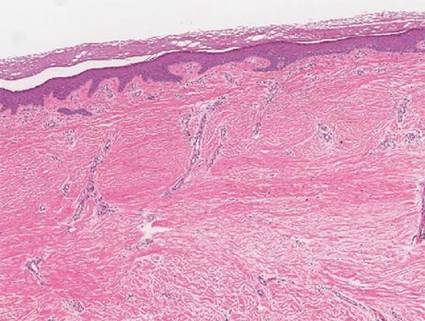

A 35-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma presented for follow-up of a compound nevus with moderate atypia on the right anterior thigh that had been biopsied 6 months prior. Complete excision of the lesion was recommended at the initial presentation but was not performed due to scheduling conflicts. The patient reported applying black salve to the biopsy site and also to the left thigh 3 months later. There was no reaction on the left thigh after one 24-hour application of black salve, but an area around the biopsy site on the right thigh became thickened and irritated with superficial erosion of the skin following 2 applications of black salve, each of 24 hours’ duration. Physical examination revealed a granulomatous plaque at the biopsy site that was approximately 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). One year later the lesion had completely healed (Figure 1B) and a biopsy revealed scarring with basal layer pigmentation (Figure 2).

|  |  | |||

| Figure 1. A 5-cm granulomatous reaction surrounding a biopsy site on the right anterior thigh 3 months after application of black salve (A). One year later, the lesion had completely healed (B). | Figure 2. A biopsy one year following application of black salve demonstrated scarring with basal layer pigmentation (H&E, original magnification ×4). | ||||

Comment

A Web search using the term black salve yields a large number of products labeled as skin cancer salves, many showing glowing reviews and some being sold by major US retailers. The ingredients in black salves often vary in the innocuous substances they contain, but most products include the escharotics zinc chloride and bloodroot extract, which is derived from the plant S canadensis.1,3 For example, the ingredients of one popular black salve product include zinc chloride, chaparral (active ingredient is nordihydroguaiaretic acid), graviola leaf extract, oleander leaf extract, bloodroot extract, and glycerine,7 while another product includes bloodroot extract, zinc chloride, chaparral, cayenne pepper, red clover, birch bark, dimethyl sulfoxide, and burdock root.4

Bloodroot extract’s antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects derive from its benzylisoquinoline alkaloids including sanguinarine, allocryptopine, berberine, coptisine, protopine, and stylopine.3,8 Bloodroot extract possesses some degree of tumoricidal potency, with one study finding that it selectively targets cancer cells.9 However, this differential response is seen only at low doses and not at the high concentrations contained in most black salve products.1 According to fluorometric assays, sanguinarine is not selective for tumor cells and therefore damages healthy tissue in addition to the unwanted lesions.6,10,11 The US Food and Drug Administration includes black salve products on its list of fake cancer cures that consumers should avoid.12 Reports of extensive damage from black salve use include skin ulceration2,10 and complete loss of a naris1 and nasal ala.5 Our case suggests the possible association between black salve use and an irritant reaction and erosion of the skin.

Furthermore, reliance on black salve alone in the treatment of skin cancer poses the threat of recurrence or metastasis of cancer because there is no way to know if the salve completely removed the cancer without a biopsy. Self-treatment can delay more effective therapy and may require further treatments.

Black salve should be subject to standarddrug regulations and its use discouraged by dermatologists due to the associated harmful effects and the availability of safer treatments. To better treat and inform their patients, dermatologists should be aware that patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves.

1. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289.

2. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e154-e155.

3. Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80.

4. McDaniel S, Goldman GD. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

5. Payne CE. ‘Black Salve’ and melanomas [published online ahead of print August 11, 2010]. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:422.

6. Cienki JJ, Zaret L. An Internet misadventure: bloodroot salve toxicity. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1125-1127.

7. Cansema and escharotics. Alpha Omega Labs Web site. http://www.altcancer.com/faqcan.htm. Accessed May 6, 2015.

8. Vlachojannis C, Magora F, Chrubasik S. Rise and fall of oral health products with Canadian bloodroot extract. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1423-1426.

9. Ahmad N, Gupta S, Husain MM, et al. Differential antiproliferative and apoptotic response of sanguinarine for cancer cells versus normal cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1524-1528.

10. Saltzberg F, Barron G, Fenske N. Deforming self-treatment with herbal “black salve.” Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1152-1154.

11. Debiton E, Madelmont JC, Legault J, et al. Sanguinarine-induced apoptosis is associated with an early and severe cellular glutathione depletion. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:474-482.

12. 187 fake cancer “cures” consumers should avoid. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceCompliance RegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/ucm171057.htm. Updated July 9, 2009. Accessed May 6, 2015.

Black salve is composed of various ingredients, many of which are inert; however, some black salves contain escharotics, the 2 most common are zinc chloride and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) extract. In high doses, such as those contained in most black salve products, these corrosive agents can indiscriminately damage both healthy and diseased tissue.1 Nevertheless, many black salve products currently are advertised as safe and natural methods for curing skin cancer2-4 or treating a variety of other skin conditions (eg, moles, warts, skin tags, boils, abscesses, bee stings, other minor wounds)1,5 and even nondermatologic conditions such as a sore throat.6 Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies. Black salve is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions. We report the case of application of black salve to a biopsy site of a compound nevus with moderate atypia that resulted in the formation of a dermatitis plaque with subsequent scarring and basal layer pigmentation.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma presented for follow-up of a compound nevus with moderate atypia on the right anterior thigh that had been biopsied 6 months prior. Complete excision of the lesion was recommended at the initial presentation but was not performed due to scheduling conflicts. The patient reported applying black salve to the biopsy site and also to the left thigh 3 months later. There was no reaction on the left thigh after one 24-hour application of black salve, but an area around the biopsy site on the right thigh became thickened and irritated with superficial erosion of the skin following 2 applications of black salve, each of 24 hours’ duration. Physical examination revealed a granulomatous plaque at the biopsy site that was approximately 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). One year later the lesion had completely healed (Figure 1B) and a biopsy revealed scarring with basal layer pigmentation (Figure 2).

|  |  | |||

| Figure 1. A 5-cm granulomatous reaction surrounding a biopsy site on the right anterior thigh 3 months after application of black salve (A). One year later, the lesion had completely healed (B). | Figure 2. A biopsy one year following application of black salve demonstrated scarring with basal layer pigmentation (H&E, original magnification ×4). | ||||

Comment

A Web search using the term black salve yields a large number of products labeled as skin cancer salves, many showing glowing reviews and some being sold by major US retailers. The ingredients in black salves often vary in the innocuous substances they contain, but most products include the escharotics zinc chloride and bloodroot extract, which is derived from the plant S canadensis.1,3 For example, the ingredients of one popular black salve product include zinc chloride, chaparral (active ingredient is nordihydroguaiaretic acid), graviola leaf extract, oleander leaf extract, bloodroot extract, and glycerine,7 while another product includes bloodroot extract, zinc chloride, chaparral, cayenne pepper, red clover, birch bark, dimethyl sulfoxide, and burdock root.4

Bloodroot extract’s antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects derive from its benzylisoquinoline alkaloids including sanguinarine, allocryptopine, berberine, coptisine, protopine, and stylopine.3,8 Bloodroot extract possesses some degree of tumoricidal potency, with one study finding that it selectively targets cancer cells.9 However, this differential response is seen only at low doses and not at the high concentrations contained in most black salve products.1 According to fluorometric assays, sanguinarine is not selective for tumor cells and therefore damages healthy tissue in addition to the unwanted lesions.6,10,11 The US Food and Drug Administration includes black salve products on its list of fake cancer cures that consumers should avoid.12 Reports of extensive damage from black salve use include skin ulceration2,10 and complete loss of a naris1 and nasal ala.5 Our case suggests the possible association between black salve use and an irritant reaction and erosion of the skin.

Furthermore, reliance on black salve alone in the treatment of skin cancer poses the threat of recurrence or metastasis of cancer because there is no way to know if the salve completely removed the cancer without a biopsy. Self-treatment can delay more effective therapy and may require further treatments.

Black salve should be subject to standarddrug regulations and its use discouraged by dermatologists due to the associated harmful effects and the availability of safer treatments. To better treat and inform their patients, dermatologists should be aware that patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves.

Black salve is composed of various ingredients, many of which are inert; however, some black salves contain escharotics, the 2 most common are zinc chloride and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) extract. In high doses, such as those contained in most black salve products, these corrosive agents can indiscriminately damage both healthy and diseased tissue.1 Nevertheless, many black salve products currently are advertised as safe and natural methods for curing skin cancer2-4 or treating a variety of other skin conditions (eg, moles, warts, skin tags, boils, abscesses, bee stings, other minor wounds)1,5 and even nondermatologic conditions such as a sore throat.6 Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies. Black salve is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions. We report the case of application of black salve to a biopsy site of a compound nevus with moderate atypia that resulted in the formation of a dermatitis plaque with subsequent scarring and basal layer pigmentation.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma presented for follow-up of a compound nevus with moderate atypia on the right anterior thigh that had been biopsied 6 months prior. Complete excision of the lesion was recommended at the initial presentation but was not performed due to scheduling conflicts. The patient reported applying black salve to the biopsy site and also to the left thigh 3 months later. There was no reaction on the left thigh after one 24-hour application of black salve, but an area around the biopsy site on the right thigh became thickened and irritated with superficial erosion of the skin following 2 applications of black salve, each of 24 hours’ duration. Physical examination revealed a granulomatous plaque at the biopsy site that was approximately 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). One year later the lesion had completely healed (Figure 1B) and a biopsy revealed scarring with basal layer pigmentation (Figure 2).

|  |  | |||

| Figure 1. A 5-cm granulomatous reaction surrounding a biopsy site on the right anterior thigh 3 months after application of black salve (A). One year later, the lesion had completely healed (B). | Figure 2. A biopsy one year following application of black salve demonstrated scarring with basal layer pigmentation (H&E, original magnification ×4). | ||||

Comment

A Web search using the term black salve yields a large number of products labeled as skin cancer salves, many showing glowing reviews and some being sold by major US retailers. The ingredients in black salves often vary in the innocuous substances they contain, but most products include the escharotics zinc chloride and bloodroot extract, which is derived from the plant S canadensis.1,3 For example, the ingredients of one popular black salve product include zinc chloride, chaparral (active ingredient is nordihydroguaiaretic acid), graviola leaf extract, oleander leaf extract, bloodroot extract, and glycerine,7 while another product includes bloodroot extract, zinc chloride, chaparral, cayenne pepper, red clover, birch bark, dimethyl sulfoxide, and burdock root.4

Bloodroot extract’s antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects derive from its benzylisoquinoline alkaloids including sanguinarine, allocryptopine, berberine, coptisine, protopine, and stylopine.3,8 Bloodroot extract possesses some degree of tumoricidal potency, with one study finding that it selectively targets cancer cells.9 However, this differential response is seen only at low doses and not at the high concentrations contained in most black salve products.1 According to fluorometric assays, sanguinarine is not selective for tumor cells and therefore damages healthy tissue in addition to the unwanted lesions.6,10,11 The US Food and Drug Administration includes black salve products on its list of fake cancer cures that consumers should avoid.12 Reports of extensive damage from black salve use include skin ulceration2,10 and complete loss of a naris1 and nasal ala.5 Our case suggests the possible association between black salve use and an irritant reaction and erosion of the skin.

Furthermore, reliance on black salve alone in the treatment of skin cancer poses the threat of recurrence or metastasis of cancer because there is no way to know if the salve completely removed the cancer without a biopsy. Self-treatment can delay more effective therapy and may require further treatments.

Black salve should be subject to standarddrug regulations and its use discouraged by dermatologists due to the associated harmful effects and the availability of safer treatments. To better treat and inform their patients, dermatologists should be aware that patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves.

1. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289.

2. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e154-e155.

3. Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80.

4. McDaniel S, Goldman GD. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

5. Payne CE. ‘Black Salve’ and melanomas [published online ahead of print August 11, 2010]. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:422.

6. Cienki JJ, Zaret L. An Internet misadventure: bloodroot salve toxicity. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1125-1127.

7. Cansema and escharotics. Alpha Omega Labs Web site. http://www.altcancer.com/faqcan.htm. Accessed May 6, 2015.

8. Vlachojannis C, Magora F, Chrubasik S. Rise and fall of oral health products with Canadian bloodroot extract. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1423-1426.

9. Ahmad N, Gupta S, Husain MM, et al. Differential antiproliferative and apoptotic response of sanguinarine for cancer cells versus normal cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1524-1528.

10. Saltzberg F, Barron G, Fenske N. Deforming self-treatment with herbal “black salve.” Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1152-1154.

11. Debiton E, Madelmont JC, Legault J, et al. Sanguinarine-induced apoptosis is associated with an early and severe cellular glutathione depletion. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:474-482.

12. 187 fake cancer “cures” consumers should avoid. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceCompliance RegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/ucm171057.htm. Updated July 9, 2009. Accessed May 6, 2015.

1. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289.

2. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e154-e155.

3. Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80.

4. McDaniel S, Goldman GD. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

5. Payne CE. ‘Black Salve’ and melanomas [published online ahead of print August 11, 2010]. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:422.

6. Cienki JJ, Zaret L. An Internet misadventure: bloodroot salve toxicity. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1125-1127.

7. Cansema and escharotics. Alpha Omega Labs Web site. http://www.altcancer.com/faqcan.htm. Accessed May 6, 2015.

8. Vlachojannis C, Magora F, Chrubasik S. Rise and fall of oral health products with Canadian bloodroot extract. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1423-1426.

9. Ahmad N, Gupta S, Husain MM, et al. Differential antiproliferative and apoptotic response of sanguinarine for cancer cells versus normal cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1524-1528.

10. Saltzberg F, Barron G, Fenske N. Deforming self-treatment with herbal “black salve.” Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1152-1154.

11. Debiton E, Madelmont JC, Legault J, et al. Sanguinarine-induced apoptosis is associated with an early and severe cellular glutathione depletion. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:474-482.

12. 187 fake cancer “cures” consumers should avoid. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceCompliance RegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/ucm171057.htm. Updated July 9, 2009. Accessed May 6, 2015.

Practice Points

- Clinicians should be aware that black salve containing bloodroot extract is a popular alternative treatment used to cure a variety of skin ailments.

- Black salve containing bloodroot extract is not selective for tumor cells. Various case reports have shown that black salve can result in extensive tissue damage and recurrence or metastasis of skin cancer.

- Damage to healthy tissue can occur with as few as 2 applications of black salve.