User login

Black Salve and Bloodroot Extract in Dermatologic Conditions

Black salve is composed of various ingredients, many of which are inert; however, some black salves contain escharotics, the 2 most common are zinc chloride and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) extract. In high doses, such as those contained in most black salve products, these corrosive agents can indiscriminately damage both healthy and diseased tissue.1 Nevertheless, many black salve products currently are advertised as safe and natural methods for curing skin cancer2-4 or treating a variety of other skin conditions (eg, moles, warts, skin tags, boils, abscesses, bee stings, other minor wounds)1,5 and even nondermatologic conditions such as a sore throat.6 Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies. Black salve is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions. We report the case of application of black salve to a biopsy site of a compound nevus with moderate atypia that resulted in the formation of a dermatitis plaque with subsequent scarring and basal layer pigmentation.

Case Report

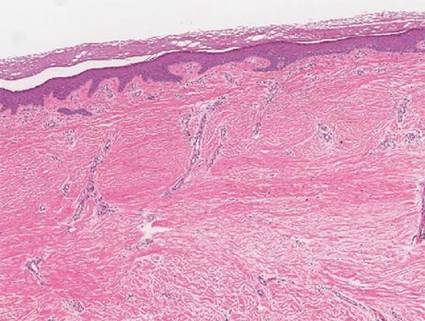

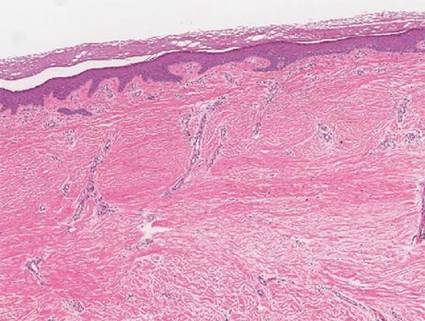

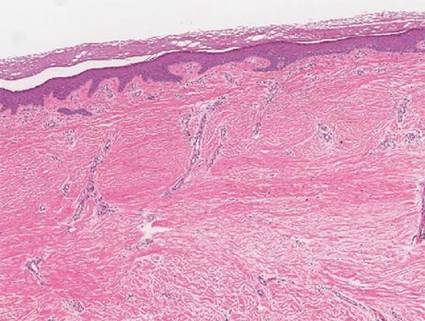

A 35-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma presented for follow-up of a compound nevus with moderate atypia on the right anterior thigh that had been biopsied 6 months prior. Complete excision of the lesion was recommended at the initial presentation but was not performed due to scheduling conflicts. The patient reported applying black salve to the biopsy site and also to the left thigh 3 months later. There was no reaction on the left thigh after one 24-hour application of black salve, but an area around the biopsy site on the right thigh became thickened and irritated with superficial erosion of the skin following 2 applications of black salve, each of 24 hours’ duration. Physical examination revealed a granulomatous plaque at the biopsy site that was approximately 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). One year later the lesion had completely healed (Figure 1B) and a biopsy revealed scarring with basal layer pigmentation (Figure 2).

|  |  | |||

| Figure 1. A 5-cm granulomatous reaction surrounding a biopsy site on the right anterior thigh 3 months after application of black salve (A). One year later, the lesion had completely healed (B). | Figure 2. A biopsy one year following application of black salve demonstrated scarring with basal layer pigmentation (H&E, original magnification ×4). | ||||

Comment

A Web search using the term black salve yields a large number of products labeled as skin cancer salves, many showing glowing reviews and some being sold by major US retailers. The ingredients in black salves often vary in the innocuous substances they contain, but most products include the escharotics zinc chloride and bloodroot extract, which is derived from the plant S canadensis.1,3 For example, the ingredients of one popular black salve product include zinc chloride, chaparral (active ingredient is nordihydroguaiaretic acid), graviola leaf extract, oleander leaf extract, bloodroot extract, and glycerine,7 while another product includes bloodroot extract, zinc chloride, chaparral, cayenne pepper, red clover, birch bark, dimethyl sulfoxide, and burdock root.4

Bloodroot extract’s antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects derive from its benzylisoquinoline alkaloids including sanguinarine, allocryptopine, berberine, coptisine, protopine, and stylopine.3,8 Bloodroot extract possesses some degree of tumoricidal potency, with one study finding that it selectively targets cancer cells.9 However, this differential response is seen only at low doses and not at the high concentrations contained in most black salve products.1 According to fluorometric assays, sanguinarine is not selective for tumor cells and therefore damages healthy tissue in addition to the unwanted lesions.6,10,11 The US Food and Drug Administration includes black salve products on its list of fake cancer cures that consumers should avoid.12 Reports of extensive damage from black salve use include skin ulceration2,10 and complete loss of a naris1 and nasal ala.5 Our case suggests the possible association between black salve use and an irritant reaction and erosion of the skin.

Furthermore, reliance on black salve alone in the treatment of skin cancer poses the threat of recurrence or metastasis of cancer because there is no way to know if the salve completely removed the cancer without a biopsy. Self-treatment can delay more effective therapy and may require further treatments.

Black salve should be subject to standarddrug regulations and its use discouraged by dermatologists due to the associated harmful effects and the availability of safer treatments. To better treat and inform their patients, dermatologists should be aware that patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves.

1. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289.

2. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e154-e155.

3. Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80.

4. McDaniel S, Goldman GD. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

5. Payne CE. ‘Black Salve’ and melanomas [published online ahead of print August 11, 2010]. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:422.

6. Cienki JJ, Zaret L. An Internet misadventure: bloodroot salve toxicity. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1125-1127.

7. Cansema and escharotics. Alpha Omega Labs Web site. http://www.altcancer.com/faqcan.htm. Accessed May 6, 2015.

8. Vlachojannis C, Magora F, Chrubasik S. Rise and fall of oral health products with Canadian bloodroot extract. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1423-1426.

9. Ahmad N, Gupta S, Husain MM, et al. Differential antiproliferative and apoptotic response of sanguinarine for cancer cells versus normal cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1524-1528.

10. Saltzberg F, Barron G, Fenske N. Deforming self-treatment with herbal “black salve.” Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1152-1154.

11. Debiton E, Madelmont JC, Legault J, et al. Sanguinarine-induced apoptosis is associated with an early and severe cellular glutathione depletion. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:474-482.

12. 187 fake cancer “cures” consumers should avoid. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceCompliance RegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/ucm171057.htm. Updated July 9, 2009. Accessed May 6, 2015.

Black salve is composed of various ingredients, many of which are inert; however, some black salves contain escharotics, the 2 most common are zinc chloride and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) extract. In high doses, such as those contained in most black salve products, these corrosive agents can indiscriminately damage both healthy and diseased tissue.1 Nevertheless, many black salve products currently are advertised as safe and natural methods for curing skin cancer2-4 or treating a variety of other skin conditions (eg, moles, warts, skin tags, boils, abscesses, bee stings, other minor wounds)1,5 and even nondermatologic conditions such as a sore throat.6 Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies. Black salve is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions. We report the case of application of black salve to a biopsy site of a compound nevus with moderate atypia that resulted in the formation of a dermatitis plaque with subsequent scarring and basal layer pigmentation.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma presented for follow-up of a compound nevus with moderate atypia on the right anterior thigh that had been biopsied 6 months prior. Complete excision of the lesion was recommended at the initial presentation but was not performed due to scheduling conflicts. The patient reported applying black salve to the biopsy site and also to the left thigh 3 months later. There was no reaction on the left thigh after one 24-hour application of black salve, but an area around the biopsy site on the right thigh became thickened and irritated with superficial erosion of the skin following 2 applications of black salve, each of 24 hours’ duration. Physical examination revealed a granulomatous plaque at the biopsy site that was approximately 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). One year later the lesion had completely healed (Figure 1B) and a biopsy revealed scarring with basal layer pigmentation (Figure 2).

|  |  | |||

| Figure 1. A 5-cm granulomatous reaction surrounding a biopsy site on the right anterior thigh 3 months after application of black salve (A). One year later, the lesion had completely healed (B). | Figure 2. A biopsy one year following application of black salve demonstrated scarring with basal layer pigmentation (H&E, original magnification ×4). | ||||

Comment

A Web search using the term black salve yields a large number of products labeled as skin cancer salves, many showing glowing reviews and some being sold by major US retailers. The ingredients in black salves often vary in the innocuous substances they contain, but most products include the escharotics zinc chloride and bloodroot extract, which is derived from the plant S canadensis.1,3 For example, the ingredients of one popular black salve product include zinc chloride, chaparral (active ingredient is nordihydroguaiaretic acid), graviola leaf extract, oleander leaf extract, bloodroot extract, and glycerine,7 while another product includes bloodroot extract, zinc chloride, chaparral, cayenne pepper, red clover, birch bark, dimethyl sulfoxide, and burdock root.4

Bloodroot extract’s antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects derive from its benzylisoquinoline alkaloids including sanguinarine, allocryptopine, berberine, coptisine, protopine, and stylopine.3,8 Bloodroot extract possesses some degree of tumoricidal potency, with one study finding that it selectively targets cancer cells.9 However, this differential response is seen only at low doses and not at the high concentrations contained in most black salve products.1 According to fluorometric assays, sanguinarine is not selective for tumor cells and therefore damages healthy tissue in addition to the unwanted lesions.6,10,11 The US Food and Drug Administration includes black salve products on its list of fake cancer cures that consumers should avoid.12 Reports of extensive damage from black salve use include skin ulceration2,10 and complete loss of a naris1 and nasal ala.5 Our case suggests the possible association between black salve use and an irritant reaction and erosion of the skin.

Furthermore, reliance on black salve alone in the treatment of skin cancer poses the threat of recurrence or metastasis of cancer because there is no way to know if the salve completely removed the cancer without a biopsy. Self-treatment can delay more effective therapy and may require further treatments.

Black salve should be subject to standarddrug regulations and its use discouraged by dermatologists due to the associated harmful effects and the availability of safer treatments. To better treat and inform their patients, dermatologists should be aware that patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves.

Black salve is composed of various ingredients, many of which are inert; however, some black salves contain escharotics, the 2 most common are zinc chloride and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) extract. In high doses, such as those contained in most black salve products, these corrosive agents can indiscriminately damage both healthy and diseased tissue.1 Nevertheless, many black salve products currently are advertised as safe and natural methods for curing skin cancer2-4 or treating a variety of other skin conditions (eg, moles, warts, skin tags, boils, abscesses, bee stings, other minor wounds)1,5 and even nondermatologic conditions such as a sore throat.6 Despite the information and testimonials that are widely available on the Internet, black salve use has not been validated by rigorous studies. Black salve is not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, resulting in poor quality control and inconsistent user instructions. We report the case of application of black salve to a biopsy site of a compound nevus with moderate atypia that resulted in the formation of a dermatitis plaque with subsequent scarring and basal layer pigmentation.

Case Report

A 35-year-old woman with a family history of melanoma presented for follow-up of a compound nevus with moderate atypia on the right anterior thigh that had been biopsied 6 months prior. Complete excision of the lesion was recommended at the initial presentation but was not performed due to scheduling conflicts. The patient reported applying black salve to the biopsy site and also to the left thigh 3 months later. There was no reaction on the left thigh after one 24-hour application of black salve, but an area around the biopsy site on the right thigh became thickened and irritated with superficial erosion of the skin following 2 applications of black salve, each of 24 hours’ duration. Physical examination revealed a granulomatous plaque at the biopsy site that was approximately 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). One year later the lesion had completely healed (Figure 1B) and a biopsy revealed scarring with basal layer pigmentation (Figure 2).

|  |  | |||

| Figure 1. A 5-cm granulomatous reaction surrounding a biopsy site on the right anterior thigh 3 months after application of black salve (A). One year later, the lesion had completely healed (B). | Figure 2. A biopsy one year following application of black salve demonstrated scarring with basal layer pigmentation (H&E, original magnification ×4). | ||||

Comment

A Web search using the term black salve yields a large number of products labeled as skin cancer salves, many showing glowing reviews and some being sold by major US retailers. The ingredients in black salves often vary in the innocuous substances they contain, but most products include the escharotics zinc chloride and bloodroot extract, which is derived from the plant S canadensis.1,3 For example, the ingredients of one popular black salve product include zinc chloride, chaparral (active ingredient is nordihydroguaiaretic acid), graviola leaf extract, oleander leaf extract, bloodroot extract, and glycerine,7 while another product includes bloodroot extract, zinc chloride, chaparral, cayenne pepper, red clover, birch bark, dimethyl sulfoxide, and burdock root.4

Bloodroot extract’s antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects derive from its benzylisoquinoline alkaloids including sanguinarine, allocryptopine, berberine, coptisine, protopine, and stylopine.3,8 Bloodroot extract possesses some degree of tumoricidal potency, with one study finding that it selectively targets cancer cells.9 However, this differential response is seen only at low doses and not at the high concentrations contained in most black salve products.1 According to fluorometric assays, sanguinarine is not selective for tumor cells and therefore damages healthy tissue in addition to the unwanted lesions.6,10,11 The US Food and Drug Administration includes black salve products on its list of fake cancer cures that consumers should avoid.12 Reports of extensive damage from black salve use include skin ulceration2,10 and complete loss of a naris1 and nasal ala.5 Our case suggests the possible association between black salve use and an irritant reaction and erosion of the skin.

Furthermore, reliance on black salve alone in the treatment of skin cancer poses the threat of recurrence or metastasis of cancer because there is no way to know if the salve completely removed the cancer without a biopsy. Self-treatment can delay more effective therapy and may require further treatments.

Black salve should be subject to standarddrug regulations and its use discouraged by dermatologists due to the associated harmful effects and the availability of safer treatments. To better treat and inform their patients, dermatologists should be aware that patients may be attracted to alternative treatments such as black salves.

1. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289.

2. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e154-e155.

3. Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80.

4. McDaniel S, Goldman GD. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

5. Payne CE. ‘Black Salve’ and melanomas [published online ahead of print August 11, 2010]. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:422.

6. Cienki JJ, Zaret L. An Internet misadventure: bloodroot salve toxicity. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1125-1127.

7. Cansema and escharotics. Alpha Omega Labs Web site. http://www.altcancer.com/faqcan.htm. Accessed May 6, 2015.

8. Vlachojannis C, Magora F, Chrubasik S. Rise and fall of oral health products with Canadian bloodroot extract. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1423-1426.

9. Ahmad N, Gupta S, Husain MM, et al. Differential antiproliferative and apoptotic response of sanguinarine for cancer cells versus normal cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1524-1528.

10. Saltzberg F, Barron G, Fenske N. Deforming self-treatment with herbal “black salve.” Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1152-1154.

11. Debiton E, Madelmont JC, Legault J, et al. Sanguinarine-induced apoptosis is associated with an early and severe cellular glutathione depletion. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:474-482.

12. 187 fake cancer “cures” consumers should avoid. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceCompliance RegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/ucm171057.htm. Updated July 9, 2009. Accessed May 6, 2015.

1. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:284-289.

2. Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e154-e155.

3. Sivyer GW, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:77-80.

4. McDaniel S, Goldman GD. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593-1596.

5. Payne CE. ‘Black Salve’ and melanomas [published online ahead of print August 11, 2010]. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:422.

6. Cienki JJ, Zaret L. An Internet misadventure: bloodroot salve toxicity. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1125-1127.

7. Cansema and escharotics. Alpha Omega Labs Web site. http://www.altcancer.com/faqcan.htm. Accessed May 6, 2015.

8. Vlachojannis C, Magora F, Chrubasik S. Rise and fall of oral health products with Canadian bloodroot extract. Phytother Res. 2012;26:1423-1426.

9. Ahmad N, Gupta S, Husain MM, et al. Differential antiproliferative and apoptotic response of sanguinarine for cancer cells versus normal cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1524-1528.

10. Saltzberg F, Barron G, Fenske N. Deforming self-treatment with herbal “black salve.” Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1152-1154.

11. Debiton E, Madelmont JC, Legault J, et al. Sanguinarine-induced apoptosis is associated with an early and severe cellular glutathione depletion. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:474-482.

12. 187 fake cancer “cures” consumers should avoid. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceCompliance RegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/ucm171057.htm. Updated July 9, 2009. Accessed May 6, 2015.

Practice Points

- Clinicians should be aware that black salve containing bloodroot extract is a popular alternative treatment used to cure a variety of skin ailments.

- Black salve containing bloodroot extract is not selective for tumor cells. Various case reports have shown that black salve can result in extensive tissue damage and recurrence or metastasis of skin cancer.

- Damage to healthy tissue can occur with as few as 2 applications of black salve.

A Case of Pruritis Rash

History of Present Illness

A55-year-old male presented with a one and one-half week history of a sore throat, shortness of breath on exertion, ankle edema, and arthralgias that began in the ankles and subsequently spread to involve the elbows and wrists.

He had also developed a pruritic eruption involving the lower extremities, which consisted of erythematous palpable purpuric lesions and patches with superficial and central necrosis and ulceration, as well as a large 4-cm bulla of the right lateral ankle. (See Figures 1 and 2, below.) Other skin findings included petechiae of the palms and multiple ulcerations of the hard palate. Laboratory evaluation demonstrated c-ANCA antibody positivity (1:512), a proteinase 3 antibody level of greater than 100 U/ml, and a creatinine of 1.0mg/dl. TH

What is the most appropriate treatment for this condition?

- Prednisone;

- Azathioprine;

- Cyclophosphamide;

- Prednisone combined with cyclophosphamide; or

- Vancomycin combined with rifampin

Discussion

The answer is D: Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory response of unknown etiology that usually presents with the classic triad of systemic vasculitis, necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the upper and lower respiratory tracts, and glomerulonephritis. The generalized or classic form of WG can progress rapidly to cause irreversible organ dysfunction and death. Although the pathogenesis remains unknown, it is felt that WG may result from an exaggerated cell-mediated response to an unknown antigen.1

The average age of onset for WG is 45.2 years, with 63.5% of patients male and 91% Caucasian.2 A WG diagnosis can be very difficult, and elements of the classic triad may not all be present initially. Pulmonary infiltrates or nodules are seen via chest X-ray or CT scan in just less than half of patients as an early manifestation of WG.

Occasionally WG presents with skin lesions (13%) or oral ulcers (6%), however, 40% of patients eventually develop skin involvement consisting of painful subcutaneous nodules, papules, vesicles or bullae, petechiae, palpable purpura, and pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions.3 Histologic evaluation of these skin lesions reveals non-specific perivascular lymphocytic inflammation, leukocytoclastic vasculitis-like changes, palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis; however, it is rare to see granulomatous vasculitis or palisading necrotizing granulomas in skin specimens.4,5

WG can also affect the eyes, heart, respiratory system, nervous system, kidneys, and joints.6 The upper respiratory tract is involved in the majority of patients, and symptoms reflecting otitis, epistaxis, rhinorrhea, or sinusitis are common and may be the first manifestation of disease. When mucosal necrotizing granulomas occur, they can result in the typical saddle nose deformity seen in patients with WG. Lower respiratory tract involvement is also common and can present with cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis.1

Patients with WG usually have a positive c-ANCA, however this is not specific for WG and may also indicate Churg-Strauss Syndrome and microscopic polyarteritis. The median survival of patients with untreated WG is five months, and corticosteroids used alone do not change this median survival. When corticosteroids are combined with cytotoxic agents, such as cyclophosphamide, the prognosis significantly improves in greater than 90% of patients, with a 75% remission rate, and an 87% survival of patients followed from six months to 24 years.3 TH

References

- Hannon CW, Swerlick RA. Vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. New York: Elsevier Limited; 2003: 393-395.

- Cotch MF, Hoffman GS, Yerg DE, et al. The epidemiology of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Estimates of the five-year period prevalence, annual mortality, and geographic disease distribution from population-based data sources. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 Jan;39(1):87-92.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. [see comments]. Ann Int Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Hu CH, O’Loughlin S, Winkelmann RK. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener granulomatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1997;113(2):175-182.

- Lie JT. Wegener’s granulomatosis: histological documentation of common and uncommon manifestations in 216 patients. Vasa. 1997;26:261-270.

- Yi ES, Colby TV. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2001 Feb;18(1):34-46.

History of Present Illness

A55-year-old male presented with a one and one-half week history of a sore throat, shortness of breath on exertion, ankle edema, and arthralgias that began in the ankles and subsequently spread to involve the elbows and wrists.

He had also developed a pruritic eruption involving the lower extremities, which consisted of erythematous palpable purpuric lesions and patches with superficial and central necrosis and ulceration, as well as a large 4-cm bulla of the right lateral ankle. (See Figures 1 and 2, below.) Other skin findings included petechiae of the palms and multiple ulcerations of the hard palate. Laboratory evaluation demonstrated c-ANCA antibody positivity (1:512), a proteinase 3 antibody level of greater than 100 U/ml, and a creatinine of 1.0mg/dl. TH

What is the most appropriate treatment for this condition?

- Prednisone;

- Azathioprine;

- Cyclophosphamide;

- Prednisone combined with cyclophosphamide; or

- Vancomycin combined with rifampin

Discussion

The answer is D: Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory response of unknown etiology that usually presents with the classic triad of systemic vasculitis, necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the upper and lower respiratory tracts, and glomerulonephritis. The generalized or classic form of WG can progress rapidly to cause irreversible organ dysfunction and death. Although the pathogenesis remains unknown, it is felt that WG may result from an exaggerated cell-mediated response to an unknown antigen.1

The average age of onset for WG is 45.2 years, with 63.5% of patients male and 91% Caucasian.2 A WG diagnosis can be very difficult, and elements of the classic triad may not all be present initially. Pulmonary infiltrates or nodules are seen via chest X-ray or CT scan in just less than half of patients as an early manifestation of WG.

Occasionally WG presents with skin lesions (13%) or oral ulcers (6%), however, 40% of patients eventually develop skin involvement consisting of painful subcutaneous nodules, papules, vesicles or bullae, petechiae, palpable purpura, and pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions.3 Histologic evaluation of these skin lesions reveals non-specific perivascular lymphocytic inflammation, leukocytoclastic vasculitis-like changes, palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis; however, it is rare to see granulomatous vasculitis or palisading necrotizing granulomas in skin specimens.4,5

WG can also affect the eyes, heart, respiratory system, nervous system, kidneys, and joints.6 The upper respiratory tract is involved in the majority of patients, and symptoms reflecting otitis, epistaxis, rhinorrhea, or sinusitis are common and may be the first manifestation of disease. When mucosal necrotizing granulomas occur, they can result in the typical saddle nose deformity seen in patients with WG. Lower respiratory tract involvement is also common and can present with cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis.1

Patients with WG usually have a positive c-ANCA, however this is not specific for WG and may also indicate Churg-Strauss Syndrome and microscopic polyarteritis. The median survival of patients with untreated WG is five months, and corticosteroids used alone do not change this median survival. When corticosteroids are combined with cytotoxic agents, such as cyclophosphamide, the prognosis significantly improves in greater than 90% of patients, with a 75% remission rate, and an 87% survival of patients followed from six months to 24 years.3 TH

References

- Hannon CW, Swerlick RA. Vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. New York: Elsevier Limited; 2003: 393-395.

- Cotch MF, Hoffman GS, Yerg DE, et al. The epidemiology of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Estimates of the five-year period prevalence, annual mortality, and geographic disease distribution from population-based data sources. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 Jan;39(1):87-92.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. [see comments]. Ann Int Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Hu CH, O’Loughlin S, Winkelmann RK. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener granulomatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1997;113(2):175-182.

- Lie JT. Wegener’s granulomatosis: histological documentation of common and uncommon manifestations in 216 patients. Vasa. 1997;26:261-270.

- Yi ES, Colby TV. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2001 Feb;18(1):34-46.

History of Present Illness

A55-year-old male presented with a one and one-half week history of a sore throat, shortness of breath on exertion, ankle edema, and arthralgias that began in the ankles and subsequently spread to involve the elbows and wrists.

He had also developed a pruritic eruption involving the lower extremities, which consisted of erythematous palpable purpuric lesions and patches with superficial and central necrosis and ulceration, as well as a large 4-cm bulla of the right lateral ankle. (See Figures 1 and 2, below.) Other skin findings included petechiae of the palms and multiple ulcerations of the hard palate. Laboratory evaluation demonstrated c-ANCA antibody positivity (1:512), a proteinase 3 antibody level of greater than 100 U/ml, and a creatinine of 1.0mg/dl. TH

What is the most appropriate treatment for this condition?

- Prednisone;

- Azathioprine;

- Cyclophosphamide;

- Prednisone combined with cyclophosphamide; or

- Vancomycin combined with rifampin

Discussion

The answer is D: Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory response of unknown etiology that usually presents with the classic triad of systemic vasculitis, necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the upper and lower respiratory tracts, and glomerulonephritis. The generalized or classic form of WG can progress rapidly to cause irreversible organ dysfunction and death. Although the pathogenesis remains unknown, it is felt that WG may result from an exaggerated cell-mediated response to an unknown antigen.1

The average age of onset for WG is 45.2 years, with 63.5% of patients male and 91% Caucasian.2 A WG diagnosis can be very difficult, and elements of the classic triad may not all be present initially. Pulmonary infiltrates or nodules are seen via chest X-ray or CT scan in just less than half of patients as an early manifestation of WG.

Occasionally WG presents with skin lesions (13%) or oral ulcers (6%), however, 40% of patients eventually develop skin involvement consisting of painful subcutaneous nodules, papules, vesicles or bullae, petechiae, palpable purpura, and pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions.3 Histologic evaluation of these skin lesions reveals non-specific perivascular lymphocytic inflammation, leukocytoclastic vasculitis-like changes, palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis; however, it is rare to see granulomatous vasculitis or palisading necrotizing granulomas in skin specimens.4,5

WG can also affect the eyes, heart, respiratory system, nervous system, kidneys, and joints.6 The upper respiratory tract is involved in the majority of patients, and symptoms reflecting otitis, epistaxis, rhinorrhea, or sinusitis are common and may be the first manifestation of disease. When mucosal necrotizing granulomas occur, they can result in the typical saddle nose deformity seen in patients with WG. Lower respiratory tract involvement is also common and can present with cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis.1

Patients with WG usually have a positive c-ANCA, however this is not specific for WG and may also indicate Churg-Strauss Syndrome and microscopic polyarteritis. The median survival of patients with untreated WG is five months, and corticosteroids used alone do not change this median survival. When corticosteroids are combined with cytotoxic agents, such as cyclophosphamide, the prognosis significantly improves in greater than 90% of patients, with a 75% remission rate, and an 87% survival of patients followed from six months to 24 years.3 TH

References

- Hannon CW, Swerlick RA. Vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. New York: Elsevier Limited; 2003: 393-395.

- Cotch MF, Hoffman GS, Yerg DE, et al. The epidemiology of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Estimates of the five-year period prevalence, annual mortality, and geographic disease distribution from population-based data sources. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 Jan;39(1):87-92.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. [see comments]. Ann Int Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Hu CH, O’Loughlin S, Winkelmann RK. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener granulomatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1997;113(2):175-182.

- Lie JT. Wegener’s granulomatosis: histological documentation of common and uncommon manifestations in 216 patients. Vasa. 1997;26:261-270.

- Yi ES, Colby TV. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2001 Feb;18(1):34-46.