User login

The current state of antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes: The data and the real world

The final event leading to acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is spontaneous atherosclerotic plaque rupture. This event is analogous to the plaque rupture caused by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Both events initiate a platelet response that starts with the adhesion of platelets to the vessel wall, followed by the activation and then aggregation of platelets.

The clinical consequences of intravascular platelet activation and aggregation are well known: death, myocardial infarction (MI), myocardial ischemia, and arrhythmias. In terms of health care burden, ACS is the primary or secondary diagnosis in 1.57 million hospitalizations annually in the United States—specifically, unstable angina or MI without ST-segment elevation in 1.24 million hospitalizations, and MI with ST-segment elevation in 330,000 hospitalizations.1

This real-world impact of ACS is tempered by the real-world use and effectiveness of our antiplatelet drug therapies, which is the focus of this article. I begin with a brief review of the evidence surrounding three major antiplatelet therapies used in ACS management—aspirin, clopidogrel, and the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. I then review the updated evidence-based guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapies in ACS. I conclude with an overview of how US hospitals are actually using these therapies, with a focus on two particularly important challenges—bleeding risk and appropriate dosing—and on initiatives under way to bridge the gap between recommended antiplatelet therapy for ACS and actual clinical practice.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY IN ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

Aspirin

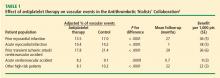

Although aspirin has long been the bedrock of antiplatelet therapy in patients with ACS, its effects on the heart are still being elucidated. Several placebo-controlled trials of aspirin, each with relatively few subjects, have been conducted in the setting of ACS without ST-segment elevation.2–5 Although confidence intervals were wide, these studies showed a favorable effect of aspirin relative to placebo on the risk of death and nonfatal MI.

Clopidogrel and dual antiplatelet therapy

CURE trial: prevention of recurrent events in patients with ACS. Dual antiplatelet therapy with the thienopyridine agent clopidogrel plus aspirin was investigated in patients presenting with ACS without ST-segment elevation in the landmark CURE trial (Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events).7 This study randomized 12,562 patients presenting within 24 hours of ACS symptom onset to either clopidogrel or placebo, in addition to aspirin, for 3 to 12 months. Clopidogrel was administered as a loading dose of 300 mg followed by a maintenance dosage of 75 mg/day. Randomization to clopidogrel was associated with a highly significant 20% relative reduction in the primary end point, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke at 12 months (9.3% incidence with clopidogrel vs 11.4% with placebo; P = .00009). Despite this impressive reduction in ischemic events with clopidogrel, the cumulative event rate continued to increase over the course of the 12-month trial in both study arms. This persistent recurrence of ischemic and thrombotic events has been observed in all antiplatelet trials to date, in spite of the addition of more potent antiplatelet regimens.

Two subanalyses of the CURE results yielded further insights. One analysis examined the timing of benefit from clopidogrel, finding that benefit emerged within 24 hours of treatment and continued consistently throughout the study’s follow-up period (mean of 9 months), supporting the notion of both early and late benefit from more potent antiplatelet therapy in ACS.8 A separate subgroup analysis found that the efficacy advantage of clopidogrel plus aspirin over aspirin alone was similar regardless of whether patients were managed medically or underwent revascularization (PCI or coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG]).9

CHARISMA trial: prevention of events in a broad at-risk population. Several years before the CURE trial, clopidogrel was initially evaluated as monotherapy in patients with prior ischemic events in the large randomized trial known as CAPRIE (Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events), in which aspirin was the comparator.10 Rates of the primary end point—a composite of vascular death, MI, or stroke—over a mean follow-up of 1.9 years were 5.3% in patients assigned to clopidogrel versus 5.8% in those assigned to aspirin, a relative reduction of 8.7% in favor of clopidogrel (P = .043).

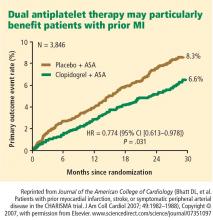

The CAPRIE study set the stage for CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance), which set out to determine whether dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel plus aspirin conferred benefit over aspirin alone in a broad population of patients at high risk for atherothrombotic events.11 No significant additive benefit was observed with dual antiplatelet therapy in the overall CHARISMA population in terms of the composite end point of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death over the median follow-up of 27.6 months.11

The investigators then analyzed outcomes in a large subgroup of the CHARISMA population—the 9,478 patients who had established vascular disease, ie, prior MI, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease.12 Rates of the composite end point (MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death) in this subgroup were 7.3% with clopidogrel plus aspirin versus 8.8% with aspirin alone, representing a 1.5% absolute reduction and a 17% relative reduction with dual antiplatelet therapy (P = .01). The CHARISMA investigators concluded that there appears to be a gradient of benefit from dual antiplatelet therapy depending on the patient’s risk of thrombotic events.

Importance of longer-term therapy. Similarly, additional recent data indicate that interrupting clopidogrel therapy leads to an abrupt increase in risk among patients who experienced ACS months beforehand. Analysis of a large registry of medically treated patients and revascularized patients with ACS showed a clustering of adverse cardiovascular events in the first 90 days after clopidogrel discontinuation, an increase that was particularly pronounced in the medically treated patients.13 Like the findings from the CHARISMA subanalysis above, these data suggest that continuing clopidogrel therapy beyond 1 year may be beneficial, although the ideal duration of therapy and the patient groups most likely to benefit requires further study.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

The glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors—abciximab, eptifibatide, and tirofiban—are parenteral drugs that block the final common pathway of platelet aggregation. With increased focus on the upstream inhibition of platelet activation and the wider availability of more potent oral antiplatelet drugs, the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors has been declining in recent years.

Efficacy in ACS. A number of placebo-controlled trials of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors have been conducted in the setting of ACS without ST-segment elevation. In each trial, the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor was associated with a significant reduction in 30-day rates of a composite of death and nonfatal MI. A 2002 pooled analysis of these trials demonstrated an overall 8% relative risk reduction in this end point with active glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy (P = .037).14 Interpreting the benefit of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade in the setting of clopidogrel therapy, however, is more challenging since upstream use of clopidogrel was rare at the time these studies were performed.

An outlier in the aforementioned pooled analysis was the GUSTO IV-ACS study (Global Utilization of Strategies to open Occluded coronary arteries trial IV in Acute Coronary Syndromes), in which abciximab showed no significant benefit over placebo on the primary end point of death or MI at 30 days.15 This study included 7,800 patients with ACS without ST-segment elevation who were being treated with aspirin and unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin and were then randomized to placebo or abciximab. Abciximab was given as a front-loaded bolus followed by an infusion lasting either 24 or 48 hours.

A trend toward higher all-cause mortality was observed with longer infusions of abciximab in the GUSTO IV-ACS trial.15 A hypothesis emerged that a front-loaded regimen of abciximab is suitable for patients undergoing PCI, in whom platelet activation and the risk of adverse outcomes is greatest in the catheterization laboratory, but is less well suited for medically managed patients, in whom levels of platelet aggregation and risk are ongoing.

Timing of treatment. The optimal timing of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor initiation remains controversial. Boersma et al pooled data from three randomized placebo-controlled trials and stratified the results into outcomes before PCI and outcomes immediately following PCI.16 Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition was associated with a 34% relative reduction in the risk of death or MI during 72 hours of medical management prior to PCI (P = .001) and an enhanced 41% relative reduction in this end point in the 48 hours following PCI when PCI was performed during administration of the study drug (P = .001). The investigators concluded that glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade should be initiated early after hospital admission and continued until after PCI in patients who undergo the procedure.

The effect of upstream glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use was more ambiguous in the recent Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy (ACUITY) trial of patients with ACS being managed invasively. At 1 year, upstream use—as compared with in-lab use—of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was associated with a reduction in the rate of ischemic events among patients treated with the direct thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin (17.4% vs 21.5%, respectively; P < .01) but not among patients treated with unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin (17.2% vs 18.4%; P = .44).17

Ongoing clinical trial results may shed further light on the considerable clinical uncertainty that remains regarding the benefits of upstream glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use in patients with ACS.

Enrollment has just been completed in a large randomized trial designed to prospectively assess the optimal timing of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor initiation in patients with high-risk ACS without ST-segment elevation in whom an invasive strategy is planned no sooner than the next calendar day.18 The study, known as EARLY-ACS, is randomizing patients to eptifibatide or placebo begun within 8 hours of hospital arrival, with provisional eptifibatide available in the catheterization laboratory. The primary end point is a 96-hour composite of all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, recurrent ischemia requiring urgent revascularization, or need for thrombotic bailout with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor during PCI. Data should be available in 2009.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY GUIDELINES IN NON-ST-ELEVATION ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

In 2007, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) updated their joint guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapy in the management of patients with unstable angina or MI without ST-segment elevation.19 These guidelines incorporate a large degree of flexibility in the choice of antiplatelet therapy, which can make implementation of their recommendations challenging.

The guidelines contain classes of recommendations based on the magnitude of benefit (I, IIa, IIb, III) and levels of evidence (A, B, C). Following here are key recommendations from the updated guidelines (bulleted and in italics, with the class and level of the recommendation noted in parentheses),19 supplemented with additional commentary where appropriate.

Antiplatelet therapy: General recommendations

- Aspirin should be given to all patients as soon as possible after presentation and continued indefinitely in patients not known to be intolerant of aspirin (class I, level A).

- Clopidogrel should be given to patients unable to take aspirin because of hypersensitivity or major gastrointestinal (GI) intolerance (class I, level A).

This recommendation is based on data from the CURE trial7 and the earlier CAPRIE study.10 The clopidogrel regimen recommended is a 300-mg loading dose followed by a maintenance dosage of 75 mg/day. The incidence of aspirin intolerance is approximately 5%, depending on how intolerance is defined. A significant proportion of patients will stop aspirin because of GI upset or trivial bleeding, failing to understand the true benefits of aspirin. A much smaller subset—perhaps 1 in 1,000—has a true allergy to aspirin.

- Patients with a history of GI bleeding with the use of either aspirin or clopidogrel should be prescribed a proton pump inhibitor or another drug that has been shown to minimize the risk of bleeding (class I, level B).

Initial invasive strategy

- For patients in whom an early invasive strategy is planned, therapy with either clopidogrel or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor should be started upstream (before diagnostic angiography) in addition to aspirin (class I, level A).

This recommendation does not give preference to either agent because head-to-head comparisons of antiplatelet and antithrombotic therapies in this setting are not available.

- Unless PCI is planned very shortly after presentation, either eptifibatide or tirofiban should be the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor of choice; if there is no appreciable delay to angiography and PCI is planned, abciximab is indicated (class I, level B).

This recommendation is based on findings of the GUSTO IV-ACS study.15

- When an initial invasive strategy is selected, initiating therapy with both clopidogrel and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor is reasonable (class IIa, level B).

Clearly, the guidelines offer some leeway to allow for different practice patterns in the use of an initial invasive strategy. In my practice, if a patient is high risk and has a low likelihood of early CABG, I use both clopidogrel and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor upstream (prior to going to the catheterization laboratory). If a patient has a reasonable likelihood of requiring CABG, I eliminate the thienopyridine and treat with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor. If a patient is at increased risk of bleeding, I forgo the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor in favor of clopidogrel.

- In patients who are going to the catheterization laboratory, omitting a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor upstream is reasonable if a loading dose of clopidogrel was given and the use of bivalirudin is planned (class IIa, level B).

This recommendation takes into account the duration of clopidogrel’s antiplatelet effect and recognizes the likely limited benefit of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients who proceed rapidly to the catheterization laboratory.

Initial conservative strategy

- In patients being managed conservatively (ie, noninvasively), clopidogrel should be given as a loading dose of at least 300 mg followed by a maintenance dosage of at least 75 mg/day, in addition to aspirin and anticoagulant therapy as soon as possible, and continued for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, up to 1 year (class I, level B).

- If patients who undergo an initial conservative management strategy have recurrent symptoms/ischemia, or if heart failure or serious arrhythmias develop, diagnostic angiography is recommended (class I, level A). Either a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (class I, level A) or clopidogrel (class I, level A) should be added to aspirin and anticoagulant therapy upstream (before angiography) in these patients (class I, level C).

- Patients classified as low risk based on stress testing should continue aspirin indefinitely (class I, level A). Clopidogrel should be continued for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, up to 1 year (class I, level B). If a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor had been started previously, it should be discontinued (class I, level A).

- Patients with coronary artery disease confirmed by angiography in whom a medical management strategy (rather than PCI) is selected should be continued on aspirin indefinitely (class I, level A). If clopidogrel has not already been started, a loading dose should be given (class I, level A). If started previously, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy should be discontinued (class I, level B).

- For patients managed medically without stenting, 75 to 162 mg/day of aspirin should be prescribed indefinitely (class I, level A), along with 75 mg/day of clopidogrel for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, for up to 1 year (class I, level B).

Antiplatelet guidelines for stenting

Antiplatelet therapy is more complicated in the setting of stenting.

- For patients in whom bare metal stents are implanted, aspirin should be prescribed at a dosage of 162 to 325 mg/day for at least 1 month (class I, level B) and then continued indefinitely at 75 to 162 mg/day (class I, level A). In addition, 75 mg/day of clopidogrel should be continued for at least 1 month and, ideally, up to 1 year unless the patient is at increased risk of bleeding (in which case it should be given for at least 2 weeks) (class I, level B).

- For patients receiving drug-eluting stents, aspirin is recommended at a dosage of 162 to 325 mg/day for at least 3 months in those with a sirolimus-eluting stent and at least 6 months in those with a paclitaxel-eluting stent, after which it should be continued indefinitely at 75 to 162 mg/day (class I, level B). In addition, clopidogrel 75 mg/day is recommended for at least 12 months regardless of the type of drug-eluting stent (class I, level B).

No mention is made of dual antiplatelet therapy beyond 1 year.

At my institution, Duke University Medical Center, patients are assessed carefully for their ability and willingness to adhere to extended antiplatelet therapy before drug-eluting stents are implanted. This assessment includes an evaluation of their insurance status, their history of adherence to other prescribed drug regimens, their education level, and the dispenser of their medications.

No guidance on concomitant anticoagulation

One omission in the current ACC/AHA guidelines is the lack of guidance for patients who require concomitant antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation. Such guidance is needed, as many patients with ACS also have indications for long-term anticoagulation, such as atrial fibrillation or valvular heart disease requiring prosthetic valves. The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend simply that anticoagulation be added to patients’ antiplatelet regimens.

HOW ARE WE DOING? APPLICATION OF GUIDELINES IN PRACTICE

No discussion of guidelines is complete without consideration of their implementation. Those interested in the use of antiplatelet therapy in ACS are fortunate to have the Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network (ACTION) Registry, a collaborative voluntary surveillance system launched in January 2007 to assess patient characteristics, treatment, and short-term outcomes in patients with ACS (MI with and without ST-segment elevation). In addition to the registry, ACTION offers guidance on measuring ACS outcomes and establishing programs for implementing evidence-based guideline recommendations in clinical practice, improving the quality and safety of ACS care, and potentially investigating novel quality-improvement methods.20

Findings from ACTION’s first 12 months

In its first 12 months (January–December 2007), the ACTION Registry captured data from 31,036 ACS cases from several hundred US hospitals, according to the ACTION National Cardiovascular Data Registry Annual Report (personal communication from Matthew T. Roe, MD, September 2008). Data were collected at two time points: acutely (during the first 24 hours after presentation) and at hospital discharge. One caveat to interpreting data from the ACTION Registry is the voluntary and retrospective reporting system on which it relies.

Intervention rates. Among patients with non-ST-segment MI in whom catheterization was not contraindicated, 85% underwent catheterization and 70% did so within 48 hours of presentation; 53% underwent PCI and 45% did so within 48 hours of presentation; and 13% underwent CABG. The median time to catheterization was 21 hours, and the median time to PCI was 19 hours.

Although many patients who go to the catheterization laboratory are managed invasively, many do not undergo PCI and are managed medically or with CABG following coronary angiography. The message, therefore, is that local practice patterns should be taken into consideration when results from clinical trials are applied to clinical practice.

Acute antiplatelet therapy. The 2007 ACTION Registry data showed that aspirin was used acutely (< 24 hours) in almost all patients in whom it was not contraindicated (97%), clopidogrel was used in 59%, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used in 44%. Given the ACC/AHA guidelines’ strong endorsement (class I, level A) of clopidogrel in this setting, one would expect wider use of clopidogrel in this context. Moreover, this relatively low rate of clopidogrel use (59%) cannot be explained by use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors instead, since this rate comprises patients who received clopidogrel either with or without a concomitant glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; only 12% of patients received a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor without clopidogrel. In contrast, a full 28% of patients received neither clopidogrel nor a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, contrary to current ACC/AHA guideline recommendations.

Antiplatelet therapy at discharge. At discharge, 97% of ACTION Registry patients were being treated with aspirin and 73% with clopidogrel. Notably, the use of clopidogrel at discharge was highly correlated with overall management strategy: whereas it was used in 97% of patients undergoing PCI, it was used in only 53% of patients being managed medically and in 31% of those undergoing CABG. These findings are somewhat reassuring since they generally mirror the strength of evidence supporting clopidogrel use in these different settings.

IMPORTANT REAL-WORLD CONSIDERATIONS: BLEEDING AND DOSING

Do not neglect bleeding risk

As antiplatelet therapy becomes more potent in an effort to reduce ischemic events, bleeding risk has become a concern. Major bleeding events occur in more than 10% of patients with ACS receiving antiplatelet therapy,21 although lower rates have been reported in clinical trials in which carefully selected populations are enrolled.7,14,22–24

Major bleeding affects overall outcomes. Major bleeding has clinical significance. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE), which analyzed data from 24,000 patients with ACS, revealed that major bleeding was associated with significantly worse outcomes: rates of in-hospital death were three times as high—15.3% versus 5.3%—in patients who had major bleeding episodes compared with those who did not (odds ratio = 1.64 [95% CI, 1.18–2.28]).25 The relationship between bleeding and adverse overall outcomes is not fully understood but is nevertheless real and has been observed in multiple databases.

Risk factors for bleeding mirror those for ischemic events. Models are currently being developed to predict bleeding. Unfortunately, the factors that predict bleeding tend to also predict recurrent ischemic events. As a result, patients who stand to benefit most from antithrombotic therapies also are at the greatest risk of bleeding from those therapies.

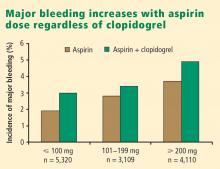

Additive risk from dual antiplatelet therapy. The additional bleeding risk from adding clopidogrel to aspirin is often not fully appreciated. In the CURE trial, the absolute excess risk of major bleeding by adding clopidogrel to aspirin was 1% (3.7% vs 2.7%), which translates to a 35% relative increase compared with aspirin alone.7 In that trial, major bleeding was most prevalent in patients undergoing CABG, and the rate of major bleeding was increased by more than 50% in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy when clopidogrel was discontinued 5 days or less before CABG (compared with CABG patients randomized to aspirin alone). This prompted the recommendation that clopidogrel be discontinued more than 5 days prior to CABG.

Similarly, the CHARISMA trial, which used the GUSTO scale for bleeding classification, revealed a significant excess of moderate bleeding with the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin relative to aspirin alone (2.1% vs 1.3%; P < .001) and a nonsignificant trend toward an excess of GUSTO-defined severe bleeding.11

Dosing: Time to end ‘one size fits all’ approach

Dosing of antiplatelet therapies has traditionally been a “one size fits all” strategy, but the importance of tailored therapy and dosing is starting to be realized.

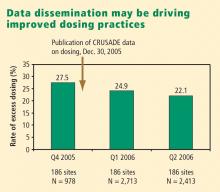

Excess dosing of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors is common, dangerous. As an example, the CRUSADE initiative, an ongoing national database of patients with high-risk ACS without ST-segment elevation, showed that 27% of patients treated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors at 400 participating US hospitals in 2004 were overdosed, based on dose-adjustment recommendations in the medications’ package inserts.27 Patients who received excessive doses were significantly more likely to suffer major bleeding than were those who were dosed correctly (odds ratio = 1.46 [95% CI, 1.22–1.73]), an increased risk that was particularly pronounced in women.

Quality-improvement initiatives. The above-mentioned CRUSADE initiative, which was launched in 2001 and involves hundreds of participating US hospitals, has served as a road map for improving dosing practices in antithrombotic therapy. Like the newer ACTION Registry,20 CRUSADE issued performance report cards to its participating hospitals in which antithrombotic medication use over the prior 12 months was compared with each institution’s past performance and with data from similar hospitals across the nation.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Managing antiplatelet therapy for patients with ACS is complex, given the array of medications available and the various combinations in which they can be used. Therapy is likely to become even more complicated, as several new medications are under review by the US Food and Drug Administration or in phase 3 clinical trials.

Current antiplatelet therapy for patients with ACS is suboptimal. Ischemic event recurrence rates continue to rise despite the use of current antiplatelet therapies, bleeding remains an underappreciated risk, and dosing often varies from evidence-based recommendations. Developing prospective strategies for antiplatelet therapy will improve utilization in keeping with a more evidence-based approach. Current ACC/AHA guidelines are the beginning of a roadmap to optimal use of antiplatelet drugs, and quality-improvement initiatives linked to national registries like ACTION promise even more guidance toward optimal therapy through institution-specific benchmarking and performance reports.

Thus far, more effective antiplatelet therapy has led to a greater risk of bleeding. Emerging novel antiplatelet agents and smarter use of existing therapies have the potential to improve both ischemic and bleeding outcomes.

- Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2007; 115:e69–e171.

- Cairns JA, Gent M, Singer J, et al. Aspirin, sulfinpyrazone, or both in unstable angina: results of a Canadian multicenter trial. N Engl J Med 1985; 313:1369–1375.

- Lewis HD Jr, Davis JW, Archibald DG, et al. Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina: results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med 1983; 309:396–403.

- Théroux P, Ouimet H, McCans J, et al. Aspirin, heparin, or both to treat acute unstable angina. N Engl J Med 1988; 319:1105–1111.

- Wallentin LC. Aspirin (75 mg/day) after an episode of unstable coronary artery disease: long-term effects on the risk for myocardial infarction, occurrence of severe angina and the need for revascularization: Research Group on Instability in Coronary Artery Disease in Southeast Sweden. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 18:1587–1593.

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002; 324:71–86.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:494–502.

- Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Zhao F, et al. Early and late effects of clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2003; 107:966–972.

- Fox KA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoing surgical revascularization for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent ischemic Events (CURE) Trial. Circulation 2004; 110:1202–1208.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomized, blinded trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996; 348:1329–1339.

- Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1706–1717.

- Bhatt DL, Flather MD, Hacke W, et al. Patients with prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:1982–1988.

- Ho PM, Peterson ED, Wang L, et al. Incidence of death and acute myocardial infarction associated with stopping clopidogrel after acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 2008; 299:532–539.

- Boersma E, Harrington RA, Moliterno DJ, et al. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of all major randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2002; 359:189–198.

- Simoons ML, GUSTO IV-ACS Investigators. Effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blocker abciximab on outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes without early coronary revascularisation: the GUSTO IV-ACS randomised trial. Lancet 2001; 357:1915–1924.

- Boersma E, Akkerhuis KM, Théroux P, Calif RM, Topol EJ, Simoons ML. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibition in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: early benefit during medical treatment only, with additional protection during percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 1999; 100:2045–2048.

- White HD, Ohman EM, Lincoff AM, et al. Safety and efficacy of bivalirudin with and without glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52:807–814.

- EARLY-ACS: glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Clinical Trials.gov Web site. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00089895. Updated December 17, 2008. Accessed December 18, 2008.

- Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:e1–e157.

- ACTION Registry–GWTG. National Cardiovascular Data Registry Web site. http://www.ncdr.com/WebNCDR/Action/default.aspx. Accessed December 22, 2008.

- Alexander KP, Chen AY, Roe MT, et al. Excess dosing of antiplatelet and antithrombin agents in the treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2005; 294:3108–3116.

- Cohen M, Demers C, Gurfinkel EP, et al. A comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin with unfractionated heparin for unstable coronary artery disease: Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q-Wave Coronary Events Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:447–452.

- Petersen JL, Mahaffey KW, Hasselblad V, et al. Efficacy and bleeding complications among patients randomized to enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin for antithrombin therapy in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a systematic overview. JAMA 2004; 292:89–96.

- The PURSUIT Trial Investigators. Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa with eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:436–443.

- Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J 2003; 24:1815–1823.

- Peters RJ, Mehta SR, Fox KA, et al. Effects of aspirin dose when used alone or in combination with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: observations from the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) study. Circulation 2003; 108:1682–1687.

- Alexander KP, Chen AY, Newby LK, et al. Sex differences in major bleeding with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: results from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) initiative. Circulation 2006; 114:1380–1387.

- Alexander KP, Chen AY, Roe MT, et al. Excess dosing of antiplatelet and antithrombin agents in the treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2005; 294:3108–3116.

- Alexander KP, Chen AY, Roe MT, et al. Decline in GP 2b3a inhibitor overdosing with site-specific feedback in CRUSADE [AHA abstract 3527]. Circulation 2007; 116:II_798–II_799.

The final event leading to acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is spontaneous atherosclerotic plaque rupture. This event is analogous to the plaque rupture caused by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Both events initiate a platelet response that starts with the adhesion of platelets to the vessel wall, followed by the activation and then aggregation of platelets.

The clinical consequences of intravascular platelet activation and aggregation are well known: death, myocardial infarction (MI), myocardial ischemia, and arrhythmias. In terms of health care burden, ACS is the primary or secondary diagnosis in 1.57 million hospitalizations annually in the United States—specifically, unstable angina or MI without ST-segment elevation in 1.24 million hospitalizations, and MI with ST-segment elevation in 330,000 hospitalizations.1

This real-world impact of ACS is tempered by the real-world use and effectiveness of our antiplatelet drug therapies, which is the focus of this article. I begin with a brief review of the evidence surrounding three major antiplatelet therapies used in ACS management—aspirin, clopidogrel, and the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. I then review the updated evidence-based guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapies in ACS. I conclude with an overview of how US hospitals are actually using these therapies, with a focus on two particularly important challenges—bleeding risk and appropriate dosing—and on initiatives under way to bridge the gap between recommended antiplatelet therapy for ACS and actual clinical practice.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY IN ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

Aspirin

Although aspirin has long been the bedrock of antiplatelet therapy in patients with ACS, its effects on the heart are still being elucidated. Several placebo-controlled trials of aspirin, each with relatively few subjects, have been conducted in the setting of ACS without ST-segment elevation.2–5 Although confidence intervals were wide, these studies showed a favorable effect of aspirin relative to placebo on the risk of death and nonfatal MI.

Clopidogrel and dual antiplatelet therapy

CURE trial: prevention of recurrent events in patients with ACS. Dual antiplatelet therapy with the thienopyridine agent clopidogrel plus aspirin was investigated in patients presenting with ACS without ST-segment elevation in the landmark CURE trial (Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events).7 This study randomized 12,562 patients presenting within 24 hours of ACS symptom onset to either clopidogrel or placebo, in addition to aspirin, for 3 to 12 months. Clopidogrel was administered as a loading dose of 300 mg followed by a maintenance dosage of 75 mg/day. Randomization to clopidogrel was associated with a highly significant 20% relative reduction in the primary end point, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke at 12 months (9.3% incidence with clopidogrel vs 11.4% with placebo; P = .00009). Despite this impressive reduction in ischemic events with clopidogrel, the cumulative event rate continued to increase over the course of the 12-month trial in both study arms. This persistent recurrence of ischemic and thrombotic events has been observed in all antiplatelet trials to date, in spite of the addition of more potent antiplatelet regimens.

Two subanalyses of the CURE results yielded further insights. One analysis examined the timing of benefit from clopidogrel, finding that benefit emerged within 24 hours of treatment and continued consistently throughout the study’s follow-up period (mean of 9 months), supporting the notion of both early and late benefit from more potent antiplatelet therapy in ACS.8 A separate subgroup analysis found that the efficacy advantage of clopidogrel plus aspirin over aspirin alone was similar regardless of whether patients were managed medically or underwent revascularization (PCI or coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG]).9

CHARISMA trial: prevention of events in a broad at-risk population. Several years before the CURE trial, clopidogrel was initially evaluated as monotherapy in patients with prior ischemic events in the large randomized trial known as CAPRIE (Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events), in which aspirin was the comparator.10 Rates of the primary end point—a composite of vascular death, MI, or stroke—over a mean follow-up of 1.9 years were 5.3% in patients assigned to clopidogrel versus 5.8% in those assigned to aspirin, a relative reduction of 8.7% in favor of clopidogrel (P = .043).

The CAPRIE study set the stage for CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance), which set out to determine whether dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel plus aspirin conferred benefit over aspirin alone in a broad population of patients at high risk for atherothrombotic events.11 No significant additive benefit was observed with dual antiplatelet therapy in the overall CHARISMA population in terms of the composite end point of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death over the median follow-up of 27.6 months.11

The investigators then analyzed outcomes in a large subgroup of the CHARISMA population—the 9,478 patients who had established vascular disease, ie, prior MI, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease.12 Rates of the composite end point (MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death) in this subgroup were 7.3% with clopidogrel plus aspirin versus 8.8% with aspirin alone, representing a 1.5% absolute reduction and a 17% relative reduction with dual antiplatelet therapy (P = .01). The CHARISMA investigators concluded that there appears to be a gradient of benefit from dual antiplatelet therapy depending on the patient’s risk of thrombotic events.

Importance of longer-term therapy. Similarly, additional recent data indicate that interrupting clopidogrel therapy leads to an abrupt increase in risk among patients who experienced ACS months beforehand. Analysis of a large registry of medically treated patients and revascularized patients with ACS showed a clustering of adverse cardiovascular events in the first 90 days after clopidogrel discontinuation, an increase that was particularly pronounced in the medically treated patients.13 Like the findings from the CHARISMA subanalysis above, these data suggest that continuing clopidogrel therapy beyond 1 year may be beneficial, although the ideal duration of therapy and the patient groups most likely to benefit requires further study.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

The glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors—abciximab, eptifibatide, and tirofiban—are parenteral drugs that block the final common pathway of platelet aggregation. With increased focus on the upstream inhibition of platelet activation and the wider availability of more potent oral antiplatelet drugs, the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors has been declining in recent years.

Efficacy in ACS. A number of placebo-controlled trials of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors have been conducted in the setting of ACS without ST-segment elevation. In each trial, the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor was associated with a significant reduction in 30-day rates of a composite of death and nonfatal MI. A 2002 pooled analysis of these trials demonstrated an overall 8% relative risk reduction in this end point with active glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy (P = .037).14 Interpreting the benefit of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade in the setting of clopidogrel therapy, however, is more challenging since upstream use of clopidogrel was rare at the time these studies were performed.

An outlier in the aforementioned pooled analysis was the GUSTO IV-ACS study (Global Utilization of Strategies to open Occluded coronary arteries trial IV in Acute Coronary Syndromes), in which abciximab showed no significant benefit over placebo on the primary end point of death or MI at 30 days.15 This study included 7,800 patients with ACS without ST-segment elevation who were being treated with aspirin and unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin and were then randomized to placebo or abciximab. Abciximab was given as a front-loaded bolus followed by an infusion lasting either 24 or 48 hours.

A trend toward higher all-cause mortality was observed with longer infusions of abciximab in the GUSTO IV-ACS trial.15 A hypothesis emerged that a front-loaded regimen of abciximab is suitable for patients undergoing PCI, in whom platelet activation and the risk of adverse outcomes is greatest in the catheterization laboratory, but is less well suited for medically managed patients, in whom levels of platelet aggregation and risk are ongoing.

Timing of treatment. The optimal timing of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor initiation remains controversial. Boersma et al pooled data from three randomized placebo-controlled trials and stratified the results into outcomes before PCI and outcomes immediately following PCI.16 Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition was associated with a 34% relative reduction in the risk of death or MI during 72 hours of medical management prior to PCI (P = .001) and an enhanced 41% relative reduction in this end point in the 48 hours following PCI when PCI was performed during administration of the study drug (P = .001). The investigators concluded that glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade should be initiated early after hospital admission and continued until after PCI in patients who undergo the procedure.

The effect of upstream glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use was more ambiguous in the recent Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy (ACUITY) trial of patients with ACS being managed invasively. At 1 year, upstream use—as compared with in-lab use—of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was associated with a reduction in the rate of ischemic events among patients treated with the direct thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin (17.4% vs 21.5%, respectively; P < .01) but not among patients treated with unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin (17.2% vs 18.4%; P = .44).17

Ongoing clinical trial results may shed further light on the considerable clinical uncertainty that remains regarding the benefits of upstream glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use in patients with ACS.

Enrollment has just been completed in a large randomized trial designed to prospectively assess the optimal timing of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor initiation in patients with high-risk ACS without ST-segment elevation in whom an invasive strategy is planned no sooner than the next calendar day.18 The study, known as EARLY-ACS, is randomizing patients to eptifibatide or placebo begun within 8 hours of hospital arrival, with provisional eptifibatide available in the catheterization laboratory. The primary end point is a 96-hour composite of all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, recurrent ischemia requiring urgent revascularization, or need for thrombotic bailout with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor during PCI. Data should be available in 2009.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY GUIDELINES IN NON-ST-ELEVATION ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

In 2007, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) updated their joint guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapy in the management of patients with unstable angina or MI without ST-segment elevation.19 These guidelines incorporate a large degree of flexibility in the choice of antiplatelet therapy, which can make implementation of their recommendations challenging.

The guidelines contain classes of recommendations based on the magnitude of benefit (I, IIa, IIb, III) and levels of evidence (A, B, C). Following here are key recommendations from the updated guidelines (bulleted and in italics, with the class and level of the recommendation noted in parentheses),19 supplemented with additional commentary where appropriate.

Antiplatelet therapy: General recommendations

- Aspirin should be given to all patients as soon as possible after presentation and continued indefinitely in patients not known to be intolerant of aspirin (class I, level A).

- Clopidogrel should be given to patients unable to take aspirin because of hypersensitivity or major gastrointestinal (GI) intolerance (class I, level A).

This recommendation is based on data from the CURE trial7 and the earlier CAPRIE study.10 The clopidogrel regimen recommended is a 300-mg loading dose followed by a maintenance dosage of 75 mg/day. The incidence of aspirin intolerance is approximately 5%, depending on how intolerance is defined. A significant proportion of patients will stop aspirin because of GI upset or trivial bleeding, failing to understand the true benefits of aspirin. A much smaller subset—perhaps 1 in 1,000—has a true allergy to aspirin.

- Patients with a history of GI bleeding with the use of either aspirin or clopidogrel should be prescribed a proton pump inhibitor or another drug that has been shown to minimize the risk of bleeding (class I, level B).

Initial invasive strategy

- For patients in whom an early invasive strategy is planned, therapy with either clopidogrel or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor should be started upstream (before diagnostic angiography) in addition to aspirin (class I, level A).

This recommendation does not give preference to either agent because head-to-head comparisons of antiplatelet and antithrombotic therapies in this setting are not available.

- Unless PCI is planned very shortly after presentation, either eptifibatide or tirofiban should be the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor of choice; if there is no appreciable delay to angiography and PCI is planned, abciximab is indicated (class I, level B).

This recommendation is based on findings of the GUSTO IV-ACS study.15

- When an initial invasive strategy is selected, initiating therapy with both clopidogrel and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor is reasonable (class IIa, level B).

Clearly, the guidelines offer some leeway to allow for different practice patterns in the use of an initial invasive strategy. In my practice, if a patient is high risk and has a low likelihood of early CABG, I use both clopidogrel and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor upstream (prior to going to the catheterization laboratory). If a patient has a reasonable likelihood of requiring CABG, I eliminate the thienopyridine and treat with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor. If a patient is at increased risk of bleeding, I forgo the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor in favor of clopidogrel.

- In patients who are going to the catheterization laboratory, omitting a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor upstream is reasonable if a loading dose of clopidogrel was given and the use of bivalirudin is planned (class IIa, level B).

This recommendation takes into account the duration of clopidogrel’s antiplatelet effect and recognizes the likely limited benefit of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients who proceed rapidly to the catheterization laboratory.

Initial conservative strategy

- In patients being managed conservatively (ie, noninvasively), clopidogrel should be given as a loading dose of at least 300 mg followed by a maintenance dosage of at least 75 mg/day, in addition to aspirin and anticoagulant therapy as soon as possible, and continued for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, up to 1 year (class I, level B).

- If patients who undergo an initial conservative management strategy have recurrent symptoms/ischemia, or if heart failure or serious arrhythmias develop, diagnostic angiography is recommended (class I, level A). Either a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (class I, level A) or clopidogrel (class I, level A) should be added to aspirin and anticoagulant therapy upstream (before angiography) in these patients (class I, level C).

- Patients classified as low risk based on stress testing should continue aspirin indefinitely (class I, level A). Clopidogrel should be continued for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, up to 1 year (class I, level B). If a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor had been started previously, it should be discontinued (class I, level A).

- Patients with coronary artery disease confirmed by angiography in whom a medical management strategy (rather than PCI) is selected should be continued on aspirin indefinitely (class I, level A). If clopidogrel has not already been started, a loading dose should be given (class I, level A). If started previously, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy should be discontinued (class I, level B).

- For patients managed medically without stenting, 75 to 162 mg/day of aspirin should be prescribed indefinitely (class I, level A), along with 75 mg/day of clopidogrel for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, for up to 1 year (class I, level B).

Antiplatelet guidelines for stenting

Antiplatelet therapy is more complicated in the setting of stenting.

- For patients in whom bare metal stents are implanted, aspirin should be prescribed at a dosage of 162 to 325 mg/day for at least 1 month (class I, level B) and then continued indefinitely at 75 to 162 mg/day (class I, level A). In addition, 75 mg/day of clopidogrel should be continued for at least 1 month and, ideally, up to 1 year unless the patient is at increased risk of bleeding (in which case it should be given for at least 2 weeks) (class I, level B).

- For patients receiving drug-eluting stents, aspirin is recommended at a dosage of 162 to 325 mg/day for at least 3 months in those with a sirolimus-eluting stent and at least 6 months in those with a paclitaxel-eluting stent, after which it should be continued indefinitely at 75 to 162 mg/day (class I, level B). In addition, clopidogrel 75 mg/day is recommended for at least 12 months regardless of the type of drug-eluting stent (class I, level B).

No mention is made of dual antiplatelet therapy beyond 1 year.

At my institution, Duke University Medical Center, patients are assessed carefully for their ability and willingness to adhere to extended antiplatelet therapy before drug-eluting stents are implanted. This assessment includes an evaluation of their insurance status, their history of adherence to other prescribed drug regimens, their education level, and the dispenser of their medications.

No guidance on concomitant anticoagulation

One omission in the current ACC/AHA guidelines is the lack of guidance for patients who require concomitant antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation. Such guidance is needed, as many patients with ACS also have indications for long-term anticoagulation, such as atrial fibrillation or valvular heart disease requiring prosthetic valves. The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend simply that anticoagulation be added to patients’ antiplatelet regimens.

HOW ARE WE DOING? APPLICATION OF GUIDELINES IN PRACTICE

No discussion of guidelines is complete without consideration of their implementation. Those interested in the use of antiplatelet therapy in ACS are fortunate to have the Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network (ACTION) Registry, a collaborative voluntary surveillance system launched in January 2007 to assess patient characteristics, treatment, and short-term outcomes in patients with ACS (MI with and without ST-segment elevation). In addition to the registry, ACTION offers guidance on measuring ACS outcomes and establishing programs for implementing evidence-based guideline recommendations in clinical practice, improving the quality and safety of ACS care, and potentially investigating novel quality-improvement methods.20

Findings from ACTION’s first 12 months

In its first 12 months (January–December 2007), the ACTION Registry captured data from 31,036 ACS cases from several hundred US hospitals, according to the ACTION National Cardiovascular Data Registry Annual Report (personal communication from Matthew T. Roe, MD, September 2008). Data were collected at two time points: acutely (during the first 24 hours after presentation) and at hospital discharge. One caveat to interpreting data from the ACTION Registry is the voluntary and retrospective reporting system on which it relies.

Intervention rates. Among patients with non-ST-segment MI in whom catheterization was not contraindicated, 85% underwent catheterization and 70% did so within 48 hours of presentation; 53% underwent PCI and 45% did so within 48 hours of presentation; and 13% underwent CABG. The median time to catheterization was 21 hours, and the median time to PCI was 19 hours.

Although many patients who go to the catheterization laboratory are managed invasively, many do not undergo PCI and are managed medically or with CABG following coronary angiography. The message, therefore, is that local practice patterns should be taken into consideration when results from clinical trials are applied to clinical practice.

Acute antiplatelet therapy. The 2007 ACTION Registry data showed that aspirin was used acutely (< 24 hours) in almost all patients in whom it was not contraindicated (97%), clopidogrel was used in 59%, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used in 44%. Given the ACC/AHA guidelines’ strong endorsement (class I, level A) of clopidogrel in this setting, one would expect wider use of clopidogrel in this context. Moreover, this relatively low rate of clopidogrel use (59%) cannot be explained by use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors instead, since this rate comprises patients who received clopidogrel either with or without a concomitant glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; only 12% of patients received a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor without clopidogrel. In contrast, a full 28% of patients received neither clopidogrel nor a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, contrary to current ACC/AHA guideline recommendations.

Antiplatelet therapy at discharge. At discharge, 97% of ACTION Registry patients were being treated with aspirin and 73% with clopidogrel. Notably, the use of clopidogrel at discharge was highly correlated with overall management strategy: whereas it was used in 97% of patients undergoing PCI, it was used in only 53% of patients being managed medically and in 31% of those undergoing CABG. These findings are somewhat reassuring since they generally mirror the strength of evidence supporting clopidogrel use in these different settings.

IMPORTANT REAL-WORLD CONSIDERATIONS: BLEEDING AND DOSING

Do not neglect bleeding risk

As antiplatelet therapy becomes more potent in an effort to reduce ischemic events, bleeding risk has become a concern. Major bleeding events occur in more than 10% of patients with ACS receiving antiplatelet therapy,21 although lower rates have been reported in clinical trials in which carefully selected populations are enrolled.7,14,22–24

Major bleeding affects overall outcomes. Major bleeding has clinical significance. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE), which analyzed data from 24,000 patients with ACS, revealed that major bleeding was associated with significantly worse outcomes: rates of in-hospital death were three times as high—15.3% versus 5.3%—in patients who had major bleeding episodes compared with those who did not (odds ratio = 1.64 [95% CI, 1.18–2.28]).25 The relationship between bleeding and adverse overall outcomes is not fully understood but is nevertheless real and has been observed in multiple databases.

Risk factors for bleeding mirror those for ischemic events. Models are currently being developed to predict bleeding. Unfortunately, the factors that predict bleeding tend to also predict recurrent ischemic events. As a result, patients who stand to benefit most from antithrombotic therapies also are at the greatest risk of bleeding from those therapies.

Additive risk from dual antiplatelet therapy. The additional bleeding risk from adding clopidogrel to aspirin is often not fully appreciated. In the CURE trial, the absolute excess risk of major bleeding by adding clopidogrel to aspirin was 1% (3.7% vs 2.7%), which translates to a 35% relative increase compared with aspirin alone.7 In that trial, major bleeding was most prevalent in patients undergoing CABG, and the rate of major bleeding was increased by more than 50% in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy when clopidogrel was discontinued 5 days or less before CABG (compared with CABG patients randomized to aspirin alone). This prompted the recommendation that clopidogrel be discontinued more than 5 days prior to CABG.

Similarly, the CHARISMA trial, which used the GUSTO scale for bleeding classification, revealed a significant excess of moderate bleeding with the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin relative to aspirin alone (2.1% vs 1.3%; P < .001) and a nonsignificant trend toward an excess of GUSTO-defined severe bleeding.11

Dosing: Time to end ‘one size fits all’ approach

Dosing of antiplatelet therapies has traditionally been a “one size fits all” strategy, but the importance of tailored therapy and dosing is starting to be realized.

Excess dosing of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors is common, dangerous. As an example, the CRUSADE initiative, an ongoing national database of patients with high-risk ACS without ST-segment elevation, showed that 27% of patients treated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors at 400 participating US hospitals in 2004 were overdosed, based on dose-adjustment recommendations in the medications’ package inserts.27 Patients who received excessive doses were significantly more likely to suffer major bleeding than were those who were dosed correctly (odds ratio = 1.46 [95% CI, 1.22–1.73]), an increased risk that was particularly pronounced in women.

Quality-improvement initiatives. The above-mentioned CRUSADE initiative, which was launched in 2001 and involves hundreds of participating US hospitals, has served as a road map for improving dosing practices in antithrombotic therapy. Like the newer ACTION Registry,20 CRUSADE issued performance report cards to its participating hospitals in which antithrombotic medication use over the prior 12 months was compared with each institution’s past performance and with data from similar hospitals across the nation.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Managing antiplatelet therapy for patients with ACS is complex, given the array of medications available and the various combinations in which they can be used. Therapy is likely to become even more complicated, as several new medications are under review by the US Food and Drug Administration or in phase 3 clinical trials.

Current antiplatelet therapy for patients with ACS is suboptimal. Ischemic event recurrence rates continue to rise despite the use of current antiplatelet therapies, bleeding remains an underappreciated risk, and dosing often varies from evidence-based recommendations. Developing prospective strategies for antiplatelet therapy will improve utilization in keeping with a more evidence-based approach. Current ACC/AHA guidelines are the beginning of a roadmap to optimal use of antiplatelet drugs, and quality-improvement initiatives linked to national registries like ACTION promise even more guidance toward optimal therapy through institution-specific benchmarking and performance reports.

Thus far, more effective antiplatelet therapy has led to a greater risk of bleeding. Emerging novel antiplatelet agents and smarter use of existing therapies have the potential to improve both ischemic and bleeding outcomes.

The final event leading to acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is spontaneous atherosclerotic plaque rupture. This event is analogous to the plaque rupture caused by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Both events initiate a platelet response that starts with the adhesion of platelets to the vessel wall, followed by the activation and then aggregation of platelets.

The clinical consequences of intravascular platelet activation and aggregation are well known: death, myocardial infarction (MI), myocardial ischemia, and arrhythmias. In terms of health care burden, ACS is the primary or secondary diagnosis in 1.57 million hospitalizations annually in the United States—specifically, unstable angina or MI without ST-segment elevation in 1.24 million hospitalizations, and MI with ST-segment elevation in 330,000 hospitalizations.1

This real-world impact of ACS is tempered by the real-world use and effectiveness of our antiplatelet drug therapies, which is the focus of this article. I begin with a brief review of the evidence surrounding three major antiplatelet therapies used in ACS management—aspirin, clopidogrel, and the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. I then review the updated evidence-based guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapies in ACS. I conclude with an overview of how US hospitals are actually using these therapies, with a focus on two particularly important challenges—bleeding risk and appropriate dosing—and on initiatives under way to bridge the gap between recommended antiplatelet therapy for ACS and actual clinical practice.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY IN ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

Aspirin

Although aspirin has long been the bedrock of antiplatelet therapy in patients with ACS, its effects on the heart are still being elucidated. Several placebo-controlled trials of aspirin, each with relatively few subjects, have been conducted in the setting of ACS without ST-segment elevation.2–5 Although confidence intervals were wide, these studies showed a favorable effect of aspirin relative to placebo on the risk of death and nonfatal MI.

Clopidogrel and dual antiplatelet therapy

CURE trial: prevention of recurrent events in patients with ACS. Dual antiplatelet therapy with the thienopyridine agent clopidogrel plus aspirin was investigated in patients presenting with ACS without ST-segment elevation in the landmark CURE trial (Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events).7 This study randomized 12,562 patients presenting within 24 hours of ACS symptom onset to either clopidogrel or placebo, in addition to aspirin, for 3 to 12 months. Clopidogrel was administered as a loading dose of 300 mg followed by a maintenance dosage of 75 mg/day. Randomization to clopidogrel was associated with a highly significant 20% relative reduction in the primary end point, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke at 12 months (9.3% incidence with clopidogrel vs 11.4% with placebo; P = .00009). Despite this impressive reduction in ischemic events with clopidogrel, the cumulative event rate continued to increase over the course of the 12-month trial in both study arms. This persistent recurrence of ischemic and thrombotic events has been observed in all antiplatelet trials to date, in spite of the addition of more potent antiplatelet regimens.

Two subanalyses of the CURE results yielded further insights. One analysis examined the timing of benefit from clopidogrel, finding that benefit emerged within 24 hours of treatment and continued consistently throughout the study’s follow-up period (mean of 9 months), supporting the notion of both early and late benefit from more potent antiplatelet therapy in ACS.8 A separate subgroup analysis found that the efficacy advantage of clopidogrel plus aspirin over aspirin alone was similar regardless of whether patients were managed medically or underwent revascularization (PCI or coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG]).9

CHARISMA trial: prevention of events in a broad at-risk population. Several years before the CURE trial, clopidogrel was initially evaluated as monotherapy in patients with prior ischemic events in the large randomized trial known as CAPRIE (Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events), in which aspirin was the comparator.10 Rates of the primary end point—a composite of vascular death, MI, or stroke—over a mean follow-up of 1.9 years were 5.3% in patients assigned to clopidogrel versus 5.8% in those assigned to aspirin, a relative reduction of 8.7% in favor of clopidogrel (P = .043).

The CAPRIE study set the stage for CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance), which set out to determine whether dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel plus aspirin conferred benefit over aspirin alone in a broad population of patients at high risk for atherothrombotic events.11 No significant additive benefit was observed with dual antiplatelet therapy in the overall CHARISMA population in terms of the composite end point of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death over the median follow-up of 27.6 months.11

The investigators then analyzed outcomes in a large subgroup of the CHARISMA population—the 9,478 patients who had established vascular disease, ie, prior MI, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease.12 Rates of the composite end point (MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death) in this subgroup were 7.3% with clopidogrel plus aspirin versus 8.8% with aspirin alone, representing a 1.5% absolute reduction and a 17% relative reduction with dual antiplatelet therapy (P = .01). The CHARISMA investigators concluded that there appears to be a gradient of benefit from dual antiplatelet therapy depending on the patient’s risk of thrombotic events.

Importance of longer-term therapy. Similarly, additional recent data indicate that interrupting clopidogrel therapy leads to an abrupt increase in risk among patients who experienced ACS months beforehand. Analysis of a large registry of medically treated patients and revascularized patients with ACS showed a clustering of adverse cardiovascular events in the first 90 days after clopidogrel discontinuation, an increase that was particularly pronounced in the medically treated patients.13 Like the findings from the CHARISMA subanalysis above, these data suggest that continuing clopidogrel therapy beyond 1 year may be beneficial, although the ideal duration of therapy and the patient groups most likely to benefit requires further study.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

The glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors—abciximab, eptifibatide, and tirofiban—are parenteral drugs that block the final common pathway of platelet aggregation. With increased focus on the upstream inhibition of platelet activation and the wider availability of more potent oral antiplatelet drugs, the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors has been declining in recent years.

Efficacy in ACS. A number of placebo-controlled trials of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors have been conducted in the setting of ACS without ST-segment elevation. In each trial, the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor was associated with a significant reduction in 30-day rates of a composite of death and nonfatal MI. A 2002 pooled analysis of these trials demonstrated an overall 8% relative risk reduction in this end point with active glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy (P = .037).14 Interpreting the benefit of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade in the setting of clopidogrel therapy, however, is more challenging since upstream use of clopidogrel was rare at the time these studies were performed.

An outlier in the aforementioned pooled analysis was the GUSTO IV-ACS study (Global Utilization of Strategies to open Occluded coronary arteries trial IV in Acute Coronary Syndromes), in which abciximab showed no significant benefit over placebo on the primary end point of death or MI at 30 days.15 This study included 7,800 patients with ACS without ST-segment elevation who were being treated with aspirin and unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin and were then randomized to placebo or abciximab. Abciximab was given as a front-loaded bolus followed by an infusion lasting either 24 or 48 hours.

A trend toward higher all-cause mortality was observed with longer infusions of abciximab in the GUSTO IV-ACS trial.15 A hypothesis emerged that a front-loaded regimen of abciximab is suitable for patients undergoing PCI, in whom platelet activation and the risk of adverse outcomes is greatest in the catheterization laboratory, but is less well suited for medically managed patients, in whom levels of platelet aggregation and risk are ongoing.

Timing of treatment. The optimal timing of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor initiation remains controversial. Boersma et al pooled data from three randomized placebo-controlled trials and stratified the results into outcomes before PCI and outcomes immediately following PCI.16 Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition was associated with a 34% relative reduction in the risk of death or MI during 72 hours of medical management prior to PCI (P = .001) and an enhanced 41% relative reduction in this end point in the 48 hours following PCI when PCI was performed during administration of the study drug (P = .001). The investigators concluded that glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade should be initiated early after hospital admission and continued until after PCI in patients who undergo the procedure.

The effect of upstream glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use was more ambiguous in the recent Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy (ACUITY) trial of patients with ACS being managed invasively. At 1 year, upstream use—as compared with in-lab use—of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was associated with a reduction in the rate of ischemic events among patients treated with the direct thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin (17.4% vs 21.5%, respectively; P < .01) but not among patients treated with unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin (17.2% vs 18.4%; P = .44).17

Ongoing clinical trial results may shed further light on the considerable clinical uncertainty that remains regarding the benefits of upstream glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use in patients with ACS.

Enrollment has just been completed in a large randomized trial designed to prospectively assess the optimal timing of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor initiation in patients with high-risk ACS without ST-segment elevation in whom an invasive strategy is planned no sooner than the next calendar day.18 The study, known as EARLY-ACS, is randomizing patients to eptifibatide or placebo begun within 8 hours of hospital arrival, with provisional eptifibatide available in the catheterization laboratory. The primary end point is a 96-hour composite of all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, recurrent ischemia requiring urgent revascularization, or need for thrombotic bailout with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor during PCI. Data should be available in 2009.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY GUIDELINES IN NON-ST-ELEVATION ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

In 2007, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) updated their joint guidelines for the use of antiplatelet therapy in the management of patients with unstable angina or MI without ST-segment elevation.19 These guidelines incorporate a large degree of flexibility in the choice of antiplatelet therapy, which can make implementation of their recommendations challenging.

The guidelines contain classes of recommendations based on the magnitude of benefit (I, IIa, IIb, III) and levels of evidence (A, B, C). Following here are key recommendations from the updated guidelines (bulleted and in italics, with the class and level of the recommendation noted in parentheses),19 supplemented with additional commentary where appropriate.

Antiplatelet therapy: General recommendations

- Aspirin should be given to all patients as soon as possible after presentation and continued indefinitely in patients not known to be intolerant of aspirin (class I, level A).

- Clopidogrel should be given to patients unable to take aspirin because of hypersensitivity or major gastrointestinal (GI) intolerance (class I, level A).

This recommendation is based on data from the CURE trial7 and the earlier CAPRIE study.10 The clopidogrel regimen recommended is a 300-mg loading dose followed by a maintenance dosage of 75 mg/day. The incidence of aspirin intolerance is approximately 5%, depending on how intolerance is defined. A significant proportion of patients will stop aspirin because of GI upset or trivial bleeding, failing to understand the true benefits of aspirin. A much smaller subset—perhaps 1 in 1,000—has a true allergy to aspirin.

- Patients with a history of GI bleeding with the use of either aspirin or clopidogrel should be prescribed a proton pump inhibitor or another drug that has been shown to minimize the risk of bleeding (class I, level B).

Initial invasive strategy

- For patients in whom an early invasive strategy is planned, therapy with either clopidogrel or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor should be started upstream (before diagnostic angiography) in addition to aspirin (class I, level A).

This recommendation does not give preference to either agent because head-to-head comparisons of antiplatelet and antithrombotic therapies in this setting are not available.

- Unless PCI is planned very shortly after presentation, either eptifibatide or tirofiban should be the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor of choice; if there is no appreciable delay to angiography and PCI is planned, abciximab is indicated (class I, level B).

This recommendation is based on findings of the GUSTO IV-ACS study.15

- When an initial invasive strategy is selected, initiating therapy with both clopidogrel and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor is reasonable (class IIa, level B).

Clearly, the guidelines offer some leeway to allow for different practice patterns in the use of an initial invasive strategy. In my practice, if a patient is high risk and has a low likelihood of early CABG, I use both clopidogrel and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor upstream (prior to going to the catheterization laboratory). If a patient has a reasonable likelihood of requiring CABG, I eliminate the thienopyridine and treat with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor. If a patient is at increased risk of bleeding, I forgo the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor in favor of clopidogrel.

- In patients who are going to the catheterization laboratory, omitting a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor upstream is reasonable if a loading dose of clopidogrel was given and the use of bivalirudin is planned (class IIa, level B).

This recommendation takes into account the duration of clopidogrel’s antiplatelet effect and recognizes the likely limited benefit of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients who proceed rapidly to the catheterization laboratory.

Initial conservative strategy

- In patients being managed conservatively (ie, noninvasively), clopidogrel should be given as a loading dose of at least 300 mg followed by a maintenance dosage of at least 75 mg/day, in addition to aspirin and anticoagulant therapy as soon as possible, and continued for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, up to 1 year (class I, level B).

- If patients who undergo an initial conservative management strategy have recurrent symptoms/ischemia, or if heart failure or serious arrhythmias develop, diagnostic angiography is recommended (class I, level A). Either a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (class I, level A) or clopidogrel (class I, level A) should be added to aspirin and anticoagulant therapy upstream (before angiography) in these patients (class I, level C).

- Patients classified as low risk based on stress testing should continue aspirin indefinitely (class I, level A). Clopidogrel should be continued for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, up to 1 year (class I, level B). If a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor had been started previously, it should be discontinued (class I, level A).

- Patients with coronary artery disease confirmed by angiography in whom a medical management strategy (rather than PCI) is selected should be continued on aspirin indefinitely (class I, level A). If clopidogrel has not already been started, a loading dose should be given (class I, level A). If started previously, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy should be discontinued (class I, level B).

- For patients managed medically without stenting, 75 to 162 mg/day of aspirin should be prescribed indefinitely (class I, level A), along with 75 mg/day of clopidogrel for at least 1 month (class I, level A) and, ideally, for up to 1 year (class I, level B).

Antiplatelet guidelines for stenting

Antiplatelet therapy is more complicated in the setting of stenting.