User login

Creating a student-staffed family call line to alleviate clinical burden

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

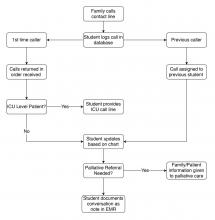

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.