User login

Better time data from in-hospital resuscitations

Benefits of an undocumented defibrillator feature

Research and quality improvement (QI) related to in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation attempts (“codes” from here forward) are hampered significantly by the poor quality of data on time intervals from arrest onset to clinical interventions.1

In 2000, the American Heart Association’s (AHA) Emergency Cardiac Care Guidelines said that current data were inaccurate and that greater accuracy was “the key to future high-quality research”2 – but since then, the general situation has not improved: Time intervals reported by the national AHA-supported registry Get With the Guidelines–Resuscitation (GWTG-R, 200+ hospitals enrolled) include a figure from all hospitals for times to first defibrillation of 1 minute median and 0 minutes first interquartile.3 Such numbers are typical – when they are tracked at all – but they strain credulity, and prima facie evidence is available at most clinical simulation centers simply by timing simulated defibrillation attempts under realistic conditions, as in “mock codes.”4,5

Taking artificially short time-interval data from GWTG-R or other sources at face value can hide serious delays in response to in-hospital arrests. It can also lead to flawed studies and highly questionable conclusions.6

The key to accuracy of critical time intervals – the intervals from arrest to key interventions – is an accurate time of arrest.7 Codes are typically recorded in handwritten form, though they may later be transcribed or scanned into electronic records. The “start” of the code for unmonitored arrests and most monitored arrests is typically taken to be the time that a human bedside recorder, arriving at an unknown interval after the arrest, writes down the first intervention. Researchers acknowledged the problem of artificially short time intervals in 2005, but they did not propose a remedy.1 Since then, the problem of in-hospital resuscitation delays has received little to no attention in the professional literature.

Description of feature

To get better time data from unmonitored resuscitation attempts, it is necessary to use a “surrogate marker” – a stand-in or substitute event – for the time of arrest. This event should occur reliably for each code, and as near as possible to the actual time of arrest. The main early events in a code are starting basic CPR, paging the code, and moving the defibrillator (usually on a code cart) to the scene. Ideally these events occur almost simultaneously, but that is not consistently achieved.

There are significant problems with use of the first two events as surrogate markers: the time of starting CPR cannot be determined accurately, and paging the code is dependent on several intermediate steps that lead to inaccuracy. Furthermore, the times of both markers are recorded using clocks that are typically not synchronized with the clock used for recording the code (defibrillator clock or the human recorder’s timepiece). Reconciliation of these times with the code record, while not particularly difficult,8 is rarely if ever done.

Defibrillator Power On is recorded on the defibrillator timeline and thus does not need to be reconciled with the defibrillator clock, but it is not suitable as a surrogate marker because this time is highly variable: It often does not occur until the time that monitoring pads are placed. Moving the code cart to the scene, which must occur early in the code, is a much more valid surrogate marker, with the added benefit that it can be marked on the defibrillator timeline.

The undocumented feature described here provides that marker. This feature has been a part of the LIFEPAK 20/20e’s design since it was launched in 2002, but it has not been publicized until now and is not documented in the user manual.

Hospital defibrillators are connected to alternating-current (AC) power when not in use. When the defibrillator is moved to the scene of the code, it is obviously necessary to disconnect the defibrillator from the wall outlet, at which time “AC Power Loss” is recorded on the event record generated by the LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators. The defibrillator may be powered on up to 10 minutes later while retaining the AC Power Loss marker in the event record. This surrogate marker for the start time will be on the same timeline as other events recorded by the defibrillator, including times of first monitoring and shocks.

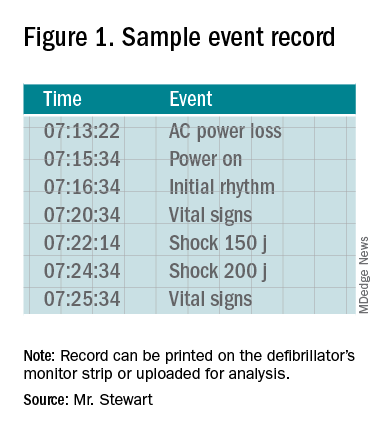

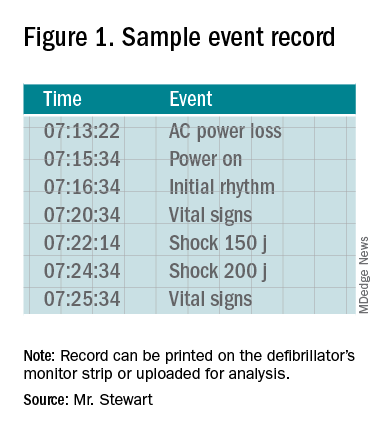

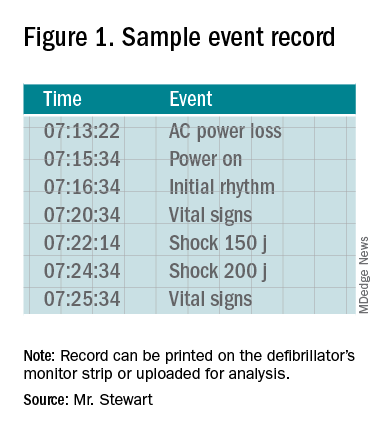

Once the event record is acquired, determining time intervals is accomplished by subtracting clock times (see example, Figure 1).

In the example, using AC Power Loss as the start time, time intervals from arrest to first monitoring (Initial Rhythm on the Event Record) and first shock were 3:12 (07:16:34 minus 07:13:22) and 8:42 (07:22:14 minus 07:13:22). Note that if Power On were used as the surrogate time of arrest in the example, the calculated intervals would be artificially shorter, by 2 min 12 sec.

Using this undocumented feature, any facility using LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators can easily measure critical time intervals during resuscitation attempts with much greater accuracy, including times to first monitoring and first defibrillation. Each defibrillator stores code summaries sufficient for dozens of events and accessing past data is simple. Analysis of the data can provide a much-improved measure of the facility’s speed of response as a baseline for QI.

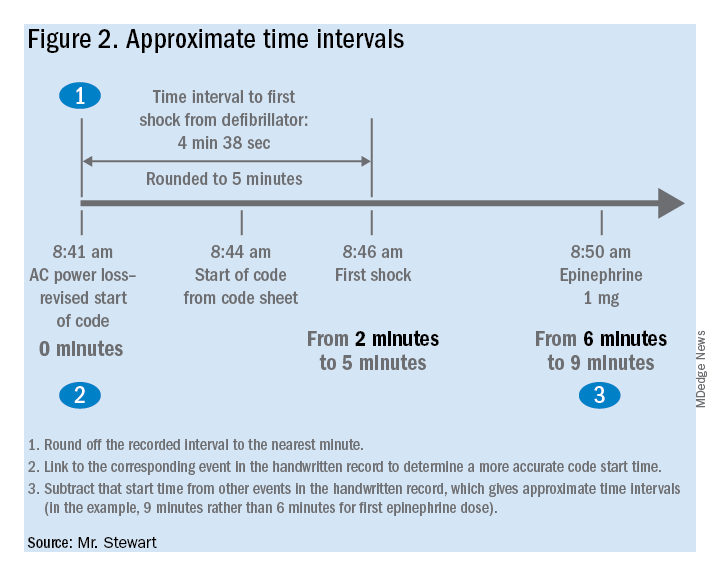

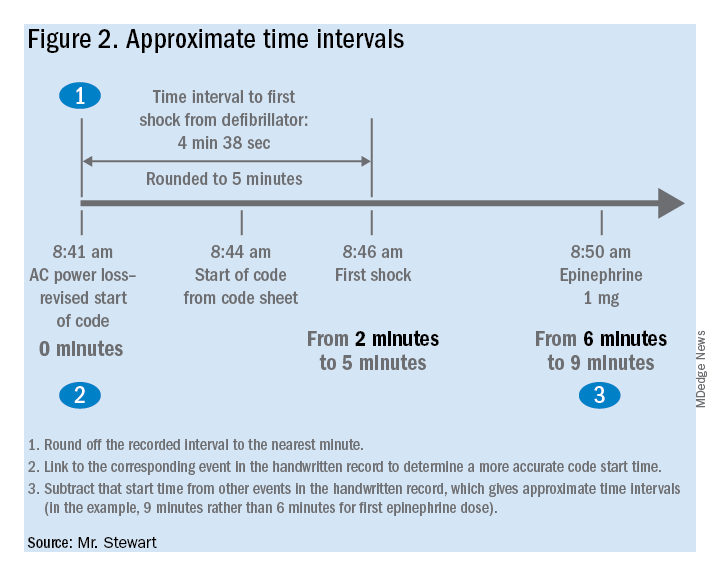

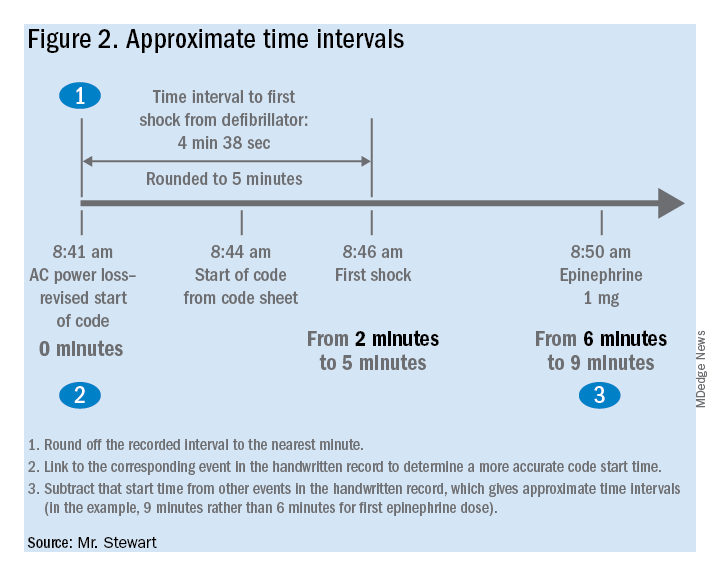

If desired, the time-interval data thus obtained can also be integrated with the handwritten record. The usual handwritten code sheet records times only in whole minutes, but with one of the more accurate intervals from the defibrillator – to first monitoring or first defibrillation – an adjusted time of arrest can be added to any code record to get other intervals that better approximate real-world response times.9

Research prospects

The feature opens multiple avenues for future research. Acquiring data by this method should be simple for any facility using LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators as its standard devices. Matching the existing handwritten code records with the time intervals obtained using this surrogate time marker will show how inaccurate the commonly reported data are. This can be done with a retrospective study comparing the time intervals from the archived event records with those from the handwritten records, to provide an example of the inaccuracy of data reported in the medical literature. The more accurate picture of time intervals can provide a much-needed yardstick for future research aimed at shortening response times.

The feature can facilitate aggregation of data across multiple facilities that use the LIFEPAK 20/20e as their standard defibrillator. Also, it is possible that other defibrillator manufacturers will duplicate this feature with their devices – it should produce valid data with any defibrillator – although there may be legal and technical obstacles to adopting it.

Combining data from multiple sites might lead to an important contribution to resuscitation research: a reasonably accurate overall survival curve for in-hospital tachyarrhythmic arrests. A commonly cited but crude guideline is that survival from tachyarrhythmic arrests decreases by 10%-15% per minute as defibrillation is delayed,10 but it seems unlikely that the relationship would be linear: Experience and the literature suggest that survival drops very quickly in the first few minutes, flattening out as elapsed time after arrest increases. Aggregating the much more accurate time-interval data from multiple facilities should produce a survival curve for in-hospital tachyarrhythmic arrests that comes much closer to reality.

Conclusion

It is unknown whether this feature will be used to improve the accuracy of reported code response times. It greatly facilitates acquiring more accurate times, but the task has never been especially difficult – particularly when balanced with the importance of better time data for QI and research.8 One possible impediment may be institutional obstacles to publishing studies with accurate response times due to concerns about public relations or legal exposure: The more accurate times will almost certainly be longer than those generally reported.

As was stated almost 2 decades ago and remains true today, acquiring accurate time-interval data is “the key to future high-quality research.”2 It is also key to improving any hospital’s quality of code response. As described in this article, better time data can easily be acquired. It is time for this important problem to be recognized and remedied.

Mr. Stewart has worked as a hospital nurse in Seattle for many years, and has numerous publications to his credit related to resuscitation issues. You can contact him at jastewart325@gmail.com.

References

1. Kaye W et al. When minutes count – the fallacy of accurate time documentation during in-hospital resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005;65(3):285-90.

2. The American Heart Association in collaboration with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, Part 4: the automated external defibrillator: key link in the chain of survival. Circulation. 2000;102(8 Suppl):I-60-76.

3. Chan PS et al. American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 3;358(1):9-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706467.

4. Hunt EA et al. Simulation of in-hospital pediatric medical emergencies and cardiopulmonary arrests: Highlighting the importance of the first 5 minutes. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e34-e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0029.

5. Reeson M et al. Defibrillator design and usability may be impeding timely defibrillation. Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018 Sep;44(9):536-544. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.01.005.

6. Hunt EA et al. American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines – Resuscitation Investigators. Association between time to defibrillation and survival in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest with a first documented shockable rhythm JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182643. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2643.

7. Cummins RO et al. Recommended guidelines for reviewing, reporting, and conducting research on in-hospital resuscitation: the in-hospital “Utstein” style. Circulation. 1997;95:2213-39.

8. Stewart JA. Determining accurate call-to-shock times is easy. Resuscitation. 2005 Oct;67(1):150-1.

9. In infrequent cases, the code cart and defibrillator may be moved to a deteriorating patient before a full arrest. Such occurrences should be analyzed separately or excluded from analysis.

10. Valenzuela TD et al. Estimating effectiveness of cardiac arrest interventions: a logistic regression survival model. Circulation. 1997;96(10):3308-13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3308.

Benefits of an undocumented defibrillator feature

Benefits of an undocumented defibrillator feature

Research and quality improvement (QI) related to in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation attempts (“codes” from here forward) are hampered significantly by the poor quality of data on time intervals from arrest onset to clinical interventions.1

In 2000, the American Heart Association’s (AHA) Emergency Cardiac Care Guidelines said that current data were inaccurate and that greater accuracy was “the key to future high-quality research”2 – but since then, the general situation has not improved: Time intervals reported by the national AHA-supported registry Get With the Guidelines–Resuscitation (GWTG-R, 200+ hospitals enrolled) include a figure from all hospitals for times to first defibrillation of 1 minute median and 0 minutes first interquartile.3 Such numbers are typical – when they are tracked at all – but they strain credulity, and prima facie evidence is available at most clinical simulation centers simply by timing simulated defibrillation attempts under realistic conditions, as in “mock codes.”4,5

Taking artificially short time-interval data from GWTG-R or other sources at face value can hide serious delays in response to in-hospital arrests. It can also lead to flawed studies and highly questionable conclusions.6

The key to accuracy of critical time intervals – the intervals from arrest to key interventions – is an accurate time of arrest.7 Codes are typically recorded in handwritten form, though they may later be transcribed or scanned into electronic records. The “start” of the code for unmonitored arrests and most monitored arrests is typically taken to be the time that a human bedside recorder, arriving at an unknown interval after the arrest, writes down the first intervention. Researchers acknowledged the problem of artificially short time intervals in 2005, but they did not propose a remedy.1 Since then, the problem of in-hospital resuscitation delays has received little to no attention in the professional literature.

Description of feature

To get better time data from unmonitored resuscitation attempts, it is necessary to use a “surrogate marker” – a stand-in or substitute event – for the time of arrest. This event should occur reliably for each code, and as near as possible to the actual time of arrest. The main early events in a code are starting basic CPR, paging the code, and moving the defibrillator (usually on a code cart) to the scene. Ideally these events occur almost simultaneously, but that is not consistently achieved.

There are significant problems with use of the first two events as surrogate markers: the time of starting CPR cannot be determined accurately, and paging the code is dependent on several intermediate steps that lead to inaccuracy. Furthermore, the times of both markers are recorded using clocks that are typically not synchronized with the clock used for recording the code (defibrillator clock or the human recorder’s timepiece). Reconciliation of these times with the code record, while not particularly difficult,8 is rarely if ever done.

Defibrillator Power On is recorded on the defibrillator timeline and thus does not need to be reconciled with the defibrillator clock, but it is not suitable as a surrogate marker because this time is highly variable: It often does not occur until the time that monitoring pads are placed. Moving the code cart to the scene, which must occur early in the code, is a much more valid surrogate marker, with the added benefit that it can be marked on the defibrillator timeline.

The undocumented feature described here provides that marker. This feature has been a part of the LIFEPAK 20/20e’s design since it was launched in 2002, but it has not been publicized until now and is not documented in the user manual.

Hospital defibrillators are connected to alternating-current (AC) power when not in use. When the defibrillator is moved to the scene of the code, it is obviously necessary to disconnect the defibrillator from the wall outlet, at which time “AC Power Loss” is recorded on the event record generated by the LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators. The defibrillator may be powered on up to 10 minutes later while retaining the AC Power Loss marker in the event record. This surrogate marker for the start time will be on the same timeline as other events recorded by the defibrillator, including times of first monitoring and shocks.

Once the event record is acquired, determining time intervals is accomplished by subtracting clock times (see example, Figure 1).

In the example, using AC Power Loss as the start time, time intervals from arrest to first monitoring (Initial Rhythm on the Event Record) and first shock were 3:12 (07:16:34 minus 07:13:22) and 8:42 (07:22:14 minus 07:13:22). Note that if Power On were used as the surrogate time of arrest in the example, the calculated intervals would be artificially shorter, by 2 min 12 sec.

Using this undocumented feature, any facility using LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators can easily measure critical time intervals during resuscitation attempts with much greater accuracy, including times to first monitoring and first defibrillation. Each defibrillator stores code summaries sufficient for dozens of events and accessing past data is simple. Analysis of the data can provide a much-improved measure of the facility’s speed of response as a baseline for QI.

If desired, the time-interval data thus obtained can also be integrated with the handwritten record. The usual handwritten code sheet records times only in whole minutes, but with one of the more accurate intervals from the defibrillator – to first monitoring or first defibrillation – an adjusted time of arrest can be added to any code record to get other intervals that better approximate real-world response times.9

Research prospects

The feature opens multiple avenues for future research. Acquiring data by this method should be simple for any facility using LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators as its standard devices. Matching the existing handwritten code records with the time intervals obtained using this surrogate time marker will show how inaccurate the commonly reported data are. This can be done with a retrospective study comparing the time intervals from the archived event records with those from the handwritten records, to provide an example of the inaccuracy of data reported in the medical literature. The more accurate picture of time intervals can provide a much-needed yardstick for future research aimed at shortening response times.

The feature can facilitate aggregation of data across multiple facilities that use the LIFEPAK 20/20e as their standard defibrillator. Also, it is possible that other defibrillator manufacturers will duplicate this feature with their devices – it should produce valid data with any defibrillator – although there may be legal and technical obstacles to adopting it.

Combining data from multiple sites might lead to an important contribution to resuscitation research: a reasonably accurate overall survival curve for in-hospital tachyarrhythmic arrests. A commonly cited but crude guideline is that survival from tachyarrhythmic arrests decreases by 10%-15% per minute as defibrillation is delayed,10 but it seems unlikely that the relationship would be linear: Experience and the literature suggest that survival drops very quickly in the first few minutes, flattening out as elapsed time after arrest increases. Aggregating the much more accurate time-interval data from multiple facilities should produce a survival curve for in-hospital tachyarrhythmic arrests that comes much closer to reality.

Conclusion

It is unknown whether this feature will be used to improve the accuracy of reported code response times. It greatly facilitates acquiring more accurate times, but the task has never been especially difficult – particularly when balanced with the importance of better time data for QI and research.8 One possible impediment may be institutional obstacles to publishing studies with accurate response times due to concerns about public relations or legal exposure: The more accurate times will almost certainly be longer than those generally reported.

As was stated almost 2 decades ago and remains true today, acquiring accurate time-interval data is “the key to future high-quality research.”2 It is also key to improving any hospital’s quality of code response. As described in this article, better time data can easily be acquired. It is time for this important problem to be recognized and remedied.

Mr. Stewart has worked as a hospital nurse in Seattle for many years, and has numerous publications to his credit related to resuscitation issues. You can contact him at jastewart325@gmail.com.

References

1. Kaye W et al. When minutes count – the fallacy of accurate time documentation during in-hospital resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005;65(3):285-90.

2. The American Heart Association in collaboration with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, Part 4: the automated external defibrillator: key link in the chain of survival. Circulation. 2000;102(8 Suppl):I-60-76.

3. Chan PS et al. American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 3;358(1):9-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706467.

4. Hunt EA et al. Simulation of in-hospital pediatric medical emergencies and cardiopulmonary arrests: Highlighting the importance of the first 5 minutes. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e34-e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0029.

5. Reeson M et al. Defibrillator design and usability may be impeding timely defibrillation. Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018 Sep;44(9):536-544. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.01.005.

6. Hunt EA et al. American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines – Resuscitation Investigators. Association between time to defibrillation and survival in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest with a first documented shockable rhythm JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182643. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2643.

7. Cummins RO et al. Recommended guidelines for reviewing, reporting, and conducting research on in-hospital resuscitation: the in-hospital “Utstein” style. Circulation. 1997;95:2213-39.

8. Stewart JA. Determining accurate call-to-shock times is easy. Resuscitation. 2005 Oct;67(1):150-1.

9. In infrequent cases, the code cart and defibrillator may be moved to a deteriorating patient before a full arrest. Such occurrences should be analyzed separately or excluded from analysis.

10. Valenzuela TD et al. Estimating effectiveness of cardiac arrest interventions: a logistic regression survival model. Circulation. 1997;96(10):3308-13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3308.

Research and quality improvement (QI) related to in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation attempts (“codes” from here forward) are hampered significantly by the poor quality of data on time intervals from arrest onset to clinical interventions.1

In 2000, the American Heart Association’s (AHA) Emergency Cardiac Care Guidelines said that current data were inaccurate and that greater accuracy was “the key to future high-quality research”2 – but since then, the general situation has not improved: Time intervals reported by the national AHA-supported registry Get With the Guidelines–Resuscitation (GWTG-R, 200+ hospitals enrolled) include a figure from all hospitals for times to first defibrillation of 1 minute median and 0 minutes first interquartile.3 Such numbers are typical – when they are tracked at all – but they strain credulity, and prima facie evidence is available at most clinical simulation centers simply by timing simulated defibrillation attempts under realistic conditions, as in “mock codes.”4,5

Taking artificially short time-interval data from GWTG-R or other sources at face value can hide serious delays in response to in-hospital arrests. It can also lead to flawed studies and highly questionable conclusions.6

The key to accuracy of critical time intervals – the intervals from arrest to key interventions – is an accurate time of arrest.7 Codes are typically recorded in handwritten form, though they may later be transcribed or scanned into electronic records. The “start” of the code for unmonitored arrests and most monitored arrests is typically taken to be the time that a human bedside recorder, arriving at an unknown interval after the arrest, writes down the first intervention. Researchers acknowledged the problem of artificially short time intervals in 2005, but they did not propose a remedy.1 Since then, the problem of in-hospital resuscitation delays has received little to no attention in the professional literature.

Description of feature

To get better time data from unmonitored resuscitation attempts, it is necessary to use a “surrogate marker” – a stand-in or substitute event – for the time of arrest. This event should occur reliably for each code, and as near as possible to the actual time of arrest. The main early events in a code are starting basic CPR, paging the code, and moving the defibrillator (usually on a code cart) to the scene. Ideally these events occur almost simultaneously, but that is not consistently achieved.

There are significant problems with use of the first two events as surrogate markers: the time of starting CPR cannot be determined accurately, and paging the code is dependent on several intermediate steps that lead to inaccuracy. Furthermore, the times of both markers are recorded using clocks that are typically not synchronized with the clock used for recording the code (defibrillator clock or the human recorder’s timepiece). Reconciliation of these times with the code record, while not particularly difficult,8 is rarely if ever done.

Defibrillator Power On is recorded on the defibrillator timeline and thus does not need to be reconciled with the defibrillator clock, but it is not suitable as a surrogate marker because this time is highly variable: It often does not occur until the time that monitoring pads are placed. Moving the code cart to the scene, which must occur early in the code, is a much more valid surrogate marker, with the added benefit that it can be marked on the defibrillator timeline.

The undocumented feature described here provides that marker. This feature has been a part of the LIFEPAK 20/20e’s design since it was launched in 2002, but it has not been publicized until now and is not documented in the user manual.

Hospital defibrillators are connected to alternating-current (AC) power when not in use. When the defibrillator is moved to the scene of the code, it is obviously necessary to disconnect the defibrillator from the wall outlet, at which time “AC Power Loss” is recorded on the event record generated by the LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators. The defibrillator may be powered on up to 10 minutes later while retaining the AC Power Loss marker in the event record. This surrogate marker for the start time will be on the same timeline as other events recorded by the defibrillator, including times of first monitoring and shocks.

Once the event record is acquired, determining time intervals is accomplished by subtracting clock times (see example, Figure 1).

In the example, using AC Power Loss as the start time, time intervals from arrest to first monitoring (Initial Rhythm on the Event Record) and first shock were 3:12 (07:16:34 minus 07:13:22) and 8:42 (07:22:14 minus 07:13:22). Note that if Power On were used as the surrogate time of arrest in the example, the calculated intervals would be artificially shorter, by 2 min 12 sec.

Using this undocumented feature, any facility using LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators can easily measure critical time intervals during resuscitation attempts with much greater accuracy, including times to first monitoring and first defibrillation. Each defibrillator stores code summaries sufficient for dozens of events and accessing past data is simple. Analysis of the data can provide a much-improved measure of the facility’s speed of response as a baseline for QI.

If desired, the time-interval data thus obtained can also be integrated with the handwritten record. The usual handwritten code sheet records times only in whole minutes, but with one of the more accurate intervals from the defibrillator – to first monitoring or first defibrillation – an adjusted time of arrest can be added to any code record to get other intervals that better approximate real-world response times.9

Research prospects

The feature opens multiple avenues for future research. Acquiring data by this method should be simple for any facility using LIFEPAK 20/20e defibrillators as its standard devices. Matching the existing handwritten code records with the time intervals obtained using this surrogate time marker will show how inaccurate the commonly reported data are. This can be done with a retrospective study comparing the time intervals from the archived event records with those from the handwritten records, to provide an example of the inaccuracy of data reported in the medical literature. The more accurate picture of time intervals can provide a much-needed yardstick for future research aimed at shortening response times.

The feature can facilitate aggregation of data across multiple facilities that use the LIFEPAK 20/20e as their standard defibrillator. Also, it is possible that other defibrillator manufacturers will duplicate this feature with their devices – it should produce valid data with any defibrillator – although there may be legal and technical obstacles to adopting it.

Combining data from multiple sites might lead to an important contribution to resuscitation research: a reasonably accurate overall survival curve for in-hospital tachyarrhythmic arrests. A commonly cited but crude guideline is that survival from tachyarrhythmic arrests decreases by 10%-15% per minute as defibrillation is delayed,10 but it seems unlikely that the relationship would be linear: Experience and the literature suggest that survival drops very quickly in the first few minutes, flattening out as elapsed time after arrest increases. Aggregating the much more accurate time-interval data from multiple facilities should produce a survival curve for in-hospital tachyarrhythmic arrests that comes much closer to reality.

Conclusion

It is unknown whether this feature will be used to improve the accuracy of reported code response times. It greatly facilitates acquiring more accurate times, but the task has never been especially difficult – particularly when balanced with the importance of better time data for QI and research.8 One possible impediment may be institutional obstacles to publishing studies with accurate response times due to concerns about public relations or legal exposure: The more accurate times will almost certainly be longer than those generally reported.

As was stated almost 2 decades ago and remains true today, acquiring accurate time-interval data is “the key to future high-quality research.”2 It is also key to improving any hospital’s quality of code response. As described in this article, better time data can easily be acquired. It is time for this important problem to be recognized and remedied.

Mr. Stewart has worked as a hospital nurse in Seattle for many years, and has numerous publications to his credit related to resuscitation issues. You can contact him at jastewart325@gmail.com.

References

1. Kaye W et al. When minutes count – the fallacy of accurate time documentation during in-hospital resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005;65(3):285-90.

2. The American Heart Association in collaboration with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, Part 4: the automated external defibrillator: key link in the chain of survival. Circulation. 2000;102(8 Suppl):I-60-76.

3. Chan PS et al. American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 3;358(1):9-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706467.

4. Hunt EA et al. Simulation of in-hospital pediatric medical emergencies and cardiopulmonary arrests: Highlighting the importance of the first 5 minutes. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e34-e43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0029.

5. Reeson M et al. Defibrillator design and usability may be impeding timely defibrillation. Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018 Sep;44(9):536-544. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.01.005.

6. Hunt EA et al. American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines – Resuscitation Investigators. Association between time to defibrillation and survival in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest with a first documented shockable rhythm JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182643. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2643.

7. Cummins RO et al. Recommended guidelines for reviewing, reporting, and conducting research on in-hospital resuscitation: the in-hospital “Utstein” style. Circulation. 1997;95:2213-39.

8. Stewart JA. Determining accurate call-to-shock times is easy. Resuscitation. 2005 Oct;67(1):150-1.

9. In infrequent cases, the code cart and defibrillator may be moved to a deteriorating patient before a full arrest. Such occurrences should be analyzed separately or excluded from analysis.

10. Valenzuela TD et al. Estimating effectiveness of cardiac arrest interventions: a logistic regression survival model. Circulation. 1997;96(10):3308-13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3308.

Letter to the Editor/

The study by Davis et al.[1] corroborates another recent study on deferred defibrillation in hospitals, which also showed poorer survival with the current American Heart Association/International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation deferred defibrillation guideline.[2] The guideline itself resulted not from consideration of the 3‐phase model as the authors appear to suggest, but rather from belated recognition that the long hands‐off periods required by automated external defibrillators (AEDs) for rhythm analysis significantly decrease shock success and survival. However, the guideline was also applied to manual defibrillation, with no discernable rationale.[3]

The poor results from deferred defibrillation in hospitals may be largely due to the fact that the great majority of defibrillations in that setting are manual. Deferring defibrillation to mitigate hands‐off time is completely inappropriate with manual defibrillation; with a manual device, a shock can be delivered in less than 5 seconds if done correctly.

The present study supports the view that deferred defibrillation is ill advised and harmful with manual devices, particularly in hospitals. Distorting the guideline to cover manual devices has served to paper over a major shortcoming of AEDs vis‐a‐vis manual defibrillators and has likely caused unnecessary deaths. The guideline should be changed.

- , , , , . A focused investigation of expedited, stack of three shocks versus chest compressions first followed by single shocks for monitored ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia cardiopulmonary arrest in an in‐hospital setting. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(4):264–268.

- , , , et al. Defibrillation time intervals and outcomes of cardiac arrest in hospital: retrospective cohort study from Get With The Guidelines‐Resuscitation registry. BMJ. 2016;353:i1653.

- 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care part 5: electrical therapies. Circulation. 2005;112:IV‐35–IV‐46.

The study by Davis et al.[1] corroborates another recent study on deferred defibrillation in hospitals, which also showed poorer survival with the current American Heart Association/International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation deferred defibrillation guideline.[2] The guideline itself resulted not from consideration of the 3‐phase model as the authors appear to suggest, but rather from belated recognition that the long hands‐off periods required by automated external defibrillators (AEDs) for rhythm analysis significantly decrease shock success and survival. However, the guideline was also applied to manual defibrillation, with no discernable rationale.[3]

The poor results from deferred defibrillation in hospitals may be largely due to the fact that the great majority of defibrillations in that setting are manual. Deferring defibrillation to mitigate hands‐off time is completely inappropriate with manual defibrillation; with a manual device, a shock can be delivered in less than 5 seconds if done correctly.

The present study supports the view that deferred defibrillation is ill advised and harmful with manual devices, particularly in hospitals. Distorting the guideline to cover manual devices has served to paper over a major shortcoming of AEDs vis‐a‐vis manual defibrillators and has likely caused unnecessary deaths. The guideline should be changed.

The study by Davis et al.[1] corroborates another recent study on deferred defibrillation in hospitals, which also showed poorer survival with the current American Heart Association/International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation deferred defibrillation guideline.[2] The guideline itself resulted not from consideration of the 3‐phase model as the authors appear to suggest, but rather from belated recognition that the long hands‐off periods required by automated external defibrillators (AEDs) for rhythm analysis significantly decrease shock success and survival. However, the guideline was also applied to manual defibrillation, with no discernable rationale.[3]

The poor results from deferred defibrillation in hospitals may be largely due to the fact that the great majority of defibrillations in that setting are manual. Deferring defibrillation to mitigate hands‐off time is completely inappropriate with manual defibrillation; with a manual device, a shock can be delivered in less than 5 seconds if done correctly.

The present study supports the view that deferred defibrillation is ill advised and harmful with manual devices, particularly in hospitals. Distorting the guideline to cover manual devices has served to paper over a major shortcoming of AEDs vis‐a‐vis manual defibrillators and has likely caused unnecessary deaths. The guideline should be changed.

- , , , , . A focused investigation of expedited, stack of three shocks versus chest compressions first followed by single shocks for monitored ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia cardiopulmonary arrest in an in‐hospital setting. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(4):264–268.

- , , , et al. Defibrillation time intervals and outcomes of cardiac arrest in hospital: retrospective cohort study from Get With The Guidelines‐Resuscitation registry. BMJ. 2016;353:i1653.

- 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care part 5: electrical therapies. Circulation. 2005;112:IV‐35–IV‐46.

- , , , , . A focused investigation of expedited, stack of three shocks versus chest compressions first followed by single shocks for monitored ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia cardiopulmonary arrest in an in‐hospital setting. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(4):264–268.

- , , , et al. Defibrillation time intervals and outcomes of cardiac arrest in hospital: retrospective cohort study from Get With The Guidelines‐Resuscitation registry. BMJ. 2016;353:i1653.

- 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care part 5: electrical therapies. Circulation. 2005;112:IV‐35–IV‐46.