User login

When are Oral Antibiotics a Safe and Effective Choice for Bacterial Bloodstream Infections? An Evidence-Based Narrative Review

Bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Approximately 600,000 BSI cases occur annually, resulting in 85,000 deaths,1 at a cost exceeding $1 billion.2 Traditionally, BSIs have been managed with intravenous antimicrobials, which rapidly achieve therapeutic blood concentrations, and are viewed as more potent than oral alternatives. Indeed, for acutely ill patients with bacteremia and sepsis, timely intravenous antimicrobials are lifesaving.3

However, whether intravenous antimicrobials are essential for the entire treatment course in BSIs, particularly for uncomplicated episodes, is controversial. Patients that are clinically stable or have been stabilized after an initial septic presentation may be appropriate candidates for treatment with oral antimicrobials. There are costs and risks associated with extended courses of intravenous agents, such as the necessity for long-term intravenous catheters, which entail risks for procedural complications, secondary infections, and thrombosis. A prospective study of 192 peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) episodes reported an overall complication rate of 30.2%, including central line-associated BSIs (CLABSI) or venous thrombosis.4 Other studies also identified high rates of thrombosis5 and PICC-related CLABSI, particularly in patients with malignancy, where sepsis-related complications approach 25%.6 Additionally, appropriate care of indwelling catheters requires significant financial and healthcare resources.

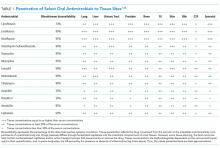

Oral antimicrobial therapy for bacterial BSIs offers several potential benefits. Direct economic and healthcare workforce savings are expected to be significant, and procedural and catheter-related complications would be eliminated.7 Moreover, oral therapy provides antimicrobial stewardship by reducing the use of broad-spectrum intravenous agents.8 Recent infectious disease “Choosing Wisely” initiatives recommend clinicians “prefer oral formulations of highly bioavailable antimicrobials whenever possible”,9 and this approach is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention antibiotic stewardship program.10 However, the expected savings and benefits of oral therapy would be lost should they be less effective and result in treatment failure or relapse of the primary BSI. Pathogen susceptibility, gastrointestinal absorption, oral bioavailability, patient tolerability, and adherence with therapy need to be carefully considered before choosing oral antimicrobials. Thus, oral antimicrobial therapy for BSI should be utilized in carefully selected circumstances.

In this narrative review, we highlight areas where oral therapy is safe and effective in treating bloodstream infections, as well as offer guidance to clinicians managing patients experiencing BSI. Given the lack of robust clinical trials on this subject, the evidence for performing a systematic review was insufficient. Thus, the articles and recommendations cited in this review were selected based on the authors’ experiences to represent the best available evidence.

Infection Source Control

Pathogen and Antimicrobial Factors

Patient Factors

Evidence Regarding Bloodstream Infections due to Gram-Negative Rods

BSIs due to gram-negative rods (GNRs) are common and cause significant morbidity and mortality. GNRs represent a broad and diverse array of pathogens. We focus on the Enterobacteriaceae family and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, because they are frequently encountered in clinical practice.1

Gram-Negative Rods, Enterobacteriaceae Family

The Enterobacteriaceae family includes Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Proteus, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Citrobacter species. The range of illnesses caused by Enterobacteriaceae is as diverse as the family, encompassing most body sites. Although most Enterobacteriaceae are intrinsically susceptible to antibiotics, there is potential for significant multi-drug resistance. Of particular recent concern has been the emergence of Enterobacteriaceae that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and even carbapenem-resistant strains.14

However, Enterobacteriaceae species susceptible to oral antimicrobials are often suitable candidates for oral BSI therapy. Among 106 patients with GNR BSI treated with a highly bioavailable oral antibiotic (eg, levofloxacin), the treatment failure rate was only 2% (versus 14% when an antimicrobial with only moderate or low bioavailability was selected).15 Oral treatment of Enterobacteriaceae BSIs secondary to urinary tract infection has been best studied. A prospective randomized, controlled trial evaluated oral versus intravenous ciprofloxacin amongst 141 patients with severe pyelonephritis or complicated urinary tract infections, in which the rate of bacteremia was 38%.16 Notably, patients with obstruction or renal abscess were excluded from the trial. No significant differences in microbiological failure or unsatisfactory clinical responses were found between the IV and oral treatment groups. Additionally, a Cochrane review reported that oral antibiotic therapy is no less effective than intravenous therapy for severe UTI, although data on BSI frequency were not provided.17

Resistance to fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin has been identified as a risk factor for GNR BSI oral treatment failure, highlighting the importance of confirming susceptibilities before committing to an oral treatment plan.18,19 Even ESBL Enterobacteriaceae can be considered for treatment with fluoroquinolones if susceptibilities allow.20

The ideal duration of therapy for GNR BSI is an area of active research. A recent retrospective trial showed no difference in all-cause mortality or recurrent BSI in GNR BSI treated for 8 versus 15 days.21 A recent meta-analysis suggested that 7 days of therapy was noninferior to a longer duration therapy (10–14 days) for pyelonephritis, in which a subset was bacteremic.22 However, another trial reported that short course therapy for GNR BSI (<7 days) is associated with higher risk of treatment failure.22 Further data are needed.

Gram-Negative Rods, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common pathogen, intrinsically resistant to many antimicrobials, and readily develops antimicrobial resistance during therapy. Fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and delafloxacin) are the only currently available oral agents with antipseudomonal activity. However, fluoroquinolones may not achieve blood concentrations appropriate for P. aeruginosa treatment at standard doses, while higher dose regimens may be associated with increased risk for undesirable side effects.24,25 Currently, given the minimal trial data comparing oral versus intravenous therapy for P. aeruginosa BSIs, and multiple studies indicating increased mortality when P. aeruginosa is treated inappropriately,26,27 we prefer a conservative approach and consider oral therapy a less-preferred option.

Evidence Regarding Bloodstream Infections due to Gram-Positive Cocci

The majority of bloodstream infections in the United States, and the resultant morbidity and mortality, are from gram-positive cocci (GPCs) such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus species.1

Gram-Positive Cocci, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Of the approximately 900,000 annual cases of S. pneumoniae infection in the United States, approximately 40,000 are complicated by BSI, with 70% of those cases being secondary to pneumococcal pneumonia.28 In studies on patients with pneumococcal pneumonia, bacteremic cases generally fare worse than those without bacteremia.29,30 However, several trials demonstrated comparable outcomes in the setting of bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia when switched early (within 3 days) from intravenous to oral antibiotics to complete a 7-day course.31,32 Before pneumococcal penicillin resistance became widespread, oral penicillin was shown to be effective, and remains an option for susceptible strains.33 It is worth noting, however, that other trials have shown a mortality benefit from treating bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia initially with dual-therapy including a β-lactam and macrolide such as azithromycin. This observation highlights the importance of knowing the final susceptibility data prior to consolidating to monotherapy with an oral agent, and that macrolides may have beneficial anti-inflammatory effects, though further research is needed.34,35

Although the evidence for treating bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia using a highly active and absorbable oral agent is fairly robust, S. pneumoniae BSI secondary to other sites of infection sites is less well studied and may require a more conservative approach.

Gram-Positive Cocci, β-hemolytic Streptococcus species

β-Hemolytic Streptococci include groups A to H, of which groups A (S. pyogenes) and B (S. agalactiae) are the most commonly implicated in BSIs.36 Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is classically associated with streptococcal pharyngitis and Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is associated with postpartum endometritis and neonatal meningitis, though both are virulent organisms with a potential to cause invasive infection throughout the body and in all age-groups. Up to 14% of GAS and 41% GBS BSIs have no clear source;37,38 given these are skin pathogens, such scenarios likely represent invasion via microabrasion. As β-hemolytic streptococcal BSI is often observed in the context of necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections, surgical source control is particularly important.39 GAS remains exquisitely susceptible to penicillin, and intravenous penicillin remains the mainstay for invasive disease; GBS has higher penicillin resistance rates than GAS.40 Clindamycin should be added when there is concern for severe disease or toxic shock.41 Unfortunately, oral penicillin is poorly bioavailable (approximately 50%), and there has been recent concern regarding inducible clindamycin resistance in GAS.42 Thus, oral penicillin V and/or clindamycin is a potentially risky strategy, with no clinical trials supporting this approach; however, they may be reasonable options in selected patients with source control and stable hemodynamics. Amoxicillin has high bioavailability (85%) and may be effective; however, there is lack of supporting data. Highly bioavailable agents such as levofloxacin and linezolid have GAS and GBS activity43 and might be expected to produce satisfactory outcomes. Because no clinical trials have compared these agents with intravenous therapy for BSI, caution is advised. Although bacteriostatic against Staphylococcus, linezolid is bactericidal against Streptococcus.44 Fluoroquinolone resistance amongst β-hemolytic Streptococcus is rare (approximately 0.5%) but does occur.45

Gram-Positive Cocci, Staphylococcus Species

Staphylococcus species include S. aureus (including methicillin susceptible and resistant strains: MSSA and MRSA, respectively) and coagulase-negative species, which include organisms such as S. epidermidis. S. aureus is the most common cause of BSI mortality in the United States,1 with mortality rates estimated at 20%–40% per episode.46 Infectious disease consultation has been associated with decreased mortality and is recommended.47 The guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of MRSA recommend the use of parenteral agents for BSI.48 It is important to consider if a patient with S. aureus BSI has infective endocarditis.

Oral antibiotic therapy for S. aureus BSI is not currently standard practice. Although trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) has favorable pharmacokinetics and case series of using it successfully for BSI exist,49 TMP-SMX showed inferior outcomes in a randomized trial comparing oral TMP-SMX with intravenous vancomycin in a series of 101 S. aureus infections.50 This observation has been replicated.51 Data on doxycycline or clindamycin for S. aureus BSI are limited, and IDSA guidelines advise against their use in this setting because they are predominantly bacteriostatic.48 Linezolid has favorable pharmacokinetics, with approximately 100% bioavailability, and S. aureus resistance to linezolid is rare.52 Several randomized trials have compared oral linezolid with intravenous vancomycin for S. aureus BSI; for instance, Stevens et al. randomized 460 patients with S. aureus infection (of whom 18% had BSI) to linezolid versus vancomycin and observed similar clinical cure rates.53 A pooled analysis showed oral linezolid was noninferior to vancomycin specifically for S. aureus BSI.54 However, long-term use is often limited by hematologic toxicity, peripheral or optic neuropathy (which can be permanent), and induced serotonin syndrome. Additionally, linezolid is bacteriostatic, not bactericidal against S. aureus. Using oral linezolid as a first-line option for S. aureus BSI would not be recommended; however, it may be used as a second-line treatment option in selected cases. Tedizolid has similar pharmacokinetics and spectrum of activity with fewer side effects; however, clinical data on its use for S. aureus BSI are lacking.55 Fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin and the newer agent delafloxacin have activity against S. aureus, including MRSA, but on-treatment emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance is a concern, and data on delafloxacin for BSI are lacking.56,57 Older literature suggested the combination of ciprofloxacin and rifampin was effective against right-sided S. aureus endocarditis,58 and other oral fluoroquinolone-rifamycin combinations have also been found to be effective59 However, this approach is currently not a standard therapy, nor is it widely used. Decisions on the duration of therapy for S. aureus BSI should be made in conjunction with an infectious diseases specialist; 14 days is currently regarded as a minimum.47,48

Published data regarding oral treatment of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) BSI are limited. Most CoNS bacteremia and up to 80% Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteremia represent blood culture contamination, though true infection from CoNS is not uncommon, particularly in patients with indwelling catheters.60 An exception is the CoNS species Staphylococcus lugdunensis, which is more virulent, and bacteremia with this organism usually warrants antibiotics. Oral antimicrobial therapy is currently not a standard treatment practice for CoNS BSI that is felt to represent true infection; however, linezolid has been successfully used in case series.61

Gram-Positive Cocci, Enterococcus

E. faecium and E. faecalis are commonly implicated in BSI.1 Similar to S. aureus, infective endocarditis must be ruled out when treating enterococcus BSI; a scoring system has been proposed to assist in deciding if such patients require echocardiography.62 Intravenous ampicillin is a preferred, highly effective agent for enterococci treatment when the organism is susceptible.44 However, oral ampicillin has poor bioavailability (50%), and data for its use in BSI are lacking. For susceptible strains, amoxicillin has comparable efficacy for enterococci and enhanced bioavailability (85%); high dose oral amoxicillin could be considered, but there is minimal clinical trial data to support this approach. Fluoroquinolones exhibit only modest activity against enterococci and would be an inferior choice for BSI.63 Although often sensitive to oral tetracyclines, data on their use in enterococcal BSI are insufficient. Nitrofurantoin can be used for susceptible enterococcal urinary tract infection; however, it does not achieve high blood concentrations and should not be used for BSI.

There is significant data comparing oral linezolid with intravenous daptomycin for vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) BSI. In a systematic review including 10 trials using 30-day all-cause mortality as the primary outcome, patients treated with daptomycin demonstrated higher odds of death (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.08–2.40) compared with those treated with linezolid.64 However, more recent data suggested that higher daptomycin doses than those used in these earlier trials resulted in improved VRE BSI outcomes.65 A subsequent study reported that VRE BSI treatment with linezolid is associated with significantly higher treatment failure and mortality compared with daptomycin therapy.66 Further research is needed, but should the side-effect profile of linezolid be tolerable, it remains an effective option for oral treatment of enterococcal BSIs.

Evidence Regarding Anaerobic Bacterial Blood Stream Infection

Anaerobic bacteria include Bacteroides, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Veillonella, and Clostridium. Anaerobes account for approximately 4% of bacterial BSIs, and are often seen in the context of polymicrobial infection.67 Given that anaerobes are difficult to recover, and that antimicrobial resistance testing is more labor intensive, antibiotic therapy choices are often made empirically.67 Unfortunately, antibiotic resistance amongst anaerobes is increasing.68 However, metronidazole remains highly active against a majority of anaerobes, with only a handful of treatment failures reported,69 and has a highly favorable pharmacokinetic profile for oral treatment. Oral metronidazole remains an effective choice for many anaerobic BSIs. Considering the polymicrobial nature of many anaerobic infections, source control is important, and concomitant GNR infection must be ruled out before using metronidazole monotherapy.

Clindamycin has significant anaerobic activity, but Bacteroides resistance has increased significantly in recent years, as high as 26%-44%.70 Amoxicillin-clavulanate has good anaerobic coverage, but bioavailability of clavulanate is limited (50%), making it inferior for BSI. Bioavailability is also limited for cephalosporins with anaerobic activity, such as cefuroxime. Moxifloxacin is a fluoroquinolone with some anaerobic coverage and a good oral pharmacokinetic profile, but Bacteroides resistance can be as high as 50%, making it a risky empiric choice.68

Conclusions

Bacterial BSIs are common and result in significant morbidity and mortality, with high associated healthcare costs. Although BSIs are traditionally treated with intravenous antimicrobials, many BSIs can be safely and effectively cured using oral antibiotics. When appropriately selected, oral antibiotics offer lower costs, fewer side effects, promote antimicrobial stewardship, and are easier for patients. Ultimately, the decision to use oral versus intravenous antibiotics must consider the characteristics of the pathogen, patient, and drug.

Disclosures

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

1. Goto M, Al-Hasan MN. Overall burden of bloodstream infection and nosocomial bloodstream infection in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(6):501-509. PubMed

2. Kilgore M, Brossette S. Cost of bloodstream infections. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(10):S172.e1-3. PubMed

3. Youkee D, Hulme W, Roberts T, Daniels R, Nutbeam T, Keep J. Time Matters: Antibiotic Timing in Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(10):e1016-1017. PubMed

4. Grau D, Clarivet B, Lotthé A, Bommart S, Parer S. Complications with peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) used in hospitalized patients and outpatients: a prospective cohort study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;28;6:18. PubMed

5. Allen AW, Megargell JL, Brown DB, Lynch FC, Singh H, Singh Y, Waybill PN. Venous Thrombosis Associated with the Placement of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(10):1309-1314. PubMed

6. Cheong K, Perry D, Karapetis C, Koczwara B. High rate of complications associated with peripherally inserted central venous catheters in patients with solid tumours. Intern Med J. 2004;34(5):234-238. PubMed

7. Cunha BA. Oral antibiotic therapy of serious systemic infections. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(6):1197-1222. PubMed

8. Cyriac JM, James E. Switch over from intravenous to oral therapy: A concise overview. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2014;5(2):83-87. PubMed

9. Lehmann C, Berner R, Bogner JR, et al. The “Choosing Wisely” initiative in infectious diseases. Infection. 2017;45(3):263-268. PubMed

10. Lehmann C, Berner R, Bogner JR, et al. The “Choosing Wisely” initiative in infectious diseases. Infection. 2017;45(3):263-268. PubMed

11. Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1-45. PubMed

12. Spellberg B, Lipsky BA. Systemic antibiotic therapy for chronic osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(3):393-407. PubMed

13. Cua YM, Kripalani S. Medication Use in the Transition from Hospital to Home. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(2):136. PubMed

14. Paterson DL. Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria: Enterobacteriaceae. Am J Med. 2006; 119(6):S20-28.

15. Kutob LF, Justo JA, Bookstaver PB, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Effectiveness of oral antibiotics for definitive therapy of Gram-negative bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(5):498-503. PubMed

16. Mombelli G, Pezzoli R, Pinoja-Lutz G, Monotti R, Marone C, Franciolli M Oral vs Intravenous Ciprofloxacin in the Initial Empirical Management of Severe Pyelonephritis or Complicated Urinary Tract Infections: A Prospective Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(1):53-58. PubMed

17. Pohl A. Modes of administration of antibiotics for symptomatic severe urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003237. PubMed

18. Brigmon MM, Bookstaver PB, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Impact of fluoroquinolone resistance in Gram-negative bloodstream infections on healthcare utilization. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(9):843-849. PubMed

19. Ortega M, Marco F, Soriano A, et al. Analysis of 4758 Escherichia coli bacteraemia episodes: predictive factors for isolation of an antibiotic-resistant strain and their impact on the outcome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(3):568-574. PubMed

20. Lo CL, Lee CC, Li CW, et al. Fluoroquinolone therapy for bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2017;50(3):355-361. PubMed

21. Chotiprasitsakul D, Han JH, Cosgrove SE, et al. Comparing the Outcomes of Adults With Enterobacteriaceae Bacteremia Receiving Short-Course Versus Prolonged-Course Antibiotic Therapy in a Multicenter, Propensity Score–Matched Cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2017; cix767. doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix767 PubMed

22. Eliakim-Raz N, Yahav D, Paul M, Leibovici L. Duration of antibiotic treatment for acute pyelonephritis and septic urinary tract infection-- 7 days or less versus longer treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(10):2183-2191. PubMed

23. Nelson AN, Justo JA, Bookstaver PB, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated Gram-negative bloodstream infections. Infection. 2017;45(5):613-620. PubMed

24. Zelenitsky S, Ariano R, Harding G, Forrest A. Evaluating Ciprofloxacin Dosing for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection by Using Clinical Outcome-Based Monte Carlo Simulations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(10):4009-4014. PubMed

25. Cazaubon Y, Bourguignon L, Goutelle S, Martin O, Maire P, Ducher M. Are ciprofloxacin dosage regimens adequate for antimicrobial efficacy and prevention of resistance? Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection in elderly patients as a simulation case study. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2015;29(6):615-624. PubMed

26. Micek ST, Lloyd AE, Ritchie DJ, Reichley RM, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bloodstream Infection: Importance of Appropriate Initial Antimicrobial Treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(4):1306-1311. PubMed

27. Chamot E, Boffi El Amari E, Rohner P, Van Delden C. Effectiveness of Combination Antimicrobial Therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(9):2756-2764. PubMed

28. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) Emerging Infections Program Network Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/spneu13.pdf. Published November, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2017.

29. Brandenburg JA, Marrie TJ, Coley CM, et al. Clinical presentation, processes and outcomes of care for patients with pneumococcal pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(9):638-646. PubMed

30. Musher DM, Alexandraki I, Graviss EA, et al. Bacteremic and nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. A prospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79(4):210-221. PubMed

31. Ramirez JA, Bordon J. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with bacteremic community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161(6):848-850. PubMed

32. Oosterheert JJ, Bonten MJM, Schneider MME, et al. Effectiveness of early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in severe community acquired pneumonia: multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;333(7580):1193. PubMed

33. Austrian R, Winston AL. The efficacy of penicillin V (phenoxymethyl-penicillin) in the treatment of mild and of moderately severe pneumococcal pneumonia. Am J Med Sci. 1956;232(6):624-628. PubMed

34. Waterer GW, Somes GW, Wunderink RG. Monotherapy May Be Suboptimal for Severe Bacteremic Pneumococcal Pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161(15):1837-1842. PubMed

35. Baddour LM, Yu VL, Klugman KP, et al. International Pneumococcal Study Group. Combination antibiotic therapy lowers mortality among severely ill patients with pneumococcal bacteremia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):440-444. PubMed

36. Sylvetsky N, Raveh D, Schlesinger Y, Rudensky B, Yinnon AM. Bacteremia due to beta-hemolytic streptococcus group g: increasing incidence and clinical characteristics of patients. Am J Med. 2002;112(8):622-626. PubMed

37. Davies HD, McGeer A, Schwartz B, Green, et al; Ontario Group A Streptococcal Study Group. Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(8):547-554. PubMed

38. Farley MM, Harvey C, Stull T, et al. A Population-Based Assessment of Invasive Disease Due to Group B Streptococcus in Nonpregnant Adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(25):1807-1811. PubMed

39. Nelson GE, Pondo T, Toews KA, et al. Epidemiology of Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in the United States, 2005-2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):478-486. PubMed

40. Betriu C, Gomez M, Sanchez A, Cruceyra A, Romero J, Picazo JJ. Antibiotic resistance and penicillin tolerance in clinical isolates of group B streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38(9):2183-2186. PubMed

41. Zimbelman J, Palmer A, Todd J. Improved outcome of clindamycin compared with beta-lactam antibiotic treatment for invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(12):1096-1100. PubMed

42. Chen I, Kaufisi P, Erdem G. Emergence of erythromycin- and clindamycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes emm 90 strains in Hawaii. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(1):439-441. PubMed

43. Biedenbach DJ, Jones RN. The comparative antimicrobial activity of levofloxacin tested against 350 clinical isolates of streptococci. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;25(1):47–51. PubMed

44. Gilbert DN, Chambers HF, Eliopoulos GM, Saag MS, Pavia AT. Sanford Guide To Antimicrobial Therapy 2017. Dallas, TX. Antimicrobial Theapy, Inc, 2017.

45. Biedenbach DJ, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Jones RN. Characterization of fluoroquinolone-resistant beta-hemolytic Streptococcus spp. isolated in North America and Europe including the first report of fluoroquinolone-resistant Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997-2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;55(2):119-127. PubMed

46. Shurland S, Zhan M, Bradham DD, Roghmann M-C. Comparison of mortality risk associated with bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(3):2739. PubMed

47. Forsblom E, Ruotsalainen E, Ollgren J, Järvinen A. Telephone consultation cannot replace bedside infectious disease consultation in the management of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(4):527-535. PubMed

48. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):e18-55. PubMed

49. Adra M, Lawrence KR. Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole for Treatment of Severe Staphylococcus aureus Infections. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(2):338-341. PubMed

50. Markowitz N, Quinn EL, Saravolatz LD. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole compared with vancomycin for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infection. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(5):390-398. PubMed

51. Paul M, Bishara J, Yahav D, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus vancomycin for severe infections caused by meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;350:h2219. PubMed

52. Sánchez García M, De la Torre MA, Morales G, et al. Clinical outbreak of linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an intensive care unit. JAMA. 2010;303(22):2260-2264. PubMed

53. Stevens DL, Herr D, Lampiris H, Hunt JL, Batts DH, Hafkin B. Linezolid versus vancomycin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(11):1481-1490. PubMed

54. Shorr AF, Kunkel MJ, Kollef M. Linezolid versus vancomycin for Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: pooled analysis of randomized studies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(5):923-929. PubMed

55. Kisgen JJ, Mansour H, Unger NR, Childs LM. Tedizolid: a new oxazolidinone antimicrobial. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2014;71(8):621-633. PubMed

56. Gade ND, Qazi MS. Fluoroquinolone Therapy in Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Where Do We Stand? J Lab Physicians. 2013;5(2):109-112. PubMed

57. Kingsley J, Mehra P, Lawrence LE, et al. A randomized, double-blind, Phase 2 study to evaluate subjective and objective outcomes in patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections treated with delafloxacin, linezolid or vancomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(3):821-829. PubMed

58. Dworkin RJ, Lee BL, Sande MA, Chambers HF. Treatment of right-sided Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in intravenous drug users with ciprofloxacin and rifampicin. Lancet. 1989;2(8671):1071-1073. PubMed

59. Schrenzel J, Harbarth S, Schockmel G, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial to Compare Fleroxacin-Rifampicin with Flucloxacillin or Vancomycin for the Treatment of Staphylococcal Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(9):1285-1292. PubMed

60. Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(4):788-802. PubMed

61. Antony SJ, Diaz-Vasquez E, Stratton C. Clinical experience with linezolid in the treatment of resistant gram-positive infections. J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93(10):386-391. PubMed

62. Bouza E, Kestler M, Beca T, et al. The NOVA score: a proposal to reduce the need for transesophageal echocardiography in patients with enterococcal bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(4):528-535. PubMed

63. Martínez-Martínez L, Joyanes P, Pascual A, Terrero E, Perea EJ. Activity of eight fluoroquinolones against enterococci. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3(4):497-499. PubMed

64. Balli EP, Venetis CA, Miyakis S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Linezolid versus Daptomycin for Treatment of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(2):734-739. PubMed

70. Snydman DR, Jacobus NV, McDermott LA, et al. National survey on the susceptibility of Bacteroides fragilis group: report and analysis of trends in the United States from 1997 to 2004. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(5):1649-1655. PubMed

69. Snydman DR, Jacobus NV, McDermott LA, et al. Lessons learned from the anaerobe survey: historical perspective and review of the most recent data (2005-2007). Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50 Suppl 1:S26-33. PubMed

68. Karlowsky JA, Walkty AJ, Adam HJ, Baxter MR, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Bacteroides fragilis group in Canada in 2010-2011: CANWARD surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(3):1247-1252. PubMed

67. Salonen JH, Eerola E, Meurman O. Clinical significance and outcome of anaerobic bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(6):1413-1417. PubMed

66. Britt NS, Potter EM, Patel N, Steed ME. Comparison of the Effectiveness and Safety of Linezolid and Daptomycin in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Bloodstream Infection: A National Cohort Study of Veterans Affairs Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(6):871-878. PubMed

65. Chuang YC, Lin HY, Chen PY, et al. Effect of Daptomycin Dose on the Outcome of Vancomycin-Resistant, Daptomycin-Susceptible Enterococcus faecium Bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(8):1026-1034. PubMed

Bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Approximately 600,000 BSI cases occur annually, resulting in 85,000 deaths,1 at a cost exceeding $1 billion.2 Traditionally, BSIs have been managed with intravenous antimicrobials, which rapidly achieve therapeutic blood concentrations, and are viewed as more potent than oral alternatives. Indeed, for acutely ill patients with bacteremia and sepsis, timely intravenous antimicrobials are lifesaving.3

However, whether intravenous antimicrobials are essential for the entire treatment course in BSIs, particularly for uncomplicated episodes, is controversial. Patients that are clinically stable or have been stabilized after an initial septic presentation may be appropriate candidates for treatment with oral antimicrobials. There are costs and risks associated with extended courses of intravenous agents, such as the necessity for long-term intravenous catheters, which entail risks for procedural complications, secondary infections, and thrombosis. A prospective study of 192 peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) episodes reported an overall complication rate of 30.2%, including central line-associated BSIs (CLABSI) or venous thrombosis.4 Other studies also identified high rates of thrombosis5 and PICC-related CLABSI, particularly in patients with malignancy, where sepsis-related complications approach 25%.6 Additionally, appropriate care of indwelling catheters requires significant financial and healthcare resources.

Oral antimicrobial therapy for bacterial BSIs offers several potential benefits. Direct economic and healthcare workforce savings are expected to be significant, and procedural and catheter-related complications would be eliminated.7 Moreover, oral therapy provides antimicrobial stewardship by reducing the use of broad-spectrum intravenous agents.8 Recent infectious disease “Choosing Wisely” initiatives recommend clinicians “prefer oral formulations of highly bioavailable antimicrobials whenever possible”,9 and this approach is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention antibiotic stewardship program.10 However, the expected savings and benefits of oral therapy would be lost should they be less effective and result in treatment failure or relapse of the primary BSI. Pathogen susceptibility, gastrointestinal absorption, oral bioavailability, patient tolerability, and adherence with therapy need to be carefully considered before choosing oral antimicrobials. Thus, oral antimicrobial therapy for BSI should be utilized in carefully selected circumstances.

In this narrative review, we highlight areas where oral therapy is safe and effective in treating bloodstream infections, as well as offer guidance to clinicians managing patients experiencing BSI. Given the lack of robust clinical trials on this subject, the evidence for performing a systematic review was insufficient. Thus, the articles and recommendations cited in this review were selected based on the authors’ experiences to represent the best available evidence.

Infection Source Control

Pathogen and Antimicrobial Factors

Patient Factors

Evidence Regarding Bloodstream Infections due to Gram-Negative Rods

BSIs due to gram-negative rods (GNRs) are common and cause significant morbidity and mortality. GNRs represent a broad and diverse array of pathogens. We focus on the Enterobacteriaceae family and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, because they are frequently encountered in clinical practice.1

Gram-Negative Rods, Enterobacteriaceae Family

The Enterobacteriaceae family includes Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Proteus, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Citrobacter species. The range of illnesses caused by Enterobacteriaceae is as diverse as the family, encompassing most body sites. Although most Enterobacteriaceae are intrinsically susceptible to antibiotics, there is potential for significant multi-drug resistance. Of particular recent concern has been the emergence of Enterobacteriaceae that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and even carbapenem-resistant strains.14

However, Enterobacteriaceae species susceptible to oral antimicrobials are often suitable candidates for oral BSI therapy. Among 106 patients with GNR BSI treated with a highly bioavailable oral antibiotic (eg, levofloxacin), the treatment failure rate was only 2% (versus 14% when an antimicrobial with only moderate or low bioavailability was selected).15 Oral treatment of Enterobacteriaceae BSIs secondary to urinary tract infection has been best studied. A prospective randomized, controlled trial evaluated oral versus intravenous ciprofloxacin amongst 141 patients with severe pyelonephritis or complicated urinary tract infections, in which the rate of bacteremia was 38%.16 Notably, patients with obstruction or renal abscess were excluded from the trial. No significant differences in microbiological failure or unsatisfactory clinical responses were found between the IV and oral treatment groups. Additionally, a Cochrane review reported that oral antibiotic therapy is no less effective than intravenous therapy for severe UTI, although data on BSI frequency were not provided.17

Resistance to fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin has been identified as a risk factor for GNR BSI oral treatment failure, highlighting the importance of confirming susceptibilities before committing to an oral treatment plan.18,19 Even ESBL Enterobacteriaceae can be considered for treatment with fluoroquinolones if susceptibilities allow.20

The ideal duration of therapy for GNR BSI is an area of active research. A recent retrospective trial showed no difference in all-cause mortality or recurrent BSI in GNR BSI treated for 8 versus 15 days.21 A recent meta-analysis suggested that 7 days of therapy was noninferior to a longer duration therapy (10–14 days) for pyelonephritis, in which a subset was bacteremic.22 However, another trial reported that short course therapy for GNR BSI (<7 days) is associated with higher risk of treatment failure.22 Further data are needed.

Gram-Negative Rods, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common pathogen, intrinsically resistant to many antimicrobials, and readily develops antimicrobial resistance during therapy. Fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and delafloxacin) are the only currently available oral agents with antipseudomonal activity. However, fluoroquinolones may not achieve blood concentrations appropriate for P. aeruginosa treatment at standard doses, while higher dose regimens may be associated with increased risk for undesirable side effects.24,25 Currently, given the minimal trial data comparing oral versus intravenous therapy for P. aeruginosa BSIs, and multiple studies indicating increased mortality when P. aeruginosa is treated inappropriately,26,27 we prefer a conservative approach and consider oral therapy a less-preferred option.

Evidence Regarding Bloodstream Infections due to Gram-Positive Cocci

The majority of bloodstream infections in the United States, and the resultant morbidity and mortality, are from gram-positive cocci (GPCs) such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus species.1

Gram-Positive Cocci, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Of the approximately 900,000 annual cases of S. pneumoniae infection in the United States, approximately 40,000 are complicated by BSI, with 70% of those cases being secondary to pneumococcal pneumonia.28 In studies on patients with pneumococcal pneumonia, bacteremic cases generally fare worse than those without bacteremia.29,30 However, several trials demonstrated comparable outcomes in the setting of bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia when switched early (within 3 days) from intravenous to oral antibiotics to complete a 7-day course.31,32 Before pneumococcal penicillin resistance became widespread, oral penicillin was shown to be effective, and remains an option for susceptible strains.33 It is worth noting, however, that other trials have shown a mortality benefit from treating bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia initially with dual-therapy including a β-lactam and macrolide such as azithromycin. This observation highlights the importance of knowing the final susceptibility data prior to consolidating to monotherapy with an oral agent, and that macrolides may have beneficial anti-inflammatory effects, though further research is needed.34,35

Although the evidence for treating bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia using a highly active and absorbable oral agent is fairly robust, S. pneumoniae BSI secondary to other sites of infection sites is less well studied and may require a more conservative approach.

Gram-Positive Cocci, β-hemolytic Streptococcus species

β-Hemolytic Streptococci include groups A to H, of which groups A (S. pyogenes) and B (S. agalactiae) are the most commonly implicated in BSIs.36 Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is classically associated with streptococcal pharyngitis and Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is associated with postpartum endometritis and neonatal meningitis, though both are virulent organisms with a potential to cause invasive infection throughout the body and in all age-groups. Up to 14% of GAS and 41% GBS BSIs have no clear source;37,38 given these are skin pathogens, such scenarios likely represent invasion via microabrasion. As β-hemolytic streptococcal BSI is often observed in the context of necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections, surgical source control is particularly important.39 GAS remains exquisitely susceptible to penicillin, and intravenous penicillin remains the mainstay for invasive disease; GBS has higher penicillin resistance rates than GAS.40 Clindamycin should be added when there is concern for severe disease or toxic shock.41 Unfortunately, oral penicillin is poorly bioavailable (approximately 50%), and there has been recent concern regarding inducible clindamycin resistance in GAS.42 Thus, oral penicillin V and/or clindamycin is a potentially risky strategy, with no clinical trials supporting this approach; however, they may be reasonable options in selected patients with source control and stable hemodynamics. Amoxicillin has high bioavailability (85%) and may be effective; however, there is lack of supporting data. Highly bioavailable agents such as levofloxacin and linezolid have GAS and GBS activity43 and might be expected to produce satisfactory outcomes. Because no clinical trials have compared these agents with intravenous therapy for BSI, caution is advised. Although bacteriostatic against Staphylococcus, linezolid is bactericidal against Streptococcus.44 Fluoroquinolone resistance amongst β-hemolytic Streptococcus is rare (approximately 0.5%) but does occur.45

Gram-Positive Cocci, Staphylococcus Species

Staphylococcus species include S. aureus (including methicillin susceptible and resistant strains: MSSA and MRSA, respectively) and coagulase-negative species, which include organisms such as S. epidermidis. S. aureus is the most common cause of BSI mortality in the United States,1 with mortality rates estimated at 20%–40% per episode.46 Infectious disease consultation has been associated with decreased mortality and is recommended.47 The guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of MRSA recommend the use of parenteral agents for BSI.48 It is important to consider if a patient with S. aureus BSI has infective endocarditis.

Oral antibiotic therapy for S. aureus BSI is not currently standard practice. Although trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) has favorable pharmacokinetics and case series of using it successfully for BSI exist,49 TMP-SMX showed inferior outcomes in a randomized trial comparing oral TMP-SMX with intravenous vancomycin in a series of 101 S. aureus infections.50 This observation has been replicated.51 Data on doxycycline or clindamycin for S. aureus BSI are limited, and IDSA guidelines advise against their use in this setting because they are predominantly bacteriostatic.48 Linezolid has favorable pharmacokinetics, with approximately 100% bioavailability, and S. aureus resistance to linezolid is rare.52 Several randomized trials have compared oral linezolid with intravenous vancomycin for S. aureus BSI; for instance, Stevens et al. randomized 460 patients with S. aureus infection (of whom 18% had BSI) to linezolid versus vancomycin and observed similar clinical cure rates.53 A pooled analysis showed oral linezolid was noninferior to vancomycin specifically for S. aureus BSI.54 However, long-term use is often limited by hematologic toxicity, peripheral or optic neuropathy (which can be permanent), and induced serotonin syndrome. Additionally, linezolid is bacteriostatic, not bactericidal against S. aureus. Using oral linezolid as a first-line option for S. aureus BSI would not be recommended; however, it may be used as a second-line treatment option in selected cases. Tedizolid has similar pharmacokinetics and spectrum of activity with fewer side effects; however, clinical data on its use for S. aureus BSI are lacking.55 Fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin and the newer agent delafloxacin have activity against S. aureus, including MRSA, but on-treatment emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance is a concern, and data on delafloxacin for BSI are lacking.56,57 Older literature suggested the combination of ciprofloxacin and rifampin was effective against right-sided S. aureus endocarditis,58 and other oral fluoroquinolone-rifamycin combinations have also been found to be effective59 However, this approach is currently not a standard therapy, nor is it widely used. Decisions on the duration of therapy for S. aureus BSI should be made in conjunction with an infectious diseases specialist; 14 days is currently regarded as a minimum.47,48

Published data regarding oral treatment of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) BSI are limited. Most CoNS bacteremia and up to 80% Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteremia represent blood culture contamination, though true infection from CoNS is not uncommon, particularly in patients with indwelling catheters.60 An exception is the CoNS species Staphylococcus lugdunensis, which is more virulent, and bacteremia with this organism usually warrants antibiotics. Oral antimicrobial therapy is currently not a standard treatment practice for CoNS BSI that is felt to represent true infection; however, linezolid has been successfully used in case series.61

Gram-Positive Cocci, Enterococcus

E. faecium and E. faecalis are commonly implicated in BSI.1 Similar to S. aureus, infective endocarditis must be ruled out when treating enterococcus BSI; a scoring system has been proposed to assist in deciding if such patients require echocardiography.62 Intravenous ampicillin is a preferred, highly effective agent for enterococci treatment when the organism is susceptible.44 However, oral ampicillin has poor bioavailability (50%), and data for its use in BSI are lacking. For susceptible strains, amoxicillin has comparable efficacy for enterococci and enhanced bioavailability (85%); high dose oral amoxicillin could be considered, but there is minimal clinical trial data to support this approach. Fluoroquinolones exhibit only modest activity against enterococci and would be an inferior choice for BSI.63 Although often sensitive to oral tetracyclines, data on their use in enterococcal BSI are insufficient. Nitrofurantoin can be used for susceptible enterococcal urinary tract infection; however, it does not achieve high blood concentrations and should not be used for BSI.

There is significant data comparing oral linezolid with intravenous daptomycin for vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) BSI. In a systematic review including 10 trials using 30-day all-cause mortality as the primary outcome, patients treated with daptomycin demonstrated higher odds of death (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.08–2.40) compared with those treated with linezolid.64 However, more recent data suggested that higher daptomycin doses than those used in these earlier trials resulted in improved VRE BSI outcomes.65 A subsequent study reported that VRE BSI treatment with linezolid is associated with significantly higher treatment failure and mortality compared with daptomycin therapy.66 Further research is needed, but should the side-effect profile of linezolid be tolerable, it remains an effective option for oral treatment of enterococcal BSIs.

Evidence Regarding Anaerobic Bacterial Blood Stream Infection

Anaerobic bacteria include Bacteroides, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Veillonella, and Clostridium. Anaerobes account for approximately 4% of bacterial BSIs, and are often seen in the context of polymicrobial infection.67 Given that anaerobes are difficult to recover, and that antimicrobial resistance testing is more labor intensive, antibiotic therapy choices are often made empirically.67 Unfortunately, antibiotic resistance amongst anaerobes is increasing.68 However, metronidazole remains highly active against a majority of anaerobes, with only a handful of treatment failures reported,69 and has a highly favorable pharmacokinetic profile for oral treatment. Oral metronidazole remains an effective choice for many anaerobic BSIs. Considering the polymicrobial nature of many anaerobic infections, source control is important, and concomitant GNR infection must be ruled out before using metronidazole monotherapy.

Clindamycin has significant anaerobic activity, but Bacteroides resistance has increased significantly in recent years, as high as 26%-44%.70 Amoxicillin-clavulanate has good anaerobic coverage, but bioavailability of clavulanate is limited (50%), making it inferior for BSI. Bioavailability is also limited for cephalosporins with anaerobic activity, such as cefuroxime. Moxifloxacin is a fluoroquinolone with some anaerobic coverage and a good oral pharmacokinetic profile, but Bacteroides resistance can be as high as 50%, making it a risky empiric choice.68

Conclusions

Bacterial BSIs are common and result in significant morbidity and mortality, with high associated healthcare costs. Although BSIs are traditionally treated with intravenous antimicrobials, many BSIs can be safely and effectively cured using oral antibiotics. When appropriately selected, oral antibiotics offer lower costs, fewer side effects, promote antimicrobial stewardship, and are easier for patients. Ultimately, the decision to use oral versus intravenous antibiotics must consider the characteristics of the pathogen, patient, and drug.

Disclosures

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

Bacterial bloodstream infections (BSIs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Approximately 600,000 BSI cases occur annually, resulting in 85,000 deaths,1 at a cost exceeding $1 billion.2 Traditionally, BSIs have been managed with intravenous antimicrobials, which rapidly achieve therapeutic blood concentrations, and are viewed as more potent than oral alternatives. Indeed, for acutely ill patients with bacteremia and sepsis, timely intravenous antimicrobials are lifesaving.3

However, whether intravenous antimicrobials are essential for the entire treatment course in BSIs, particularly for uncomplicated episodes, is controversial. Patients that are clinically stable or have been stabilized after an initial septic presentation may be appropriate candidates for treatment with oral antimicrobials. There are costs and risks associated with extended courses of intravenous agents, such as the necessity for long-term intravenous catheters, which entail risks for procedural complications, secondary infections, and thrombosis. A prospective study of 192 peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) episodes reported an overall complication rate of 30.2%, including central line-associated BSIs (CLABSI) or venous thrombosis.4 Other studies also identified high rates of thrombosis5 and PICC-related CLABSI, particularly in patients with malignancy, where sepsis-related complications approach 25%.6 Additionally, appropriate care of indwelling catheters requires significant financial and healthcare resources.

Oral antimicrobial therapy for bacterial BSIs offers several potential benefits. Direct economic and healthcare workforce savings are expected to be significant, and procedural and catheter-related complications would be eliminated.7 Moreover, oral therapy provides antimicrobial stewardship by reducing the use of broad-spectrum intravenous agents.8 Recent infectious disease “Choosing Wisely” initiatives recommend clinicians “prefer oral formulations of highly bioavailable antimicrobials whenever possible”,9 and this approach is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention antibiotic stewardship program.10 However, the expected savings and benefits of oral therapy would be lost should they be less effective and result in treatment failure or relapse of the primary BSI. Pathogen susceptibility, gastrointestinal absorption, oral bioavailability, patient tolerability, and adherence with therapy need to be carefully considered before choosing oral antimicrobials. Thus, oral antimicrobial therapy for BSI should be utilized in carefully selected circumstances.

In this narrative review, we highlight areas where oral therapy is safe and effective in treating bloodstream infections, as well as offer guidance to clinicians managing patients experiencing BSI. Given the lack of robust clinical trials on this subject, the evidence for performing a systematic review was insufficient. Thus, the articles and recommendations cited in this review were selected based on the authors’ experiences to represent the best available evidence.

Infection Source Control

Pathogen and Antimicrobial Factors

Patient Factors

Evidence Regarding Bloodstream Infections due to Gram-Negative Rods

BSIs due to gram-negative rods (GNRs) are common and cause significant morbidity and mortality. GNRs represent a broad and diverse array of pathogens. We focus on the Enterobacteriaceae family and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, because they are frequently encountered in clinical practice.1

Gram-Negative Rods, Enterobacteriaceae Family

The Enterobacteriaceae family includes Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Proteus, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Citrobacter species. The range of illnesses caused by Enterobacteriaceae is as diverse as the family, encompassing most body sites. Although most Enterobacteriaceae are intrinsically susceptible to antibiotics, there is potential for significant multi-drug resistance. Of particular recent concern has been the emergence of Enterobacteriaceae that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and even carbapenem-resistant strains.14

However, Enterobacteriaceae species susceptible to oral antimicrobials are often suitable candidates for oral BSI therapy. Among 106 patients with GNR BSI treated with a highly bioavailable oral antibiotic (eg, levofloxacin), the treatment failure rate was only 2% (versus 14% when an antimicrobial with only moderate or low bioavailability was selected).15 Oral treatment of Enterobacteriaceae BSIs secondary to urinary tract infection has been best studied. A prospective randomized, controlled trial evaluated oral versus intravenous ciprofloxacin amongst 141 patients with severe pyelonephritis or complicated urinary tract infections, in which the rate of bacteremia was 38%.16 Notably, patients with obstruction or renal abscess were excluded from the trial. No significant differences in microbiological failure or unsatisfactory clinical responses were found between the IV and oral treatment groups. Additionally, a Cochrane review reported that oral antibiotic therapy is no less effective than intravenous therapy for severe UTI, although data on BSI frequency were not provided.17

Resistance to fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin has been identified as a risk factor for GNR BSI oral treatment failure, highlighting the importance of confirming susceptibilities before committing to an oral treatment plan.18,19 Even ESBL Enterobacteriaceae can be considered for treatment with fluoroquinolones if susceptibilities allow.20

The ideal duration of therapy for GNR BSI is an area of active research. A recent retrospective trial showed no difference in all-cause mortality or recurrent BSI in GNR BSI treated for 8 versus 15 days.21 A recent meta-analysis suggested that 7 days of therapy was noninferior to a longer duration therapy (10–14 days) for pyelonephritis, in which a subset was bacteremic.22 However, another trial reported that short course therapy for GNR BSI (<7 days) is associated with higher risk of treatment failure.22 Further data are needed.

Gram-Negative Rods, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common pathogen, intrinsically resistant to many antimicrobials, and readily develops antimicrobial resistance during therapy. Fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and delafloxacin) are the only currently available oral agents with antipseudomonal activity. However, fluoroquinolones may not achieve blood concentrations appropriate for P. aeruginosa treatment at standard doses, while higher dose regimens may be associated with increased risk for undesirable side effects.24,25 Currently, given the minimal trial data comparing oral versus intravenous therapy for P. aeruginosa BSIs, and multiple studies indicating increased mortality when P. aeruginosa is treated inappropriately,26,27 we prefer a conservative approach and consider oral therapy a less-preferred option.

Evidence Regarding Bloodstream Infections due to Gram-Positive Cocci

The majority of bloodstream infections in the United States, and the resultant morbidity and mortality, are from gram-positive cocci (GPCs) such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus species.1

Gram-Positive Cocci, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Of the approximately 900,000 annual cases of S. pneumoniae infection in the United States, approximately 40,000 are complicated by BSI, with 70% of those cases being secondary to pneumococcal pneumonia.28 In studies on patients with pneumococcal pneumonia, bacteremic cases generally fare worse than those without bacteremia.29,30 However, several trials demonstrated comparable outcomes in the setting of bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia when switched early (within 3 days) from intravenous to oral antibiotics to complete a 7-day course.31,32 Before pneumococcal penicillin resistance became widespread, oral penicillin was shown to be effective, and remains an option for susceptible strains.33 It is worth noting, however, that other trials have shown a mortality benefit from treating bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia initially with dual-therapy including a β-lactam and macrolide such as azithromycin. This observation highlights the importance of knowing the final susceptibility data prior to consolidating to monotherapy with an oral agent, and that macrolides may have beneficial anti-inflammatory effects, though further research is needed.34,35

Although the evidence for treating bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia using a highly active and absorbable oral agent is fairly robust, S. pneumoniae BSI secondary to other sites of infection sites is less well studied and may require a more conservative approach.

Gram-Positive Cocci, β-hemolytic Streptococcus species

β-Hemolytic Streptococci include groups A to H, of which groups A (S. pyogenes) and B (S. agalactiae) are the most commonly implicated in BSIs.36 Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is classically associated with streptococcal pharyngitis and Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is associated with postpartum endometritis and neonatal meningitis, though both are virulent organisms with a potential to cause invasive infection throughout the body and in all age-groups. Up to 14% of GAS and 41% GBS BSIs have no clear source;37,38 given these are skin pathogens, such scenarios likely represent invasion via microabrasion. As β-hemolytic streptococcal BSI is often observed in the context of necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections, surgical source control is particularly important.39 GAS remains exquisitely susceptible to penicillin, and intravenous penicillin remains the mainstay for invasive disease; GBS has higher penicillin resistance rates than GAS.40 Clindamycin should be added when there is concern for severe disease or toxic shock.41 Unfortunately, oral penicillin is poorly bioavailable (approximately 50%), and there has been recent concern regarding inducible clindamycin resistance in GAS.42 Thus, oral penicillin V and/or clindamycin is a potentially risky strategy, with no clinical trials supporting this approach; however, they may be reasonable options in selected patients with source control and stable hemodynamics. Amoxicillin has high bioavailability (85%) and may be effective; however, there is lack of supporting data. Highly bioavailable agents such as levofloxacin and linezolid have GAS and GBS activity43 and might be expected to produce satisfactory outcomes. Because no clinical trials have compared these agents with intravenous therapy for BSI, caution is advised. Although bacteriostatic against Staphylococcus, linezolid is bactericidal against Streptococcus.44 Fluoroquinolone resistance amongst β-hemolytic Streptococcus is rare (approximately 0.5%) but does occur.45

Gram-Positive Cocci, Staphylococcus Species

Staphylococcus species include S. aureus (including methicillin susceptible and resistant strains: MSSA and MRSA, respectively) and coagulase-negative species, which include organisms such as S. epidermidis. S. aureus is the most common cause of BSI mortality in the United States,1 with mortality rates estimated at 20%–40% per episode.46 Infectious disease consultation has been associated with decreased mortality and is recommended.47 The guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of MRSA recommend the use of parenteral agents for BSI.48 It is important to consider if a patient with S. aureus BSI has infective endocarditis.

Oral antibiotic therapy for S. aureus BSI is not currently standard practice. Although trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) has favorable pharmacokinetics and case series of using it successfully for BSI exist,49 TMP-SMX showed inferior outcomes in a randomized trial comparing oral TMP-SMX with intravenous vancomycin in a series of 101 S. aureus infections.50 This observation has been replicated.51 Data on doxycycline or clindamycin for S. aureus BSI are limited, and IDSA guidelines advise against their use in this setting because they are predominantly bacteriostatic.48 Linezolid has favorable pharmacokinetics, with approximately 100% bioavailability, and S. aureus resistance to linezolid is rare.52 Several randomized trials have compared oral linezolid with intravenous vancomycin for S. aureus BSI; for instance, Stevens et al. randomized 460 patients with S. aureus infection (of whom 18% had BSI) to linezolid versus vancomycin and observed similar clinical cure rates.53 A pooled analysis showed oral linezolid was noninferior to vancomycin specifically for S. aureus BSI.54 However, long-term use is often limited by hematologic toxicity, peripheral or optic neuropathy (which can be permanent), and induced serotonin syndrome. Additionally, linezolid is bacteriostatic, not bactericidal against S. aureus. Using oral linezolid as a first-line option for S. aureus BSI would not be recommended; however, it may be used as a second-line treatment option in selected cases. Tedizolid has similar pharmacokinetics and spectrum of activity with fewer side effects; however, clinical data on its use for S. aureus BSI are lacking.55 Fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin and the newer agent delafloxacin have activity against S. aureus, including MRSA, but on-treatment emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance is a concern, and data on delafloxacin for BSI are lacking.56,57 Older literature suggested the combination of ciprofloxacin and rifampin was effective against right-sided S. aureus endocarditis,58 and other oral fluoroquinolone-rifamycin combinations have also been found to be effective59 However, this approach is currently not a standard therapy, nor is it widely used. Decisions on the duration of therapy for S. aureus BSI should be made in conjunction with an infectious diseases specialist; 14 days is currently regarded as a minimum.47,48

Published data regarding oral treatment of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) BSI are limited. Most CoNS bacteremia and up to 80% Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteremia represent blood culture contamination, though true infection from CoNS is not uncommon, particularly in patients with indwelling catheters.60 An exception is the CoNS species Staphylococcus lugdunensis, which is more virulent, and bacteremia with this organism usually warrants antibiotics. Oral antimicrobial therapy is currently not a standard treatment practice for CoNS BSI that is felt to represent true infection; however, linezolid has been successfully used in case series.61

Gram-Positive Cocci, Enterococcus

E. faecium and E. faecalis are commonly implicated in BSI.1 Similar to S. aureus, infective endocarditis must be ruled out when treating enterococcus BSI; a scoring system has been proposed to assist in deciding if such patients require echocardiography.62 Intravenous ampicillin is a preferred, highly effective agent for enterococci treatment when the organism is susceptible.44 However, oral ampicillin has poor bioavailability (50%), and data for its use in BSI are lacking. For susceptible strains, amoxicillin has comparable efficacy for enterococci and enhanced bioavailability (85%); high dose oral amoxicillin could be considered, but there is minimal clinical trial data to support this approach. Fluoroquinolones exhibit only modest activity against enterococci and would be an inferior choice for BSI.63 Although often sensitive to oral tetracyclines, data on their use in enterococcal BSI are insufficient. Nitrofurantoin can be used for susceptible enterococcal urinary tract infection; however, it does not achieve high blood concentrations and should not be used for BSI.

There is significant data comparing oral linezolid with intravenous daptomycin for vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) BSI. In a systematic review including 10 trials using 30-day all-cause mortality as the primary outcome, patients treated with daptomycin demonstrated higher odds of death (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.08–2.40) compared with those treated with linezolid.64 However, more recent data suggested that higher daptomycin doses than those used in these earlier trials resulted in improved VRE BSI outcomes.65 A subsequent study reported that VRE BSI treatment with linezolid is associated with significantly higher treatment failure and mortality compared with daptomycin therapy.66 Further research is needed, but should the side-effect profile of linezolid be tolerable, it remains an effective option for oral treatment of enterococcal BSIs.

Evidence Regarding Anaerobic Bacterial Blood Stream Infection

Anaerobic bacteria include Bacteroides, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Veillonella, and Clostridium. Anaerobes account for approximately 4% of bacterial BSIs, and are often seen in the context of polymicrobial infection.67 Given that anaerobes are difficult to recover, and that antimicrobial resistance testing is more labor intensive, antibiotic therapy choices are often made empirically.67 Unfortunately, antibiotic resistance amongst anaerobes is increasing.68 However, metronidazole remains highly active against a majority of anaerobes, with only a handful of treatment failures reported,69 and has a highly favorable pharmacokinetic profile for oral treatment. Oral metronidazole remains an effective choice for many anaerobic BSIs. Considering the polymicrobial nature of many anaerobic infections, source control is important, and concomitant GNR infection must be ruled out before using metronidazole monotherapy.

Clindamycin has significant anaerobic activity, but Bacteroides resistance has increased significantly in recent years, as high as 26%-44%.70 Amoxicillin-clavulanate has good anaerobic coverage, but bioavailability of clavulanate is limited (50%), making it inferior for BSI. Bioavailability is also limited for cephalosporins with anaerobic activity, such as cefuroxime. Moxifloxacin is a fluoroquinolone with some anaerobic coverage and a good oral pharmacokinetic profile, but Bacteroides resistance can be as high as 50%, making it a risky empiric choice.68

Conclusions

Bacterial BSIs are common and result in significant morbidity and mortality, with high associated healthcare costs. Although BSIs are traditionally treated with intravenous antimicrobials, many BSIs can be safely and effectively cured using oral antibiotics. When appropriately selected, oral antibiotics offer lower costs, fewer side effects, promote antimicrobial stewardship, and are easier for patients. Ultimately, the decision to use oral versus intravenous antibiotics must consider the characteristics of the pathogen, patient, and drug.

Disclosures

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

1. Goto M, Al-Hasan MN. Overall burden of bloodstream infection and nosocomial bloodstream infection in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(6):501-509. PubMed

2. Kilgore M, Brossette S. Cost of bloodstream infections. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(10):S172.e1-3. PubMed

3. Youkee D, Hulme W, Roberts T, Daniels R, Nutbeam T, Keep J. Time Matters: Antibiotic Timing in Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(10):e1016-1017. PubMed

4. Grau D, Clarivet B, Lotthé A, Bommart S, Parer S. Complications with peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) used in hospitalized patients and outpatients: a prospective cohort study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;28;6:18. PubMed

5. Allen AW, Megargell JL, Brown DB, Lynch FC, Singh H, Singh Y, Waybill PN. Venous Thrombosis Associated with the Placement of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(10):1309-1314. PubMed

6. Cheong K, Perry D, Karapetis C, Koczwara B. High rate of complications associated with peripherally inserted central venous catheters in patients with solid tumours. Intern Med J. 2004;34(5):234-238. PubMed

7. Cunha BA. Oral antibiotic therapy of serious systemic infections. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(6):1197-1222. PubMed

8. Cyriac JM, James E. Switch over from intravenous to oral therapy: A concise overview. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2014;5(2):83-87. PubMed

9. Lehmann C, Berner R, Bogner JR, et al. The “Choosing Wisely” initiative in infectious diseases. Infection. 2017;45(3):263-268. PubMed

10. Lehmann C, Berner R, Bogner JR, et al. The “Choosing Wisely” initiative in infectious diseases. Infection. 2017;45(3):263-268. PubMed

11. Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1-45. PubMed

12. Spellberg B, Lipsky BA. Systemic antibiotic therapy for chronic osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(3):393-407. PubMed

13. Cua YM, Kripalani S. Medication Use in the Transition from Hospital to Home. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(2):136. PubMed

14. Paterson DL. Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria: Enterobacteriaceae. Am J Med. 2006; 119(6):S20-28.

15. Kutob LF, Justo JA, Bookstaver PB, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Effectiveness of oral antibiotics for definitive therapy of Gram-negative bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(5):498-503. PubMed

16. Mombelli G, Pezzoli R, Pinoja-Lutz G, Monotti R, Marone C, Franciolli M Oral vs Intravenous Ciprofloxacin in the Initial Empirical Management of Severe Pyelonephritis or Complicated Urinary Tract Infections: A Prospective Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(1):53-58. PubMed

17. Pohl A. Modes of administration of antibiotics for symptomatic severe urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003237. PubMed

18. Brigmon MM, Bookstaver PB, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Impact of fluoroquinolone resistance in Gram-negative bloodstream infections on healthcare utilization. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(9):843-849. PubMed

19. Ortega M, Marco F, Soriano A, et al. Analysis of 4758 Escherichia coli bacteraemia episodes: predictive factors for isolation of an antibiotic-resistant strain and their impact on the outcome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(3):568-574. PubMed

20. Lo CL, Lee CC, Li CW, et al. Fluoroquinolone therapy for bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2017;50(3):355-361. PubMed

21. Chotiprasitsakul D, Han JH, Cosgrove SE, et al. Comparing the Outcomes of Adults With Enterobacteriaceae Bacteremia Receiving Short-Course Versus Prolonged-Course Antibiotic Therapy in a Multicenter, Propensity Score–Matched Cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2017; cix767. doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix767 PubMed

22. Eliakim-Raz N, Yahav D, Paul M, Leibovici L. Duration of antibiotic treatment for acute pyelonephritis and septic urinary tract infection-- 7 days or less versus longer treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(10):2183-2191. PubMed

23. Nelson AN, Justo JA, Bookstaver PB, Kohn J, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated Gram-negative bloodstream infections. Infection. 2017;45(5):613-620. PubMed

24. Zelenitsky S, Ariano R, Harding G, Forrest A. Evaluating Ciprofloxacin Dosing for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection by Using Clinical Outcome-Based Monte Carlo Simulations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(10):4009-4014. PubMed

25. Cazaubon Y, Bourguignon L, Goutelle S, Martin O, Maire P, Ducher M. Are ciprofloxacin dosage regimens adequate for antimicrobial efficacy and prevention of resistance? Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection in elderly patients as a simulation case study. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2015;29(6):615-624. PubMed

26. Micek ST, Lloyd AE, Ritchie DJ, Reichley RM, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bloodstream Infection: Importance of Appropriate Initial Antimicrobial Treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(4):1306-1311. PubMed

27. Chamot E, Boffi El Amari E, Rohner P, Van Delden C. Effectiveness of Combination Antimicrobial Therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(9):2756-2764. PubMed

28. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) Emerging Infections Program Network Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/spneu13.pdf. Published November, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2017.

29. Brandenburg JA, Marrie TJ, Coley CM, et al. Clinical presentation, processes and outcomes of care for patients with pneumococcal pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(9):638-646. PubMed

30. Musher DM, Alexandraki I, Graviss EA, et al. Bacteremic and nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. A prospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79(4):210-221. PubMed

31. Ramirez JA, Bordon J. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with bacteremic community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161(6):848-850. PubMed

32. Oosterheert JJ, Bonten MJM, Schneider MME, et al. Effectiveness of early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in severe community acquired pneumonia: multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;333(7580):1193. PubMed

33. Austrian R, Winston AL. The efficacy of penicillin V (phenoxymethyl-penicillin) in the treatment of mild and of moderately severe pneumococcal pneumonia. Am J Med Sci. 1956;232(6):624-628. PubMed

34. Waterer GW, Somes GW, Wunderink RG. Monotherapy May Be Suboptimal for Severe Bacteremic Pneumococcal Pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161(15):1837-1842. PubMed

35. Baddour LM, Yu VL, Klugman KP, et al. International Pneumococcal Study Group. Combination antibiotic therapy lowers mortality among severely ill patients with pneumococcal bacteremia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):440-444. PubMed

36. Sylvetsky N, Raveh D, Schlesinger Y, Rudensky B, Yinnon AM. Bacteremia due to beta-hemolytic streptococcus group g: increasing incidence and clinical characteristics of patients. Am J Med. 2002;112(8):622-626. PubMed

37. Davies HD, McGeer A, Schwartz B, Green, et al; Ontario Group A Streptococcal Study Group. Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(8):547-554. PubMed

38. Farley MM, Harvey C, Stull T, et al. A Population-Based Assessment of Invasive Disease Due to Group B Streptococcus in Nonpregnant Adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(25):1807-1811. PubMed

39. Nelson GE, Pondo T, Toews KA, et al. Epidemiology of Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in the United States, 2005-2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):478-486. PubMed