User login

Multiple Primary Atypical Vascular Lesions Occurring in the Same Breast

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

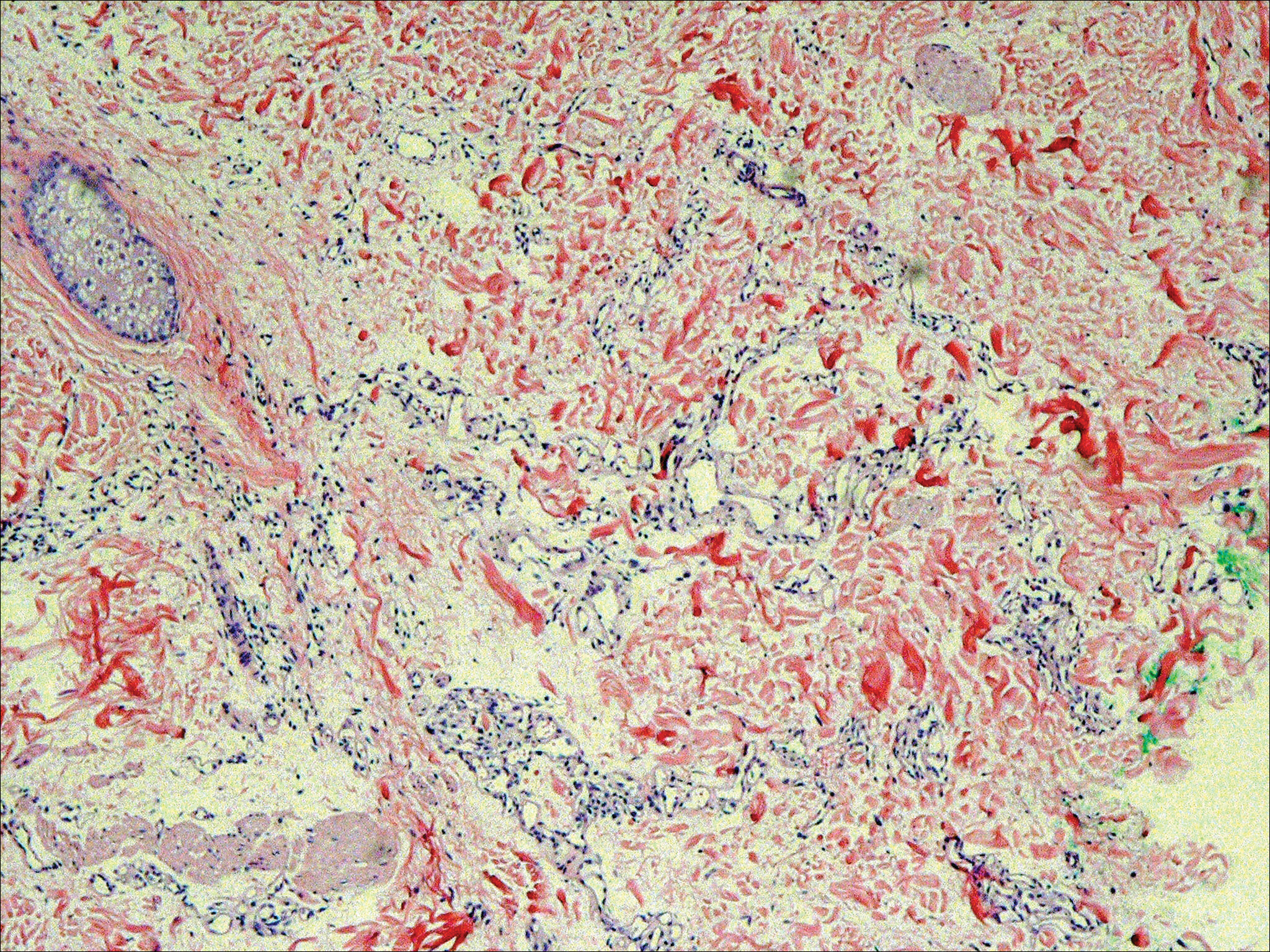

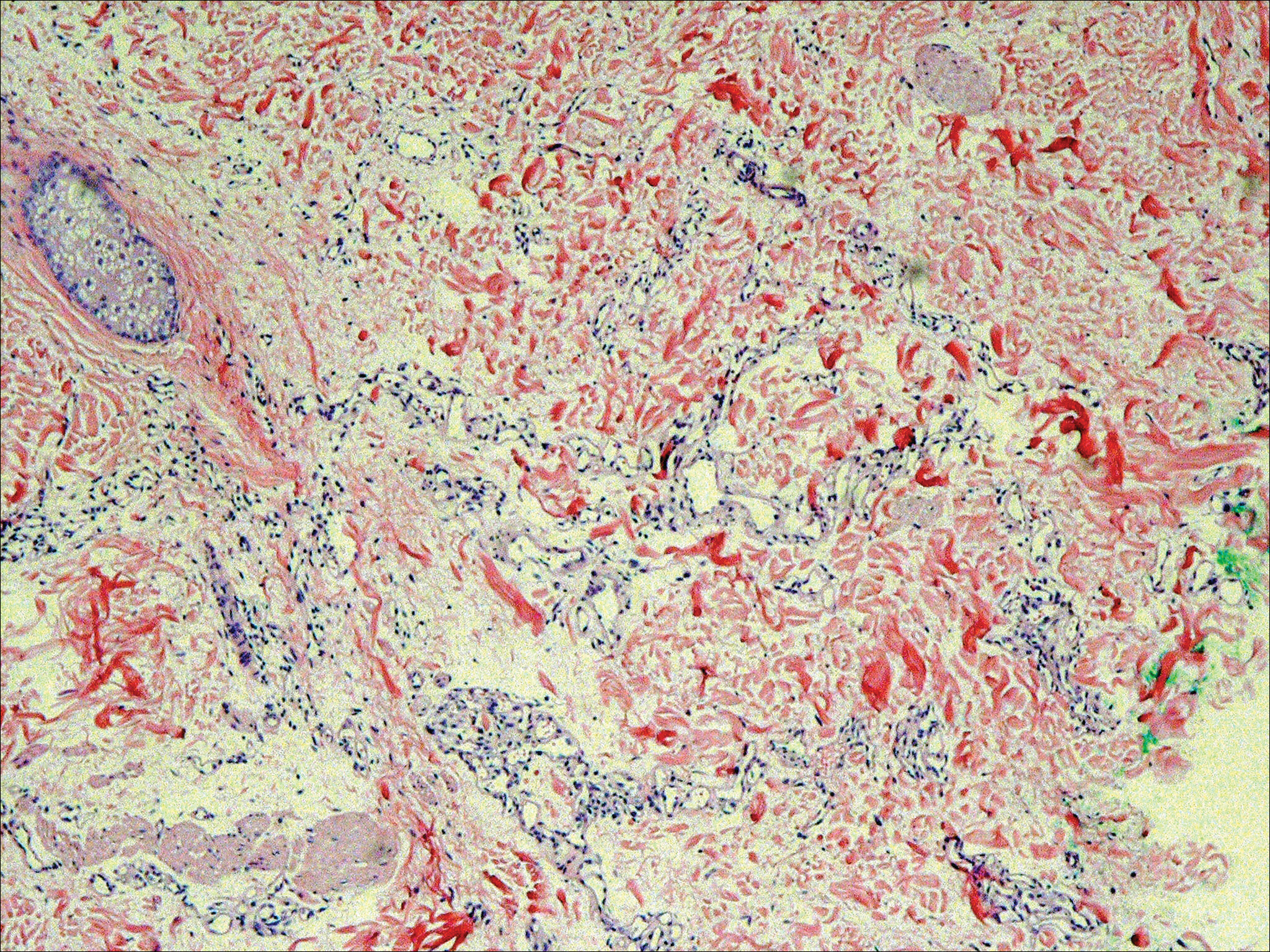

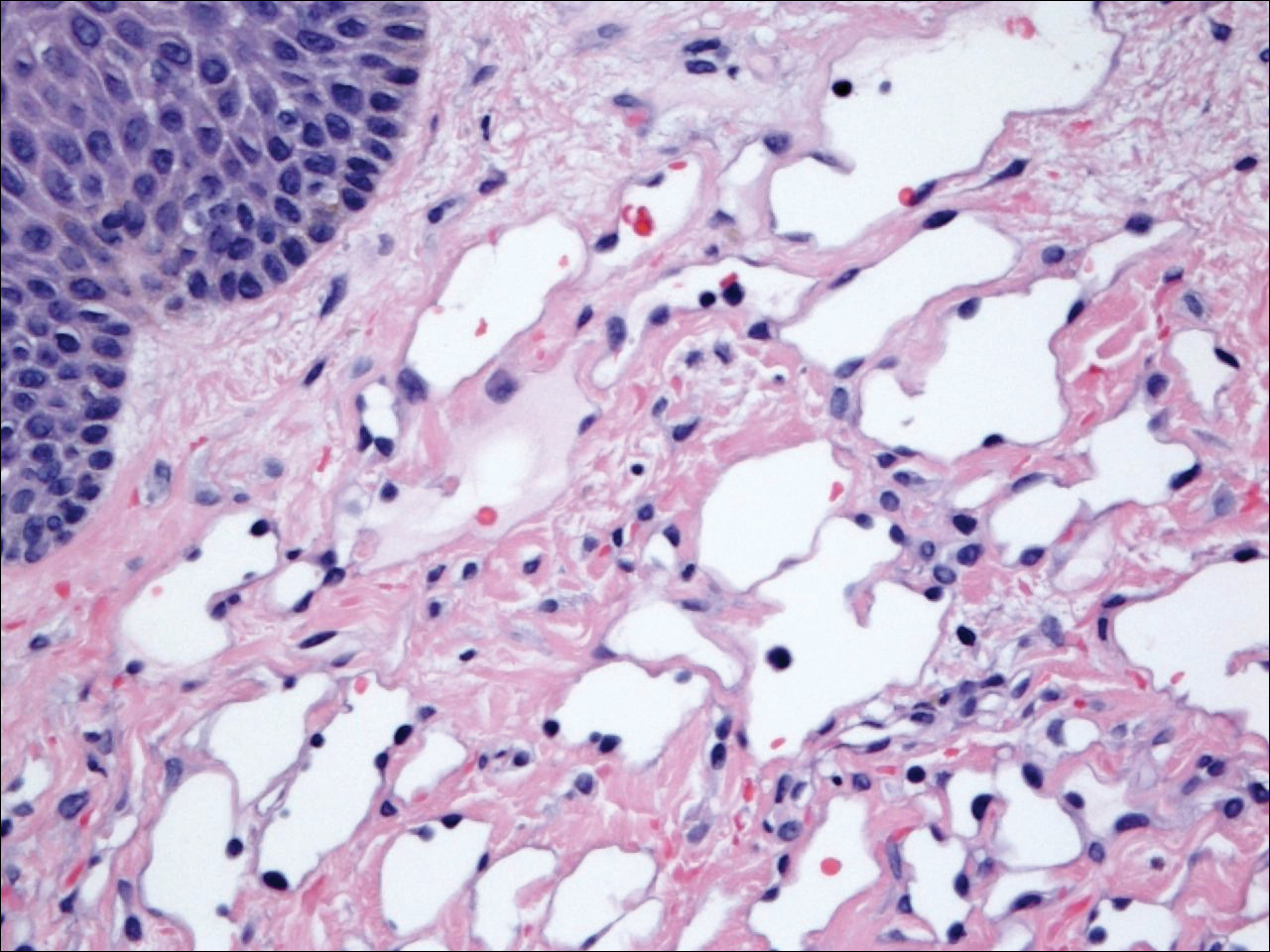

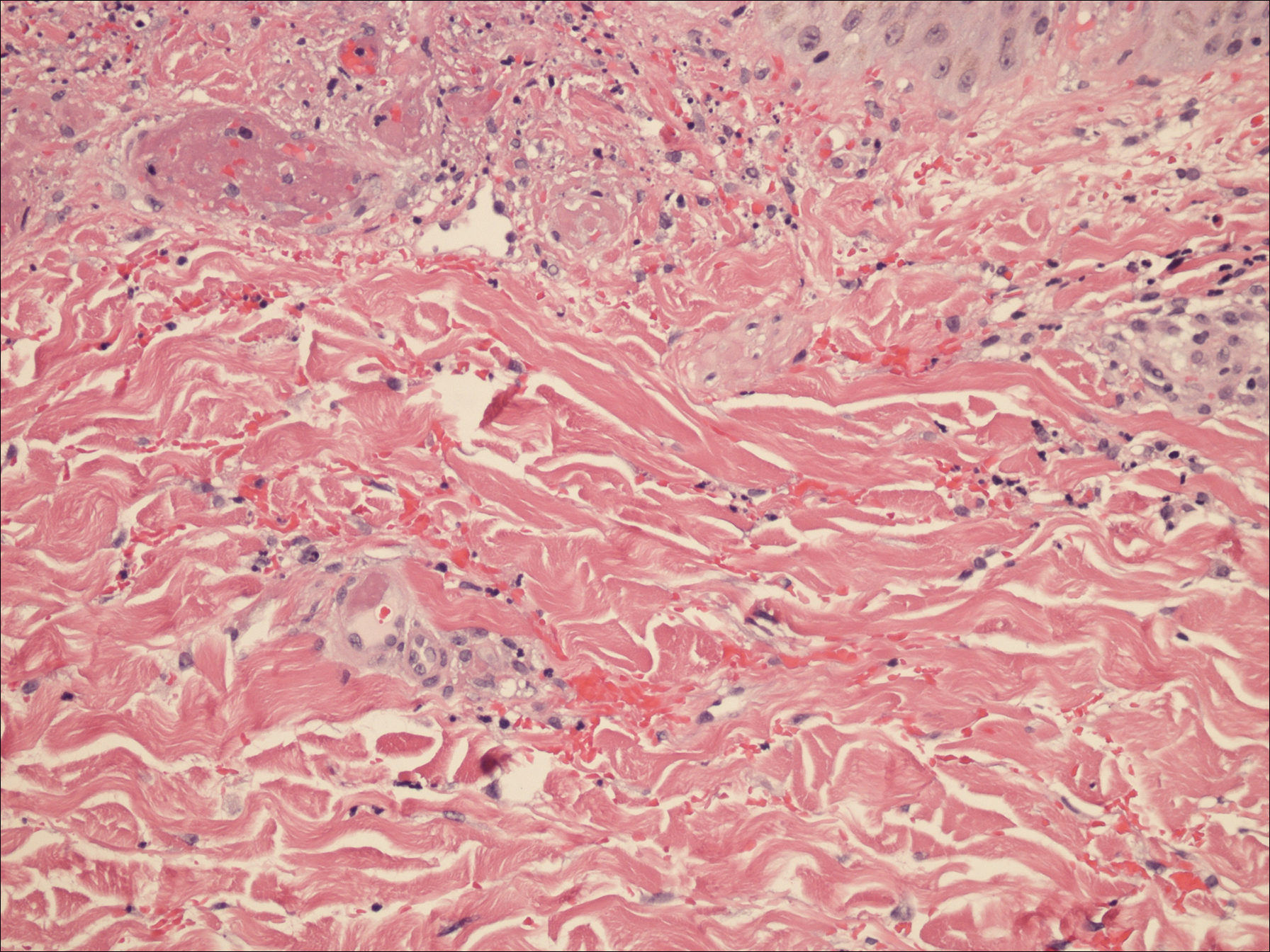

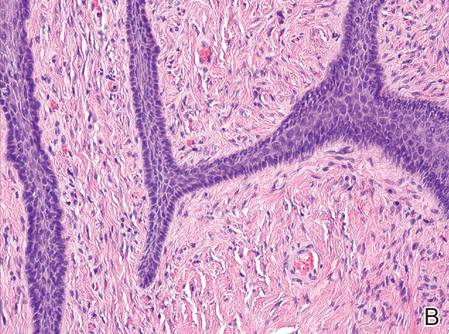

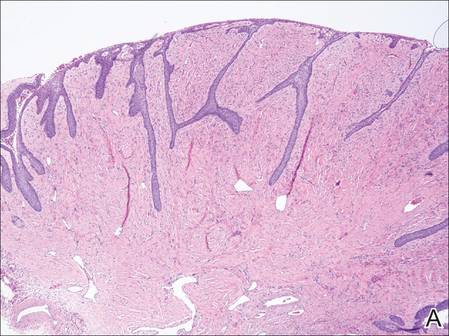

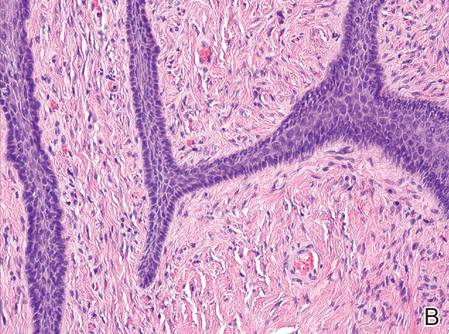

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

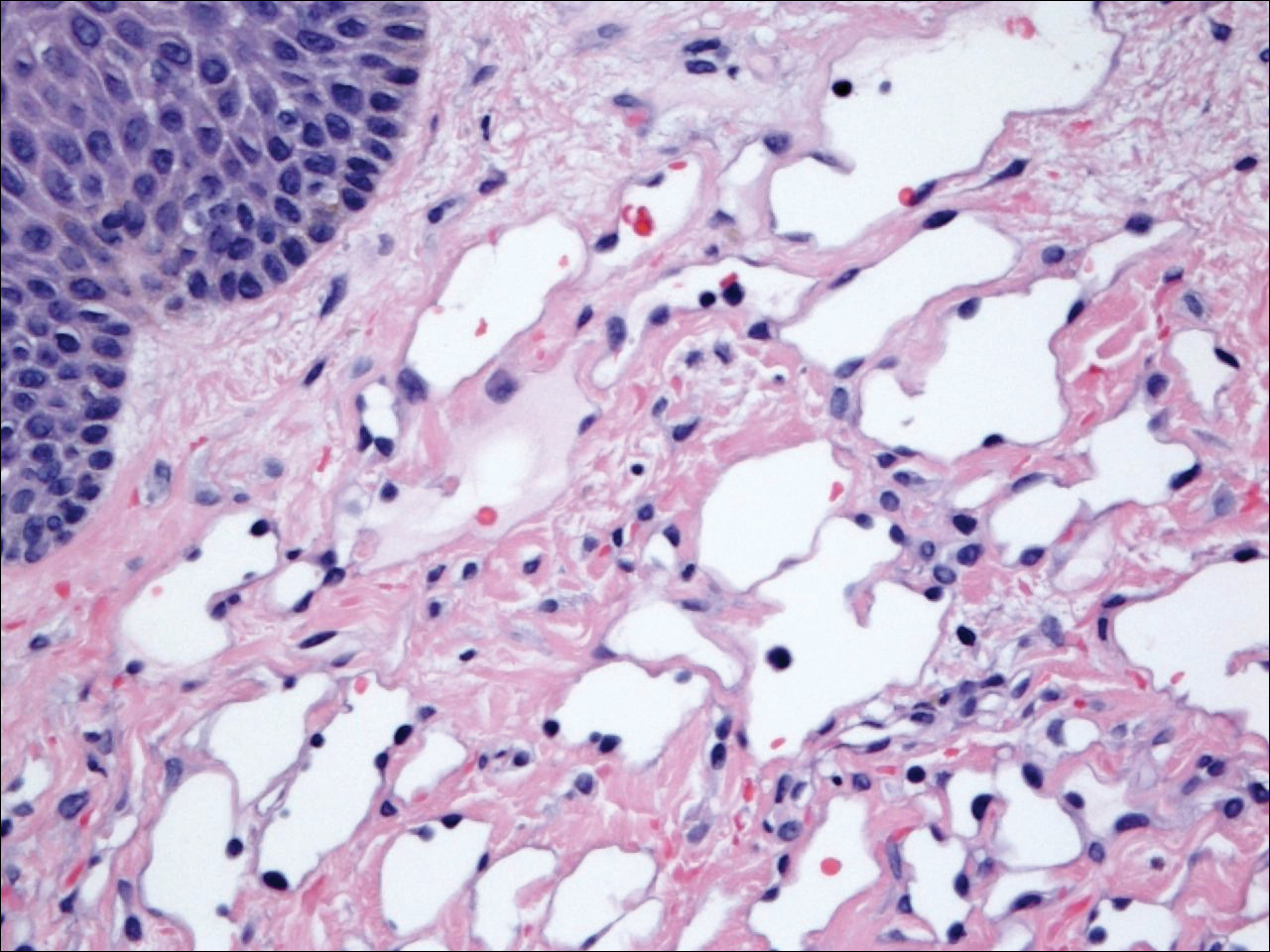

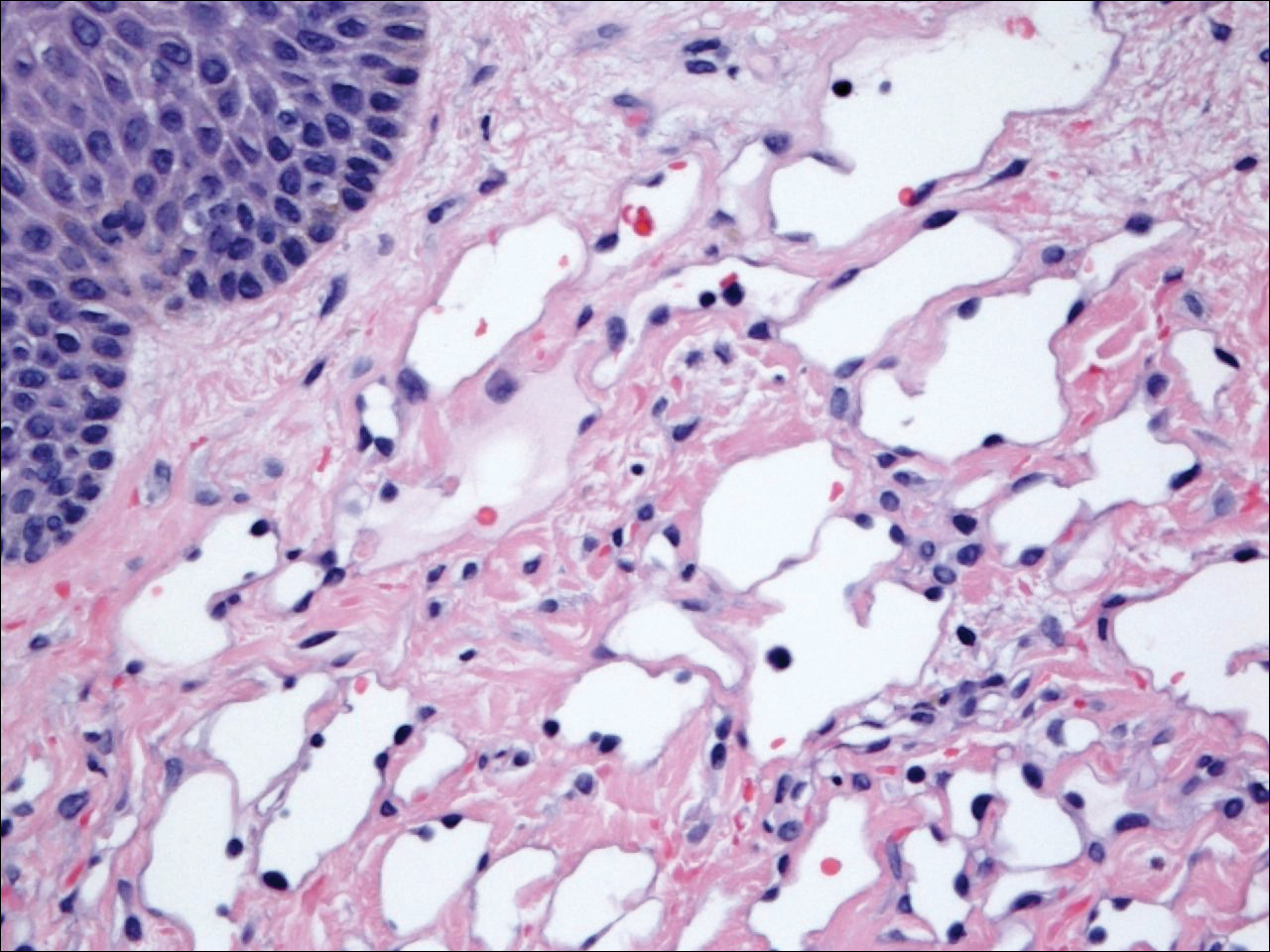

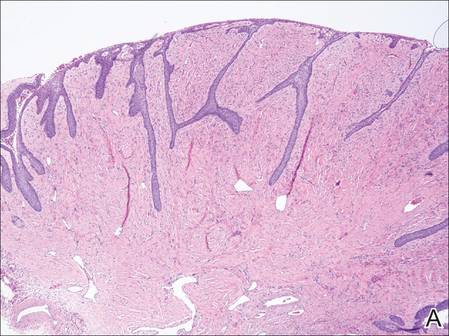

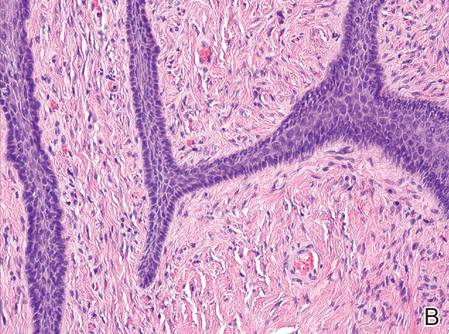

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

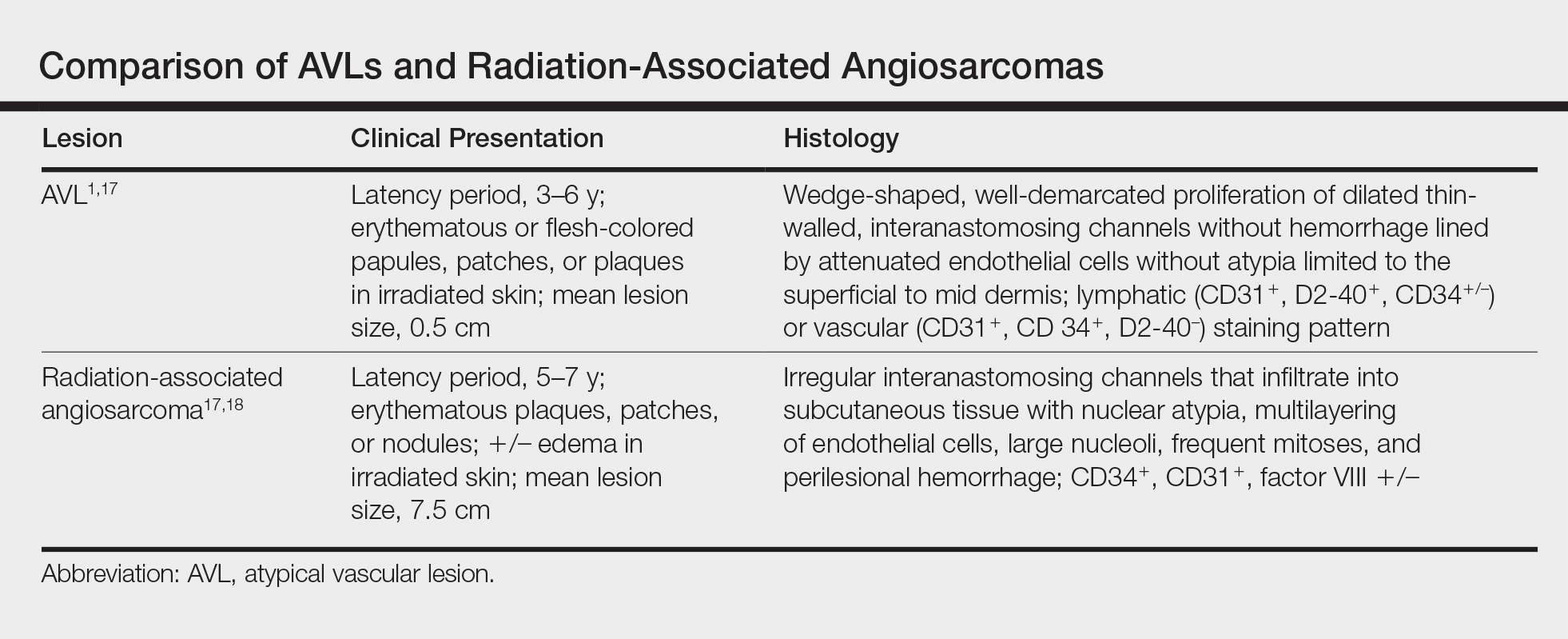

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast are rare cutaneous vascular proliferations that present as erythematous, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules, patches, or plaques in women who have undergone radiation treatment for breast carcinoma.1,2 These lesions most commonly develop in the irradiated area within 3 to 6 years following radiation treatment.3

Various terms have been used to describe AVLs in the literature, including atypical hemangiomas, benign lymphangiomatous papules, benign lymphangioendotheliomas, lymphangioma circumscriptum, and acquired progressive lymphangiomas, suggesting benign behavior.4-10 However, their identity as benign lesions has been a source of controversy, with some investigators proposing that AVLs may be a precursor lesion to postirradiation angiosarcoma.2 Research has addressed if there are markers that can predict AVL types that are more likely to develop into angiosarcomas.1 Although most clinicians treat AVLs with complete excision, there currently are no specific guidelines to direct this practice.

We report the case of a patient with a history of 1 AVL that was excised who developed 3 additional AVLs in the same breast over the course of 15 months.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of obesity, hypertension, and infiltrating ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast (grade 2, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive) underwent a right breast lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection. Three months later, she underwent re-excision for positive margins and started adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen. One month later, she began external beam radiation therapy and received a total dose of 6040 cGy over the course of 9 weeks (34 total treatments).

The patient presented to an outside dermatology clinic 2 years after completing external beam radiation therapy for evaluation of a new pink nodule on the right mid breast. The nodule was biopsied and discovered to be an AVL. Pathology showed an anastomosing proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels mainly located in the superficial dermis with notable endothelial nuclear atypia and hyperchromasia. There were several tiny foci with the beginnings of multilayering with prominent endothelial atypia (Figure 1). She underwent complete excision for this AVL with negative margins.

Six months after the initial AVL diagnosis, she presented to our dermatology clinic with another asymptomatic red bump on the right breast. On physical examination, a 4-mm firm, erythematous, well-circumscribed papule was noted on the medial aspect of the right breast along with a similar-appearing 4-mm papule on the right lateral aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient was unsure of the duration of the second lesion but felt that it had been present at least as long as the other lesion. Both lesions clinically resembled typical capillary hemangiomas. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the right medial breast was performed and revealed enlarged vessels and capillaries in the upper dermis lined by endothelial cells with focal prominent nuclei without necrosis, overt atypia, mitosis, or tufting (Figure 3). Immunostaining was positive for CD34, factor VIII antigen, podoplanin (D2-40), and CD31, and negative for cytokeratin 7 and pankeratin. This staining was compatible with a lymphatic-type AVL.1 A diagnosis of AVL was made and complete excision with clear margins was performed. At the time of this excision, a biopsy of the right lateral breast was performed revealing thin-walled, dilated vascular channels in the superficial dermis with architecturally atypical angulated outlines, mild endothelial nuclear atypia, and hyperchromasia without endothelial multilayering. Clear margins were noted on the biopsy, but the patient subsequently declined re-excision of this third AVL.

During a subsequent follow-up visit 9 months later, the patient was noted to have a 2-mm red, vascular-appearing papule on the right upper medial breast (Figure 2). A 6-mm biopsy was performed and revealed thin-walled vascular channels in the superficial dermis with endothelial nuclear atypia consistent with an AVL.

Comment

Fineberg and Rosen8 were the first to describe AVLs in their 1994 study of 4 women with cutaneous vascular proliferations that developed after radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer. They concluded that these AVLs were benign lesions distinct from angiosarcomas.8 However, further research has challenged the benign nature of AVLs. In 2005, Brenn and Fletcher2 studied 42 women diagnosed with either angiosarcoma or atypical radiation-associated cutaneous vascular lesions. They suggested that AVLs resided on the same spectrum as angiosarcomas and that AVLs may be precursor lesions to angiosarcomas.2 Furthermore, Hildebrandt et al11 in 2001 and Di Tommaso and Fabbri12 in 2003 published case reports of individual patients who developed an angiosarcoma from a preexisting AVL.

The controversy continued when Patton et al1 published a study in 2008 in which 32 cases of AVLs were reviewed. In this study, 2 histologic types of AVLs were described: vascular type and lymphatic type. Vascular-type AVLs are characterized by irregularly dispersed, pericyte-invested, capillary-sized vessels within the papillary or reticular dermis that often are associated with extravasated erythrocytes or hemosiderin. On the other hand, lymphatic-type AVLs display thin-walled, variably anastomosing, lymphatic vessels lined by attenuated or slightly protuberant endothelial cells. These subtypes have been suggested based on the antigens known to be present in certain tissues, specifically vascular and lymphatic tissue. Despite these seemingly distinct histologies, 6 lesions classified as vascular type displayed some histologic overlap with the lymphatic-type AVLs. The authors concluded that the vascular type showed greater potential to develop into an angiosarcoma based on the degree of endothelial atypia.1

In 2011, Santi et al13 found that both AVLs and angiosarcomas share inactivation mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, providing further evidence to suggest that AVLs may be precursors to angiosarcomas.

Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains questionable, research has shown that they do have a propensity to recur.3 In 2007, Gengler et al3 determined that 20% of patients with AVLs experienced recurrence after a biopsy or excision with varying margins; however, the group stated that these new vascular lesions might not be recurrences but rather entirely new lesions in the same irradiated field (field-effect phenomenon). Several other studies demonstrated that more than 30% of patients with 1 AVL developed more lesions within the same irradiated area.3,14-16 Despite the high rate of recurrence documented in the literature, only 5 of more than 100 diagnosed AVLs have progressed to angiosarcoma.1,3

Many differences can be noted when comparing the histology of AVLs versus angiosarcomas, though some are subtle (Table). Angiosarcomas display poorly circumscribed vascular infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, multilayering of endothelial cells, prominent nucleoli, hemorrhage, mitoses, and notable aytpia. Atypical vascular lesions lack these features and tend to be wedge shaped and display chronic inflammation.8,15,17-19 Atypical vascular lesions show superficial localized growth without destruction of adjacent adnexa, display dilated vascular spaces, and exhibit large endothelial cells.5,6,8,14,15,19,20 However, there is overlap between AVLs and angiosarcomas that can make diagnosis difficult.2,14,16,17,19 Areas within or just outside of an angiosarcoma, especially in well-differentiated angiosarcomas, can appear histologically identical to AVLs, and multiple biopsies may be required for diagnosis.17,19,21

Conclusion

More research is needed in the arenas of classification, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for AVLs. In particular, more specific histologic markers may be needed to identify those AVLs that may progress to angiosarcomas. Although most AVLs are treated with excision, a consensus needs to be reached on adequate surgical margins. Lastly, due to the tendency of AVLs to recur coupled with their unknown malignant potential, recommendations are needed for consistent follow-up examinations.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process; a study from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Hoda SA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas of the breast with atypical histological features: further analysis of histological subtypes confirming their benign character. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:553-560.

- Wagamon K, Ranchoff RE, Rosenberg AS, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:912-913.

- Diaz-Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin following radiotherapy: a report of five new cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1999;35:319-327.

- Martín-González T, Sanz-Trelles A, Del Boz J, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules and plaques after radiotherapy [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:84-86.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1047-1057.

- Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:164-167.

- Hildebrandt G, Mittag M, Gutz U, et al. Cutaneous breast angiosarcoma after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:580-583.

- Di Tommaso L, Fabbri A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising after radiotherapy treatment of a breast carcinoma: description of a case and review of the literature [in Italian]. Pathologica. 2003;95:196-202.

- Santi R, Cetica V, Franchi A, et al. Tumour suppressor gene TP53 mutations in atypical vascular lesions of breast skin following radiotherapy. Histopathology. 2011;58:455-466.

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Benign vascular proliferations in irradiated skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:328-337.

- Brodie C, Provenzano E. Vascular proliferations of the breast. Histopathology. 2008;52:30-44.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Postradiation vascular proliferations: an increasing problem. Histopathology. 2006;48:106-114.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Kardum-Skelin I, Jelić-Puskarić B, Pazur M, et al. A case report of breast angiosarcoma. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:645-648.

- Mattoch IW, Robbins JB, Kempson RL, et al. Post-radiotherapy vascular proliferations in mammary skin: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:126-133.

- Bodet D, Rodríguez-Cano L, Bartralot R, et al. Benign lymphangiomatous papules of the skin associated with ovarian fibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S41-S44.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

Practice Points

- Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) of the breast can appear an average of 5 years following radiation therapy.

- Although the malignant potential of AVLs remains debatable, excision generally is recommended, as lesions tend to recur.

Prednisone and Vardenafil Hydrochloride for Refractory Levamisole-Induced Vasculitis

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000.The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

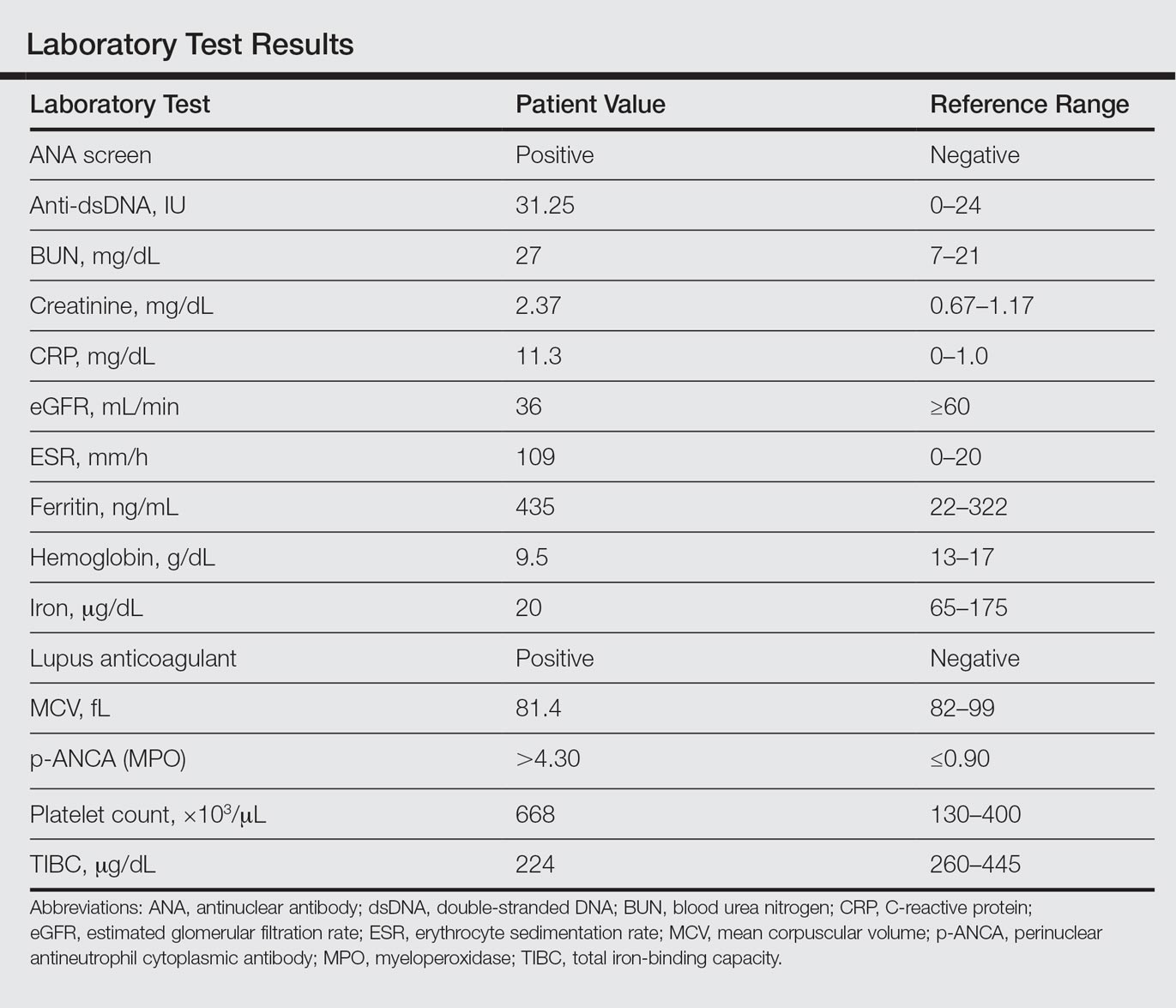

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

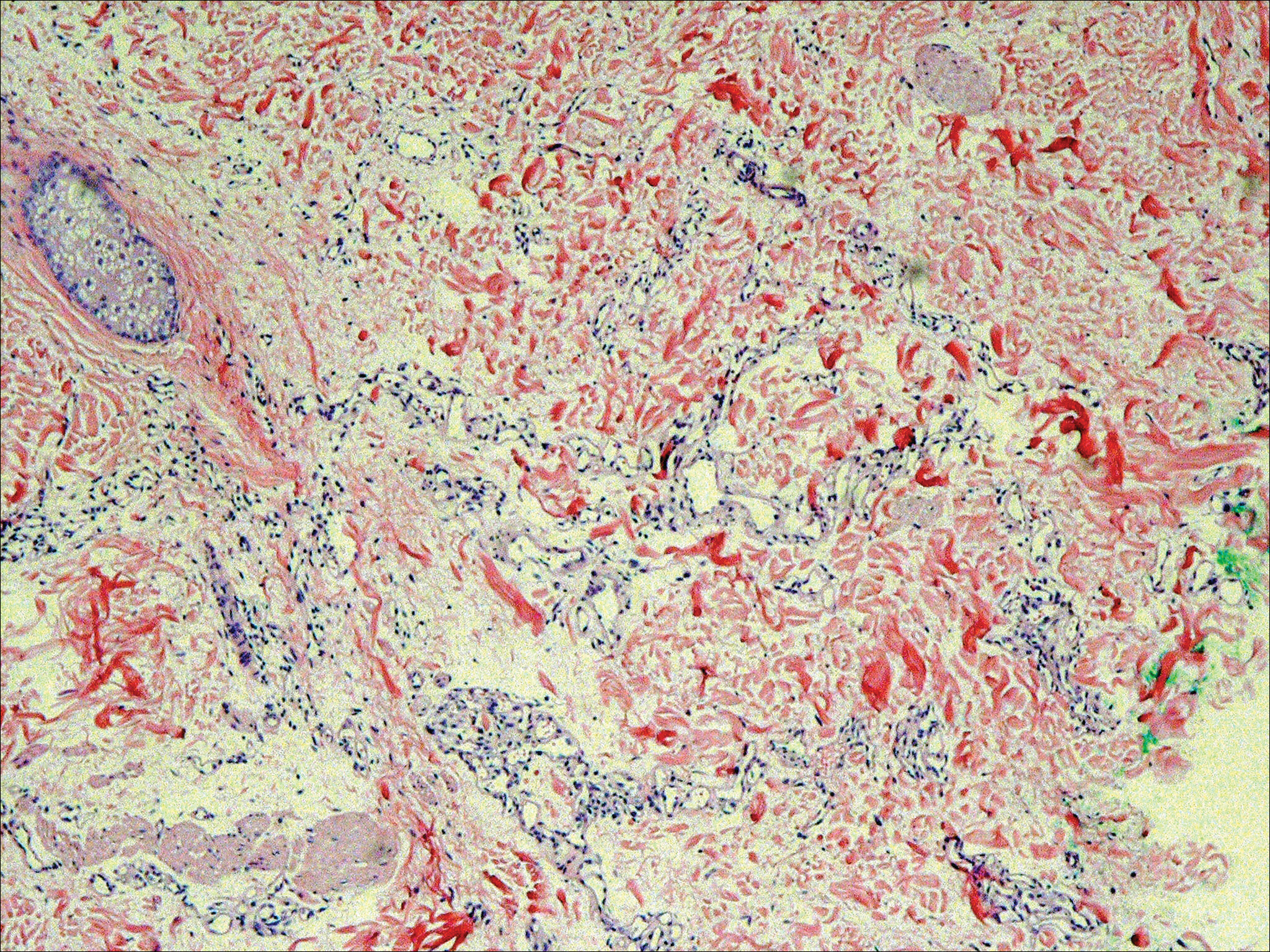

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh NMG, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole adultered cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

- Kahn TA, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR, et al. Vasculopathy, hematological, and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445-454.

- Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998-4001.

- Farmer RW, Malhotra PS, Mays MP, et al. Necrotizing peripheral vasculitis/vasculopathy following the use of cocaine laced with levamisole. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e6-e11.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ Jr. Levamisole-induced skin necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

- Buchanan JA, Vogel JA, Eberhardt AM. Levamisole-induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:83-84.

- Graff N, Whitworth K, Trigger C. Purpuric skin eruption in an illicit drug user: levamisole-induced vasculitis. Am J Emer Med. 2016;34:1321.

- Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Drug interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:88-95.

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000.The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000.The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh NMG, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole adultered cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

- Kahn TA, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR, et al. Vasculopathy, hematological, and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445-454.

- Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998-4001.

- Farmer RW, Malhotra PS, Mays MP, et al. Necrotizing peripheral vasculitis/vasculopathy following the use of cocaine laced with levamisole. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e6-e11.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ Jr. Levamisole-induced skin necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

- Buchanan JA, Vogel JA, Eberhardt AM. Levamisole-induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:83-84.

- Graff N, Whitworth K, Trigger C. Purpuric skin eruption in an illicit drug user: levamisole-induced vasculitis. Am J Emer Med. 2016;34:1321.

- Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Drug interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:88-95.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh NMG, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole adultered cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

- Kahn TA, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR, et al. Vasculopathy, hematological, and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445-454.

- Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998-4001.

- Farmer RW, Malhotra PS, Mays MP, et al. Necrotizing peripheral vasculitis/vasculopathy following the use of cocaine laced with levamisole. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e6-e11.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ Jr. Levamisole-induced skin necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

- Buchanan JA, Vogel JA, Eberhardt AM. Levamisole-induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:83-84.

- Graff N, Whitworth K, Trigger C. Purpuric skin eruption in an illicit drug user: levamisole-induced vasculitis. Am J Emer Med. 2016;34:1321.

- Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Drug interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:88-95.

Practice Points

- Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that, before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000, was previously used to treat various medical conditions.

- A majority of the cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole, which is added as an adulterant or bulking agent.

- Levamisole-cut cocaine is a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.

- Although treatment of levamisole toxicity is primarily supportive and includes cessation of levamisole-cut cocaine, a trial of prednisone and vardenafil hydrochloride can be considered for refractory levamisole-induced vasculopathy or for patients who continue to use the drug.

Onychomatricoma: A Rare Case of Unguioblastic Fibroma of the Fingernail Associated With Trauma

Onychomatricoma (OM) is a rare benign neoplasm of the nail matrix. Even less common is its possible association with both trauma to the nail apparatus and onychomycosis. This case illustrates both of these findings.

Case Report

A 72-year-old white man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 26-year history of a thickened nail plate on the right third finger that had developed soon after a baseball injury. The patient reported that the nail was completely normal prior to the trauma. According to the patient, the distal aspect of the finger was directly hit by a baseball and subsequently was wrapped by the patient for a few weeks. The nail then turned black and eventually fell off. When the nail grew back, it appeared abnormal and in its current state. The patient stated the lesion was asymptomatic at the time of presentation.

Physical examination revealed thickening, yellow discoloration, and transverse overcurvature of the nail plate on the right third finger with longitudinal ridging (Figure 1). A culture of the nail plate grew Chaetomium species. Application of topical clotrimazole for 3 months followed by a 6-week course of oral terbinafine produced no improvement. The patient then consented to a nail matrix incisional biopsy 6 months after initial presentation. After a digital nerve block was administered and a tourniquet of the proximal digit was applied, a nail avulsion was performed. Subsequently, a 3-mm punch biopsy was taken of the clinically apparent tumor in the nail matrix.