User login

Hyperkeratotic Nummular Plaques on the Upper Trunk

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

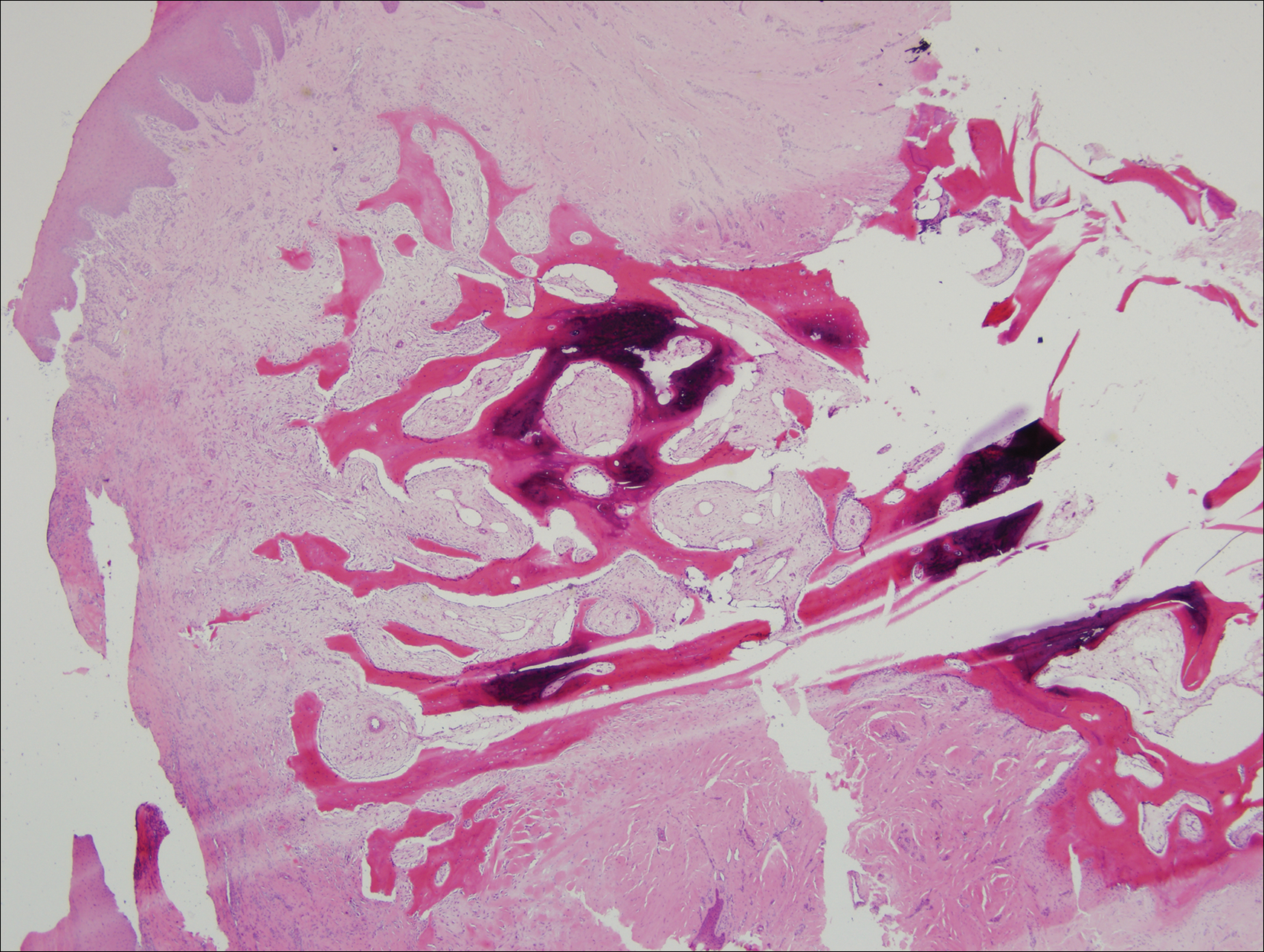

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

A 48-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis presented with papules and plaques on the upper trunk, proximal extremities, and volar wrists. Clear fluid–filled bullae occasionally developed within the plaques and subsequently ruptured and healed. Aside from intermittent lesion tenderness and irritation with the formation and rupture of the bullae, the patient’s plaques were asymptomatic, and she specifically denied pruritus. A review of systems revealed a history of genital irritation evaluated by a gynecologist; nystatin–triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied as needed provided relief. The patient denied any recent flares or any new or changing oral mucosa findings or symptoms, preceding medications, or family history of similar lesions. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, round, pink plaques with keratotic scale scattered across the upper trunk and central chest. The bilateral volar wrists were surfaced by well-circumscribed, thin, pink to violaceous, hyperkeratotic papules.

Subungual Exostosis

Case Report

A 41-year-old man with no dermatologic history presented for a skin examination. During a full-body skin examination, a lesion was identified on the right third toe that was partially visible underneath the nail plate. The patient stated that the lesion had been present for many years and did not appear to be growing but did cause occasional pain. On examination a 1-cm verrucous, hyperkeratotic, tan papule was noted at the distal end of the nail bed causing partial onycholysis (Figure 1). It was not tender to palpation.

A shave biopsy was obtained of the visible portion of the lesion, which revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and a population of dermal spindle cells in a myxoid stroma that could not be definitively identified. Special stains were nondiagnostic. The patient was referred to dermatologic surgery for rebiopsy of the lesion after removal of the nail plate. Mature bone was seen embedded in the dermis (Figure 2), and a diagnosis of subungual exostosis was made. Radiography of the digit confirmed a bony excrescence from the tuft of the toe, and the patient was referred to orthopedic surgery for definitive excision. There was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Subungual exostosis is an uncommon benign bone tumor located beneath or adjacent to the nail bed on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx.1 Although it can occur on any digit, 70% to 80% of cases have arisen on the distal phalanx of the hallux.2 Both sexes are equally susceptible. The majority of lesions occur during the second or third decades of life and usually are asymptomatic unless there is trauma or infection. Growth of the lesion over time can cause lifting or deformity of the nail plate and can cause slight discomfort while walking if located on the great toe.3 Common differential diagnoses include osteochondroma, wart, fibroma, paronychia, myositis ossificans, and pyogenic granuloma.3,4 Diagnosis can be confirmed with radiography, which should be performed prior to any biopsy or invasive procedure. In our patient, initial radiography could have obviated the need for 2 biopsies prior to definitive excision. Histopathologic evaluation typically reveals mature trabecular bone (Figure 2) surrounded by a fibrocartilage cap.

Subungual exostosis begins as an area of proliferating fibrous tissue with cartilaginous metaplasia located beneath or adjacent to the nail bed on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx.1 This cartilage undergoes enchondral ossification and is converted to trabecular bone. As the lesion grows and matures, the cartilaginous cap blends imperceptibly with the nail bed and comes into continuity with the underlying distal phalanx.1,3 This process continues until the lesion fuses completely with the distal phalanx.1 Although the cause of subungual exostosis has not been clearly established, chronic irritation, trauma, and chronic infections are considered causative factors of fibrocartilaginous metaplasia.4

The most commonly accepted treatment of subungual exostosis is a localized excision. Partial or total removal of the nail has traditionally be advocated to ensure complete excision of the exostosis, a nail-sparing technique that has been shown to enhance cosmetic results.3 Incomplete excision and incomplete maturation of the lesion have been reported to be responsible for almost 50% of recurrences.3 This high recurrence rate is due to difficulty in ensuring a total excision because the gradual merging of the fibrocartilage cap with the overlying nail bed makes it impossible to develop a cleavage plane5; as a result, it has been suggested that excision should only be attempted after maturation of the tumor so the cleavage plane can fully develop. Other studies claim that delaying treatment can result in elevation and deformity of the nail, pain, and secondary periungual infection.3

Conclusion

Subungual exostosis is a benign bony tumor of the distal phalanx that can cause pain and onycholysis. Radiography of the affected digit is a noninvasive way to confirm the diagnosis and should be part of the initial workup of any suspicious subungual tumor. Once identified, complete removal of the exostosis by excision has been shown to be an effective treatment with few complications.

- Letts M, Davidson D, Nizalik E. Subungual exostosis: diagnosis and treatment in children. J Trauma. 1998;44:346-349.

- Starnes A, Crosby K, Rowe DJ, et al. Subungual exostosis: a simple surgical technique. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:258-260.

- Lokiec F, Ezra E, Krasin E, et al. A simple and efficient surgical technique for subungual exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:76-79.

- Turan H, Uslu M, Erdem H. A case of subungual exostosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:186.

- Miller-Breslow A, Dorfman HD. Dupuytren’s (subungual) exostosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:368-378.

Case Report

A 41-year-old man with no dermatologic history presented for a skin examination. During a full-body skin examination, a lesion was identified on the right third toe that was partially visible underneath the nail plate. The patient stated that the lesion had been present for many years and did not appear to be growing but did cause occasional pain. On examination a 1-cm verrucous, hyperkeratotic, tan papule was noted at the distal end of the nail bed causing partial onycholysis (Figure 1). It was not tender to palpation.

A shave biopsy was obtained of the visible portion of the lesion, which revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and a population of dermal spindle cells in a myxoid stroma that could not be definitively identified. Special stains were nondiagnostic. The patient was referred to dermatologic surgery for rebiopsy of the lesion after removal of the nail plate. Mature bone was seen embedded in the dermis (Figure 2), and a diagnosis of subungual exostosis was made. Radiography of the digit confirmed a bony excrescence from the tuft of the toe, and the patient was referred to orthopedic surgery for definitive excision. There was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Subungual exostosis is an uncommon benign bone tumor located beneath or adjacent to the nail bed on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx.1 Although it can occur on any digit, 70% to 80% of cases have arisen on the distal phalanx of the hallux.2 Both sexes are equally susceptible. The majority of lesions occur during the second or third decades of life and usually are asymptomatic unless there is trauma or infection. Growth of the lesion over time can cause lifting or deformity of the nail plate and can cause slight discomfort while walking if located on the great toe.3 Common differential diagnoses include osteochondroma, wart, fibroma, paronychia, myositis ossificans, and pyogenic granuloma.3,4 Diagnosis can be confirmed with radiography, which should be performed prior to any biopsy or invasive procedure. In our patient, initial radiography could have obviated the need for 2 biopsies prior to definitive excision. Histopathologic evaluation typically reveals mature trabecular bone (Figure 2) surrounded by a fibrocartilage cap.

Subungual exostosis begins as an area of proliferating fibrous tissue with cartilaginous metaplasia located beneath or adjacent to the nail bed on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx.1 This cartilage undergoes enchondral ossification and is converted to trabecular bone. As the lesion grows and matures, the cartilaginous cap blends imperceptibly with the nail bed and comes into continuity with the underlying distal phalanx.1,3 This process continues until the lesion fuses completely with the distal phalanx.1 Although the cause of subungual exostosis has not been clearly established, chronic irritation, trauma, and chronic infections are considered causative factors of fibrocartilaginous metaplasia.4

The most commonly accepted treatment of subungual exostosis is a localized excision. Partial or total removal of the nail has traditionally be advocated to ensure complete excision of the exostosis, a nail-sparing technique that has been shown to enhance cosmetic results.3 Incomplete excision and incomplete maturation of the lesion have been reported to be responsible for almost 50% of recurrences.3 This high recurrence rate is due to difficulty in ensuring a total excision because the gradual merging of the fibrocartilage cap with the overlying nail bed makes it impossible to develop a cleavage plane5; as a result, it has been suggested that excision should only be attempted after maturation of the tumor so the cleavage plane can fully develop. Other studies claim that delaying treatment can result in elevation and deformity of the nail, pain, and secondary periungual infection.3

Conclusion

Subungual exostosis is a benign bony tumor of the distal phalanx that can cause pain and onycholysis. Radiography of the affected digit is a noninvasive way to confirm the diagnosis and should be part of the initial workup of any suspicious subungual tumor. Once identified, complete removal of the exostosis by excision has been shown to be an effective treatment with few complications.

Case Report

A 41-year-old man with no dermatologic history presented for a skin examination. During a full-body skin examination, a lesion was identified on the right third toe that was partially visible underneath the nail plate. The patient stated that the lesion had been present for many years and did not appear to be growing but did cause occasional pain. On examination a 1-cm verrucous, hyperkeratotic, tan papule was noted at the distal end of the nail bed causing partial onycholysis (Figure 1). It was not tender to palpation.

A shave biopsy was obtained of the visible portion of the lesion, which revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and a population of dermal spindle cells in a myxoid stroma that could not be definitively identified. Special stains were nondiagnostic. The patient was referred to dermatologic surgery for rebiopsy of the lesion after removal of the nail plate. Mature bone was seen embedded in the dermis (Figure 2), and a diagnosis of subungual exostosis was made. Radiography of the digit confirmed a bony excrescence from the tuft of the toe, and the patient was referred to orthopedic surgery for definitive excision. There was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Subungual exostosis is an uncommon benign bone tumor located beneath or adjacent to the nail bed on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx.1 Although it can occur on any digit, 70% to 80% of cases have arisen on the distal phalanx of the hallux.2 Both sexes are equally susceptible. The majority of lesions occur during the second or third decades of life and usually are asymptomatic unless there is trauma or infection. Growth of the lesion over time can cause lifting or deformity of the nail plate and can cause slight discomfort while walking if located on the great toe.3 Common differential diagnoses include osteochondroma, wart, fibroma, paronychia, myositis ossificans, and pyogenic granuloma.3,4 Diagnosis can be confirmed with radiography, which should be performed prior to any biopsy or invasive procedure. In our patient, initial radiography could have obviated the need for 2 biopsies prior to definitive excision. Histopathologic evaluation typically reveals mature trabecular bone (Figure 2) surrounded by a fibrocartilage cap.

Subungual exostosis begins as an area of proliferating fibrous tissue with cartilaginous metaplasia located beneath or adjacent to the nail bed on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx.1 This cartilage undergoes enchondral ossification and is converted to trabecular bone. As the lesion grows and matures, the cartilaginous cap blends imperceptibly with the nail bed and comes into continuity with the underlying distal phalanx.1,3 This process continues until the lesion fuses completely with the distal phalanx.1 Although the cause of subungual exostosis has not been clearly established, chronic irritation, trauma, and chronic infections are considered causative factors of fibrocartilaginous metaplasia.4

The most commonly accepted treatment of subungual exostosis is a localized excision. Partial or total removal of the nail has traditionally be advocated to ensure complete excision of the exostosis, a nail-sparing technique that has been shown to enhance cosmetic results.3 Incomplete excision and incomplete maturation of the lesion have been reported to be responsible for almost 50% of recurrences.3 This high recurrence rate is due to difficulty in ensuring a total excision because the gradual merging of the fibrocartilage cap with the overlying nail bed makes it impossible to develop a cleavage plane5; as a result, it has been suggested that excision should only be attempted after maturation of the tumor so the cleavage plane can fully develop. Other studies claim that delaying treatment can result in elevation and deformity of the nail, pain, and secondary periungual infection.3

Conclusion

Subungual exostosis is a benign bony tumor of the distal phalanx that can cause pain and onycholysis. Radiography of the affected digit is a noninvasive way to confirm the diagnosis and should be part of the initial workup of any suspicious subungual tumor. Once identified, complete removal of the exostosis by excision has been shown to be an effective treatment with few complications.

- Letts M, Davidson D, Nizalik E. Subungual exostosis: diagnosis and treatment in children. J Trauma. 1998;44:346-349.

- Starnes A, Crosby K, Rowe DJ, et al. Subungual exostosis: a simple surgical technique. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:258-260.

- Lokiec F, Ezra E, Krasin E, et al. A simple and efficient surgical technique for subungual exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:76-79.

- Turan H, Uslu M, Erdem H. A case of subungual exostosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:186.

- Miller-Breslow A, Dorfman HD. Dupuytren’s (subungual) exostosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:368-378.

- Letts M, Davidson D, Nizalik E. Subungual exostosis: diagnosis and treatment in children. J Trauma. 1998;44:346-349.

- Starnes A, Crosby K, Rowe DJ, et al. Subungual exostosis: a simple surgical technique. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:258-260.

- Lokiec F, Ezra E, Krasin E, et al. A simple and efficient surgical technique for subungual exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:76-79.

- Turan H, Uslu M, Erdem H. A case of subungual exostosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:186.

- Miller-Breslow A, Dorfman HD. Dupuytren’s (subungual) exostosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:368-378.

Practice Points

- Subungual exostosis is a benign tumor that is most common on the hallux.

- Plain radiographs can identify an exostosis and should be part of the initial workup of any subungual tumor.

- Surgical excision is an effective and well-tolerated treatment of subungual exostosis.