User login

Fungal Osler Nodes Indicate Candidal Infective Endocarditis

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old woman presented with a low-grade fever (temperature, 38.0 °C) and painful acral lesions of 1 week’s duration. She had a history of hepatitis C viral infection and intravenous (IV) drug use, as well as polymicrobial infective endocarditis that involved the tricuspid and aortic valves; pathogenic organisms were identified via blood culture as Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia species, Streptococcus viridans, and Candida albicans. The patient had received a mechanical aortic valve and bioprosthetic tricuspid valve replacement 5 months prior with warfarin therapy and had completed a postsurgical 6-week course of high-dose micafungin. She reported that she had developed painful, violaceous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the left foot 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her symptoms improved with a short systemic steroid taper; however, within a week she developed new tender, erythematous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the right foot and the palmar surface of the left hand with associated lower extremity swelling. She denied other symptoms, including fever, chills, neurologic symptoms, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, and hematochezia. Due to worsening cutaneous findings, the patient presented to the emergency department, prompting hospital admission for empiric antibacterial therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam for suspected infectious endocarditis. Dermatology was consulted after 1 day of antibacterial therapy without improvement to determine the etiology of the patient’s skin findings.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile with partially blanching violaceous to purpuric, tender, edematous papules on the left fourth and fifth finger pads, as well as scattered, painful, purpuric patches with stellate borders on the right plantar foot (Figure 1). Laboratory test results revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin, 11.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–15.0 g/dL], mild neutrophilia (neutrophils, 8.4×109/L [reference range, 1.9–7.9×109/L], elevated acute-phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 71 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 5.7 mg/dL [reference range, 0.0–0.5 mg/dL]), and positive hepatitis C virus antibody with an undetectable viral load. At the time of dermatologic evaluation, admission blood cultures and transthoracic echocardiogram were negative. Additionally, a transesophageal echocardiogram, limited by artifact from the mechanical aortic valve, was equivocal for valvular pathology. Subsequent ophthalmologic evaluation was negative for lesions associated with endocarditis, such as retinal hemorrhages.

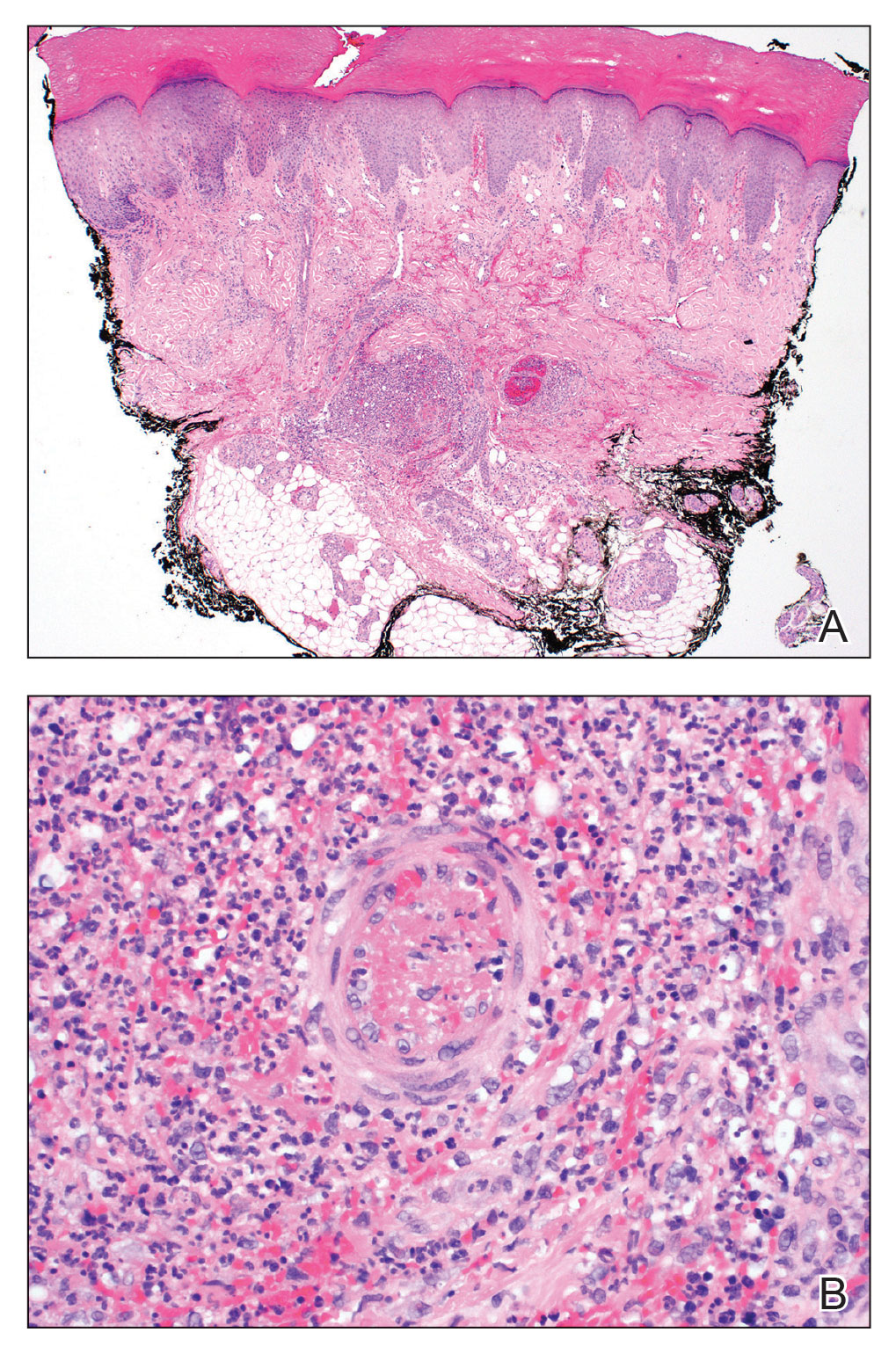

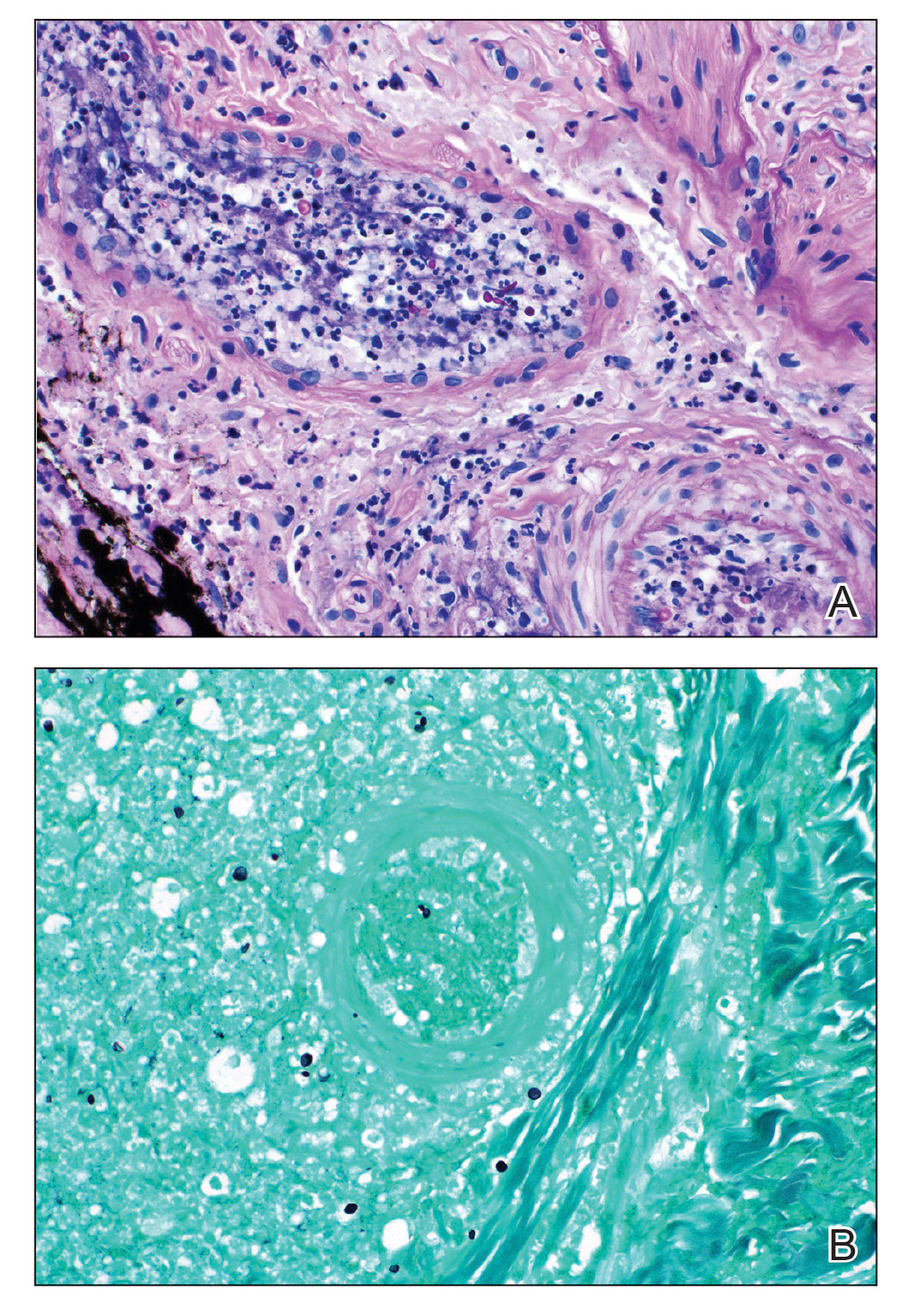

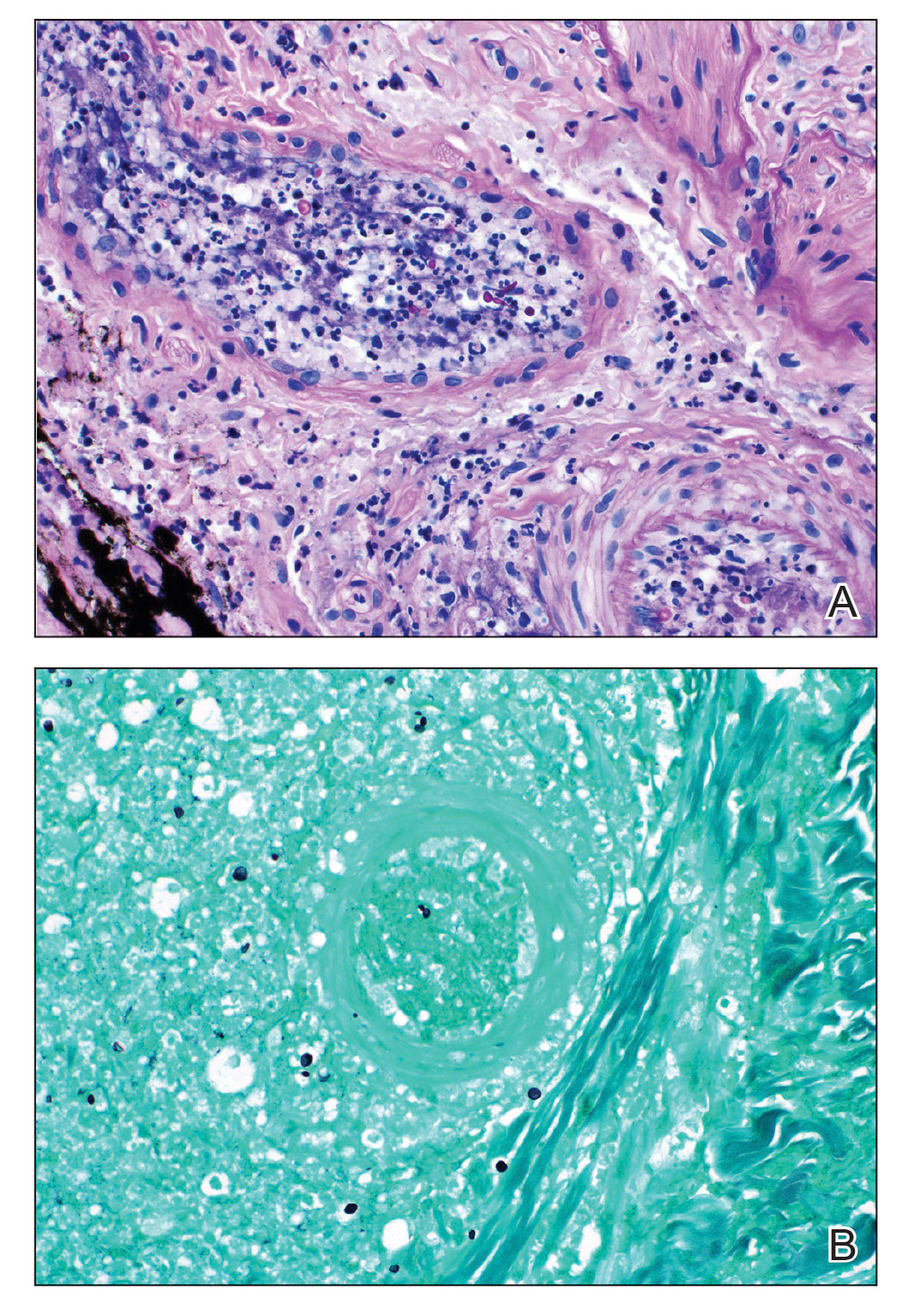

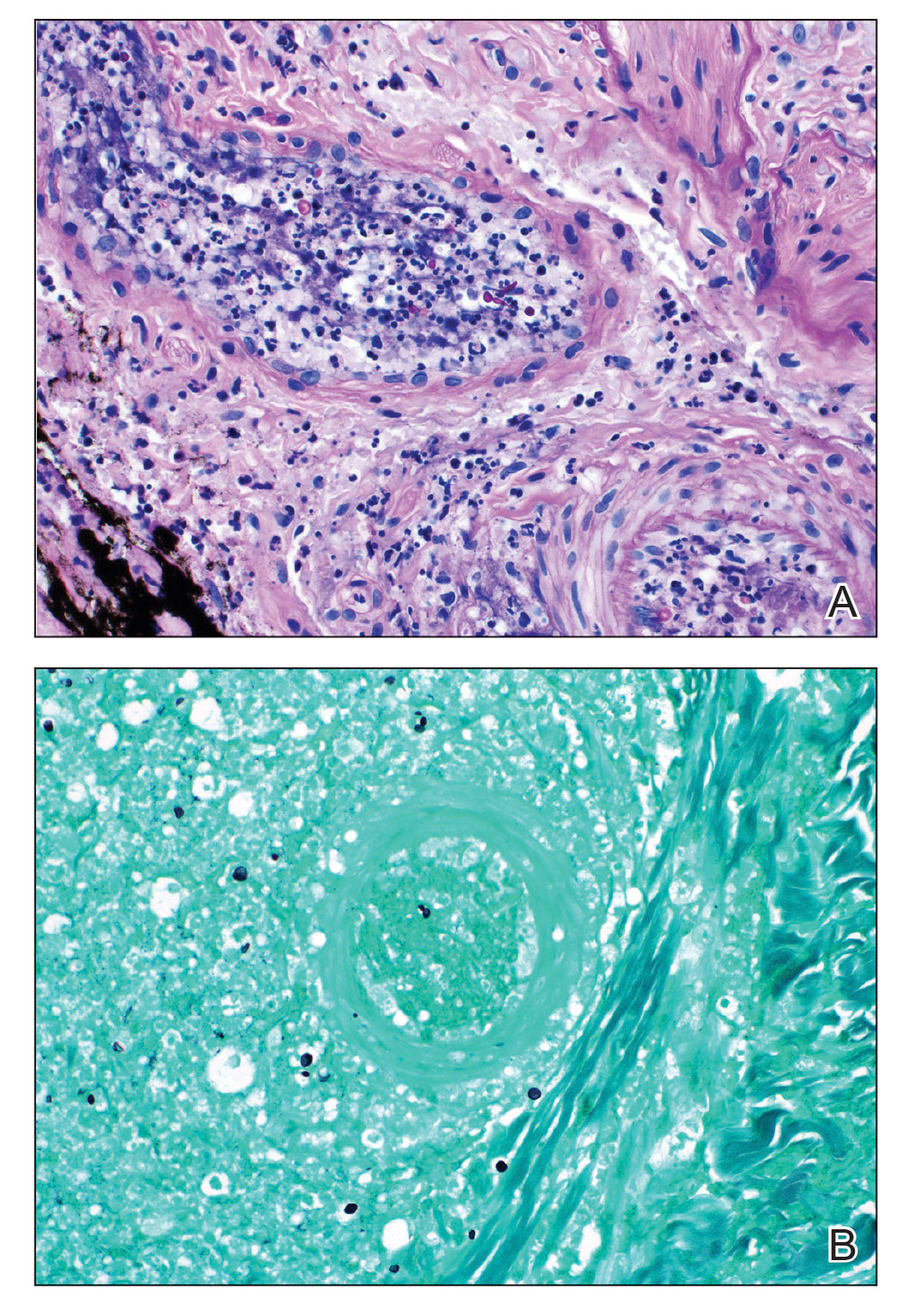

Punch biopsies of the left fourth finger pad were submitted for histopathologic analysis and tissue cultures. Histopathology demonstrated deep dermal perivascular neutrophilic inflammation with multiple intravascular thrombi, perivascular fibrin, and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains revealed fungal spores with rare pseudohyphae within the thrombosed vascular spaces and the perivascular dermis, consistent with fungal septic emboli (Figure 3).

Empiric systemic antifungal coverage composed of IV liposomal amphotericin B and oral flucytosine was initiated, and the patient’s tender acral papules rapidly improved. Within 48 hours of biopsy, skin tissue culture confirmed the presence of C albicans. Four days after the preliminary dermatopathology report, confirmatory blood cultures resulted with pansensitive C albicans. Final tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacteria including mycobacteria. In addition to a 6-week course of IV amphotericin B and flucytosine, repeat surgical intervention was considered, and lifelong suppressive antifungal oral therapy was recommended. Unfortunately, the patient did not present for follow-up. Three months later, she presented to the emergency department with peritonitis; in the operating room, she was found to have ischemia of the entirety of the small and large intestines and died shortly thereafter.

Fungal endocarditis is rare, tending to develop in patient populations with particular risk factors such as immune compromise, structural heart defects or prosthetic valves, and IV drug use. Candida infective endocarditis (CIE) represents less than 2% of infective endocarditis cases and carries a high mortality rate (30%–80%).1-3 Diagnosis may be challenging, as the clinical presentation varies widely. Although some patients may present with classic features of infective endocarditis, including fever, cardiac murmurs, and positive blood cultures, many cases of infective endocarditis present with nonspecific symptoms, raising a broad clinical differential diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis, which is seen in 82% of patients with fungal endocarditis, may be attributed to the slow progression of symptoms, inconclusive cardiac imaging, or negative blood cultures seen in almost one-third of cases.2,3 The feared complication of systemic embolization via infective endocarditis may occur in up to one-half of cases, with the highest rates associated with staphylococcal or fungal pathogens.2 The risk for embolization in fungal endocarditis is independent of the size of the cardiac valve vegetations; accordingly, sequelae of embolic complications may arise despite negative cardiac imaging.4 Embolic complications, which typically are seen within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment, may serve as the presenting feature of endocarditis and may even occur after completion of antimicrobial therapy.

Detection of cutaneous manifestations of infective endocarditis, including Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and splinter hemorrhages, may allow for earlier diagnosis. Despite eponymous recognition, Janeway lesions and Osler nodes are relatively uncommon manifestations of infective endocarditis and may be found in only 5% to 15% of cases.5 Biopsies of suspected Janeway lesions and Osler nodes may allow for recognition of relevant vascular pathology, identification of the causative pathogen, and strong support for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.4-7

The initial photomicrograph of corresponding Janeway lesion histopathology was published by Kerr in 1955 and revealed dermal microabscesses posited to be secondary to bacterial emboli.8,9 Additional cases through the years have reported overlapping histopathologic features of Janeway lesions and Osler nodes, with the latter often defined by the presence of vasculitis.4 Although there appears to be ongoing debate and overlap between the 2 integumentary findings, a general consensus on differentiation takes into account both the clinical signs and symptoms as well as the histopathologic findings.10,11

Osler nodes present as tender, violaceous, subcutaneous nodules on the acral surfaces, usually on the pads of the fingers and toes.5 The pathogenesis involves the deposition of immune complexes as a sequela of vascular occlusion by microthrombi classically seen in the late phase of subacute endocarditis. Janeway lesions present as nontender erythematous macules on the acral surfaces and are thought to represent microthrombi with dermal microabscesses, more common in acute endocarditis. Our patient demonstrated features of both Osler nodes and Janeway lesions. Despite the presence of fungal thrombi—a pathophysiology closer to that of Janeway lesions—the clinical presentation of painful acral nodules affecting finger pads and histologic features of vasculitis may be better characterized as Osler nodes. Regardless of pathogenesis, these cutaneous findings serve as a minor clinical criterion in the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis when present.12

Candida infective endocarditis should be suspected in a patient with a history of valvular disease or prior infective endocarditis with fungemia, unexplained neurologic signs, or manifestations of peripheral embolization despite negative blood cultures.3 Particularly in the setting of negative cardiac imaging, recognition of CIE requires heightened diagnostic acumen and clinicopathologic correlation. Although culture and pathologic examination of valvular vegetations represents the gold standard for diagnosis of CIE, aspiration and culture of easily accessible septic emboli may provide rapid identification of the etiologic pathogen. In 1976, Alpert et al13 identified C albicans from an aspirated Osler node. Postmortem examination revealed extensive involvement of the homograft valve and aortic root with C albicans.13 Many other examples exist in the literature demonstrating matching pathogenic isolates from microbiologic cultures of skin and blood.4,9,14,15 Thadepalli and Francis7 investigated 26 cases of endocarditis in heroin users in which the admitting diagnosis was endocarditis in only 4 cases. The etiologic pathogen was aspirated from secondary sites of localized infections secondary to emboli, including cutaneous lesions in 10 of the cases. Gram stain and culture revealed the causative organism leading to the ultimate diagnosis and management in 17 of 26 patients with endocarditis.7

The incidence of fungal endocarditis is increasing, with a reported 67% of cases caused by nosocomial infection.1 Given the rising incidence of fungal endocarditis and its accompanying diagnostic difficulties, including frequently negative blood cultures and cardiac imaging, clinicians must perform careful skin examinations, employ judicious use of skin biopsy, and carefully correlate clinical and pathologic findings to improve recognition of this disease and guide patient care.

- Arnold CJ, Johnson M, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: an observational cohort study with a focus on therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2365. doi:10.1128/AAC.04867-14

- Chaudhary SC, Sawlani KK, Arora R, et al. Native aortic valve fungal endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012007144. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007144

- Ellis ME, Al-Abdely H, Sandridge A, et al. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:50-62. doi:10.1086/317550

- Gil MP, Velasco M, Botella R, et al. Janeway lesions: differential diagnosis with Osler’s nodes. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:673-674. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb04025.x

- Gomes RT, Tiberto LR, Bello VNM, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of infective endocarditis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:92-94.

- Yee JM. Osler’s nodes and the recognition of infective endocarditis: a lesion of diagnostic importance. South Med J. 1987;80:753-757.

- Thadepalli H, Francis C. Diagnostic clues in metastatic lesions of endocarditia in addicts. West J Med. 1978;128:1-5.

- Kerr A Jr. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis. Charles C. Thomas; 1955.

- Kerr A Jr, Tan JS. Biopsies of the Janeway lesion of infective endocarditis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:124-129. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01113.x

- Marrie TJ. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Am J Med. 2008;121:105-106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.035

- Gunson TH, Oliver GF. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:251-255. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00397.x

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK, et al. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Am J Med. 1994;96:200-209.

- Alpert JS, Krous HF, Dalen JE, et al. Pathogenesis of Osler’s nodes. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:471-473. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-85-4-471

- Cardullo AC, Silvers DN, Grossman ME. Janeway lesions and Osler’s nodes: a review of histopathologic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1088-1090. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70157-D

- Vinson RP, Chung A, Elston DM, et al. Septic microemboli in a Janeway lesion of bacterial endocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:984-985. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90125-5

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old woman presented with a low-grade fever (temperature, 38.0 °C) and painful acral lesions of 1 week’s duration. She had a history of hepatitis C viral infection and intravenous (IV) drug use, as well as polymicrobial infective endocarditis that involved the tricuspid and aortic valves; pathogenic organisms were identified via blood culture as Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia species, Streptococcus viridans, and Candida albicans. The patient had received a mechanical aortic valve and bioprosthetic tricuspid valve replacement 5 months prior with warfarin therapy and had completed a postsurgical 6-week course of high-dose micafungin. She reported that she had developed painful, violaceous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the left foot 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her symptoms improved with a short systemic steroid taper; however, within a week she developed new tender, erythematous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the right foot and the palmar surface of the left hand with associated lower extremity swelling. She denied other symptoms, including fever, chills, neurologic symptoms, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, and hematochezia. Due to worsening cutaneous findings, the patient presented to the emergency department, prompting hospital admission for empiric antibacterial therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam for suspected infectious endocarditis. Dermatology was consulted after 1 day of antibacterial therapy without improvement to determine the etiology of the patient’s skin findings.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile with partially blanching violaceous to purpuric, tender, edematous papules on the left fourth and fifth finger pads, as well as scattered, painful, purpuric patches with stellate borders on the right plantar foot (Figure 1). Laboratory test results revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin, 11.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–15.0 g/dL], mild neutrophilia (neutrophils, 8.4×109/L [reference range, 1.9–7.9×109/L], elevated acute-phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 71 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 5.7 mg/dL [reference range, 0.0–0.5 mg/dL]), and positive hepatitis C virus antibody with an undetectable viral load. At the time of dermatologic evaluation, admission blood cultures and transthoracic echocardiogram were negative. Additionally, a transesophageal echocardiogram, limited by artifact from the mechanical aortic valve, was equivocal for valvular pathology. Subsequent ophthalmologic evaluation was negative for lesions associated with endocarditis, such as retinal hemorrhages.

Punch biopsies of the left fourth finger pad were submitted for histopathologic analysis and tissue cultures. Histopathology demonstrated deep dermal perivascular neutrophilic inflammation with multiple intravascular thrombi, perivascular fibrin, and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains revealed fungal spores with rare pseudohyphae within the thrombosed vascular spaces and the perivascular dermis, consistent with fungal septic emboli (Figure 3).

Empiric systemic antifungal coverage composed of IV liposomal amphotericin B and oral flucytosine was initiated, and the patient’s tender acral papules rapidly improved. Within 48 hours of biopsy, skin tissue culture confirmed the presence of C albicans. Four days after the preliminary dermatopathology report, confirmatory blood cultures resulted with pansensitive C albicans. Final tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacteria including mycobacteria. In addition to a 6-week course of IV amphotericin B and flucytosine, repeat surgical intervention was considered, and lifelong suppressive antifungal oral therapy was recommended. Unfortunately, the patient did not present for follow-up. Three months later, she presented to the emergency department with peritonitis; in the operating room, she was found to have ischemia of the entirety of the small and large intestines and died shortly thereafter.

Fungal endocarditis is rare, tending to develop in patient populations with particular risk factors such as immune compromise, structural heart defects or prosthetic valves, and IV drug use. Candida infective endocarditis (CIE) represents less than 2% of infective endocarditis cases and carries a high mortality rate (30%–80%).1-3 Diagnosis may be challenging, as the clinical presentation varies widely. Although some patients may present with classic features of infective endocarditis, including fever, cardiac murmurs, and positive blood cultures, many cases of infective endocarditis present with nonspecific symptoms, raising a broad clinical differential diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis, which is seen in 82% of patients with fungal endocarditis, may be attributed to the slow progression of symptoms, inconclusive cardiac imaging, or negative blood cultures seen in almost one-third of cases.2,3 The feared complication of systemic embolization via infective endocarditis may occur in up to one-half of cases, with the highest rates associated with staphylococcal or fungal pathogens.2 The risk for embolization in fungal endocarditis is independent of the size of the cardiac valve vegetations; accordingly, sequelae of embolic complications may arise despite negative cardiac imaging.4 Embolic complications, which typically are seen within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment, may serve as the presenting feature of endocarditis and may even occur after completion of antimicrobial therapy.

Detection of cutaneous manifestations of infective endocarditis, including Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and splinter hemorrhages, may allow for earlier diagnosis. Despite eponymous recognition, Janeway lesions and Osler nodes are relatively uncommon manifestations of infective endocarditis and may be found in only 5% to 15% of cases.5 Biopsies of suspected Janeway lesions and Osler nodes may allow for recognition of relevant vascular pathology, identification of the causative pathogen, and strong support for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.4-7

The initial photomicrograph of corresponding Janeway lesion histopathology was published by Kerr in 1955 and revealed dermal microabscesses posited to be secondary to bacterial emboli.8,9 Additional cases through the years have reported overlapping histopathologic features of Janeway lesions and Osler nodes, with the latter often defined by the presence of vasculitis.4 Although there appears to be ongoing debate and overlap between the 2 integumentary findings, a general consensus on differentiation takes into account both the clinical signs and symptoms as well as the histopathologic findings.10,11

Osler nodes present as tender, violaceous, subcutaneous nodules on the acral surfaces, usually on the pads of the fingers and toes.5 The pathogenesis involves the deposition of immune complexes as a sequela of vascular occlusion by microthrombi classically seen in the late phase of subacute endocarditis. Janeway lesions present as nontender erythematous macules on the acral surfaces and are thought to represent microthrombi with dermal microabscesses, more common in acute endocarditis. Our patient demonstrated features of both Osler nodes and Janeway lesions. Despite the presence of fungal thrombi—a pathophysiology closer to that of Janeway lesions—the clinical presentation of painful acral nodules affecting finger pads and histologic features of vasculitis may be better characterized as Osler nodes. Regardless of pathogenesis, these cutaneous findings serve as a minor clinical criterion in the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis when present.12

Candida infective endocarditis should be suspected in a patient with a history of valvular disease or prior infective endocarditis with fungemia, unexplained neurologic signs, or manifestations of peripheral embolization despite negative blood cultures.3 Particularly in the setting of negative cardiac imaging, recognition of CIE requires heightened diagnostic acumen and clinicopathologic correlation. Although culture and pathologic examination of valvular vegetations represents the gold standard for diagnosis of CIE, aspiration and culture of easily accessible septic emboli may provide rapid identification of the etiologic pathogen. In 1976, Alpert et al13 identified C albicans from an aspirated Osler node. Postmortem examination revealed extensive involvement of the homograft valve and aortic root with C albicans.13 Many other examples exist in the literature demonstrating matching pathogenic isolates from microbiologic cultures of skin and blood.4,9,14,15 Thadepalli and Francis7 investigated 26 cases of endocarditis in heroin users in which the admitting diagnosis was endocarditis in only 4 cases. The etiologic pathogen was aspirated from secondary sites of localized infections secondary to emboli, including cutaneous lesions in 10 of the cases. Gram stain and culture revealed the causative organism leading to the ultimate diagnosis and management in 17 of 26 patients with endocarditis.7

The incidence of fungal endocarditis is increasing, with a reported 67% of cases caused by nosocomial infection.1 Given the rising incidence of fungal endocarditis and its accompanying diagnostic difficulties, including frequently negative blood cultures and cardiac imaging, clinicians must perform careful skin examinations, employ judicious use of skin biopsy, and carefully correlate clinical and pathologic findings to improve recognition of this disease and guide patient care.

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old woman presented with a low-grade fever (temperature, 38.0 °C) and painful acral lesions of 1 week’s duration. She had a history of hepatitis C viral infection and intravenous (IV) drug use, as well as polymicrobial infective endocarditis that involved the tricuspid and aortic valves; pathogenic organisms were identified via blood culture as Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia species, Streptococcus viridans, and Candida albicans. The patient had received a mechanical aortic valve and bioprosthetic tricuspid valve replacement 5 months prior with warfarin therapy and had completed a postsurgical 6-week course of high-dose micafungin. She reported that she had developed painful, violaceous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the left foot 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her symptoms improved with a short systemic steroid taper; however, within a week she developed new tender, erythematous, thin papules on the plantar surface of the right foot and the palmar surface of the left hand with associated lower extremity swelling. She denied other symptoms, including fever, chills, neurologic symptoms, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, and hematochezia. Due to worsening cutaneous findings, the patient presented to the emergency department, prompting hospital admission for empiric antibacterial therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam for suspected infectious endocarditis. Dermatology was consulted after 1 day of antibacterial therapy without improvement to determine the etiology of the patient’s skin findings.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile with partially blanching violaceous to purpuric, tender, edematous papules on the left fourth and fifth finger pads, as well as scattered, painful, purpuric patches with stellate borders on the right plantar foot (Figure 1). Laboratory test results revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin, 11.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–15.0 g/dL], mild neutrophilia (neutrophils, 8.4×109/L [reference range, 1.9–7.9×109/L], elevated acute-phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 71 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 5.7 mg/dL [reference range, 0.0–0.5 mg/dL]), and positive hepatitis C virus antibody with an undetectable viral load. At the time of dermatologic evaluation, admission blood cultures and transthoracic echocardiogram were negative. Additionally, a transesophageal echocardiogram, limited by artifact from the mechanical aortic valve, was equivocal for valvular pathology. Subsequent ophthalmologic evaluation was negative for lesions associated with endocarditis, such as retinal hemorrhages.

Punch biopsies of the left fourth finger pad were submitted for histopathologic analysis and tissue cultures. Histopathology demonstrated deep dermal perivascular neutrophilic inflammation with multiple intravascular thrombi, perivascular fibrin, and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains revealed fungal spores with rare pseudohyphae within the thrombosed vascular spaces and the perivascular dermis, consistent with fungal septic emboli (Figure 3).

Empiric systemic antifungal coverage composed of IV liposomal amphotericin B and oral flucytosine was initiated, and the patient’s tender acral papules rapidly improved. Within 48 hours of biopsy, skin tissue culture confirmed the presence of C albicans. Four days after the preliminary dermatopathology report, confirmatory blood cultures resulted with pansensitive C albicans. Final tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacteria including mycobacteria. In addition to a 6-week course of IV amphotericin B and flucytosine, repeat surgical intervention was considered, and lifelong suppressive antifungal oral therapy was recommended. Unfortunately, the patient did not present for follow-up. Three months later, she presented to the emergency department with peritonitis; in the operating room, she was found to have ischemia of the entirety of the small and large intestines and died shortly thereafter.

Fungal endocarditis is rare, tending to develop in patient populations with particular risk factors such as immune compromise, structural heart defects or prosthetic valves, and IV drug use. Candida infective endocarditis (CIE) represents less than 2% of infective endocarditis cases and carries a high mortality rate (30%–80%).1-3 Diagnosis may be challenging, as the clinical presentation varies widely. Although some patients may present with classic features of infective endocarditis, including fever, cardiac murmurs, and positive blood cultures, many cases of infective endocarditis present with nonspecific symptoms, raising a broad clinical differential diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis, which is seen in 82% of patients with fungal endocarditis, may be attributed to the slow progression of symptoms, inconclusive cardiac imaging, or negative blood cultures seen in almost one-third of cases.2,3 The feared complication of systemic embolization via infective endocarditis may occur in up to one-half of cases, with the highest rates associated with staphylococcal or fungal pathogens.2 The risk for embolization in fungal endocarditis is independent of the size of the cardiac valve vegetations; accordingly, sequelae of embolic complications may arise despite negative cardiac imaging.4 Embolic complications, which typically are seen within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment, may serve as the presenting feature of endocarditis and may even occur after completion of antimicrobial therapy.

Detection of cutaneous manifestations of infective endocarditis, including Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and splinter hemorrhages, may allow for earlier diagnosis. Despite eponymous recognition, Janeway lesions and Osler nodes are relatively uncommon manifestations of infective endocarditis and may be found in only 5% to 15% of cases.5 Biopsies of suspected Janeway lesions and Osler nodes may allow for recognition of relevant vascular pathology, identification of the causative pathogen, and strong support for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.4-7

The initial photomicrograph of corresponding Janeway lesion histopathology was published by Kerr in 1955 and revealed dermal microabscesses posited to be secondary to bacterial emboli.8,9 Additional cases through the years have reported overlapping histopathologic features of Janeway lesions and Osler nodes, with the latter often defined by the presence of vasculitis.4 Although there appears to be ongoing debate and overlap between the 2 integumentary findings, a general consensus on differentiation takes into account both the clinical signs and symptoms as well as the histopathologic findings.10,11

Osler nodes present as tender, violaceous, subcutaneous nodules on the acral surfaces, usually on the pads of the fingers and toes.5 The pathogenesis involves the deposition of immune complexes as a sequela of vascular occlusion by microthrombi classically seen in the late phase of subacute endocarditis. Janeway lesions present as nontender erythematous macules on the acral surfaces and are thought to represent microthrombi with dermal microabscesses, more common in acute endocarditis. Our patient demonstrated features of both Osler nodes and Janeway lesions. Despite the presence of fungal thrombi—a pathophysiology closer to that of Janeway lesions—the clinical presentation of painful acral nodules affecting finger pads and histologic features of vasculitis may be better characterized as Osler nodes. Regardless of pathogenesis, these cutaneous findings serve as a minor clinical criterion in the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis when present.12

Candida infective endocarditis should be suspected in a patient with a history of valvular disease or prior infective endocarditis with fungemia, unexplained neurologic signs, or manifestations of peripheral embolization despite negative blood cultures.3 Particularly in the setting of negative cardiac imaging, recognition of CIE requires heightened diagnostic acumen and clinicopathologic correlation. Although culture and pathologic examination of valvular vegetations represents the gold standard for diagnosis of CIE, aspiration and culture of easily accessible septic emboli may provide rapid identification of the etiologic pathogen. In 1976, Alpert et al13 identified C albicans from an aspirated Osler node. Postmortem examination revealed extensive involvement of the homograft valve and aortic root with C albicans.13 Many other examples exist in the literature demonstrating matching pathogenic isolates from microbiologic cultures of skin and blood.4,9,14,15 Thadepalli and Francis7 investigated 26 cases of endocarditis in heroin users in which the admitting diagnosis was endocarditis in only 4 cases. The etiologic pathogen was aspirated from secondary sites of localized infections secondary to emboli, including cutaneous lesions in 10 of the cases. Gram stain and culture revealed the causative organism leading to the ultimate diagnosis and management in 17 of 26 patients with endocarditis.7

The incidence of fungal endocarditis is increasing, with a reported 67% of cases caused by nosocomial infection.1 Given the rising incidence of fungal endocarditis and its accompanying diagnostic difficulties, including frequently negative blood cultures and cardiac imaging, clinicians must perform careful skin examinations, employ judicious use of skin biopsy, and carefully correlate clinical and pathologic findings to improve recognition of this disease and guide patient care.

- Arnold CJ, Johnson M, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: an observational cohort study with a focus on therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2365. doi:10.1128/AAC.04867-14

- Chaudhary SC, Sawlani KK, Arora R, et al. Native aortic valve fungal endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012007144. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007144

- Ellis ME, Al-Abdely H, Sandridge A, et al. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:50-62. doi:10.1086/317550

- Gil MP, Velasco M, Botella R, et al. Janeway lesions: differential diagnosis with Osler’s nodes. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:673-674. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb04025.x

- Gomes RT, Tiberto LR, Bello VNM, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of infective endocarditis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:92-94.

- Yee JM. Osler’s nodes and the recognition of infective endocarditis: a lesion of diagnostic importance. South Med J. 1987;80:753-757.

- Thadepalli H, Francis C. Diagnostic clues in metastatic lesions of endocarditia in addicts. West J Med. 1978;128:1-5.

- Kerr A Jr. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis. Charles C. Thomas; 1955.

- Kerr A Jr, Tan JS. Biopsies of the Janeway lesion of infective endocarditis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:124-129. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01113.x

- Marrie TJ. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Am J Med. 2008;121:105-106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.035

- Gunson TH, Oliver GF. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:251-255. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00397.x

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK, et al. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Am J Med. 1994;96:200-209.

- Alpert JS, Krous HF, Dalen JE, et al. Pathogenesis of Osler’s nodes. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:471-473. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-85-4-471

- Cardullo AC, Silvers DN, Grossman ME. Janeway lesions and Osler’s nodes: a review of histopathologic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1088-1090. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70157-D

- Vinson RP, Chung A, Elston DM, et al. Septic microemboli in a Janeway lesion of bacterial endocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:984-985. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90125-5

- Arnold CJ, Johnson M, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: an observational cohort study with a focus on therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2365. doi:10.1128/AAC.04867-14

- Chaudhary SC, Sawlani KK, Arora R, et al. Native aortic valve fungal endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012007144. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007144

- Ellis ME, Al-Abdely H, Sandridge A, et al. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:50-62. doi:10.1086/317550

- Gil MP, Velasco M, Botella R, et al. Janeway lesions: differential diagnosis with Osler’s nodes. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:673-674. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb04025.x

- Gomes RT, Tiberto LR, Bello VNM, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of infective endocarditis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:92-94.

- Yee JM. Osler’s nodes and the recognition of infective endocarditis: a lesion of diagnostic importance. South Med J. 1987;80:753-757.

- Thadepalli H, Francis C. Diagnostic clues in metastatic lesions of endocarditia in addicts. West J Med. 1978;128:1-5.

- Kerr A Jr. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis. Charles C. Thomas; 1955.

- Kerr A Jr, Tan JS. Biopsies of the Janeway lesion of infective endocarditis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:124-129. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1979.tb01113.x

- Marrie TJ. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Am J Med. 2008;121:105-106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.035

- Gunson TH, Oliver GF. Osler’s nodes and Janeway lesions. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:251-255. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00397.x

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK, et al. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Am J Med. 1994;96:200-209.

- Alpert JS, Krous HF, Dalen JE, et al. Pathogenesis of Osler’s nodes. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:471-473. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-85-4-471

- Cardullo AC, Silvers DN, Grossman ME. Janeway lesions and Osler’s nodes: a review of histopathologic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1088-1090. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70157-D

- Vinson RP, Chung A, Elston DM, et al. Septic microemboli in a Janeway lesion of bacterial endocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:984-985. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90125-5

PRACTICE POINTS

- Fungal infective endocarditis is rare, and diagnostic tests such as blood cultures and echocardiography may not detect the disease.

- The mortality rate of fungal endocarditis is high, with improved clinical outcomes if diagnosed and treated early.

- Clinicopathologic correlation between integumentary examination and skin biopsy findings may provide timely diagnosis, thereby guiding appropriate therapy.

Hyperkeratotic Nummular Plaques on the Upper Trunk

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

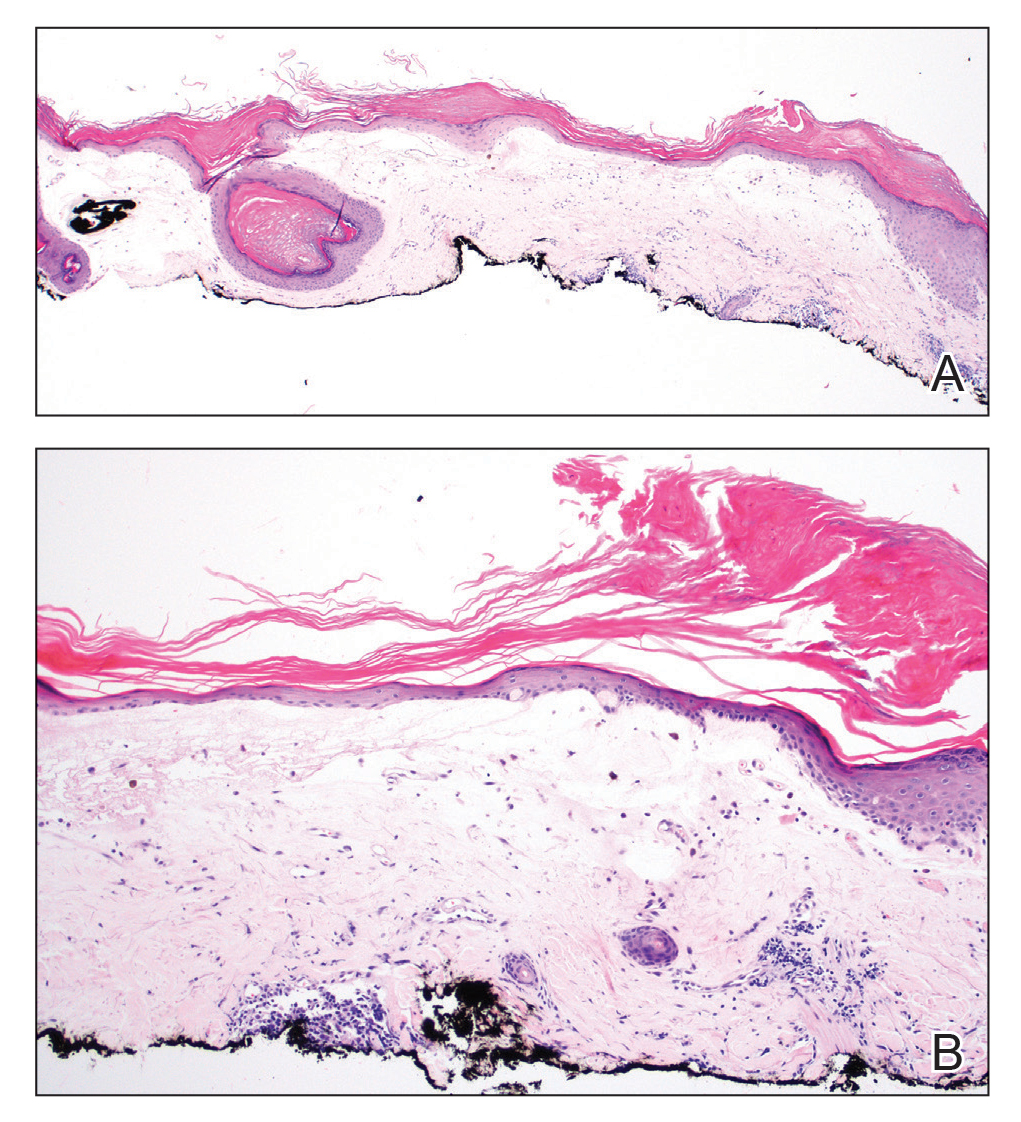

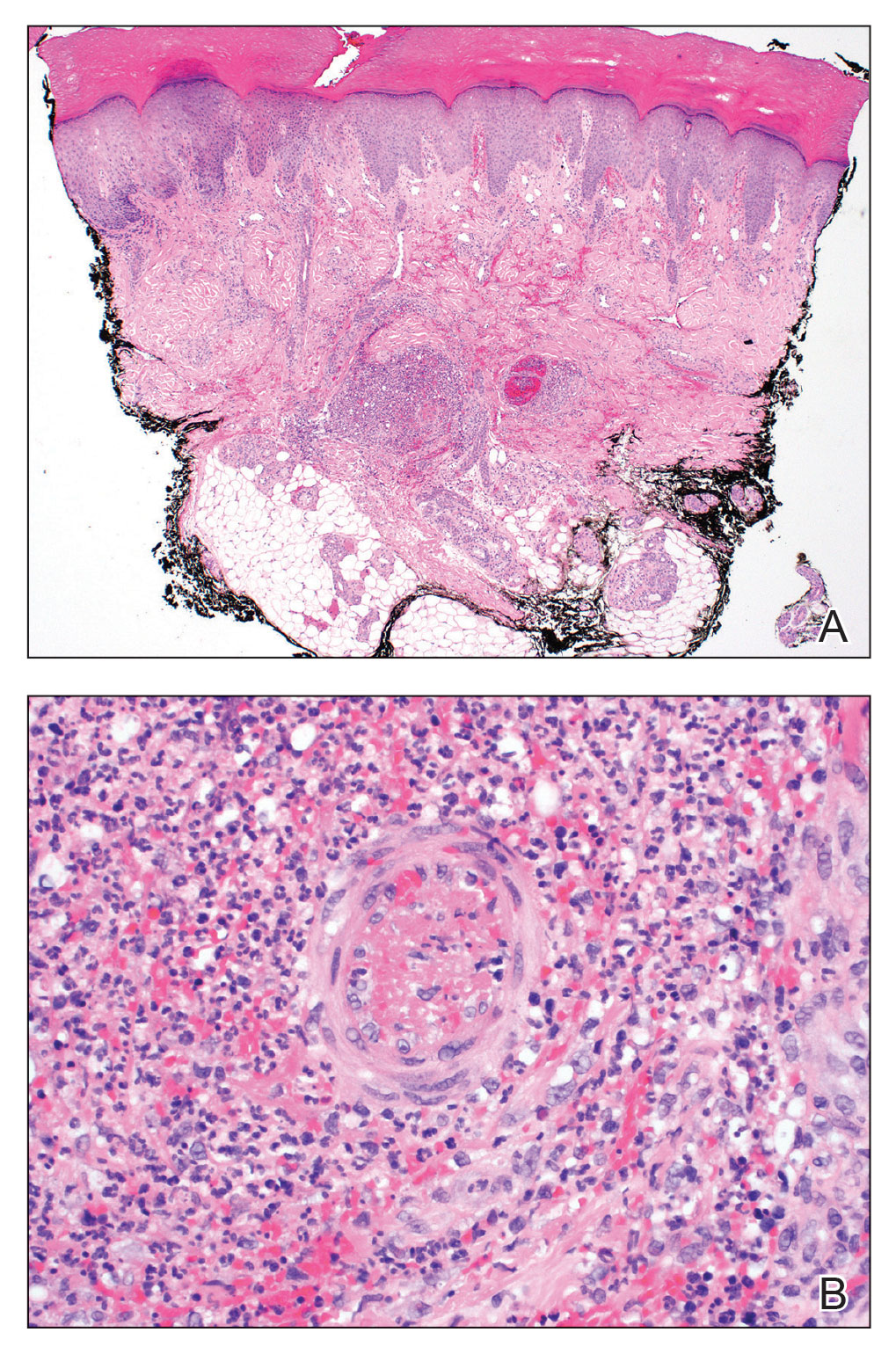

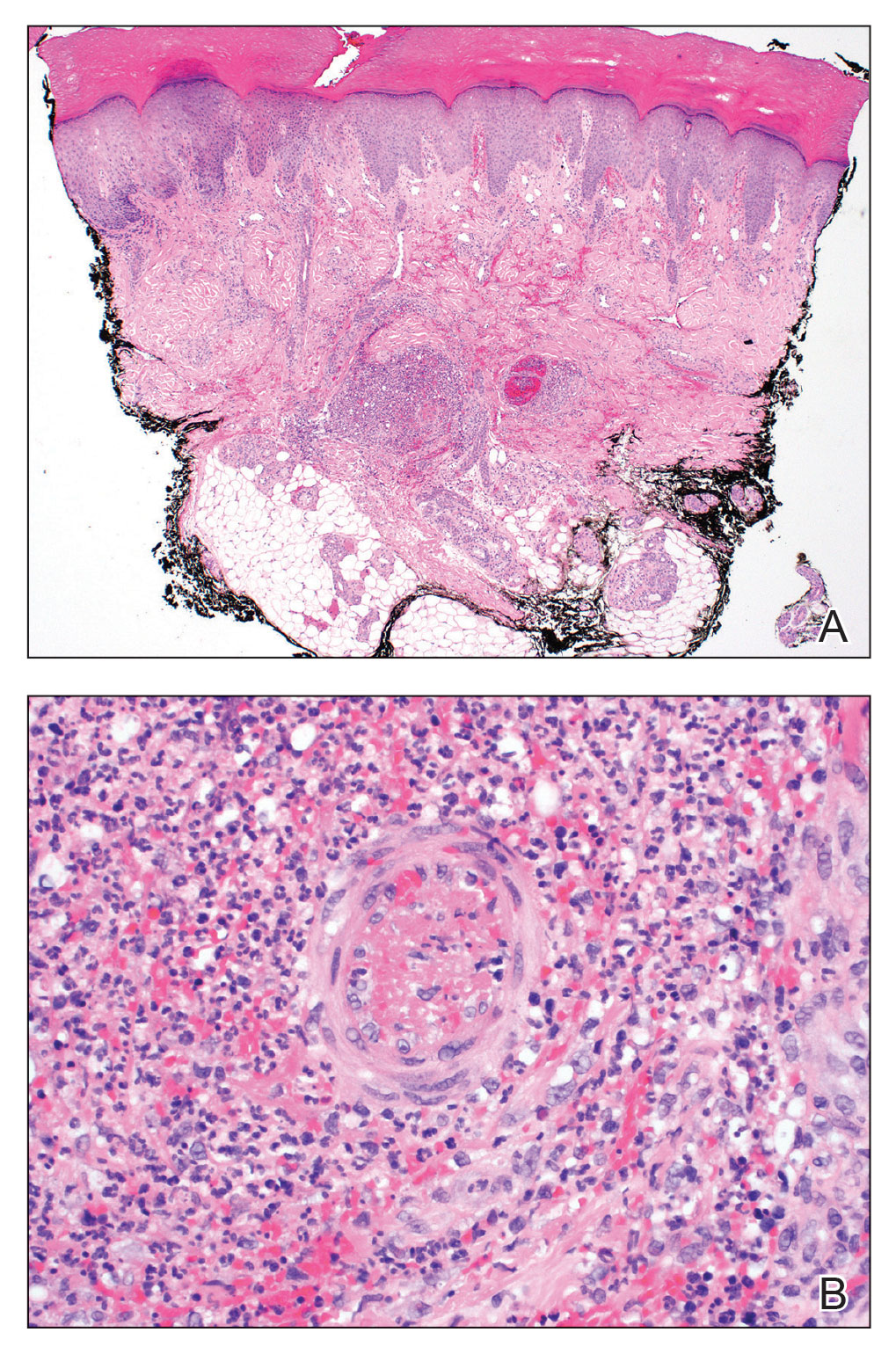

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

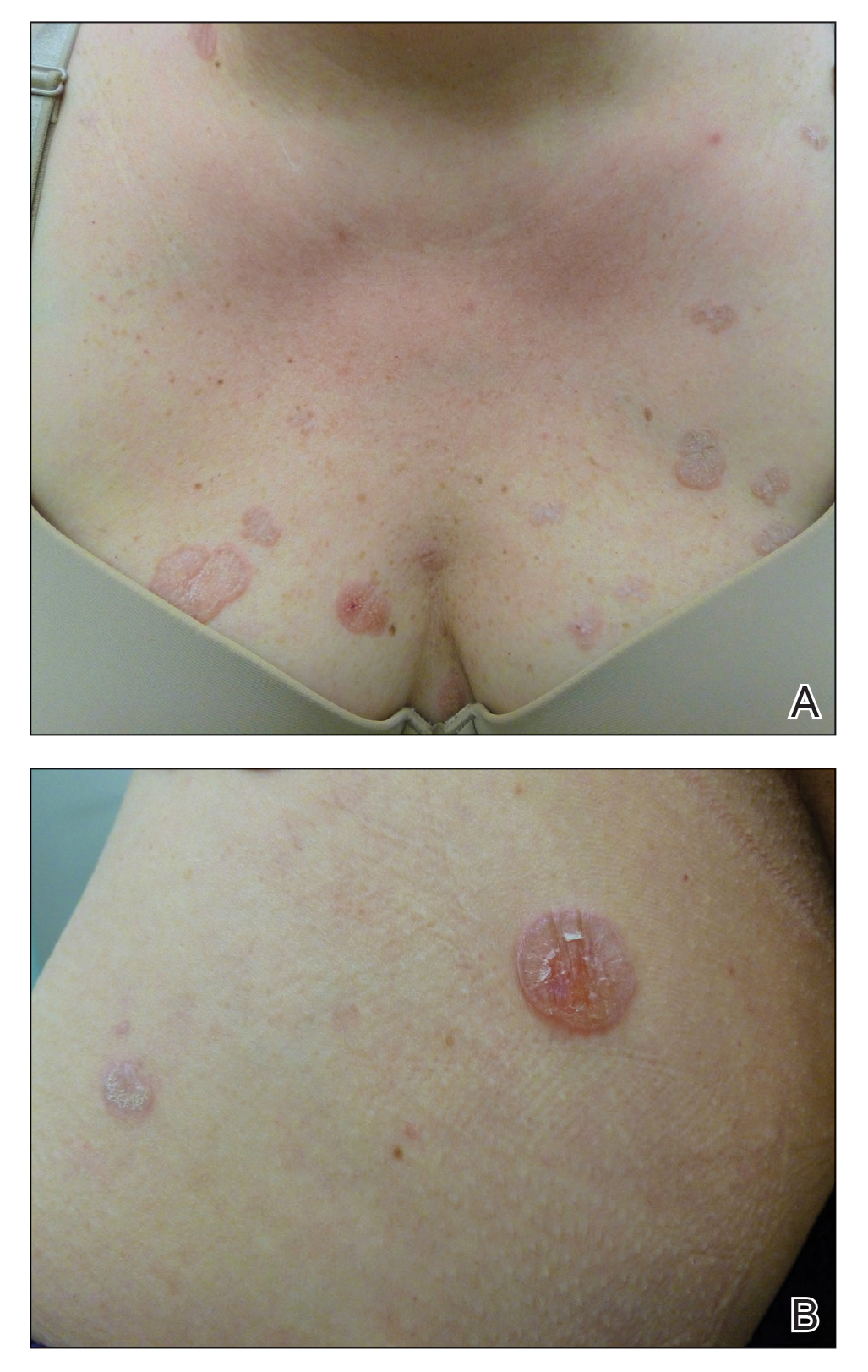

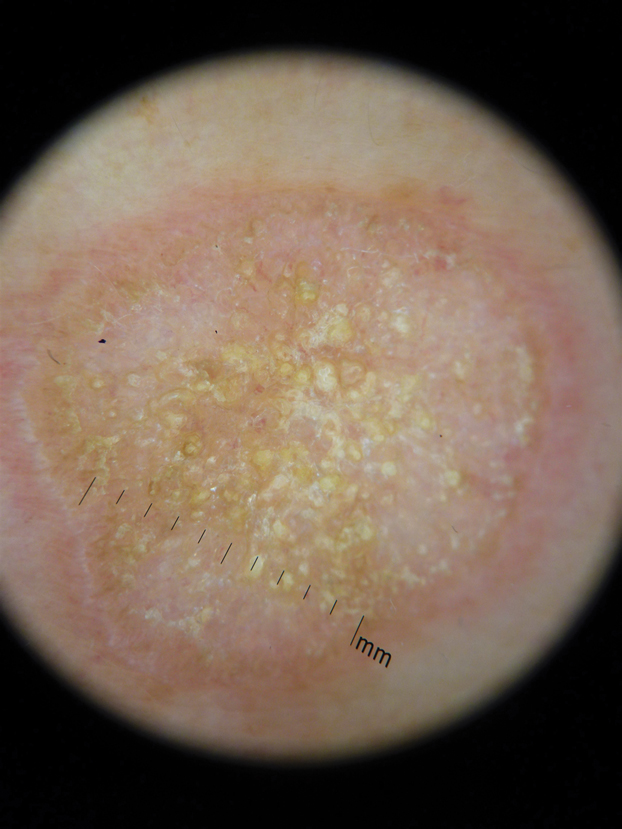

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

A 48-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis presented with papules and plaques on the upper trunk, proximal extremities, and volar wrists. Clear fluid–filled bullae occasionally developed within the plaques and subsequently ruptured and healed. Aside from intermittent lesion tenderness and irritation with the formation and rupture of the bullae, the patient’s plaques were asymptomatic, and she specifically denied pruritus. A review of systems revealed a history of genital irritation evaluated by a gynecologist; nystatin–triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied as needed provided relief. The patient denied any recent flares or any new or changing oral mucosa findings or symptoms, preceding medications, or family history of similar lesions. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, round, pink plaques with keratotic scale scattered across the upper trunk and central chest. The bilateral volar wrists were surfaced by well-circumscribed, thin, pink to violaceous, hyperkeratotic papules.