User login

Should a Patient Who Requests Alcohol Detoxification Be Admitted or Treated as Outpatient?

Case

A 42-year-old man with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), hypertension, and alcohol use disorder (AUD) presents to the ED requesting alcohol detoxification. He has had six admissions in the last six months for alcohol detoxification. Two years ago, the patient had a documented alcohol withdrawal seizure. His last drink was eight hours ago, and he currently drinks a liter of vodka a day. On exam, his pulse rate is 126 bpm, and his blood pressure is 162/91 mm Hg. He appears anxious and has bilateral hand tremors. His serum ethanol level is 388.6 mg/dL.

Overview

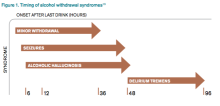

DSM-5 integrated alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence that were previously classified in DSM-IV into AUDs with mild, moderate, and severe subclassifications. AUDs are the most serious substance abuse problem in the U.S. In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse is 17.8% and of alcohol dependence is 12.5%.1–3 One study estimates that 24% of adult patients brought to the ED by ambulance suffer from alcoholism, and approximately 10% to 32% of hospitalized medical patients have an AUD.4–8 Patients who stop drinking will develop alcohol withdrawal as early as six hours after their last drink (see Figure 1). The majority of patients at risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) will develop only minor uncomplicated symptoms, but up to 20% will develop symptoms associated with complicated AWS, including withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens (DT).9 It is not entirely clear why some individuals suffer from more severe withdrawal symptoms than others, but genetic predisposition may play a role.10

DT is a syndrome characterized by agitation, disorientation, hallucinations, and autonomic instability (tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis) in the setting of acute reduction or abstinence from alcohol and is associated with a mortality rate as high as 20%.11 Complicated AWS is associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality, longer lengths of stay, inflated costs of care, increased burden and frustration of nursing and medical staff, and worse cognitive functioning.9 In 80% of cases, the symptoms of uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal do not require aggressive medical intervention and usually disappear within two to seven days of the last drink.12 Physicians making triage decisions for patients who present to the ED in need of detoxification face a difficult dilemma concerning inpatient versus outpatient treatment.

Review of the Data

The literature on both inpatient and outpatient management and treatment of AWS is well-described. Currently, there are no guidelines or consensus on whether to admit patients with alcohol abuse syndromes to the hospital when the request for detoxification is made. Admission should be considered for all patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal who present to the ED.13 Patients with mild AWS may be discharged if they do not require admission for an additional medical condition, but patients experiencing moderate to severe withdrawal require admission for monitoring and treatment. Many physicians use a simple assessment of past history of DT and pulse rate, which may be easily evaluated in clinical settings, to readily identify patients who are at high risk of developing DT during an alcohol dependence period.14

Since 1978, the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) has been consistently used for both monitoring patients with alcohol withdrawal and for making an initial assessment. CIWA-Ar was developed as a revised scale and is frequently used to monitor the severity of ongoing alcohol withdrawal and the response to treatment for the clinical care of patients in alcohol withdrawal (see Figure 2). CIWA-Ar was not developed to identify patients at risk for AWS but is frequently used to determine if patients require admission to the hospital for detoxification.15 Patients with CIWA-Ar scores > 15 require inpatient detoxification. Patients with scores between 8 and 15 should be admitted if they have a history of prior seizures or DT but could otherwise be considered for outpatient detoxification. Patients with scores < 8, which are considered mild alcohol withdrawal, can likely be safely treated as outpatients unless they have a history of DT or alcohol withdrawal seizures.16 Because symptoms of severe alcohol withdrawal are often not present for more than six hours after the patient’s last drink, or often longer, CIWA-Ar is limited and does not identify patients who are otherwise at high risk for complicated withdrawal. A protocol was developed incorporating the patient’s history of alcohol withdrawal seizure, DT, and the CIWA to evaluate the outcome of outpatient versus inpatient detoxification.16

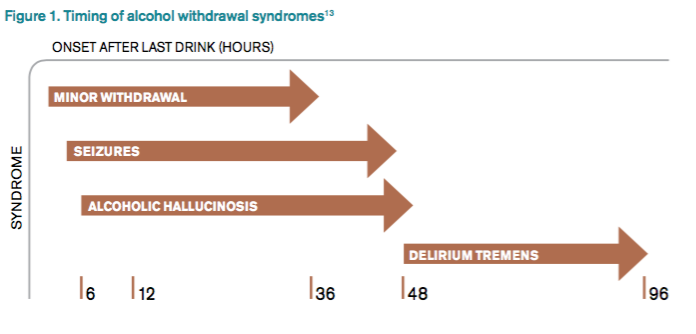

The most promising tool to screen patients for AWS was developed recently by researchers at Stanford University in Stanford, Calif., using an extensive systematic literature search to identify evidence-based clinical factors associated with the development of AWS.15 The Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) was subsequently constructed from 10 items correlating with complicated AWS (see Figure 3). When using a PAWSS score cutoff of ≥ 4, the predictive value of identifying a patient who is at risk for complicated withdrawal is significantly increased to 93.1%. This tool has only been used in medically ill patients but could be extrapolated for use in patients who present to an acute-care setting requesting inpatient detoxification.

Patients presenting to the ED with alcohol withdrawal seizures have been shown to have an associated 35% risk of progression to DT when found to have a low platelet count, low blood pyridoxine, and a high blood level of homocysteine. In another retrospective cohort study in Hepatology, three clinical features were identified to be associated with an increased risk for DT: alcohol dependence, a prior history of DT, and a higher pulse rate at admission (> 100 bpm).14

Instructions for the assessment of the patient who requests detoxification are as follows:

- A patient whose last drink of alcohol was more than five days ago and who shows no signs of withdrawal is unlikely to develop significant withdrawal symptoms and does not require inpatient detoxification.

- Other medical and psychiatric conditions should be evaluated for admission including alcohol use disorder complications.

- Calculate CIWA-Ar score:

Scores < 8 may not need detoxification; consider calculating PAWSS score.

Scores of 8 to 15 without symptoms of DT or seizures can be treated as an outpatient detoxification if no contraindication.

Scores of ≥ 15 should be admitted to the hospital.

- Calculate PAWSS score:

Scores ≥ 4 suggest high risk for moderate to severe complicated AWS, and admission should be considered.

Scores < 4 suggest lower risk for complicated AWS, and outpatient treatment should be considered if patients do not have a medical or surgical diagnosis requiring admission.

Back to the Case

At the time of his presentation, the patient was beginning to show signs of early withdrawal symptoms, including tremor and tachycardia, despite having an elevated blood alcohol level. This patient had a PAWSS score of 6, placing him at increased risk of complicated AWS, and a CIWA-Ar score of 13. He was subsequently admitted to the hospital, and symptom-triggered therapy for treatment of his alcohol withdrawal was used. The patient’s CIWA-Ar score peaked at 21 some 24 hours after his last drink. The patient otherwise had an uncomplicated four-day hospital course due to persistent nausea.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists unsure of which patients should be admitted for alcohol detoxification can use the PAWSS tool and an initial CIWA-Ar score to help determine a patient’s risk for developing complicated AWS. TH

Dr. Velasquez and Dr. Kornsawad are assistant professors and hospitalists at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Dr. Velasquez also serves as assistant professor and hospitalist at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System serving the San Antonio area.

References

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorder and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

- Lieber CS. Medical disorders of alcoholism. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(16):1058-1065.

- Hasin SD, Stinson SF, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830-842.

- Whiteman PJ, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR. Alcoholism in the emergency department: an epidemiologic study. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(1):14-20.

- Nielson SD, Storgarrd H, Moesgarrd F, Gluud C. Prevalence of alcohol problems among adult somatic in-patients of a Copenhagen hospital. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29(5):583-590.

- Smothers BA, Yahr HT, Ruhl CE. Detection of alcohol use disorders in general hospital admissions in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(7):749-756.

- Dolman JM, Hawkes ND. Combining the audit questionnaire and biochemical markers to assess alcohol use and risk of alcohol withdrawal in medical inpatients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(6):515-519.

- Doering-Silveira J, Fidalgo TM, Nascimento CL, et al. Assessing alcohol dependence in hospitalized patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(6):5783-5791.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Das S, et al. Prospective validation study of the prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale (PAWSS) in medically ill inpatients: a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(5):509-518.

- Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

- Turner RC, Lichstein PR, Pedan Jr JG, Busher JT, Waivers LE. Alcohol withdrawal syndromes: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(5):432-444.

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492-501.

- Stehman CR, Mycyk MB. A rational approach to the treatment of alcohol withdrawal in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):734-742.

- Lee JH, Jang MK, Lee JY, et al. Clinical predictors for delirium tremens in alcohol dependence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(12):1833-1837.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Ashouri JF, et al. The “prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale” (PAWSS): systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;48(4):375-390.

- Stephens JR, Liles AE, Dancel R, Gilchrist M, Kirsch J, DeWalt DA. Who needs inpatient detox? Development and implementation of a hospitalist protocol for the evaluation of patients for alcohol detoxification. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):587-593.

Case

A 42-year-old man with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), hypertension, and alcohol use disorder (AUD) presents to the ED requesting alcohol detoxification. He has had six admissions in the last six months for alcohol detoxification. Two years ago, the patient had a documented alcohol withdrawal seizure. His last drink was eight hours ago, and he currently drinks a liter of vodka a day. On exam, his pulse rate is 126 bpm, and his blood pressure is 162/91 mm Hg. He appears anxious and has bilateral hand tremors. His serum ethanol level is 388.6 mg/dL.

Overview

DSM-5 integrated alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence that were previously classified in DSM-IV into AUDs with mild, moderate, and severe subclassifications. AUDs are the most serious substance abuse problem in the U.S. In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse is 17.8% and of alcohol dependence is 12.5%.1–3 One study estimates that 24% of adult patients brought to the ED by ambulance suffer from alcoholism, and approximately 10% to 32% of hospitalized medical patients have an AUD.4–8 Patients who stop drinking will develop alcohol withdrawal as early as six hours after their last drink (see Figure 1). The majority of patients at risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) will develop only minor uncomplicated symptoms, but up to 20% will develop symptoms associated with complicated AWS, including withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens (DT).9 It is not entirely clear why some individuals suffer from more severe withdrawal symptoms than others, but genetic predisposition may play a role.10

DT is a syndrome characterized by agitation, disorientation, hallucinations, and autonomic instability (tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis) in the setting of acute reduction or abstinence from alcohol and is associated with a mortality rate as high as 20%.11 Complicated AWS is associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality, longer lengths of stay, inflated costs of care, increased burden and frustration of nursing and medical staff, and worse cognitive functioning.9 In 80% of cases, the symptoms of uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal do not require aggressive medical intervention and usually disappear within two to seven days of the last drink.12 Physicians making triage decisions for patients who present to the ED in need of detoxification face a difficult dilemma concerning inpatient versus outpatient treatment.

Review of the Data

The literature on both inpatient and outpatient management and treatment of AWS is well-described. Currently, there are no guidelines or consensus on whether to admit patients with alcohol abuse syndromes to the hospital when the request for detoxification is made. Admission should be considered for all patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal who present to the ED.13 Patients with mild AWS may be discharged if they do not require admission for an additional medical condition, but patients experiencing moderate to severe withdrawal require admission for monitoring and treatment. Many physicians use a simple assessment of past history of DT and pulse rate, which may be easily evaluated in clinical settings, to readily identify patients who are at high risk of developing DT during an alcohol dependence period.14

Since 1978, the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) has been consistently used for both monitoring patients with alcohol withdrawal and for making an initial assessment. CIWA-Ar was developed as a revised scale and is frequently used to monitor the severity of ongoing alcohol withdrawal and the response to treatment for the clinical care of patients in alcohol withdrawal (see Figure 2). CIWA-Ar was not developed to identify patients at risk for AWS but is frequently used to determine if patients require admission to the hospital for detoxification.15 Patients with CIWA-Ar scores > 15 require inpatient detoxification. Patients with scores between 8 and 15 should be admitted if they have a history of prior seizures or DT but could otherwise be considered for outpatient detoxification. Patients with scores < 8, which are considered mild alcohol withdrawal, can likely be safely treated as outpatients unless they have a history of DT or alcohol withdrawal seizures.16 Because symptoms of severe alcohol withdrawal are often not present for more than six hours after the patient’s last drink, or often longer, CIWA-Ar is limited and does not identify patients who are otherwise at high risk for complicated withdrawal. A protocol was developed incorporating the patient’s history of alcohol withdrawal seizure, DT, and the CIWA to evaluate the outcome of outpatient versus inpatient detoxification.16

The most promising tool to screen patients for AWS was developed recently by researchers at Stanford University in Stanford, Calif., using an extensive systematic literature search to identify evidence-based clinical factors associated with the development of AWS.15 The Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) was subsequently constructed from 10 items correlating with complicated AWS (see Figure 3). When using a PAWSS score cutoff of ≥ 4, the predictive value of identifying a patient who is at risk for complicated withdrawal is significantly increased to 93.1%. This tool has only been used in medically ill patients but could be extrapolated for use in patients who present to an acute-care setting requesting inpatient detoxification.

Patients presenting to the ED with alcohol withdrawal seizures have been shown to have an associated 35% risk of progression to DT when found to have a low platelet count, low blood pyridoxine, and a high blood level of homocysteine. In another retrospective cohort study in Hepatology, three clinical features were identified to be associated with an increased risk for DT: alcohol dependence, a prior history of DT, and a higher pulse rate at admission (> 100 bpm).14

Instructions for the assessment of the patient who requests detoxification are as follows:

- A patient whose last drink of alcohol was more than five days ago and who shows no signs of withdrawal is unlikely to develop significant withdrawal symptoms and does not require inpatient detoxification.

- Other medical and psychiatric conditions should be evaluated for admission including alcohol use disorder complications.

- Calculate CIWA-Ar score:

Scores < 8 may not need detoxification; consider calculating PAWSS score.

Scores of 8 to 15 without symptoms of DT or seizures can be treated as an outpatient detoxification if no contraindication.

Scores of ≥ 15 should be admitted to the hospital.

- Calculate PAWSS score:

Scores ≥ 4 suggest high risk for moderate to severe complicated AWS, and admission should be considered.

Scores < 4 suggest lower risk for complicated AWS, and outpatient treatment should be considered if patients do not have a medical or surgical diagnosis requiring admission.

Back to the Case

At the time of his presentation, the patient was beginning to show signs of early withdrawal symptoms, including tremor and tachycardia, despite having an elevated blood alcohol level. This patient had a PAWSS score of 6, placing him at increased risk of complicated AWS, and a CIWA-Ar score of 13. He was subsequently admitted to the hospital, and symptom-triggered therapy for treatment of his alcohol withdrawal was used. The patient’s CIWA-Ar score peaked at 21 some 24 hours after his last drink. The patient otherwise had an uncomplicated four-day hospital course due to persistent nausea.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists unsure of which patients should be admitted for alcohol detoxification can use the PAWSS tool and an initial CIWA-Ar score to help determine a patient’s risk for developing complicated AWS. TH

Dr. Velasquez and Dr. Kornsawad are assistant professors and hospitalists at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Dr. Velasquez also serves as assistant professor and hospitalist at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System serving the San Antonio area.

References

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorder and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

- Lieber CS. Medical disorders of alcoholism. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(16):1058-1065.

- Hasin SD, Stinson SF, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830-842.

- Whiteman PJ, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR. Alcoholism in the emergency department: an epidemiologic study. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(1):14-20.

- Nielson SD, Storgarrd H, Moesgarrd F, Gluud C. Prevalence of alcohol problems among adult somatic in-patients of a Copenhagen hospital. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29(5):583-590.

- Smothers BA, Yahr HT, Ruhl CE. Detection of alcohol use disorders in general hospital admissions in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(7):749-756.

- Dolman JM, Hawkes ND. Combining the audit questionnaire and biochemical markers to assess alcohol use and risk of alcohol withdrawal in medical inpatients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(6):515-519.

- Doering-Silveira J, Fidalgo TM, Nascimento CL, et al. Assessing alcohol dependence in hospitalized patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(6):5783-5791.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Das S, et al. Prospective validation study of the prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale (PAWSS) in medically ill inpatients: a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(5):509-518.

- Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

- Turner RC, Lichstein PR, Pedan Jr JG, Busher JT, Waivers LE. Alcohol withdrawal syndromes: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(5):432-444.

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492-501.

- Stehman CR, Mycyk MB. A rational approach to the treatment of alcohol withdrawal in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):734-742.

- Lee JH, Jang MK, Lee JY, et al. Clinical predictors for delirium tremens in alcohol dependence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(12):1833-1837.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Ashouri JF, et al. The “prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale” (PAWSS): systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;48(4):375-390.

- Stephens JR, Liles AE, Dancel R, Gilchrist M, Kirsch J, DeWalt DA. Who needs inpatient detox? Development and implementation of a hospitalist protocol for the evaluation of patients for alcohol detoxification. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):587-593.

Case

A 42-year-old man with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), hypertension, and alcohol use disorder (AUD) presents to the ED requesting alcohol detoxification. He has had six admissions in the last six months for alcohol detoxification. Two years ago, the patient had a documented alcohol withdrawal seizure. His last drink was eight hours ago, and he currently drinks a liter of vodka a day. On exam, his pulse rate is 126 bpm, and his blood pressure is 162/91 mm Hg. He appears anxious and has bilateral hand tremors. His serum ethanol level is 388.6 mg/dL.

Overview

DSM-5 integrated alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence that were previously classified in DSM-IV into AUDs with mild, moderate, and severe subclassifications. AUDs are the most serious substance abuse problem in the U.S. In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse is 17.8% and of alcohol dependence is 12.5%.1–3 One study estimates that 24% of adult patients brought to the ED by ambulance suffer from alcoholism, and approximately 10% to 32% of hospitalized medical patients have an AUD.4–8 Patients who stop drinking will develop alcohol withdrawal as early as six hours after their last drink (see Figure 1). The majority of patients at risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) will develop only minor uncomplicated symptoms, but up to 20% will develop symptoms associated with complicated AWS, including withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens (DT).9 It is not entirely clear why some individuals suffer from more severe withdrawal symptoms than others, but genetic predisposition may play a role.10

DT is a syndrome characterized by agitation, disorientation, hallucinations, and autonomic instability (tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis) in the setting of acute reduction or abstinence from alcohol and is associated with a mortality rate as high as 20%.11 Complicated AWS is associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality, longer lengths of stay, inflated costs of care, increased burden and frustration of nursing and medical staff, and worse cognitive functioning.9 In 80% of cases, the symptoms of uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal do not require aggressive medical intervention and usually disappear within two to seven days of the last drink.12 Physicians making triage decisions for patients who present to the ED in need of detoxification face a difficult dilemma concerning inpatient versus outpatient treatment.

Review of the Data

The literature on both inpatient and outpatient management and treatment of AWS is well-described. Currently, there are no guidelines or consensus on whether to admit patients with alcohol abuse syndromes to the hospital when the request for detoxification is made. Admission should be considered for all patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal who present to the ED.13 Patients with mild AWS may be discharged if they do not require admission for an additional medical condition, but patients experiencing moderate to severe withdrawal require admission for monitoring and treatment. Many physicians use a simple assessment of past history of DT and pulse rate, which may be easily evaluated in clinical settings, to readily identify patients who are at high risk of developing DT during an alcohol dependence period.14

Since 1978, the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) has been consistently used for both monitoring patients with alcohol withdrawal and for making an initial assessment. CIWA-Ar was developed as a revised scale and is frequently used to monitor the severity of ongoing alcohol withdrawal and the response to treatment for the clinical care of patients in alcohol withdrawal (see Figure 2). CIWA-Ar was not developed to identify patients at risk for AWS but is frequently used to determine if patients require admission to the hospital for detoxification.15 Patients with CIWA-Ar scores > 15 require inpatient detoxification. Patients with scores between 8 and 15 should be admitted if they have a history of prior seizures or DT but could otherwise be considered for outpatient detoxification. Patients with scores < 8, which are considered mild alcohol withdrawal, can likely be safely treated as outpatients unless they have a history of DT or alcohol withdrawal seizures.16 Because symptoms of severe alcohol withdrawal are often not present for more than six hours after the patient’s last drink, or often longer, CIWA-Ar is limited and does not identify patients who are otherwise at high risk for complicated withdrawal. A protocol was developed incorporating the patient’s history of alcohol withdrawal seizure, DT, and the CIWA to evaluate the outcome of outpatient versus inpatient detoxification.16

The most promising tool to screen patients for AWS was developed recently by researchers at Stanford University in Stanford, Calif., using an extensive systematic literature search to identify evidence-based clinical factors associated with the development of AWS.15 The Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) was subsequently constructed from 10 items correlating with complicated AWS (see Figure 3). When using a PAWSS score cutoff of ≥ 4, the predictive value of identifying a patient who is at risk for complicated withdrawal is significantly increased to 93.1%. This tool has only been used in medically ill patients but could be extrapolated for use in patients who present to an acute-care setting requesting inpatient detoxification.

Patients presenting to the ED with alcohol withdrawal seizures have been shown to have an associated 35% risk of progression to DT when found to have a low platelet count, low blood pyridoxine, and a high blood level of homocysteine. In another retrospective cohort study in Hepatology, three clinical features were identified to be associated with an increased risk for DT: alcohol dependence, a prior history of DT, and a higher pulse rate at admission (> 100 bpm).14

Instructions for the assessment of the patient who requests detoxification are as follows:

- A patient whose last drink of alcohol was more than five days ago and who shows no signs of withdrawal is unlikely to develop significant withdrawal symptoms and does not require inpatient detoxification.

- Other medical and psychiatric conditions should be evaluated for admission including alcohol use disorder complications.

- Calculate CIWA-Ar score:

Scores < 8 may not need detoxification; consider calculating PAWSS score.

Scores of 8 to 15 without symptoms of DT or seizures can be treated as an outpatient detoxification if no contraindication.

Scores of ≥ 15 should be admitted to the hospital.

- Calculate PAWSS score:

Scores ≥ 4 suggest high risk for moderate to severe complicated AWS, and admission should be considered.

Scores < 4 suggest lower risk for complicated AWS, and outpatient treatment should be considered if patients do not have a medical or surgical diagnosis requiring admission.

Back to the Case

At the time of his presentation, the patient was beginning to show signs of early withdrawal symptoms, including tremor and tachycardia, despite having an elevated blood alcohol level. This patient had a PAWSS score of 6, placing him at increased risk of complicated AWS, and a CIWA-Ar score of 13. He was subsequently admitted to the hospital, and symptom-triggered therapy for treatment of his alcohol withdrawal was used. The patient’s CIWA-Ar score peaked at 21 some 24 hours after his last drink. The patient otherwise had an uncomplicated four-day hospital course due to persistent nausea.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists unsure of which patients should be admitted for alcohol detoxification can use the PAWSS tool and an initial CIWA-Ar score to help determine a patient’s risk for developing complicated AWS. TH

Dr. Velasquez and Dr. Kornsawad are assistant professors and hospitalists at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Dr. Velasquez also serves as assistant professor and hospitalist at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System serving the San Antonio area.

References

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorder and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

- Lieber CS. Medical disorders of alcoholism. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(16):1058-1065.

- Hasin SD, Stinson SF, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830-842.

- Whiteman PJ, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR. Alcoholism in the emergency department: an epidemiologic study. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(1):14-20.

- Nielson SD, Storgarrd H, Moesgarrd F, Gluud C. Prevalence of alcohol problems among adult somatic in-patients of a Copenhagen hospital. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29(5):583-590.

- Smothers BA, Yahr HT, Ruhl CE. Detection of alcohol use disorders in general hospital admissions in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(7):749-756.

- Dolman JM, Hawkes ND. Combining the audit questionnaire and biochemical markers to assess alcohol use and risk of alcohol withdrawal in medical inpatients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(6):515-519.

- Doering-Silveira J, Fidalgo TM, Nascimento CL, et al. Assessing alcohol dependence in hospitalized patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(6):5783-5791.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Das S, et al. Prospective validation study of the prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale (PAWSS) in medically ill inpatients: a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(5):509-518.

- Saitz R, O’Malley SS. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):881-907.

- Turner RC, Lichstein PR, Pedan Jr JG, Busher JT, Waivers LE. Alcohol withdrawal syndromes: a review of pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(5):432-444.

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492-501.

- Stehman CR, Mycyk MB. A rational approach to the treatment of alcohol withdrawal in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):734-742.

- Lee JH, Jang MK, Lee JY, et al. Clinical predictors for delirium tremens in alcohol dependence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(12):1833-1837.

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Ashouri JF, et al. The “prediction of alcohol withdrawal severity scale” (PAWSS): systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;48(4):375-390.

- Stephens JR, Liles AE, Dancel R, Gilchrist M, Kirsch J, DeWalt DA. Who needs inpatient detox? Development and implementation of a hospitalist protocol for the evaluation of patients for alcohol detoxification. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):587-593.