User login

Rapidly Evolving Papulonodular Eruption in the Axilla

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

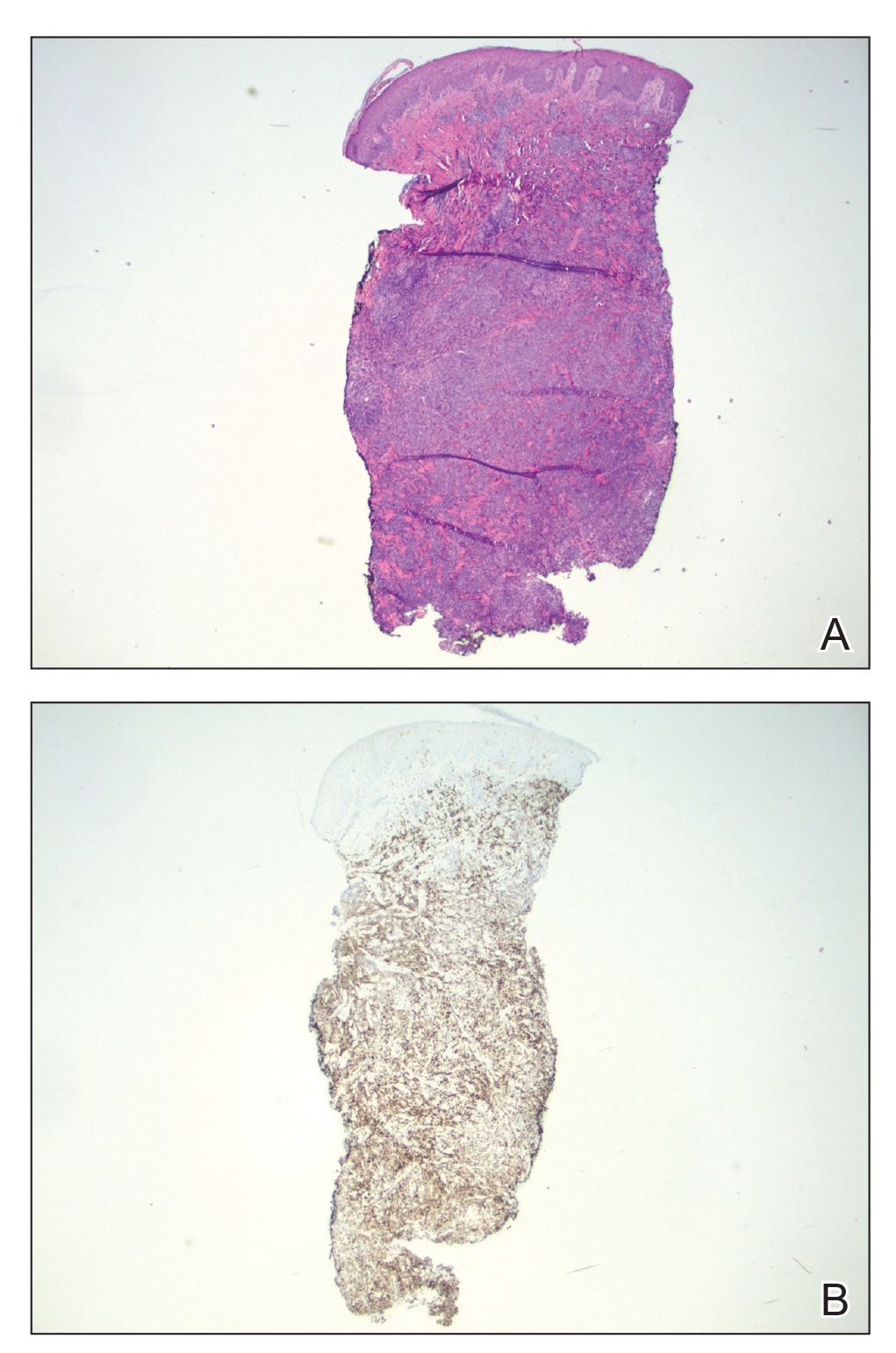

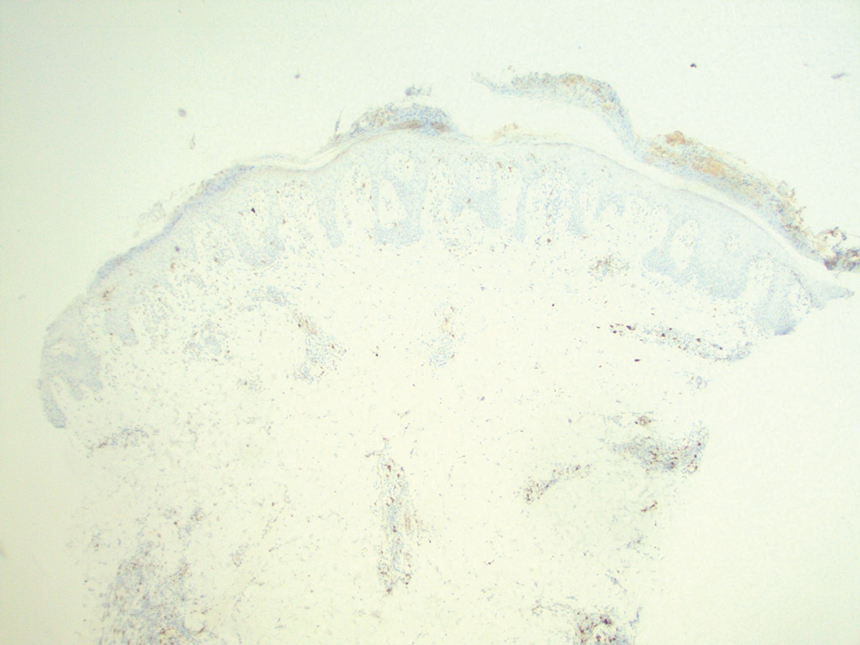

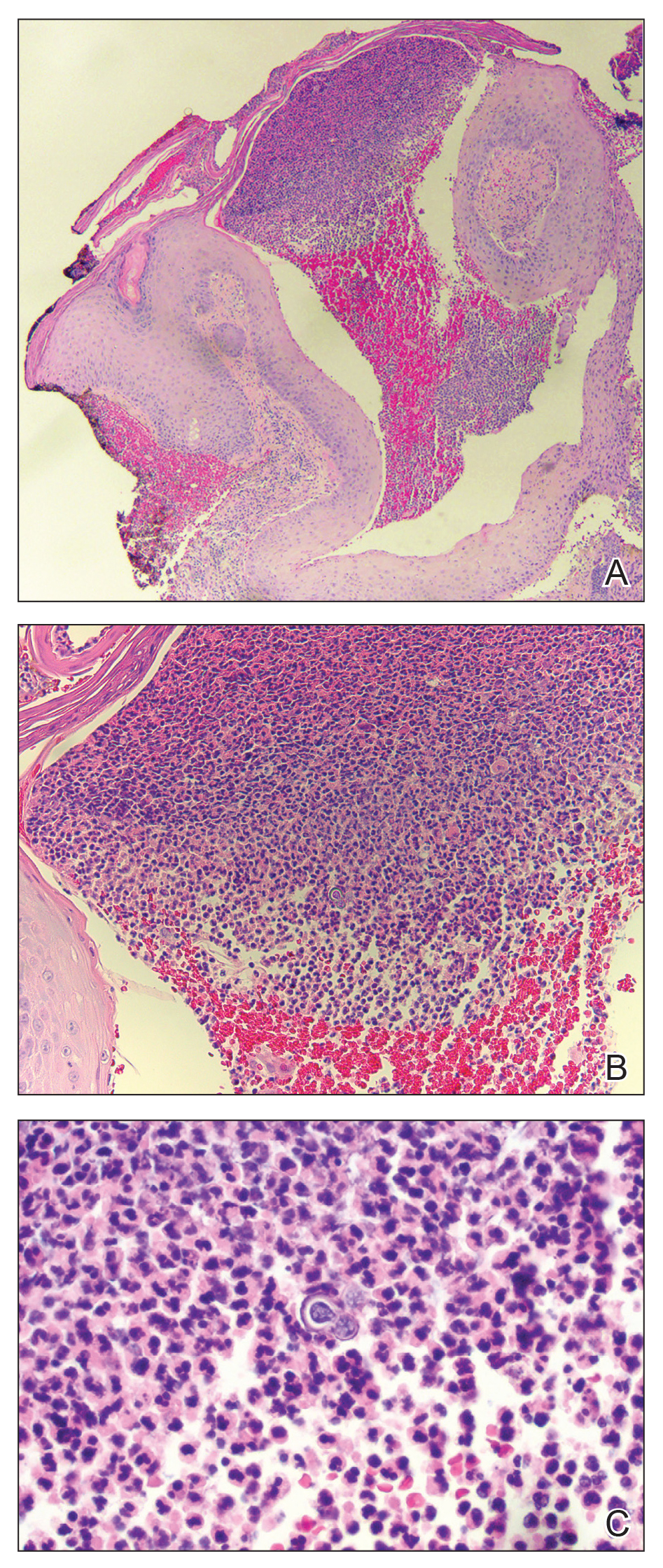

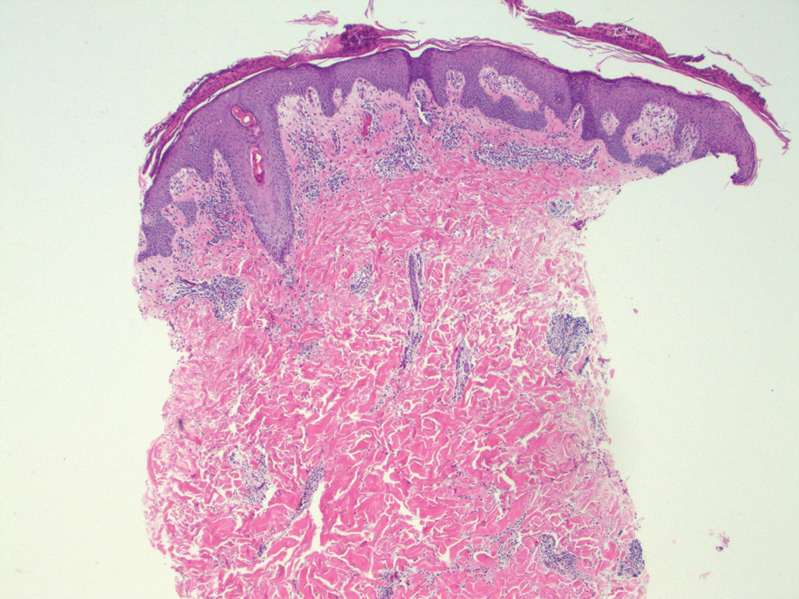

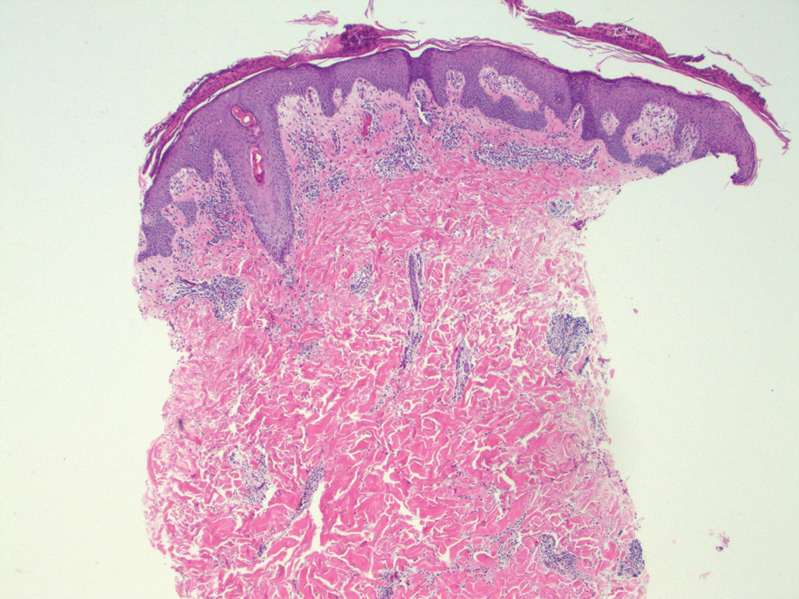

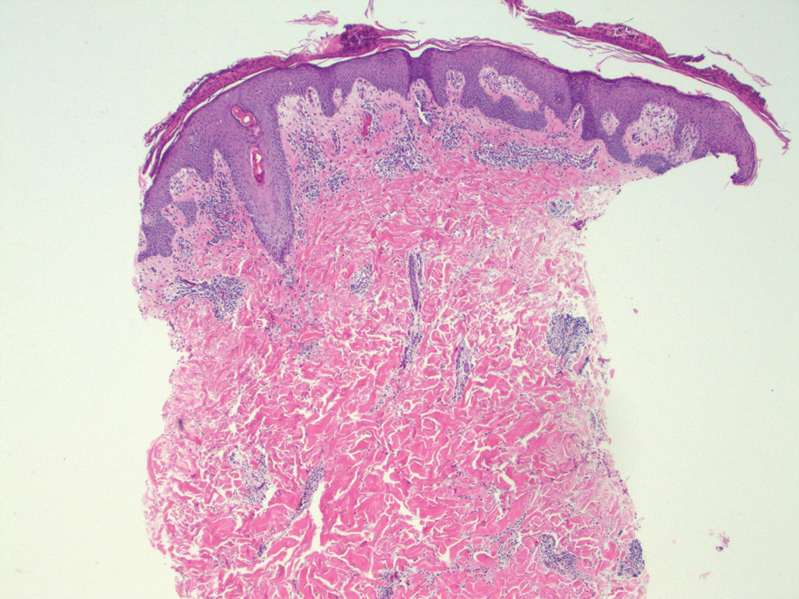

At the time of the initial visit, a punch biopsy was performed on the posterior shoulder girdle. Histopathology revealed mild epidermal spongiosis and acanthosis with associated parakeratosis and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes consistent with pityriasis rosea (Figure 1). Two weeks after the biopsy, the patient returned for suture removal and to discuss the biopsy results. The patient reported more evolving lesions despite completing the prescribed course of dicloxacillin. At this time, physical examination revealed the persistence of several reddishbrown papules along with new nodular lesions on the arms and thighs, some with central ulceration and crusting (Figure 2). A second biopsy of a nodular lesion on the right distal forearm was performed at this visit along with a superficial tissue culture, which was negative for bacterial or fungal elements. The biopsy revealed an atypical CD30+ lymphoid proliferation (Figure 3). These cells were strongly PD-L1 positive and also positive for CD3, CD4, and granzyme-B. Ki67 showed a high proliferation rate, and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were positive. Given these histologic findings and the clinical context of rapidly evolving skin lesions from small papules to nodular skin tumors, a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) was established.

Because of the notable pathologic discordance between the 2 biopsy specimens, re-evaluation of the initial specimen was requested. The initial biopsy was subsequently found to be CD30+ with an identical peak on gene rearrangement studies as the second biopsy, further validating the diagnosis of LyP (Figure 4). Our patient was offered low-dose methotrexate therapy but declined the treatment plan, as the skin lesions had begun to resolve.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with a characteristic recurrent and self-remitting disease course.1,2 Although it typically has a benign clinical course, it is histologically malignant and considered a low-grade variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. 2,3 The classic clinical presentation of LyP involves the presence of reddish-brown papules and nodules typically measuring less than 2.0 cm, which may show evidence of central ulceration, hemorrhage, necrosis, and/or crust formation.1-5 It is characteristic that a patient may present with these skin lesions in different stages of evolution and that biopsies of these lesions may reflect different histologic features depending on the age of the lesion, making a definitive diagnosis more difficult to obtain if not clinically correlated.1,2 Any part of the body may be involved; however, there appears to be a predilection for the trunk and extremities in most cases.1-3,5 The skin eruptions usually are asymptomatic, but pruritus is a commonly associated concern.1,2,4,5

Lymphomatoid papulosis can have a localized, clustered, or generalized distribution pattern and typically will spontaneously regress without treatment within 3 to 12 weeks of symptom onset.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis has a slight male predominance with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. It occurs most commonly between 35 and 45 years of age, though it can present at any age. The overall duration of the disease can range from months to decades.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis makes up approximately 15% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2,3 Although the overall prognosis is excellent, patients with LyP are at an increased risk of developing cutaneous or systemic lymphoma, most commonly mycosis fungoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, or Hodgkin lymphoma.1-3 This increased lifelong risk is the reason that patients with LyP must be followed long-term every 6 to 12 months for surveillance of emerging malignancy.1,2,6

The pathogenesis of LyP remains unknown. Some have hypothesized a possible viral trigger; however, there is insufficient data to support this theory.2,6 A diagnostic hallmark of LyP is its CD30 positivity, which is a known marker for T-cell activation.6 The spontaneous regression of skin lesions that is characteristic of LyP is believed to involve the interactions between CD30 and its ligand (CD30L), which may contribute to apoptosis of neoplastic T cells.2,3,6 With regards to the possible mechanisms contributing to tumor progression in LyP, a mutation in the transforming growth factor β receptor gene on CD30+ tumor cells within LyP lesions may allow for these cells to evade growth regulation and progress to lymphoma.2,6 A large percentage of LyP biopsy specimens show evidence of T-cell receptor gene monoclonal rearrangement, which can aid in establishing a diagnosis.1,2

The histologic features of LyP can vary greatly depending on the age of the lesion sampled.1,2 Histologic subtypes of LyP have been established, with type A being the most common (approximately 75% of cases), displaying a wedge-shaped infiltrate of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ T cells.1,2 Types B through E vary in histologic features, with the exception that all subtypes contain a CD30+ lymphocytic infiltrate.2,3

Treatment of LyP depends on the symptom/disease burden that the patient is experiencing. For patients with a limited number of nonscarring skin lesions in areas that are not cosmetically sensitive, observation is recommended. 1-3 For symptomatic patients with an extensive number of lesions, particularly those that may be scarring and/or in cosmetically sensitive areas, low-dose oral methotrexate therapy is considered first-line treatment.1-4 A methotrexate dose of 5 to 20 mg weekly can be effective in reducing the number and severity of lesions, with duration of treatment depending on clinical response.1,2 For patients who have contraindications to or who cannot tolerate oral methotrexate, phototherapy using psoralen plus UVA twice weekly for 6 to 8 weeks is another treatment option.1,2 Topical corticosteroids also can be used in children or for patients experiencing substantial pruritus.1,2,4 Oral or topical retinoids, topical carmustine or mechlorethamine, and brentuximab (an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody) are all alternative therapies that have shown some beneficial effects.1,2 In the event that any of the skin lesions do not spontaneously regress within a 3- to 12-week time frame, surgical excision or radiotherapy can be performed on those lesions.2

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL) is another CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with overlapping clinical and histopathological features of LyP. Recurrent crops of multiple lesions favor a diagnosis of LyP, whereas solitary lesions favor C-ALCL; however, multifocal C-ALCL cases may occur.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that characteristically presents in a patch, plaque, tumor progression. Although mycosis fungoides eventually may transform into a CD30+ lymphoma, our patient did not display the characteristic clinical progression to suggest this diagnosis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica also fall into the spectrum of clonal T-cell cutaneous disorders that more commonly affect the pediatric population. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta has a marked CD8+ lymphocyte infiltrate, whereas pityriasis lichenoides chronica has more CD4+ lymphocytes. These disorders typically do not stain positive for CD30.2

All patients with a diagnosis of LyP should maintain lifelong, regular, 6- to 12-month follow-up visits to monitor disease status and screen for any evidence of developing malignancy.1,2,6 A thorough review of clinical history, complete skin examination, and physical examination with a particular focus on detection of lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly should be included at every followup visit.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or weight loss are not typical features of LyP; therefore, patients who begin to develop these symptoms should be promptly evaluated for systemic lymphoma.1

- Kadin ME. Lymphomatoid papulosis. UpToDate website. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lymphomatoid-papulosis

- Willemze R. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2017:2141-2143.

- Wiznia LE, Cohen JM, Beasley JM, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt4xt046c9.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.013

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Kunishige JH, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-581. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2008.03024.x

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

At the time of the initial visit, a punch biopsy was performed on the posterior shoulder girdle. Histopathology revealed mild epidermal spongiosis and acanthosis with associated parakeratosis and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes consistent with pityriasis rosea (Figure 1). Two weeks after the biopsy, the patient returned for suture removal and to discuss the biopsy results. The patient reported more evolving lesions despite completing the prescribed course of dicloxacillin. At this time, physical examination revealed the persistence of several reddishbrown papules along with new nodular lesions on the arms and thighs, some with central ulceration and crusting (Figure 2). A second biopsy of a nodular lesion on the right distal forearm was performed at this visit along with a superficial tissue culture, which was negative for bacterial or fungal elements. The biopsy revealed an atypical CD30+ lymphoid proliferation (Figure 3). These cells were strongly PD-L1 positive and also positive for CD3, CD4, and granzyme-B. Ki67 showed a high proliferation rate, and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were positive. Given these histologic findings and the clinical context of rapidly evolving skin lesions from small papules to nodular skin tumors, a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) was established.

Because of the notable pathologic discordance between the 2 biopsy specimens, re-evaluation of the initial specimen was requested. The initial biopsy was subsequently found to be CD30+ with an identical peak on gene rearrangement studies as the second biopsy, further validating the diagnosis of LyP (Figure 4). Our patient was offered low-dose methotrexate therapy but declined the treatment plan, as the skin lesions had begun to resolve.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with a characteristic recurrent and self-remitting disease course.1,2 Although it typically has a benign clinical course, it is histologically malignant and considered a low-grade variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. 2,3 The classic clinical presentation of LyP involves the presence of reddish-brown papules and nodules typically measuring less than 2.0 cm, which may show evidence of central ulceration, hemorrhage, necrosis, and/or crust formation.1-5 It is characteristic that a patient may present with these skin lesions in different stages of evolution and that biopsies of these lesions may reflect different histologic features depending on the age of the lesion, making a definitive diagnosis more difficult to obtain if not clinically correlated.1,2 Any part of the body may be involved; however, there appears to be a predilection for the trunk and extremities in most cases.1-3,5 The skin eruptions usually are asymptomatic, but pruritus is a commonly associated concern.1,2,4,5

Lymphomatoid papulosis can have a localized, clustered, or generalized distribution pattern and typically will spontaneously regress without treatment within 3 to 12 weeks of symptom onset.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis has a slight male predominance with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. It occurs most commonly between 35 and 45 years of age, though it can present at any age. The overall duration of the disease can range from months to decades.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis makes up approximately 15% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2,3 Although the overall prognosis is excellent, patients with LyP are at an increased risk of developing cutaneous or systemic lymphoma, most commonly mycosis fungoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, or Hodgkin lymphoma.1-3 This increased lifelong risk is the reason that patients with LyP must be followed long-term every 6 to 12 months for surveillance of emerging malignancy.1,2,6

The pathogenesis of LyP remains unknown. Some have hypothesized a possible viral trigger; however, there is insufficient data to support this theory.2,6 A diagnostic hallmark of LyP is its CD30 positivity, which is a known marker for T-cell activation.6 The spontaneous regression of skin lesions that is characteristic of LyP is believed to involve the interactions between CD30 and its ligand (CD30L), which may contribute to apoptosis of neoplastic T cells.2,3,6 With regards to the possible mechanisms contributing to tumor progression in LyP, a mutation in the transforming growth factor β receptor gene on CD30+ tumor cells within LyP lesions may allow for these cells to evade growth regulation and progress to lymphoma.2,6 A large percentage of LyP biopsy specimens show evidence of T-cell receptor gene monoclonal rearrangement, which can aid in establishing a diagnosis.1,2

The histologic features of LyP can vary greatly depending on the age of the lesion sampled.1,2 Histologic subtypes of LyP have been established, with type A being the most common (approximately 75% of cases), displaying a wedge-shaped infiltrate of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ T cells.1,2 Types B through E vary in histologic features, with the exception that all subtypes contain a CD30+ lymphocytic infiltrate.2,3

Treatment of LyP depends on the symptom/disease burden that the patient is experiencing. For patients with a limited number of nonscarring skin lesions in areas that are not cosmetically sensitive, observation is recommended. 1-3 For symptomatic patients with an extensive number of lesions, particularly those that may be scarring and/or in cosmetically sensitive areas, low-dose oral methotrexate therapy is considered first-line treatment.1-4 A methotrexate dose of 5 to 20 mg weekly can be effective in reducing the number and severity of lesions, with duration of treatment depending on clinical response.1,2 For patients who have contraindications to or who cannot tolerate oral methotrexate, phototherapy using psoralen plus UVA twice weekly for 6 to 8 weeks is another treatment option.1,2 Topical corticosteroids also can be used in children or for patients experiencing substantial pruritus.1,2,4 Oral or topical retinoids, topical carmustine or mechlorethamine, and brentuximab (an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody) are all alternative therapies that have shown some beneficial effects.1,2 In the event that any of the skin lesions do not spontaneously regress within a 3- to 12-week time frame, surgical excision or radiotherapy can be performed on those lesions.2

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL) is another CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with overlapping clinical and histopathological features of LyP. Recurrent crops of multiple lesions favor a diagnosis of LyP, whereas solitary lesions favor C-ALCL; however, multifocal C-ALCL cases may occur.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that characteristically presents in a patch, plaque, tumor progression. Although mycosis fungoides eventually may transform into a CD30+ lymphoma, our patient did not display the characteristic clinical progression to suggest this diagnosis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica also fall into the spectrum of clonal T-cell cutaneous disorders that more commonly affect the pediatric population. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta has a marked CD8+ lymphocyte infiltrate, whereas pityriasis lichenoides chronica has more CD4+ lymphocytes. These disorders typically do not stain positive for CD30.2

All patients with a diagnosis of LyP should maintain lifelong, regular, 6- to 12-month follow-up visits to monitor disease status and screen for any evidence of developing malignancy.1,2,6 A thorough review of clinical history, complete skin examination, and physical examination with a particular focus on detection of lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly should be included at every followup visit.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or weight loss are not typical features of LyP; therefore, patients who begin to develop these symptoms should be promptly evaluated for systemic lymphoma.1

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

At the time of the initial visit, a punch biopsy was performed on the posterior shoulder girdle. Histopathology revealed mild epidermal spongiosis and acanthosis with associated parakeratosis and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes consistent with pityriasis rosea (Figure 1). Two weeks after the biopsy, the patient returned for suture removal and to discuss the biopsy results. The patient reported more evolving lesions despite completing the prescribed course of dicloxacillin. At this time, physical examination revealed the persistence of several reddishbrown papules along with new nodular lesions on the arms and thighs, some with central ulceration and crusting (Figure 2). A second biopsy of a nodular lesion on the right distal forearm was performed at this visit along with a superficial tissue culture, which was negative for bacterial or fungal elements. The biopsy revealed an atypical CD30+ lymphoid proliferation (Figure 3). These cells were strongly PD-L1 positive and also positive for CD3, CD4, and granzyme-B. Ki67 showed a high proliferation rate, and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were positive. Given these histologic findings and the clinical context of rapidly evolving skin lesions from small papules to nodular skin tumors, a diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) was established.

Because of the notable pathologic discordance between the 2 biopsy specimens, re-evaluation of the initial specimen was requested. The initial biopsy was subsequently found to be CD30+ with an identical peak on gene rearrangement studies as the second biopsy, further validating the diagnosis of LyP (Figure 4). Our patient was offered low-dose methotrexate therapy but declined the treatment plan, as the skin lesions had begun to resolve.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with a characteristic recurrent and self-remitting disease course.1,2 Although it typically has a benign clinical course, it is histologically malignant and considered a low-grade variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. 2,3 The classic clinical presentation of LyP involves the presence of reddish-brown papules and nodules typically measuring less than 2.0 cm, which may show evidence of central ulceration, hemorrhage, necrosis, and/or crust formation.1-5 It is characteristic that a patient may present with these skin lesions in different stages of evolution and that biopsies of these lesions may reflect different histologic features depending on the age of the lesion, making a definitive diagnosis more difficult to obtain if not clinically correlated.1,2 Any part of the body may be involved; however, there appears to be a predilection for the trunk and extremities in most cases.1-3,5 The skin eruptions usually are asymptomatic, but pruritus is a commonly associated concern.1,2,4,5

Lymphomatoid papulosis can have a localized, clustered, or generalized distribution pattern and typically will spontaneously regress without treatment within 3 to 12 weeks of symptom onset.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis has a slight male predominance with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. It occurs most commonly between 35 and 45 years of age, though it can present at any age. The overall duration of the disease can range from months to decades.2,3 Lymphomatoid papulosis makes up approximately 15% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2,3 Although the overall prognosis is excellent, patients with LyP are at an increased risk of developing cutaneous or systemic lymphoma, most commonly mycosis fungoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, or Hodgkin lymphoma.1-3 This increased lifelong risk is the reason that patients with LyP must be followed long-term every 6 to 12 months for surveillance of emerging malignancy.1,2,6

The pathogenesis of LyP remains unknown. Some have hypothesized a possible viral trigger; however, there is insufficient data to support this theory.2,6 A diagnostic hallmark of LyP is its CD30 positivity, which is a known marker for T-cell activation.6 The spontaneous regression of skin lesions that is characteristic of LyP is believed to involve the interactions between CD30 and its ligand (CD30L), which may contribute to apoptosis of neoplastic T cells.2,3,6 With regards to the possible mechanisms contributing to tumor progression in LyP, a mutation in the transforming growth factor β receptor gene on CD30+ tumor cells within LyP lesions may allow for these cells to evade growth regulation and progress to lymphoma.2,6 A large percentage of LyP biopsy specimens show evidence of T-cell receptor gene monoclonal rearrangement, which can aid in establishing a diagnosis.1,2

The histologic features of LyP can vary greatly depending on the age of the lesion sampled.1,2 Histologic subtypes of LyP have been established, with type A being the most common (approximately 75% of cases), displaying a wedge-shaped infiltrate of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ T cells.1,2 Types B through E vary in histologic features, with the exception that all subtypes contain a CD30+ lymphocytic infiltrate.2,3

Treatment of LyP depends on the symptom/disease burden that the patient is experiencing. For patients with a limited number of nonscarring skin lesions in areas that are not cosmetically sensitive, observation is recommended. 1-3 For symptomatic patients with an extensive number of lesions, particularly those that may be scarring and/or in cosmetically sensitive areas, low-dose oral methotrexate therapy is considered first-line treatment.1-4 A methotrexate dose of 5 to 20 mg weekly can be effective in reducing the number and severity of lesions, with duration of treatment depending on clinical response.1,2 For patients who have contraindications to or who cannot tolerate oral methotrexate, phototherapy using psoralen plus UVA twice weekly for 6 to 8 weeks is another treatment option.1,2 Topical corticosteroids also can be used in children or for patients experiencing substantial pruritus.1,2,4 Oral or topical retinoids, topical carmustine or mechlorethamine, and brentuximab (an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody) are all alternative therapies that have shown some beneficial effects.1,2 In the event that any of the skin lesions do not spontaneously regress within a 3- to 12-week time frame, surgical excision or radiotherapy can be performed on those lesions.2

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL) is another CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder with overlapping clinical and histopathological features of LyP. Recurrent crops of multiple lesions favor a diagnosis of LyP, whereas solitary lesions favor C-ALCL; however, multifocal C-ALCL cases may occur.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that characteristically presents in a patch, plaque, tumor progression. Although mycosis fungoides eventually may transform into a CD30+ lymphoma, our patient did not display the characteristic clinical progression to suggest this diagnosis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica also fall into the spectrum of clonal T-cell cutaneous disorders that more commonly affect the pediatric population. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta has a marked CD8+ lymphocyte infiltrate, whereas pityriasis lichenoides chronica has more CD4+ lymphocytes. These disorders typically do not stain positive for CD30.2

All patients with a diagnosis of LyP should maintain lifelong, regular, 6- to 12-month follow-up visits to monitor disease status and screen for any evidence of developing malignancy.1,2,6 A thorough review of clinical history, complete skin examination, and physical examination with a particular focus on detection of lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly should be included at every followup visit.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or weight loss are not typical features of LyP; therefore, patients who begin to develop these symptoms should be promptly evaluated for systemic lymphoma.1

- Kadin ME. Lymphomatoid papulosis. UpToDate website. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lymphomatoid-papulosis

- Willemze R. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2017:2141-2143.

- Wiznia LE, Cohen JM, Beasley JM, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt4xt046c9.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.013

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Kunishige JH, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-581. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2008.03024.x

- Kadin ME. Lymphomatoid papulosis. UpToDate website. Accessed June 4, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lymphomatoid-papulosis

- Willemze R. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2017:2141-2143.

- Wiznia LE, Cohen JM, Beasley JM, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt4xt046c9.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.013

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Kunishige JH, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-581. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2008.03024.x

A 37-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a pruritic erythematous eruption involving the trunk, axillae, and proximal extremities of 10 days’ duration. Her medical history was notable only for eczema, and she denied taking any medications. Physical examination revealed scattered erythematous papules and crusts involving the trunk bilaterally and the extremities. We initially made a clinical diagnosis of bullous impetigo, and the patient was prescribed mupirocin ointment and dicloxacillin. At 1-week follow-up, the patient reported persistent skin lesions that were evolving despite therapy. Physical examination at this visit revealed an evolving eruption of multiple reddish-brown scaly papules involving the axillae, arms, forearms, and thighs, as depicted here.

Expanding Verrucous Plaque on the Face

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

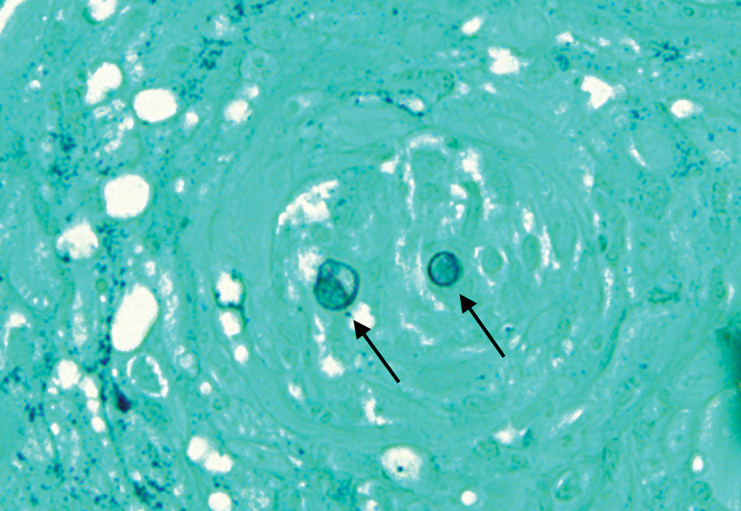

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

A 69-year-old man presented with a slowly expanding, verrucous plaque on the left side of the upper cutaneous lip of 4 months’ duration. The lesion reportedly began as an abscess and had undergone incision and drainage followed by multiple courses of oral antibiotics that were unsuccessful prior to presentation to our clinic. The patient’s hobbies included gardening near his summer home in the mountains of western North Carolina, where he resided when the lesion appeared. Physical examination revealed an approximately 6×4-cm verrucous plaque with central ulceration on the left side of the upper cutaneous and vermilion lip extending to the nasolabial fold. A review of systems was negative for any systemic symptoms. Routine laboratory tests and computed tomography of the head and neck were normal.