User login

Expanding Verrucous Plaque on the Face

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

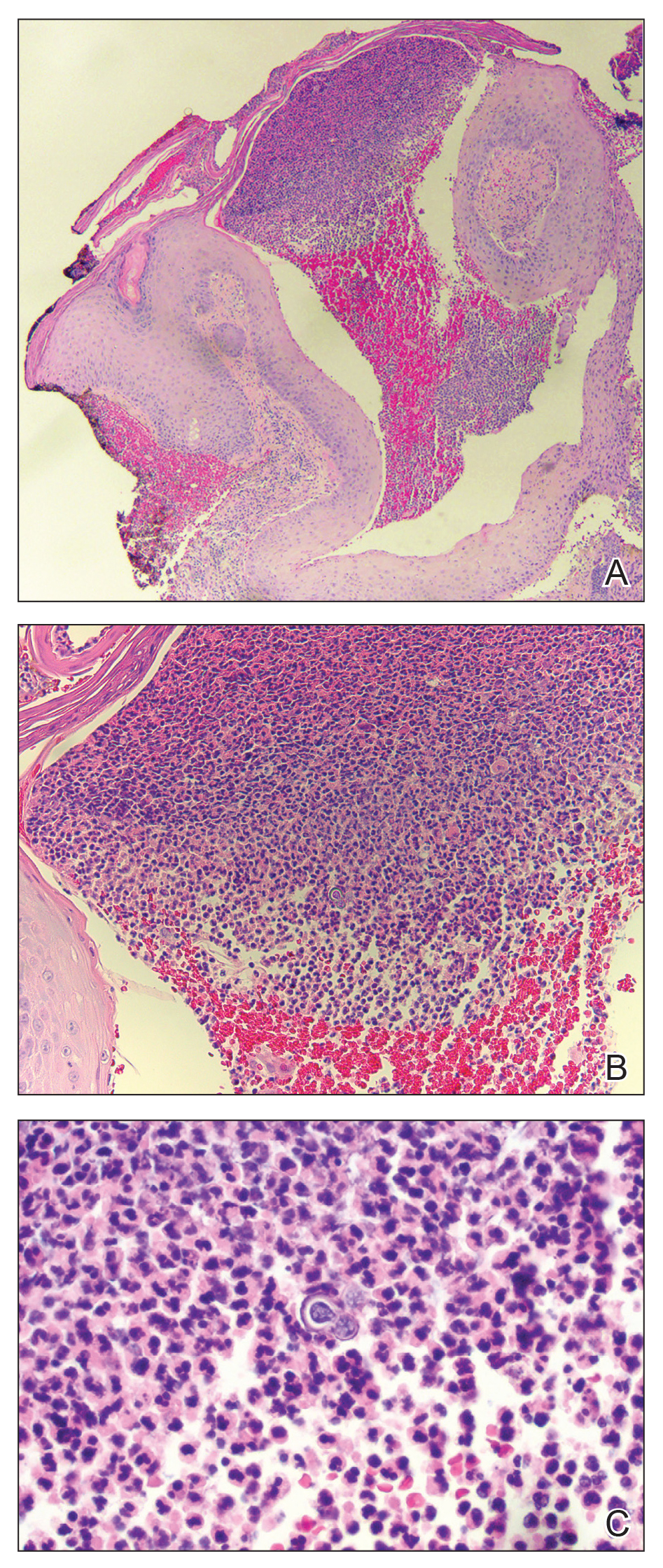

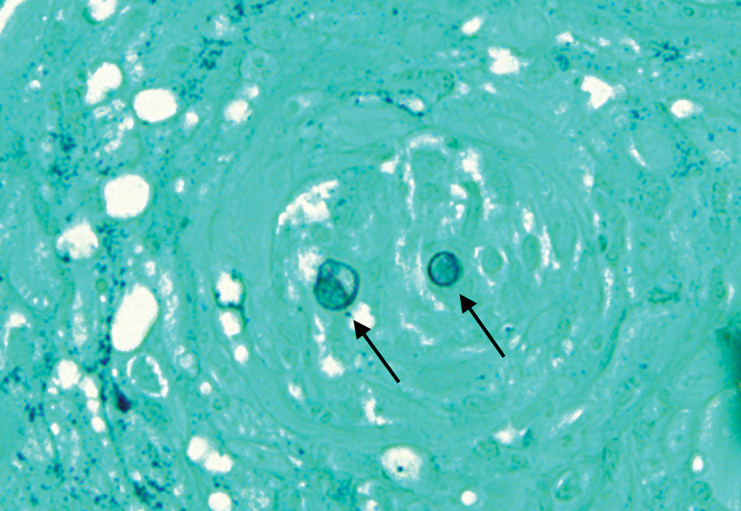

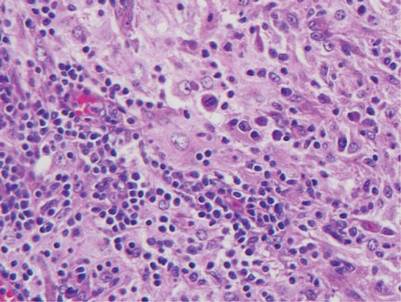

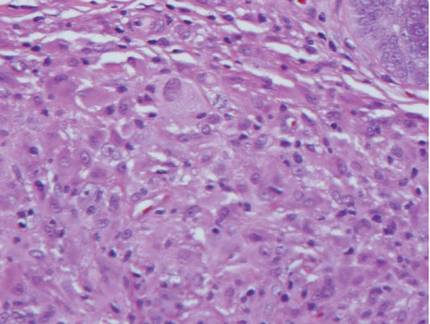

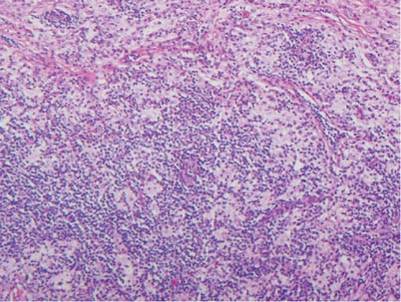

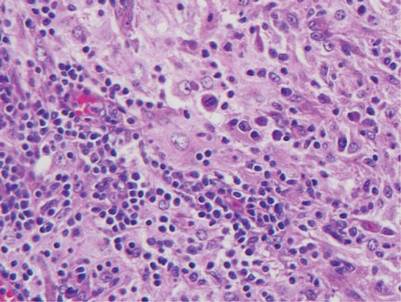

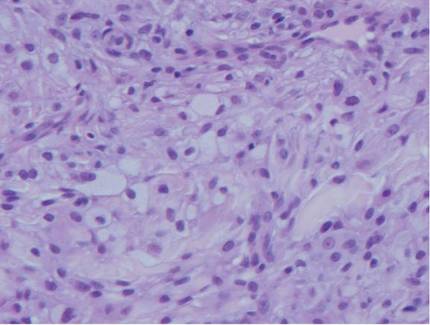

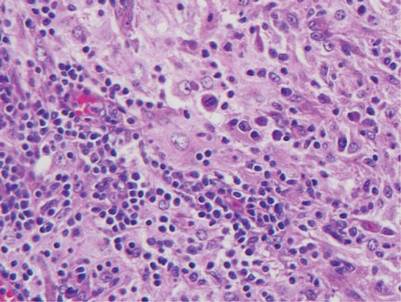

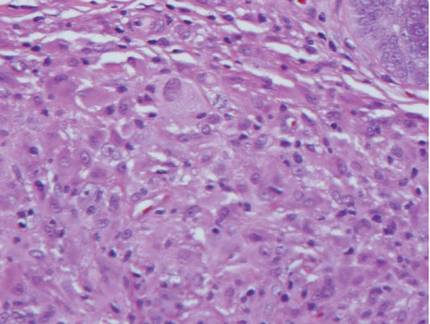

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

A 69-year-old man presented with a slowly expanding, verrucous plaque on the left side of the upper cutaneous lip of 4 months’ duration. The lesion reportedly began as an abscess and had undergone incision and drainage followed by multiple courses of oral antibiotics that were unsuccessful prior to presentation to our clinic. The patient’s hobbies included gardening near his summer home in the mountains of western North Carolina, where he resided when the lesion appeared. Physical examination revealed an approximately 6×4-cm verrucous plaque with central ulceration on the left side of the upper cutaneous and vermilion lip extending to the nasolabial fold. A review of systems was negative for any systemic symptoms. Routine laboratory tests and computed tomography of the head and neck were normal.

Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

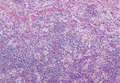

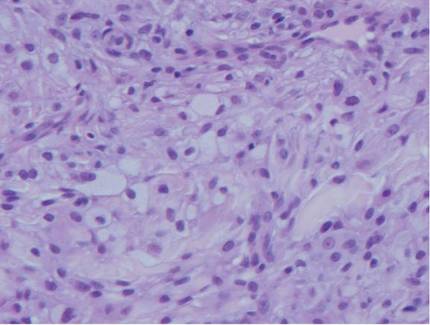

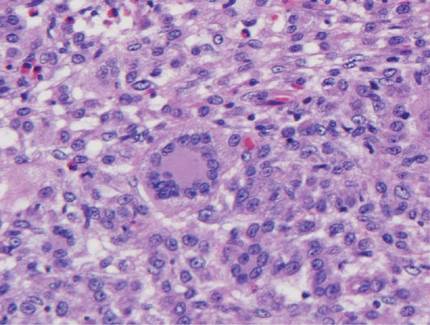

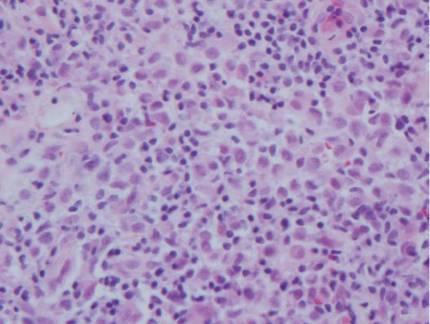

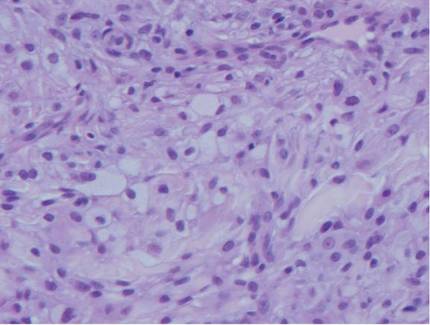

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|  |

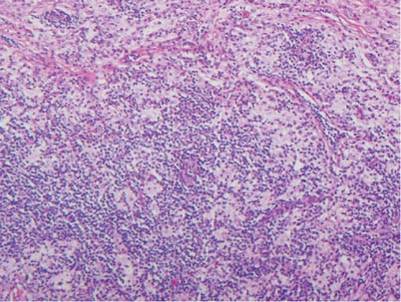

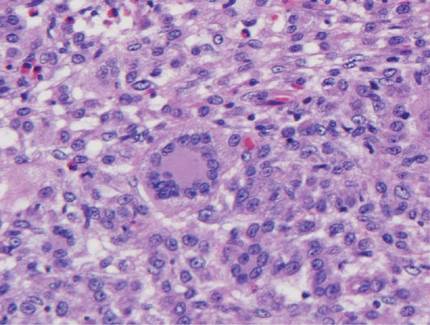

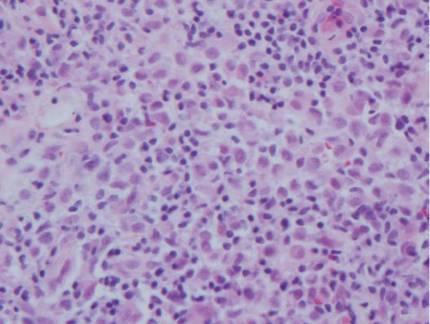

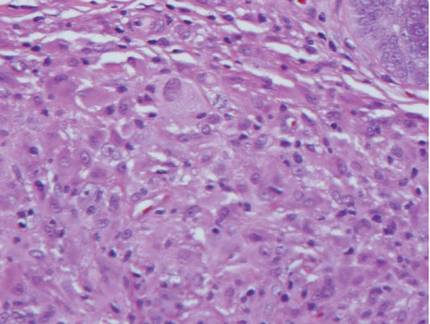

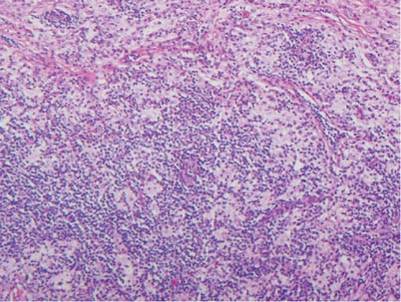

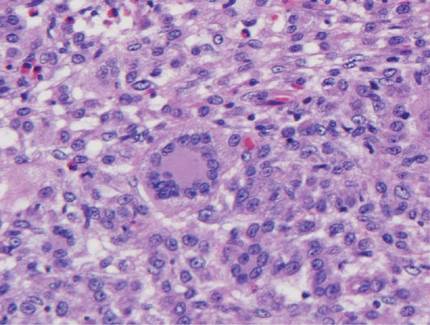

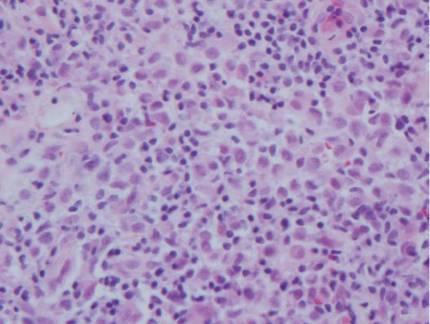

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|  | ||

|  |

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|  |

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|  | ||

|  |

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|  |

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|  | ||

|  |

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.