User login

Bleeding Nodule on the Lip

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

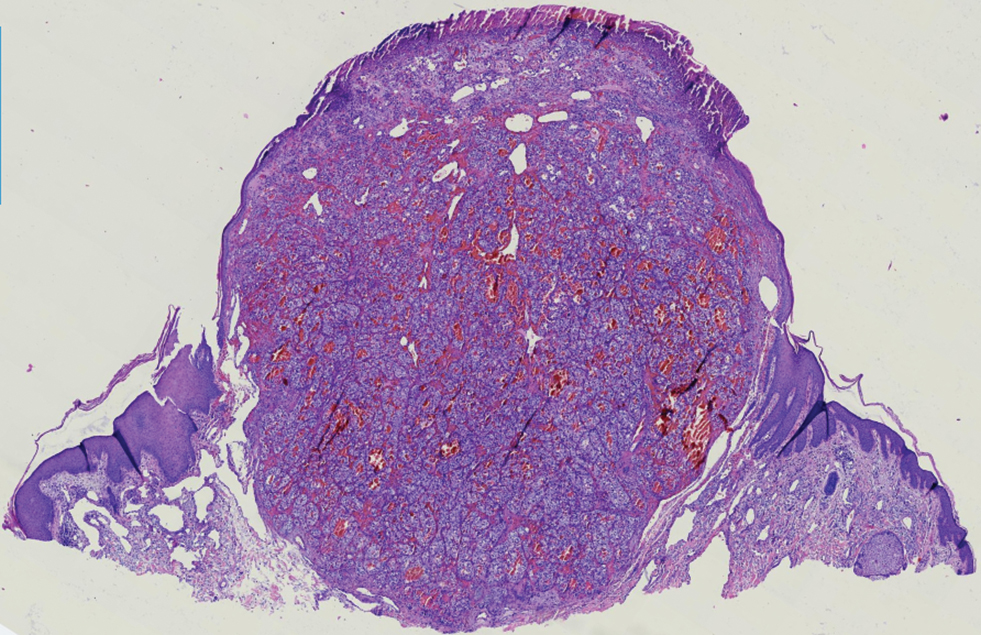

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a common genitourinary system malignancy with incidence peaking between 50 and 70 years of age and a male predominance.1 The clear cell variant is the most common subtype of RCC, accounting for 70% to 75% of all cases. It is known to be a highly aggressive malignancy that frequently metastasizes to the lungs, lymphatics, bones, liver, and brain.2,3 Approximately 20% to 50% of patients with RCC eventually will develop metastasis after nephrectomy.4 Survival with metastatic RCC to any site typically is in the range of 10 to 22 months.5,6 Cutaneous metastases of RCC rarely have been reported in the literature (3%–6% of cases7) and most commonly are found on the scalp, followed by the chest or abdomen. 8 Cutaneous metastases generally are regarded as a late manifestation of the disease with a very poor prognosis. 9 It is unusual to identify cutaneous RCC metastasis without known RCC or other symptoms consistent with advanced RCC, such as hematuria or abdominal/flank pain. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for an estimated 6% to 7% of all cutaneous metastatic lesions.10 Cutaneous metastatic lesions of RCC often are solitary and grow rapidly, with the clinical appearance of an erythematous or violaceous, nodular, highly vascular, and often hemorrhagic growth.9,11,12

Following the histologic diagnosis of metastatic clear cell RCC, our patient was referred to medical oncology for further workup. Magnetic resonance imaging and a positron emission tomography scan demonstrated widespread disease with a 7-cm left renal mass, liver and lung metastases, and bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was started on combination immunotherapy as a palliative treatment given the widespread disease.

Histologically, clear cell RCC is characterized by lipid and glycogen-rich cells with ample cytoplasm and a well-developed vascular network, which often is thin walled with a chicken wire–like architecture. Metastatic clear cell RCC tumor cells may form glandular, acinar, or papillary structures with variable lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates and abundant capillary formation. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells should demonstrate positivity for paired box gene 8, PAX8, and RCC marker antigen.13 Vimentin and carcinoembryonic antigen may be utilized to distinguish from hidradenoma as carcinoembryonic antigen will be positive in hidradenoma and vimentin will be negative.14 Renal cell carcinoma also has a common molecular signature of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene inactivation as well as upregulation of hypoxia inducible factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.15

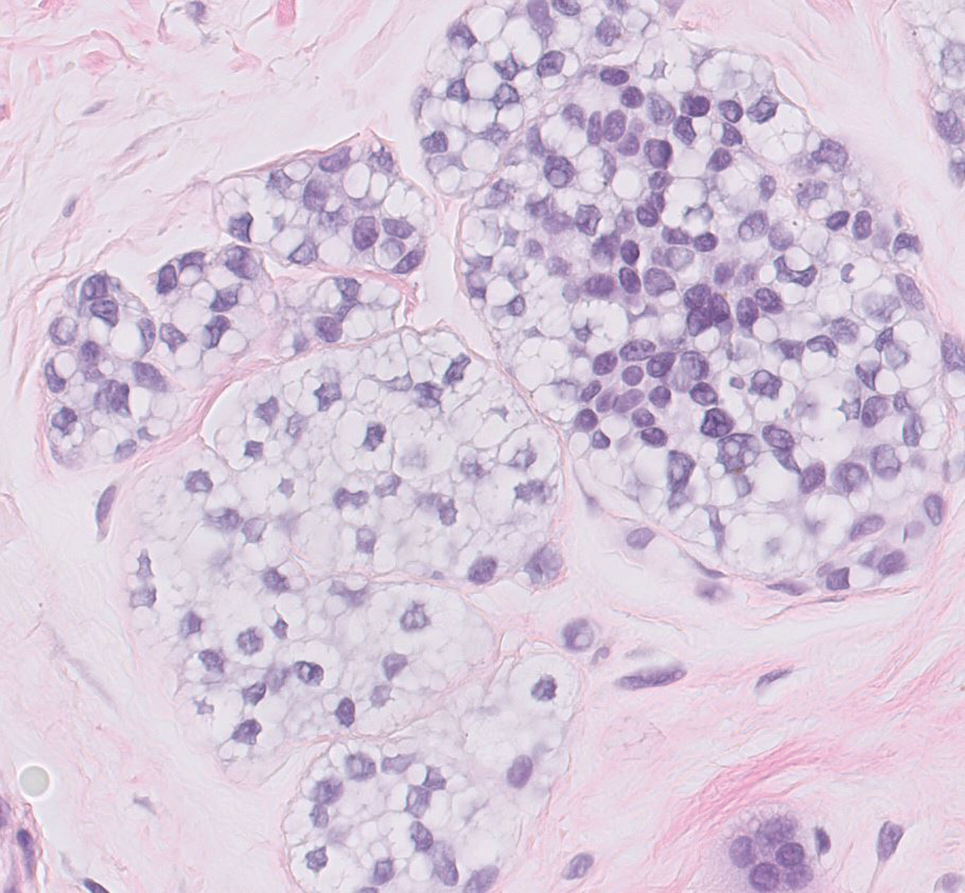

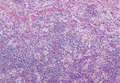

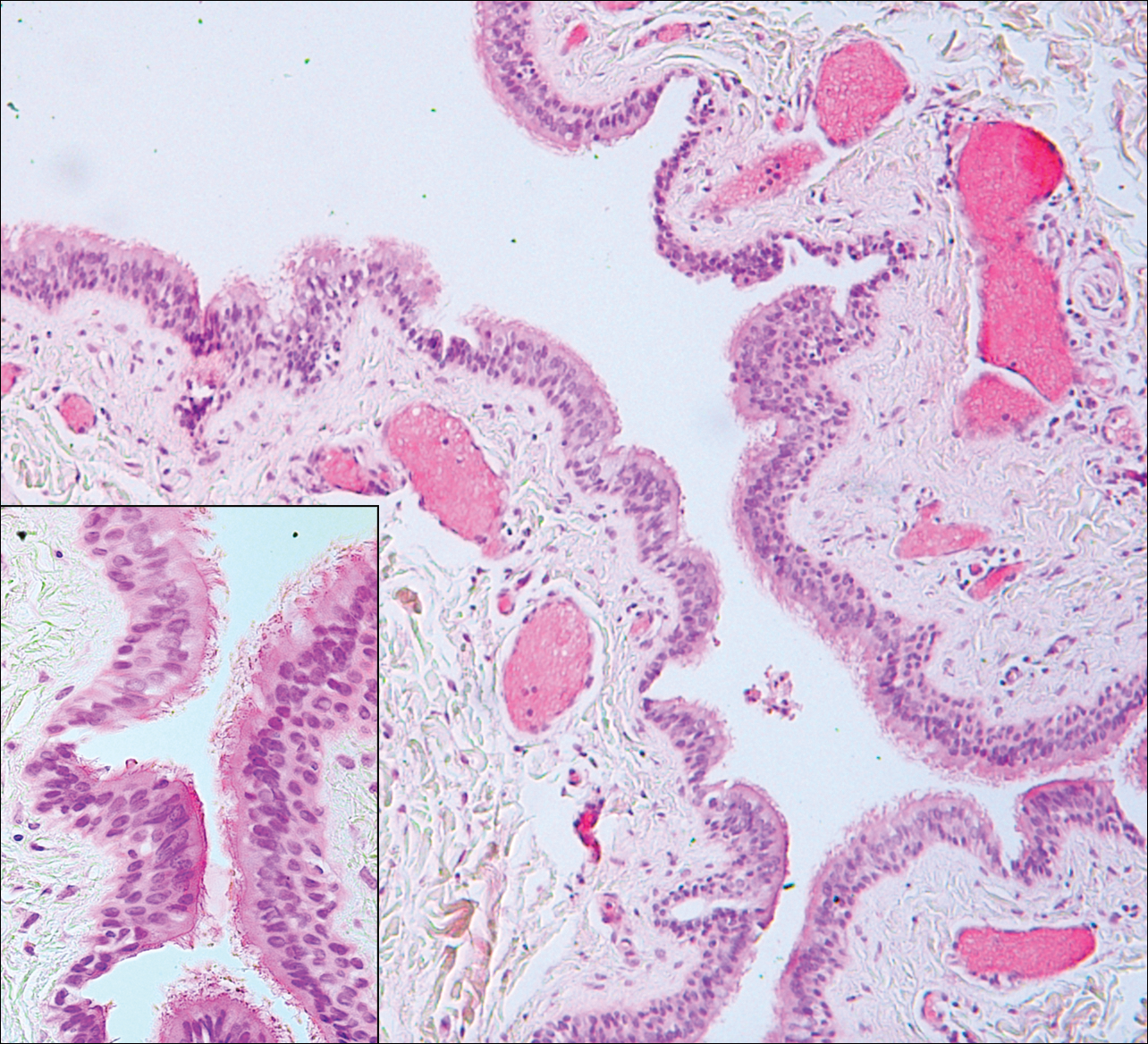

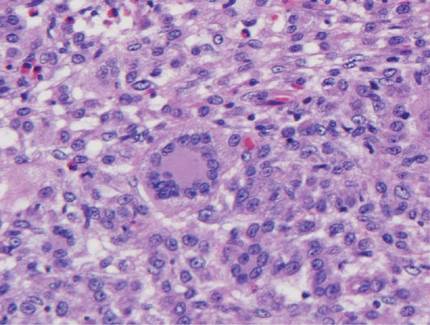

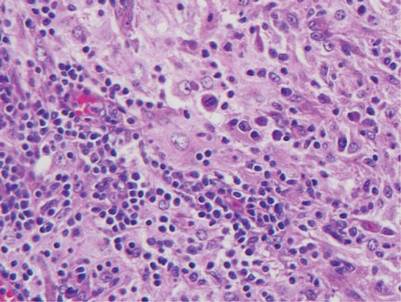

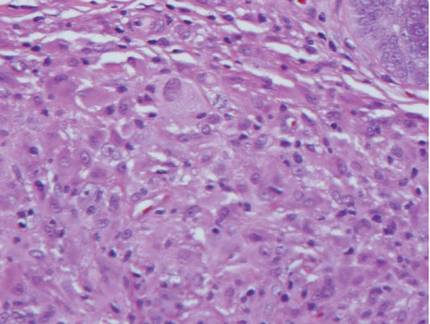

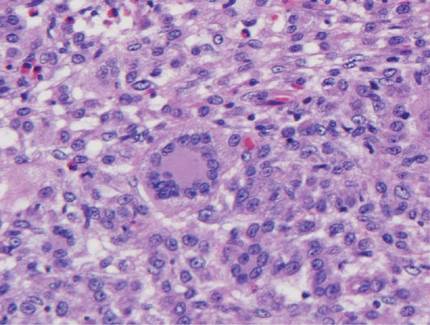

Balloon cell nevi often clinically present in young patients as bicolored nevi that sometimes are polypoid or verrucous in appearance with central yellow globules surrounded by a peripheral reticular pattern on dermoscopy. Histologically, balloon cell nevi are characterized by large cells with small, round, centrally located basophilic nuclei and clear foamy cytoplasm (Figure 1), which are thought to be formed by progressive vacuolization of melanocytes due to the enlargement and disintegration of melanosomes. This ballooning change reflects an seen in malignant melanoma, in which case nuclear pleomorphism, atypia, and increased mitotic activity also are observed. The prominent vascular network characteristic of RCC typically is not present.16

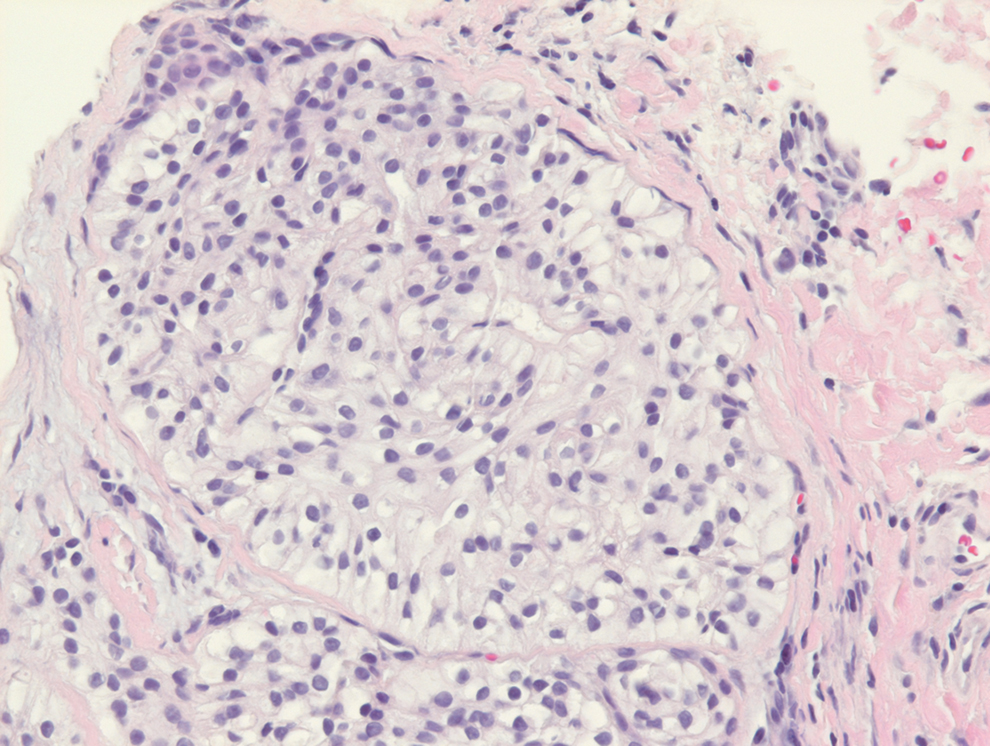

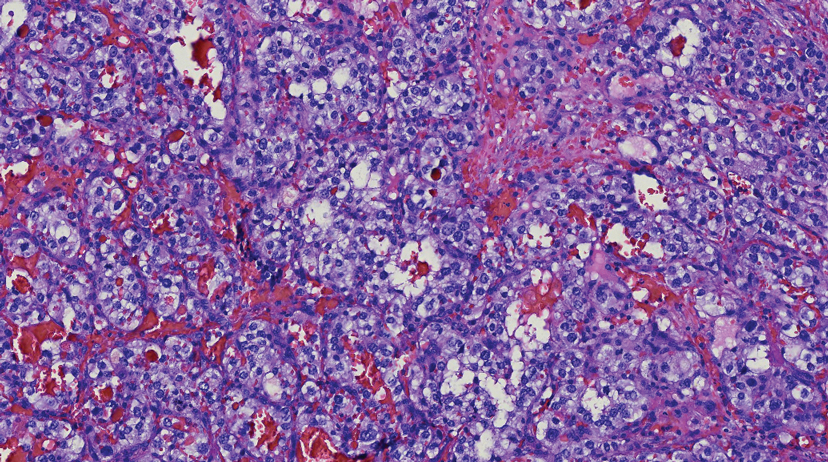

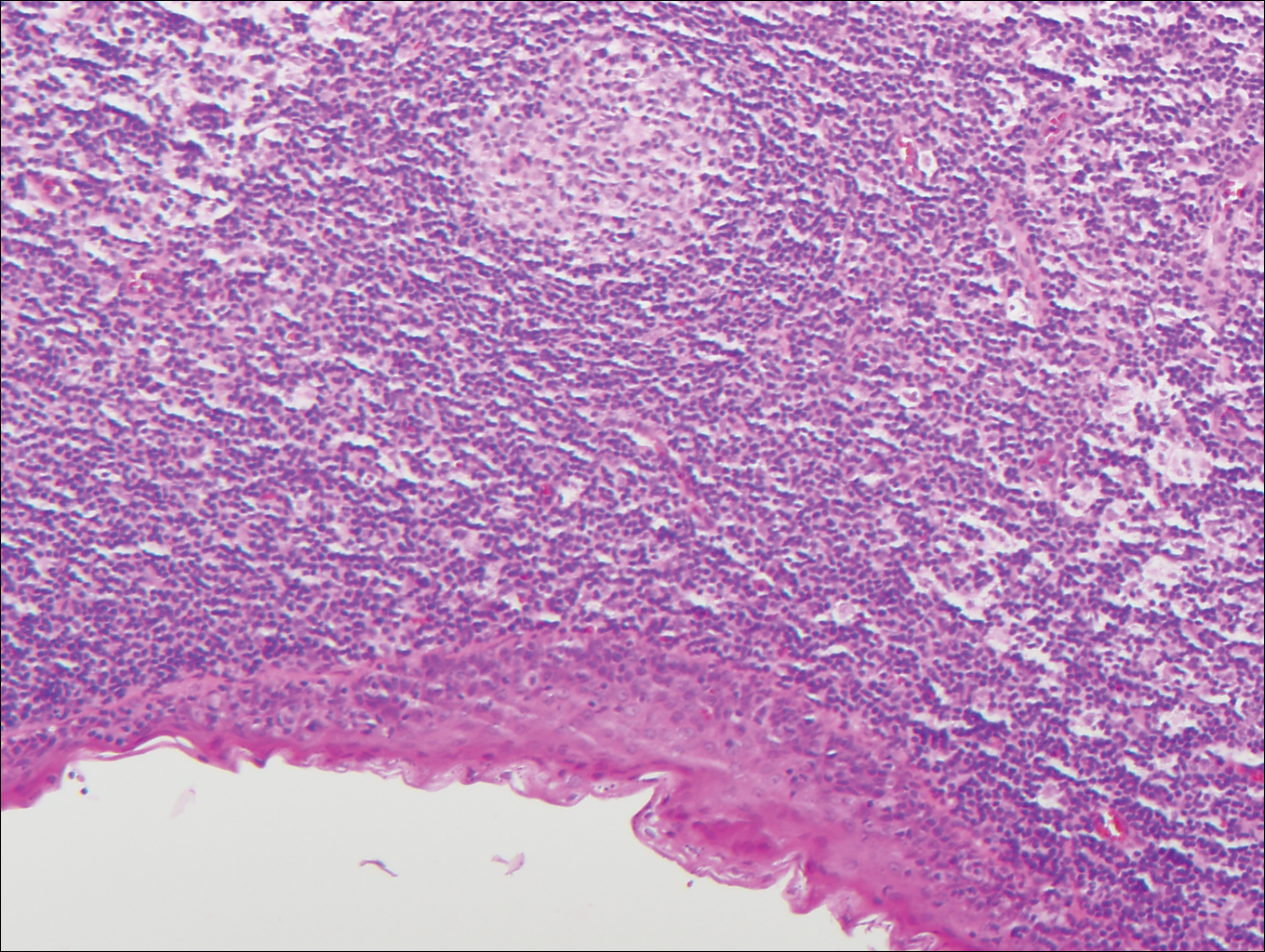

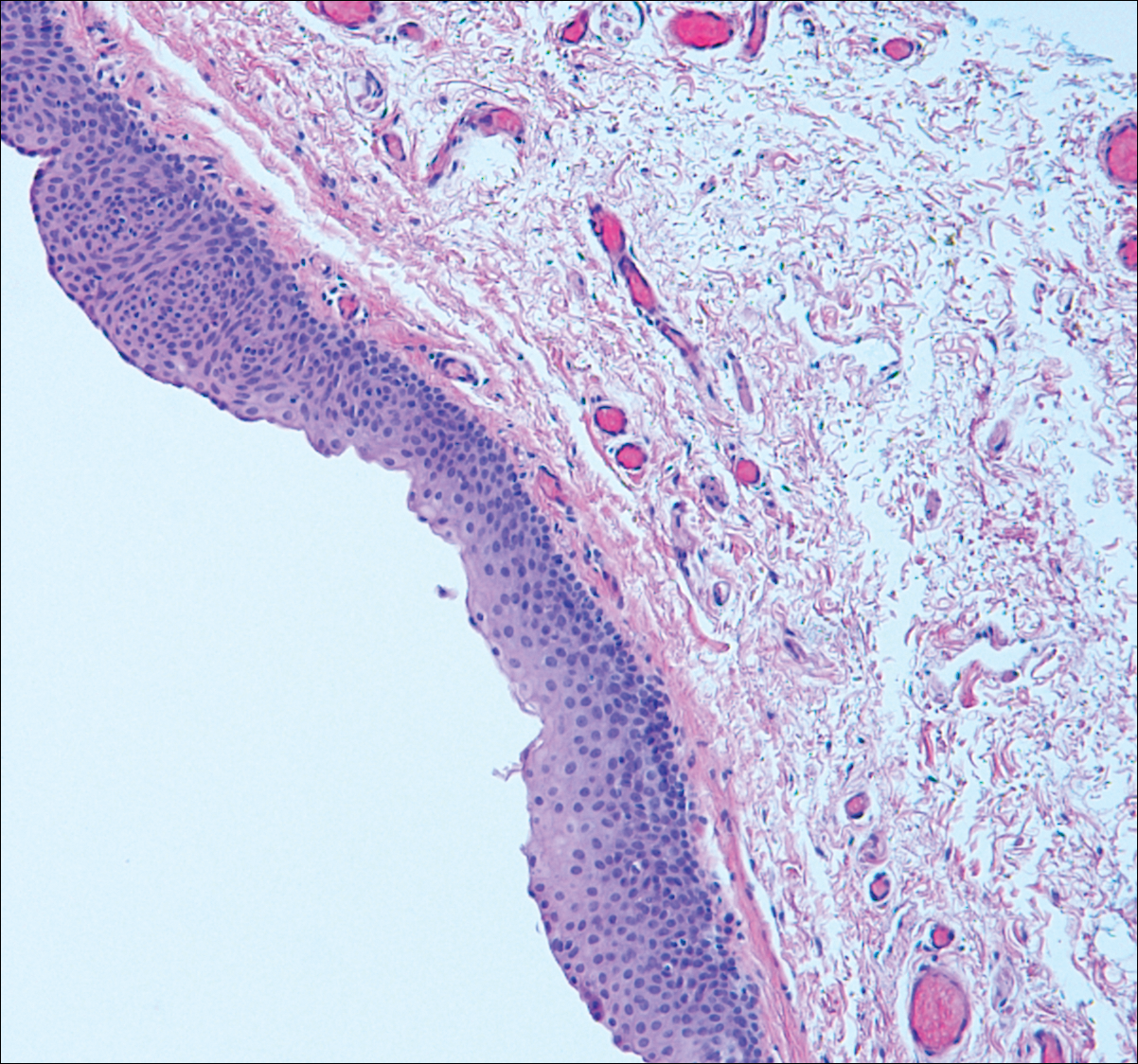

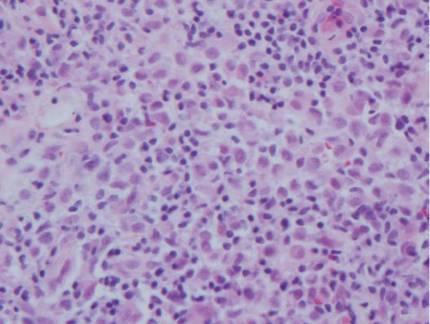

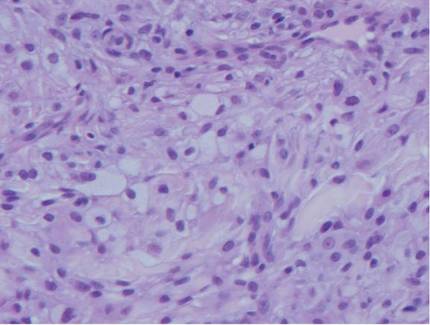

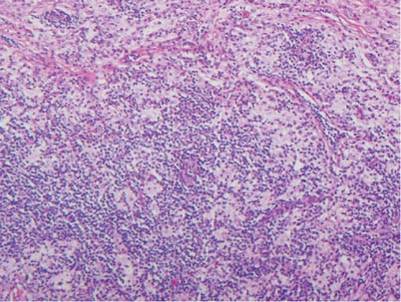

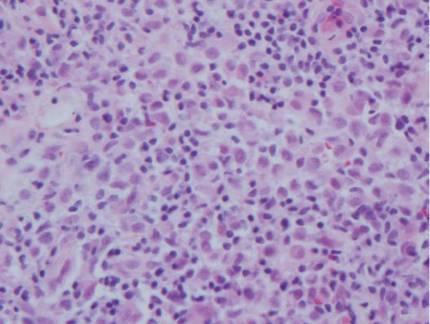

Clear cell hidradenomas are benign skin appendage tumors that often present as small, firm, solitary dermal nodules that may extend into the subcutaneous fat. They have a predilection for the head, face, and arms and demonstrate 2 predominant cell types, including a polyhedral cell with a rounded nucleus and slightly basophilic cytoplasm as well as a round cell with clear cytoplasm and bland nuclei (Figure 2). The latter cell type is less common, representing the predominant cell type in less than one-third of hidradenomas, and can present a diagnostic quandary based on histologic similarity to other clear cell neoplasms. The clear cells contain glycogen but no lipid. Ductlike structures often are present, and the intervening stroma varies from delicate vascularized cords of fibrous tissue to dense hyalinized collagen. Immunohistochemistry may be required for definitive diagnosis, and clear cell hidradenomas should react with monoclonal antibodies that label both eccrine and apocrine secretory elements, such as cytokeratins 6/18, 7, and 8/18.17

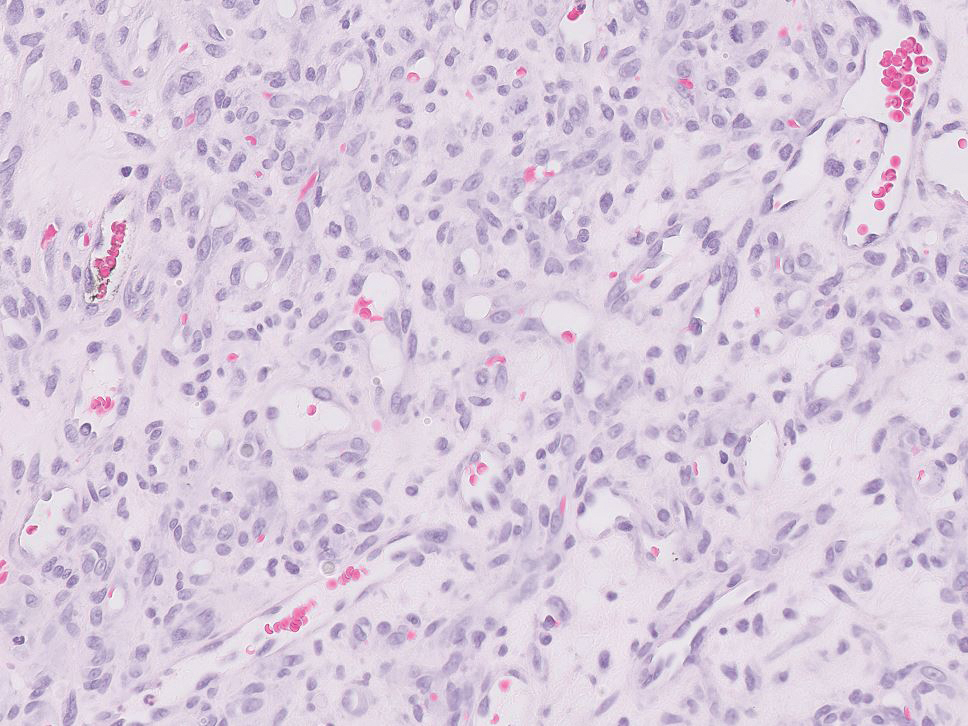

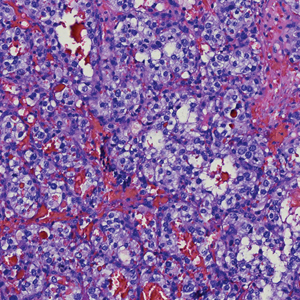

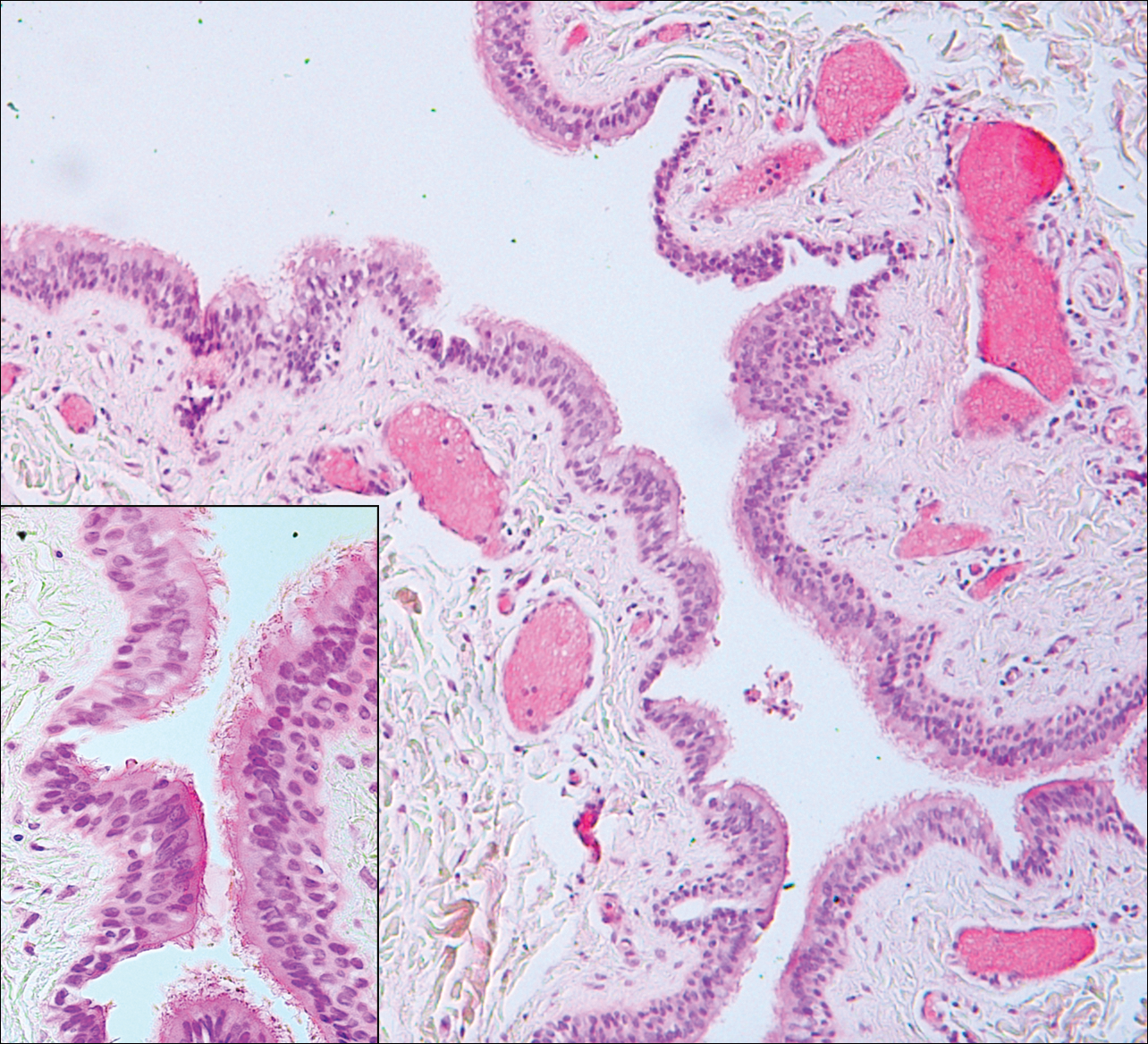

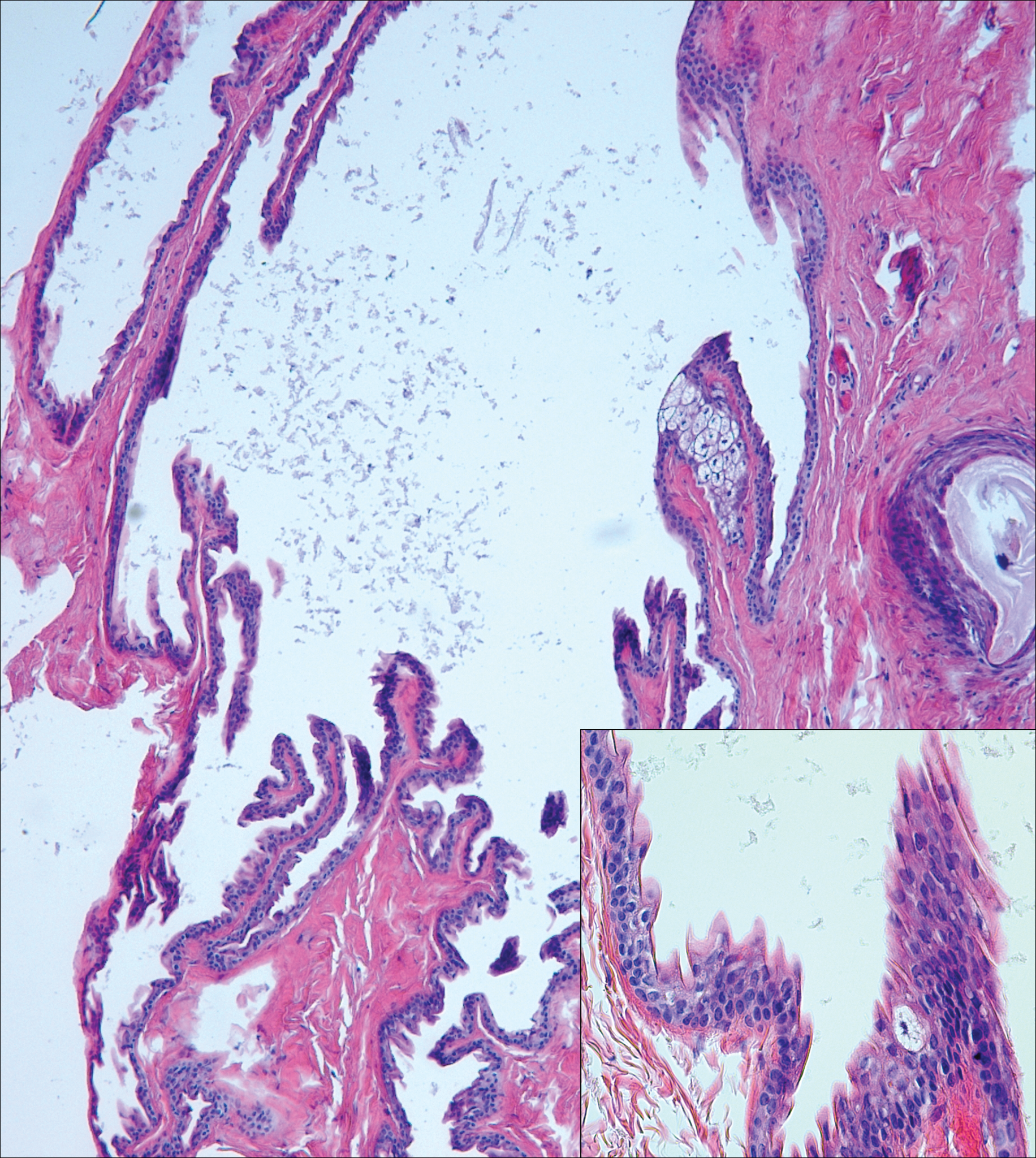

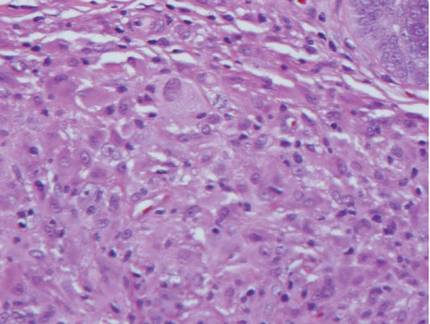

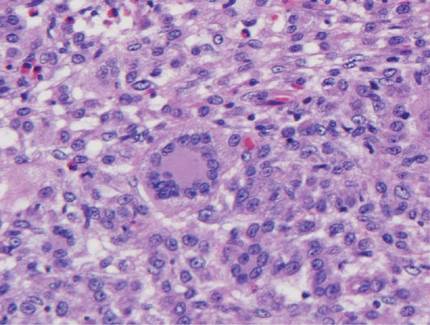

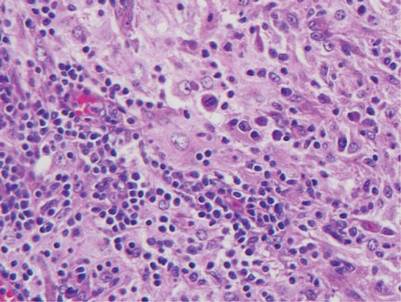

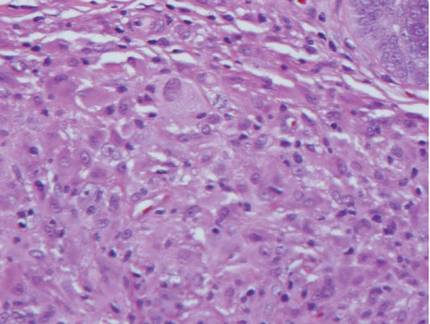

Pyogenic granulomas (also referred to as lobular capillary hemangiomas) are common and present clinically as rapidly growing, polypoid, red masses surrounded by a thickened epidermis that often are found on the fingers or lips. This entity is benign and often regresses spontaneously. Histologically, pyogenic granulomas are characterized by a lobular pattern of vascular proliferation associated with edema and inflammation resembling granulation tissue, with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis at the edges of the lesion (Figure 3).18

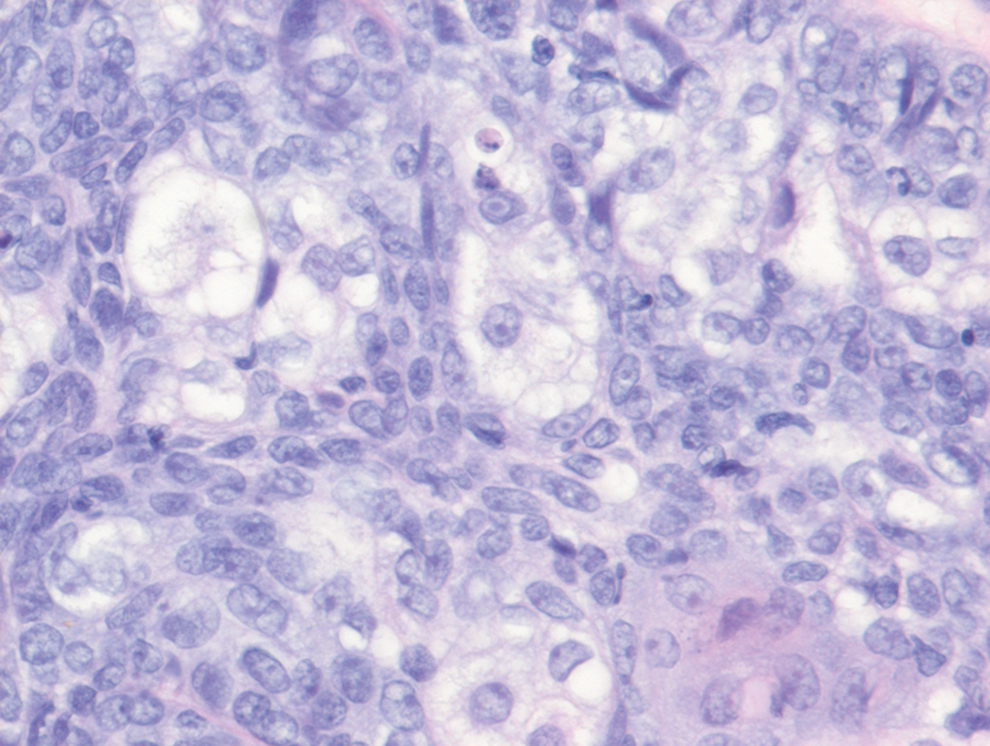

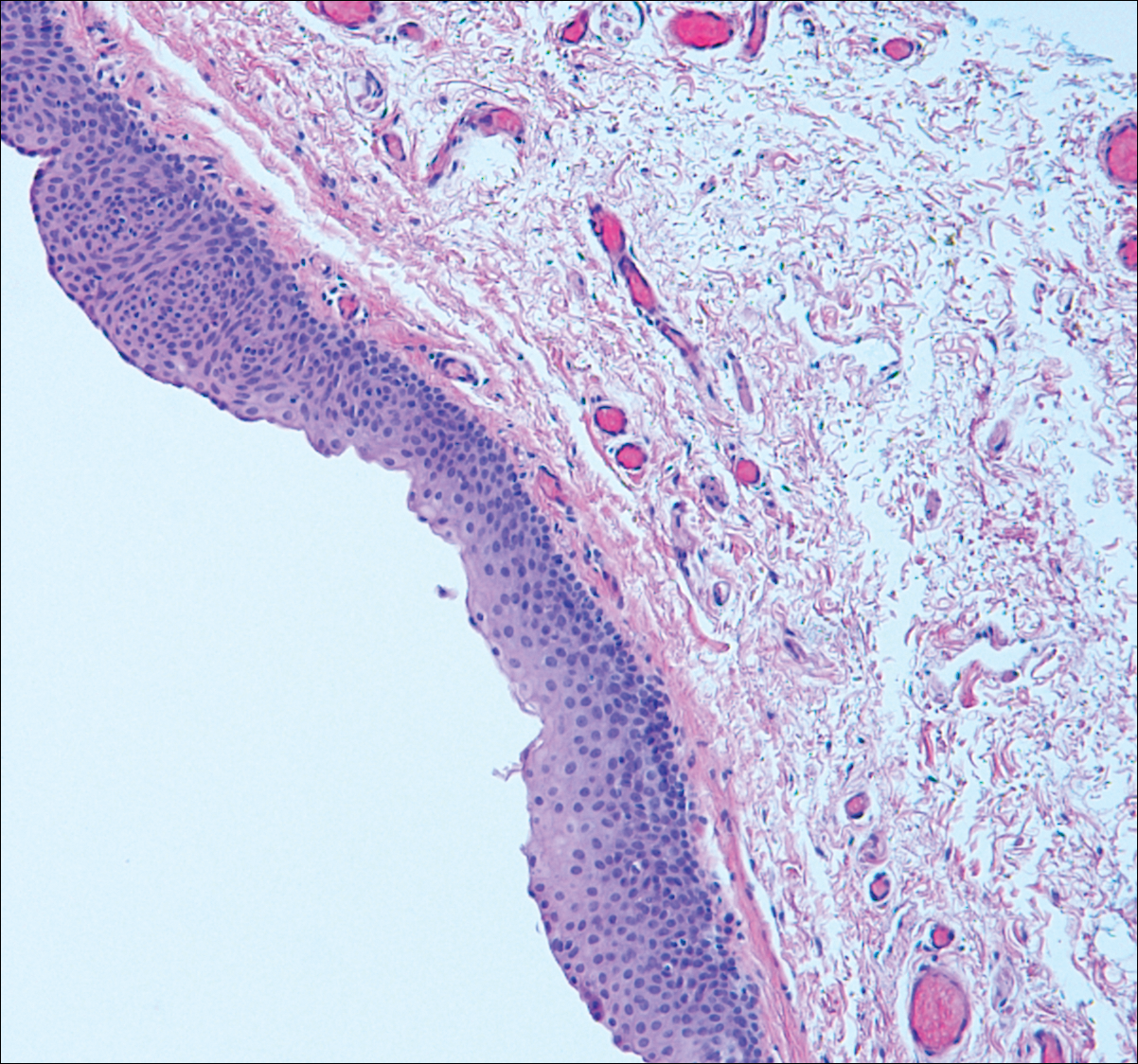

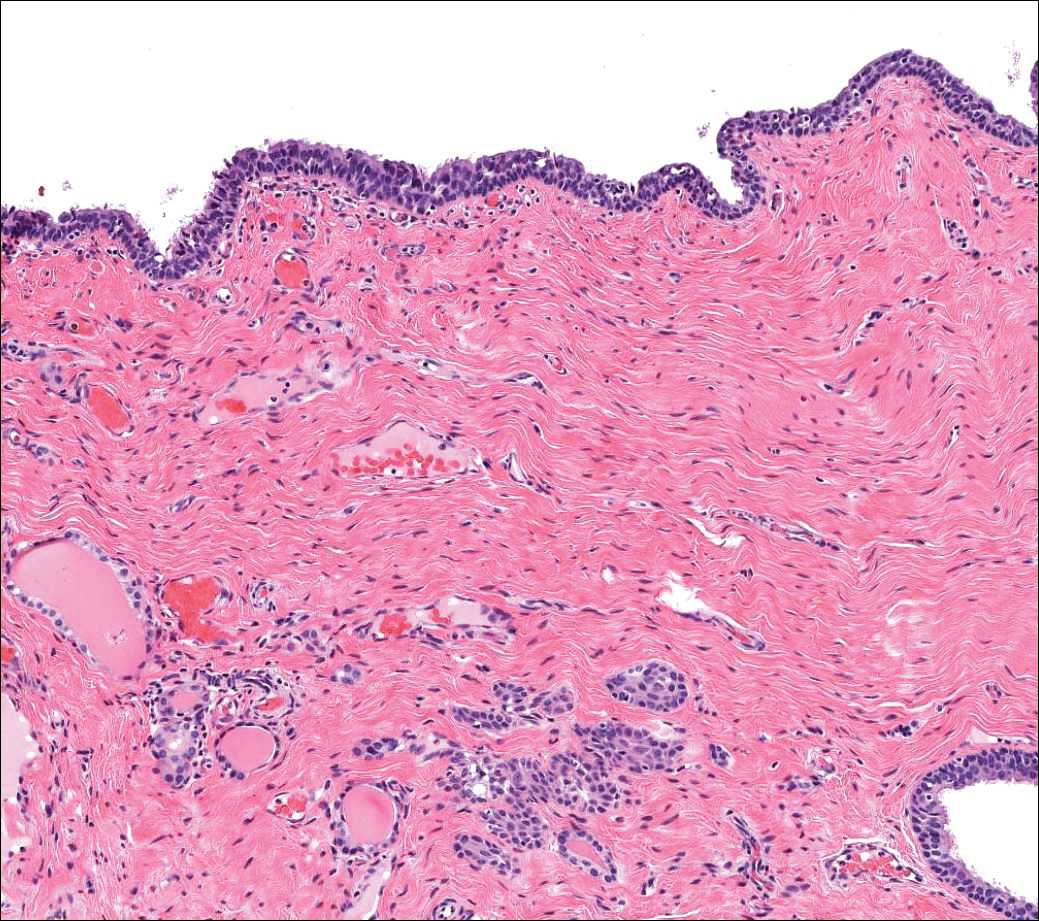

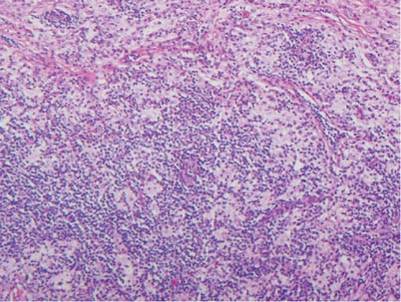

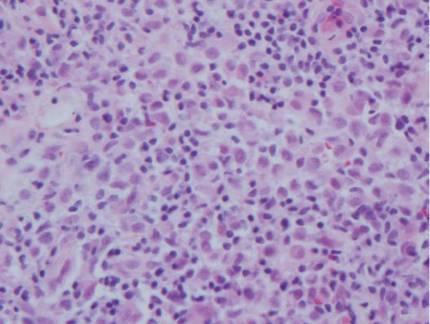

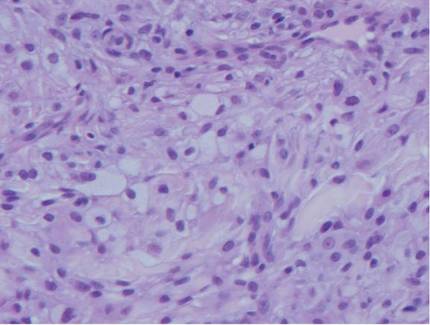

Sebaceous carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from the cells of the sebaceous glands and occurring most commonly in the periorbital area. This neoplasm most often affects older adults, with a mean age at diagnosis of 63 to 77 years. It commonly presents as a solitary nodule with yellowish discoloration and madarosis, which is a key distinguishing feature to differentiate this entity from a chalazion or hordeolum. Histologically, sebaceous carcinoma is a dermal-based infiltrative, nodular tumor with varying degrees of clear cell changes—well-differentiated tumors show more clear cell change as compared to more poorly differentiated variants—along with basaloid or squamous features and abundant mitotic activity (Figure 4), which may be useful in distinguishing it from the other entities in the clear cell neoplasm differential.19-22

- Alves de Paula T, Lopes da Silva P, Sueth Berriel LG. Renal cell carcinoma with cutaneous metastasis: case report. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32:213-215.

- Amaadour L, Atreche L, Azegrar M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J Cancer Ther. 2017;8:603-607.

- Weiss L, Harlos JP, Torhorst J, et al. Metastatic patterns of renal carcinoma: an analysis of 687 necropsies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:605-612.

- Flamigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:385-390.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwarz LH, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:453-463.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor–targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5694-5799.

- Smyth LG, Rowan GC, David MQ. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as an ominous metachronous scalp metastasis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:E64-E66.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Koga S, Tsuda S, Nishikido M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the skin. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:1939-1940.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a metaanalysis of the data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Amano Y, Ohni S, Ishige T, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis from a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with an eosinophilic cell component to the submandibular region. J Nihon Univ Med Assoc. 2015;74:73-77.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Sangoi AR, Karamchandani J, Kim J, et al. The use of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a review of PAX-8, PAX-2, hKIM-1, RCCma, and CD10. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:377-393.

- Velez MJ, Thomas CL, Stratton J, et al. The utility of using immunohistochemistry in the differentiation of metastatic, cutaneous clear cell renal cell carcinoma and clear cell hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:612-615.

- Nezami BG, MacLennan G. Clear cell. PathologyOutlines website. Published April 20, 2021. Updated March 2, 2022. Accessed April 22, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/kidneytumormalignantrccclear.html

- Dhaille F, Courville P, Joly P, et al. Balloon cell nevus: histologic and dermoscopic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:E55-E56.

- Volmar KE, Cummings TJ, Wang WH, et al. Clear cell hidradenoma: a mimic of metastatic clear cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:E113-E116.

- Hale CS. Capillary/pyogenic granuloma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 1, 2012. Updated March 10, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticpyogenicgranuloma.html

- Zada S, Lee BA. Sebaceous carcinoma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 11, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticsebaceouscarcinoma.html

- Kahana A, Pribila, JT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

- Wick MR. Cutaneous tumors and pseudotumors of the head and neck. In: Gnepp DR, ed. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2009:975-1068.

- Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma. In: Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al, eds. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:174-179.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a common genitourinary system malignancy with incidence peaking between 50 and 70 years of age and a male predominance.1 The clear cell variant is the most common subtype of RCC, accounting for 70% to 75% of all cases. It is known to be a highly aggressive malignancy that frequently metastasizes to the lungs, lymphatics, bones, liver, and brain.2,3 Approximately 20% to 50% of patients with RCC eventually will develop metastasis after nephrectomy.4 Survival with metastatic RCC to any site typically is in the range of 10 to 22 months.5,6 Cutaneous metastases of RCC rarely have been reported in the literature (3%–6% of cases7) and most commonly are found on the scalp, followed by the chest or abdomen. 8 Cutaneous metastases generally are regarded as a late manifestation of the disease with a very poor prognosis. 9 It is unusual to identify cutaneous RCC metastasis without known RCC or other symptoms consistent with advanced RCC, such as hematuria or abdominal/flank pain. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for an estimated 6% to 7% of all cutaneous metastatic lesions.10 Cutaneous metastatic lesions of RCC often are solitary and grow rapidly, with the clinical appearance of an erythematous or violaceous, nodular, highly vascular, and often hemorrhagic growth.9,11,12

Following the histologic diagnosis of metastatic clear cell RCC, our patient was referred to medical oncology for further workup. Magnetic resonance imaging and a positron emission tomography scan demonstrated widespread disease with a 7-cm left renal mass, liver and lung metastases, and bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was started on combination immunotherapy as a palliative treatment given the widespread disease.

Histologically, clear cell RCC is characterized by lipid and glycogen-rich cells with ample cytoplasm and a well-developed vascular network, which often is thin walled with a chicken wire–like architecture. Metastatic clear cell RCC tumor cells may form glandular, acinar, or papillary structures with variable lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates and abundant capillary formation. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells should demonstrate positivity for paired box gene 8, PAX8, and RCC marker antigen.13 Vimentin and carcinoembryonic antigen may be utilized to distinguish from hidradenoma as carcinoembryonic antigen will be positive in hidradenoma and vimentin will be negative.14 Renal cell carcinoma also has a common molecular signature of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene inactivation as well as upregulation of hypoxia inducible factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.15

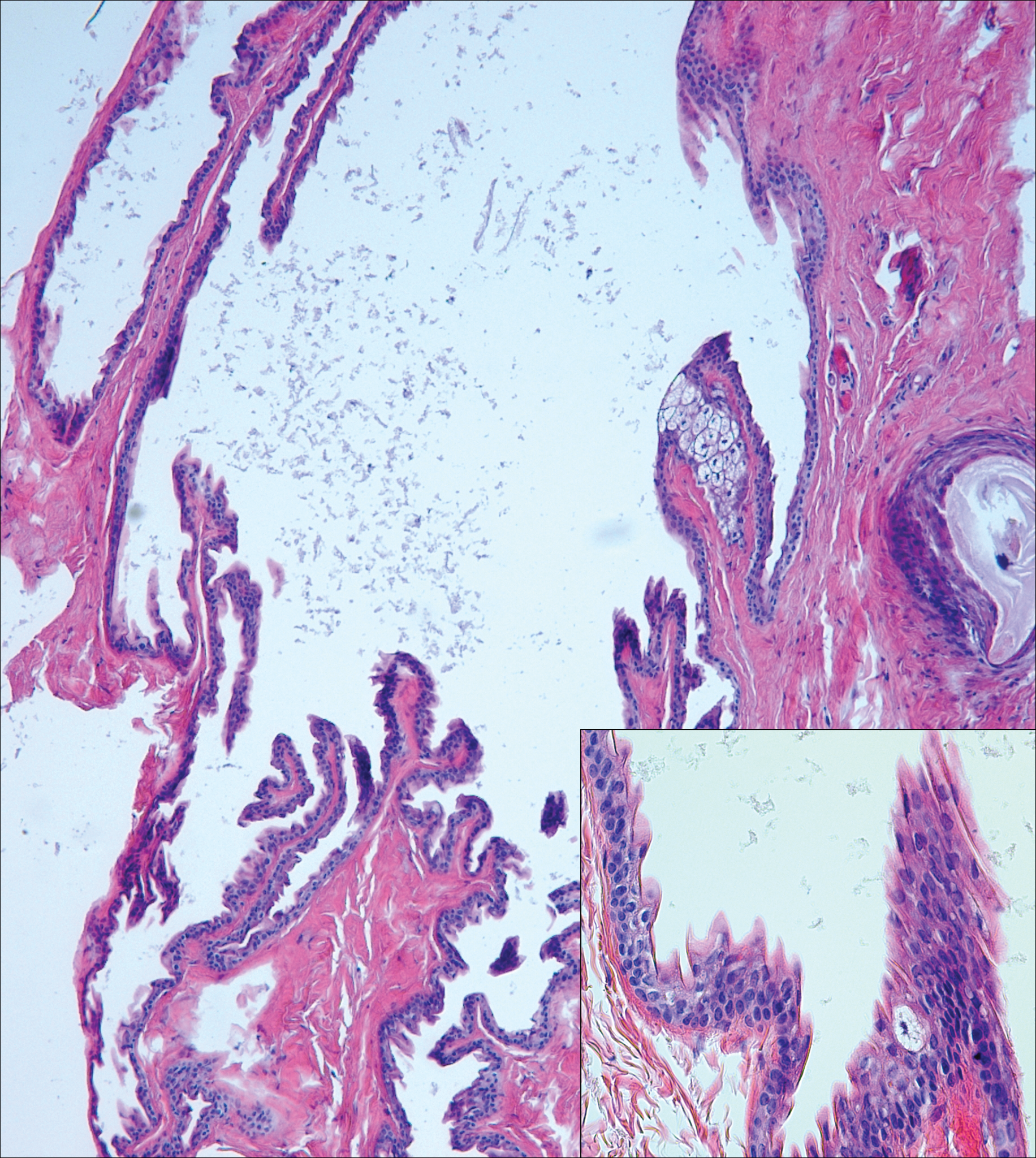

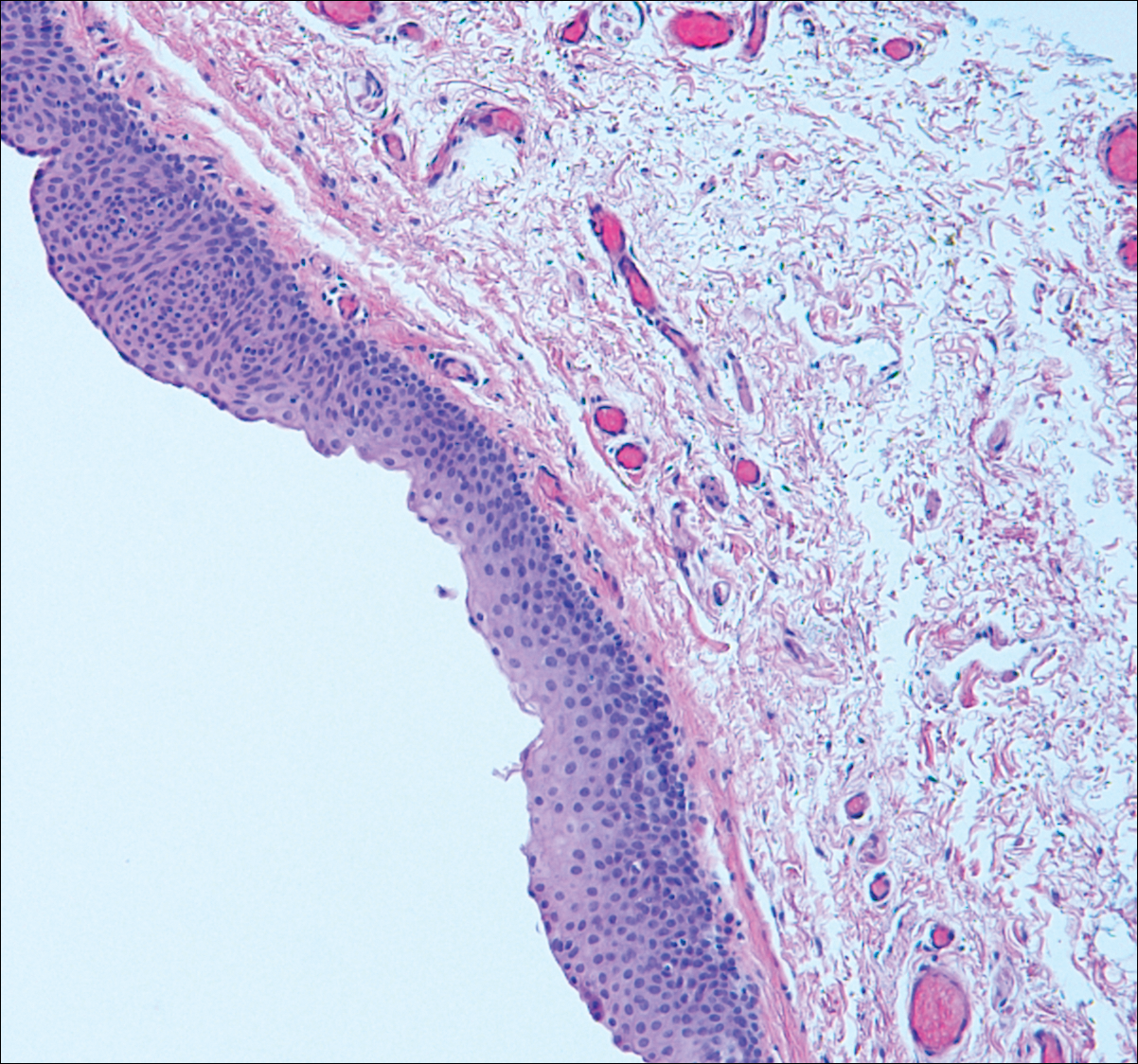

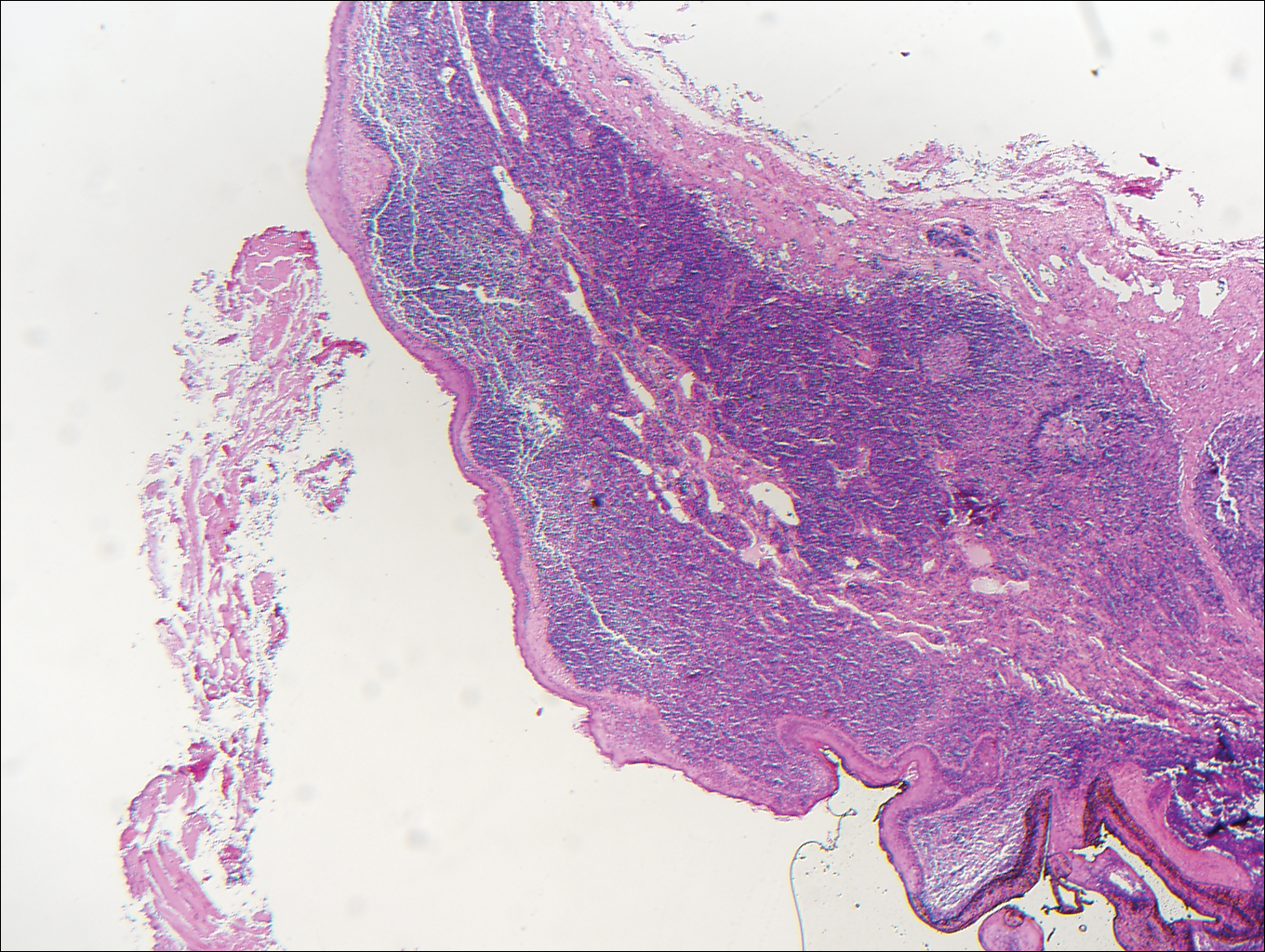

Balloon cell nevi often clinically present in young patients as bicolored nevi that sometimes are polypoid or verrucous in appearance with central yellow globules surrounded by a peripheral reticular pattern on dermoscopy. Histologically, balloon cell nevi are characterized by large cells with small, round, centrally located basophilic nuclei and clear foamy cytoplasm (Figure 1), which are thought to be formed by progressive vacuolization of melanocytes due to the enlargement and disintegration of melanosomes. This ballooning change reflects an seen in malignant melanoma, in which case nuclear pleomorphism, atypia, and increased mitotic activity also are observed. The prominent vascular network characteristic of RCC typically is not present.16

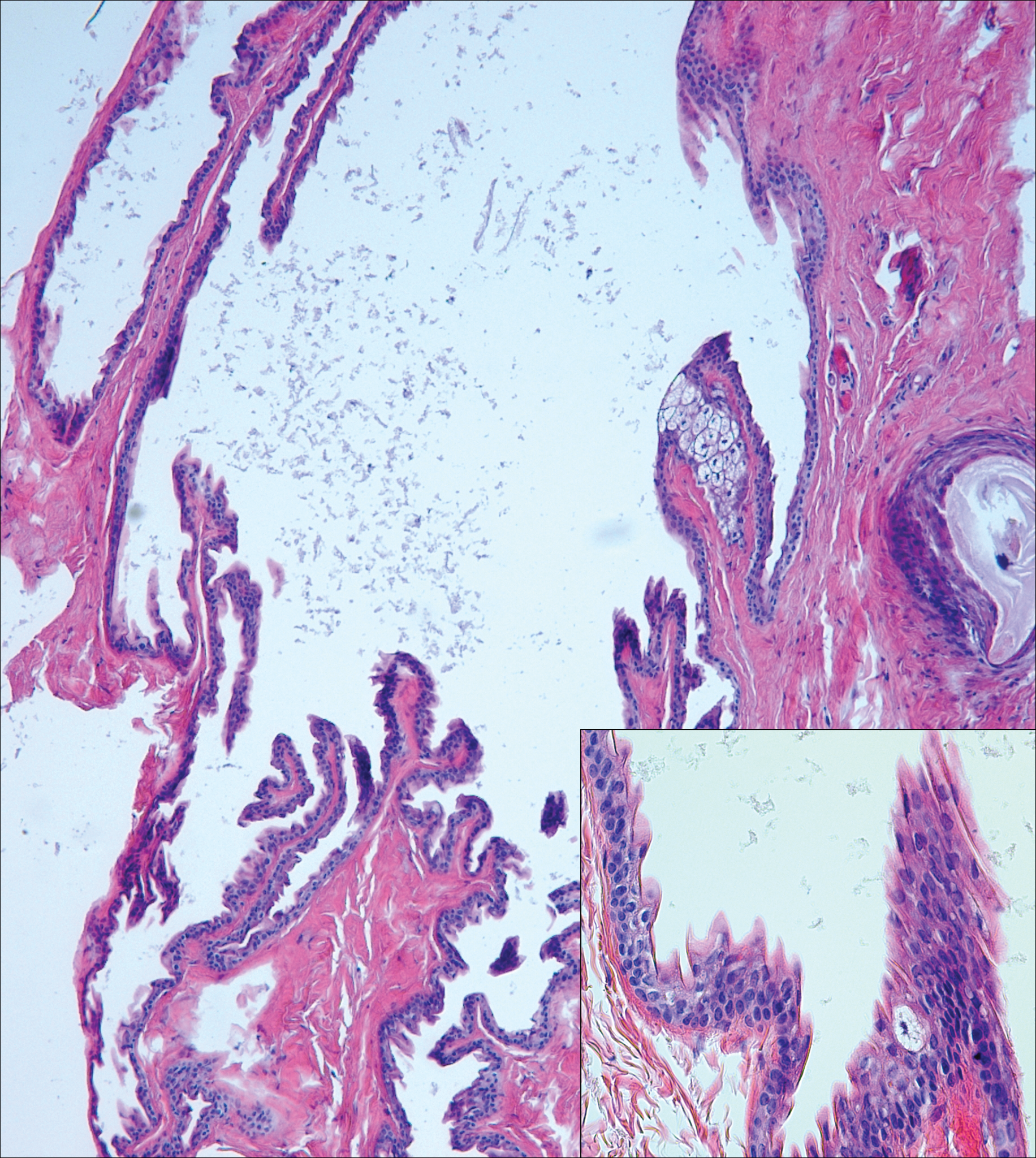

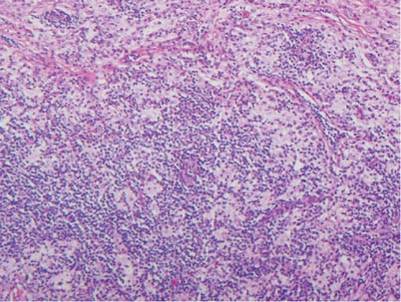

Clear cell hidradenomas are benign skin appendage tumors that often present as small, firm, solitary dermal nodules that may extend into the subcutaneous fat. They have a predilection for the head, face, and arms and demonstrate 2 predominant cell types, including a polyhedral cell with a rounded nucleus and slightly basophilic cytoplasm as well as a round cell with clear cytoplasm and bland nuclei (Figure 2). The latter cell type is less common, representing the predominant cell type in less than one-third of hidradenomas, and can present a diagnostic quandary based on histologic similarity to other clear cell neoplasms. The clear cells contain glycogen but no lipid. Ductlike structures often are present, and the intervening stroma varies from delicate vascularized cords of fibrous tissue to dense hyalinized collagen. Immunohistochemistry may be required for definitive diagnosis, and clear cell hidradenomas should react with monoclonal antibodies that label both eccrine and apocrine secretory elements, such as cytokeratins 6/18, 7, and 8/18.17

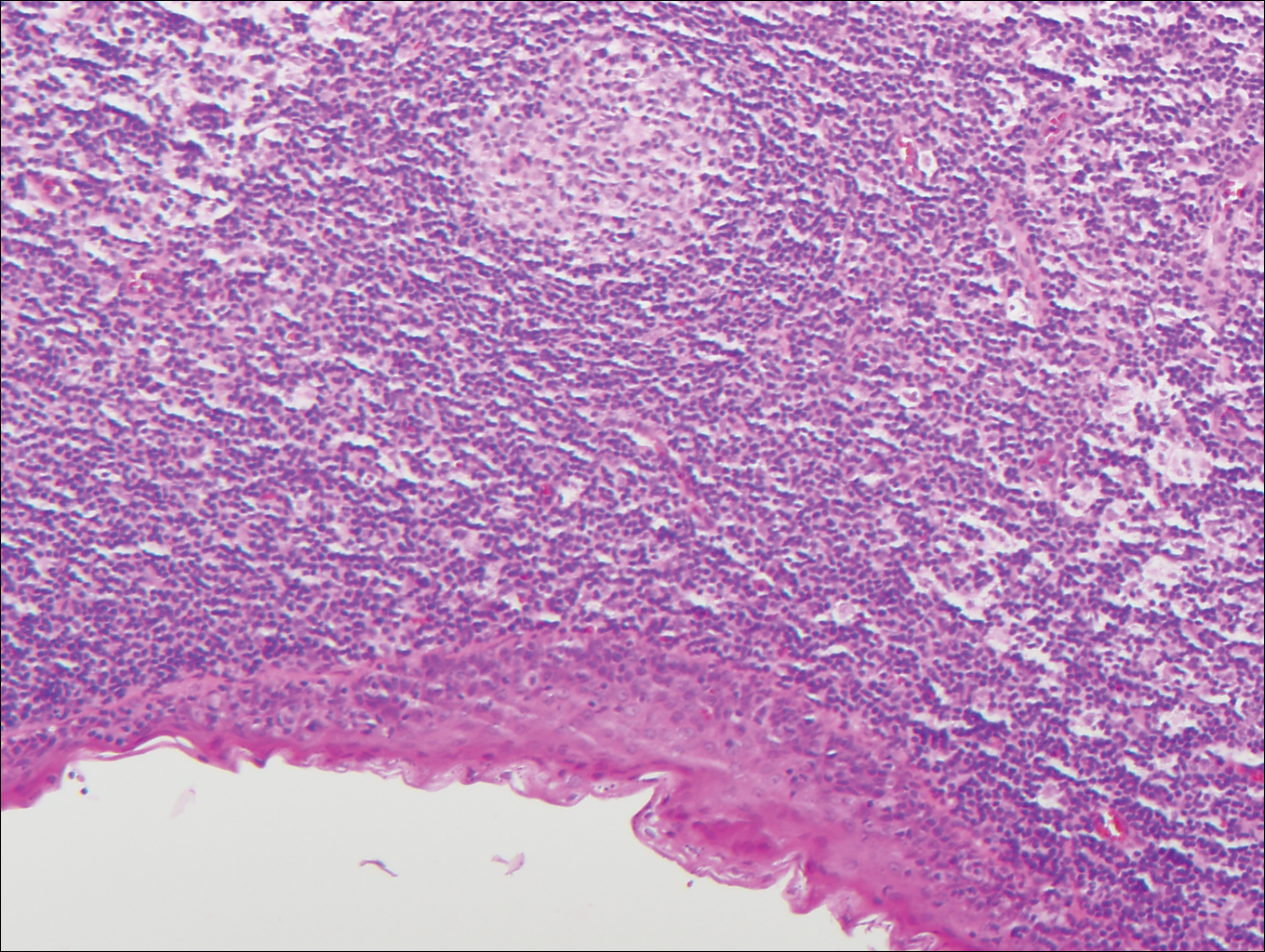

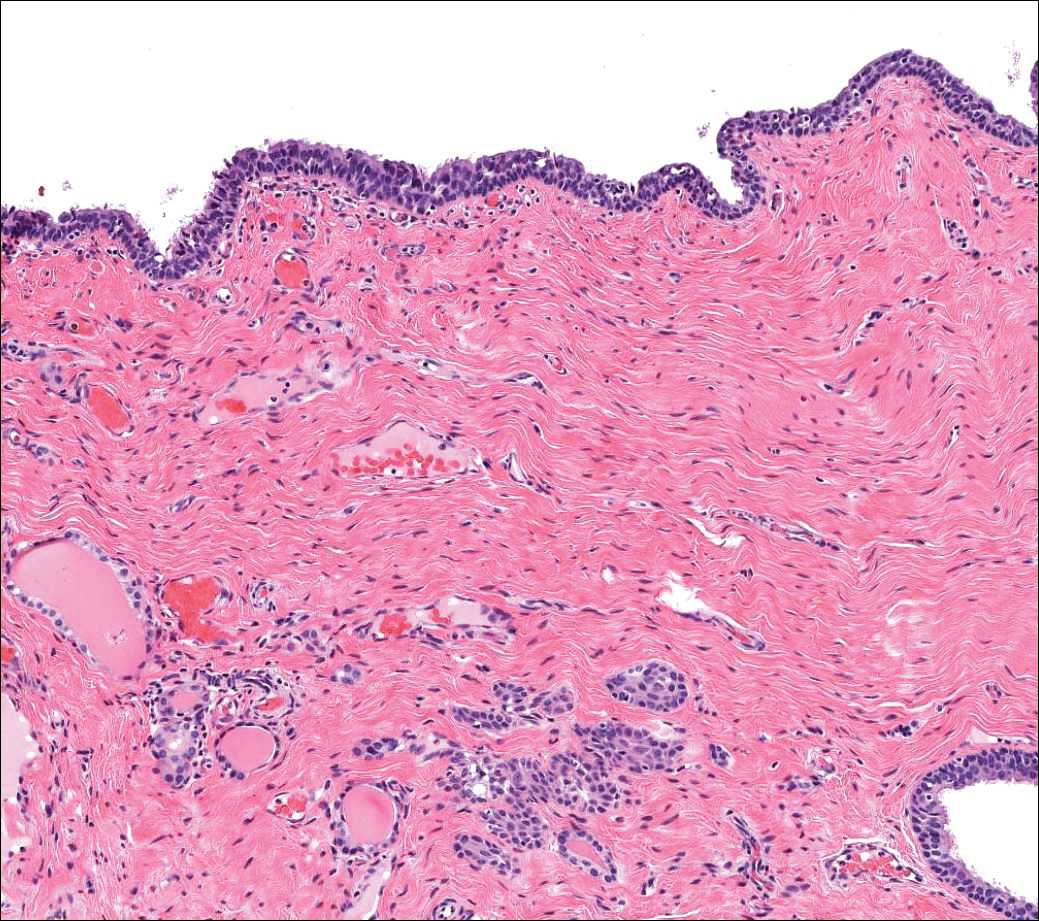

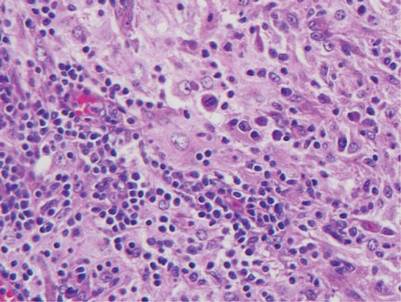

Pyogenic granulomas (also referred to as lobular capillary hemangiomas) are common and present clinically as rapidly growing, polypoid, red masses surrounded by a thickened epidermis that often are found on the fingers or lips. This entity is benign and often regresses spontaneously. Histologically, pyogenic granulomas are characterized by a lobular pattern of vascular proliferation associated with edema and inflammation resembling granulation tissue, with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis at the edges of the lesion (Figure 3).18

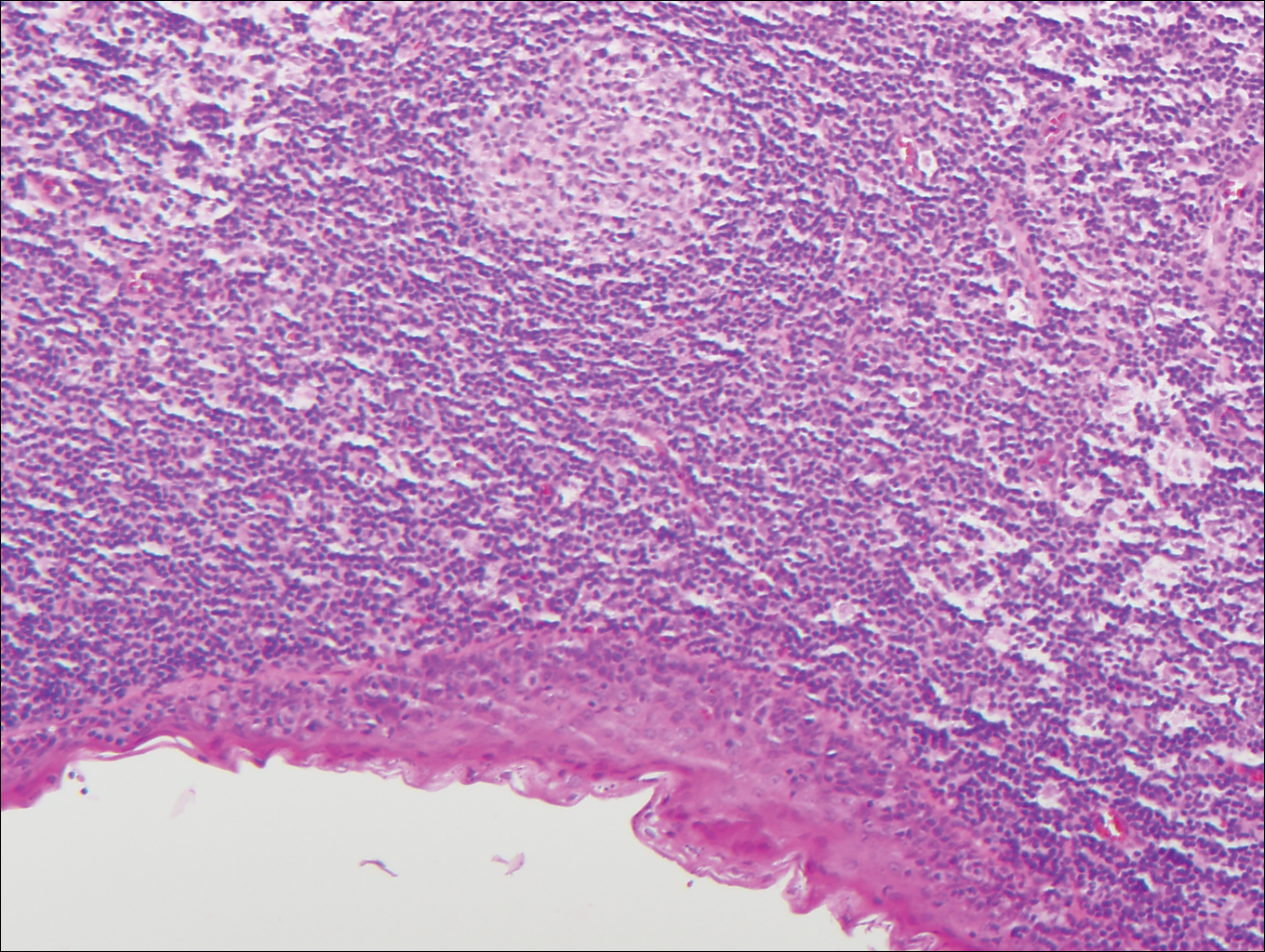

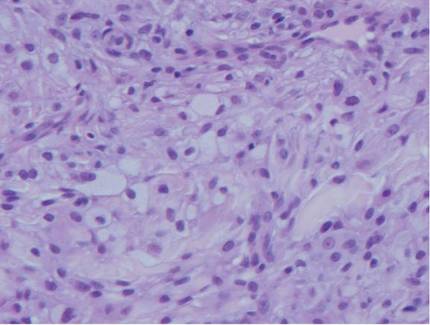

Sebaceous carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from the cells of the sebaceous glands and occurring most commonly in the periorbital area. This neoplasm most often affects older adults, with a mean age at diagnosis of 63 to 77 years. It commonly presents as a solitary nodule with yellowish discoloration and madarosis, which is a key distinguishing feature to differentiate this entity from a chalazion or hordeolum. Histologically, sebaceous carcinoma is a dermal-based infiltrative, nodular tumor with varying degrees of clear cell changes—well-differentiated tumors show more clear cell change as compared to more poorly differentiated variants—along with basaloid or squamous features and abundant mitotic activity (Figure 4), which may be useful in distinguishing it from the other entities in the clear cell neoplasm differential.19-22

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a common genitourinary system malignancy with incidence peaking between 50 and 70 years of age and a male predominance.1 The clear cell variant is the most common subtype of RCC, accounting for 70% to 75% of all cases. It is known to be a highly aggressive malignancy that frequently metastasizes to the lungs, lymphatics, bones, liver, and brain.2,3 Approximately 20% to 50% of patients with RCC eventually will develop metastasis after nephrectomy.4 Survival with metastatic RCC to any site typically is in the range of 10 to 22 months.5,6 Cutaneous metastases of RCC rarely have been reported in the literature (3%–6% of cases7) and most commonly are found on the scalp, followed by the chest or abdomen. 8 Cutaneous metastases generally are regarded as a late manifestation of the disease with a very poor prognosis. 9 It is unusual to identify cutaneous RCC metastasis without known RCC or other symptoms consistent with advanced RCC, such as hematuria or abdominal/flank pain. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for an estimated 6% to 7% of all cutaneous metastatic lesions.10 Cutaneous metastatic lesions of RCC often are solitary and grow rapidly, with the clinical appearance of an erythematous or violaceous, nodular, highly vascular, and often hemorrhagic growth.9,11,12

Following the histologic diagnosis of metastatic clear cell RCC, our patient was referred to medical oncology for further workup. Magnetic resonance imaging and a positron emission tomography scan demonstrated widespread disease with a 7-cm left renal mass, liver and lung metastases, and bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was started on combination immunotherapy as a palliative treatment given the widespread disease.

Histologically, clear cell RCC is characterized by lipid and glycogen-rich cells with ample cytoplasm and a well-developed vascular network, which often is thin walled with a chicken wire–like architecture. Metastatic clear cell RCC tumor cells may form glandular, acinar, or papillary structures with variable lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates and abundant capillary formation. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells should demonstrate positivity for paired box gene 8, PAX8, and RCC marker antigen.13 Vimentin and carcinoembryonic antigen may be utilized to distinguish from hidradenoma as carcinoembryonic antigen will be positive in hidradenoma and vimentin will be negative.14 Renal cell carcinoma also has a common molecular signature of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene inactivation as well as upregulation of hypoxia inducible factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.15

Balloon cell nevi often clinically present in young patients as bicolored nevi that sometimes are polypoid or verrucous in appearance with central yellow globules surrounded by a peripheral reticular pattern on dermoscopy. Histologically, balloon cell nevi are characterized by large cells with small, round, centrally located basophilic nuclei and clear foamy cytoplasm (Figure 1), which are thought to be formed by progressive vacuolization of melanocytes due to the enlargement and disintegration of melanosomes. This ballooning change reflects an seen in malignant melanoma, in which case nuclear pleomorphism, atypia, and increased mitotic activity also are observed. The prominent vascular network characteristic of RCC typically is not present.16

Clear cell hidradenomas are benign skin appendage tumors that often present as small, firm, solitary dermal nodules that may extend into the subcutaneous fat. They have a predilection for the head, face, and arms and demonstrate 2 predominant cell types, including a polyhedral cell with a rounded nucleus and slightly basophilic cytoplasm as well as a round cell with clear cytoplasm and bland nuclei (Figure 2). The latter cell type is less common, representing the predominant cell type in less than one-third of hidradenomas, and can present a diagnostic quandary based on histologic similarity to other clear cell neoplasms. The clear cells contain glycogen but no lipid. Ductlike structures often are present, and the intervening stroma varies from delicate vascularized cords of fibrous tissue to dense hyalinized collagen. Immunohistochemistry may be required for definitive diagnosis, and clear cell hidradenomas should react with monoclonal antibodies that label both eccrine and apocrine secretory elements, such as cytokeratins 6/18, 7, and 8/18.17

Pyogenic granulomas (also referred to as lobular capillary hemangiomas) are common and present clinically as rapidly growing, polypoid, red masses surrounded by a thickened epidermis that often are found on the fingers or lips. This entity is benign and often regresses spontaneously. Histologically, pyogenic granulomas are characterized by a lobular pattern of vascular proliferation associated with edema and inflammation resembling granulation tissue, with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis at the edges of the lesion (Figure 3).18

Sebaceous carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant neoplasm arising from the cells of the sebaceous glands and occurring most commonly in the periorbital area. This neoplasm most often affects older adults, with a mean age at diagnosis of 63 to 77 years. It commonly presents as a solitary nodule with yellowish discoloration and madarosis, which is a key distinguishing feature to differentiate this entity from a chalazion or hordeolum. Histologically, sebaceous carcinoma is a dermal-based infiltrative, nodular tumor with varying degrees of clear cell changes—well-differentiated tumors show more clear cell change as compared to more poorly differentiated variants—along with basaloid or squamous features and abundant mitotic activity (Figure 4), which may be useful in distinguishing it from the other entities in the clear cell neoplasm differential.19-22

- Alves de Paula T, Lopes da Silva P, Sueth Berriel LG. Renal cell carcinoma with cutaneous metastasis: case report. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32:213-215.

- Amaadour L, Atreche L, Azegrar M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J Cancer Ther. 2017;8:603-607.

- Weiss L, Harlos JP, Torhorst J, et al. Metastatic patterns of renal carcinoma: an analysis of 687 necropsies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:605-612.

- Flamigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:385-390.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwarz LH, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:453-463.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor–targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5694-5799.

- Smyth LG, Rowan GC, David MQ. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as an ominous metachronous scalp metastasis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:E64-E66.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Koga S, Tsuda S, Nishikido M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the skin. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:1939-1940.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a metaanalysis of the data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Amano Y, Ohni S, Ishige T, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis from a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with an eosinophilic cell component to the submandibular region. J Nihon Univ Med Assoc. 2015;74:73-77.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Sangoi AR, Karamchandani J, Kim J, et al. The use of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a review of PAX-8, PAX-2, hKIM-1, RCCma, and CD10. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:377-393.

- Velez MJ, Thomas CL, Stratton J, et al. The utility of using immunohistochemistry in the differentiation of metastatic, cutaneous clear cell renal cell carcinoma and clear cell hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:612-615.

- Nezami BG, MacLennan G. Clear cell. PathologyOutlines website. Published April 20, 2021. Updated March 2, 2022. Accessed April 22, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/kidneytumormalignantrccclear.html

- Dhaille F, Courville P, Joly P, et al. Balloon cell nevus: histologic and dermoscopic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:E55-E56.

- Volmar KE, Cummings TJ, Wang WH, et al. Clear cell hidradenoma: a mimic of metastatic clear cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:E113-E116.

- Hale CS. Capillary/pyogenic granuloma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 1, 2012. Updated March 10, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticpyogenicgranuloma.html

- Zada S, Lee BA. Sebaceous carcinoma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 11, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticsebaceouscarcinoma.html

- Kahana A, Pribila, JT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

- Wick MR. Cutaneous tumors and pseudotumors of the head and neck. In: Gnepp DR, ed. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2009:975-1068.

- Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma. In: Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al, eds. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:174-179.

- Alves de Paula T, Lopes da Silva P, Sueth Berriel LG. Renal cell carcinoma with cutaneous metastasis: case report. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32:213-215.

- Amaadour L, Atreche L, Azegrar M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. J Cancer Ther. 2017;8:603-607.

- Weiss L, Harlos JP, Torhorst J, et al. Metastatic patterns of renal carcinoma: an analysis of 687 necropsies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1988;114:605-612.

- Flamigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:385-390.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwarz LH, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:453-463.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor–targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5694-5799.

- Smyth LG, Rowan GC, David MQ. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as an ominous metachronous scalp metastasis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:E64-E66.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Koga S, Tsuda S, Nishikido M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the skin. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:1939-1940.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a metaanalysis of the data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Amano Y, Ohni S, Ishige T, et al. A case of cutaneous metastasis from a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with an eosinophilic cell component to the submandibular region. J Nihon Univ Med Assoc. 2015;74:73-77.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Sangoi AR, Karamchandani J, Kim J, et al. The use of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a review of PAX-8, PAX-2, hKIM-1, RCCma, and CD10. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:377-393.

- Velez MJ, Thomas CL, Stratton J, et al. The utility of using immunohistochemistry in the differentiation of metastatic, cutaneous clear cell renal cell carcinoma and clear cell hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:612-615.

- Nezami BG, MacLennan G. Clear cell. PathologyOutlines website. Published April 20, 2021. Updated March 2, 2022. Accessed April 22, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/kidneytumormalignantrccclear.html

- Dhaille F, Courville P, Joly P, et al. Balloon cell nevus: histologic and dermoscopic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:E55-E56.

- Volmar KE, Cummings TJ, Wang WH, et al. Clear cell hidradenoma: a mimic of metastatic clear cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:E113-E116.

- Hale CS. Capillary/pyogenic granuloma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 1, 2012. Updated March 10, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticpyogenicgranuloma.html

- Zada S, Lee BA. Sebaceous carcinoma. Pathology Outlines website. Published August 11, 2021. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/skintumornonmelanocyticsebaceouscarcinoma.html

- Kahana A, Pribila, JT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

- Wick MR. Cutaneous tumors and pseudotumors of the head and neck. In: Gnepp DR, ed. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2009:975-1068.

- Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma. In: Cassarino DS, Dadras SS, Lindberg MR, et al, eds. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:174-179.

A 71-year-old man with no notable medical history presented with a bleeding nodule on the right lower cutaneous lip of 9 weeks’ duration. The patient denied any systemic symptoms. A shave biopsy was performed.

Enlarging Mass on the Lateral Neck

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

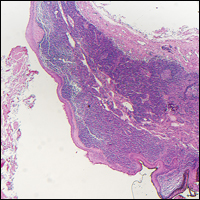

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

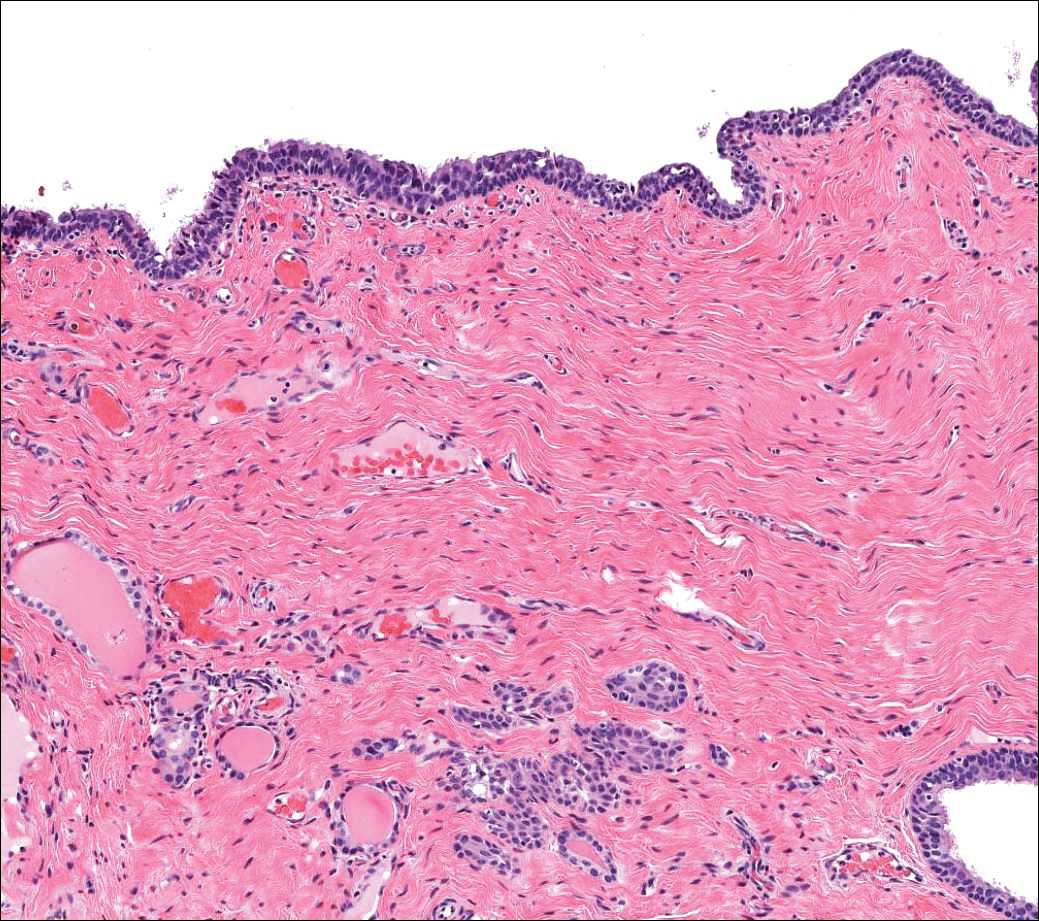

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

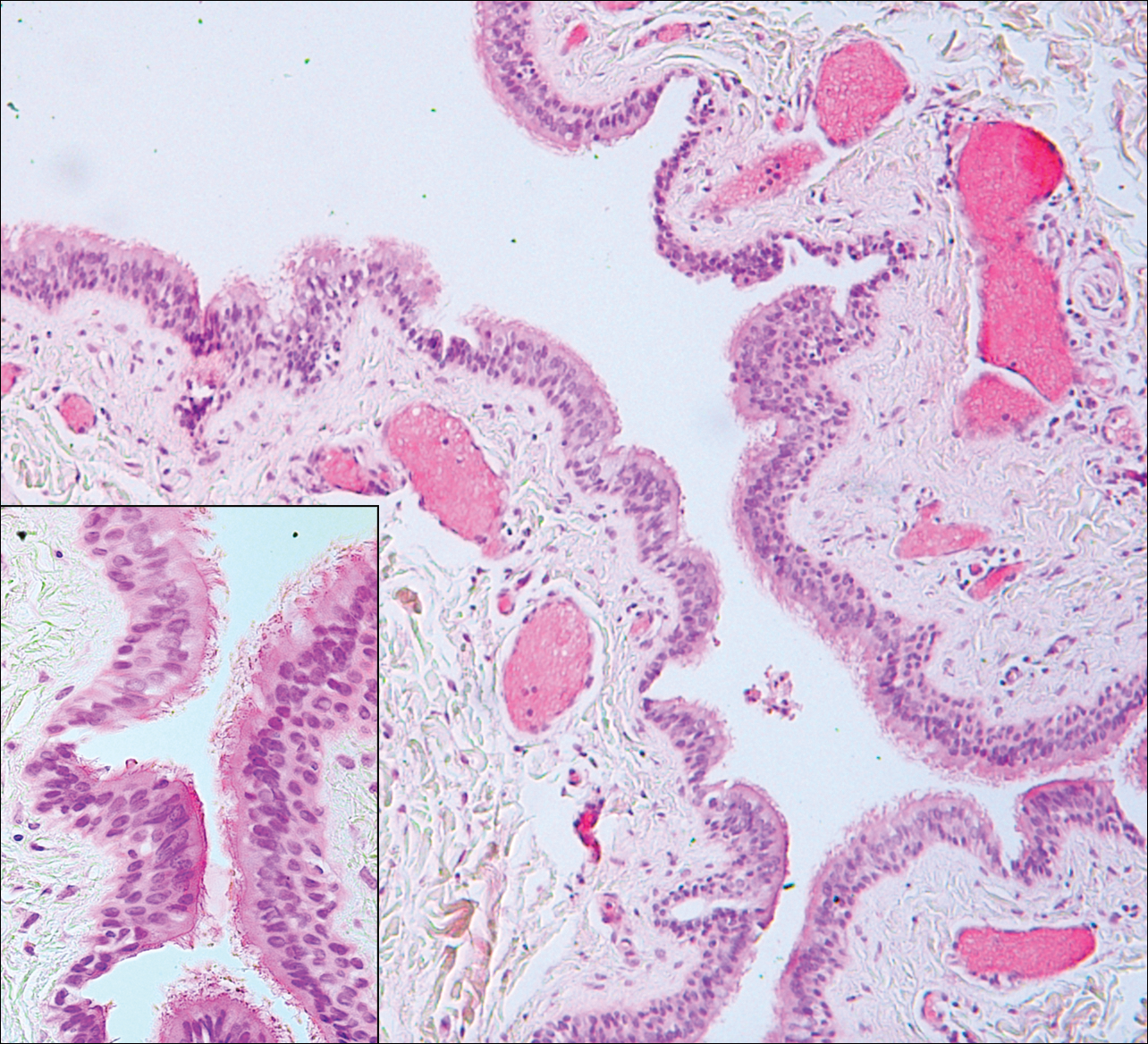

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

A 14-year-old adolescent boy presented with a nontender mass on the left lateral neck. The mass had been present since birth but had recently grown in size.

Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|  |

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|  | ||

|  |

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|  |

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|  | ||

|  |

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a rare benign histioproliferative disorder of unknown etiology.1 Clinically, it is most frequently characterized by massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy with other systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Accompanying laboratory findings include leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Extranodal involvement has been noted in more than 40% of cases, and cutaneous lesions represent the most common form of extranodal disease.2 Cutaneous RDD is a distinct and rare entity limited to the skin without lymphadenopathy or other extracutaneous involvement.3 Patients with cutaneous RDD typically present with papules and plaques that can grow to form nodules with satellite lesions that resolve into fibrotic plaques before spontaneous regression.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous lesions of RDD reveals a dense nodular dermal and often subcutaneous infiltrate of characteristic large polygonal histiocytes termed Rosai-Dorfman cells, which feature abundant pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct borders, and large vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,5 Some multinucleate forms may be seen. These Rosai-Dorfman cells display positive staining for CD68 and S-100, and negative staining for CD1a on immunohistochemistry. Lymphocytes and plasma cells often are admixed with the Rosai-Dorfman cells, and neutrophils and eosinophils also may be present in the infiltrate.4 The histologic hallmark of RDD is emperipolesis, a phenomenon whereby inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells reside intact within the cytoplasm of histiocytes (Figure 2).5

|  |

The histologic differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions of RDD includes other histiocytic and xanthomatous diseases, including eruptive xanthoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and solitary reticulohistiocytoma, which should not display emperipolesis. Eruptive xanthomas display collections of foamy histiocytes in the dermis and typically contain extracellular lipid. They may contain infiltrates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Juvenile xanthogranuloma also features a dense infiltrate of histiocytes in the papillary and reticular dermis but distinctly shows Touton giant cells and lipidization of histiocytes (Figure 4). Both eruptive xanthomas and juvenile xanthogranulomas typically stain negatively for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is histologically characterized by a dermal infiltrate of Langerhans cells that have their own distinctive morphologic features. They are uniformly ovoid with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei are smaller than those of Rosai-Dorfman cells and have a kidney bean shape with inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 5). Epidermotropism of these cells can be observed. Immunohistochemically, Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically is S-100 positive, CD1a positive, and langerin positive. Reticulohistiocytoma features histiocytes that have a characteristic dusty rose or ground glass cytoplasm with two-toned darker and lighter areas (Figure 6). Reticulohistiocytoma cells stain positively for CD68 but typically stain negatively for both CD1a and S-100.

|  | ||

|  |

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.

1. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

2. Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

3. Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385-391.

4. Wang KH, Chen WY, Lie HN, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathological profiles, spectrum and evolution of 21 lesions in six patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:277-286.

5. Chu P, LeBoit PE. Histologic features of cutaneous sinus histiocytosis (Rosai-Dorfman disease): study of cases both with and without systemic involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:201-206.