User login

When Should Hospitalists Order Continuous Cardiac Monitoring?

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

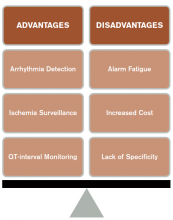

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

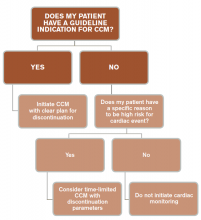

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.