User login

Bariatric Surgery + Medical Therapy: Effective Tx for T2DM?

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

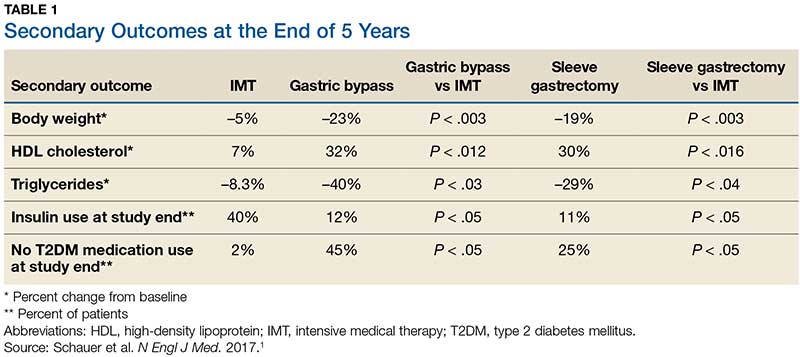

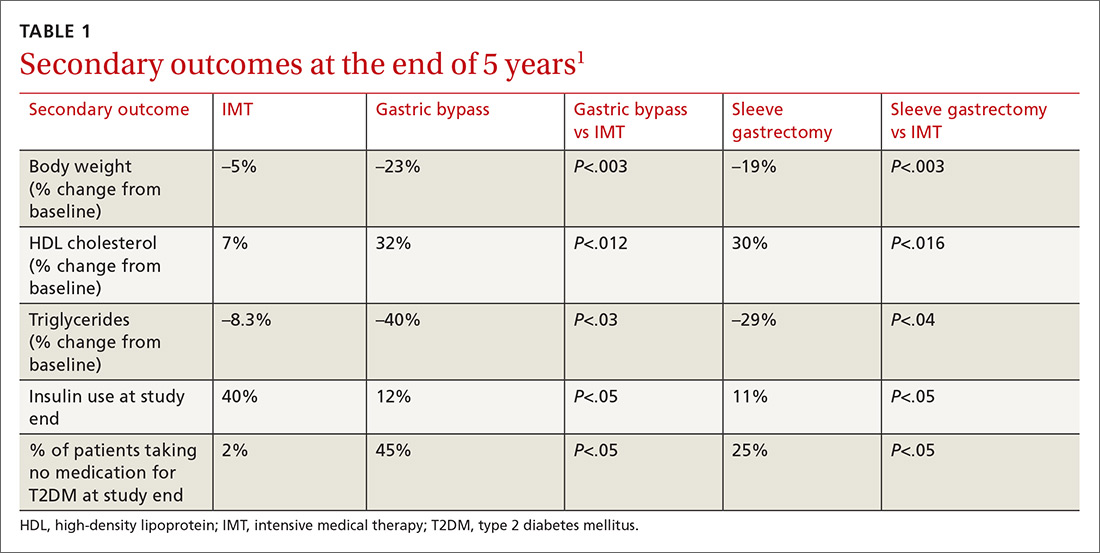

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

A 46-year-old woman presents with a BMI of 28, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and an A1C of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 U/d, with minimal change in A1C. Should you recommend bariatric surgery?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes, and at least 95% of those have T2DM.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Strategies may include making lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing insulin secretion, replacing insulin, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as firstline therapy for diabetes management, but these methods are often inadequate.2 In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for some populations with T2DM, the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for those with a BMI ≥ 35 and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4

However, this recommendation is based only on short-term studies. For example, in a single-center, nonblinded RCT of 60 patients with a BMI ≥ 35, the average baseline A1C levels of 8.65 ± 1.45% were reduced to 7.7 ± 0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4 ± 1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35), gastric bypass yielded better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy: 93% of patients in the former group and 47% of those in the latter group achieved remission of T2DM over a 12-month period.6

The current study by Schauer et al examined the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up: surgery + IMT works

This study was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were ages 20 to 60, had a BMI of 27 to 43, and had an A1C > 7%. Patients with a history of bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Patients were randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT (as defined by the ADA) only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an A1C ≤ 6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period, leaving 149. Of these, 134 completed the 5-year follow-up. Eight patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment, and 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an A1C of ≤ 6% than in the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients, 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 2 of 38 IMT patients). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the 2 surgery groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels and greater increases from baseline in HDL cholesterol levels; they also required less antidiabetes medication for glycemic control (see Table).1

WHAT’S NEW?

Big benefits, minimal adverse effects

Prior studies evaluating the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events, compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM in patients with a BMI ≥ 27, which is below the starting BMI (35) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications—eg, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis—in this patient population is significant.1 Other potential complications include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1C, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up, compared with patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to those of IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[2]:102-104).

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Association. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011; 146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

Bariatric surgery + medical therapy: Effective Tx for T2DM?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 46-year-old woman presents with a body mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and a glycated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 units/d, with minimal change in HgbA1c. Should you recommend bariatric surgery as an option for the treatment of diabetes?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes and at least 95% of those have type 2.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal in order to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Treatment strategies may include lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing secretion of insulin, insulin replacement, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as first-line therapy for the management of diabetes,2 but these by themselves are often inadequate. In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for other populations with T2DM (see the PURL, “How do these 3 diabetes agents compare in reducing mortality?”), the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for the treatment of patients with T2DM, a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4 However, this recommendation from the ADA supporting bariatric surgery is based only on short-term studies.

For example, one single-center nonblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 60 patients with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 found reductions in HgbA1C levels from the average baseline of 8.65±1.45% to 7.7±0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4±1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35 kg/m2), gastric bypass had better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy, with 93% of patients in the gastric bypass group achieving remission of T2DM vs 47% of patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P=.02) over a 12-month period.6

The current study sought to examine the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up shows surgery + intensive medical therapy works

This study by Schauer et al was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were 20 to 60 years of age, had a BMI of 27 to 43 kg/m2, and had an HgbA1C >7%. Patients with previous bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Each patient was randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. All patients underwent IMT as defined by the ADA. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an HgbA1c ≤6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period leaving 149; 134 completed the 5-year follow-up; 8 patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment; an additional 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an HgbA1c of ≤6% compared with the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.01; 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.03). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels, and greater increases from baseline in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels; they also required less diabetic medication for glycemic control (see TABLE 11). However, when data were imputed for the intention-to-treat analysis, P-values were P=0.08 for gastric bypass and P=0.17 for sleeve gastrectomy compared with the IMT group for lowering HgbA1c.

WHAT’S NEW?

Adding surgery has big benefits with minimal adverse effects

Prior studies that evaluated the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM for patients with a BMI ≥27 kg/m2, which is below the starting BMI (35 kg/m2) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis, in this patient population is significant.1 Complications can include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling regarding the possible complications is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1c, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size of the study...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who received gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up compared with the patients who received sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to that with IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and the cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Asssociation. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42 (suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 46-year-old woman presents with a body mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and a glycated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 units/d, with minimal change in HgbA1c. Should you recommend bariatric surgery as an option for the treatment of diabetes?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes and at least 95% of those have type 2.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal in order to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Treatment strategies may include lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing secretion of insulin, insulin replacement, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as first-line therapy for the management of diabetes,2 but these by themselves are often inadequate. In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for other populations with T2DM (see the PURL, “How do these 3 diabetes agents compare in reducing mortality?”), the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for the treatment of patients with T2DM, a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4 However, this recommendation from the ADA supporting bariatric surgery is based only on short-term studies.

For example, one single-center nonblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 60 patients with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 found reductions in HgbA1C levels from the average baseline of 8.65±1.45% to 7.7±0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4±1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35 kg/m2), gastric bypass had better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy, with 93% of patients in the gastric bypass group achieving remission of T2DM vs 47% of patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P=.02) over a 12-month period.6

The current study sought to examine the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up shows surgery + intensive medical therapy works

This study by Schauer et al was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were 20 to 60 years of age, had a BMI of 27 to 43 kg/m2, and had an HgbA1C >7%. Patients with previous bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Each patient was randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. All patients underwent IMT as defined by the ADA. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an HgbA1c ≤6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period leaving 149; 134 completed the 5-year follow-up; 8 patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment; an additional 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an HgbA1c of ≤6% compared with the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.01; 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.03). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels, and greater increases from baseline in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels; they also required less diabetic medication for glycemic control (see TABLE 11). However, when data were imputed for the intention-to-treat analysis, P-values were P=0.08 for gastric bypass and P=0.17 for sleeve gastrectomy compared with the IMT group for lowering HgbA1c.

WHAT’S NEW?

Adding surgery has big benefits with minimal adverse effects

Prior studies that evaluated the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM for patients with a BMI ≥27 kg/m2, which is below the starting BMI (35 kg/m2) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis, in this patient population is significant.1 Complications can include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling regarding the possible complications is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1c, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size of the study...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who received gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up compared with the patients who received sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to that with IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and the cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 46-year-old woman presents with a body mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and a glycated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 units/d, with minimal change in HgbA1c. Should you recommend bariatric surgery as an option for the treatment of diabetes?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes and at least 95% of those have type 2.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal in order to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Treatment strategies may include lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing secretion of insulin, insulin replacement, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as first-line therapy for the management of diabetes,2 but these by themselves are often inadequate. In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for other populations with T2DM (see the PURL, “How do these 3 diabetes agents compare in reducing mortality?”), the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for the treatment of patients with T2DM, a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4 However, this recommendation from the ADA supporting bariatric surgery is based only on short-term studies.

For example, one single-center nonblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 60 patients with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 found reductions in HgbA1C levels from the average baseline of 8.65±1.45% to 7.7±0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4±1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35 kg/m2), gastric bypass had better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy, with 93% of patients in the gastric bypass group achieving remission of T2DM vs 47% of patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P=.02) over a 12-month period.6

The current study sought to examine the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up shows surgery + intensive medical therapy works

This study by Schauer et al was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were 20 to 60 years of age, had a BMI of 27 to 43 kg/m2, and had an HgbA1C >7%. Patients with previous bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Each patient was randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. All patients underwent IMT as defined by the ADA. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an HgbA1c ≤6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period leaving 149; 134 completed the 5-year follow-up; 8 patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment; an additional 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an HgbA1c of ≤6% compared with the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.01; 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.03). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels, and greater increases from baseline in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels; they also required less diabetic medication for glycemic control (see TABLE 11). However, when data were imputed for the intention-to-treat analysis, P-values were P=0.08 for gastric bypass and P=0.17 for sleeve gastrectomy compared with the IMT group for lowering HgbA1c.

WHAT’S NEW?

Adding surgery has big benefits with minimal adverse effects

Prior studies that evaluated the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM for patients with a BMI ≥27 kg/m2, which is below the starting BMI (35 kg/m2) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis, in this patient population is significant.1 Complications can include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling regarding the possible complications is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1c, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size of the study...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who received gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up compared with the patients who received sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to that with IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and the cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Asssociation. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42 (suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Asssociation. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42 (suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

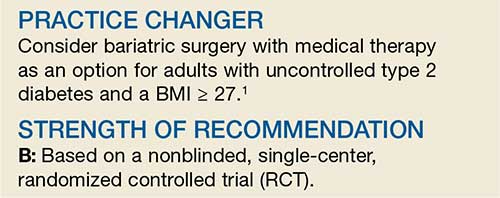

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider bariatric surgery with medical therapy as a treatment option for adults with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and a body mass index ≥27 kg/m2.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a nonblinded, single-center, randomized controlled trial.

Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

New Adjunctive Treatment Option for Venous Stasis Ulcers

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider adding simvastatin (40 mg/d) to standard wound care and compression for patients with venous stasis ulcers.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT).1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 74-year-old woman with chronic lower extremity edema seeks treatment for a nonhealing venous stasis ulcer. For the past nine months, she’s been wearing compression stockings and receiving intermittent home-based wound care, but nothing seems to help. She asks if there’s anything else she can try.

Venous stasis ulcers affect 1% of US adults and lead to substantial morbidity and more than $2 billion in annual health care expenditures.1,2 Edema management—generally limb elevation and compression therapy—has been the mainstay of therapy. Treatment can be lengthy, and ulcer recurrence is common.2,3

Statins have been found to aid wound healing through their diverse physiologic (pleiotropic) effects. Evidence indicates they can be beneficial in treatment of diabetic foot ulcers,4 pressure ulcers,5 and ulcerations associated with systemic sclerosis and Raynaud phenomenon.6 Evangelista et al1 investigated whether adding a statin to standard wound care and compression could improve venous stasis ulcer healing.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Ulcers more likely to close when statin added

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was performed at a large medical center in the Philippines. It was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of simvastatin (40 mg/d) for venous ulcer healing when combined with standard treatment (compression therapy, limb elevation, and standard wound care).1

Study subjects were 66 patients, ages 41 to 71, who’d had one or more venous ulcers for at least three months. They were randomly assigned to receive either simvastatin (40 mg/d; n = 32) or an identical-appearing placebo (n = 34). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, had an ulcer that was infected or > 10 cm in diameter, or were taking any medication that could interact with a statin. Patients were stratified according to ulcer diameter (≤ 5 cm and > 5 cm). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the duration of venous ulceration (3.80 y in the placebo group vs 3.93 y in the simvastatin group) or incidence of diabetes (5% vs 3%, respectively).

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients whose ulcers completely healed at 10 weeks. Secondary outcomes were measures of the total surface area healed, healing time, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores. Baseline ulcer diameter and surface area and DLQI scores were obtained prior to therapy initiation. The same dermatologist, who was blinded to the patients’ group assignments, evaluated all patients every two weeks until wound closure or for a maximum of 10 weeks.

Overall, 90% of the patients who received simvastatin had complete ulcer closure at 10 weeks, compared with 34% of patients in the control group (relative risk [RR], 0.16; number needed to treat [NNT], 2).

Among patients with ulcers ≤ 5 cm, 100% of the ulcers healed in the simvastatin group, compared to 50% in the control group (RR, 0.10; NNT, 2). Perhaps more importantly, in patients with ulcers > 5 cm, 67% in the simvastatin group had closure with a mean healing time of nine weeks, whereas none of the ulcers of this size closed in the control group (RR, 0.33; NNT, 1.5), and the mean healed area was significantly larger in patients who received simvastatin (28.9 cm2 vs 19.6 cm2).

In addition, in the simvastatin group, healing times were significantly reduced (7.53 ± 1.34 wk vs 8.55 ± 1.13 wk) and quality of life (as evaluated by DLQI scoring) significantly improved compared to the control group.

Study dropouts were minimal (8%; two in the placebo group and three in the intervention group). Using intention-to-treat analysis and worst-case scenarios for those who dropped out did not affect the primary outcome. There were no withdrawals due to adverse reactions.

WHAT’S NEW

Statins offer significant benefits for treating venous stasis ulcers

This is the first human study to investigate the use of a statin in venous stasis ulcer healing. This intervention demonstrated significant improvements in healing rate and time, a very small NNT for benefit, and improved patient quality of life compared to placebo.

Next page: Caveats >>

CAVEATS

Carefully selected patients

Many wounds will heal with compression therapy alone, as occurred in this study, in which 50% of ulcers ≤ 5 cm treated with standard therapy healed, albeit at a somewhat slower rate. Adding another medication to the regimen when target patients generally have multiple comorbidities should always prompt caution.

The study by Evangelista et al1 was performed in a select population, and the exclusion criteria included the use of some commonly prescribed medications, such as ACE inhibitors. No data were collected on patient BMI, which is a risk factor for delayed healing.

The prevalence of obesity is lower in the Philippines than in the US. It is uncertain what role this difference would have in the statin’s effectiveness.

Further studies, especially those conducted with a less selective population, would better clarify the generalizability of this intervention.

Nontheless, we found the results of this study impressive. The methods reported are rigorous and consistent with standard RCT methodologies.

This is the only study of a statin in human venous stasis disease, but studies in animals—and studies of statins for other types of ulcers in humans—have consistently suggested benefit. It seems hard to argue against adding this low-cost, low-risk intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

There are no known barriers to implementation of this practice.

REFERENCES

1. Evangelista MT, Casintahan MF, Villafuerte LL. Simvastatin as a novel therapeutic agent for venous ulcers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014; 170:1151-1157.

2. Collins L, Seraj S. Diagnosis and treatment of venous ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81: 989-996.

3. The Australian Wound Management Association Inc, New Zealand Wound Care Society Inc. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guideline for prevention and management of venous leg ulcers (2011). www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/ext003_venous_leg_ulcers_aust_nz_0.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

4. Johansen OE, Birkeland KI, Jørgensen AP, et al. Diabetic foot ulcer burden may be modified by high-dose atorvastatin: a 6-month randomized controlled pilot trial. J Diabetes. 2009; 1:182-187.

5. Farsaei S, Khalili H, Farboud ES, et al. Efficacy of topical atorvastatin for the treatment of pressure ulcers: a randomized clinical trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:19-27.

6. Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, Helmii M. Statins: potentially useful in therapy of systemic sclerosis-related Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1801-1808.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(3):182-184.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider adding simvastatin (40 mg/d) to standard wound care and compression for patients with venous stasis ulcers.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT).1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 74-year-old woman with chronic lower extremity edema seeks treatment for a nonhealing venous stasis ulcer. For the past nine months, she’s been wearing compression stockings and receiving intermittent home-based wound care, but nothing seems to help. She asks if there’s anything else she can try.

Venous stasis ulcers affect 1% of US adults and lead to substantial morbidity and more than $2 billion in annual health care expenditures.1,2 Edema management—generally limb elevation and compression therapy—has been the mainstay of therapy. Treatment can be lengthy, and ulcer recurrence is common.2,3

Statins have been found to aid wound healing through their diverse physiologic (pleiotropic) effects. Evidence indicates they can be beneficial in treatment of diabetic foot ulcers,4 pressure ulcers,5 and ulcerations associated with systemic sclerosis and Raynaud phenomenon.6 Evangelista et al1 investigated whether adding a statin to standard wound care and compression could improve venous stasis ulcer healing.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Ulcers more likely to close when statin added

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was performed at a large medical center in the Philippines. It was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of simvastatin (40 mg/d) for venous ulcer healing when combined with standard treatment (compression therapy, limb elevation, and standard wound care).1

Study subjects were 66 patients, ages 41 to 71, who’d had one or more venous ulcers for at least three months. They were randomly assigned to receive either simvastatin (40 mg/d; n = 32) or an identical-appearing placebo (n = 34). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, had an ulcer that was infected or > 10 cm in diameter, or were taking any medication that could interact with a statin. Patients were stratified according to ulcer diameter (≤ 5 cm and > 5 cm). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the duration of venous ulceration (3.80 y in the placebo group vs 3.93 y in the simvastatin group) or incidence of diabetes (5% vs 3%, respectively).

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients whose ulcers completely healed at 10 weeks. Secondary outcomes were measures of the total surface area healed, healing time, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores. Baseline ulcer diameter and surface area and DLQI scores were obtained prior to therapy initiation. The same dermatologist, who was blinded to the patients’ group assignments, evaluated all patients every two weeks until wound closure or for a maximum of 10 weeks.

Overall, 90% of the patients who received simvastatin had complete ulcer closure at 10 weeks, compared with 34% of patients in the control group (relative risk [RR], 0.16; number needed to treat [NNT], 2).

Among patients with ulcers ≤ 5 cm, 100% of the ulcers healed in the simvastatin group, compared to 50% in the control group (RR, 0.10; NNT, 2). Perhaps more importantly, in patients with ulcers > 5 cm, 67% in the simvastatin group had closure with a mean healing time of nine weeks, whereas none of the ulcers of this size closed in the control group (RR, 0.33; NNT, 1.5), and the mean healed area was significantly larger in patients who received simvastatin (28.9 cm2 vs 19.6 cm2).

In addition, in the simvastatin group, healing times were significantly reduced (7.53 ± 1.34 wk vs 8.55 ± 1.13 wk) and quality of life (as evaluated by DLQI scoring) significantly improved compared to the control group.

Study dropouts were minimal (8%; two in the placebo group and three in the intervention group). Using intention-to-treat analysis and worst-case scenarios for those who dropped out did not affect the primary outcome. There were no withdrawals due to adverse reactions.

WHAT’S NEW

Statins offer significant benefits for treating venous stasis ulcers

This is the first human study to investigate the use of a statin in venous stasis ulcer healing. This intervention demonstrated significant improvements in healing rate and time, a very small NNT for benefit, and improved patient quality of life compared to placebo.

Next page: Caveats >>

CAVEATS

Carefully selected patients

Many wounds will heal with compression therapy alone, as occurred in this study, in which 50% of ulcers ≤ 5 cm treated with standard therapy healed, albeit at a somewhat slower rate. Adding another medication to the regimen when target patients generally have multiple comorbidities should always prompt caution.

The study by Evangelista et al1 was performed in a select population, and the exclusion criteria included the use of some commonly prescribed medications, such as ACE inhibitors. No data were collected on patient BMI, which is a risk factor for delayed healing.

The prevalence of obesity is lower in the Philippines than in the US. It is uncertain what role this difference would have in the statin’s effectiveness.

Further studies, especially those conducted with a less selective population, would better clarify the generalizability of this intervention.

Nontheless, we found the results of this study impressive. The methods reported are rigorous and consistent with standard RCT methodologies.

This is the only study of a statin in human venous stasis disease, but studies in animals—and studies of statins for other types of ulcers in humans—have consistently suggested benefit. It seems hard to argue against adding this low-cost, low-risk intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

There are no known barriers to implementation of this practice.

REFERENCES

1. Evangelista MT, Casintahan MF, Villafuerte LL. Simvastatin as a novel therapeutic agent for venous ulcers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014; 170:1151-1157.

2. Collins L, Seraj S. Diagnosis and treatment of venous ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81: 989-996.

3. The Australian Wound Management Association Inc, New Zealand Wound Care Society Inc. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guideline for prevention and management of venous leg ulcers (2011). www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/ext003_venous_leg_ulcers_aust_nz_0.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

4. Johansen OE, Birkeland KI, Jørgensen AP, et al. Diabetic foot ulcer burden may be modified by high-dose atorvastatin: a 6-month randomized controlled pilot trial. J Diabetes. 2009; 1:182-187.

5. Farsaei S, Khalili H, Farboud ES, et al. Efficacy of topical atorvastatin for the treatment of pressure ulcers: a randomized clinical trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:19-27.

6. Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, Helmii M. Statins: potentially useful in therapy of systemic sclerosis-related Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1801-1808.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(3):182-184.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider adding simvastatin (40 mg/d) to standard wound care and compression for patients with venous stasis ulcers.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT).1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 74-year-old woman with chronic lower extremity edema seeks treatment for a nonhealing venous stasis ulcer. For the past nine months, she’s been wearing compression stockings and receiving intermittent home-based wound care, but nothing seems to help. She asks if there’s anything else she can try.

Venous stasis ulcers affect 1% of US adults and lead to substantial morbidity and more than $2 billion in annual health care expenditures.1,2 Edema management—generally limb elevation and compression therapy—has been the mainstay of therapy. Treatment can be lengthy, and ulcer recurrence is common.2,3

Statins have been found to aid wound healing through their diverse physiologic (pleiotropic) effects. Evidence indicates they can be beneficial in treatment of diabetic foot ulcers,4 pressure ulcers,5 and ulcerations associated with systemic sclerosis and Raynaud phenomenon.6 Evangelista et al1 investigated whether adding a statin to standard wound care and compression could improve venous stasis ulcer healing.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Ulcers more likely to close when statin added

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was performed at a large medical center in the Philippines. It was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of simvastatin (40 mg/d) for venous ulcer healing when combined with standard treatment (compression therapy, limb elevation, and standard wound care).1

Study subjects were 66 patients, ages 41 to 71, who’d had one or more venous ulcers for at least three months. They were randomly assigned to receive either simvastatin (40 mg/d; n = 32) or an identical-appearing placebo (n = 34). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, had an ulcer that was infected or > 10 cm in diameter, or were taking any medication that could interact with a statin. Patients were stratified according to ulcer diameter (≤ 5 cm and > 5 cm). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the duration of venous ulceration (3.80 y in the placebo group vs 3.93 y in the simvastatin group) or incidence of diabetes (5% vs 3%, respectively).

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients whose ulcers completely healed at 10 weeks. Secondary outcomes were measures of the total surface area healed, healing time, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores. Baseline ulcer diameter and surface area and DLQI scores were obtained prior to therapy initiation. The same dermatologist, who was blinded to the patients’ group assignments, evaluated all patients every two weeks until wound closure or for a maximum of 10 weeks.

Overall, 90% of the patients who received simvastatin had complete ulcer closure at 10 weeks, compared with 34% of patients in the control group (relative risk [RR], 0.16; number needed to treat [NNT], 2).

Among patients with ulcers ≤ 5 cm, 100% of the ulcers healed in the simvastatin group, compared to 50% in the control group (RR, 0.10; NNT, 2). Perhaps more importantly, in patients with ulcers > 5 cm, 67% in the simvastatin group had closure with a mean healing time of nine weeks, whereas none of the ulcers of this size closed in the control group (RR, 0.33; NNT, 1.5), and the mean healed area was significantly larger in patients who received simvastatin (28.9 cm2 vs 19.6 cm2).

In addition, in the simvastatin group, healing times were significantly reduced (7.53 ± 1.34 wk vs 8.55 ± 1.13 wk) and quality of life (as evaluated by DLQI scoring) significantly improved compared to the control group.

Study dropouts were minimal (8%; two in the placebo group and three in the intervention group). Using intention-to-treat analysis and worst-case scenarios for those who dropped out did not affect the primary outcome. There were no withdrawals due to adverse reactions.

WHAT’S NEW

Statins offer significant benefits for treating venous stasis ulcers

This is the first human study to investigate the use of a statin in venous stasis ulcer healing. This intervention demonstrated significant improvements in healing rate and time, a very small NNT for benefit, and improved patient quality of life compared to placebo.

Next page: Caveats >>

CAVEATS

Carefully selected patients

Many wounds will heal with compression therapy alone, as occurred in this study, in which 50% of ulcers ≤ 5 cm treated with standard therapy healed, albeit at a somewhat slower rate. Adding another medication to the regimen when target patients generally have multiple comorbidities should always prompt caution.

The study by Evangelista et al1 was performed in a select population, and the exclusion criteria included the use of some commonly prescribed medications, such as ACE inhibitors. No data were collected on patient BMI, which is a risk factor for delayed healing.

The prevalence of obesity is lower in the Philippines than in the US. It is uncertain what role this difference would have in the statin’s effectiveness.

Further studies, especially those conducted with a less selective population, would better clarify the generalizability of this intervention.

Nontheless, we found the results of this study impressive. The methods reported are rigorous and consistent with standard RCT methodologies.

This is the only study of a statin in human venous stasis disease, but studies in animals—and studies of statins for other types of ulcers in humans—have consistently suggested benefit. It seems hard to argue against adding this low-cost, low-risk intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

There are no known barriers to implementation of this practice.

REFERENCES

1. Evangelista MT, Casintahan MF, Villafuerte LL. Simvastatin as a novel therapeutic agent for venous ulcers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014; 170:1151-1157.

2. Collins L, Seraj S. Diagnosis and treatment of venous ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81: 989-996.

3. The Australian Wound Management Association Inc, New Zealand Wound Care Society Inc. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guideline for prevention and management of venous leg ulcers (2011). www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/ext003_venous_leg_ulcers_aust_nz_0.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2015.

4. Johansen OE, Birkeland KI, Jørgensen AP, et al. Diabetic foot ulcer burden may be modified by high-dose atorvastatin: a 6-month randomized controlled pilot trial. J Diabetes. 2009; 1:182-187.

5. Farsaei S, Khalili H, Farboud ES, et al. Efficacy of topical atorvastatin for the treatment of pressure ulcers: a randomized clinical trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:19-27.

6. Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, Helmii M. Statins: potentially useful in therapy of systemic sclerosis-related Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1801-1808.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(3):182-184.

A new adjunctive Tx option for venous stasis ulcers

Consider adding simvastatin 40 mg/d to standard wound care and compression for patients with venous stasis ulcers.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Evangelista MT, Casintahan MF, Villafuerte LL. Simvastatin as a novel therapeutic agent for venous ulcers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1151-1157.

Illustrative case

A 74-year-old woman with chronic lower extremity edema seeks treatment for a nonhealing venous stasis ulcer. For the past 9 months, she’s been wearing compression stockings and receiving intermittent home-based wound care, but nothing seems to help. She asks if there’s anything else she can try.

Venous stasis ulcers affect 1% of US adults and lead to substantial morbidity and more than $2 billion in annual health care expenditures.1,2 Edema management—generally limb elevation and compression therapy—has been the mainstay of therapy. Treatment can be lengthy, and ulcer recurrences are common.2,3

Statins have been found to help wound healing through their diverse physiologic (pleiotropic) effects. Evidence shows they can be beneficial for treating diabetic foot ulcers,4 pressure ulcers,5 and ulcerations associated with systemic sclerosis and Raynaud’s phenomenon.6 Evangelista et al1 investigated whether adding a statin to standard wound care and compression could improve venous stasis ulcer healing.

STUDY SUMMARY: Ulcers are more likely to close when a statin is added to standard care

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was performed at a large medical center in the Philippines. It was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of simvastatin 40 mg/d for venous ulcer healing when combined with standard treatment (compression therapy, limb elevation, and standard wound care).1

Researchers randomized 66 patients ages 41 to 71 who’d had one or more venous ulcers for at least 3 months to receive either simvastatin 40 mg/d (N=32) or an identical appearing placebo (N=34). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, had an ulcer that was infected or >10 cm in diameter, or were taking any medication that could interact with a statin. Patients were stratified according to ulcer diameter (≤5 cm and >5 cm). There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in the duration of venous ulceration (3.80 years in the placebo group vs 3.93 years in the simvastatin group) or incidence of diabetes (5% in the placebo group vs 3% in the simvastatin group).

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients whose ulcers completely healed at 10 weeks. Secondary outcomes were measures of the total surface area healed and healing time, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores. Baseline ulcer diameter and surface area and DLQI scores were obtained prior to therapy. The same dermatologist, who was blinded to the patients’ assigned group, evaluated all patients every 2 weeks until wound closure or for a maximum of 10 weeks.

Overall, 90% of the patients who received simvastatin had complete ulcer closure at 10 weeks, compared with 34% of patients in the control group (relative risk [RR]=0.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.05-0.47; number needed to treat [NNT]=2).

Among patients with ulcers ≤5 cm, 100% of the ulcers healed in the simvastatin group, compared to 50% in the control group (RR=0.10; 95% CI, 0.01-0.71; NNT=2). Perhaps more importantly, in patients with ulcers >5 cm, 67% of the ulcers in the simvastatin group had closure with a mean healing time of 9 weeks, whereas none of the ulcers of this size closed in the control group (RR=0.33; 95% CI, 0.12-0.84; NNT=1.5), and the mean healed area was significantly larger in patients who received simvastatin (28.9 cm2 vs 19.6 cm2; P=.03).

In addition, in the simvastatin group, healing times were significantly reduced (7.53±1.34 weeks vs 8.55±1.13 weeks) and quality of life (as evaluated by DLQI scoring) significantly improved compared to the control group.

Study dropouts (8%; 2 in the placebo group and 3 in the intervention group) were minimal. Using intention-to-treat analysis and worst-case scenarios for dropouts did not affect the primary outcome. There were no withdrawals for adverse reactions.

WHAT’S NEW: Statins offer significant benefits for treating venous stasis ulcers

This is the first human study to investigate the use of a statin in venous stasis ulcer healing. This intervention demonstrated significant improvements in healing rate and time, a very small NNT for benefit, and improved patient quality of life compared to placebo.

CAVEATS: Results were found in a carefully selected group of patients

Many wounds will heal with compression therapy alone, as occurred in this study, where 50% of ulcers ≤5 cm treated with standard therapy healed, albeit at a somewhat slower rate. Adding another medication to the regimen when these patients generally have multiple comorbidities should always prompt caution.

The study by Evangelista et al1 was performed in a select population, and the exclusion criteria included the use of some commonly prescribed medications, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. No data were collected on patient body mass index, which is a risk factor for delayed healing. The prevalence of obesity is lower in the Philippines than in the United States, and it is uncertain what role this difference would have in the statin’s effectiveness. Further studies, especially those conducted with a less selective population, would better clarify the generalizability of this intervention.

We found the results of this study impressive. The methods reported are rigorous and consistent with standard RCT methodologies. This is the only study of a statin in human venous stasis disease, but studies in animals—and studies of statins for other types of ulcers in humans—have consistently suggested benefit. It seems hard to argue against adding this low-cost, low-risk intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

There are no known barriers to implementing this practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.