User login

Supervising residents in an outpatient setting: 6 tips for success

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires supervision of residents “provides safe and effective care to patients; ensures each resident’s development of the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to enter the unsupervised practice of medicine; and establishes a foundation for continued professional growth.”1 Beyond delineating supervision types (direct, indirect, or oversight), best practices for outpatient supervision are lacking, which perhaps contributes to challenges and discrepancies in experiences involving both trainees and supervisors.2 In this article, I provide 6 practical recommendations for supervisors to address and overcome these challenges.

1. Don’t skip orientation

Resist the pressure to jump directly into clinical care. Devote the first supervision session to learner orientation about expectations (eg, documentation and between-visit patient outreach), logistics (eg, electronic health record or absences), clinic workflow and processes (eg, no-shows or referrals), and team members. Provide this verbally and in writing; the former fosters additional discussion and prompts questions, while the latter serves as a useful reference.

2. Plan for the end at the beginning

Plan ahead for end-of-rotation issues (eg, transfers of care or clinician sign-out), particularly because handoffs are known patient safety risks.3 Provide a written sign-out template or example, set a deadline for the first draft, and ensure known verbal sign-out occurs to both you and any trainees coming into the rotation.

3. Facilitate self-identification of strengths, weaknesses, and goals

Individual learning plans (ILPs) are a fundamental component of adult learning theory, allowing for self-directed learning and ongoing assessment by trainee and supervisor. Complete the ILP together at the beginning of the rotation and regularly devote time to revisit and revise it. This process ensures targeted feedback, which will reduce the stress and potential surprises often associated with end-of-rotation evaluations.

4. Consider the homework you assign

Be intentional about assigned readings. Consider their frequency and length, highlight where you want learners to focus, provide self-reflection questions/prompts, and take time to discuss during supervision. If you use a structured curriculum, maintain flexibility so your trainees’ interests, topics arising in real-time clinical care, and relevant in-press articles can be included.

5. Use direct observation

Whenever possible, directly observe clinical care, particularly a patient’s intake. To reduce trainee (and patient) anxiety and preserve independence, state, “I’m the attending physician supervising Dr. (NAME), who will be your doctor. We provide feedback to trainees right up to graduation so I’m here to observe and will be quiet in the background.” While direct observation is associated with early learners and inpatient settings, it is also preferred by senior outpatient psychiatry residents4 and associated with positive educational and patient outcomes.5

6. Offer supplemental experiences

If feasible, offer additional interdisciplinary supervision (eg, social workers, psychologists, or peer support), scholarly opportunities (eg, case report collaboration or clinic talk), psychotherapy cases, or meeting with patients on your caseload (eg, patients with a rare diagnosis or unique presentation). These align with ACGME’s broad supervision requirements and offer much-appreciated individualized learning tailored to the trainee.

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency). Updated July 1, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf

2. Newman M, Ravindranath D, Figueroa S, et al. Perceptions of supervision in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):153-156. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0191-y

3. The Joint Commission. Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentinel Event Alert. Issue 58. September 12, 2017. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_58_hand_off_comms_9_6_17_final_(1).pdf

4. Tan LL, Kam CJW. How psychiatry residents perceive clinical teaching effectiveness with or without direct supervision. The Asia-Pacific Scholar. 2020;5(2):14-21.

5. Galanter CA, Nikolov R, Green N, et al. Direct supervision in outpatient psychiatric graduate medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):157-163. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0247-z

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires supervision of residents “provides safe and effective care to patients; ensures each resident’s development of the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to enter the unsupervised practice of medicine; and establishes a foundation for continued professional growth.”1 Beyond delineating supervision types (direct, indirect, or oversight), best practices for outpatient supervision are lacking, which perhaps contributes to challenges and discrepancies in experiences involving both trainees and supervisors.2 In this article, I provide 6 practical recommendations for supervisors to address and overcome these challenges.

1. Don’t skip orientation

Resist the pressure to jump directly into clinical care. Devote the first supervision session to learner orientation about expectations (eg, documentation and between-visit patient outreach), logistics (eg, electronic health record or absences), clinic workflow and processes (eg, no-shows or referrals), and team members. Provide this verbally and in writing; the former fosters additional discussion and prompts questions, while the latter serves as a useful reference.

2. Plan for the end at the beginning

Plan ahead for end-of-rotation issues (eg, transfers of care or clinician sign-out), particularly because handoffs are known patient safety risks.3 Provide a written sign-out template or example, set a deadline for the first draft, and ensure known verbal sign-out occurs to both you and any trainees coming into the rotation.

3. Facilitate self-identification of strengths, weaknesses, and goals

Individual learning plans (ILPs) are a fundamental component of adult learning theory, allowing for self-directed learning and ongoing assessment by trainee and supervisor. Complete the ILP together at the beginning of the rotation and regularly devote time to revisit and revise it. This process ensures targeted feedback, which will reduce the stress and potential surprises often associated with end-of-rotation evaluations.

4. Consider the homework you assign

Be intentional about assigned readings. Consider their frequency and length, highlight where you want learners to focus, provide self-reflection questions/prompts, and take time to discuss during supervision. If you use a structured curriculum, maintain flexibility so your trainees’ interests, topics arising in real-time clinical care, and relevant in-press articles can be included.

5. Use direct observation

Whenever possible, directly observe clinical care, particularly a patient’s intake. To reduce trainee (and patient) anxiety and preserve independence, state, “I’m the attending physician supervising Dr. (NAME), who will be your doctor. We provide feedback to trainees right up to graduation so I’m here to observe and will be quiet in the background.” While direct observation is associated with early learners and inpatient settings, it is also preferred by senior outpatient psychiatry residents4 and associated with positive educational and patient outcomes.5

6. Offer supplemental experiences

If feasible, offer additional interdisciplinary supervision (eg, social workers, psychologists, or peer support), scholarly opportunities (eg, case report collaboration or clinic talk), psychotherapy cases, or meeting with patients on your caseload (eg, patients with a rare diagnosis or unique presentation). These align with ACGME’s broad supervision requirements and offer much-appreciated individualized learning tailored to the trainee.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires supervision of residents “provides safe and effective care to patients; ensures each resident’s development of the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to enter the unsupervised practice of medicine; and establishes a foundation for continued professional growth.”1 Beyond delineating supervision types (direct, indirect, or oversight), best practices for outpatient supervision are lacking, which perhaps contributes to challenges and discrepancies in experiences involving both trainees and supervisors.2 In this article, I provide 6 practical recommendations for supervisors to address and overcome these challenges.

1. Don’t skip orientation

Resist the pressure to jump directly into clinical care. Devote the first supervision session to learner orientation about expectations (eg, documentation and between-visit patient outreach), logistics (eg, electronic health record or absences), clinic workflow and processes (eg, no-shows or referrals), and team members. Provide this verbally and in writing; the former fosters additional discussion and prompts questions, while the latter serves as a useful reference.

2. Plan for the end at the beginning

Plan ahead for end-of-rotation issues (eg, transfers of care or clinician sign-out), particularly because handoffs are known patient safety risks.3 Provide a written sign-out template or example, set a deadline for the first draft, and ensure known verbal sign-out occurs to both you and any trainees coming into the rotation.

3. Facilitate self-identification of strengths, weaknesses, and goals

Individual learning plans (ILPs) are a fundamental component of adult learning theory, allowing for self-directed learning and ongoing assessment by trainee and supervisor. Complete the ILP together at the beginning of the rotation and regularly devote time to revisit and revise it. This process ensures targeted feedback, which will reduce the stress and potential surprises often associated with end-of-rotation evaluations.

4. Consider the homework you assign

Be intentional about assigned readings. Consider their frequency and length, highlight where you want learners to focus, provide self-reflection questions/prompts, and take time to discuss during supervision. If you use a structured curriculum, maintain flexibility so your trainees’ interests, topics arising in real-time clinical care, and relevant in-press articles can be included.

5. Use direct observation

Whenever possible, directly observe clinical care, particularly a patient’s intake. To reduce trainee (and patient) anxiety and preserve independence, state, “I’m the attending physician supervising Dr. (NAME), who will be your doctor. We provide feedback to trainees right up to graduation so I’m here to observe and will be quiet in the background.” While direct observation is associated with early learners and inpatient settings, it is also preferred by senior outpatient psychiatry residents4 and associated with positive educational and patient outcomes.5

6. Offer supplemental experiences

If feasible, offer additional interdisciplinary supervision (eg, social workers, psychologists, or peer support), scholarly opportunities (eg, case report collaboration or clinic talk), psychotherapy cases, or meeting with patients on your caseload (eg, patients with a rare diagnosis or unique presentation). These align with ACGME’s broad supervision requirements and offer much-appreciated individualized learning tailored to the trainee.

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency). Updated July 1, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf

2. Newman M, Ravindranath D, Figueroa S, et al. Perceptions of supervision in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):153-156. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0191-y

3. The Joint Commission. Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentinel Event Alert. Issue 58. September 12, 2017. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_58_hand_off_comms_9_6_17_final_(1).pdf

4. Tan LL, Kam CJW. How psychiatry residents perceive clinical teaching effectiveness with or without direct supervision. The Asia-Pacific Scholar. 2020;5(2):14-21.

5. Galanter CA, Nikolov R, Green N, et al. Direct supervision in outpatient psychiatric graduate medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):157-163. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0247-z

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency). Updated July 1, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf

2. Newman M, Ravindranath D, Figueroa S, et al. Perceptions of supervision in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):153-156. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0191-y

3. The Joint Commission. Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentinel Event Alert. Issue 58. September 12, 2017. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_58_hand_off_comms_9_6_17_final_(1).pdf

4. Tan LL, Kam CJW. How psychiatry residents perceive clinical teaching effectiveness with or without direct supervision. The Asia-Pacific Scholar. 2020;5(2):14-21.

5. Galanter CA, Nikolov R, Green N, et al. Direct supervision in outpatient psychiatric graduate medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):157-163. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0247-z

Perinatal psychiatry: 5 key principles

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

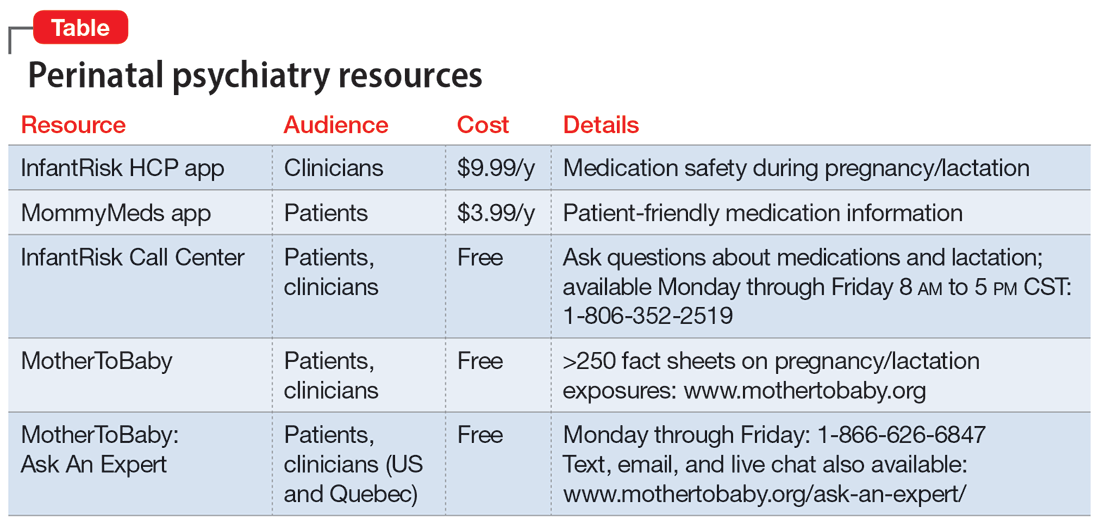

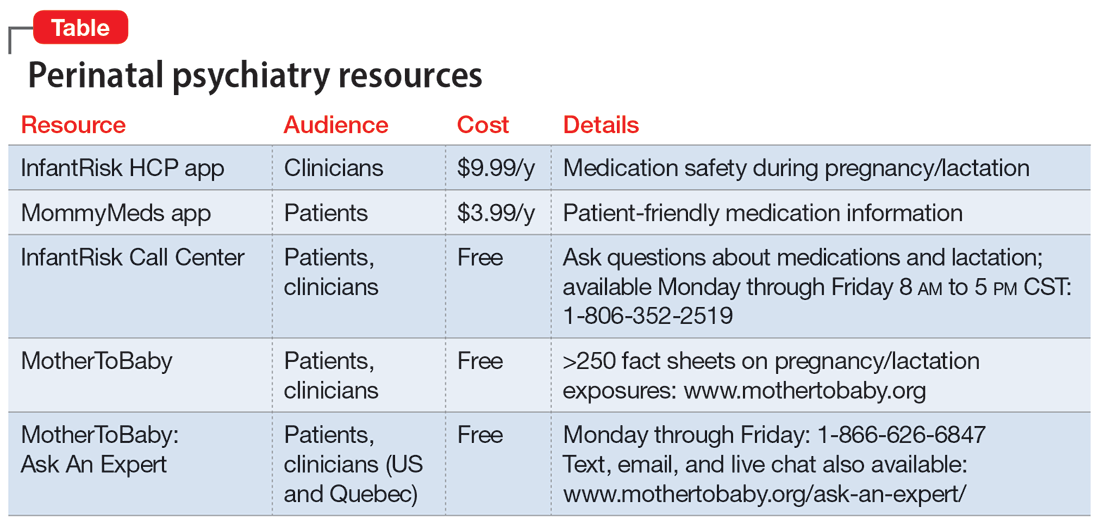

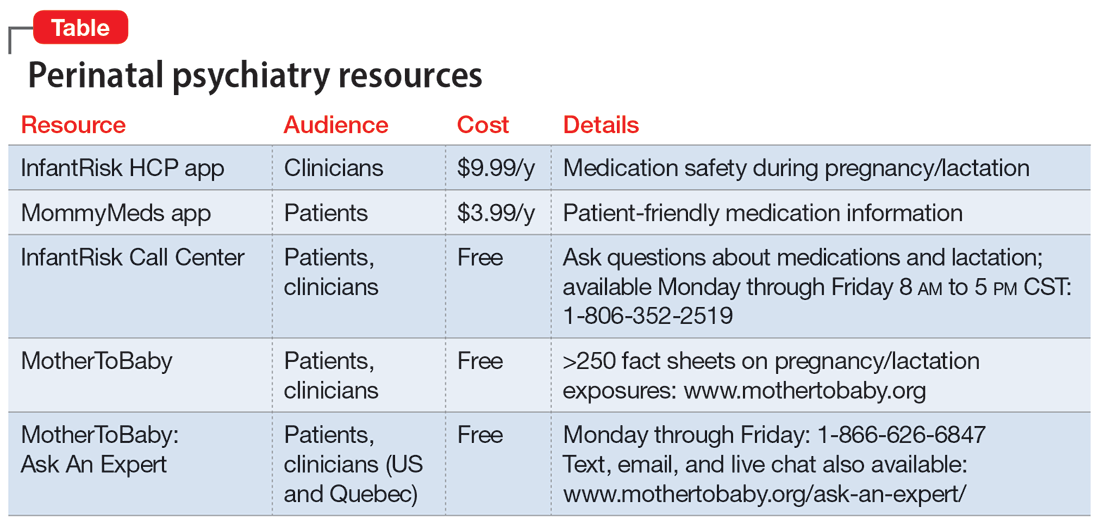

5. Recognize your limitations

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

5. Recognize your limitations

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

5. Recognize your limitations

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

Termination of pregnancy for medical reasons: A mental health perspective

Termination of pregnancy for medical reasons (TFMR) occurs when a pregnancy is ended due to medical complications that threaten the health of a pregnant individual and/or fetus, or when a fetus has a poor prognosis or life-limiting diagnosis. It is distinct from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists identification of all abortions as medically indicated. Common indications for TFMR include life-threatening pregnancy complications (eg, placental abruption, hyperemesis gravidarum, exacerbation of psychiatric illness), chromosomal abnormalities (eg, Trisomy 13, 18, and 21; Klinefelter syndrome), and fetal anomalies (eg, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, renal agenesis). In this article, we discuss the negative psychological outcomes of TFMR, and how to screen and intervene to best help women who experience TFMR.

Psychiatric sequelae of TFMR

Unlike abortions in general, negative psychological outcomes are common among women who experience TFMR.1 Nearly one-half of women develop symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and approximately one-fourth show signs of depression at 4 months after termination.2 Such symptoms usually improve with time but may return around trauma anniversaries (date of diagnosis or termination). Women with a history of trauma, a prior psychiatric diagnosis, and/or no living children are at greater risk. Self-blame, doubt, and high levels of distress are also risk factors.2-4 Protective factors include positive coping strategies (such as acceptance or reframing), higher perceived social support, and high self-efficacy.3,4

Screening: What to ask, and how

Use open-ended questions to ask about a patient’s obstetric history:

- Have you ever been pregnant?

- If you’re comfortable sharing, what were the outcomes of these pregnancies?

If a woman discloses that she has experienced a TFMR, screen for and normalize psychiatric outcomes by asking:

- Symptoms of grief, depression, and anxiety are common after TFMR. Have you experienced such symptoms?

- What impact has terminating your pregnancy for medical reasons had on your mental health?

Screening tools such as the General Self-Efficacy Scale can help assess predictive factors, while other scales can assess specific diagnoses (eg, Patient Health Questionaire-9 for depression, Impact of Event Scale-Revised and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 for trauma-related symptoms, Traumatic Grief Inventory Self Report Version for pathological grief). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale can assess for depression, but if you use this instrument, exclude statements that reference a current pregnancy or recent delivery.

How to best help

Interventions should be specific and targeted. Thus, consider the individual nature of the experience and variation in attachment that can occur over time.5 OB-GYN and perinatal psychiatry clinicians can recommend local resources and support groups that specifically focus on TFMR, rather than on general pregnancy loss. Refer patients to therapists who specialize in pregnancy loss, reproductive trauma, and/or TFMR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy may be appropriate and effective.3 Online support groups (such as Termination of Pregnancy for Medical Reasons; www.facebook.com/groups/TFMRgroup/) can supplement or fill gaps in local resources. Suggest books that discuss TFMR, such

1. González-Ramos Z, Zuriguel-Pérez E, Albacar-Riobóo N, et al. The emotional responses of women when terminating a pregnancy for medical reasons: a scoping review. Midwifery. 2021;103:103095. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2021.103095

2. Korenromp MJ, Page-Christiaens GCML, van den Bout J, et al. Adjustment to termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly: a longitudinal study in women at 4, 8, and 16 months. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(2):160.e1-7.

3. Lafarge C, Mitchell K, Fox P. Perinatal grief following a termination of pregnancy for foetal abnormality: the impact of coping strategies. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(12):1173-1182.

4. Korenromp MJ, Christiaens GC, van den Bout J, et al. Long-term psychological consequences of pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: a cross-sectional study. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25(3):253-260.

5. Lou S, Hvidtjørn D, Jørgensen ML, Vogel I. “I had to think: this is not a child.” A qualitative exploration of how women/couples articulate their relation to the fetus/child following termination of a wanted pregnancy due to Down syndrome. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2021;28:100606. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100606

6. Brooks C (ed.). Our Heartbreaking Choices: Forty-Six Women Share Their Stories of Interrupting a Much-Wanted Pregnancy. iUniverse; 2008.

Termination of pregnancy for medical reasons (TFMR) occurs when a pregnancy is ended due to medical complications that threaten the health of a pregnant individual and/or fetus, or when a fetus has a poor prognosis or life-limiting diagnosis. It is distinct from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists identification of all abortions as medically indicated. Common indications for TFMR include life-threatening pregnancy complications (eg, placental abruption, hyperemesis gravidarum, exacerbation of psychiatric illness), chromosomal abnormalities (eg, Trisomy 13, 18, and 21; Klinefelter syndrome), and fetal anomalies (eg, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, renal agenesis). In this article, we discuss the negative psychological outcomes of TFMR, and how to screen and intervene to best help women who experience TFMR.

Psychiatric sequelae of TFMR

Unlike abortions in general, negative psychological outcomes are common among women who experience TFMR.1 Nearly one-half of women develop symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and approximately one-fourth show signs of depression at 4 months after termination.2 Such symptoms usually improve with time but may return around trauma anniversaries (date of diagnosis or termination). Women with a history of trauma, a prior psychiatric diagnosis, and/or no living children are at greater risk. Self-blame, doubt, and high levels of distress are also risk factors.2-4 Protective factors include positive coping strategies (such as acceptance or reframing), higher perceived social support, and high self-efficacy.3,4

Screening: What to ask, and how

Use open-ended questions to ask about a patient’s obstetric history:

- Have you ever been pregnant?

- If you’re comfortable sharing, what were the outcomes of these pregnancies?

If a woman discloses that she has experienced a TFMR, screen for and normalize psychiatric outcomes by asking:

- Symptoms of grief, depression, and anxiety are common after TFMR. Have you experienced such symptoms?

- What impact has terminating your pregnancy for medical reasons had on your mental health?

Screening tools such as the General Self-Efficacy Scale can help assess predictive factors, while other scales can assess specific diagnoses (eg, Patient Health Questionaire-9 for depression, Impact of Event Scale-Revised and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 for trauma-related symptoms, Traumatic Grief Inventory Self Report Version for pathological grief). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale can assess for depression, but if you use this instrument, exclude statements that reference a current pregnancy or recent delivery.

How to best help

Interventions should be specific and targeted. Thus, consider the individual nature of the experience and variation in attachment that can occur over time.5 OB-GYN and perinatal psychiatry clinicians can recommend local resources and support groups that specifically focus on TFMR, rather than on general pregnancy loss. Refer patients to therapists who specialize in pregnancy loss, reproductive trauma, and/or TFMR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy may be appropriate and effective.3 Online support groups (such as Termination of Pregnancy for Medical Reasons; www.facebook.com/groups/TFMRgroup/) can supplement or fill gaps in local resources. Suggest books that discuss TFMR, such

Termination of pregnancy for medical reasons (TFMR) occurs when a pregnancy is ended due to medical complications that threaten the health of a pregnant individual and/or fetus, or when a fetus has a poor prognosis or life-limiting diagnosis. It is distinct from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists identification of all abortions as medically indicated. Common indications for TFMR include life-threatening pregnancy complications (eg, placental abruption, hyperemesis gravidarum, exacerbation of psychiatric illness), chromosomal abnormalities (eg, Trisomy 13, 18, and 21; Klinefelter syndrome), and fetal anomalies (eg, neural tube defects, cardiac defects, renal agenesis). In this article, we discuss the negative psychological outcomes of TFMR, and how to screen and intervene to best help women who experience TFMR.

Psychiatric sequelae of TFMR

Unlike abortions in general, negative psychological outcomes are common among women who experience TFMR.1 Nearly one-half of women develop symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and approximately one-fourth show signs of depression at 4 months after termination.2 Such symptoms usually improve with time but may return around trauma anniversaries (date of diagnosis or termination). Women with a history of trauma, a prior psychiatric diagnosis, and/or no living children are at greater risk. Self-blame, doubt, and high levels of distress are also risk factors.2-4 Protective factors include positive coping strategies (such as acceptance or reframing), higher perceived social support, and high self-efficacy.3,4

Screening: What to ask, and how

Use open-ended questions to ask about a patient’s obstetric history:

- Have you ever been pregnant?

- If you’re comfortable sharing, what were the outcomes of these pregnancies?

If a woman discloses that she has experienced a TFMR, screen for and normalize psychiatric outcomes by asking:

- Symptoms of grief, depression, and anxiety are common after TFMR. Have you experienced such symptoms?

- What impact has terminating your pregnancy for medical reasons had on your mental health?

Screening tools such as the General Self-Efficacy Scale can help assess predictive factors, while other scales can assess specific diagnoses (eg, Patient Health Questionaire-9 for depression, Impact of Event Scale-Revised and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 for trauma-related symptoms, Traumatic Grief Inventory Self Report Version for pathological grief). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale can assess for depression, but if you use this instrument, exclude statements that reference a current pregnancy or recent delivery.

How to best help

Interventions should be specific and targeted. Thus, consider the individual nature of the experience and variation in attachment that can occur over time.5 OB-GYN and perinatal psychiatry clinicians can recommend local resources and support groups that specifically focus on TFMR, rather than on general pregnancy loss. Refer patients to therapists who specialize in pregnancy loss, reproductive trauma, and/or TFMR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy may be appropriate and effective.3 Online support groups (such as Termination of Pregnancy for Medical Reasons; www.facebook.com/groups/TFMRgroup/) can supplement or fill gaps in local resources. Suggest books that discuss TFMR, such

1. González-Ramos Z, Zuriguel-Pérez E, Albacar-Riobóo N, et al. The emotional responses of women when terminating a pregnancy for medical reasons: a scoping review. Midwifery. 2021;103:103095. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2021.103095

2. Korenromp MJ, Page-Christiaens GCML, van den Bout J, et al. Adjustment to termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly: a longitudinal study in women at 4, 8, and 16 months. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(2):160.e1-7.

3. Lafarge C, Mitchell K, Fox P. Perinatal grief following a termination of pregnancy for foetal abnormality: the impact of coping strategies. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(12):1173-1182.

4. Korenromp MJ, Christiaens GC, van den Bout J, et al. Long-term psychological consequences of pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: a cross-sectional study. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25(3):253-260.

5. Lou S, Hvidtjørn D, Jørgensen ML, Vogel I. “I had to think: this is not a child.” A qualitative exploration of how women/couples articulate their relation to the fetus/child following termination of a wanted pregnancy due to Down syndrome. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2021;28:100606. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100606

6. Brooks C (ed.). Our Heartbreaking Choices: Forty-Six Women Share Their Stories of Interrupting a Much-Wanted Pregnancy. iUniverse; 2008.

1. González-Ramos Z, Zuriguel-Pérez E, Albacar-Riobóo N, et al. The emotional responses of women when terminating a pregnancy for medical reasons: a scoping review. Midwifery. 2021;103:103095. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2021.103095

2. Korenromp MJ, Page-Christiaens GCML, van den Bout J, et al. Adjustment to termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly: a longitudinal study in women at 4, 8, and 16 months. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(2):160.e1-7.

3. Lafarge C, Mitchell K, Fox P. Perinatal grief following a termination of pregnancy for foetal abnormality: the impact of coping strategies. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(12):1173-1182.

4. Korenromp MJ, Christiaens GC, van den Bout J, et al. Long-term psychological consequences of pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: a cross-sectional study. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25(3):253-260.

5. Lou S, Hvidtjørn D, Jørgensen ML, Vogel I. “I had to think: this is not a child.” A qualitative exploration of how women/couples articulate their relation to the fetus/child following termination of a wanted pregnancy due to Down syndrome. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2021;28:100606. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100606

6. Brooks C (ed.). Our Heartbreaking Choices: Forty-Six Women Share Their Stories of Interrupting a Much-Wanted Pregnancy. iUniverse; 2008.

Intimate partner violence: Assessment in the era of telehealth

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner.”1

Ensure a safe environment

At the onset of a telehealth appointment, ask the patient “Who is in the room with you?” If an adult or child age >2 years is present, do not assess for IPV because it may be unsafe for the patient to answer such questions. Encourage the patient to use privacy-enhancing strategies (eg, wearing headphones, going outside, calling from a vehicle). Be flexible; someone may not be able to discuss IPV during an appointment but might be able to at a different time, such as when their partner goes to work. For patients who disclose IPV, identify a word, phrase, or gesture to quickly communicate their partner’s presence or need for immediate help.2 While the “Signal for Help” (ie, thumb first tucked into the palm, then covered with fingers to form a fist) has been developed,3 it is not universally familiar; until then, establish specific communications and preferences with each patient. Include a plan for the patient to abruptly disconnect (eg, “You have the wrong number”) with a pre-determined method of follow-up.

Obtain informed consent

Before asking a patient about IPV, provide psychoeducation about the purpose, including its relationship to one’s health. Acknowledge reasons it may not be safe to provide and/or document answers, and describe limits of confidentiality and local mandated reporting requirements.

Standardize the assessment

Intimate partner violence assessment should be normalized (eg, “Because violence is common, I ask everyone about their relationships”), direct, and well-integrated. Know whether your site uses a specific IPV screening tool, such as the Relationship Health and Safety Screen (RHSS), which is used at the VA; if so, learn and practice asking the specific questions aloud until it feels routine and you can maintain eye contact throughout. Examples of other IPV assessment instruments include the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS); Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS), Partner Violence Screen (PVS), and Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST).4 Pay attention to the populations in which a tool has been studied, any associated copyright fees, and gender-neutral and non-heteronormative language. Avoid asking leading questions (eg, “You’re not being hurt, are you?”) or using charged/interpretable terms (eg, “Is someone abusing you?”).

Document with intention

Use person-centered, recovery-oriented language (eg, someone who experiences or uses IPV) rather than stigmatizing language (eg, victim, batterer, abuser). Describe what happened using the individual’s own words and clearly identify the source of information, witnesses, and any weapons used. Choose nonpejorative language (ie, “states” instead of “claims”). Do not document details of the safety plan in the chart because doing so can compromise safety.

Provide resources and referrals

Regardless of whether a patient consents to screening/documentation or discloses IPV, you should offer universal education, resources, and referrals. Review national contacts (National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233), community agencies (available through www.domesticshelters.org), and suggested safety apps such as myPlan (www.myplanapp.org), but do not send a patient electronic or physical materials without first confirming it is safe to do so. Assess the patient’s interest in legal steps (eg, obtaining a protection order, pressing charges) while recognizing and respecting valid concerns about law enforcement involvement, particularly among the Black community and Black transgender women. Provide options instead of instructions, which will empower patients to choose what is best for their situation, and support their decisions.

1. Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. Intimate partner violence in the United States – 2010. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 2014. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf

2. Evans ML, Lindauer JD, Farrell ME. A pandemic within a pandemic – intimate partner violence during Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2302-2304. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2024046

3. Canadian Women’s Foundation. Signal for help. 2020. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://canadianwomen.org/signal-for-help/

4. Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings: Version 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2007. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner.”1

Ensure a safe environment

At the onset of a telehealth appointment, ask the patient “Who is in the room with you?” If an adult or child age >2 years is present, do not assess for IPV because it may be unsafe for the patient to answer such questions. Encourage the patient to use privacy-enhancing strategies (eg, wearing headphones, going outside, calling from a vehicle). Be flexible; someone may not be able to discuss IPV during an appointment but might be able to at a different time, such as when their partner goes to work. For patients who disclose IPV, identify a word, phrase, or gesture to quickly communicate their partner’s presence or need for immediate help.2 While the “Signal for Help” (ie, thumb first tucked into the palm, then covered with fingers to form a fist) has been developed,3 it is not universally familiar; until then, establish specific communications and preferences with each patient. Include a plan for the patient to abruptly disconnect (eg, “You have the wrong number”) with a pre-determined method of follow-up.

Obtain informed consent

Before asking a patient about IPV, provide psychoeducation about the purpose, including its relationship to one’s health. Acknowledge reasons it may not be safe to provide and/or document answers, and describe limits of confidentiality and local mandated reporting requirements.

Standardize the assessment

Intimate partner violence assessment should be normalized (eg, “Because violence is common, I ask everyone about their relationships”), direct, and well-integrated. Know whether your site uses a specific IPV screening tool, such as the Relationship Health and Safety Screen (RHSS), which is used at the VA; if so, learn and practice asking the specific questions aloud until it feels routine and you can maintain eye contact throughout. Examples of other IPV assessment instruments include the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS); Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS), Partner Violence Screen (PVS), and Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST).4 Pay attention to the populations in which a tool has been studied, any associated copyright fees, and gender-neutral and non-heteronormative language. Avoid asking leading questions (eg, “You’re not being hurt, are you?”) or using charged/interpretable terms (eg, “Is someone abusing you?”).

Document with intention

Use person-centered, recovery-oriented language (eg, someone who experiences or uses IPV) rather than stigmatizing language (eg, victim, batterer, abuser). Describe what happened using the individual’s own words and clearly identify the source of information, witnesses, and any weapons used. Choose nonpejorative language (ie, “states” instead of “claims”). Do not document details of the safety plan in the chart because doing so can compromise safety.

Provide resources and referrals

Regardless of whether a patient consents to screening/documentation or discloses IPV, you should offer universal education, resources, and referrals. Review national contacts (National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233), community agencies (available through www.domesticshelters.org), and suggested safety apps such as myPlan (www.myplanapp.org), but do not send a patient electronic or physical materials without first confirming it is safe to do so. Assess the patient’s interest in legal steps (eg, obtaining a protection order, pressing charges) while recognizing and respecting valid concerns about law enforcement involvement, particularly among the Black community and Black transgender women. Provide options instead of instructions, which will empower patients to choose what is best for their situation, and support their decisions.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner.”1

Ensure a safe environment

At the onset of a telehealth appointment, ask the patient “Who is in the room with you?” If an adult or child age >2 years is present, do not assess for IPV because it may be unsafe for the patient to answer such questions. Encourage the patient to use privacy-enhancing strategies (eg, wearing headphones, going outside, calling from a vehicle). Be flexible; someone may not be able to discuss IPV during an appointment but might be able to at a different time, such as when their partner goes to work. For patients who disclose IPV, identify a word, phrase, or gesture to quickly communicate their partner’s presence or need for immediate help.2 While the “Signal for Help” (ie, thumb first tucked into the palm, then covered with fingers to form a fist) has been developed,3 it is not universally familiar; until then, establish specific communications and preferences with each patient. Include a plan for the patient to abruptly disconnect (eg, “You have the wrong number”) with a pre-determined method of follow-up.

Obtain informed consent

Before asking a patient about IPV, provide psychoeducation about the purpose, including its relationship to one’s health. Acknowledge reasons it may not be safe to provide and/or document answers, and describe limits of confidentiality and local mandated reporting requirements.

Standardize the assessment

Intimate partner violence assessment should be normalized (eg, “Because violence is common, I ask everyone about their relationships”), direct, and well-integrated. Know whether your site uses a specific IPV screening tool, such as the Relationship Health and Safety Screen (RHSS), which is used at the VA; if so, learn and practice asking the specific questions aloud until it feels routine and you can maintain eye contact throughout. Examples of other IPV assessment instruments include the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS); Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS), Partner Violence Screen (PVS), and Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST).4 Pay attention to the populations in which a tool has been studied, any associated copyright fees, and gender-neutral and non-heteronormative language. Avoid asking leading questions (eg, “You’re not being hurt, are you?”) or using charged/interpretable terms (eg, “Is someone abusing you?”).

Document with intention

Use person-centered, recovery-oriented language (eg, someone who experiences or uses IPV) rather than stigmatizing language (eg, victim, batterer, abuser). Describe what happened using the individual’s own words and clearly identify the source of information, witnesses, and any weapons used. Choose nonpejorative language (ie, “states” instead of “claims”). Do not document details of the safety plan in the chart because doing so can compromise safety.

Provide resources and referrals

Regardless of whether a patient consents to screening/documentation or discloses IPV, you should offer universal education, resources, and referrals. Review national contacts (National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233), community agencies (available through www.domesticshelters.org), and suggested safety apps such as myPlan (www.myplanapp.org), but do not send a patient electronic or physical materials without first confirming it is safe to do so. Assess the patient’s interest in legal steps (eg, obtaining a protection order, pressing charges) while recognizing and respecting valid concerns about law enforcement involvement, particularly among the Black community and Black transgender women. Provide options instead of instructions, which will empower patients to choose what is best for their situation, and support their decisions.

1. Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. Intimate partner violence in the United States – 2010. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 2014. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf

2. Evans ML, Lindauer JD, Farrell ME. A pandemic within a pandemic – intimate partner violence during Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2302-2304. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2024046

3. Canadian Women’s Foundation. Signal for help. 2020. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://canadianwomen.org/signal-for-help/

4. Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings: Version 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2007. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf

1. Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. Intimate partner violence in the United States – 2010. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 2014. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf

2. Evans ML, Lindauer JD, Farrell ME. A pandemic within a pandemic – intimate partner violence during Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2302-2304. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2024046

3. Canadian Women’s Foundation. Signal for help. 2020. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://canadianwomen.org/signal-for-help/

4. Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings: Version 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2007. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf