Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

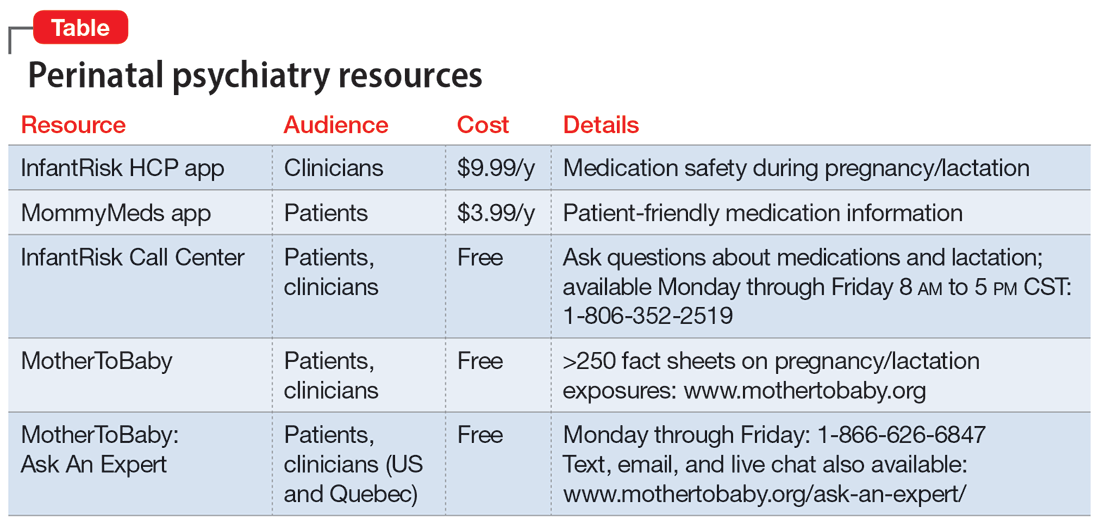

5. Recognize your limitations

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.