User login

Pruritic Axillary Plaques

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

A 42-year-old man presented with pruritic axillary plaques of 6 months’ duration that were exacerbated by heat and friction. He maintained a very active lifestyle and used an antiperspirant regularly. He denied any family history of similar lesions. Thick emollients provided no relief. Physical examination demonstrated numerous soft, hyperkeratotic, waxy, yellowish brown papules coalescing into plaques localized to the bilateral axillary vaults, affecting the right axilla more than the left. Although some papules were firmly adherent to the skin, others were friable and easily removed with a cotton-tipped applicator, revealing an underlying, faintly erythematous base.

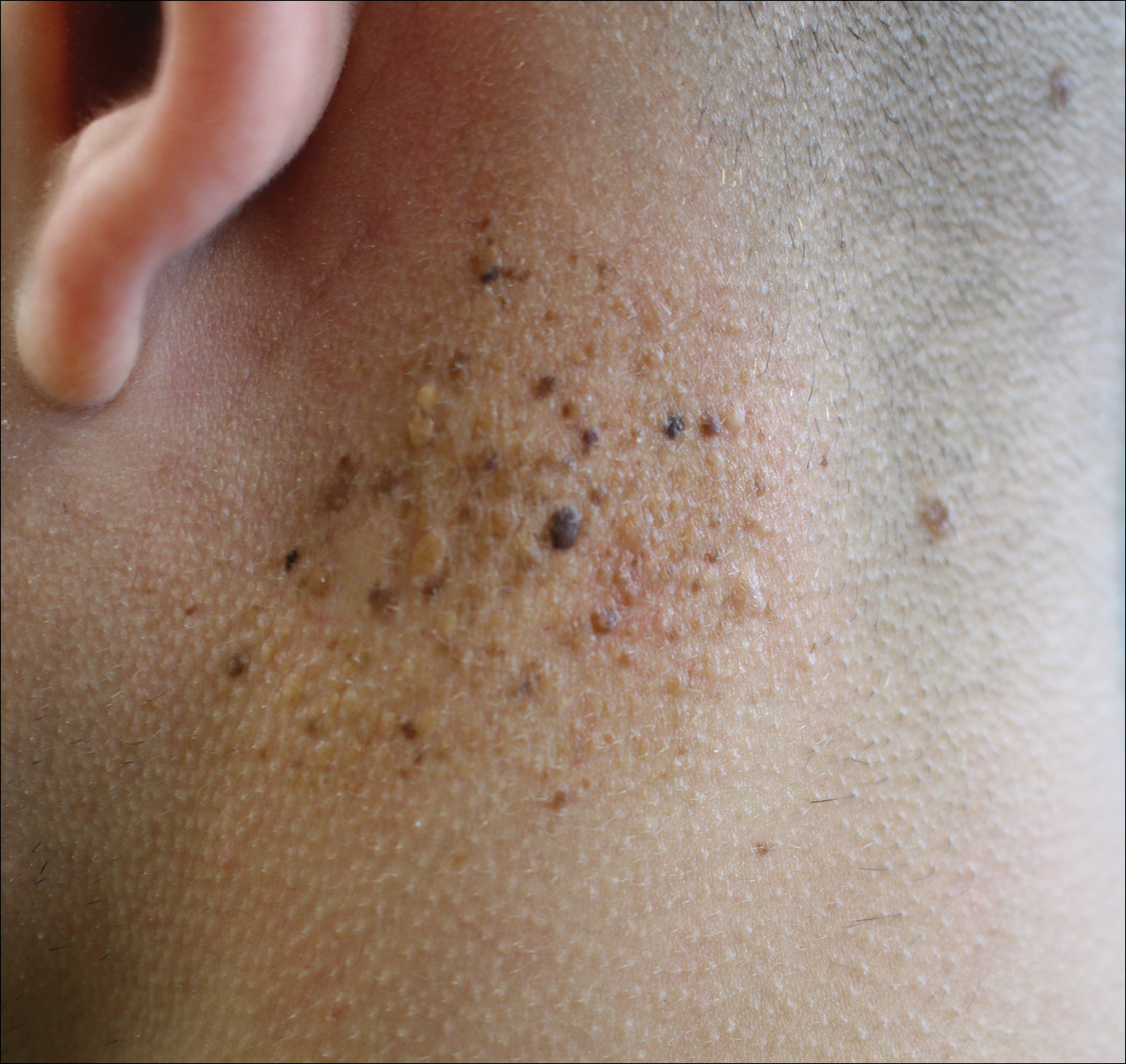

Agminated Heterogeneous Papules on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Blue Nevus

All biopsies demonstrated similar histologic features, including an intradermal proliferation of heavily pigmented, spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes (Figure). The dermal pigment was most pronounced in the grossly darker papules, and there was not a substantial amount of background pigmentation at the stratum basale. Cytologic atypia, foci of necrosis, and mitotic activity were absent from all sections. There was no definitive junctional component identified, no multinucleated giant cells, and there was no overlying epidermal aberration. With some background pigmentation seen histologically, nevus spilus was considered, but because this acute eruption occurred in a young adult without appreciable gross background hyperpigmentation, the clinical context led to a diagnosis of eruptive blue nevus. After communicating the findings to the patient, he declined further treatment.

Eruptive blue nevus is an exceptionally rare subtype of blue nevus with few cases reported since the 1940s.1-9 Generally, each case report found a triggering event that could possibly have precipitated the acute proliferation and evolution of nevi. Triggering events can include bullous processes such as erythema multiforme2 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome,3 severe sunburn,4 trauma,5 immunosuppression,6 and a variety of endocrinopathies. No such history could be identified in our patient, except the biopsy.

Common blue nevi are benign, usually congenital, well-circumscribed, solitary, blue-gray macules or papules. Half of blue nevi cases are found on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet but can present anywhere (eg, face, scalp, wrists, sacrum, buttocks). The blue-gray color appreciated clinically is attributed to the Tyndall effect, which occurs when long-wavelength light--red, orange, and yellow--is absorbed by the melanin deep in the dermis, while short-wavelength visible light--blue, violet, and indigo--is reflected with backscattering. On polarized dermoscopy, a homogeneous blue-gray hue is appreciated, but lighter segments may be present when collagen deposition is robust. Histopathologic findings confirm spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes in the dermis without epidermal involvement. It generally is accepted that the etiology of these benign nevi is a failed migration of neural crest cells to the epidermis.10,11 Although the common blue nevus may be simple to diagnose, several subtypes have been described in the literature, including combined blue nevus, desmoplastic blue nevus, hypomelanotic/amelanotic blue nevus, and epithelioid blue nevus of Carney complex, and excluding a malignant process is of monumental importance.7,12

Biopsy is recommended for common blue nevi in the evaluation of newly acquired lesions, expansion of previously stable nevi, or for nevi larger than 10 mm in diameter. The nature of eruptive blue nevi warrants a biopsy to exclude melanoma or another malignant process. While the Becker nevus may manifest in adolescent males, it is clinically distinct from an eruptive blue nevus due to the size, relative homogeneity, and presence of hair within the lesion. Cutaneous amyloidosis may appear clinically similar to an eruptive blue nevus, but globular or amorphous material was not present in the papillary dermis of biopsied lesions in our patient. Since there was no cellular atypia or mitotic activity, melanoma and other malignancies were ruled out. Lastly, NAME syndrome by definition must include atrial myxomas, myxoid neurofibromas, and ephelides in addition to the nevi; however, our patient had only nevi and few ephelides. Once the diagnosis is established and benign nature confirmed, treatment is not necessarily required. If the patient elects to remove the lesion for aesthetic reasons, an excision into the subcutaneous fat is required to ensure complete removal of deep dermal melanocytes. Prior excisions of eruptive blue nevi have had no recurrence after more than 10 months.8,9

- Krause M, Bonnekoh B, Weisshaar E, et al. Coincidence of multiple, disseminated, tardive-eruptive blue nevi with cutis marmorata teleangiectatica congenita. Dermatology. 2000;200:134-138.

- Soltani K, Bernstein J, Lorincz A. Eruptive nevocytic nevi after erythema multiforme. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:503-505.

- Shoji T, Cockerell C, Koff A, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:337-339.

- Hendricks W. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:50-53.

- Kesty K, Zargari O. Eruptive blue nevi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:198-201.

- Chen T, Kurwa H, Trotter M, et al. Agminated blue nevi in a patient with dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:52-53.

- Walsh M. Correspondence: eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:581-582.

- Nardini P, De Giorgi V, Massi D, et al. Eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:178-180.

- de Giorgi V, Massi D, Brunasso G, et al. Eruptive multiple blue nevi of the penis: a clinical dermoscopic pathologic case study. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:185-188.

- Zimmermann AH, Becker SA. Precursors of epidermal melanocytes in the negro fetus. In: Gordon M, ed. Pigment Cell Biology. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc; 1959:159-170.

- Leopold JG, Richards DB. The interrelationship of blue and common naevi. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1968;95:37-46.

- Zembowicz A, Phadke P. Blue nevi and variants: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:327-336.

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Blue Nevus

All biopsies demonstrated similar histologic features, including an intradermal proliferation of heavily pigmented, spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes (Figure). The dermal pigment was most pronounced in the grossly darker papules, and there was not a substantial amount of background pigmentation at the stratum basale. Cytologic atypia, foci of necrosis, and mitotic activity were absent from all sections. There was no definitive junctional component identified, no multinucleated giant cells, and there was no overlying epidermal aberration. With some background pigmentation seen histologically, nevus spilus was considered, but because this acute eruption occurred in a young adult without appreciable gross background hyperpigmentation, the clinical context led to a diagnosis of eruptive blue nevus. After communicating the findings to the patient, he declined further treatment.

Eruptive blue nevus is an exceptionally rare subtype of blue nevus with few cases reported since the 1940s.1-9 Generally, each case report found a triggering event that could possibly have precipitated the acute proliferation and evolution of nevi. Triggering events can include bullous processes such as erythema multiforme2 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome,3 severe sunburn,4 trauma,5 immunosuppression,6 and a variety of endocrinopathies. No such history could be identified in our patient, except the biopsy.

Common blue nevi are benign, usually congenital, well-circumscribed, solitary, blue-gray macules or papules. Half of blue nevi cases are found on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet but can present anywhere (eg, face, scalp, wrists, sacrum, buttocks). The blue-gray color appreciated clinically is attributed to the Tyndall effect, which occurs when long-wavelength light--red, orange, and yellow--is absorbed by the melanin deep in the dermis, while short-wavelength visible light--blue, violet, and indigo--is reflected with backscattering. On polarized dermoscopy, a homogeneous blue-gray hue is appreciated, but lighter segments may be present when collagen deposition is robust. Histopathologic findings confirm spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes in the dermis without epidermal involvement. It generally is accepted that the etiology of these benign nevi is a failed migration of neural crest cells to the epidermis.10,11 Although the common blue nevus may be simple to diagnose, several subtypes have been described in the literature, including combined blue nevus, desmoplastic blue nevus, hypomelanotic/amelanotic blue nevus, and epithelioid blue nevus of Carney complex, and excluding a malignant process is of monumental importance.7,12

Biopsy is recommended for common blue nevi in the evaluation of newly acquired lesions, expansion of previously stable nevi, or for nevi larger than 10 mm in diameter. The nature of eruptive blue nevi warrants a biopsy to exclude melanoma or another malignant process. While the Becker nevus may manifest in adolescent males, it is clinically distinct from an eruptive blue nevus due to the size, relative homogeneity, and presence of hair within the lesion. Cutaneous amyloidosis may appear clinically similar to an eruptive blue nevus, but globular or amorphous material was not present in the papillary dermis of biopsied lesions in our patient. Since there was no cellular atypia or mitotic activity, melanoma and other malignancies were ruled out. Lastly, NAME syndrome by definition must include atrial myxomas, myxoid neurofibromas, and ephelides in addition to the nevi; however, our patient had only nevi and few ephelides. Once the diagnosis is established and benign nature confirmed, treatment is not necessarily required. If the patient elects to remove the lesion for aesthetic reasons, an excision into the subcutaneous fat is required to ensure complete removal of deep dermal melanocytes. Prior excisions of eruptive blue nevi have had no recurrence after more than 10 months.8,9

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Blue Nevus

All biopsies demonstrated similar histologic features, including an intradermal proliferation of heavily pigmented, spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes (Figure). The dermal pigment was most pronounced in the grossly darker papules, and there was not a substantial amount of background pigmentation at the stratum basale. Cytologic atypia, foci of necrosis, and mitotic activity were absent from all sections. There was no definitive junctional component identified, no multinucleated giant cells, and there was no overlying epidermal aberration. With some background pigmentation seen histologically, nevus spilus was considered, but because this acute eruption occurred in a young adult without appreciable gross background hyperpigmentation, the clinical context led to a diagnosis of eruptive blue nevus. After communicating the findings to the patient, he declined further treatment.

Eruptive blue nevus is an exceptionally rare subtype of blue nevus with few cases reported since the 1940s.1-9 Generally, each case report found a triggering event that could possibly have precipitated the acute proliferation and evolution of nevi. Triggering events can include bullous processes such as erythema multiforme2 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome,3 severe sunburn,4 trauma,5 immunosuppression,6 and a variety of endocrinopathies. No such history could be identified in our patient, except the biopsy.

Common blue nevi are benign, usually congenital, well-circumscribed, solitary, blue-gray macules or papules. Half of blue nevi cases are found on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet but can present anywhere (eg, face, scalp, wrists, sacrum, buttocks). The blue-gray color appreciated clinically is attributed to the Tyndall effect, which occurs when long-wavelength light--red, orange, and yellow--is absorbed by the melanin deep in the dermis, while short-wavelength visible light--blue, violet, and indigo--is reflected with backscattering. On polarized dermoscopy, a homogeneous blue-gray hue is appreciated, but lighter segments may be present when collagen deposition is robust. Histopathologic findings confirm spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes in the dermis without epidermal involvement. It generally is accepted that the etiology of these benign nevi is a failed migration of neural crest cells to the epidermis.10,11 Although the common blue nevus may be simple to diagnose, several subtypes have been described in the literature, including combined blue nevus, desmoplastic blue nevus, hypomelanotic/amelanotic blue nevus, and epithelioid blue nevus of Carney complex, and excluding a malignant process is of monumental importance.7,12

Biopsy is recommended for common blue nevi in the evaluation of newly acquired lesions, expansion of previously stable nevi, or for nevi larger than 10 mm in diameter. The nature of eruptive blue nevi warrants a biopsy to exclude melanoma or another malignant process. While the Becker nevus may manifest in adolescent males, it is clinically distinct from an eruptive blue nevus due to the size, relative homogeneity, and presence of hair within the lesion. Cutaneous amyloidosis may appear clinically similar to an eruptive blue nevus, but globular or amorphous material was not present in the papillary dermis of biopsied lesions in our patient. Since there was no cellular atypia or mitotic activity, melanoma and other malignancies were ruled out. Lastly, NAME syndrome by definition must include atrial myxomas, myxoid neurofibromas, and ephelides in addition to the nevi; however, our patient had only nevi and few ephelides. Once the diagnosis is established and benign nature confirmed, treatment is not necessarily required. If the patient elects to remove the lesion for aesthetic reasons, an excision into the subcutaneous fat is required to ensure complete removal of deep dermal melanocytes. Prior excisions of eruptive blue nevi have had no recurrence after more than 10 months.8,9

- Krause M, Bonnekoh B, Weisshaar E, et al. Coincidence of multiple, disseminated, tardive-eruptive blue nevi with cutis marmorata teleangiectatica congenita. Dermatology. 2000;200:134-138.

- Soltani K, Bernstein J, Lorincz A. Eruptive nevocytic nevi after erythema multiforme. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:503-505.

- Shoji T, Cockerell C, Koff A, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:337-339.

- Hendricks W. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:50-53.

- Kesty K, Zargari O. Eruptive blue nevi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:198-201.

- Chen T, Kurwa H, Trotter M, et al. Agminated blue nevi in a patient with dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:52-53.

- Walsh M. Correspondence: eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:581-582.

- Nardini P, De Giorgi V, Massi D, et al. Eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:178-180.

- de Giorgi V, Massi D, Brunasso G, et al. Eruptive multiple blue nevi of the penis: a clinical dermoscopic pathologic case study. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:185-188.

- Zimmermann AH, Becker SA. Precursors of epidermal melanocytes in the negro fetus. In: Gordon M, ed. Pigment Cell Biology. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc; 1959:159-170.

- Leopold JG, Richards DB. The interrelationship of blue and common naevi. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1968;95:37-46.

- Zembowicz A, Phadke P. Blue nevi and variants: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:327-336.

- Krause M, Bonnekoh B, Weisshaar E, et al. Coincidence of multiple, disseminated, tardive-eruptive blue nevi with cutis marmorata teleangiectatica congenita. Dermatology. 2000;200:134-138.

- Soltani K, Bernstein J, Lorincz A. Eruptive nevocytic nevi after erythema multiforme. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:503-505.

- Shoji T, Cockerell C, Koff A, et al. Eruptive melanocytic nevi after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:337-339.

- Hendricks W. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:50-53.

- Kesty K, Zargari O. Eruptive blue nevi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:198-201.

- Chen T, Kurwa H, Trotter M, et al. Agminated blue nevi in a patient with dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:52-53.

- Walsh M. Correspondence: eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:581-582.

- Nardini P, De Giorgi V, Massi D, et al. Eruptive disseminated blue naevi of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:178-180.

- de Giorgi V, Massi D, Brunasso G, et al. Eruptive multiple blue nevi of the penis: a clinical dermoscopic pathologic case study. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:185-188.

- Zimmermann AH, Becker SA. Precursors of epidermal melanocytes in the negro fetus. In: Gordon M, ed. Pigment Cell Biology. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc; 1959:159-170.

- Leopold JG, Richards DB. The interrelationship of blue and common naevi. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1968;95:37-46.

- Zembowicz A, Phadke P. Blue nevi and variants: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:327-336.

A 19-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of several new dark papules on the neck of 1 year's duration. He denied any personal or family history of skin cancer, cardiac abnormalities, or endocrine dysfunction. He also denied any recent changes in health or use of medication. A biopsy was performed at the site 2 years prior for a single blue nevus, but the patient denied history of other trauma or cutaneous eruptions localized to the area. Physical examination revealed numerous dark brown, blue, white, and flesh-colored papules and macules agminated into a well-circumscribed plaque on the left posterolateral neck without background hyperpigmentation. The total area of the plaque was roughly 3×4 cm. There was no associated edema or erythema. Cardiac murmur, thyromegaly, exophthalmos, neurologic deficits, regional lymphadenopathy, and similar skin findings on other areas of the body were not appreciated. Three scouting punch biopsies were taken of the various morphologies present.