User login

Pruritic Axillary Plaques

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

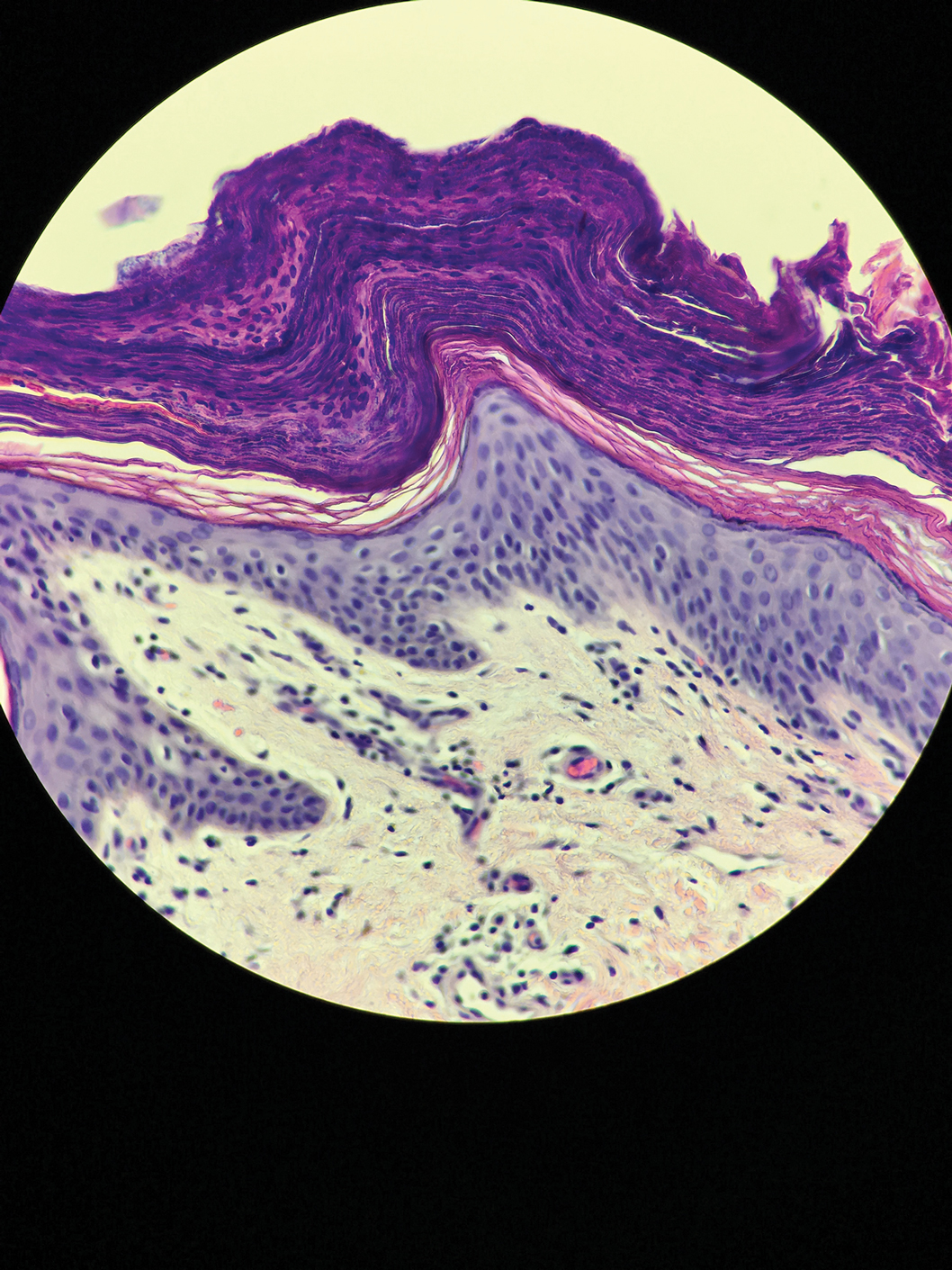

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

A 42-year-old man presented with pruritic axillary plaques of 6 months’ duration that were exacerbated by heat and friction. He maintained a very active lifestyle and used an antiperspirant regularly. He denied any family history of similar lesions. Thick emollients provided no relief. Physical examination demonstrated numerous soft, hyperkeratotic, waxy, yellowish brown papules coalescing into plaques localized to the bilateral axillary vaults, affecting the right axilla more than the left. Although some papules were firmly adherent to the skin, others were friable and easily removed with a cotton-tipped applicator, revealing an underlying, faintly erythematous base.

Stubborn hand rash

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN sought care at our primary care clinic for a stubborn rash that had come on gradually and grown to cover much of his left hand. The rash itched and after much scratching, it began to crack and enlarge. The patient denied any trauma to the hand, but said that the rash was now mildly painful.

The patient indicated that he’d applied a topical antifungal agent to his hand and that the lesion initially shrunk. However, after he stopped using the cream, the rash flared again. He denied any similar lesions on his body, but did note that he occasionally suffered from athlete’s foot. The patient said that he did not wear any rings or gloves regularly. He also denied excessive hand washing.

On examination, I noted a well-circumscribed, dry, flaky, erythematous plaque that extended to the base of each of his 4 fingers (FIGURE 1A). One of the extensions continued to the dorsal side of the middle finger; this area was raised, scaly, and had a scab (FIGURE 1B). The webbing of the fingers was also involved, but the nails were spared.

FIGURE 1

Pruritic rash extends to the dorsal side of the middle finger

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea manuum

This patient was given a diagnosis of tinea manuum, also known as two feet-one hand syndrome, a dermatophyte infection. The patient was initially treating his rash appropriately with the topical antifungal, but failed to treat his concomitant tinea pedis.

The infection is believed to be spread from the feet to the hand by scratching, as tinea pedis or onychomycosis of the toenails precede infection of the hand.1 Whether one is right-handed or left-handed does not appear to play a role in which hand is affected.2,3 However, the hand used to scratch or pick the feet is usually the hand that becomes involved.3,4 The condition is more common in men and it tends to develop at an earlier age in patients who work with their hands.3

Tinea manuum is rare, with occurrence rates ranging from 0.3% to 0.7% of those with superficial fungal infections.5 The true culprit in two feet-one hand syndrome are the feet. Unlike tinea manuum, tinea pedis is the most common fungal skin infection in North America and Europe.6 The most common agents isolated in tinea pedis are Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum.7

The condition presents in one of 4 ways

The differential for two feet-one hand syndrome includes contact dermatitis, an Id reaction (autoeczematization), cellulitis, or a herpetic lesion.2,8

Tinea pedis generally presents in one of 4 ways:1

- Classic ringworm features an erythematous, scaly, well-circumscribed rash on the feet.

- Interdigital tinea pedis has toe web involvement, often between the fourth and fifth toes. It can transition between dry and scaly to soft, soggy, and macerated. Skin may become white and fissures may arise. Pruritus is often worse after the toes dry.

- Moccasin type (plantar hyperkeratotic tinea pedis) features a fine white silvery scale that often covers the entire sole. Skin may be pink and itch. The dorsum of the feet is not usually involved.

- Acute vesicular tinea pedis is a highly inflammatory infection with vesicles that may coalesce into bullae. It likely stems from a chronic infection and is more common when occlusive shoes are worn.

Do a skin scraping

Diagnosis can be easily made with a good history and physical and a potassium hydroxide test. If a scraping from the hand proves to be fungal, a thorough inspection of the feet should be undertaken, as tinea manuum alone is uncommon.

Tx is the same for feet and hand

Topical antifungals such as terbinafine, clotrimazole, or ketoconazole are first-line therapy for the feet and hand.9 Consider oral antifungals if the affected area is large, the patient doesn’t respond to topical therapy, or the patient is immunocompromised.9,10

When oral therapy is initiated for tinea manuum, one week of itraconazole (200 mg twice daily for 7 days) has been shown to be as effective as 2 weeks of oral terbinafine (250 mg daily for 14 days).10

Oral therapy worked for my patient

In light of the patient’s previous failure with topical therapy, he was reluctant to try this approach again. After a normal hepatic panel, I started him on a 2-week course of oral terbinafine 250 mg daily. (Terbinafine was available at our clinic pharmacy, while itraconazole was not). Follow-up at one month showed no sign of previous infection.

CORRESPONDENCE LT Michael Crandall, MD, Department of Dermatology, Naval Medical Center San Diego, 34800 Bob Wilson Drive, San Diego, CA 92134; mikecrandall7@gmail.com

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010:491–540.

2. Wilson M, Bender S, Lynfield Y, et al. Two feet-one hand syndrome. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1988;78:250-253.

3. Daniel CR 3rd, Gupta AK, Daniel MP, et al. Two feet-one hand syndrome: a retrospective multicenter survey. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:658-660.

4. Park BC, Lee SJ, Kim do W, et al. Molecular identification of mycologic correlation in patients with concomitant tinea pedis and tinea manuum infection. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:205-207.

5. Zhan P, Ge YP, Lu XL, et al. A case-control analysis and laboratory study of the two feet-one hand syndrome in two dermatology hospitals in China. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:468-472.

6. Drake LA, Dinehart SM, Farmer ER, et al. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: tinea capitis and tinea barbae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(2 pt 1):290-294.

7. Geary RJ, Lucky AW. Tinea pedis in children presenting as unilateral inflammatory lesions of the sole. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:255-258.

8. Sweeney SM, Wiss K, Mallory SB. Inflammatory tinea pedis/manuum masquerading as bacterial cellulitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1149-1152.

9. Gupta AK, Cooper EA. Update in antifungal therapy of dermatophytosis. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:353-367.

10. Gupta AK, De Doncker P, Degreef H. Tinea manus treated with 1-week itraconazole vs. terbinafine. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:529-531.

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN sought care at our primary care clinic for a stubborn rash that had come on gradually and grown to cover much of his left hand. The rash itched and after much scratching, it began to crack and enlarge. The patient denied any trauma to the hand, but said that the rash was now mildly painful.

The patient indicated that he’d applied a topical antifungal agent to his hand and that the lesion initially shrunk. However, after he stopped using the cream, the rash flared again. He denied any similar lesions on his body, but did note that he occasionally suffered from athlete’s foot. The patient said that he did not wear any rings or gloves regularly. He also denied excessive hand washing.

On examination, I noted a well-circumscribed, dry, flaky, erythematous plaque that extended to the base of each of his 4 fingers (FIGURE 1A). One of the extensions continued to the dorsal side of the middle finger; this area was raised, scaly, and had a scab (FIGURE 1B). The webbing of the fingers was also involved, but the nails were spared.

FIGURE 1

Pruritic rash extends to the dorsal side of the middle finger

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea manuum

This patient was given a diagnosis of tinea manuum, also known as two feet-one hand syndrome, a dermatophyte infection. The patient was initially treating his rash appropriately with the topical antifungal, but failed to treat his concomitant tinea pedis.

The infection is believed to be spread from the feet to the hand by scratching, as tinea pedis or onychomycosis of the toenails precede infection of the hand.1 Whether one is right-handed or left-handed does not appear to play a role in which hand is affected.2,3 However, the hand used to scratch or pick the feet is usually the hand that becomes involved.3,4 The condition is more common in men and it tends to develop at an earlier age in patients who work with their hands.3

Tinea manuum is rare, with occurrence rates ranging from 0.3% to 0.7% of those with superficial fungal infections.5 The true culprit in two feet-one hand syndrome are the feet. Unlike tinea manuum, tinea pedis is the most common fungal skin infection in North America and Europe.6 The most common agents isolated in tinea pedis are Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum.7

The condition presents in one of 4 ways

The differential for two feet-one hand syndrome includes contact dermatitis, an Id reaction (autoeczematization), cellulitis, or a herpetic lesion.2,8

Tinea pedis generally presents in one of 4 ways:1

- Classic ringworm features an erythematous, scaly, well-circumscribed rash on the feet.

- Interdigital tinea pedis has toe web involvement, often between the fourth and fifth toes. It can transition between dry and scaly to soft, soggy, and macerated. Skin may become white and fissures may arise. Pruritus is often worse after the toes dry.

- Moccasin type (plantar hyperkeratotic tinea pedis) features a fine white silvery scale that often covers the entire sole. Skin may be pink and itch. The dorsum of the feet is not usually involved.

- Acute vesicular tinea pedis is a highly inflammatory infection with vesicles that may coalesce into bullae. It likely stems from a chronic infection and is more common when occlusive shoes are worn.

Do a skin scraping

Diagnosis can be easily made with a good history and physical and a potassium hydroxide test. If a scraping from the hand proves to be fungal, a thorough inspection of the feet should be undertaken, as tinea manuum alone is uncommon.

Tx is the same for feet and hand

Topical antifungals such as terbinafine, clotrimazole, or ketoconazole are first-line therapy for the feet and hand.9 Consider oral antifungals if the affected area is large, the patient doesn’t respond to topical therapy, or the patient is immunocompromised.9,10

When oral therapy is initiated for tinea manuum, one week of itraconazole (200 mg twice daily for 7 days) has been shown to be as effective as 2 weeks of oral terbinafine (250 mg daily for 14 days).10

Oral therapy worked for my patient

In light of the patient’s previous failure with topical therapy, he was reluctant to try this approach again. After a normal hepatic panel, I started him on a 2-week course of oral terbinafine 250 mg daily. (Terbinafine was available at our clinic pharmacy, while itraconazole was not). Follow-up at one month showed no sign of previous infection.

CORRESPONDENCE LT Michael Crandall, MD, Department of Dermatology, Naval Medical Center San Diego, 34800 Bob Wilson Drive, San Diego, CA 92134; mikecrandall7@gmail.com

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN sought care at our primary care clinic for a stubborn rash that had come on gradually and grown to cover much of his left hand. The rash itched and after much scratching, it began to crack and enlarge. The patient denied any trauma to the hand, but said that the rash was now mildly painful.

The patient indicated that he’d applied a topical antifungal agent to his hand and that the lesion initially shrunk. However, after he stopped using the cream, the rash flared again. He denied any similar lesions on his body, but did note that he occasionally suffered from athlete’s foot. The patient said that he did not wear any rings or gloves regularly. He also denied excessive hand washing.

On examination, I noted a well-circumscribed, dry, flaky, erythematous plaque that extended to the base of each of his 4 fingers (FIGURE 1A). One of the extensions continued to the dorsal side of the middle finger; this area was raised, scaly, and had a scab (FIGURE 1B). The webbing of the fingers was also involved, but the nails were spared.

FIGURE 1

Pruritic rash extends to the dorsal side of the middle finger

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea manuum

This patient was given a diagnosis of tinea manuum, also known as two feet-one hand syndrome, a dermatophyte infection. The patient was initially treating his rash appropriately with the topical antifungal, but failed to treat his concomitant tinea pedis.

The infection is believed to be spread from the feet to the hand by scratching, as tinea pedis or onychomycosis of the toenails precede infection of the hand.1 Whether one is right-handed or left-handed does not appear to play a role in which hand is affected.2,3 However, the hand used to scratch or pick the feet is usually the hand that becomes involved.3,4 The condition is more common in men and it tends to develop at an earlier age in patients who work with their hands.3

Tinea manuum is rare, with occurrence rates ranging from 0.3% to 0.7% of those with superficial fungal infections.5 The true culprit in two feet-one hand syndrome are the feet. Unlike tinea manuum, tinea pedis is the most common fungal skin infection in North America and Europe.6 The most common agents isolated in tinea pedis are Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum.7

The condition presents in one of 4 ways

The differential for two feet-one hand syndrome includes contact dermatitis, an Id reaction (autoeczematization), cellulitis, or a herpetic lesion.2,8

Tinea pedis generally presents in one of 4 ways:1

- Classic ringworm features an erythematous, scaly, well-circumscribed rash on the feet.

- Interdigital tinea pedis has toe web involvement, often between the fourth and fifth toes. It can transition between dry and scaly to soft, soggy, and macerated. Skin may become white and fissures may arise. Pruritus is often worse after the toes dry.

- Moccasin type (plantar hyperkeratotic tinea pedis) features a fine white silvery scale that often covers the entire sole. Skin may be pink and itch. The dorsum of the feet is not usually involved.

- Acute vesicular tinea pedis is a highly inflammatory infection with vesicles that may coalesce into bullae. It likely stems from a chronic infection and is more common when occlusive shoes are worn.

Do a skin scraping

Diagnosis can be easily made with a good history and physical and a potassium hydroxide test. If a scraping from the hand proves to be fungal, a thorough inspection of the feet should be undertaken, as tinea manuum alone is uncommon.

Tx is the same for feet and hand

Topical antifungals such as terbinafine, clotrimazole, or ketoconazole are first-line therapy for the feet and hand.9 Consider oral antifungals if the affected area is large, the patient doesn’t respond to topical therapy, or the patient is immunocompromised.9,10

When oral therapy is initiated for tinea manuum, one week of itraconazole (200 mg twice daily for 7 days) has been shown to be as effective as 2 weeks of oral terbinafine (250 mg daily for 14 days).10

Oral therapy worked for my patient

In light of the patient’s previous failure with topical therapy, he was reluctant to try this approach again. After a normal hepatic panel, I started him on a 2-week course of oral terbinafine 250 mg daily. (Terbinafine was available at our clinic pharmacy, while itraconazole was not). Follow-up at one month showed no sign of previous infection.

CORRESPONDENCE LT Michael Crandall, MD, Department of Dermatology, Naval Medical Center San Diego, 34800 Bob Wilson Drive, San Diego, CA 92134; mikecrandall7@gmail.com

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010:491–540.

2. Wilson M, Bender S, Lynfield Y, et al. Two feet-one hand syndrome. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1988;78:250-253.

3. Daniel CR 3rd, Gupta AK, Daniel MP, et al. Two feet-one hand syndrome: a retrospective multicenter survey. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:658-660.

4. Park BC, Lee SJ, Kim do W, et al. Molecular identification of mycologic correlation in patients with concomitant tinea pedis and tinea manuum infection. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:205-207.

5. Zhan P, Ge YP, Lu XL, et al. A case-control analysis and laboratory study of the two feet-one hand syndrome in two dermatology hospitals in China. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:468-472.

6. Drake LA, Dinehart SM, Farmer ER, et al. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: tinea capitis and tinea barbae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(2 pt 1):290-294.

7. Geary RJ, Lucky AW. Tinea pedis in children presenting as unilateral inflammatory lesions of the sole. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:255-258.

8. Sweeney SM, Wiss K, Mallory SB. Inflammatory tinea pedis/manuum masquerading as bacterial cellulitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1149-1152.

9. Gupta AK, Cooper EA. Update in antifungal therapy of dermatophytosis. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:353-367.

10. Gupta AK, De Doncker P, Degreef H. Tinea manus treated with 1-week itraconazole vs. terbinafine. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:529-531.

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010:491–540.

2. Wilson M, Bender S, Lynfield Y, et al. Two feet-one hand syndrome. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1988;78:250-253.

3. Daniel CR 3rd, Gupta AK, Daniel MP, et al. Two feet-one hand syndrome: a retrospective multicenter survey. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:658-660.

4. Park BC, Lee SJ, Kim do W, et al. Molecular identification of mycologic correlation in patients with concomitant tinea pedis and tinea manuum infection. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:205-207.

5. Zhan P, Ge YP, Lu XL, et al. A case-control analysis and laboratory study of the two feet-one hand syndrome in two dermatology hospitals in China. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:468-472.

6. Drake LA, Dinehart SM, Farmer ER, et al. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: tinea capitis and tinea barbae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(2 pt 1):290-294.

7. Geary RJ, Lucky AW. Tinea pedis in children presenting as unilateral inflammatory lesions of the sole. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:255-258.

8. Sweeney SM, Wiss K, Mallory SB. Inflammatory tinea pedis/manuum masquerading as bacterial cellulitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1149-1152.

9. Gupta AK, Cooper EA. Update in antifungal therapy of dermatophytosis. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:353-367.

10. Gupta AK, De Doncker P, Degreef H. Tinea manus treated with 1-week itraconazole vs. terbinafine. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:529-531.