User login

Spiral Plaque on the Left Ankle

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

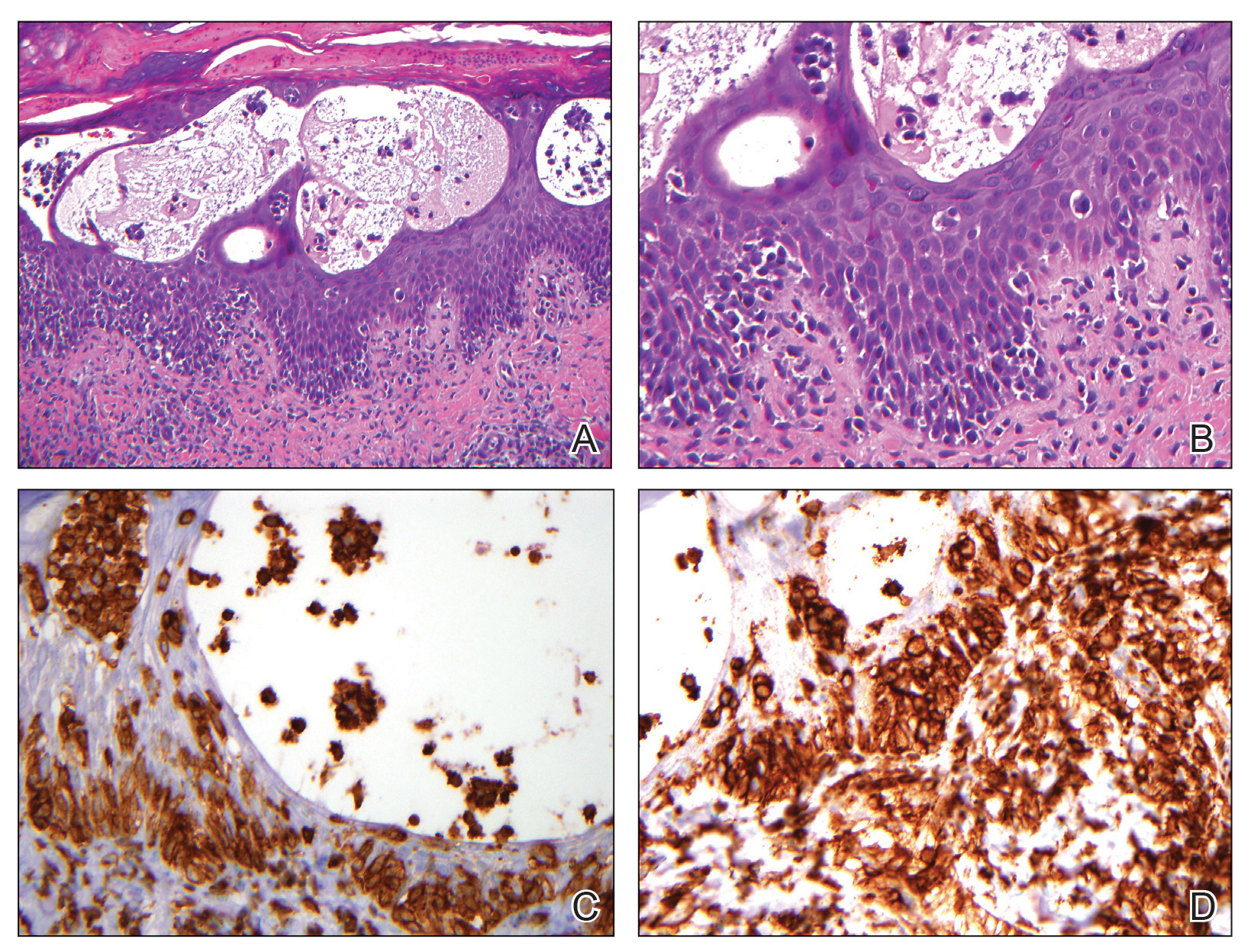

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

A 60-year-old man presented with a whorl-like plaque on the left ankle that he had noticed while undergoing treatment with narrowband UVB every other week and nitrogen mustard gel daily for stage IB cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, mycosis fungoides type. He denied pain, pruritus, and any other associated symptoms at the site. He denied recent illness, new medications, or changes in diet. His medical history included multiple sclerosis, vascular disease, and stroke. Physical examination revealed an 8×6-cm, welldemarcated, slightly scaly, erythematous plaque with a spiral appearance and peripheral hyperpigmentation involving the left ankle. The remainder of the examination was notable for well-controlled mycosis fungoides with several hyperpigmented patches at sites of prior involvement on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and sent for histopathologic examination.

Skin Eruption and Gastrointestinal Symptoms as Presentation of COVID-19

In December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) started an outbreak of respiratory illnesses in Wuhan, China. The respiratory disease was termed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and rapidly spread worldwide, resulting in a pandemic classification on March 11, 2020. 1 Recently, several cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported. Skin manifestations have been reported to be similar to other common viral infections. 2 However, there is a paucity of published clinical images of more atypical presentations.

Case Report

A 52-year-old black man presented via urgent store-and-forward teledermatology consultation from his primary care provider with a self-described “vesicular,” highly pruritic rash of both arms and legs of 1 week’s duration without involvement of the trunk, axillae, groin, face, genitalia, or any mucous membranes. He noted nausea, loss of appetite, and nonbloody diarrhea 4 days later. He denied fever, chills, dry cough, shortness of breath, or dyspnea. He had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. There were no changes in medications; no outdoor activities, gardening, or yard work; no exposure to plants or metals; and no use of new personal care products.

The digital images showed zones of flesh-colored to slightly erythematous, somewhat “juicy” papules with some coalescence into ill-defined plaques. There were scattered foci of scale and hemorrhagic crust that involved both palms, forearms (Figure, A), and legs (Figure, B). There were no intact vesicles, and a herald patch was not identified. Vital signs at the time of imaging were normal, with the exception of a low-grade fever (temperature, 37.3°C). Basic laboratory testing showed only mild leukocytosis with mild neutropenia and mild aspartate aminotransaminase elevation. A skin biopsy was not performed. Pulmonary imaging and workup were not performed because of the lack of respiratory symptoms.

The teledermatology differential diagnosis included a drug eruption, autosensitization eruption, unusual contact dermatitis, viral exanthem, secondary syphilis, and papular pityriasis rosea with an unusual distribution. The absence of changes in the patient’s medication regimen and the lack of outdoor activity in late winter made a drug eruption and contact dermatitis less likely, respectively. A rapid plasma reagin test drawn after disappearance of the rash was negative. Although the morphology of this eruption displayed some features of papular pityriasis rosea, this diagnosis was considered to be less likely given the presence of palmar involvement and the absence of any truncal lesions. This variant of pityriasis rosea is more commonly encountered in younger, darker-skinned patients.

Given the presence of an unusual rash on the extremities followed shortly by gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and coupled with a low-grade fever, a nasopharyngeal swab was obtained to test for COVID-19 using a reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction test. The results were positive.

The patient was treated with triamcinolone 0.1% slush (triamcinolone cream 0.1% mixed 1:1 with tap water) to the affected skin of the extremities 3 times daily, and he experienced a reduction in pruritus. He developed new lesions on the face and eyelids (not imaged) 2 days after teledermatology consultation. The facial involvement was treated with hydrocortisone cream 1%. During the following week, the GI symptoms and skin eruption completely resolved. However, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was observed in areas of the resolved papules and plaques. Over the course of this illness, the patient reported no respiratory symptoms.

Comment

Coronavirus disease 2019 is caused by SARS-CoV2, an enveloped, nonsegmented, positive-sense RNA virus of the coronavirus family. It is currently believed that SARS-CoV-2 uses the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor to gain entry into human cells, leading to infection primarily affecting the lower respiratory tract.3 Patients suspected of COVID-19 infection most often present with fever, dry cough, dyspnea, and fatigue, while GI symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are uncommon.4 More recently, several reports describe a variety of skin findings associated with COVID-19. A current theory suggests that the virus does not directly target keratinocytes but triggers a systemic immune response, leading to a diversity of skin morphologies.5 The main types of described cutaneous findings include pseudochilblains, overtly vesicular, urticarial, maculopapular, and livedo/necrosis.6 Others have described petechial7 and papulosquamous eruptions.8 Most of these patients initially presented with typical COVID-19 symptoms and frequently represented more severe cases of the disease. Additionally, the vesicular and papulosquamous eruptions reportedly occurred on the trunk and not the limbs, as in our case.

This confirmed COVID-19–positive patient presented with an ill-defined vesicular and papulosquamous-type eruption on the arms and legs and later developed only mild GI symptoms. By sharing this case, we report yet another skin manifestation of COVID-19 and propose the possible expansion of testing for SARS-CoV-2 in patients presenting with rash and GI symptoms, which holds the potential to increase the identification of COVID-19 in the population, thereby increasing strict contact tracing and slowing the spread of this pandemic.

- Ng OT, Marimuthu K, Chia PY, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among travelers returning from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1476-1478.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E212-E213.

- Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:11.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720.

- Gianotti R, Zerbi P, Dodiuk-Gad RP. Clinical and histopathological study of skin dermatoses in patients affected by COVID-19 infection in the Northern part of Italy. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:141-143.

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71-77.

- Diaz-Guimaraens B, Dominguez-Santas M, Suarez-Valle A, et al. Petechial skin rash associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:820-822.

- Sanchez A, Sohier P, Benghanem S, et al. Digitate papulosquamous eruption associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:819-820.

In December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) started an outbreak of respiratory illnesses in Wuhan, China. The respiratory disease was termed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and rapidly spread worldwide, resulting in a pandemic classification on March 11, 2020. 1 Recently, several cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported. Skin manifestations have been reported to be similar to other common viral infections. 2 However, there is a paucity of published clinical images of more atypical presentations.

Case Report

A 52-year-old black man presented via urgent store-and-forward teledermatology consultation from his primary care provider with a self-described “vesicular,” highly pruritic rash of both arms and legs of 1 week’s duration without involvement of the trunk, axillae, groin, face, genitalia, or any mucous membranes. He noted nausea, loss of appetite, and nonbloody diarrhea 4 days later. He denied fever, chills, dry cough, shortness of breath, or dyspnea. He had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. There were no changes in medications; no outdoor activities, gardening, or yard work; no exposure to plants or metals; and no use of new personal care products.

The digital images showed zones of flesh-colored to slightly erythematous, somewhat “juicy” papules with some coalescence into ill-defined plaques. There were scattered foci of scale and hemorrhagic crust that involved both palms, forearms (Figure, A), and legs (Figure, B). There were no intact vesicles, and a herald patch was not identified. Vital signs at the time of imaging were normal, with the exception of a low-grade fever (temperature, 37.3°C). Basic laboratory testing showed only mild leukocytosis with mild neutropenia and mild aspartate aminotransaminase elevation. A skin biopsy was not performed. Pulmonary imaging and workup were not performed because of the lack of respiratory symptoms.

The teledermatology differential diagnosis included a drug eruption, autosensitization eruption, unusual contact dermatitis, viral exanthem, secondary syphilis, and papular pityriasis rosea with an unusual distribution. The absence of changes in the patient’s medication regimen and the lack of outdoor activity in late winter made a drug eruption and contact dermatitis less likely, respectively. A rapid plasma reagin test drawn after disappearance of the rash was negative. Although the morphology of this eruption displayed some features of papular pityriasis rosea, this diagnosis was considered to be less likely given the presence of palmar involvement and the absence of any truncal lesions. This variant of pityriasis rosea is more commonly encountered in younger, darker-skinned patients.

Given the presence of an unusual rash on the extremities followed shortly by gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and coupled with a low-grade fever, a nasopharyngeal swab was obtained to test for COVID-19 using a reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction test. The results were positive.

The patient was treated with triamcinolone 0.1% slush (triamcinolone cream 0.1% mixed 1:1 with tap water) to the affected skin of the extremities 3 times daily, and he experienced a reduction in pruritus. He developed new lesions on the face and eyelids (not imaged) 2 days after teledermatology consultation. The facial involvement was treated with hydrocortisone cream 1%. During the following week, the GI symptoms and skin eruption completely resolved. However, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was observed in areas of the resolved papules and plaques. Over the course of this illness, the patient reported no respiratory symptoms.

Comment

Coronavirus disease 2019 is caused by SARS-CoV2, an enveloped, nonsegmented, positive-sense RNA virus of the coronavirus family. It is currently believed that SARS-CoV-2 uses the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor to gain entry into human cells, leading to infection primarily affecting the lower respiratory tract.3 Patients suspected of COVID-19 infection most often present with fever, dry cough, dyspnea, and fatigue, while GI symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are uncommon.4 More recently, several reports describe a variety of skin findings associated with COVID-19. A current theory suggests that the virus does not directly target keratinocytes but triggers a systemic immune response, leading to a diversity of skin morphologies.5 The main types of described cutaneous findings include pseudochilblains, overtly vesicular, urticarial, maculopapular, and livedo/necrosis.6 Others have described petechial7 and papulosquamous eruptions.8 Most of these patients initially presented with typical COVID-19 symptoms and frequently represented more severe cases of the disease. Additionally, the vesicular and papulosquamous eruptions reportedly occurred on the trunk and not the limbs, as in our case.

This confirmed COVID-19–positive patient presented with an ill-defined vesicular and papulosquamous-type eruption on the arms and legs and later developed only mild GI symptoms. By sharing this case, we report yet another skin manifestation of COVID-19 and propose the possible expansion of testing for SARS-CoV-2 in patients presenting with rash and GI symptoms, which holds the potential to increase the identification of COVID-19 in the population, thereby increasing strict contact tracing and slowing the spread of this pandemic.

In December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) started an outbreak of respiratory illnesses in Wuhan, China. The respiratory disease was termed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and rapidly spread worldwide, resulting in a pandemic classification on March 11, 2020. 1 Recently, several cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported. Skin manifestations have been reported to be similar to other common viral infections. 2 However, there is a paucity of published clinical images of more atypical presentations.

Case Report

A 52-year-old black man presented via urgent store-and-forward teledermatology consultation from his primary care provider with a self-described “vesicular,” highly pruritic rash of both arms and legs of 1 week’s duration without involvement of the trunk, axillae, groin, face, genitalia, or any mucous membranes. He noted nausea, loss of appetite, and nonbloody diarrhea 4 days later. He denied fever, chills, dry cough, shortness of breath, or dyspnea. He had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. There were no changes in medications; no outdoor activities, gardening, or yard work; no exposure to plants or metals; and no use of new personal care products.

The digital images showed zones of flesh-colored to slightly erythematous, somewhat “juicy” papules with some coalescence into ill-defined plaques. There were scattered foci of scale and hemorrhagic crust that involved both palms, forearms (Figure, A), and legs (Figure, B). There were no intact vesicles, and a herald patch was not identified. Vital signs at the time of imaging were normal, with the exception of a low-grade fever (temperature, 37.3°C). Basic laboratory testing showed only mild leukocytosis with mild neutropenia and mild aspartate aminotransaminase elevation. A skin biopsy was not performed. Pulmonary imaging and workup were not performed because of the lack of respiratory symptoms.

The teledermatology differential diagnosis included a drug eruption, autosensitization eruption, unusual contact dermatitis, viral exanthem, secondary syphilis, and papular pityriasis rosea with an unusual distribution. The absence of changes in the patient’s medication regimen and the lack of outdoor activity in late winter made a drug eruption and contact dermatitis less likely, respectively. A rapid plasma reagin test drawn after disappearance of the rash was negative. Although the morphology of this eruption displayed some features of papular pityriasis rosea, this diagnosis was considered to be less likely given the presence of palmar involvement and the absence of any truncal lesions. This variant of pityriasis rosea is more commonly encountered in younger, darker-skinned patients.

Given the presence of an unusual rash on the extremities followed shortly by gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and coupled with a low-grade fever, a nasopharyngeal swab was obtained to test for COVID-19 using a reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction test. The results were positive.

The patient was treated with triamcinolone 0.1% slush (triamcinolone cream 0.1% mixed 1:1 with tap water) to the affected skin of the extremities 3 times daily, and he experienced a reduction in pruritus. He developed new lesions on the face and eyelids (not imaged) 2 days after teledermatology consultation. The facial involvement was treated with hydrocortisone cream 1%. During the following week, the GI symptoms and skin eruption completely resolved. However, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was observed in areas of the resolved papules and plaques. Over the course of this illness, the patient reported no respiratory symptoms.

Comment

Coronavirus disease 2019 is caused by SARS-CoV2, an enveloped, nonsegmented, positive-sense RNA virus of the coronavirus family. It is currently believed that SARS-CoV-2 uses the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor to gain entry into human cells, leading to infection primarily affecting the lower respiratory tract.3 Patients suspected of COVID-19 infection most often present with fever, dry cough, dyspnea, and fatigue, while GI symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are uncommon.4 More recently, several reports describe a variety of skin findings associated with COVID-19. A current theory suggests that the virus does not directly target keratinocytes but triggers a systemic immune response, leading to a diversity of skin morphologies.5 The main types of described cutaneous findings include pseudochilblains, overtly vesicular, urticarial, maculopapular, and livedo/necrosis.6 Others have described petechial7 and papulosquamous eruptions.8 Most of these patients initially presented with typical COVID-19 symptoms and frequently represented more severe cases of the disease. Additionally, the vesicular and papulosquamous eruptions reportedly occurred on the trunk and not the limbs, as in our case.

This confirmed COVID-19–positive patient presented with an ill-defined vesicular and papulosquamous-type eruption on the arms and legs and later developed only mild GI symptoms. By sharing this case, we report yet another skin manifestation of COVID-19 and propose the possible expansion of testing for SARS-CoV-2 in patients presenting with rash and GI symptoms, which holds the potential to increase the identification of COVID-19 in the population, thereby increasing strict contact tracing and slowing the spread of this pandemic.

- Ng OT, Marimuthu K, Chia PY, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among travelers returning from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1476-1478.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E212-E213.

- Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:11.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720.

- Gianotti R, Zerbi P, Dodiuk-Gad RP. Clinical and histopathological study of skin dermatoses in patients affected by COVID-19 infection in the Northern part of Italy. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:141-143.

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71-77.

- Diaz-Guimaraens B, Dominguez-Santas M, Suarez-Valle A, et al. Petechial skin rash associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:820-822.

- Sanchez A, Sohier P, Benghanem S, et al. Digitate papulosquamous eruption associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:819-820.

- Ng OT, Marimuthu K, Chia PY, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among travelers returning from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1476-1478.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E212-E213.

- Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:11.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720.

- Gianotti R, Zerbi P, Dodiuk-Gad RP. Clinical and histopathological study of skin dermatoses in patients affected by COVID-19 infection in the Northern part of Italy. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:141-143.

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71-77.

- Diaz-Guimaraens B, Dominguez-Santas M, Suarez-Valle A, et al. Petechial skin rash associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:820-822.

- Sanchez A, Sohier P, Benghanem S, et al. Digitate papulosquamous eruption associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:819-820.

Practice Points

- Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) typically present with fever, dry cough, dyspnea, and fatigue, but cutaneous manifestations also have been reported.

- Awareness of atypical presentations of COVID-19, including uncommon cutaneous manifestations, may identify more cases and help slow the expansion of this pandemic.