User login

Spiral Plaque on the Left Ankle

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

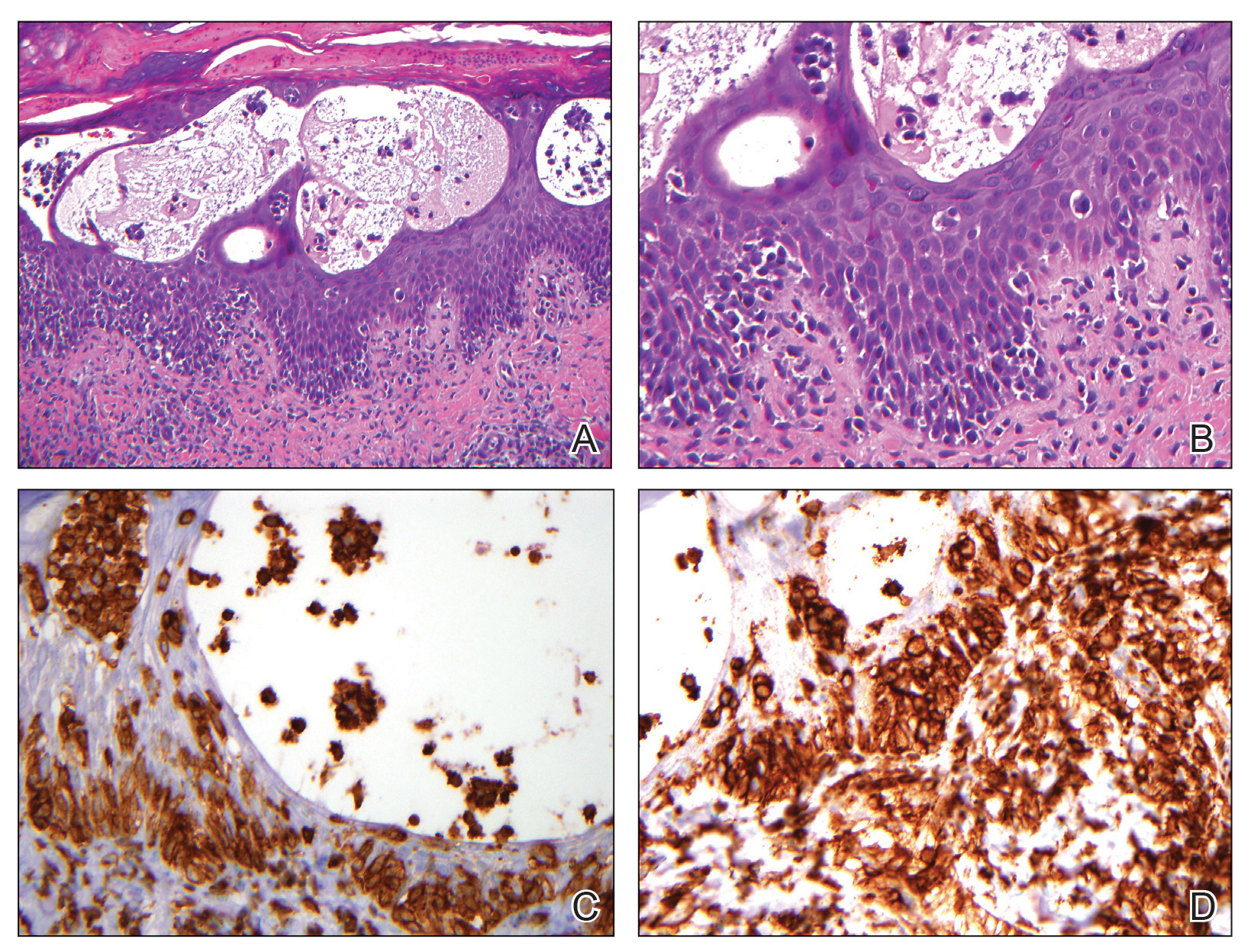

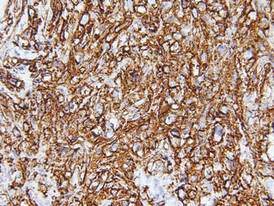

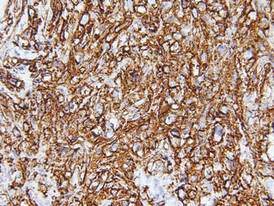

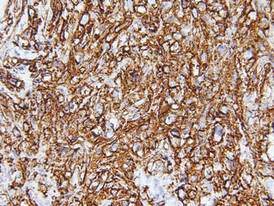

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

A 60-year-old man presented with a whorl-like plaque on the left ankle that he had noticed while undergoing treatment with narrowband UVB every other week and nitrogen mustard gel daily for stage IB cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, mycosis fungoides type. He denied pain, pruritus, and any other associated symptoms at the site. He denied recent illness, new medications, or changes in diet. His medical history included multiple sclerosis, vascular disease, and stroke. Physical examination revealed an 8×6-cm, welldemarcated, slightly scaly, erythematous plaque with a spiral appearance and peripheral hyperpigmentation involving the left ankle. The remainder of the examination was notable for well-controlled mycosis fungoides with several hyperpigmented patches at sites of prior involvement on the trunk and upper and lower extremities. No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and sent for histopathologic examination.

Brown-Black Papulonodules on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.

- Spoerke DG, Spoerke SE. Granuloma formation induced by spines of the cactus, Opuntia acanthocarpa. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:342-344.

- Madkan VK, Abraham T, Lesher JL Jr. Cactus spine granuloma. Cutis. 2007;79:208-210.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- McGovern TW, Barkley TM. Botanical dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:321-334.

- Lindsey D, Lindsey WE. Cactus spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:362-369.

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.

- Spoerke DG, Spoerke SE. Granuloma formation induced by spines of the cactus, Opuntia acanthocarpa. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:342-344.

- Madkan VK, Abraham T, Lesher JL Jr. Cactus spine granuloma. Cutis. 2007;79:208-210.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- McGovern TW, Barkley TM. Botanical dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:321-334.

- Lindsey D, Lindsey WE. Cactus spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:362-369.

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.

- Spoerke DG, Spoerke SE. Granuloma formation induced by spines of the cactus, Opuntia acanthocarpa. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:342-344.

- Madkan VK, Abraham T, Lesher JL Jr. Cactus spine granuloma. Cutis. 2007;79:208-210.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- McGovern TW, Barkley TM. Botanical dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:321-334.

- Lindsey D, Lindsey WE. Cactus spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:362-369.

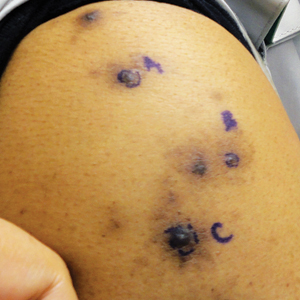

A 63-year-old man presented with a pruritic rash on the right arm of approximately 3 months' duration. On physical examination, several discrete, 4- to 5-mm, brown-black papulonodules with a central punctum were identified along the extensor aspects of the upper and lower right arm. No foreign bodies were appreciated. Biopsies of nodules on the right upper arm were performed (sites marked with letters).

What Is Your Diagnosis? Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

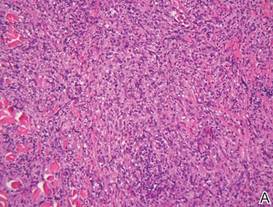

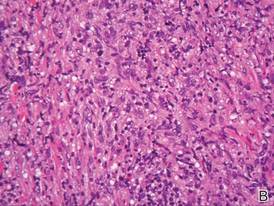

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7

The natural history and therapeutic options differ greatly between subtypes of CBCL. For example, the prognosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is generally favorable with a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of roughly 95%, and radiation therapy is recommended as a first-line therapy for localized disease.2,8 Conversely, primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) frequently spreads to extracutaneous sites8 and carries a much lower estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 55%.2 Chemotherapy with R-CHOP is typically included in initial therapy for primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).8 The prognosis of systemic B-cell lymphomas also is highly variable and may depend on the type of B-cell lymphoma, the stage of disease at diagnosis, histologic and immunologic characteristics, and the therapy received. Wright et al9 reported that patients with systemic germinal center B cell–like DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 62%, whereas patients with activated B cell–like variants of DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 26%. Expression of CD40 may be a favorable prognostic factor following treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with DLBCL,10 whereas FOXP1 protein overexpression is correlated with poor disease-specific survival in certain DLBCL phenotypes.11

Although it is uncertain whether the cutaneous lesions preceded systemic disease in our patient, the cutaneous lesions could be arbitrarily classified as secondary because extracutaneous disease was discovered within 6 months of the initial diagnosis.1 However, classifying the CBCL as primary or secondary did not alter the course of treatment in our patient, as the presumed systemic disease necessitated treatment with systemic chemotherapy; both PCBCLs that develop systemic involvement and SCBCLs (primary extracutaneous disease) usually are treated with systemic chemotherapy. Our case highlights the importance of whole-body staging, as PET-CT scanning changed the course of care by detecting osseous involvement, necessitating systemic therapy as opposed to local radiation therapy alone. A multidisciplinary team with a focus on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous lymphomas helped streamline our patient’s laboratory testing and imaging studies, diagnostic and therapeutic decision making, and treatment implementation. Open channels and frequent opportunities for communication among dermatologists, dermatopathologists, medical oncologists, hematopathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists are needed to optimize and coordinate care for patients with cutaneous lymphoma who require transdisciplinary care.

Acknowledgement—The authors would like to thank Henry Koon, MD (hematology/oncology), for his input and expertise.

1. Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Blood. 1997;90:354-371.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

4. Quereux G, Frot AS, Brocard A, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy in the initial evaluation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma does not appear justified. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:216-220.

5. Senff NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Willemze R. Results of bone marrow examination in 275 patients with histological features that suggest an indolent type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:52-56.

6. Gilliam AC, Wood GS. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:133-141.

7. Burg G, Kempf W, Cozzio A, et al. WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas 2005: histological and molecular aspects. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:647-674.

8. Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600-1609.

9. Wright G, Tan B, Rosenwald A, et al. A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9991-9996.

10. Rydström K, Linderoth J, Nyman H, et al. CD40 is a potential marker of favorable prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1643-1648.

11. Hoeller S, Schneider A, Haralambieva E, et al. FOXP1 protein overexpression is associated with inferior outcome in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with non-gerzminal centre phenotype, independent of gains and structural aberrations at 3p14.1. Histopathology. 2010;57:73-80.

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7

The natural history and therapeutic options differ greatly between subtypes of CBCL. For example, the prognosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is generally favorable with a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of roughly 95%, and radiation therapy is recommended as a first-line therapy for localized disease.2,8 Conversely, primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) frequently spreads to extracutaneous sites8 and carries a much lower estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 55%.2 Chemotherapy with R-CHOP is typically included in initial therapy for primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).8 The prognosis of systemic B-cell lymphomas also is highly variable and may depend on the type of B-cell lymphoma, the stage of disease at diagnosis, histologic and immunologic characteristics, and the therapy received. Wright et al9 reported that patients with systemic germinal center B cell–like DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 62%, whereas patients with activated B cell–like variants of DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 26%. Expression of CD40 may be a favorable prognostic factor following treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with DLBCL,10 whereas FOXP1 protein overexpression is correlated with poor disease-specific survival in certain DLBCL phenotypes.11

Although it is uncertain whether the cutaneous lesions preceded systemic disease in our patient, the cutaneous lesions could be arbitrarily classified as secondary because extracutaneous disease was discovered within 6 months of the initial diagnosis.1 However, classifying the CBCL as primary or secondary did not alter the course of treatment in our patient, as the presumed systemic disease necessitated treatment with systemic chemotherapy; both PCBCLs that develop systemic involvement and SCBCLs (primary extracutaneous disease) usually are treated with systemic chemotherapy. Our case highlights the importance of whole-body staging, as PET-CT scanning changed the course of care by detecting osseous involvement, necessitating systemic therapy as opposed to local radiation therapy alone. A multidisciplinary team with a focus on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous lymphomas helped streamline our patient’s laboratory testing and imaging studies, diagnostic and therapeutic decision making, and treatment implementation. Open channels and frequent opportunities for communication among dermatologists, dermatopathologists, medical oncologists, hematopathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists are needed to optimize and coordinate care for patients with cutaneous lymphoma who require transdisciplinary care.

Acknowledgement—The authors would like to thank Henry Koon, MD (hematology/oncology), for his input and expertise.

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7

The natural history and therapeutic options differ greatly between subtypes of CBCL. For example, the prognosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is generally favorable with a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of roughly 95%, and radiation therapy is recommended as a first-line therapy for localized disease.2,8 Conversely, primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) frequently spreads to extracutaneous sites8 and carries a much lower estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 55%.2 Chemotherapy with R-CHOP is typically included in initial therapy for primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).8 The prognosis of systemic B-cell lymphomas also is highly variable and may depend on the type of B-cell lymphoma, the stage of disease at diagnosis, histologic and immunologic characteristics, and the therapy received. Wright et al9 reported that patients with systemic germinal center B cell–like DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 62%, whereas patients with activated B cell–like variants of DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 26%. Expression of CD40 may be a favorable prognostic factor following treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with DLBCL,10 whereas FOXP1 protein overexpression is correlated with poor disease-specific survival in certain DLBCL phenotypes.11

Although it is uncertain whether the cutaneous lesions preceded systemic disease in our patient, the cutaneous lesions could be arbitrarily classified as secondary because extracutaneous disease was discovered within 6 months of the initial diagnosis.1 However, classifying the CBCL as primary or secondary did not alter the course of treatment in our patient, as the presumed systemic disease necessitated treatment with systemic chemotherapy; both PCBCLs that develop systemic involvement and SCBCLs (primary extracutaneous disease) usually are treated with systemic chemotherapy. Our case highlights the importance of whole-body staging, as PET-CT scanning changed the course of care by detecting osseous involvement, necessitating systemic therapy as opposed to local radiation therapy alone. A multidisciplinary team with a focus on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous lymphomas helped streamline our patient’s laboratory testing and imaging studies, diagnostic and therapeutic decision making, and treatment implementation. Open channels and frequent opportunities for communication among dermatologists, dermatopathologists, medical oncologists, hematopathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists are needed to optimize and coordinate care for patients with cutaneous lymphoma who require transdisciplinary care.

Acknowledgement—The authors would like to thank Henry Koon, MD (hematology/oncology), for his input and expertise.

1. Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Blood. 1997;90:354-371.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

4. Quereux G, Frot AS, Brocard A, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy in the initial evaluation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma does not appear justified. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:216-220.

5. Senff NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Willemze R. Results of bone marrow examination in 275 patients with histological features that suggest an indolent type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:52-56.

6. Gilliam AC, Wood GS. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:133-141.

7. Burg G, Kempf W, Cozzio A, et al. WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas 2005: histological and molecular aspects. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:647-674.

8. Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600-1609.

9. Wright G, Tan B, Rosenwald A, et al. A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9991-9996.

10. Rydström K, Linderoth J, Nyman H, et al. CD40 is a potential marker of favorable prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1643-1648.

11. Hoeller S, Schneider A, Haralambieva E, et al. FOXP1 protein overexpression is associated with inferior outcome in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with non-gerzminal centre phenotype, independent of gains and structural aberrations at 3p14.1. Histopathology. 2010;57:73-80.

1. Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Blood. 1997;90:354-371.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

4. Quereux G, Frot AS, Brocard A, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy in the initial evaluation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma does not appear justified. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:216-220.

5. Senff NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Willemze R. Results of bone marrow examination in 275 patients with histological features that suggest an indolent type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:52-56.

6. Gilliam AC, Wood GS. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:133-141.

7. Burg G, Kempf W, Cozzio A, et al. WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas 2005: histological and molecular aspects. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:647-674.

8. Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600-1609.

9. Wright G, Tan B, Rosenwald A, et al. A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9991-9996.

10. Rydström K, Linderoth J, Nyman H, et al. CD40 is a potential marker of favorable prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1643-1648.

11. Hoeller S, Schneider A, Haralambieva E, et al. FOXP1 protein overexpression is associated with inferior outcome in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with non-gerzminal centre phenotype, independent of gains and structural aberrations at 3p14.1. Histopathology. 2010;57:73-80.