User login

Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma Mimicking Folliculitis

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

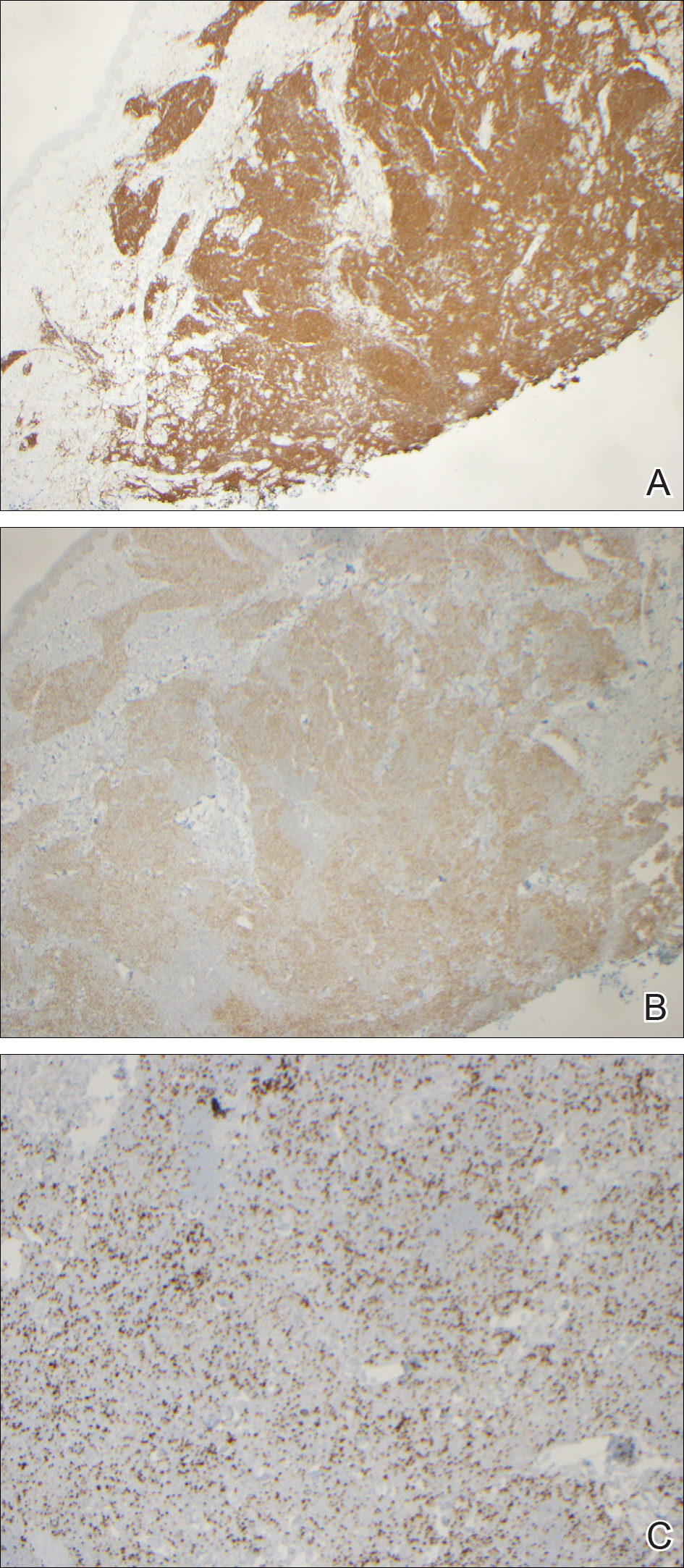

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

Practice Points

- Atypical or unresponsive folliculitis should be biopsied.

- Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma can mimic folliculitis or Grover disease.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

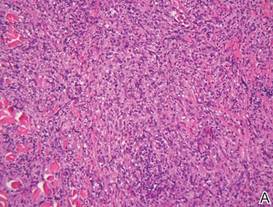

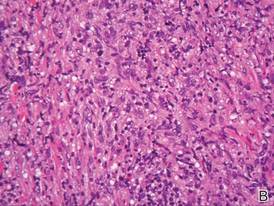

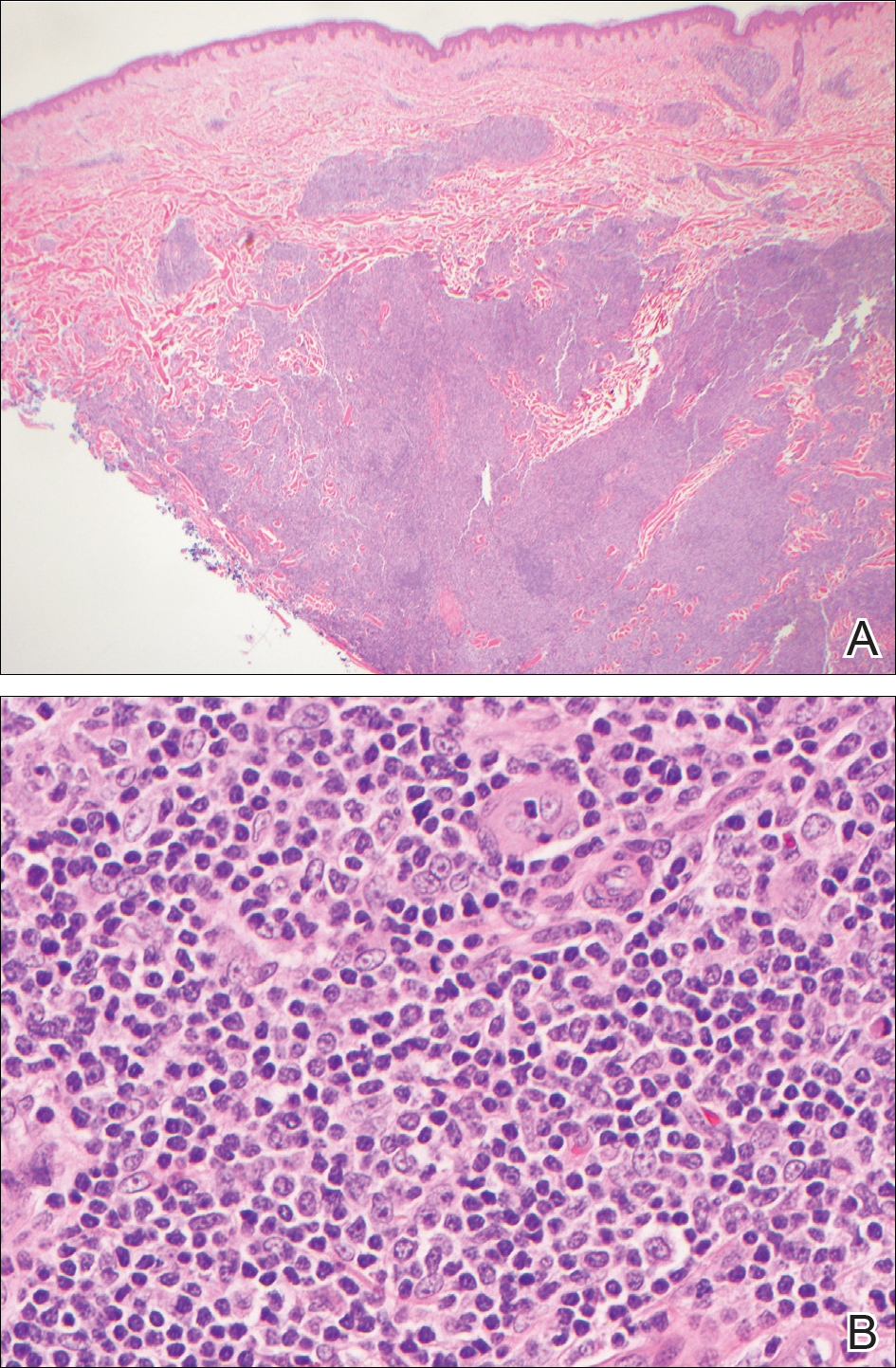

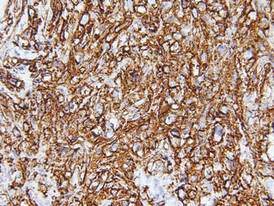

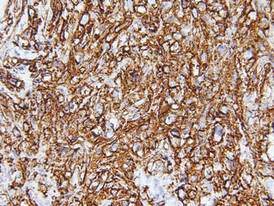

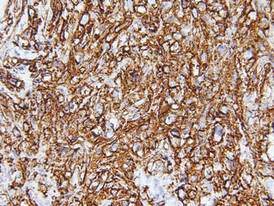

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7

The natural history and therapeutic options differ greatly between subtypes of CBCL. For example, the prognosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is generally favorable with a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of roughly 95%, and radiation therapy is recommended as a first-line therapy for localized disease.2,8 Conversely, primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) frequently spreads to extracutaneous sites8 and carries a much lower estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 55%.2 Chemotherapy with R-CHOP is typically included in initial therapy for primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).8 The prognosis of systemic B-cell lymphomas also is highly variable and may depend on the type of B-cell lymphoma, the stage of disease at diagnosis, histologic and immunologic characteristics, and the therapy received. Wright et al9 reported that patients with systemic germinal center B cell–like DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 62%, whereas patients with activated B cell–like variants of DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 26%. Expression of CD40 may be a favorable prognostic factor following treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with DLBCL,10 whereas FOXP1 protein overexpression is correlated with poor disease-specific survival in certain DLBCL phenotypes.11

Although it is uncertain whether the cutaneous lesions preceded systemic disease in our patient, the cutaneous lesions could be arbitrarily classified as secondary because extracutaneous disease was discovered within 6 months of the initial diagnosis.1 However, classifying the CBCL as primary or secondary did not alter the course of treatment in our patient, as the presumed systemic disease necessitated treatment with systemic chemotherapy; both PCBCLs that develop systemic involvement and SCBCLs (primary extracutaneous disease) usually are treated with systemic chemotherapy. Our case highlights the importance of whole-body staging, as PET-CT scanning changed the course of care by detecting osseous involvement, necessitating systemic therapy as opposed to local radiation therapy alone. A multidisciplinary team with a focus on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous lymphomas helped streamline our patient’s laboratory testing and imaging studies, diagnostic and therapeutic decision making, and treatment implementation. Open channels and frequent opportunities for communication among dermatologists, dermatopathologists, medical oncologists, hematopathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists are needed to optimize and coordinate care for patients with cutaneous lymphoma who require transdisciplinary care.

Acknowledgement—The authors would like to thank Henry Koon, MD (hematology/oncology), for his input and expertise.

1. Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Blood. 1997;90:354-371.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

4. Quereux G, Frot AS, Brocard A, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy in the initial evaluation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma does not appear justified. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:216-220.

5. Senff NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Willemze R. Results of bone marrow examination in 275 patients with histological features that suggest an indolent type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:52-56.

6. Gilliam AC, Wood GS. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:133-141.

7. Burg G, Kempf W, Cozzio A, et al. WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas 2005: histological and molecular aspects. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:647-674.

8. Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600-1609.

9. Wright G, Tan B, Rosenwald A, et al. A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9991-9996.

10. Rydström K, Linderoth J, Nyman H, et al. CD40 is a potential marker of favorable prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1643-1648.

11. Hoeller S, Schneider A, Haralambieva E, et al. FOXP1 protein overexpression is associated with inferior outcome in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with non-gerzminal centre phenotype, independent of gains and structural aberrations at 3p14.1. Histopathology. 2010;57:73-80.

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7

The natural history and therapeutic options differ greatly between subtypes of CBCL. For example, the prognosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is generally favorable with a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of roughly 95%, and radiation therapy is recommended as a first-line therapy for localized disease.2,8 Conversely, primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) frequently spreads to extracutaneous sites8 and carries a much lower estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 55%.2 Chemotherapy with R-CHOP is typically included in initial therapy for primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).8 The prognosis of systemic B-cell lymphomas also is highly variable and may depend on the type of B-cell lymphoma, the stage of disease at diagnosis, histologic and immunologic characteristics, and the therapy received. Wright et al9 reported that patients with systemic germinal center B cell–like DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 62%, whereas patients with activated B cell–like variants of DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 26%. Expression of CD40 may be a favorable prognostic factor following treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with DLBCL,10 whereas FOXP1 protein overexpression is correlated with poor disease-specific survival in certain DLBCL phenotypes.11

Although it is uncertain whether the cutaneous lesions preceded systemic disease in our patient, the cutaneous lesions could be arbitrarily classified as secondary because extracutaneous disease was discovered within 6 months of the initial diagnosis.1 However, classifying the CBCL as primary or secondary did not alter the course of treatment in our patient, as the presumed systemic disease necessitated treatment with systemic chemotherapy; both PCBCLs that develop systemic involvement and SCBCLs (primary extracutaneous disease) usually are treated with systemic chemotherapy. Our case highlights the importance of whole-body staging, as PET-CT scanning changed the course of care by detecting osseous involvement, necessitating systemic therapy as opposed to local radiation therapy alone. A multidisciplinary team with a focus on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous lymphomas helped streamline our patient’s laboratory testing and imaging studies, diagnostic and therapeutic decision making, and treatment implementation. Open channels and frequent opportunities for communication among dermatologists, dermatopathologists, medical oncologists, hematopathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists are needed to optimize and coordinate care for patients with cutaneous lymphoma who require transdisciplinary care.

Acknowledgement—The authors would like to thank Henry Koon, MD (hematology/oncology), for his input and expertise.

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7

The natural history and therapeutic options differ greatly between subtypes of CBCL. For example, the prognosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is generally favorable with a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of roughly 95%, and radiation therapy is recommended as a first-line therapy for localized disease.2,8 Conversely, primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) frequently spreads to extracutaneous sites8 and carries a much lower estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 55%.2 Chemotherapy with R-CHOP is typically included in initial therapy for primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).8 The prognosis of systemic B-cell lymphomas also is highly variable and may depend on the type of B-cell lymphoma, the stage of disease at diagnosis, histologic and immunologic characteristics, and the therapy received. Wright et al9 reported that patients with systemic germinal center B cell–like DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 62%, whereas patients with activated B cell–like variants of DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 26%. Expression of CD40 may be a favorable prognostic factor following treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with DLBCL,10 whereas FOXP1 protein overexpression is correlated with poor disease-specific survival in certain DLBCL phenotypes.11

Although it is uncertain whether the cutaneous lesions preceded systemic disease in our patient, the cutaneous lesions could be arbitrarily classified as secondary because extracutaneous disease was discovered within 6 months of the initial diagnosis.1 However, classifying the CBCL as primary or secondary did not alter the course of treatment in our patient, as the presumed systemic disease necessitated treatment with systemic chemotherapy; both PCBCLs that develop systemic involvement and SCBCLs (primary extracutaneous disease) usually are treated with systemic chemotherapy. Our case highlights the importance of whole-body staging, as PET-CT scanning changed the course of care by detecting osseous involvement, necessitating systemic therapy as opposed to local radiation therapy alone. A multidisciplinary team with a focus on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous lymphomas helped streamline our patient’s laboratory testing and imaging studies, diagnostic and therapeutic decision making, and treatment implementation. Open channels and frequent opportunities for communication among dermatologists, dermatopathologists, medical oncologists, hematopathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists are needed to optimize and coordinate care for patients with cutaneous lymphoma who require transdisciplinary care.

Acknowledgement—The authors would like to thank Henry Koon, MD (hematology/oncology), for his input and expertise.

1. Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Blood. 1997;90:354-371.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

4. Quereux G, Frot AS, Brocard A, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy in the initial evaluation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma does not appear justified. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:216-220.

5. Senff NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Willemze R. Results of bone marrow examination in 275 patients with histological features that suggest an indolent type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:52-56.

6. Gilliam AC, Wood GS. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:133-141.

7. Burg G, Kempf W, Cozzio A, et al. WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas 2005: histological and molecular aspects. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:647-674.

8. Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600-1609.

9. Wright G, Tan B, Rosenwald A, et al. A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9991-9996.

10. Rydström K, Linderoth J, Nyman H, et al. CD40 is a potential marker of favorable prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1643-1648.

11. Hoeller S, Schneider A, Haralambieva E, et al. FOXP1 protein overexpression is associated with inferior outcome in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with non-gerzminal centre phenotype, independent of gains and structural aberrations at 3p14.1. Histopathology. 2010;57:73-80.

1. Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Blood. 1997;90:354-371.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

4. Quereux G, Frot AS, Brocard A, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy in the initial evaluation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma does not appear justified. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:216-220.

5. Senff NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Willemze R. Results of bone marrow examination in 275 patients with histological features that suggest an indolent type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:52-56.

6. Gilliam AC, Wood GS. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:133-141.

7. Burg G, Kempf W, Cozzio A, et al. WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas 2005: histological and molecular aspects. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:647-674.

8. Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600-1609.

9. Wright G, Tan B, Rosenwald A, et al. A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9991-9996.

10. Rydström K, Linderoth J, Nyman H, et al. CD40 is a potential marker of favorable prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1643-1648.

11. Hoeller S, Schneider A, Haralambieva E, et al. FOXP1 protein overexpression is associated with inferior outcome in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with non-gerzminal centre phenotype, independent of gains and structural aberrations at 3p14.1. Histopathology. 2010;57:73-80.