User login

Vesicles and Bullae on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

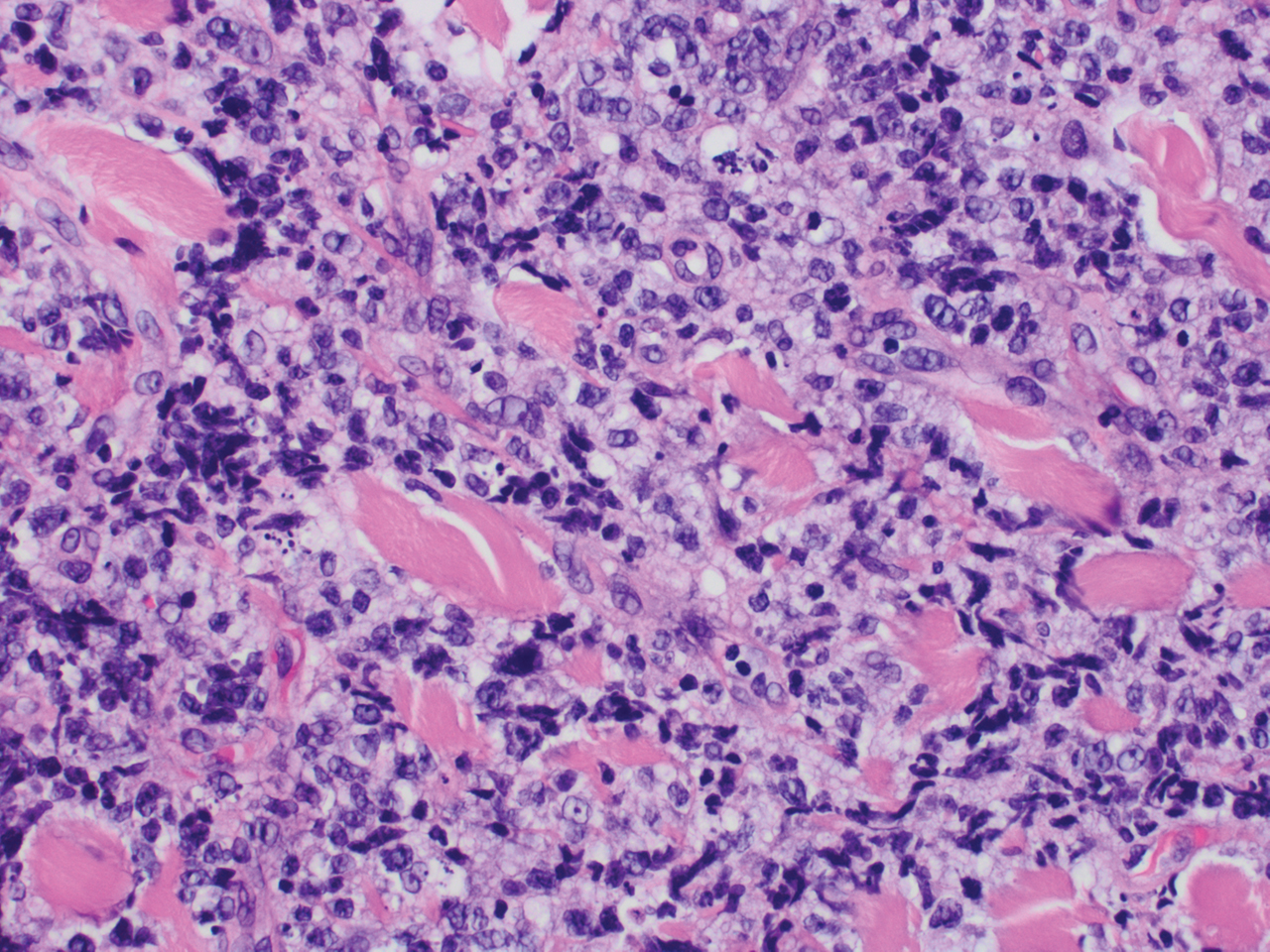

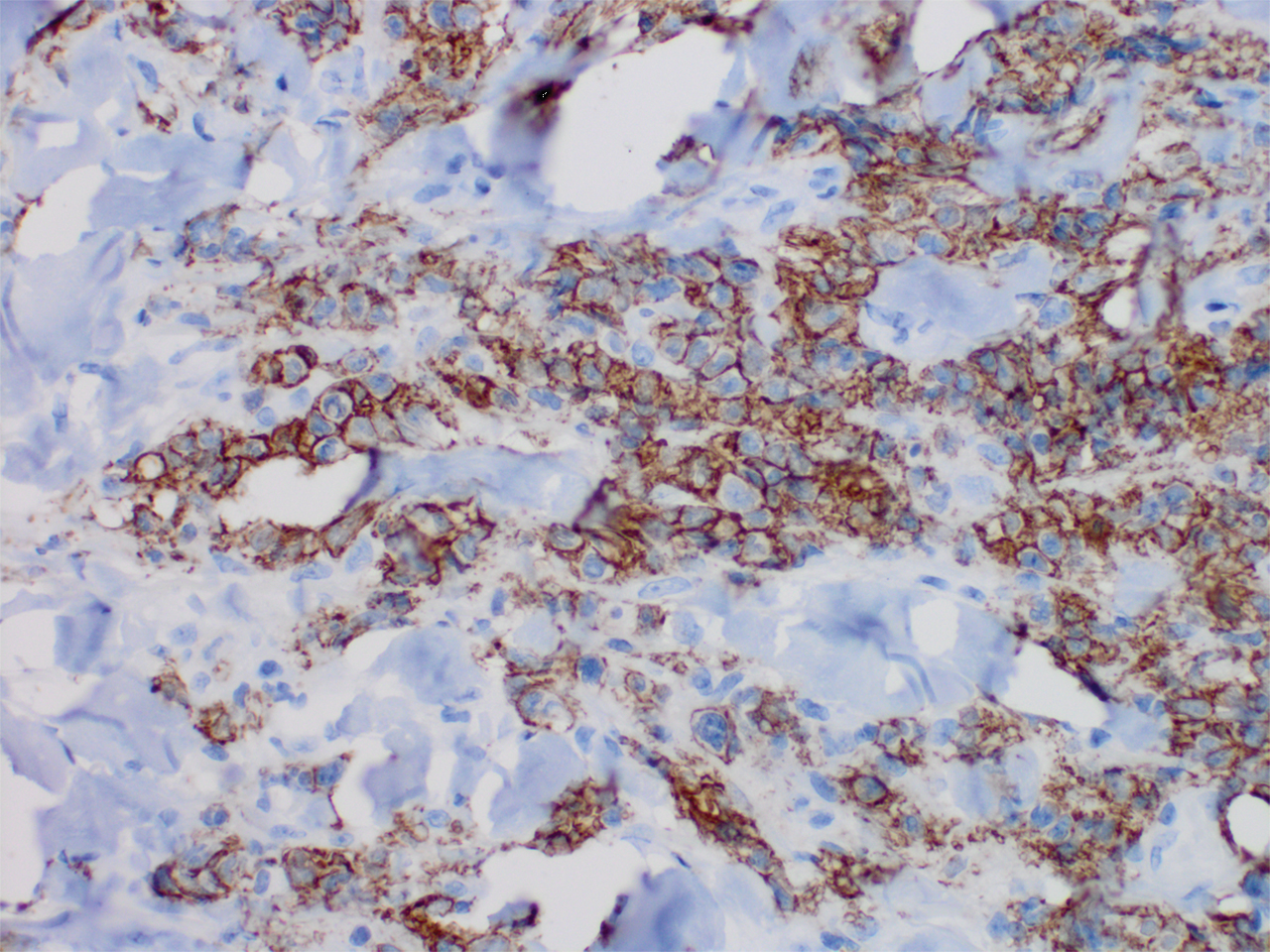

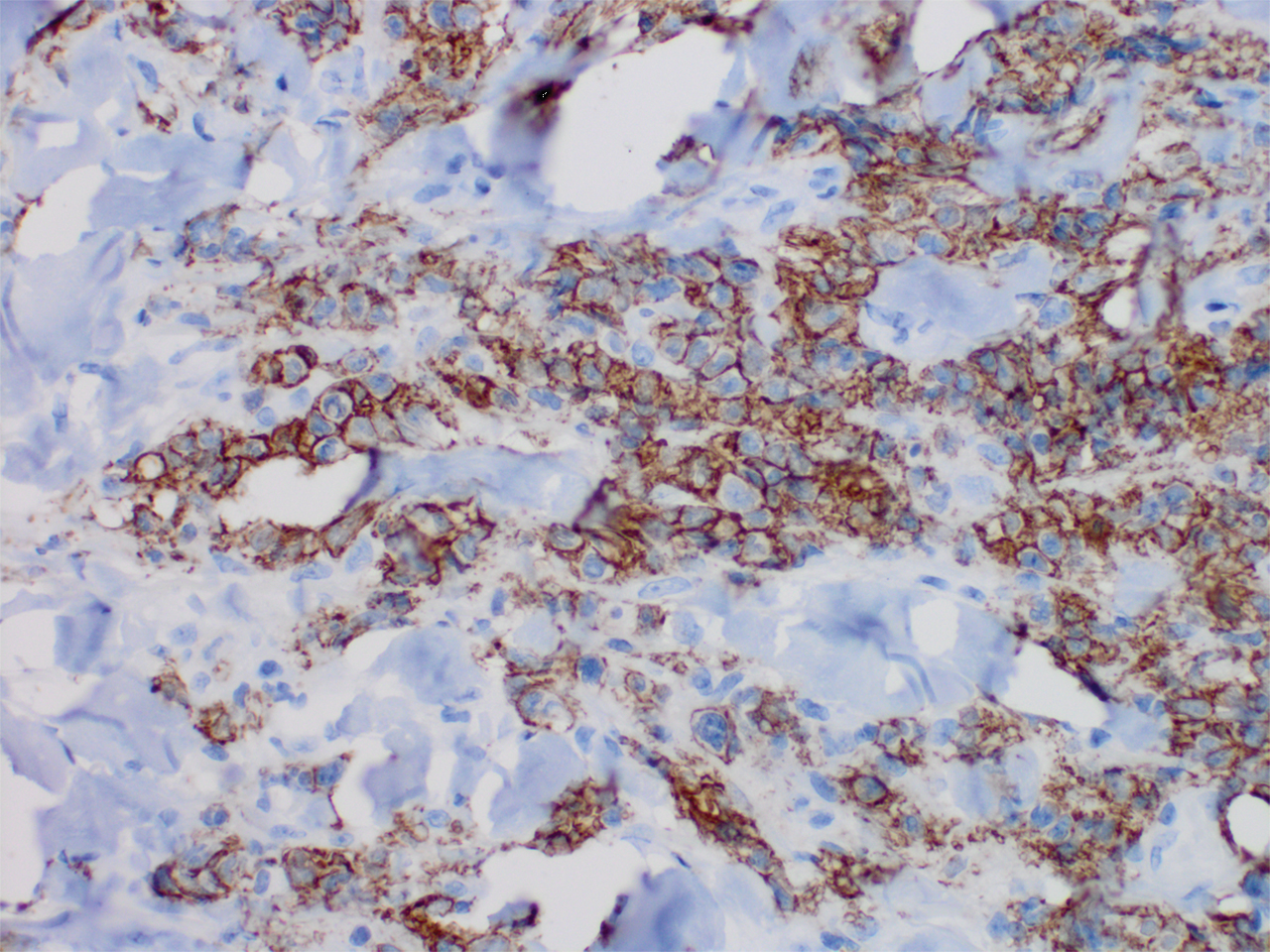

Histopathology revealed a dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis with occasional individual cell necrosis. On closer inspection, the infiltrate consisted of intermediate-sized lymphocytes, some with a vesiculated nucleus and ample amount of cytoplasm, while others contained hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). These cells stained strongly positive for B-cell marker (CD20), while only a few mature lymphocytes demonstrated T-cell phenotype (CD3)(Figure 2).

Although the patient recounted a 3-month history of lower leg edema, he also reported that the rash began a few weeks after his diagnosis of systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma. Throughout this time, he was seen by various physicians who attributed the edema and skin changes to chronic stasis, peripheral venous insufficiency, and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. His primary care physician prescribed an antifungal lotion, which he discontinued on his own due to lack of improvement. Upon arrival to the emergency department, he was started on intravenous cefazolin and subcutaneous heparin. Doppler ultrasonography of the legs was ordered to rule out a deep venous thrombosis. Dermatology was consulted and proceeded with a punch biopsy to investigate for cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (BCL) with a plan to follow up as an outpatient for results upon discharge. He also was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for symptomatic relief.

The patient's left axillary lymph node was biopsied for pathologic evaluation. Immunohistochemical staining revealed expression of B-cell markers CD20, CD79a, and PAX5, along with the antiapoptotic markers BCL-2 and BCL-6. Fluorescence in situ hybridization displayed gene rearrangements of BCL-2, BCL-6, and t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 in the majority of cells. CD3 and CD5 immunostains were negative, indicating that T cells were not involved in this process. Flow cytometry identified a monoclonal κ B-cell population in 40% to 50% of the total cells, which co-expressed CD10, CD19, CD22, and CD38; the cells were negative for CD5, CD20, and CD23. Cell size was variably enlarged and CD71 positive, otherwise known as transferrin receptor 1, indicating the mediation of iron transport into cells of erythroid lineage that is necessary for proliferation.1 Bone marrow core biopsy did not identify features of bone marrow involvement by the lymphoma. Based on these results, the patient was diagnosed with systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma grade 3b stage IIIA. Oncology initiated a systemic chemotherapy regimen with obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine sulfate, and prednisone.

Skin involvement in B-cell follicular lymphoma can be primary or secondary. Although all subtypes of BCL can have secondary cutaneous involvement, it is most common in advanced-stage disease (stages III or IV).2 Cutaneous manifestations of primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma (PCFCL) and systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma secondarily involving the skin can be difficult to distinguish clinically and histopathologically; both appear as solitary or grouped plaques and nodules most commonly on the head, neck, or trunk, and rarely on the legs.3 Although the pathologic features of these two diagnoses can seem almost identical, it is important to differentiate them due to their differing prognosis and management. Patients with follicular lymphoma involving the skin are more likely than those with PCFCL to develop lymphadenopathy and B symptoms.3 Primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma also generally runs an indolent course and requires local therapy, while secondary involvement of the skin due to systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma has a worse prognosis and requires systemic chemotherapy treatment.4

Immunohistochemical markers are the most helpful tool used to distinguish PCFCL from systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma involving the skin. Tumors of B-cell origin are expected to express associated B-cell markers such as CD20, CD79a, and PAX52; BCL-6, a marker of germinal center cells, also is expected to stain positive.2 CD10 is positive in a majority of cases with a follicular growth pattern, while those with a diffuse pattern of growth may have a negative stain.2 The most valuable histopathologic indicator differentiating primary and secondary skin involvement is the intensity of BCL-2 expression.5 The prognostic significance of the t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 rearrangement is controversial, with rearrangement identified in more than 75% of systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma cases and less commonly found in PCFCL, with one report arguing an incidence ranging from 1% to 40%.5

A comprehensive history and physical examination are necessary to develop a differential diagnosis. Our patient's lower leg edema and extensive medical history made the diagnosis more complicated. Pitting edema was present on physical examination, making elephantiasis nostras verrucosa less likely, as it would instead present with nonpitting edema and a woody feel.6 Our patient did not have epidemiologic exposure to filariasis through foreign travel and did not present with any classic signs or symptoms of lymphatic filariasis, such as fever, eosinophilia, chyluria, or hydrocele.7 Although a negative history of HIV makes Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis less likely diagnoses, a biopsy would be useful to rule out these conditions. Positive inguinal lymphadenopathy present on physical examination may have contributed to lymphatic flow obstruction leading to the leg lymphedema in our patient.

- Marsee DK, Pinkus GS, Yu H. CD71 (transferrin receptor): an effective marker for erythroid precursors in bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:429-435.

- Jaffe ES. Navigating the cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: avoiding the rocky shoals. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(suppl 1):96-106.

- Skala SL, Hristov B, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1313-1321.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Servitje O, Climent F, Colomo L, et al. Primary cutaneous vs secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas: a comparative study focused on BCL2, CD10, and t(14;18) expression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;46:182-189.

- Fredman R, Tenenhaus M. Elephantiasis nostras verrucose [published online October 12, 2012]. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic14.

- Lourens GB, Ferrell DK. Lymphatic filariasis. Nurs Clin of North Am. 2019;54:181-192.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology revealed a dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis with occasional individual cell necrosis. On closer inspection, the infiltrate consisted of intermediate-sized lymphocytes, some with a vesiculated nucleus and ample amount of cytoplasm, while others contained hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). These cells stained strongly positive for B-cell marker (CD20), while only a few mature lymphocytes demonstrated T-cell phenotype (CD3)(Figure 2).

Although the patient recounted a 3-month history of lower leg edema, he also reported that the rash began a few weeks after his diagnosis of systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma. Throughout this time, he was seen by various physicians who attributed the edema and skin changes to chronic stasis, peripheral venous insufficiency, and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. His primary care physician prescribed an antifungal lotion, which he discontinued on his own due to lack of improvement. Upon arrival to the emergency department, he was started on intravenous cefazolin and subcutaneous heparin. Doppler ultrasonography of the legs was ordered to rule out a deep venous thrombosis. Dermatology was consulted and proceeded with a punch biopsy to investigate for cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (BCL) with a plan to follow up as an outpatient for results upon discharge. He also was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for symptomatic relief.

The patient's left axillary lymph node was biopsied for pathologic evaluation. Immunohistochemical staining revealed expression of B-cell markers CD20, CD79a, and PAX5, along with the antiapoptotic markers BCL-2 and BCL-6. Fluorescence in situ hybridization displayed gene rearrangements of BCL-2, BCL-6, and t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 in the majority of cells. CD3 and CD5 immunostains were negative, indicating that T cells were not involved in this process. Flow cytometry identified a monoclonal κ B-cell population in 40% to 50% of the total cells, which co-expressed CD10, CD19, CD22, and CD38; the cells were negative for CD5, CD20, and CD23. Cell size was variably enlarged and CD71 positive, otherwise known as transferrin receptor 1, indicating the mediation of iron transport into cells of erythroid lineage that is necessary for proliferation.1 Bone marrow core biopsy did not identify features of bone marrow involvement by the lymphoma. Based on these results, the patient was diagnosed with systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma grade 3b stage IIIA. Oncology initiated a systemic chemotherapy regimen with obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine sulfate, and prednisone.

Skin involvement in B-cell follicular lymphoma can be primary or secondary. Although all subtypes of BCL can have secondary cutaneous involvement, it is most common in advanced-stage disease (stages III or IV).2 Cutaneous manifestations of primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma (PCFCL) and systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma secondarily involving the skin can be difficult to distinguish clinically and histopathologically; both appear as solitary or grouped plaques and nodules most commonly on the head, neck, or trunk, and rarely on the legs.3 Although the pathologic features of these two diagnoses can seem almost identical, it is important to differentiate them due to their differing prognosis and management. Patients with follicular lymphoma involving the skin are more likely than those with PCFCL to develop lymphadenopathy and B symptoms.3 Primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma also generally runs an indolent course and requires local therapy, while secondary involvement of the skin due to systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma has a worse prognosis and requires systemic chemotherapy treatment.4

Immunohistochemical markers are the most helpful tool used to distinguish PCFCL from systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma involving the skin. Tumors of B-cell origin are expected to express associated B-cell markers such as CD20, CD79a, and PAX52; BCL-6, a marker of germinal center cells, also is expected to stain positive.2 CD10 is positive in a majority of cases with a follicular growth pattern, while those with a diffuse pattern of growth may have a negative stain.2 The most valuable histopathologic indicator differentiating primary and secondary skin involvement is the intensity of BCL-2 expression.5 The prognostic significance of the t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 rearrangement is controversial, with rearrangement identified in more than 75% of systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma cases and less commonly found in PCFCL, with one report arguing an incidence ranging from 1% to 40%.5

A comprehensive history and physical examination are necessary to develop a differential diagnosis. Our patient's lower leg edema and extensive medical history made the diagnosis more complicated. Pitting edema was present on physical examination, making elephantiasis nostras verrucosa less likely, as it would instead present with nonpitting edema and a woody feel.6 Our patient did not have epidemiologic exposure to filariasis through foreign travel and did not present with any classic signs or symptoms of lymphatic filariasis, such as fever, eosinophilia, chyluria, or hydrocele.7 Although a negative history of HIV makes Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis less likely diagnoses, a biopsy would be useful to rule out these conditions. Positive inguinal lymphadenopathy present on physical examination may have contributed to lymphatic flow obstruction leading to the leg lymphedema in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology revealed a dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis with occasional individual cell necrosis. On closer inspection, the infiltrate consisted of intermediate-sized lymphocytes, some with a vesiculated nucleus and ample amount of cytoplasm, while others contained hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). These cells stained strongly positive for B-cell marker (CD20), while only a few mature lymphocytes demonstrated T-cell phenotype (CD3)(Figure 2).

Although the patient recounted a 3-month history of lower leg edema, he also reported that the rash began a few weeks after his diagnosis of systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma. Throughout this time, he was seen by various physicians who attributed the edema and skin changes to chronic stasis, peripheral venous insufficiency, and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. His primary care physician prescribed an antifungal lotion, which he discontinued on his own due to lack of improvement. Upon arrival to the emergency department, he was started on intravenous cefazolin and subcutaneous heparin. Doppler ultrasonography of the legs was ordered to rule out a deep venous thrombosis. Dermatology was consulted and proceeded with a punch biopsy to investigate for cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (BCL) with a plan to follow up as an outpatient for results upon discharge. He also was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for symptomatic relief.

The patient's left axillary lymph node was biopsied for pathologic evaluation. Immunohistochemical staining revealed expression of B-cell markers CD20, CD79a, and PAX5, along with the antiapoptotic markers BCL-2 and BCL-6. Fluorescence in situ hybridization displayed gene rearrangements of BCL-2, BCL-6, and t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 in the majority of cells. CD3 and CD5 immunostains were negative, indicating that T cells were not involved in this process. Flow cytometry identified a monoclonal κ B-cell population in 40% to 50% of the total cells, which co-expressed CD10, CD19, CD22, and CD38; the cells were negative for CD5, CD20, and CD23. Cell size was variably enlarged and CD71 positive, otherwise known as transferrin receptor 1, indicating the mediation of iron transport into cells of erythroid lineage that is necessary for proliferation.1 Bone marrow core biopsy did not identify features of bone marrow involvement by the lymphoma. Based on these results, the patient was diagnosed with systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma grade 3b stage IIIA. Oncology initiated a systemic chemotherapy regimen with obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine sulfate, and prednisone.

Skin involvement in B-cell follicular lymphoma can be primary or secondary. Although all subtypes of BCL can have secondary cutaneous involvement, it is most common in advanced-stage disease (stages III or IV).2 Cutaneous manifestations of primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma (PCFCL) and systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma secondarily involving the skin can be difficult to distinguish clinically and histopathologically; both appear as solitary or grouped plaques and nodules most commonly on the head, neck, or trunk, and rarely on the legs.3 Although the pathologic features of these two diagnoses can seem almost identical, it is important to differentiate them due to their differing prognosis and management. Patients with follicular lymphoma involving the skin are more likely than those with PCFCL to develop lymphadenopathy and B symptoms.3 Primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma also generally runs an indolent course and requires local therapy, while secondary involvement of the skin due to systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma has a worse prognosis and requires systemic chemotherapy treatment.4

Immunohistochemical markers are the most helpful tool used to distinguish PCFCL from systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma involving the skin. Tumors of B-cell origin are expected to express associated B-cell markers such as CD20, CD79a, and PAX52; BCL-6, a marker of germinal center cells, also is expected to stain positive.2 CD10 is positive in a majority of cases with a follicular growth pattern, while those with a diffuse pattern of growth may have a negative stain.2 The most valuable histopathologic indicator differentiating primary and secondary skin involvement is the intensity of BCL-2 expression.5 The prognostic significance of the t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 rearrangement is controversial, with rearrangement identified in more than 75% of systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma cases and less commonly found in PCFCL, with one report arguing an incidence ranging from 1% to 40%.5

A comprehensive history and physical examination are necessary to develop a differential diagnosis. Our patient's lower leg edema and extensive medical history made the diagnosis more complicated. Pitting edema was present on physical examination, making elephantiasis nostras verrucosa less likely, as it would instead present with nonpitting edema and a woody feel.6 Our patient did not have epidemiologic exposure to filariasis through foreign travel and did not present with any classic signs or symptoms of lymphatic filariasis, such as fever, eosinophilia, chyluria, or hydrocele.7 Although a negative history of HIV makes Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis less likely diagnoses, a biopsy would be useful to rule out these conditions. Positive inguinal lymphadenopathy present on physical examination may have contributed to lymphatic flow obstruction leading to the leg lymphedema in our patient.

- Marsee DK, Pinkus GS, Yu H. CD71 (transferrin receptor): an effective marker for erythroid precursors in bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:429-435.

- Jaffe ES. Navigating the cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: avoiding the rocky shoals. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(suppl 1):96-106.

- Skala SL, Hristov B, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1313-1321.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Servitje O, Climent F, Colomo L, et al. Primary cutaneous vs secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas: a comparative study focused on BCL2, CD10, and t(14;18) expression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;46:182-189.

- Fredman R, Tenenhaus M. Elephantiasis nostras verrucose [published online October 12, 2012]. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic14.

- Lourens GB, Ferrell DK. Lymphatic filariasis. Nurs Clin of North Am. 2019;54:181-192.

- Marsee DK, Pinkus GS, Yu H. CD71 (transferrin receptor): an effective marker for erythroid precursors in bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:429-435.

- Jaffe ES. Navigating the cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: avoiding the rocky shoals. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(suppl 1):96-106.

- Skala SL, Hristov B, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1313-1321.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Servitje O, Climent F, Colomo L, et al. Primary cutaneous vs secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas: a comparative study focused on BCL2, CD10, and t(14;18) expression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;46:182-189.

- Fredman R, Tenenhaus M. Elephantiasis nostras verrucose [published online October 12, 2012]. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic14.

- Lourens GB, Ferrell DK. Lymphatic filariasis. Nurs Clin of North Am. 2019;54:181-192.

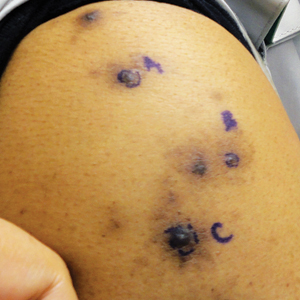

A 60-year-old man presented to the emergency department with slowly progressing edema of the lower legs of 3 months’ duration. In the week prior to presentation to the emergency department, he noticed a sudden eruption of vesicles and bullae on the right leg that drained clear fluid and healed with brown crust. The lesions were associated with mild burning, pruritus, and pain. He denied fever, chills, recent travel, or injury. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, hyperlipidemia, and chronic anemia. Physical examination revealed multiple scattered erythematous vesicles and bullae on the right leg on a background of hyperpigmentation. Bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the legs also was present. A punch biopsy of a lesion was performed.

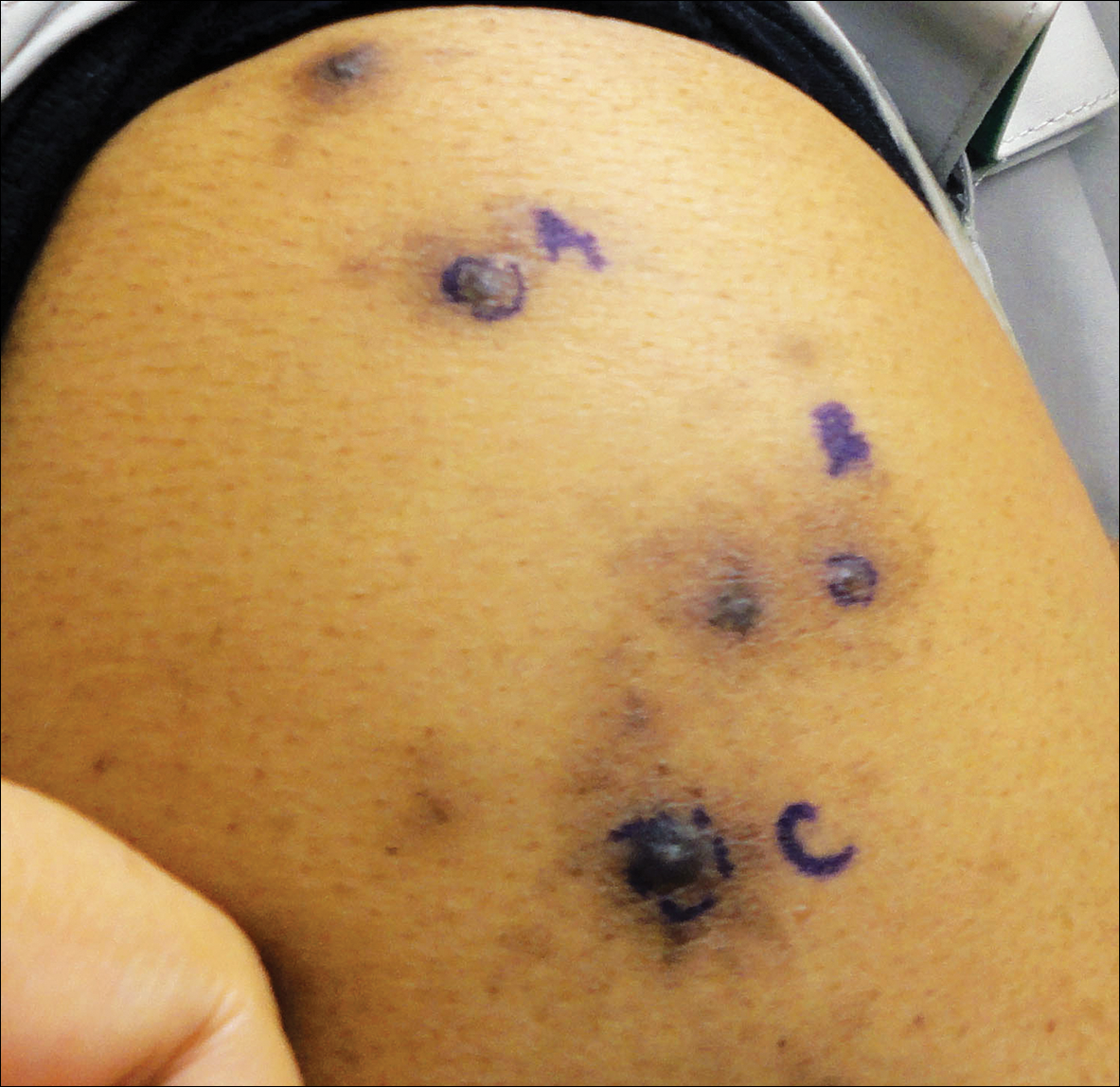

Brown-Black Papulonodules on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.

- Spoerke DG, Spoerke SE. Granuloma formation induced by spines of the cactus, Opuntia acanthocarpa. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:342-344.

- Madkan VK, Abraham T, Lesher JL Jr. Cactus spine granuloma. Cutis. 2007;79:208-210.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- McGovern TW, Barkley TM. Botanical dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:321-334.

- Lindsey D, Lindsey WE. Cactus spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:362-369.

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5

Regarding treatment of chronic granulomas, Madkan et al4 reported a case that showed some improvement with clobetasol ointment; however, clinical lesions resolved only after punch biopsies were performed to confirm the diagnosis of cactus spine granuloma. In a controlled study in rabbits, glochids were successfully removed by first detaching the larger clumps with tweezers then applying glue and gauze to the affected area.6 After the glue dried, the gauze was peeled off, resulting in the removal of 95% of the implanted glochids. Overall, removal of embedded spines is difficult because the glochids typically radiate in several directions.7 Treatment of foreign body granulomas caused by cactus spines can be achieved by expulsion of plant matter remnants and symptomatic treatment using midpotency topical steroids twice daily.4 Uncovering and performing punch biopsies of papules also can result in rapid healing of the lesions. Without manual removal of the glochid, lesions can persist for 2 to 8 months until gradual resolution with possible postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.4

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.

- Spoerke DG, Spoerke SE. Granuloma formation induced by spines of the cactus, Opuntia acanthocarpa. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:342-344.

- Madkan VK, Abraham T, Lesher JL Jr. Cactus spine granuloma. Cutis. 2007;79:208-210.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- McGovern TW, Barkley TM. Botanical dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:321-334.

- Lindsey D, Lindsey WE. Cactus spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:362-369.

- Suzuki H, Baba S. Cactus granuloma of the skin. J Dermatol. 1993;20:424-427.

- Suárez A, Freeman S, Puls L, et al. Unusual presentation of cactus spines in the flank of an elderly man: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:152.

- Spoerke DG, Spoerke SE. Granuloma formation induced by spines of the cactus, Opuntia acanthocarpa. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:342-344.

- Madkan VK, Abraham T, Lesher JL Jr. Cactus spine granuloma. Cutis. 2007;79:208-210.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- McGovern TW, Barkley TM. Botanical dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:321-334.

- Lindsey D, Lindsey WE. Cactus spine injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:362-369.

A 63-year-old man presented with a pruritic rash on the right arm of approximately 3 months' duration. On physical examination, several discrete, 4- to 5-mm, brown-black papulonodules with a central punctum were identified along the extensor aspects of the upper and lower right arm. No foreign bodies were appreciated. Biopsies of nodules on the right upper arm were performed (sites marked with letters).