User login

Pediatric Observation Status Stays

In recent decades, hospital lengths of stay have decreased and there has been a shift toward outpatient management for many pediatric conditions. In 2003, one‐third of all children admitted to US hospitals experienced 1‐day inpatient stays, an increase from 19% in 1993.1 Some hospitals have developed dedicated observation units for the care of children, with select diagnoses, who are expected to respond to less than 24 hours of treatment.26 Expansion of observation services has been suggested as an approach to lessen emergency department (ED) crowding7 and alleviate high‐capacity conditions within hospital inpatient units.8

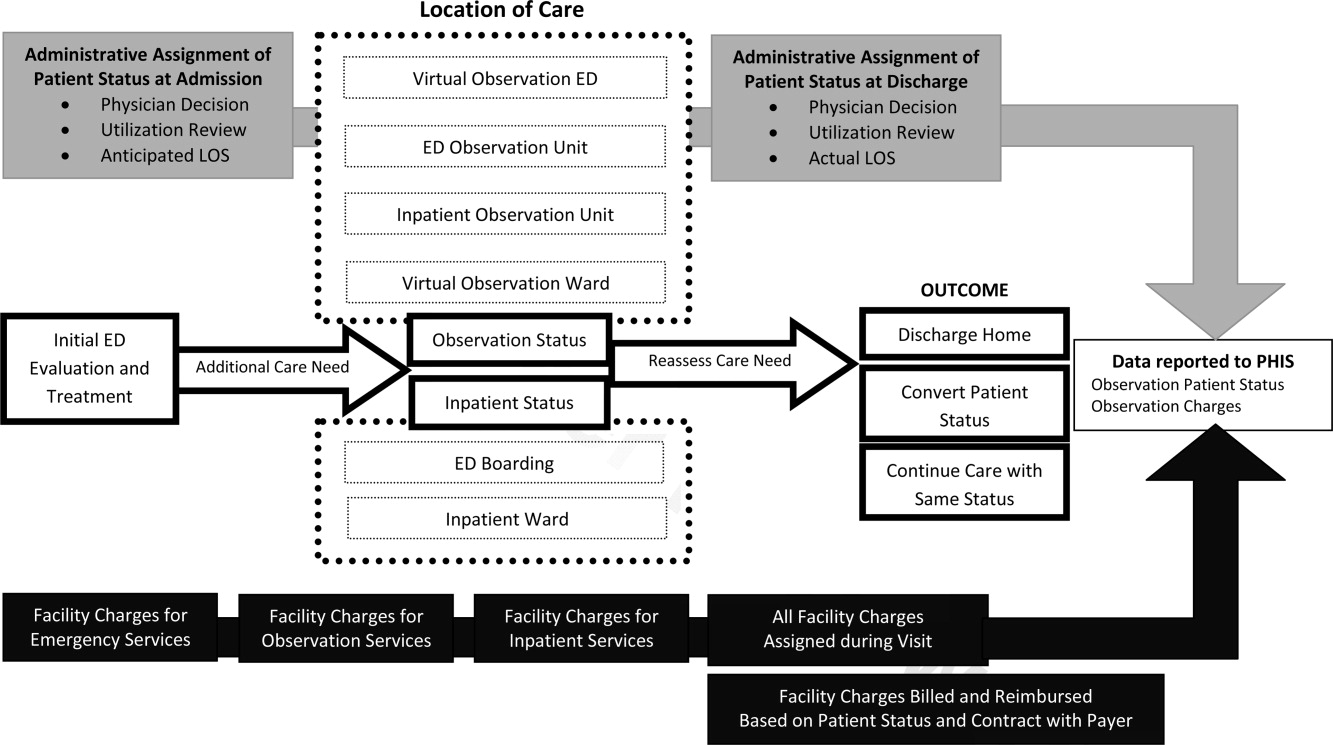

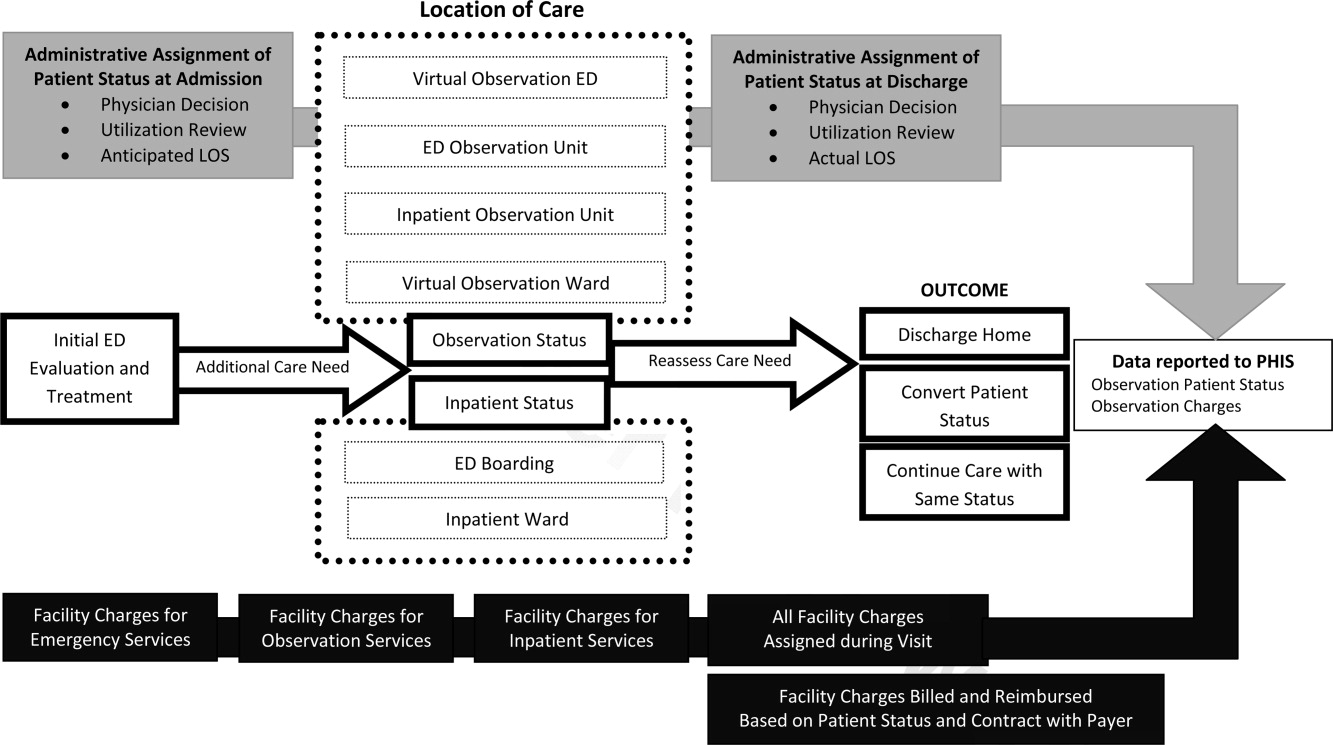

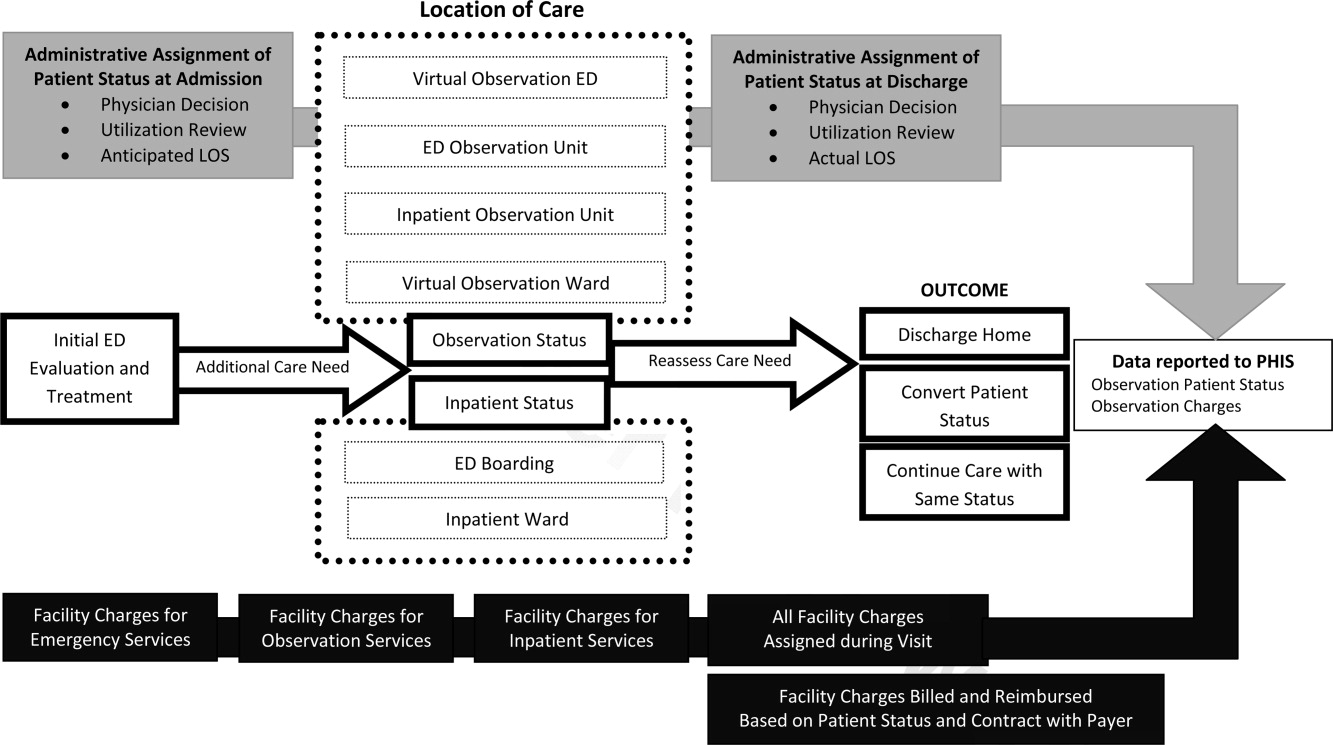

In contrast to care delivered in a dedicated observation unit, observation status is an administrative label applied to patients who do not meet inpatient criteria as defined by third parties such as InterQual. While the decision to admit a patient is ultimately at the discretion of the ordering physician, many hospitals use predetermined criteria to assign observation status to patients admitted to observation and inpatient units.9 Treatment provided under observation status is designated by hospitals and payers as outpatient care, even when delivered in an inpatient bed.10 As outpatient‐designated care, observation cases do not enter publicly available administrative datasets of hospital discharges that have traditionally been used to understand hospital resource utilization, including the National Hospital Discharge Survey and the Kid's Inpatient Database.11, 12

We hypothesize that there has been an increase in observation status care delivered to children in recent years, and that the majority of children under observation were discharged home without converting to inpatient status. To determine trends in pediatric observation status care, we conducted the first longitudinal, multicenter evaluation of observation status code utilization following ED treatment in a sample of US freestanding children's hospitals. In addition, we focused on the most recent year of data among top ranking diagnoses to assess the current state of observation status stay outcomes (including conversion to inpatient status and return visits).

METHODS

Data Source

Data for this multicenter retrospective cohort study were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). Freestanding children's hospital's participating in PHIS account for approximately 20% of all US tertiary care children's hospitals. The PHIS hospitals provide resource utilization data including patient demographics, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) diagnosis and procedure codes, and charges applied to each stay, including room and nursing charges. Data were de‐identified prior to inclusion in the database, however encrypted identification numbers allowed for tracking individual patients across admissions. Data quality and reliability were assured through a joint effort between the Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA; Shawnee Mission, KS) and participating hospitals as described previously.13, 14 In accordance with the Common Rule (45 CFR 46.102(f)) and the policies of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board, this research, using a de‐identified dataset, was considered exempt from review.

Hospital Selection

Each year from 2004 to 2009, there were 18 hospitals participating in PHIS that reported data from both inpatient discharges and outpatient visits (including observation status discharges). To assess data quality for observation status stays, we evaluated observation status discharges for the presence of associated observation billing codes applied to charge records reported to PHIS including: 1) observation per hour, 2) ED observation time, or 3) other codes mentioning observation in the hospital charge master description document. The 16 hospitals with observation charges assigned to at least 90% of observation status discharges in each study year were selected for analysis.

Visit Identification

Within the 16 study hospitals, we identified all visits between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 with ED facility charges. From these ED visits, we included any stays designated by the hospital as observation or inpatient status, excluding transfers and ED discharges.

Variable Definitions

Hospitals submitting records to PHIS assigned a single patient type to the episode of care. The Observation patient type was assigned to patients discharged from observation status. Although the duration of observation is often less than 24 hours, hospitals may allow a patient to remain under observation for longer durations.15, 16 Duration of stay is not defined precisely enough within PHIS to determine hours of inpatient care. Therefore, length of stay (LOS) was not used to determine observation status stays.

The Inpatient patient type was assigned to patients who were discharged from inpatient status, including those patients admitted to inpatient care from the ED and also those who converted to inpatient status from observation. Patients who converted from observation status to inpatient status during the episode of care could be identified through the presence of observation charge codes as described above.

Given the potential for differences in the application of observation status, we also identified 1‐Day Stays where discharge occurred on the day of, or the day following, an inpatient status admission. These 1‐Day Stays represent hospitalizations that may, by their duration, be suitable for care in an observation unit. We considered discharges in the Observation and 1‐Day Stay categories to be Short‐Stays.

DATA ANALYSIS

For each of the 6 years of study, we calculated the following proportions to determine trends over time: 1) the number of Observation Status admissions from the ED as a proportion of the total number of ED visits resulting in Observation or Inpatient admission, and 2) the number of 1‐Day Stays admitted from the ED as a proportion of the total number of ED visits resulting in Observation or Inpatient admissions. Trends were analyzed using linear regression. Trends were also calculated for the total volume of admissions from the ED and the case‐mix index (CMI). CMI was assessed to evaluate for changes in the severity of illness for children admitted from the ED over the study period. Each hospital's CMI was calculated as an average of their Observation and Inpatient Status discharges' charge weights during the study period. Charge weights were calculated at the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR‐DRG)/severity of illness level (3M Health Information Systems, St Paul, MN) and were normalized national average charges derived by Thomson‐Reuters from their Pediatric Projected National Database. Weights were then assigned to each discharge based on the discharge's APR‐DRG and severity level assignment.

To assess the current outcomes for observation, we analyzed stays with associated observation billing codes from the most recent year of available data (2009). Stays with Observation patient type were considered to have been discharged from observation, while those with an Inpatient Status patient type were considered to have converted to an inpatient admission during the observation period.

Using the 2009 data, we calculated descriptive statistics for patient characteristics (eg, age, gender, payer) comparing Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions using chi‐square statistics. Age was categorized using the American Academy of Pediatrics groupings: <30 days, 30 days1 year, 12 years, 34 years, 512 years, 1317 years, >18 years. Designated payer was categorized into government, private, and other, including self‐pay and uninsured groups.

We used the Severity Classification Systems (SCS) developed for pediatric emergency care to estimate severity of illness for the visit.17 In this 5‐level system, each ICD‐9 diagnosis code is associated with a score related to the intensity of ED resources needed to care for a child with that diagnosis. In our analyses, each case was assigned the maximal SCS category based on the highest severity ICD‐9 code associated with the stay. Within the SCS, a score of 1 indicates minor illness (eg, diaper dermatitis) and 5 indicates major illness (eg, septic shock). The proportions of visits within categorical SCS scores were compared for Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions using chi‐square statistics.

We determined the top 10 ranking diagnoses for which children were admitted from the ED in 2009 using the Diagnosis Grouping System (DGS).18 The DGS was designed specifically to categorize pediatric ED visits into clinically meaningful groups. The ICD‐9 code for the principal discharge diagnosis was used to assign records to 1 of the 77 DGS subgroups. Within each of the top ranking DGS subgroups, we determined the proportion of Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions.

To provide clinically relevant outcomes of Observation Stays for common conditions, we selected stays with observation charges from within the top 10 ranking observation stay DGS subgroups in 2009. Outcomes for observation included: 1) immediate outcome of the observation stay (ie, discharge or conversion to inpatient status), 2) return visits to the ED in the 3 days following observation, and 3) readmissions to the hospital in the 3 and 30 days following observation. Bivariate comparisons of return visits and readmissions for Observation versus 1‐Day Stays within DGS subgroups were analyzed using chi‐square tests. Multivariate analyses of return visits and readmissions were conducted using Generalized Estimating Equations adjusting for severity of illness by SCS score and clustering by hospital. To account for local practice patterns, we also adjusted for a grouped treatment variable that included the site level proportion of children admitted to Observation Status, 1‐Day‐Stays, and longer Inpatient admissions. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC); P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Trends in Short‐Stays

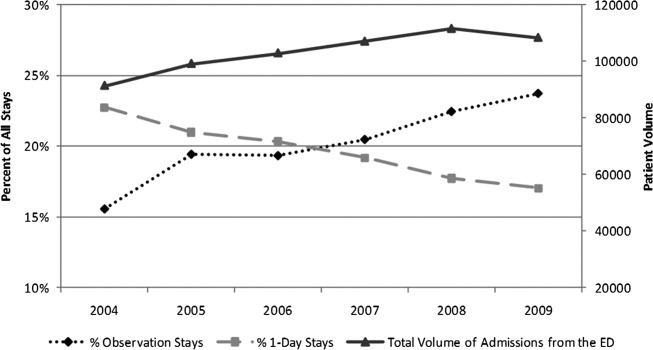

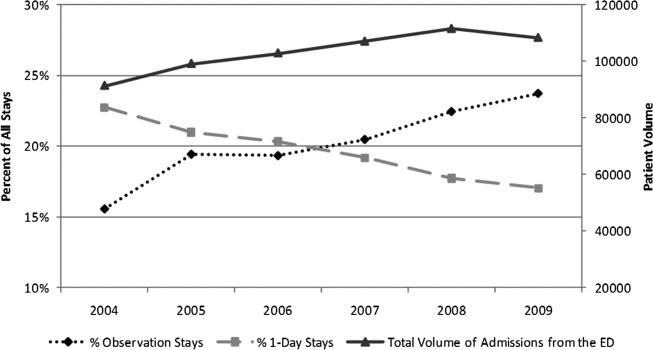

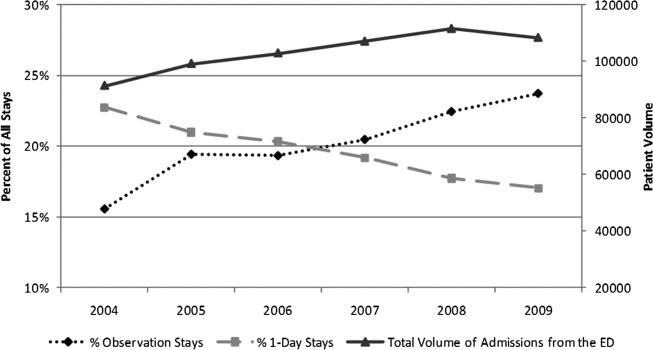

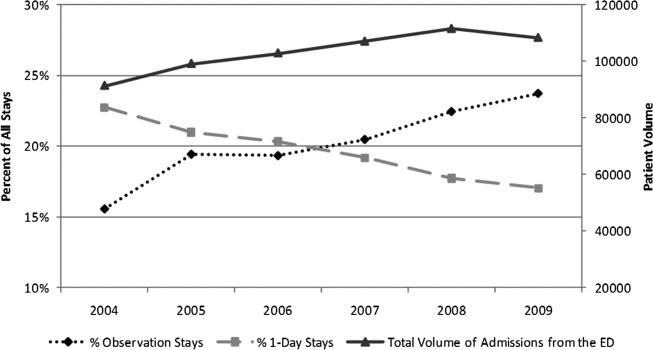

An increase in proportion of Observation Stays was mirrored by a decrease in proportion of 1‐Day Stays over the study period (Figure 1). In 2009, there were 1.4 times more Observation Stays than 1‐Day Stays (25,653 vs 18,425) compared with 14,242 and 20,747, respectively, in 2004. This shift toward more Observation Stays occurred as hospitals faced a 16% increase in the total number of admissions from the ED (91,318 to 108,217) and change in CMI from 1.48 to 1.51. Over the study period, roughly 40% of all admissions from the ED were Short‐Stays (Observation and 1‐Day Stays). Median LOS for Observation Status stays was 1 day (interquartile range [IQR]: 11).

Patient Characteristics in 2009

Table 1 presents comparisons between Observation, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions. Of potential clinical significance, children under Observation Status were slightly younger (median, 4.0 years; IQR: 1.310.0) when compared with children admitted for 1‐Day Stays (median, 5.0 years; IQR: 1.411.4; P < 0.001) and longer‐duration Inpatient stays (median, 4.7 years; IQR: 0.912.2; P < 0.001). Nearly two‐thirds of Observation Status stays had SCS scores of 3 or lower compared with less than half of 1‐Day Stays and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions.

| Short‐Stays | LOS >1 Day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | 1‐Day Stay | Longer Admission | ||||

| N = 25,653* (24%) | N = 18,425* (17%) | P Value Comparing Observation to 1‐Day Stay | N = 64,139* (59%) | P Value Comparing Short‐Stays to LOS >1 Day | ||

| ||||||

| Sex | Male | 14,586 (57) | 10,474 (57) | P = 0.663 | 34,696 (54) | P < 0.001 |

| Female | 11,000 (43) | 7,940 (43) | 29,403 (46) | |||

| Payer | Government | 13,247 (58) | 8,944 (55) | P < 0.001 | 35,475 (61) | P < 0.001 |

| Private | 7,123 (31) | 5,105 (32) | 16,507 (28) | |||

| Other | 2,443 (11) | 2,087 (13) | 6,157 (11) | |||

| Age | <30 days | 793 (3) | 687 (4) | P < 0.001 | 3,932 (6) | P < 0.001 |

| 30 days1 yr | 4,499 (17) | 2,930 (16) | 13,139 (21) | |||

| 12 yr | 5,793 (23) | 3,566 (19) | 10,229 (16) | |||

| 34 yr | 3,040 (12) | 2,056 (11) | 5,551 (9) | |||

| 512 yr | 7,427 (29) | 5,570 (30) | 17,057 (27) | |||

| 1317 yr | 3,560 (14) | 3,136 (17) | 11,860 (18) | |||

| >17 yr | 541 (2) | 480 (3) | 2,371 (4) | |||

| Race | White | 17,249 (70) | 12,123 (70) | P < 0.001 | 40,779 (67) | P <0.001 |

| Black | 6,298 (25) | 4,216 (25) | 16,855 (28) | |||

| Asian | 277 (1) | 295 (2) | 995 (2) | |||

| Other | 885 (4) | 589 (3) | 2,011 (3) | |||

| SCS | 1 Minor illness | 64 (<1) | 37 (<1) | P < 0.001 | 84 (<1) | P < 0.001 |

| 2 | 1,190 (5) | 658 (4) | 1,461 (2) | |||

| 3 | 14,553 (57) | 7,617 (42) | 20,760 (33) | |||

| 4 | 8,994 (36) | 9,317 (51) | 35,632 (56) | |||

| 5 Major illness | 490 (2) | 579 (3) | 5,689 (9) | |||

In 2009, the top 10 DGS subgroups accounted for half of all admissions from the ED. The majority of admissions for extremity fractures, head trauma, dehydration, and asthma were Short‐Stays, as were roughly 50% of admissions for seizures, appendicitis, and gastroenteritis (Table 2). Respiratory infections and asthma were the top 1 and 2 ranking DGS subgroups for Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions. While rank order differed, 9 of the 10 top ranking Observation Stay DGS subgroups were also top ranking DGS subgroups for 1‐Day Stays. Gastroenteritis ranked 10th among Observation Stays and 11th among 1‐Day Stays. Diabetes mellitus ranked 26th among Observation Stays compared with 8th among 1‐Day Stays.

| Short‐Stays | LOS >1 Day | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % Observation | % 1‐Day Stay | % Longer Admission | |

| |||

| All admissions from the ED | 23.7 | 17.0 | 59.3 |

| n = 108,217 | |||

| Respiratory infections | 22.3 | 15.3 | 62.4 |

| n = 14,455 (13%) | |||

| Asthma | 32.0 | 23.8 | 44.2 |

| n = 8,853 (8%) | |||

| Other GI diseases | 24.1 | 16.2 | 59.7 |

| n = 6,519 (6%) | |||

| Appendicitis | 21.0 | 29.5 | 49.5 |

| n = 4,480 (4%) | |||

| Skin infections | 20.7 | 14.3 | 65.0 |

| n = 4,743 (4%) | |||

| Seizures | 29.5 | 22 | 48.5 |

| n = 4,088 (4%) | |||

| Extremity fractures | 49.4 | 20.5 | 30.1 |

| n = 3,681 (3%) | |||

| Dehydration | 37.8 | 19.0 | 43.2 |

| n = 2,773 (3%) | |||

| Gastroenteritis | 30.3 | 18.7 | 50.9 |

| n = 2,603 (2%) | |||

| Head trauma | 44.1 | 43.9 | 32.0 |

| n = 2,153 (2%) | |||

Average maximum SCS scores were clinically comparable for Observation and 1‐Day Stays and generally lower than for longer‐duration Inpatient admissions within the top 10 most common DGS subgroups. Average maximum SCS scores were statistically lower for Observation Stays compared with 1‐Day Stays for respiratory infections (3.2 vs 3.4), asthma (3.4 vs 3.6), diabetes (3.5 vs 3.8), gastroenteritis (3.0 vs 3.1), other gastrointestinal diseases (3.2 vs 3.4), head trauma (3.3 vs 3.5), and extremity fractures (3.2 vs 3.4) (P < 0.01). There were no differences in SCS scores for skin infections (SCS = 3.0) and appendicitis (SCS = 4.0) when comparing Observation and 1‐Day Stays.

Outcomes for Observation Stays in 2009

Within 6 of the top 10 DGS subgroups for Observation Stays, >75% of patients were discharged home from Observation Status (Table 3). Mean LOS for stays that converted from Observation to Inpatient Status ranged from 2.85 days for extremity fractures to 4.66 days for appendicitis.

| Return to ED in 3 Days n = 421 (1.6%) | Hospital Readmissions in 3 Days n = 247 (1.0%) | Hospital Readmissions in 30 Days n = 819 (3.2%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGS subgroup | % Discharged From Observation | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| ||||

| Respiratory infections | 72 | 1.1 (0.71.8) | 0.8 (0.51.3) | 0.9 (0.71.3) |

| Asthma | 80 | 1.3 (0.63.0) | 1.0 (0.61.8) | 0.5 (0.31.0) |

| Other GI diseases | 74 | 0.8 (0.51.3) | 2.2 (1.33.8) | 1.0 (0.71.5) |

| Appendicitis | 82 | NE | NE | NE |

| Skin infections | 68 | 1.8 (0.84.4) | 1.4 (0.45.3) | 0.9 (0.61.6) |

| Seizures | 79 | 0.8 (0.41.6) | 0.8 (0.31.8) | 0.7 (0.51.0) |

| Extremity fractures | 92 | 0.9 (0.42.1) | 0.2 (01.3) | 1.2 (0.53.2) |

| Dehydration | 81 | 0.9 (0.61.4) | 0.8 (0.31.9) | 0.7 (0.41.1) |

| Gastroenteritis | 74 | 0.9 (0.42.0) | 0.6 (0.41.2) | 0.6 (0.41) |

| Head trauma | 92 | 0.6 (0.21.7) | 0.3 (02.1) | 1.0 (0.42.8) |

Among children with Observation Stays for 1 of the top 10 DGS subgroups, adjusted return ED visit rates were <3% and readmission rates were <1.6% within 3 days following the index stay. Thirty‐day readmission rates were highest following observation for other GI illnesses and seizures. In unadjusted analysis, Observation Stays for asthma, respiratory infections, and skin infections were associated with greater proportions of return ED visits when compared with 1‐Day Stays. Differences were no longer statistically significant after adjusting for SCS score, clustering by hospital, and the grouped treatment variable. Adjusted odds of readmission were significantly higher at 3 days following observation for other GI illnesses and lower at 30 days following observation for seizures when compared with 1‐Day Stays (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this first, multicenter longitudinal study of pediatric observation following an ED visit, we found that Observation Status code utilization has increased steadily over the past 6 years and, in 2007, the proportion of children admitted to observation status surpassed the proportion of children experiencing a 1‐day inpatient admission. Taken together, Short‐Stays made up more than 40% of the hospital‐based care delivered to children admitted from an ED. Stable trends in CMI over time suggest that observation status may be replacing inpatient status designated care for pediatric Short‐Stays in these hospitals. Our findings suggest the lines between outpatient observation and short‐stay inpatient care are becoming increasingly blurred. These trends have occurred in the setting of changing policies for hospital reimbursement, requirements for patients to meet criteria to qualify for inpatient admissions, and efforts to avoid stays deemed unnecessary or inappropriate by their brief duration.19 Therefore there is a growing need to understand the impact of children under observation on the structure, delivery, and financing of acute hospital care for children.

Our results also have implications for pediatric health services research that relies on hospital administrative databases that do not contain observation stays. Currently, observation stays are systematically excluded from many inpatient administrative datasets.11, 12 Analyses of datasets that do not account for observation stays likely result in underestimation of hospitalization rates and hospital resource utilization for children. This may be particularly important for high‐volume conditions, such as asthma and acute infections, for which children commonly require brief periods of hospital‐based care beyond an ED encounter. Data from pediatric observation status admissions should be consistently included in hospital administrative datasets to allow for more comprehensive analyses of hospital resource utilization among children.

Prior research has shown that the diagnoses commonly treated in pediatric observation units overlap with the diagnoses for which children experience 1‐Day Stays.1, 20 We found a similar pattern of conditions for which children were under Observation Status and 1‐Day Stays with comparable severity of illness between the groups in terms of SCS scores. Our findings imply a need to determine how and why hospitals differentiate Observation Status from 1‐Day‐Stay groups in order to improve the assignment of observation status. Assuming continued pressures from payers to provide more care in outpatient or observation settings, there is potential for expansion of dedicated observation services for children in the US. Without designated observation units or processes to group patients with lower severity conditions, there may be limited opportunities to realize more efficient hospital care simply through the application of the label of observation status.

For more than 30 years, observation services have been provided to children who require a period of monitoring to determine their response to therapy and the need for acute inpatient admission from the ED.21While we were not able to determine the location of care for observation status patients in this study, we know that few children's hospitals have dedicated observation units and, even when an observation unit is present, not all observation status patients are cared for in dedicated observation units.9 This, in essence, means that most children under observation status are cared for in virtual observation by inpatient teams using inpatient beds. If observation patients are treated in inpatient beds and consume the same resources as inpatients, then cost‐savings based on reimbursement contracts with payers may not reflect an actual reduction in services. Pediatric institutions will need to closely monitor the financial implications of observation status given the historical differences in payment for observation and inpatient care.

With more than 70% of children being discharged home following observation, our results are comparable to the published literature2, 5, 6, 22, 23 and guidelines for observation unit operations.24 Similar to prior studies,4, 15, 2530 our results also indicate that return visits and readmissions following observation are uncommon events. Our findings can serve as initial benchmarks for condition‐specific outcomes for pediatric observation care. Studies are needed both to identify the clinical characteristics predictive of successful discharge home from observation and to explore the hospital‐to‐hospital variability in outcomes for observation. Such studies are necessary to identify the most successful healthcare delivery models for pediatric observation stays.

LIMITATIONS

The primary limitation to our results is that data from a subset of freestanding children's hospitals may not reflect observation stays at other children's hospitals or the community hospitals that care for children across the US. Only 18 of 42 current PHIS member hospitals have provided both outpatient visit and inpatient stay data for each year of the study period and were considered eligible. In an effort to ensure the quality of observation stay data, we included the 16 hospitals that assigned observation charges to at least 90% of their observation status stays in the PHIS database. The exclusion of the 2 hospitals where <90% of observation status patients were assigned observation charges likely resulted in an underestimation of the utilization of observation status.

Second, there is potential for misclassification of patient type given institutional variations in the assignment of patient status. The PHIS database does not contain information about the factors that were considered in the assignment of observation status. At the time of admission from the ED, observation or inpatient status is assigned. While this decision is clearly reserved for the admitting physician, the process is not standardized across hospitals.9 Some institutions have Utilization Managers on site to help guide decision‐making, while others allow the assignment to be made by physicians without specific guidance. As a result, some patients may be assigned to observation status at admission and reassigned to inpatient status following Utilization Review, which may bias our results toward overestimation of the number of observation stays that converted to inpatient status.

The third limitation to our results relates to return visits. An accurate assessment of return visits is subject to the patient returning to the same hospital. If children do not return to the same hospital, our results would underestimate return visits and readmissions. In addition, we did not assess the reason for return visit as there was no way to verify if the return visit was truly related to the index visit without detailed chart review. Assuming children return to the same hospital for different reasons, our results would overestimate return visits associated with observation stays. We suspect that many 3‐day return visits result from the progression of acute illness or failure to respond to initial treatment, and 30‐day readmissions reflect recurrent hospital care needs related to chronic illnesses.

Lastly, severity classification is difficult when analyzing administrative datasets without physiologic patient data, and the SCS may not provide enough detail to reveal clinically important differences between patient groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Short‐stay hospitalizations following ED visits are common among children, and the majority of pediatric short‐stays are under observation status. Analyses of inpatient administrative databases that exclude observation stays likely result in an underestimation of hospital resource utilization for children. Efforts are needed to ensure that patients under observation status are accounted for in hospital administrative datasets used for pediatric health services research, and healthcare resource allocation, as it relates to hospital‐based care. While the clinical outcomes for observation patients appear favorable in terms of conversion to inpatient admissions and return visits, the financial implications of observation status care within children's hospitals are currently unknown.

- ,,,,,.Trends in high‐turnover stays among children hospitalized in the United States, 1993–2003.Pediatrics.2009;123(3):996–1002.

- ,,,,.Utilization and unexpected hospitalization rates of a pediatric emergency department 23‐hour observation unit.Pediatr Emerg Care.2008;24(9):589–594.

- ,,.When the patient requires observation not hospitalization.J Nurs Admin.1988;18(10):20–23.

- ,,,.Pediatric observation status beds on an inpatient unit: an integrated care model.Pediatr Emerg Care.2004;20(1):17–21.

- ,,.Use of an observation unit by a pediatric emergency department for common pediatric illnesses.Pediatr Emerg Care.2001;17(5):321–323.

- ,,.The pediatric hybrid observation unit: an analysis of 6477 consecutive patient encounters.Pediatrics.2005;115(5):e535–e542.

- ACEP. Emergency Department Crowding: High‐Impact Solutions. Task Force Report on Boarding.2008. Available at: http://www.acep.org/WorkArea/downloadasset.aspx?id=37960. Accessed July 21, 2010.

- ,,, et al.Children's hospitals do not acutely respond to high occupancy.Pediatrics.2010;125(5):974–981.

- ,,, et al.Differences in observation care practices in US freestanding children's hospitals: are they virtual or real?J Hosp Med.2011. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/transmittals/downloads/R770HO.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2011.

- CMS.Medicare Hospital Manual, Section 455.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services;2001. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/FinalReportonObservationStatus_v2Final.pdf. Accessed on May 3, 2007.

- HCUP.Methods Series Report #2002–3. Observation Status Related to U.S. Hospital Records. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2002.

- ,.Design and operation of the National Hospital Discharge Survey: 1988 redesign.Vital Health Stat.2000;1(39):1–43.

- ,,,.Corticosteroids and mortality in children with bacterial meningitis.JAMA.2008;299(17):2048–2055.

- ,,,,.Intravenous immunoglobulin in children with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.Clin Infect Dis.2009;49(9):1369–1376.

- ,,,.Impact of a short stay unit on asthma patients admitted to a tertiary pediatric hospital.Qual Manag Health Care.1997;6(1):14–22.

- ,,.An observation unit in a pediatric emergency department: one children's hospital's experience.J Emerg Nurs.2002;28(5):407–413.

- ,,,.Developing a diagnosis‐based severity classification system for use in emergency medical systems for children. Pediatric Academic Societies' Annual Meeting, Platform Presentation; Toronto, Canada;2007.

- ,,,,.A new diagnosis grouping system for child emergency department visits.Acad Emerg Med.2010;17(2):204–213.

- .Observation medicine: the healthcare system's tincture of time. In: Graff LG, ed.Principles of Observation Medicine.American College of Emergency Physicians;2010. Available at: http://www. acep.org/content.aspx?id=46142. Accessed February 18, 2011.

- ,,,,.High turnover stays for pediatric asthma in the United States: analysis of the 2006 Kids' Inpatient Database.Med Care.2010;48(9):827–833.

- ,,,,.Pediatric observation units in the United States: a systematic review.J Hosp Med.2010;5(3):172–182.

- ,.Observation unit in childrens hospital—adjunct to delivery and teaching of ambulatory pediatric care.N Y State J Med.1980;80(11):1684–1686.

- ,,.Short stay in an outpatient department. An alternative to hospitalization.Am J Dis Child.1972;123(2):128–132.

- ACEP.Practice Management Committee, American College of Emergency Physicians. Management of Observation Units.Irving, TX:American College of Emergency Physicians;1994.

- ,,,,.Return visits to a pediatric emergency department.Pediatr Emerg Care.2004;20(3):166–171.

- ,.Postreduction management of intussusception in a children's hospital emergency department.Pediatrics.2003;112(6 pt 1):1302–1307.

- ,,,,.Pediatric closed head injuries treated in an observation unit.Pediatr Emerg Care.2005;21(10):639–644.

- ,,,.Use of pediatric observation unit for treatment of children with dehydration caused by gastroenteritis.Pediatr Emerg Care.2006;22(1):1–6.

- ,,,.Children with asthma admitted to a pediatric observation unit.Pediatr Emerg Care.2005;21(10):645–649.

- ,,, et al.How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study.Pediatrics.2009;123(1):286–293.

In recent decades, hospital lengths of stay have decreased and there has been a shift toward outpatient management for many pediatric conditions. In 2003, one‐third of all children admitted to US hospitals experienced 1‐day inpatient stays, an increase from 19% in 1993.1 Some hospitals have developed dedicated observation units for the care of children, with select diagnoses, who are expected to respond to less than 24 hours of treatment.26 Expansion of observation services has been suggested as an approach to lessen emergency department (ED) crowding7 and alleviate high‐capacity conditions within hospital inpatient units.8

In contrast to care delivered in a dedicated observation unit, observation status is an administrative label applied to patients who do not meet inpatient criteria as defined by third parties such as InterQual. While the decision to admit a patient is ultimately at the discretion of the ordering physician, many hospitals use predetermined criteria to assign observation status to patients admitted to observation and inpatient units.9 Treatment provided under observation status is designated by hospitals and payers as outpatient care, even when delivered in an inpatient bed.10 As outpatient‐designated care, observation cases do not enter publicly available administrative datasets of hospital discharges that have traditionally been used to understand hospital resource utilization, including the National Hospital Discharge Survey and the Kid's Inpatient Database.11, 12

We hypothesize that there has been an increase in observation status care delivered to children in recent years, and that the majority of children under observation were discharged home without converting to inpatient status. To determine trends in pediatric observation status care, we conducted the first longitudinal, multicenter evaluation of observation status code utilization following ED treatment in a sample of US freestanding children's hospitals. In addition, we focused on the most recent year of data among top ranking diagnoses to assess the current state of observation status stay outcomes (including conversion to inpatient status and return visits).

METHODS

Data Source

Data for this multicenter retrospective cohort study were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). Freestanding children's hospital's participating in PHIS account for approximately 20% of all US tertiary care children's hospitals. The PHIS hospitals provide resource utilization data including patient demographics, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) diagnosis and procedure codes, and charges applied to each stay, including room and nursing charges. Data were de‐identified prior to inclusion in the database, however encrypted identification numbers allowed for tracking individual patients across admissions. Data quality and reliability were assured through a joint effort between the Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA; Shawnee Mission, KS) and participating hospitals as described previously.13, 14 In accordance with the Common Rule (45 CFR 46.102(f)) and the policies of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board, this research, using a de‐identified dataset, was considered exempt from review.

Hospital Selection

Each year from 2004 to 2009, there were 18 hospitals participating in PHIS that reported data from both inpatient discharges and outpatient visits (including observation status discharges). To assess data quality for observation status stays, we evaluated observation status discharges for the presence of associated observation billing codes applied to charge records reported to PHIS including: 1) observation per hour, 2) ED observation time, or 3) other codes mentioning observation in the hospital charge master description document. The 16 hospitals with observation charges assigned to at least 90% of observation status discharges in each study year were selected for analysis.

Visit Identification

Within the 16 study hospitals, we identified all visits between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 with ED facility charges. From these ED visits, we included any stays designated by the hospital as observation or inpatient status, excluding transfers and ED discharges.

Variable Definitions

Hospitals submitting records to PHIS assigned a single patient type to the episode of care. The Observation patient type was assigned to patients discharged from observation status. Although the duration of observation is often less than 24 hours, hospitals may allow a patient to remain under observation for longer durations.15, 16 Duration of stay is not defined precisely enough within PHIS to determine hours of inpatient care. Therefore, length of stay (LOS) was not used to determine observation status stays.

The Inpatient patient type was assigned to patients who were discharged from inpatient status, including those patients admitted to inpatient care from the ED and also those who converted to inpatient status from observation. Patients who converted from observation status to inpatient status during the episode of care could be identified through the presence of observation charge codes as described above.

Given the potential for differences in the application of observation status, we also identified 1‐Day Stays where discharge occurred on the day of, or the day following, an inpatient status admission. These 1‐Day Stays represent hospitalizations that may, by their duration, be suitable for care in an observation unit. We considered discharges in the Observation and 1‐Day Stay categories to be Short‐Stays.

DATA ANALYSIS

For each of the 6 years of study, we calculated the following proportions to determine trends over time: 1) the number of Observation Status admissions from the ED as a proportion of the total number of ED visits resulting in Observation or Inpatient admission, and 2) the number of 1‐Day Stays admitted from the ED as a proportion of the total number of ED visits resulting in Observation or Inpatient admissions. Trends were analyzed using linear regression. Trends were also calculated for the total volume of admissions from the ED and the case‐mix index (CMI). CMI was assessed to evaluate for changes in the severity of illness for children admitted from the ED over the study period. Each hospital's CMI was calculated as an average of their Observation and Inpatient Status discharges' charge weights during the study period. Charge weights were calculated at the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR‐DRG)/severity of illness level (3M Health Information Systems, St Paul, MN) and were normalized national average charges derived by Thomson‐Reuters from their Pediatric Projected National Database. Weights were then assigned to each discharge based on the discharge's APR‐DRG and severity level assignment.

To assess the current outcomes for observation, we analyzed stays with associated observation billing codes from the most recent year of available data (2009). Stays with Observation patient type were considered to have been discharged from observation, while those with an Inpatient Status patient type were considered to have converted to an inpatient admission during the observation period.

Using the 2009 data, we calculated descriptive statistics for patient characteristics (eg, age, gender, payer) comparing Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions using chi‐square statistics. Age was categorized using the American Academy of Pediatrics groupings: <30 days, 30 days1 year, 12 years, 34 years, 512 years, 1317 years, >18 years. Designated payer was categorized into government, private, and other, including self‐pay and uninsured groups.

We used the Severity Classification Systems (SCS) developed for pediatric emergency care to estimate severity of illness for the visit.17 In this 5‐level system, each ICD‐9 diagnosis code is associated with a score related to the intensity of ED resources needed to care for a child with that diagnosis. In our analyses, each case was assigned the maximal SCS category based on the highest severity ICD‐9 code associated with the stay. Within the SCS, a score of 1 indicates minor illness (eg, diaper dermatitis) and 5 indicates major illness (eg, septic shock). The proportions of visits within categorical SCS scores were compared for Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions using chi‐square statistics.

We determined the top 10 ranking diagnoses for which children were admitted from the ED in 2009 using the Diagnosis Grouping System (DGS).18 The DGS was designed specifically to categorize pediatric ED visits into clinically meaningful groups. The ICD‐9 code for the principal discharge diagnosis was used to assign records to 1 of the 77 DGS subgroups. Within each of the top ranking DGS subgroups, we determined the proportion of Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions.

To provide clinically relevant outcomes of Observation Stays for common conditions, we selected stays with observation charges from within the top 10 ranking observation stay DGS subgroups in 2009. Outcomes for observation included: 1) immediate outcome of the observation stay (ie, discharge or conversion to inpatient status), 2) return visits to the ED in the 3 days following observation, and 3) readmissions to the hospital in the 3 and 30 days following observation. Bivariate comparisons of return visits and readmissions for Observation versus 1‐Day Stays within DGS subgroups were analyzed using chi‐square tests. Multivariate analyses of return visits and readmissions were conducted using Generalized Estimating Equations adjusting for severity of illness by SCS score and clustering by hospital. To account for local practice patterns, we also adjusted for a grouped treatment variable that included the site level proportion of children admitted to Observation Status, 1‐Day‐Stays, and longer Inpatient admissions. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC); P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Trends in Short‐Stays

An increase in proportion of Observation Stays was mirrored by a decrease in proportion of 1‐Day Stays over the study period (Figure 1). In 2009, there were 1.4 times more Observation Stays than 1‐Day Stays (25,653 vs 18,425) compared with 14,242 and 20,747, respectively, in 2004. This shift toward more Observation Stays occurred as hospitals faced a 16% increase in the total number of admissions from the ED (91,318 to 108,217) and change in CMI from 1.48 to 1.51. Over the study period, roughly 40% of all admissions from the ED were Short‐Stays (Observation and 1‐Day Stays). Median LOS for Observation Status stays was 1 day (interquartile range [IQR]: 11).

Patient Characteristics in 2009

Table 1 presents comparisons between Observation, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions. Of potential clinical significance, children under Observation Status were slightly younger (median, 4.0 years; IQR: 1.310.0) when compared with children admitted for 1‐Day Stays (median, 5.0 years; IQR: 1.411.4; P < 0.001) and longer‐duration Inpatient stays (median, 4.7 years; IQR: 0.912.2; P < 0.001). Nearly two‐thirds of Observation Status stays had SCS scores of 3 or lower compared with less than half of 1‐Day Stays and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions.

| Short‐Stays | LOS >1 Day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | 1‐Day Stay | Longer Admission | ||||

| N = 25,653* (24%) | N = 18,425* (17%) | P Value Comparing Observation to 1‐Day Stay | N = 64,139* (59%) | P Value Comparing Short‐Stays to LOS >1 Day | ||

| ||||||

| Sex | Male | 14,586 (57) | 10,474 (57) | P = 0.663 | 34,696 (54) | P < 0.001 |

| Female | 11,000 (43) | 7,940 (43) | 29,403 (46) | |||

| Payer | Government | 13,247 (58) | 8,944 (55) | P < 0.001 | 35,475 (61) | P < 0.001 |

| Private | 7,123 (31) | 5,105 (32) | 16,507 (28) | |||

| Other | 2,443 (11) | 2,087 (13) | 6,157 (11) | |||

| Age | <30 days | 793 (3) | 687 (4) | P < 0.001 | 3,932 (6) | P < 0.001 |

| 30 days1 yr | 4,499 (17) | 2,930 (16) | 13,139 (21) | |||

| 12 yr | 5,793 (23) | 3,566 (19) | 10,229 (16) | |||

| 34 yr | 3,040 (12) | 2,056 (11) | 5,551 (9) | |||

| 512 yr | 7,427 (29) | 5,570 (30) | 17,057 (27) | |||

| 1317 yr | 3,560 (14) | 3,136 (17) | 11,860 (18) | |||

| >17 yr | 541 (2) | 480 (3) | 2,371 (4) | |||

| Race | White | 17,249 (70) | 12,123 (70) | P < 0.001 | 40,779 (67) | P <0.001 |

| Black | 6,298 (25) | 4,216 (25) | 16,855 (28) | |||

| Asian | 277 (1) | 295 (2) | 995 (2) | |||

| Other | 885 (4) | 589 (3) | 2,011 (3) | |||

| SCS | 1 Minor illness | 64 (<1) | 37 (<1) | P < 0.001 | 84 (<1) | P < 0.001 |

| 2 | 1,190 (5) | 658 (4) | 1,461 (2) | |||

| 3 | 14,553 (57) | 7,617 (42) | 20,760 (33) | |||

| 4 | 8,994 (36) | 9,317 (51) | 35,632 (56) | |||

| 5 Major illness | 490 (2) | 579 (3) | 5,689 (9) | |||

In 2009, the top 10 DGS subgroups accounted for half of all admissions from the ED. The majority of admissions for extremity fractures, head trauma, dehydration, and asthma were Short‐Stays, as were roughly 50% of admissions for seizures, appendicitis, and gastroenteritis (Table 2). Respiratory infections and asthma were the top 1 and 2 ranking DGS subgroups for Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions. While rank order differed, 9 of the 10 top ranking Observation Stay DGS subgroups were also top ranking DGS subgroups for 1‐Day Stays. Gastroenteritis ranked 10th among Observation Stays and 11th among 1‐Day Stays. Diabetes mellitus ranked 26th among Observation Stays compared with 8th among 1‐Day Stays.

| Short‐Stays | LOS >1 Day | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % Observation | % 1‐Day Stay | % Longer Admission | |

| |||

| All admissions from the ED | 23.7 | 17.0 | 59.3 |

| n = 108,217 | |||

| Respiratory infections | 22.3 | 15.3 | 62.4 |

| n = 14,455 (13%) | |||

| Asthma | 32.0 | 23.8 | 44.2 |

| n = 8,853 (8%) | |||

| Other GI diseases | 24.1 | 16.2 | 59.7 |

| n = 6,519 (6%) | |||

| Appendicitis | 21.0 | 29.5 | 49.5 |

| n = 4,480 (4%) | |||

| Skin infections | 20.7 | 14.3 | 65.0 |

| n = 4,743 (4%) | |||

| Seizures | 29.5 | 22 | 48.5 |

| n = 4,088 (4%) | |||

| Extremity fractures | 49.4 | 20.5 | 30.1 |

| n = 3,681 (3%) | |||

| Dehydration | 37.8 | 19.0 | 43.2 |

| n = 2,773 (3%) | |||

| Gastroenteritis | 30.3 | 18.7 | 50.9 |

| n = 2,603 (2%) | |||

| Head trauma | 44.1 | 43.9 | 32.0 |

| n = 2,153 (2%) | |||

Average maximum SCS scores were clinically comparable for Observation and 1‐Day Stays and generally lower than for longer‐duration Inpatient admissions within the top 10 most common DGS subgroups. Average maximum SCS scores were statistically lower for Observation Stays compared with 1‐Day Stays for respiratory infections (3.2 vs 3.4), asthma (3.4 vs 3.6), diabetes (3.5 vs 3.8), gastroenteritis (3.0 vs 3.1), other gastrointestinal diseases (3.2 vs 3.4), head trauma (3.3 vs 3.5), and extremity fractures (3.2 vs 3.4) (P < 0.01). There were no differences in SCS scores for skin infections (SCS = 3.0) and appendicitis (SCS = 4.0) when comparing Observation and 1‐Day Stays.

Outcomes for Observation Stays in 2009

Within 6 of the top 10 DGS subgroups for Observation Stays, >75% of patients were discharged home from Observation Status (Table 3). Mean LOS for stays that converted from Observation to Inpatient Status ranged from 2.85 days for extremity fractures to 4.66 days for appendicitis.

| Return to ED in 3 Days n = 421 (1.6%) | Hospital Readmissions in 3 Days n = 247 (1.0%) | Hospital Readmissions in 30 Days n = 819 (3.2%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGS subgroup | % Discharged From Observation | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| ||||

| Respiratory infections | 72 | 1.1 (0.71.8) | 0.8 (0.51.3) | 0.9 (0.71.3) |

| Asthma | 80 | 1.3 (0.63.0) | 1.0 (0.61.8) | 0.5 (0.31.0) |

| Other GI diseases | 74 | 0.8 (0.51.3) | 2.2 (1.33.8) | 1.0 (0.71.5) |

| Appendicitis | 82 | NE | NE | NE |

| Skin infections | 68 | 1.8 (0.84.4) | 1.4 (0.45.3) | 0.9 (0.61.6) |

| Seizures | 79 | 0.8 (0.41.6) | 0.8 (0.31.8) | 0.7 (0.51.0) |

| Extremity fractures | 92 | 0.9 (0.42.1) | 0.2 (01.3) | 1.2 (0.53.2) |

| Dehydration | 81 | 0.9 (0.61.4) | 0.8 (0.31.9) | 0.7 (0.41.1) |

| Gastroenteritis | 74 | 0.9 (0.42.0) | 0.6 (0.41.2) | 0.6 (0.41) |

| Head trauma | 92 | 0.6 (0.21.7) | 0.3 (02.1) | 1.0 (0.42.8) |

Among children with Observation Stays for 1 of the top 10 DGS subgroups, adjusted return ED visit rates were <3% and readmission rates were <1.6% within 3 days following the index stay. Thirty‐day readmission rates were highest following observation for other GI illnesses and seizures. In unadjusted analysis, Observation Stays for asthma, respiratory infections, and skin infections were associated with greater proportions of return ED visits when compared with 1‐Day Stays. Differences were no longer statistically significant after adjusting for SCS score, clustering by hospital, and the grouped treatment variable. Adjusted odds of readmission were significantly higher at 3 days following observation for other GI illnesses and lower at 30 days following observation for seizures when compared with 1‐Day Stays (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this first, multicenter longitudinal study of pediatric observation following an ED visit, we found that Observation Status code utilization has increased steadily over the past 6 years and, in 2007, the proportion of children admitted to observation status surpassed the proportion of children experiencing a 1‐day inpatient admission. Taken together, Short‐Stays made up more than 40% of the hospital‐based care delivered to children admitted from an ED. Stable trends in CMI over time suggest that observation status may be replacing inpatient status designated care for pediatric Short‐Stays in these hospitals. Our findings suggest the lines between outpatient observation and short‐stay inpatient care are becoming increasingly blurred. These trends have occurred in the setting of changing policies for hospital reimbursement, requirements for patients to meet criteria to qualify for inpatient admissions, and efforts to avoid stays deemed unnecessary or inappropriate by their brief duration.19 Therefore there is a growing need to understand the impact of children under observation on the structure, delivery, and financing of acute hospital care for children.

Our results also have implications for pediatric health services research that relies on hospital administrative databases that do not contain observation stays. Currently, observation stays are systematically excluded from many inpatient administrative datasets.11, 12 Analyses of datasets that do not account for observation stays likely result in underestimation of hospitalization rates and hospital resource utilization for children. This may be particularly important for high‐volume conditions, such as asthma and acute infections, for which children commonly require brief periods of hospital‐based care beyond an ED encounter. Data from pediatric observation status admissions should be consistently included in hospital administrative datasets to allow for more comprehensive analyses of hospital resource utilization among children.

Prior research has shown that the diagnoses commonly treated in pediatric observation units overlap with the diagnoses for which children experience 1‐Day Stays.1, 20 We found a similar pattern of conditions for which children were under Observation Status and 1‐Day Stays with comparable severity of illness between the groups in terms of SCS scores. Our findings imply a need to determine how and why hospitals differentiate Observation Status from 1‐Day‐Stay groups in order to improve the assignment of observation status. Assuming continued pressures from payers to provide more care in outpatient or observation settings, there is potential for expansion of dedicated observation services for children in the US. Without designated observation units or processes to group patients with lower severity conditions, there may be limited opportunities to realize more efficient hospital care simply through the application of the label of observation status.

For more than 30 years, observation services have been provided to children who require a period of monitoring to determine their response to therapy and the need for acute inpatient admission from the ED.21While we were not able to determine the location of care for observation status patients in this study, we know that few children's hospitals have dedicated observation units and, even when an observation unit is present, not all observation status patients are cared for in dedicated observation units.9 This, in essence, means that most children under observation status are cared for in virtual observation by inpatient teams using inpatient beds. If observation patients are treated in inpatient beds and consume the same resources as inpatients, then cost‐savings based on reimbursement contracts with payers may not reflect an actual reduction in services. Pediatric institutions will need to closely monitor the financial implications of observation status given the historical differences in payment for observation and inpatient care.

With more than 70% of children being discharged home following observation, our results are comparable to the published literature2, 5, 6, 22, 23 and guidelines for observation unit operations.24 Similar to prior studies,4, 15, 2530 our results also indicate that return visits and readmissions following observation are uncommon events. Our findings can serve as initial benchmarks for condition‐specific outcomes for pediatric observation care. Studies are needed both to identify the clinical characteristics predictive of successful discharge home from observation and to explore the hospital‐to‐hospital variability in outcomes for observation. Such studies are necessary to identify the most successful healthcare delivery models for pediatric observation stays.

LIMITATIONS

The primary limitation to our results is that data from a subset of freestanding children's hospitals may not reflect observation stays at other children's hospitals or the community hospitals that care for children across the US. Only 18 of 42 current PHIS member hospitals have provided both outpatient visit and inpatient stay data for each year of the study period and were considered eligible. In an effort to ensure the quality of observation stay data, we included the 16 hospitals that assigned observation charges to at least 90% of their observation status stays in the PHIS database. The exclusion of the 2 hospitals where <90% of observation status patients were assigned observation charges likely resulted in an underestimation of the utilization of observation status.

Second, there is potential for misclassification of patient type given institutional variations in the assignment of patient status. The PHIS database does not contain information about the factors that were considered in the assignment of observation status. At the time of admission from the ED, observation or inpatient status is assigned. While this decision is clearly reserved for the admitting physician, the process is not standardized across hospitals.9 Some institutions have Utilization Managers on site to help guide decision‐making, while others allow the assignment to be made by physicians without specific guidance. As a result, some patients may be assigned to observation status at admission and reassigned to inpatient status following Utilization Review, which may bias our results toward overestimation of the number of observation stays that converted to inpatient status.

The third limitation to our results relates to return visits. An accurate assessment of return visits is subject to the patient returning to the same hospital. If children do not return to the same hospital, our results would underestimate return visits and readmissions. In addition, we did not assess the reason for return visit as there was no way to verify if the return visit was truly related to the index visit without detailed chart review. Assuming children return to the same hospital for different reasons, our results would overestimate return visits associated with observation stays. We suspect that many 3‐day return visits result from the progression of acute illness or failure to respond to initial treatment, and 30‐day readmissions reflect recurrent hospital care needs related to chronic illnesses.

Lastly, severity classification is difficult when analyzing administrative datasets without physiologic patient data, and the SCS may not provide enough detail to reveal clinically important differences between patient groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Short‐stay hospitalizations following ED visits are common among children, and the majority of pediatric short‐stays are under observation status. Analyses of inpatient administrative databases that exclude observation stays likely result in an underestimation of hospital resource utilization for children. Efforts are needed to ensure that patients under observation status are accounted for in hospital administrative datasets used for pediatric health services research, and healthcare resource allocation, as it relates to hospital‐based care. While the clinical outcomes for observation patients appear favorable in terms of conversion to inpatient admissions and return visits, the financial implications of observation status care within children's hospitals are currently unknown.

In recent decades, hospital lengths of stay have decreased and there has been a shift toward outpatient management for many pediatric conditions. In 2003, one‐third of all children admitted to US hospitals experienced 1‐day inpatient stays, an increase from 19% in 1993.1 Some hospitals have developed dedicated observation units for the care of children, with select diagnoses, who are expected to respond to less than 24 hours of treatment.26 Expansion of observation services has been suggested as an approach to lessen emergency department (ED) crowding7 and alleviate high‐capacity conditions within hospital inpatient units.8

In contrast to care delivered in a dedicated observation unit, observation status is an administrative label applied to patients who do not meet inpatient criteria as defined by third parties such as InterQual. While the decision to admit a patient is ultimately at the discretion of the ordering physician, many hospitals use predetermined criteria to assign observation status to patients admitted to observation and inpatient units.9 Treatment provided under observation status is designated by hospitals and payers as outpatient care, even when delivered in an inpatient bed.10 As outpatient‐designated care, observation cases do not enter publicly available administrative datasets of hospital discharges that have traditionally been used to understand hospital resource utilization, including the National Hospital Discharge Survey and the Kid's Inpatient Database.11, 12

We hypothesize that there has been an increase in observation status care delivered to children in recent years, and that the majority of children under observation were discharged home without converting to inpatient status. To determine trends in pediatric observation status care, we conducted the first longitudinal, multicenter evaluation of observation status code utilization following ED treatment in a sample of US freestanding children's hospitals. In addition, we focused on the most recent year of data among top ranking diagnoses to assess the current state of observation status stay outcomes (including conversion to inpatient status and return visits).

METHODS

Data Source

Data for this multicenter retrospective cohort study were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). Freestanding children's hospital's participating in PHIS account for approximately 20% of all US tertiary care children's hospitals. The PHIS hospitals provide resource utilization data including patient demographics, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) diagnosis and procedure codes, and charges applied to each stay, including room and nursing charges. Data were de‐identified prior to inclusion in the database, however encrypted identification numbers allowed for tracking individual patients across admissions. Data quality and reliability were assured through a joint effort between the Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA; Shawnee Mission, KS) and participating hospitals as described previously.13, 14 In accordance with the Common Rule (45 CFR 46.102(f)) and the policies of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board, this research, using a de‐identified dataset, was considered exempt from review.

Hospital Selection

Each year from 2004 to 2009, there were 18 hospitals participating in PHIS that reported data from both inpatient discharges and outpatient visits (including observation status discharges). To assess data quality for observation status stays, we evaluated observation status discharges for the presence of associated observation billing codes applied to charge records reported to PHIS including: 1) observation per hour, 2) ED observation time, or 3) other codes mentioning observation in the hospital charge master description document. The 16 hospitals with observation charges assigned to at least 90% of observation status discharges in each study year were selected for analysis.

Visit Identification

Within the 16 study hospitals, we identified all visits between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 with ED facility charges. From these ED visits, we included any stays designated by the hospital as observation or inpatient status, excluding transfers and ED discharges.

Variable Definitions

Hospitals submitting records to PHIS assigned a single patient type to the episode of care. The Observation patient type was assigned to patients discharged from observation status. Although the duration of observation is often less than 24 hours, hospitals may allow a patient to remain under observation for longer durations.15, 16 Duration of stay is not defined precisely enough within PHIS to determine hours of inpatient care. Therefore, length of stay (LOS) was not used to determine observation status stays.

The Inpatient patient type was assigned to patients who were discharged from inpatient status, including those patients admitted to inpatient care from the ED and also those who converted to inpatient status from observation. Patients who converted from observation status to inpatient status during the episode of care could be identified through the presence of observation charge codes as described above.

Given the potential for differences in the application of observation status, we also identified 1‐Day Stays where discharge occurred on the day of, or the day following, an inpatient status admission. These 1‐Day Stays represent hospitalizations that may, by their duration, be suitable for care in an observation unit. We considered discharges in the Observation and 1‐Day Stay categories to be Short‐Stays.

DATA ANALYSIS

For each of the 6 years of study, we calculated the following proportions to determine trends over time: 1) the number of Observation Status admissions from the ED as a proportion of the total number of ED visits resulting in Observation or Inpatient admission, and 2) the number of 1‐Day Stays admitted from the ED as a proportion of the total number of ED visits resulting in Observation or Inpatient admissions. Trends were analyzed using linear regression. Trends were also calculated for the total volume of admissions from the ED and the case‐mix index (CMI). CMI was assessed to evaluate for changes in the severity of illness for children admitted from the ED over the study period. Each hospital's CMI was calculated as an average of their Observation and Inpatient Status discharges' charge weights during the study period. Charge weights were calculated at the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR‐DRG)/severity of illness level (3M Health Information Systems, St Paul, MN) and were normalized national average charges derived by Thomson‐Reuters from their Pediatric Projected National Database. Weights were then assigned to each discharge based on the discharge's APR‐DRG and severity level assignment.

To assess the current outcomes for observation, we analyzed stays with associated observation billing codes from the most recent year of available data (2009). Stays with Observation patient type were considered to have been discharged from observation, while those with an Inpatient Status patient type were considered to have converted to an inpatient admission during the observation period.

Using the 2009 data, we calculated descriptive statistics for patient characteristics (eg, age, gender, payer) comparing Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions using chi‐square statistics. Age was categorized using the American Academy of Pediatrics groupings: <30 days, 30 days1 year, 12 years, 34 years, 512 years, 1317 years, >18 years. Designated payer was categorized into government, private, and other, including self‐pay and uninsured groups.

We used the Severity Classification Systems (SCS) developed for pediatric emergency care to estimate severity of illness for the visit.17 In this 5‐level system, each ICD‐9 diagnosis code is associated with a score related to the intensity of ED resources needed to care for a child with that diagnosis. In our analyses, each case was assigned the maximal SCS category based on the highest severity ICD‐9 code associated with the stay. Within the SCS, a score of 1 indicates minor illness (eg, diaper dermatitis) and 5 indicates major illness (eg, septic shock). The proportions of visits within categorical SCS scores were compared for Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions using chi‐square statistics.

We determined the top 10 ranking diagnoses for which children were admitted from the ED in 2009 using the Diagnosis Grouping System (DGS).18 The DGS was designed specifically to categorize pediatric ED visits into clinically meaningful groups. The ICD‐9 code for the principal discharge diagnosis was used to assign records to 1 of the 77 DGS subgroups. Within each of the top ranking DGS subgroups, we determined the proportion of Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions.

To provide clinically relevant outcomes of Observation Stays for common conditions, we selected stays with observation charges from within the top 10 ranking observation stay DGS subgroups in 2009. Outcomes for observation included: 1) immediate outcome of the observation stay (ie, discharge or conversion to inpatient status), 2) return visits to the ED in the 3 days following observation, and 3) readmissions to the hospital in the 3 and 30 days following observation. Bivariate comparisons of return visits and readmissions for Observation versus 1‐Day Stays within DGS subgroups were analyzed using chi‐square tests. Multivariate analyses of return visits and readmissions were conducted using Generalized Estimating Equations adjusting for severity of illness by SCS score and clustering by hospital. To account for local practice patterns, we also adjusted for a grouped treatment variable that included the site level proportion of children admitted to Observation Status, 1‐Day‐Stays, and longer Inpatient admissions. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC); P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Trends in Short‐Stays

An increase in proportion of Observation Stays was mirrored by a decrease in proportion of 1‐Day Stays over the study period (Figure 1). In 2009, there were 1.4 times more Observation Stays than 1‐Day Stays (25,653 vs 18,425) compared with 14,242 and 20,747, respectively, in 2004. This shift toward more Observation Stays occurred as hospitals faced a 16% increase in the total number of admissions from the ED (91,318 to 108,217) and change in CMI from 1.48 to 1.51. Over the study period, roughly 40% of all admissions from the ED were Short‐Stays (Observation and 1‐Day Stays). Median LOS for Observation Status stays was 1 day (interquartile range [IQR]: 11).

Patient Characteristics in 2009

Table 1 presents comparisons between Observation, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions. Of potential clinical significance, children under Observation Status were slightly younger (median, 4.0 years; IQR: 1.310.0) when compared with children admitted for 1‐Day Stays (median, 5.0 years; IQR: 1.411.4; P < 0.001) and longer‐duration Inpatient stays (median, 4.7 years; IQR: 0.912.2; P < 0.001). Nearly two‐thirds of Observation Status stays had SCS scores of 3 or lower compared with less than half of 1‐Day Stays and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions.

| Short‐Stays | LOS >1 Day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | 1‐Day Stay | Longer Admission | ||||

| N = 25,653* (24%) | N = 18,425* (17%) | P Value Comparing Observation to 1‐Day Stay | N = 64,139* (59%) | P Value Comparing Short‐Stays to LOS >1 Day | ||

| ||||||

| Sex | Male | 14,586 (57) | 10,474 (57) | P = 0.663 | 34,696 (54) | P < 0.001 |

| Female | 11,000 (43) | 7,940 (43) | 29,403 (46) | |||

| Payer | Government | 13,247 (58) | 8,944 (55) | P < 0.001 | 35,475 (61) | P < 0.001 |

| Private | 7,123 (31) | 5,105 (32) | 16,507 (28) | |||

| Other | 2,443 (11) | 2,087 (13) | 6,157 (11) | |||

| Age | <30 days | 793 (3) | 687 (4) | P < 0.001 | 3,932 (6) | P < 0.001 |

| 30 days1 yr | 4,499 (17) | 2,930 (16) | 13,139 (21) | |||

| 12 yr | 5,793 (23) | 3,566 (19) | 10,229 (16) | |||

| 34 yr | 3,040 (12) | 2,056 (11) | 5,551 (9) | |||

| 512 yr | 7,427 (29) | 5,570 (30) | 17,057 (27) | |||

| 1317 yr | 3,560 (14) | 3,136 (17) | 11,860 (18) | |||

| >17 yr | 541 (2) | 480 (3) | 2,371 (4) | |||

| Race | White | 17,249 (70) | 12,123 (70) | P < 0.001 | 40,779 (67) | P <0.001 |

| Black | 6,298 (25) | 4,216 (25) | 16,855 (28) | |||

| Asian | 277 (1) | 295 (2) | 995 (2) | |||

| Other | 885 (4) | 589 (3) | 2,011 (3) | |||

| SCS | 1 Minor illness | 64 (<1) | 37 (<1) | P < 0.001 | 84 (<1) | P < 0.001 |

| 2 | 1,190 (5) | 658 (4) | 1,461 (2) | |||

| 3 | 14,553 (57) | 7,617 (42) | 20,760 (33) | |||

| 4 | 8,994 (36) | 9,317 (51) | 35,632 (56) | |||

| 5 Major illness | 490 (2) | 579 (3) | 5,689 (9) | |||

In 2009, the top 10 DGS subgroups accounted for half of all admissions from the ED. The majority of admissions for extremity fractures, head trauma, dehydration, and asthma were Short‐Stays, as were roughly 50% of admissions for seizures, appendicitis, and gastroenteritis (Table 2). Respiratory infections and asthma were the top 1 and 2 ranking DGS subgroups for Observation Stays, 1‐Day Stays, and longer‐duration Inpatient admissions. While rank order differed, 9 of the 10 top ranking Observation Stay DGS subgroups were also top ranking DGS subgroups for 1‐Day Stays. Gastroenteritis ranked 10th among Observation Stays and 11th among 1‐Day Stays. Diabetes mellitus ranked 26th among Observation Stays compared with 8th among 1‐Day Stays.

| Short‐Stays | LOS >1 Day | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % Observation | % 1‐Day Stay | % Longer Admission | |

| |||

| All admissions from the ED | 23.7 | 17.0 | 59.3 |

| n = 108,217 | |||

| Respiratory infections | 22.3 | 15.3 | 62.4 |

| n = 14,455 (13%) | |||

| Asthma | 32.0 | 23.8 | 44.2 |

| n = 8,853 (8%) | |||

| Other GI diseases | 24.1 | 16.2 | 59.7 |

| n = 6,519 (6%) | |||

| Appendicitis | 21.0 | 29.5 | 49.5 |

| n = 4,480 (4%) | |||

| Skin infections | 20.7 | 14.3 | 65.0 |

| n = 4,743 (4%) | |||

| Seizures | 29.5 | 22 | 48.5 |

| n = 4,088 (4%) | |||

| Extremity fractures | 49.4 | 20.5 | 30.1 |

| n = 3,681 (3%) | |||

| Dehydration | 37.8 | 19.0 | 43.2 |

| n = 2,773 (3%) | |||

| Gastroenteritis | 30.3 | 18.7 | 50.9 |

| n = 2,603 (2%) | |||

| Head trauma | 44.1 | 43.9 | 32.0 |

| n = 2,153 (2%) | |||

Average maximum SCS scores were clinically comparable for Observation and 1‐Day Stays and generally lower than for longer‐duration Inpatient admissions within the top 10 most common DGS subgroups. Average maximum SCS scores were statistically lower for Observation Stays compared with 1‐Day Stays for respiratory infections (3.2 vs 3.4), asthma (3.4 vs 3.6), diabetes (3.5 vs 3.8), gastroenteritis (3.0 vs 3.1), other gastrointestinal diseases (3.2 vs 3.4), head trauma (3.3 vs 3.5), and extremity fractures (3.2 vs 3.4) (P < 0.01). There were no differences in SCS scores for skin infections (SCS = 3.0) and appendicitis (SCS = 4.0) when comparing Observation and 1‐Day Stays.

Outcomes for Observation Stays in 2009

Within 6 of the top 10 DGS subgroups for Observation Stays, >75% of patients were discharged home from Observation Status (Table 3). Mean LOS for stays that converted from Observation to Inpatient Status ranged from 2.85 days for extremity fractures to 4.66 days for appendicitis.

| Return to ED in 3 Days n = 421 (1.6%) | Hospital Readmissions in 3 Days n = 247 (1.0%) | Hospital Readmissions in 30 Days n = 819 (3.2%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGS subgroup | % Discharged From Observation | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| ||||

| Respiratory infections | 72 | 1.1 (0.71.8) | 0.8 (0.51.3) | 0.9 (0.71.3) |

| Asthma | 80 | 1.3 (0.63.0) | 1.0 (0.61.8) | 0.5 (0.31.0) |

| Other GI diseases | 74 | 0.8 (0.51.3) | 2.2 (1.33.8) | 1.0 (0.71.5) |

| Appendicitis | 82 | NE | NE | NE |

| Skin infections | 68 | 1.8 (0.84.4) | 1.4 (0.45.3) | 0.9 (0.61.6) |

| Seizures | 79 | 0.8 (0.41.6) | 0.8 (0.31.8) | 0.7 (0.51.0) |

| Extremity fractures | 92 | 0.9 (0.42.1) | 0.2 (01.3) | 1.2 (0.53.2) |

| Dehydration | 81 | 0.9 (0.61.4) | 0.8 (0.31.9) | 0.7 (0.41.1) |

| Gastroenteritis | 74 | 0.9 (0.42.0) | 0.6 (0.41.2) | 0.6 (0.41) |

| Head trauma | 92 | 0.6 (0.21.7) | 0.3 (02.1) | 1.0 (0.42.8) |

Among children with Observation Stays for 1 of the top 10 DGS subgroups, adjusted return ED visit rates were <3% and readmission rates were <1.6% within 3 days following the index stay. Thirty‐day readmission rates were highest following observation for other GI illnesses and seizures. In unadjusted analysis, Observation Stays for asthma, respiratory infections, and skin infections were associated with greater proportions of return ED visits when compared with 1‐Day Stays. Differences were no longer statistically significant after adjusting for SCS score, clustering by hospital, and the grouped treatment variable. Adjusted odds of readmission were significantly higher at 3 days following observation for other GI illnesses and lower at 30 days following observation for seizures when compared with 1‐Day Stays (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this first, multicenter longitudinal study of pediatric observation following an ED visit, we found that Observation Status code utilization has increased steadily over the past 6 years and, in 2007, the proportion of children admitted to observation status surpassed the proportion of children experiencing a 1‐day inpatient admission. Taken together, Short‐Stays made up more than 40% of the hospital‐based care delivered to children admitted from an ED. Stable trends in CMI over time suggest that observation status may be replacing inpatient status designated care for pediatric Short‐Stays in these hospitals. Our findings suggest the lines between outpatient observation and short‐stay inpatient care are becoming increasingly blurred. These trends have occurred in the setting of changing policies for hospital reimbursement, requirements for patients to meet criteria to qualify for inpatient admissions, and efforts to avoid stays deemed unnecessary or inappropriate by their brief duration.19 Therefore there is a growing need to understand the impact of children under observation on the structure, delivery, and financing of acute hospital care for children.

Our results also have implications for pediatric health services research that relies on hospital administrative databases that do not contain observation stays. Currently, observation stays are systematically excluded from many inpatient administrative datasets.11, 12 Analyses of datasets that do not account for observation stays likely result in underestimation of hospitalization rates and hospital resource utilization for children. This may be particularly important for high‐volume conditions, such as asthma and acute infections, for which children commonly require brief periods of hospital‐based care beyond an ED encounter. Data from pediatric observation status admissions should be consistently included in hospital administrative datasets to allow for more comprehensive analyses of hospital resource utilization among children.

Prior research has shown that the diagnoses commonly treated in pediatric observation units overlap with the diagnoses for which children experience 1‐Day Stays.1, 20 We found a similar pattern of conditions for which children were under Observation Status and 1‐Day Stays with comparable severity of illness between the groups in terms of SCS scores. Our findings imply a need to determine how and why hospitals differentiate Observation Status from 1‐Day‐Stay groups in order to improve the assignment of observation status. Assuming continued pressures from payers to provide more care in outpatient or observation settings, there is potential for expansion of dedicated observation services for children in the US. Without designated observation units or processes to group patients with lower severity conditions, there may be limited opportunities to realize more efficient hospital care simply through the application of the label of observation status.

For more than 30 years, observation services have been provided to children who require a period of monitoring to determine their response to therapy and the need for acute inpatient admission from the ED.21While we were not able to determine the location of care for observation status patients in this study, we know that few children's hospitals have dedicated observation units and, even when an observation unit is present, not all observation status patients are cared for in dedicated observation units.9 This, in essence, means that most children under observation status are cared for in virtual observation by inpatient teams using inpatient beds. If observation patients are treated in inpatient beds and consume the same resources as inpatients, then cost‐savings based on reimbursement contracts with payers may not reflect an actual reduction in services. Pediatric institutions will need to closely monitor the financial implications of observation status given the historical differences in payment for observation and inpatient care.