User login

What Is Your Diagnosis? Verrucous Carcinoma

An 81-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a nodule on the right labia majora that had been present for 1 year. She had a history of intertriginous psoriasis, and several biopsies were performed at an outside facility over the last 5 years that revealed psoriasis but were otherwise noncontributory. Physical examination revealed erythema and scaling on the buttocks with maceration in the intertriginous area (top) and the perineum associated with a verrucous nodule (bottom).

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Carcinoma

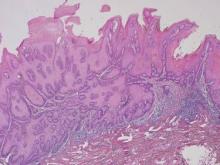

Biopsies of early lesions often may be difficult to interpret without clinicopathological correlation. Our patient’s tumor was associated with intertriginous psoriasis, which was the only abnormality previously noted on superficial biopsies performed at an outside facility. The patient was scheduled for an excisional biopsy due to the large tumor size and clinical suspicion that the prior biopsies were inadequate and failed to demonstrate the primary underlying pathology. Excisional biopsy of the verrucous tumor revealed epithelium composed of keratinocytes with glassy cytoplasm. Papillomatosis was noted along with an endophytic component of well-differentiated epithelial cells extending into the dermis in a bulbous pattern consistent with the verrucous carcinoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(Figure). Verrucous carcinoma often requires correlation with both the clinical and histopathologic findings for definitive diagnosis, as keratinocytes often appear to be well differentiated.1

Verrucous carcinoma may begin as an innocuous papule that slowly grows into a large fungating tumor. Verrucous carcinomas typically are slow growing, exophytic, and low grade. The etiology of verrucous carcinoma is not clear, and the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is controversial.2 Best classified as a well-differentiated SCC, verrucous carcinoma rarely metastasizes but may invade adjacent tissues.

Differential diagnoses include a giant inflamed seborrheic keratosis, condyloma acuminatum, rupioid psoriasis, and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). Although large and inflamed seborrheic keratoses may have squamous eddies that mimic SCC, seborrheic keratoses do not invade the dermis and typically have a well-circumscribed stuck-on appearance. Abnormal mitotic figures are not identified. Condylomas are genital warts caused by HPV infection that often are clustered, well circumscribed, and exophytic. Large lesions can be difficult to distinguish from verrucous carcinomas, and biopsy generally reveals koilocytes identified by perinuclear clearing and raisinlike nuclei. Immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization studies can be of value in diagnosis and in identifying those lesions that are at high risk for malignant transformation. High-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, and HPV-39, as well as other types, whereas low-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-42, and others.2 Differentiating squamous cell hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in situ also can be aided by immunohistochemistry. Squamous cell hyperplasia is usually negative for INK4 p16Ink4A and p53 and exhibits variable Ki-67 staining. Differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in situ exhibits a profile that is p16Ink4A negative, Ki-67 positive, and exhibits variable p53 staining.3 Basaloid and warty intraepithelial neoplasia is consistently p16Ink4A positive, Ki-67 positive, and variably positive for p53.3 Therefore, p16 staining of high-grade areas is a useful biomarker that can help establish diagnosis of associated squamous cell carcinoma.4 The role of papillomaviruses in the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer is an area of active study, and research suggests that papillomaviruses may have a much greater role than previously suspected.5

At times, psoriasis may be markedly hyperkeratotic, clinically mimicking a verrucous neoplasm. This hyperkeratotic type of psoriasis is known as rupioid psoriasis. However, these psoriatic lesions are exophytic, are associated with spongiform pustules, and lack the atypia and endophytic pattern typically seen with verrucous carcinoma. An ILVEN also lacks atypia and an endophytic pattern and usually presents in childhood as a persistent linear plaque, rather than the verrucous plaque noted in our patient. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in the setting of verrucoid ILVEN but is exceptionally uncommon.6

Successful treatment of verrucous carcinoma is best achieved by complete excision. Oral retinoids and immunomodulators such as imiquimod also may be of value.7 Our patient’s tumor qualifies as T2N0M0 because it was greater than 2 cm in size.8 A Breslow thickness of 2 mm or greater and Clark level IV are high-risk features associated with a worse prognosis, but clinical evaluation of our patient’s lymph nodes was unremarkable and no distant metastases were identified. Our patient continues to do well with no evidence of recurrence.

1. Bambao C, Nofech-Mozes S, Shier M. Giant condyloma versus verrucous carcinoma: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:230-233.

2. Asiaf A, Ahmad ST, Mohannad SO, et al. Review of the current knowledge on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of human papillomavirus infection. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:206-224.

3. Chaux A, Pfannl R, Rodríguez IM, et al. Distinctive immunohistochemical profile of penile intraepithelial lesions: a study of 74 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:553-562.

4. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266-1297.

5. Aldabagh B, Angeles J, Cardones AR, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and human papillomavirus: is there an association? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1-23.

6. Turk BG, Ertam I, Urkmez A, et al. Development of squamous cell carcinoma on an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus in the genital area. Cutis. 2012;89:273-275.

7. Erkek E, Basar H, Bozdogan O, et al. Giant condyloma acuminata of Buschke-Löwenstein: successful treatment with a combination of surgical excision, oral acitretin and topical imiquimod. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:366-368.

8. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301-314.

An 81-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a nodule on the right labia majora that had been present for 1 year. She had a history of intertriginous psoriasis, and several biopsies were performed at an outside facility over the last 5 years that revealed psoriasis but were otherwise noncontributory. Physical examination revealed erythema and scaling on the buttocks with maceration in the intertriginous area (top) and the perineum associated with a verrucous nodule (bottom).

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Carcinoma

Biopsies of early lesions often may be difficult to interpret without clinicopathological correlation. Our patient’s tumor was associated with intertriginous psoriasis, which was the only abnormality previously noted on superficial biopsies performed at an outside facility. The patient was scheduled for an excisional biopsy due to the large tumor size and clinical suspicion that the prior biopsies were inadequate and failed to demonstrate the primary underlying pathology. Excisional biopsy of the verrucous tumor revealed epithelium composed of keratinocytes with glassy cytoplasm. Papillomatosis was noted along with an endophytic component of well-differentiated epithelial cells extending into the dermis in a bulbous pattern consistent with the verrucous carcinoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(Figure). Verrucous carcinoma often requires correlation with both the clinical and histopathologic findings for definitive diagnosis, as keratinocytes often appear to be well differentiated.1

Verrucous carcinoma may begin as an innocuous papule that slowly grows into a large fungating tumor. Verrucous carcinomas typically are slow growing, exophytic, and low grade. The etiology of verrucous carcinoma is not clear, and the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is controversial.2 Best classified as a well-differentiated SCC, verrucous carcinoma rarely metastasizes but may invade adjacent tissues.

Differential diagnoses include a giant inflamed seborrheic keratosis, condyloma acuminatum, rupioid psoriasis, and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). Although large and inflamed seborrheic keratoses may have squamous eddies that mimic SCC, seborrheic keratoses do not invade the dermis and typically have a well-circumscribed stuck-on appearance. Abnormal mitotic figures are not identified. Condylomas are genital warts caused by HPV infection that often are clustered, well circumscribed, and exophytic. Large lesions can be difficult to distinguish from verrucous carcinomas, and biopsy generally reveals koilocytes identified by perinuclear clearing and raisinlike nuclei. Immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization studies can be of value in diagnosis and in identifying those lesions that are at high risk for malignant transformation. High-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, and HPV-39, as well as other types, whereas low-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-42, and others.2 Differentiating squamous cell hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in situ also can be aided by immunohistochemistry. Squamous cell hyperplasia is usually negative for INK4 p16Ink4A and p53 and exhibits variable Ki-67 staining. Differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in situ exhibits a profile that is p16Ink4A negative, Ki-67 positive, and exhibits variable p53 staining.3 Basaloid and warty intraepithelial neoplasia is consistently p16Ink4A positive, Ki-67 positive, and variably positive for p53.3 Therefore, p16 staining of high-grade areas is a useful biomarker that can help establish diagnosis of associated squamous cell carcinoma.4 The role of papillomaviruses in the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer is an area of active study, and research suggests that papillomaviruses may have a much greater role than previously suspected.5

At times, psoriasis may be markedly hyperkeratotic, clinically mimicking a verrucous neoplasm. This hyperkeratotic type of psoriasis is known as rupioid psoriasis. However, these psoriatic lesions are exophytic, are associated with spongiform pustules, and lack the atypia and endophytic pattern typically seen with verrucous carcinoma. An ILVEN also lacks atypia and an endophytic pattern and usually presents in childhood as a persistent linear plaque, rather than the verrucous plaque noted in our patient. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in the setting of verrucoid ILVEN but is exceptionally uncommon.6

Successful treatment of verrucous carcinoma is best achieved by complete excision. Oral retinoids and immunomodulators such as imiquimod also may be of value.7 Our patient’s tumor qualifies as T2N0M0 because it was greater than 2 cm in size.8 A Breslow thickness of 2 mm or greater and Clark level IV are high-risk features associated with a worse prognosis, but clinical evaluation of our patient’s lymph nodes was unremarkable and no distant metastases were identified. Our patient continues to do well with no evidence of recurrence.

An 81-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a nodule on the right labia majora that had been present for 1 year. She had a history of intertriginous psoriasis, and several biopsies were performed at an outside facility over the last 5 years that revealed psoriasis but were otherwise noncontributory. Physical examination revealed erythema and scaling on the buttocks with maceration in the intertriginous area (top) and the perineum associated with a verrucous nodule (bottom).

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Carcinoma

Biopsies of early lesions often may be difficult to interpret without clinicopathological correlation. Our patient’s tumor was associated with intertriginous psoriasis, which was the only abnormality previously noted on superficial biopsies performed at an outside facility. The patient was scheduled for an excisional biopsy due to the large tumor size and clinical suspicion that the prior biopsies were inadequate and failed to demonstrate the primary underlying pathology. Excisional biopsy of the verrucous tumor revealed epithelium composed of keratinocytes with glassy cytoplasm. Papillomatosis was noted along with an endophytic component of well-differentiated epithelial cells extending into the dermis in a bulbous pattern consistent with the verrucous carcinoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(Figure). Verrucous carcinoma often requires correlation with both the clinical and histopathologic findings for definitive diagnosis, as keratinocytes often appear to be well differentiated.1

Verrucous carcinoma may begin as an innocuous papule that slowly grows into a large fungating tumor. Verrucous carcinomas typically are slow growing, exophytic, and low grade. The etiology of verrucous carcinoma is not clear, and the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is controversial.2 Best classified as a well-differentiated SCC, verrucous carcinoma rarely metastasizes but may invade adjacent tissues.

Differential diagnoses include a giant inflamed seborrheic keratosis, condyloma acuminatum, rupioid psoriasis, and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). Although large and inflamed seborrheic keratoses may have squamous eddies that mimic SCC, seborrheic keratoses do not invade the dermis and typically have a well-circumscribed stuck-on appearance. Abnormal mitotic figures are not identified. Condylomas are genital warts caused by HPV infection that often are clustered, well circumscribed, and exophytic. Large lesions can be difficult to distinguish from verrucous carcinomas, and biopsy generally reveals koilocytes identified by perinuclear clearing and raisinlike nuclei. Immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization studies can be of value in diagnosis and in identifying those lesions that are at high risk for malignant transformation. High-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, and HPV-39, as well as other types, whereas low-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-42, and others.2 Differentiating squamous cell hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in situ also can be aided by immunohistochemistry. Squamous cell hyperplasia is usually negative for INK4 p16Ink4A and p53 and exhibits variable Ki-67 staining. Differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in situ exhibits a profile that is p16Ink4A negative, Ki-67 positive, and exhibits variable p53 staining.3 Basaloid and warty intraepithelial neoplasia is consistently p16Ink4A positive, Ki-67 positive, and variably positive for p53.3 Therefore, p16 staining of high-grade areas is a useful biomarker that can help establish diagnosis of associated squamous cell carcinoma.4 The role of papillomaviruses in the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer is an area of active study, and research suggests that papillomaviruses may have a much greater role than previously suspected.5

At times, psoriasis may be markedly hyperkeratotic, clinically mimicking a verrucous neoplasm. This hyperkeratotic type of psoriasis is known as rupioid psoriasis. However, these psoriatic lesions are exophytic, are associated with spongiform pustules, and lack the atypia and endophytic pattern typically seen with verrucous carcinoma. An ILVEN also lacks atypia and an endophytic pattern and usually presents in childhood as a persistent linear plaque, rather than the verrucous plaque noted in our patient. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in the setting of verrucoid ILVEN but is exceptionally uncommon.6

Successful treatment of verrucous carcinoma is best achieved by complete excision. Oral retinoids and immunomodulators such as imiquimod also may be of value.7 Our patient’s tumor qualifies as T2N0M0 because it was greater than 2 cm in size.8 A Breslow thickness of 2 mm or greater and Clark level IV are high-risk features associated with a worse prognosis, but clinical evaluation of our patient’s lymph nodes was unremarkable and no distant metastases were identified. Our patient continues to do well with no evidence of recurrence.

1. Bambao C, Nofech-Mozes S, Shier M. Giant condyloma versus verrucous carcinoma: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:230-233.

2. Asiaf A, Ahmad ST, Mohannad SO, et al. Review of the current knowledge on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of human papillomavirus infection. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:206-224.

3. Chaux A, Pfannl R, Rodríguez IM, et al. Distinctive immunohistochemical profile of penile intraepithelial lesions: a study of 74 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:553-562.

4. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266-1297.

5. Aldabagh B, Angeles J, Cardones AR, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and human papillomavirus: is there an association? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1-23.

6. Turk BG, Ertam I, Urkmez A, et al. Development of squamous cell carcinoma on an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus in the genital area. Cutis. 2012;89:273-275.

7. Erkek E, Basar H, Bozdogan O, et al. Giant condyloma acuminata of Buschke-Löwenstein: successful treatment with a combination of surgical excision, oral acitretin and topical imiquimod. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:366-368.

8. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301-314.

1. Bambao C, Nofech-Mozes S, Shier M. Giant condyloma versus verrucous carcinoma: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:230-233.

2. Asiaf A, Ahmad ST, Mohannad SO, et al. Review of the current knowledge on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of human papillomavirus infection. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:206-224.

3. Chaux A, Pfannl R, Rodríguez IM, et al. Distinctive immunohistochemical profile of penile intraepithelial lesions: a study of 74 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:553-562.

4. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266-1297.

5. Aldabagh B, Angeles J, Cardones AR, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and human papillomavirus: is there an association? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1-23.

6. Turk BG, Ertam I, Urkmez A, et al. Development of squamous cell carcinoma on an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus in the genital area. Cutis. 2012;89:273-275.

7. Erkek E, Basar H, Bozdogan O, et al. Giant condyloma acuminata of Buschke-Löwenstein: successful treatment with a combination of surgical excision, oral acitretin and topical imiquimod. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:366-368.

8. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301-314.

Patchy hair loss on the scalp

A 12-year-old girl has a large, irregular area of hair loss over the central frontoparietal scalp. Physical examination reveals scattered short hairs of varying lengths and a few small crusts throughout the area of alopecia (Figure 1). The remainder of the scalp appears normal.

Q: Which diagnosis is most likely?

- Alopecia areata

- Lichen planopilaris

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Trichotillomania

- Follicular degeneration syndrome

A: The correct answer is trichotillomania, the compulsive pulling out of one’s own hair. Irregularly shaped areas of alopecia containing short hairs of varied lengths and excoriation should raise clinical suspicion of trichotillomania. Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis when follicles devoid of hair shafts, hemorrhage, and misshapen fragments of scalp hair (pigment casts) are seen.

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Trichotillomania may present as striking hair loss (alopecia) with an irregular pattern, often with sharp angles or scalloped borders.1 Short and broken hairs within involved areas are typically seen because regenerating hairs are too short to be grasped and pulled out.2 Although hair loss on the scalp may be most evident, hair loss on any hair-bearing area of the body may be noted, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Family members and the affected individual are often aware of compulsive manipulation of hair.

Depression, anxiety, and other grooming behaviors such as skin-picking and nail-biting may be associated with trichotillomania. Affected individuals often feel a sense of gratification from pulling out hairs. Although systemic complications are rare, some individuals ingest the removed hairs (trichophagy), and the hairs may be caught in the gastric folds and eventually form a trichobezoar.3

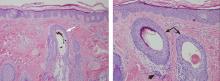

The diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings and by asking the patient about hair-pulling. Asking the patient if the habit is due to the feel of the hair, a need to calm himself or herself, or other factors may be revealing. The majority of cases can be diagnosed without biopsy. Biopsy from affected areas reveals changes related to trauma such as empty hair follicles, hemorrhage, and hair shaft fragments in the dermis2 (Figure 2). The number of catagen follicles is increased. Other causes of patchy alopecia are associated with different findings on biopsy.

Alopecia areata may be associated with an increased number of catagen hairs but is characterized by a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate.

Biopsy of lichen planopilaris typically reveals vacuolar changes along the dermal-follicular junction and necrotic keratinocytes.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is associated with thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased mucin in the dermis, follicular plugging by keratin, and vacuolar changes along the dermal-epidermal junction.

Biopsy of follicular degeneration syndrome exhibits premature desquamation of the internal root sheath as well as an increased number of fibrous tracts marking the sites of lost hairs.

The etiology of trichotillomania remains largely unknown, and the prognosis varies.4,5 There may be a family history, as there appears to be a genetic component to this disease. The disorder may also occur in the absence of external stressors.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Young children often develop trichotillomania that is transient in nature and most often does not require formal intervention. Older children may benefit from psychotherapy.5

Clomipramine (Anafranil) has been shown to be more effective than placebo.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are no more effective than placebo.6,7 Pimozide (Orap), haloperidol (Haldol), and other agents have been reported to be of benefit in some instances. Although no large randomized clinical trials in children have been performed, N-acetylcysteine (Acetadote) seems to be a very promising form of therapy in adults.8 A multidisciplinary approach is usually helpful in finding the best treatment option for a particular patient.

- Shah KN, Fried RG. Factitial dermatoses in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18:403–409.

- Hautmann G, Hercogova J, Lotti T. Trichotillomania. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46:807–821.

- Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2003; 19:343–347.

- Franklin ME, Tolin DF, editors. In: Treating Trichotillomania: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Hairpulling and Related Problems. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

- Duke DC, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Trichotillomania: a current review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:181–193.

- Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Dombrowski P, et al. Systematic review: pharmacological and behavioral treatment for trichotillomania. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:839–846.

- Bloch MH. Trichotillomania across the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:879–883.

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:756–763.

A 12-year-old girl has a large, irregular area of hair loss over the central frontoparietal scalp. Physical examination reveals scattered short hairs of varying lengths and a few small crusts throughout the area of alopecia (Figure 1). The remainder of the scalp appears normal.

Q: Which diagnosis is most likely?

- Alopecia areata

- Lichen planopilaris

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Trichotillomania

- Follicular degeneration syndrome

A: The correct answer is trichotillomania, the compulsive pulling out of one’s own hair. Irregularly shaped areas of alopecia containing short hairs of varied lengths and excoriation should raise clinical suspicion of trichotillomania. Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis when follicles devoid of hair shafts, hemorrhage, and misshapen fragments of scalp hair (pigment casts) are seen.

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Trichotillomania may present as striking hair loss (alopecia) with an irregular pattern, often with sharp angles or scalloped borders.1 Short and broken hairs within involved areas are typically seen because regenerating hairs are too short to be grasped and pulled out.2 Although hair loss on the scalp may be most evident, hair loss on any hair-bearing area of the body may be noted, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Family members and the affected individual are often aware of compulsive manipulation of hair.

Depression, anxiety, and other grooming behaviors such as skin-picking and nail-biting may be associated with trichotillomania. Affected individuals often feel a sense of gratification from pulling out hairs. Although systemic complications are rare, some individuals ingest the removed hairs (trichophagy), and the hairs may be caught in the gastric folds and eventually form a trichobezoar.3

The diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings and by asking the patient about hair-pulling. Asking the patient if the habit is due to the feel of the hair, a need to calm himself or herself, or other factors may be revealing. The majority of cases can be diagnosed without biopsy. Biopsy from affected areas reveals changes related to trauma such as empty hair follicles, hemorrhage, and hair shaft fragments in the dermis2 (Figure 2). The number of catagen follicles is increased. Other causes of patchy alopecia are associated with different findings on biopsy.

Alopecia areata may be associated with an increased number of catagen hairs but is characterized by a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate.

Biopsy of lichen planopilaris typically reveals vacuolar changes along the dermal-follicular junction and necrotic keratinocytes.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is associated with thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased mucin in the dermis, follicular plugging by keratin, and vacuolar changes along the dermal-epidermal junction.

Biopsy of follicular degeneration syndrome exhibits premature desquamation of the internal root sheath as well as an increased number of fibrous tracts marking the sites of lost hairs.

The etiology of trichotillomania remains largely unknown, and the prognosis varies.4,5 There may be a family history, as there appears to be a genetic component to this disease. The disorder may also occur in the absence of external stressors.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Young children often develop trichotillomania that is transient in nature and most often does not require formal intervention. Older children may benefit from psychotherapy.5

Clomipramine (Anafranil) has been shown to be more effective than placebo.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are no more effective than placebo.6,7 Pimozide (Orap), haloperidol (Haldol), and other agents have been reported to be of benefit in some instances. Although no large randomized clinical trials in children have been performed, N-acetylcysteine (Acetadote) seems to be a very promising form of therapy in adults.8 A multidisciplinary approach is usually helpful in finding the best treatment option for a particular patient.

A 12-year-old girl has a large, irregular area of hair loss over the central frontoparietal scalp. Physical examination reveals scattered short hairs of varying lengths and a few small crusts throughout the area of alopecia (Figure 1). The remainder of the scalp appears normal.

Q: Which diagnosis is most likely?

- Alopecia areata

- Lichen planopilaris

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Trichotillomania

- Follicular degeneration syndrome

A: The correct answer is trichotillomania, the compulsive pulling out of one’s own hair. Irregularly shaped areas of alopecia containing short hairs of varied lengths and excoriation should raise clinical suspicion of trichotillomania. Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis when follicles devoid of hair shafts, hemorrhage, and misshapen fragments of scalp hair (pigment casts) are seen.

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

Trichotillomania may present as striking hair loss (alopecia) with an irregular pattern, often with sharp angles or scalloped borders.1 Short and broken hairs within involved areas are typically seen because regenerating hairs are too short to be grasped and pulled out.2 Although hair loss on the scalp may be most evident, hair loss on any hair-bearing area of the body may be noted, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Family members and the affected individual are often aware of compulsive manipulation of hair.

Depression, anxiety, and other grooming behaviors such as skin-picking and nail-biting may be associated with trichotillomania. Affected individuals often feel a sense of gratification from pulling out hairs. Although systemic complications are rare, some individuals ingest the removed hairs (trichophagy), and the hairs may be caught in the gastric folds and eventually form a trichobezoar.3

The diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings and by asking the patient about hair-pulling. Asking the patient if the habit is due to the feel of the hair, a need to calm himself or herself, or other factors may be revealing. The majority of cases can be diagnosed without biopsy. Biopsy from affected areas reveals changes related to trauma such as empty hair follicles, hemorrhage, and hair shaft fragments in the dermis2 (Figure 2). The number of catagen follicles is increased. Other causes of patchy alopecia are associated with different findings on biopsy.

Alopecia areata may be associated with an increased number of catagen hairs but is characterized by a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate.

Biopsy of lichen planopilaris typically reveals vacuolar changes along the dermal-follicular junction and necrotic keratinocytes.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is associated with thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased mucin in the dermis, follicular plugging by keratin, and vacuolar changes along the dermal-epidermal junction.

Biopsy of follicular degeneration syndrome exhibits premature desquamation of the internal root sheath as well as an increased number of fibrous tracts marking the sites of lost hairs.

The etiology of trichotillomania remains largely unknown, and the prognosis varies.4,5 There may be a family history, as there appears to be a genetic component to this disease. The disorder may also occur in the absence of external stressors.5

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Young children often develop trichotillomania that is transient in nature and most often does not require formal intervention. Older children may benefit from psychotherapy.5

Clomipramine (Anafranil) has been shown to be more effective than placebo.6 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are no more effective than placebo.6,7 Pimozide (Orap), haloperidol (Haldol), and other agents have been reported to be of benefit in some instances. Although no large randomized clinical trials in children have been performed, N-acetylcysteine (Acetadote) seems to be a very promising form of therapy in adults.8 A multidisciplinary approach is usually helpful in finding the best treatment option for a particular patient.

- Shah KN, Fried RG. Factitial dermatoses in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18:403–409.

- Hautmann G, Hercogova J, Lotti T. Trichotillomania. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46:807–821.

- Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2003; 19:343–347.

- Franklin ME, Tolin DF, editors. In: Treating Trichotillomania: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Hairpulling and Related Problems. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

- Duke DC, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Trichotillomania: a current review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:181–193.

- Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Dombrowski P, et al. Systematic review: pharmacological and behavioral treatment for trichotillomania. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:839–846.

- Bloch MH. Trichotillomania across the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:879–883.

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:756–763.

- Shah KN, Fried RG. Factitial dermatoses in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18:403–409.

- Hautmann G, Hercogova J, Lotti T. Trichotillomania. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46:807–821.

- Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2003; 19:343–347.

- Franklin ME, Tolin DF, editors. In: Treating Trichotillomania: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Hairpulling and Related Problems. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

- Duke DC, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Trichotillomania: a current review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:181–193.

- Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Dombrowski P, et al. Systematic review: pharmacological and behavioral treatment for trichotillomania. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:839–846.

- Bloch MH. Trichotillomania across the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:879–883.

- Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:756–763.