User login

What is the best surgical therapy for the secondary prevention of stroke?

Case

A 62-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and a pack-a-day smoking habit presents to the emergency department for acute onset of left-side arm and leg weakness and sensory loss on awakening.

She reports taking a baby aspirin daily to “prevent heart attacks.” Her electrocardiogram demonstrates a left bundle branch block and frequent premature atrial contractions. She recovers partially but has residual mild hemiparesis. A duplex carotid ultrasound shows 80% stenosis of the right internal carotid artery.

Overview

In the United States each year approximately 700,000 cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) constitute the largest cause of age-adjusted morbidity of any illness.1 About 200,000 of these strokes are recurrent events.

CVA is the third-leading cause of death. Hospitalists increasingly are responsible for the inpatient care of patients with acute CVA. Atheroembolism from carotid atherosclerosis is the suspected cause for about one in five ischemic strokes.2

The link between carotid stenosis and stroke has been recognized for many years. The first carotid endarterectomy (CEA) was reported more than 50 years ago.3

This targeted review covers the natural history of symptomatic carotid stenosis, the key efficacy trials of CEA and carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) among symptomatic patients, and pitfalls for properly diagnosing the severity of carotid stenosis. The medical therapy of carotid stenosis and the secondary prevention of CVA were recently reviewed in The Hospitalist (October 2007, p. 34).

Natural History

The presence or absence of referable neurological symptoms is pivotal to understanding the near-term risk for recurrent CVA related to carotid stenosis. In the absence of symptoms, the risk for future CVA is essentially constant over years.

However, once symptoms occur, the risk for a second event accelerates substantially. Among patients with newly symptomatic carotid stenosis, the risk for another transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke within the following 24 months is 26%.4 This risk peaks within the first month or two following the index event, underscoring the time-dependent nature of carotid evaluation and intervention.

Guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology on the management of ischemic stroke assign early carotid intervention, defined as within two weeks from the index event, a Class 2 indication.5 Hospitalists must rapidly identify the severity of carotid stenosis and make timely referrals to meet this recommended therapeutic window.

Carotid Endarterectomy

CEA is perhaps the best-studied surgical procedure, with multiple well-conducted prospective randomized trials demonstrating its efficacy. The procedure had been performed for hundreds of thousands of patients prior to this data being published in the early 1990s. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) was the landmark study demonstrating the efficacy of intervention. The trial of patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis was stopped early for patients with severe stenosis, defined as 70% to 99% narrowing by conventional angiography. At two years, the rate of ipsilateral stroke or post-operative death in patients with severe stenosis decreased from 26% in the medical arm to 9% in the CEA arm [an absolute risk reduction of 17% and number needed to treat of six (p<0.001)].

Rarely has any medical or surgical procedure had such a robust effect over so short an interval for such an important outcome. Patients with less severe stenosis were followed out to five years, with the final results showing benefit among patients with moderate stenosis (50% to 69%).6 The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Trial 309 and the European Carotid Stenosis Trial (ECST) were combined with NASCET in a pooled analysis of more than 6,000 patients and about 35,000 patient-years of follow-up.7-9

Among patients with 70% or greater stenosis, CEA reduced the absolute five-year risk of ipsilateral ischemic stroke and any operative stroke or death by 16% (95% confidence interval 11.2% to 20.8%). The benefit was less pronounced among patients with 50% to 69% stenosis, in whom CEA conferred a 4.6% (95% confidence interval 0.6% to 8.6%) absolute five-year risk reduction.

The medical aspect of these trials required only the use of aspirin. Intensive lipid control and tight glycemic and blood pressure control would probably reduce the rate of events. The 30-day operative risk was consistently less than 6% across these trials, with the benefit seen by two years among patients with 70% to 99% stenosis and by five years among patients with 50% to 69% stenosis.

Referring hospitalists should know the operative event rates of the surgeons to whom they are referring. Hospitalists should also refer those patients whose anticipated life expectancy is at least two years for patients with 70% to 99% stenosis and at least five years for patients with 50% to 69% stenosis.

Carotid Angioplasty and Stenting

CAS is increasingly used as an alternative to CEA among selected patients. Two procedural developments have improved the safety of percutaneous carotid revascularization.

First, distal embolic protection filters deployed prior to angioplasty collect debris associated with the mechanical intervention and limit the risk of peri-procedural stroke. (See Figures 1 and 2, p. 36.)

Second, the use of self-expanding stents has improved long-term patency over balloon-expanding stents, which can be damaged by neck movement and external pressure.

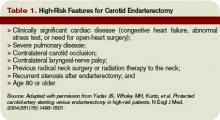

The Stenting and Angioplasty with [distal embolic] Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy trial demonstrated the noninferiority of CAS versus CEA among high-risk patients.10 Inclusion criteria were symptomatic carotid stenosis of greater than 50% or asymptomatic stenosis greater than 80%. Patients had to have one of several high-risk features to be included. (See Table 1, above)

The cumulative incidence of post-operative stroke, myocardial infarction, death, and ipsilateral stroke within one year after the procedure was 20.1% in the CEA arm and 12.2% in the CAS arm (p=0.004 for noninferiority and p=0.053 for superiority). The rate of post-procedural cranial nerve injury was substantially lower (zero) in the CEA arm.

However, among those patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis, the cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint was 16.8% in the CAS arm and 16.5% in the CEA arm. Based upon this trial, CAS has equivalent one-year outcomes versus CEA in a high-risk population.

The Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study trial was the first large prospective trial comparing CEA and CAS among symptomatic patients with severe carotid stenosis (mean 86.4% stenosis).11 At 30 days, the rate of death or disabling stroke was 6.4% with CAS and 5.9% with CEA, which were not significantly different in this trial of about 500 patients.

The trial was begun in 1994, with a large portion of angioplasty performed without stents or distal embolic protection. There were fewer local complications but higher rates of restenosis in the CAS arm. The authors noted “no substantial difference in the rate of ipsilateral stroke … up to three years after randomization” but cautioned that the confidence intervals were wide.

Two recently published trials of CAS versus CEA in lower-risk populations do not support the overall safety of CAS among symptomatic patients. The Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy trial randomized 1,200 average-risk patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis of 50% or greater by angiography or 70% of greater by ultrasound to either CAS or CEA.12

The trial design stipulated that both surgeons and percutaneous interventionalists perform at least 25 procedures prior to inclusion in the study and that independent quality committees review these procedures. The use of distal embolic protection devices was left to the discretion of the operators. The 30-day rate of death or ipsilateral ischemic stroke was 6.34% in the CEA arm and 6.84% in the CAS arm (p=0.09 for noninferiority).

The investigators concluded that CAS is not non-inferior to CEA (i.e., that CAS is inferior). The Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis trial randomized 527 patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis of 70% or greater by angiography or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) to either CAS or CEA within two weeks of the index event.13

This trial design also stipulated that surgeons had performed at least 25 CEAs in the prior year. Percutaneous interventionalists did not have similar numeric procedure requirements, although the investigators provided for tutoring of less experienced operators. The trial was stopped prematurely due to futility (in terms of noninferiority) and harm within the CAS arm.

The 30-day cumulative incidence of death or any stroke was 3.9% in the CEA arm and 9.6% in the CAS arm (p=0.01 for superiority of CEA). The trial was powered to detect only large differences among low- and high-volume operators. Nearly 10% of patients did not have distal embolic protection devices used during their CAS procedures. Ongoing trials will further define the role of CAS versus CEA in the interventional treatment of carotid stenosis.

Accurate Diagnosis

Different trials used different criteria for defining the percent stenosis of the diseased carotid arterial segment. These differences were based primarily on the mode of testing (i.e., conventional angiography versus ultrasound), and on what portion of the carotid artery was used as the reference or baseline segment to calculate the percent stenosis.

A meta-analysis of various non-invasive modes of testing for carotid stenosis concluded that duplex ultrasound had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 87%, respectively, to distinguish 70% to 99% stenosis from less than 70% stenosis.14 MRA had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 95% and 90%, respectively.

The authors selected trials comparing these non-invasive methods with the gold standard of digital subtraction angiography. Using ultrasonography to first identify patients with at least 50% stenosis, followed by MRA or conventional angiography to more accurately confirm the degree of stenosis has been shown to be cost-effective.15

Back to the Case

For the patient in the vignette, the positive ultrasonography should lead to an MRA or conventional angiography to more precisely determine the percent stenosis. Current guidelines would suggest referring the patient for CEA to be completed within the next two weeks to treat a 50% or greater stenosis. That’s provided the surgeons have an operative morbidity and mortality rate less than 6% and her life expectancy is at least five years. If the patient had high-risk features as listed in Table 1 (left), referral for CAS in the hands of an experienced operator would be an alternative. TH

Dr. Anderson is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, and an associate program director of the internal medicine residency program.

References

- Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69-e171.

- White H, Boden-Albala B, Wang C, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype incidence among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1327-1331.

- Eastcott HH, Pickering GW, Rob CG. Reconstruction of internal carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia. Lancet. 1954;267(6846):994-996.

- Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis: North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325(7):445-453.

- Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; American Academy of Neurology. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Circulation. 2006;113:e409-e449.

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists’ Collaborative Group. The final results of the NASCET trial. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1415-1425.

- Mayberg MR, Wilson E, Yatsu F, et al. Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis. JAMA. 1991;266:3289-3294.

- European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Investigators. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet. 1998;351:1379-1387.

- Rothwell P, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov A, et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):107-116.

- Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz, et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1493-1501.

- Endovascular versus surgical treatment in patients with carotid stenosis in the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1729-1737.

- SPACE Collaborative Group. 30-day results from the SPACE trial of stent-protected angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients: a randomised noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1239-1247.

- Mas J, Chatellier G, Beyssen B, et al. EVA-3S Investigators. Endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1660-1671.

- Nederkoorn PJ, van der Graaf Y, Hunink MG. Duplex ultrasound and magnetic resonance angiography compared with digital subtraction angiography in carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34:1324-1332.

- U-King-Im JM, Hollingworth W, Trivedi RA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies prior to carotid endarterectomy. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(4):506-515.

Case

A 62-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and a pack-a-day smoking habit presents to the emergency department for acute onset of left-side arm and leg weakness and sensory loss on awakening.

She reports taking a baby aspirin daily to “prevent heart attacks.” Her electrocardiogram demonstrates a left bundle branch block and frequent premature atrial contractions. She recovers partially but has residual mild hemiparesis. A duplex carotid ultrasound shows 80% stenosis of the right internal carotid artery.

Overview

In the United States each year approximately 700,000 cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) constitute the largest cause of age-adjusted morbidity of any illness.1 About 200,000 of these strokes are recurrent events.

CVA is the third-leading cause of death. Hospitalists increasingly are responsible for the inpatient care of patients with acute CVA. Atheroembolism from carotid atherosclerosis is the suspected cause for about one in five ischemic strokes.2

The link between carotid stenosis and stroke has been recognized for many years. The first carotid endarterectomy (CEA) was reported more than 50 years ago.3

This targeted review covers the natural history of symptomatic carotid stenosis, the key efficacy trials of CEA and carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) among symptomatic patients, and pitfalls for properly diagnosing the severity of carotid stenosis. The medical therapy of carotid stenosis and the secondary prevention of CVA were recently reviewed in The Hospitalist (October 2007, p. 34).

Natural History

The presence or absence of referable neurological symptoms is pivotal to understanding the near-term risk for recurrent CVA related to carotid stenosis. In the absence of symptoms, the risk for future CVA is essentially constant over years.

However, once symptoms occur, the risk for a second event accelerates substantially. Among patients with newly symptomatic carotid stenosis, the risk for another transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke within the following 24 months is 26%.4 This risk peaks within the first month or two following the index event, underscoring the time-dependent nature of carotid evaluation and intervention.

Guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology on the management of ischemic stroke assign early carotid intervention, defined as within two weeks from the index event, a Class 2 indication.5 Hospitalists must rapidly identify the severity of carotid stenosis and make timely referrals to meet this recommended therapeutic window.

Carotid Endarterectomy

CEA is perhaps the best-studied surgical procedure, with multiple well-conducted prospective randomized trials demonstrating its efficacy. The procedure had been performed for hundreds of thousands of patients prior to this data being published in the early 1990s. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) was the landmark study demonstrating the efficacy of intervention. The trial of patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis was stopped early for patients with severe stenosis, defined as 70% to 99% narrowing by conventional angiography. At two years, the rate of ipsilateral stroke or post-operative death in patients with severe stenosis decreased from 26% in the medical arm to 9% in the CEA arm [an absolute risk reduction of 17% and number needed to treat of six (p<0.001)].

Rarely has any medical or surgical procedure had such a robust effect over so short an interval for such an important outcome. Patients with less severe stenosis were followed out to five years, with the final results showing benefit among patients with moderate stenosis (50% to 69%).6 The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Trial 309 and the European Carotid Stenosis Trial (ECST) were combined with NASCET in a pooled analysis of more than 6,000 patients and about 35,000 patient-years of follow-up.7-9

Among patients with 70% or greater stenosis, CEA reduced the absolute five-year risk of ipsilateral ischemic stroke and any operative stroke or death by 16% (95% confidence interval 11.2% to 20.8%). The benefit was less pronounced among patients with 50% to 69% stenosis, in whom CEA conferred a 4.6% (95% confidence interval 0.6% to 8.6%) absolute five-year risk reduction.

The medical aspect of these trials required only the use of aspirin. Intensive lipid control and tight glycemic and blood pressure control would probably reduce the rate of events. The 30-day operative risk was consistently less than 6% across these trials, with the benefit seen by two years among patients with 70% to 99% stenosis and by five years among patients with 50% to 69% stenosis.

Referring hospitalists should know the operative event rates of the surgeons to whom they are referring. Hospitalists should also refer those patients whose anticipated life expectancy is at least two years for patients with 70% to 99% stenosis and at least five years for patients with 50% to 69% stenosis.

Carotid Angioplasty and Stenting

CAS is increasingly used as an alternative to CEA among selected patients. Two procedural developments have improved the safety of percutaneous carotid revascularization.

First, distal embolic protection filters deployed prior to angioplasty collect debris associated with the mechanical intervention and limit the risk of peri-procedural stroke. (See Figures 1 and 2, p. 36.)

Second, the use of self-expanding stents has improved long-term patency over balloon-expanding stents, which can be damaged by neck movement and external pressure.

The Stenting and Angioplasty with [distal embolic] Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy trial demonstrated the noninferiority of CAS versus CEA among high-risk patients.10 Inclusion criteria were symptomatic carotid stenosis of greater than 50% or asymptomatic stenosis greater than 80%. Patients had to have one of several high-risk features to be included. (See Table 1, above)

The cumulative incidence of post-operative stroke, myocardial infarction, death, and ipsilateral stroke within one year after the procedure was 20.1% in the CEA arm and 12.2% in the CAS arm (p=0.004 for noninferiority and p=0.053 for superiority). The rate of post-procedural cranial nerve injury was substantially lower (zero) in the CEA arm.

However, among those patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis, the cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint was 16.8% in the CAS arm and 16.5% in the CEA arm. Based upon this trial, CAS has equivalent one-year outcomes versus CEA in a high-risk population.

The Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study trial was the first large prospective trial comparing CEA and CAS among symptomatic patients with severe carotid stenosis (mean 86.4% stenosis).11 At 30 days, the rate of death or disabling stroke was 6.4% with CAS and 5.9% with CEA, which were not significantly different in this trial of about 500 patients.

The trial was begun in 1994, with a large portion of angioplasty performed without stents or distal embolic protection. There were fewer local complications but higher rates of restenosis in the CAS arm. The authors noted “no substantial difference in the rate of ipsilateral stroke … up to three years after randomization” but cautioned that the confidence intervals were wide.

Two recently published trials of CAS versus CEA in lower-risk populations do not support the overall safety of CAS among symptomatic patients. The Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy trial randomized 1,200 average-risk patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis of 50% or greater by angiography or 70% of greater by ultrasound to either CAS or CEA.12

The trial design stipulated that both surgeons and percutaneous interventionalists perform at least 25 procedures prior to inclusion in the study and that independent quality committees review these procedures. The use of distal embolic protection devices was left to the discretion of the operators. The 30-day rate of death or ipsilateral ischemic stroke was 6.34% in the CEA arm and 6.84% in the CAS arm (p=0.09 for noninferiority).

The investigators concluded that CAS is not non-inferior to CEA (i.e., that CAS is inferior). The Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis trial randomized 527 patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis of 70% or greater by angiography or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) to either CAS or CEA within two weeks of the index event.13

This trial design also stipulated that surgeons had performed at least 25 CEAs in the prior year. Percutaneous interventionalists did not have similar numeric procedure requirements, although the investigators provided for tutoring of less experienced operators. The trial was stopped prematurely due to futility (in terms of noninferiority) and harm within the CAS arm.

The 30-day cumulative incidence of death or any stroke was 3.9% in the CEA arm and 9.6% in the CAS arm (p=0.01 for superiority of CEA). The trial was powered to detect only large differences among low- and high-volume operators. Nearly 10% of patients did not have distal embolic protection devices used during their CAS procedures. Ongoing trials will further define the role of CAS versus CEA in the interventional treatment of carotid stenosis.

Accurate Diagnosis

Different trials used different criteria for defining the percent stenosis of the diseased carotid arterial segment. These differences were based primarily on the mode of testing (i.e., conventional angiography versus ultrasound), and on what portion of the carotid artery was used as the reference or baseline segment to calculate the percent stenosis.

A meta-analysis of various non-invasive modes of testing for carotid stenosis concluded that duplex ultrasound had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 87%, respectively, to distinguish 70% to 99% stenosis from less than 70% stenosis.14 MRA had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 95% and 90%, respectively.

The authors selected trials comparing these non-invasive methods with the gold standard of digital subtraction angiography. Using ultrasonography to first identify patients with at least 50% stenosis, followed by MRA or conventional angiography to more accurately confirm the degree of stenosis has been shown to be cost-effective.15

Back to the Case

For the patient in the vignette, the positive ultrasonography should lead to an MRA or conventional angiography to more precisely determine the percent stenosis. Current guidelines would suggest referring the patient for CEA to be completed within the next two weeks to treat a 50% or greater stenosis. That’s provided the surgeons have an operative morbidity and mortality rate less than 6% and her life expectancy is at least five years. If the patient had high-risk features as listed in Table 1 (left), referral for CAS in the hands of an experienced operator would be an alternative. TH

Dr. Anderson is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, and an associate program director of the internal medicine residency program.

References

- Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69-e171.

- White H, Boden-Albala B, Wang C, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype incidence among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1327-1331.

- Eastcott HH, Pickering GW, Rob CG. Reconstruction of internal carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia. Lancet. 1954;267(6846):994-996.

- Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis: North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325(7):445-453.

- Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; American Academy of Neurology. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Circulation. 2006;113:e409-e449.

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists’ Collaborative Group. The final results of the NASCET trial. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1415-1425.

- Mayberg MR, Wilson E, Yatsu F, et al. Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis. JAMA. 1991;266:3289-3294.

- European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Investigators. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet. 1998;351:1379-1387.

- Rothwell P, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov A, et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):107-116.

- Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz, et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1493-1501.

- Endovascular versus surgical treatment in patients with carotid stenosis in the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1729-1737.

- SPACE Collaborative Group. 30-day results from the SPACE trial of stent-protected angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients: a randomised noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1239-1247.

- Mas J, Chatellier G, Beyssen B, et al. EVA-3S Investigators. Endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1660-1671.

- Nederkoorn PJ, van der Graaf Y, Hunink MG. Duplex ultrasound and magnetic resonance angiography compared with digital subtraction angiography in carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34:1324-1332.

- U-King-Im JM, Hollingworth W, Trivedi RA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies prior to carotid endarterectomy. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(4):506-515.

Case

A 62-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and a pack-a-day smoking habit presents to the emergency department for acute onset of left-side arm and leg weakness and sensory loss on awakening.

She reports taking a baby aspirin daily to “prevent heart attacks.” Her electrocardiogram demonstrates a left bundle branch block and frequent premature atrial contractions. She recovers partially but has residual mild hemiparesis. A duplex carotid ultrasound shows 80% stenosis of the right internal carotid artery.

Overview

In the United States each year approximately 700,000 cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) constitute the largest cause of age-adjusted morbidity of any illness.1 About 200,000 of these strokes are recurrent events.

CVA is the third-leading cause of death. Hospitalists increasingly are responsible for the inpatient care of patients with acute CVA. Atheroembolism from carotid atherosclerosis is the suspected cause for about one in five ischemic strokes.2

The link between carotid stenosis and stroke has been recognized for many years. The first carotid endarterectomy (CEA) was reported more than 50 years ago.3

This targeted review covers the natural history of symptomatic carotid stenosis, the key efficacy trials of CEA and carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) among symptomatic patients, and pitfalls for properly diagnosing the severity of carotid stenosis. The medical therapy of carotid stenosis and the secondary prevention of CVA were recently reviewed in The Hospitalist (October 2007, p. 34).

Natural History

The presence or absence of referable neurological symptoms is pivotal to understanding the near-term risk for recurrent CVA related to carotid stenosis. In the absence of symptoms, the risk for future CVA is essentially constant over years.

However, once symptoms occur, the risk for a second event accelerates substantially. Among patients with newly symptomatic carotid stenosis, the risk for another transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke within the following 24 months is 26%.4 This risk peaks within the first month or two following the index event, underscoring the time-dependent nature of carotid evaluation and intervention.

Guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology on the management of ischemic stroke assign early carotid intervention, defined as within two weeks from the index event, a Class 2 indication.5 Hospitalists must rapidly identify the severity of carotid stenosis and make timely referrals to meet this recommended therapeutic window.

Carotid Endarterectomy

CEA is perhaps the best-studied surgical procedure, with multiple well-conducted prospective randomized trials demonstrating its efficacy. The procedure had been performed for hundreds of thousands of patients prior to this data being published in the early 1990s. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) was the landmark study demonstrating the efficacy of intervention. The trial of patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis was stopped early for patients with severe stenosis, defined as 70% to 99% narrowing by conventional angiography. At two years, the rate of ipsilateral stroke or post-operative death in patients with severe stenosis decreased from 26% in the medical arm to 9% in the CEA arm [an absolute risk reduction of 17% and number needed to treat of six (p<0.001)].

Rarely has any medical or surgical procedure had such a robust effect over so short an interval for such an important outcome. Patients with less severe stenosis were followed out to five years, with the final results showing benefit among patients with moderate stenosis (50% to 69%).6 The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Trial 309 and the European Carotid Stenosis Trial (ECST) were combined with NASCET in a pooled analysis of more than 6,000 patients and about 35,000 patient-years of follow-up.7-9

Among patients with 70% or greater stenosis, CEA reduced the absolute five-year risk of ipsilateral ischemic stroke and any operative stroke or death by 16% (95% confidence interval 11.2% to 20.8%). The benefit was less pronounced among patients with 50% to 69% stenosis, in whom CEA conferred a 4.6% (95% confidence interval 0.6% to 8.6%) absolute five-year risk reduction.

The medical aspect of these trials required only the use of aspirin. Intensive lipid control and tight glycemic and blood pressure control would probably reduce the rate of events. The 30-day operative risk was consistently less than 6% across these trials, with the benefit seen by two years among patients with 70% to 99% stenosis and by five years among patients with 50% to 69% stenosis.

Referring hospitalists should know the operative event rates of the surgeons to whom they are referring. Hospitalists should also refer those patients whose anticipated life expectancy is at least two years for patients with 70% to 99% stenosis and at least five years for patients with 50% to 69% stenosis.

Carotid Angioplasty and Stenting

CAS is increasingly used as an alternative to CEA among selected patients. Two procedural developments have improved the safety of percutaneous carotid revascularization.

First, distal embolic protection filters deployed prior to angioplasty collect debris associated with the mechanical intervention and limit the risk of peri-procedural stroke. (See Figures 1 and 2, p. 36.)

Second, the use of self-expanding stents has improved long-term patency over balloon-expanding stents, which can be damaged by neck movement and external pressure.

The Stenting and Angioplasty with [distal embolic] Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy trial demonstrated the noninferiority of CAS versus CEA among high-risk patients.10 Inclusion criteria were symptomatic carotid stenosis of greater than 50% or asymptomatic stenosis greater than 80%. Patients had to have one of several high-risk features to be included. (See Table 1, above)

The cumulative incidence of post-operative stroke, myocardial infarction, death, and ipsilateral stroke within one year after the procedure was 20.1% in the CEA arm and 12.2% in the CAS arm (p=0.004 for noninferiority and p=0.053 for superiority). The rate of post-procedural cranial nerve injury was substantially lower (zero) in the CEA arm.

However, among those patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis, the cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint was 16.8% in the CAS arm and 16.5% in the CEA arm. Based upon this trial, CAS has equivalent one-year outcomes versus CEA in a high-risk population.

The Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study trial was the first large prospective trial comparing CEA and CAS among symptomatic patients with severe carotid stenosis (mean 86.4% stenosis).11 At 30 days, the rate of death or disabling stroke was 6.4% with CAS and 5.9% with CEA, which were not significantly different in this trial of about 500 patients.

The trial was begun in 1994, with a large portion of angioplasty performed without stents or distal embolic protection. There were fewer local complications but higher rates of restenosis in the CAS arm. The authors noted “no substantial difference in the rate of ipsilateral stroke … up to three years after randomization” but cautioned that the confidence intervals were wide.

Two recently published trials of CAS versus CEA in lower-risk populations do not support the overall safety of CAS among symptomatic patients. The Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy trial randomized 1,200 average-risk patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis of 50% or greater by angiography or 70% of greater by ultrasound to either CAS or CEA.12

The trial design stipulated that both surgeons and percutaneous interventionalists perform at least 25 procedures prior to inclusion in the study and that independent quality committees review these procedures. The use of distal embolic protection devices was left to the discretion of the operators. The 30-day rate of death or ipsilateral ischemic stroke was 6.34% in the CEA arm and 6.84% in the CAS arm (p=0.09 for noninferiority).

The investigators concluded that CAS is not non-inferior to CEA (i.e., that CAS is inferior). The Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis trial randomized 527 patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis of 70% or greater by angiography or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) to either CAS or CEA within two weeks of the index event.13

This trial design also stipulated that surgeons had performed at least 25 CEAs in the prior year. Percutaneous interventionalists did not have similar numeric procedure requirements, although the investigators provided for tutoring of less experienced operators. The trial was stopped prematurely due to futility (in terms of noninferiority) and harm within the CAS arm.

The 30-day cumulative incidence of death or any stroke was 3.9% in the CEA arm and 9.6% in the CAS arm (p=0.01 for superiority of CEA). The trial was powered to detect only large differences among low- and high-volume operators. Nearly 10% of patients did not have distal embolic protection devices used during their CAS procedures. Ongoing trials will further define the role of CAS versus CEA in the interventional treatment of carotid stenosis.

Accurate Diagnosis

Different trials used different criteria for defining the percent stenosis of the diseased carotid arterial segment. These differences were based primarily on the mode of testing (i.e., conventional angiography versus ultrasound), and on what portion of the carotid artery was used as the reference or baseline segment to calculate the percent stenosis.

A meta-analysis of various non-invasive modes of testing for carotid stenosis concluded that duplex ultrasound had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 87%, respectively, to distinguish 70% to 99% stenosis from less than 70% stenosis.14 MRA had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 95% and 90%, respectively.

The authors selected trials comparing these non-invasive methods with the gold standard of digital subtraction angiography. Using ultrasonography to first identify patients with at least 50% stenosis, followed by MRA or conventional angiography to more accurately confirm the degree of stenosis has been shown to be cost-effective.15

Back to the Case

For the patient in the vignette, the positive ultrasonography should lead to an MRA or conventional angiography to more precisely determine the percent stenosis. Current guidelines would suggest referring the patient for CEA to be completed within the next two weeks to treat a 50% or greater stenosis. That’s provided the surgeons have an operative morbidity and mortality rate less than 6% and her life expectancy is at least five years. If the patient had high-risk features as listed in Table 1 (left), referral for CAS in the hands of an experienced operator would be an alternative. TH

Dr. Anderson is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, and an associate program director of the internal medicine residency program.

References

- Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69-e171.

- White H, Boden-Albala B, Wang C, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype incidence among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1327-1331.

- Eastcott HH, Pickering GW, Rob CG. Reconstruction of internal carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia. Lancet. 1954;267(6846):994-996.

- Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis: North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325(7):445-453.

- Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; American Academy of Neurology. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Circulation. 2006;113:e409-e449.

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists’ Collaborative Group. The final results of the NASCET trial. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1415-1425.

- Mayberg MR, Wilson E, Yatsu F, et al. Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis. JAMA. 1991;266:3289-3294.

- European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Investigators. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet. 1998;351:1379-1387.

- Rothwell P, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov A, et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):107-116.

- Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz, et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1493-1501.

- Endovascular versus surgical treatment in patients with carotid stenosis in the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1729-1737.

- SPACE Collaborative Group. 30-day results from the SPACE trial of stent-protected angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients: a randomised noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1239-1247.

- Mas J, Chatellier G, Beyssen B, et al. EVA-3S Investigators. Endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1660-1671.

- Nederkoorn PJ, van der Graaf Y, Hunink MG. Duplex ultrasound and magnetic resonance angiography compared with digital subtraction angiography in carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34:1324-1332.

- U-King-Im JM, Hollingworth W, Trivedi RA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies prior to carotid endarterectomy. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(4):506-515.