User login

Hormonal contraception and lactation: Reset your practices based on the evidence

CASE Patient concerned about hormonal contraception’s impact on lactation

A 19-year-old woman (G2P1102) is postpartum day 1 after delivering a baby at 26 weeks’ gestation. When you see her on postpartum rounds, she states that she does not want any hormonal contraception because she heard that it will decrease her milk supply. What are your next steps?

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently updated its policy statement on breastfeeding and the use of human milk to recommend exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and continued breastfeeding, with complementary foods, as mutually desired for 2 years or beyond given evidence of maternal health benefits with breastfeeding longer than 1 year.1

Breastfeeding prevalence—and challenges

Despite maternal and infant benefits associated with lactation, current breastfeeding prevalence in the United States remains suboptimal. In 2019, 24.9% of infants were exclusively breastfed through 6 months and 35.9% were breastfeeding at 12 months.2 Furthermore, disparities in breastfeeding exist, which contribute to health inequities. For example, non-Hispanic Black infants had lower rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months (19.1%) and any breastfeeding at 12 months (24.1%) compared with non-Hispanic White infants (26.9% and 39.4%, respectively).3

While many new mothers intend to breastfeed and initiate breastfeeding in the hospital after delivery, overall and exclusive breastfeeding continuation rates are low, indicating that patients face challenges with breastfeeding after hospital discharge. Many structural and societal barriers to breastfeeding exist, including inadequate social support and parental leave policies.4 Suboptimal maternity care practices during the birth hospitalization may lead to challenges with breastfeeding initiation. Health care practitioners may present additional barriers to breastfeeding due to a lack of knowledge of available resources for patients or incomplete training in breastfeeding counseling and support.

To address our case patient’s concerns, clinicians should be aware of how exogenous progestins may affect breastfeeding physiology, risk factors for breastfeeding difficulty, and the available evidence for safety of hormonal contraception use while breastfeeding.

Physiology of breastfeeding

During the second half of pregnancy, secretory differentiation (lactogenesis I) of mammary alveolar epithelial cells into secretory cells occurs to allow the mammary gland to eventually produce milk.5 After delivery of the placenta, progesterone withdrawal triggers secretory activation (lactogenesis II), which refers to the onset of copious milk production within 2 to 3 days postpartum.5 Most patients experience secretory activation within 72 hours; however, a delay in secretory activation past 72 hours is associated with cessation of any and exclusive breastfeeding at 4 weeks postpartum.6

Impaired lactation can be related to a delay in secretory activation or to insufficient lactation related to low milk supply. Maternal medical comorbidities (for example, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, obesity), breast anatomy (such as insufficient glandular tissue, prior breast reduction surgery), pregnancy-related events (preeclampsia, retained placenta, postpartum hemorrhage), and infant conditions (such as multiple gestation, premature birth, congenital anomalies) all contribute to a risk of impaired lactation.7

Guidance on breastfeeding and hormonal contraception initiation

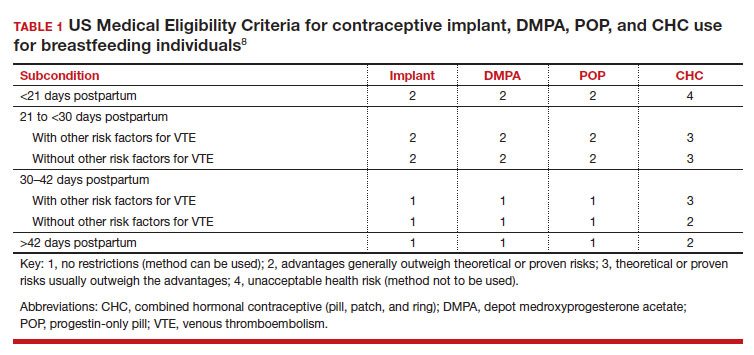

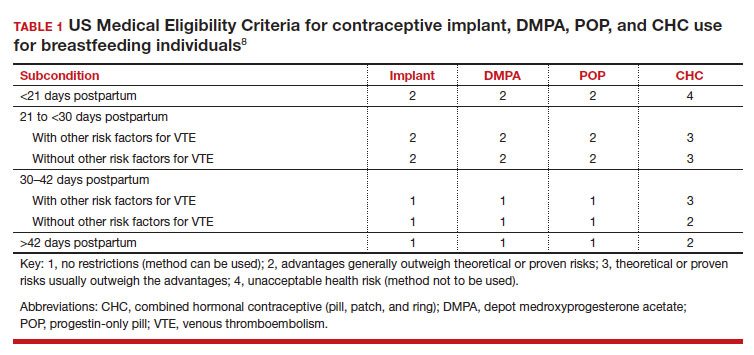

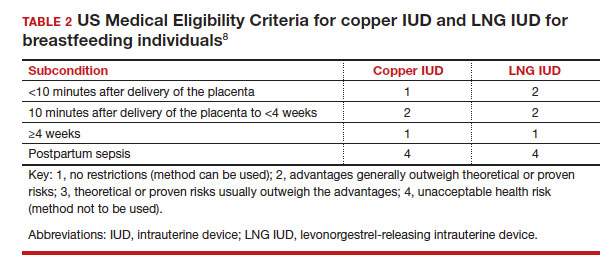

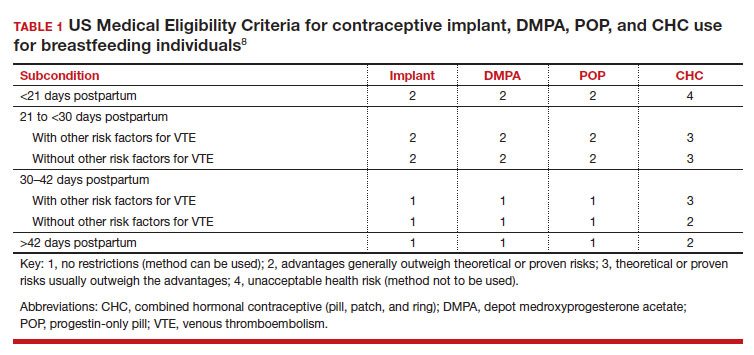

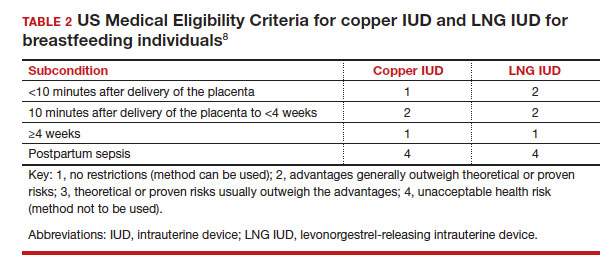

Early initiation of hormonal contraception poses theoretical concerns about breastfeeding difficulty if exogenous progestin interferes with endogenous signals for onset of milk production. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention US Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) for Contraceptive Use provide recommendations on the safety of contraceptive use in the setting of various medical conditions or patient characteristics based on available data. The MEC uses 4 categories in assessing the safety of contraceptive method use for individuals with specific medical conditions or characteristics: 1, no restrictions exist for use of the contraceptive method; 2, advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks; 3, theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages; and 4, conditions that represent an unacceptable health risk if the method is used.8

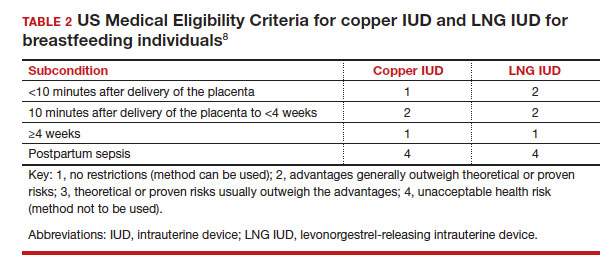

In the 2016 guidelines, combined hormonal contraceptives are considered category 4 at less than 21 days postpartum, regardless of breastfeeding status, due to the increased risk of venous thromboembolism in the immediate postpartum period (TABLE 1).8 Progestin-only contraception is considered category 1 in nonbreastfeeding individuals and category 2 in breastfeeding individuals based on overall evidence that found no adverse outcome with breastfeeding or infant outcomes with early initiation of progestin-only contraception (TABLE 1, TABLE 2).8

Since the publication of the 2016 MEC guidelines, several studies have continued to examine breastfeeding and infant outcomes with early initiation of hormonal contraception.

- In a noninferiority randomized controlled trial of immediate versus delayed initiation of a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG IUD), any breastfeeding at 8 weeks in the immediate group was 78% (95% confidence interval [CI], 70%–85%), which was lower than but within the specified noninferiority margin of the delayed breastfeeding group (83%; 95% CI, 75%–90%), indicating that breastfeeding outcomes with immediate initiation of an LNG IUD were not worse compared with delayed initiation.9

- A secondary analysis of a randomized trial that compared intracesarean versus LNG IUD placement at 6 or more weeks postpartum showed no difference in breastfeeding at 6, 12, and 24 weeks after LNG IUD placement.10

- A randomized trial of early (up to 48 hours postpartum) versus placement of an etonogestrel (ENG) implant at 6 or more weeks postpartum showed no difference between groups in infant weight at 12 months.11

- A randomized trial of immediate (within 5 days of delivery) or interval placement of the 2-rod LNG implant (not approved in the United States) showed no difference in change in infant weight from birth to 6 months after delivery, onset of secretory activation, or breastfeeding continuation at 3 and 6 months postpartum.12

- In a prospective cohort study that compared immediate postpartum initiation of ENG versus a 2-rod LNG implant (approved by the FDA but not marketed in the United States), there were no differences in breastfeeding continuation at 24 months and exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum.13

- In a noninferiority randomized controlled trial that compared ENG implant initiation in the delivery room (0–2 hours postdelivery) versus delayed initiation (24–48 hours postdelivery), the time to secretory activation in those who initiated an ENG implant in the delivery room (66.8 [SD, 25.2] hours) was noninferior to delayed initiation (66.0 [SD, 35.3] hours). There also was no difference in ongoing breastfeeding over the first year after delivery and implant use at 12 months.14

- A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial examined breastfeeding outcomes with receipt of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) prior to discharge in women who delivered infants who weighed 1,500 g or less at 32 weeks’ or less gestation. Time to secretory activation was longer in 29 women who received DMPA (103.7 hours) compared with 141 women who did not (88.6 hours; P = .028); however, there was no difference in daily milk production, lactation duration, or infant consumption of mother’s own milk.15

While the overall evidence suggests that early initiation of hormonal contraception does not affect breastfeeding or infant outcomes, it is important for clinicians to recognize the limitations of available data with regard to the populations included in these studies. Specifically, most studies did not include individuals with premature, low birth weight, or multiple gestation infants, who are at higher risk of impaired lactation, and individuals with a higher prevalence of breastfeeding were not included to determine whether early initiation of hormonal contraception would impact breastfeeding. Furthermore, while these studies enrolled participants who planned to breastfeed, data indicate that intentions to initiate and continue exclusive breastfeeding can vary.16 As the reported rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding are consistent with or lower than current US breastfeeding rates, any decrease in breastfeeding exclusivity or duration that may be attributable to hormonal contraception may be unacceptable to those who are strongly motivated to breastfeed.

Continue to: How can clinicians integrate evidence into contraception counseling?...

How can clinicians integrate evidence into contraception counseling?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine offer guidance for how clinicians can address the use of hormonal contraception in breastfeeding patients. Both organizations recommend discussing the risks and benefits of hormonal contraception within the context of each person’s desire to breastfeed, potential for breastfeeding difficulty, and risk of pregnancy so that individuals can make their own informed decisions.17,18

Obstetric care clinicians have an important role in helping patients make informed infant feeding decisions without coercion or pressure. To start these discussions, clinicians can begin by assessing a patient’s breastfeeding goals by asking open-ended questions, such as:

- What have you heard about breastfeeding?

- What are your plans for returning to work or school after delivery?

- How did breastfeeding go with older children?

- What are your plans for feeding this baby?

In addition to gathering information about the patient’s priorities and goals, clinicians should identify any risk factors for breastfeeding challenges in the medical, surgical, or previous breastfeeding history. Clinicians can engage in a patient-centered approach to infant feeding decisions by anticipating any challenges and working together to develop strategies to address these challenges with the patient’s goals in mind.17

When counseling about contraception, a spectrum of approaches exists, from a nondirective information-sharing only model to directive counseling by the clinician. The shared decision-making model lies between these 2 approaches and recognizes the expertise of both the clinician and patient.19 To start these interactions, clinicians can ask about a patient’s reproductive goals by assessing the patient’s needs, values, and preferences for contraception. Potential questions include:

- What kinds of contraceptive methods have you used in the past?

- What is important to you in a contraceptive method?

- How important is it to you to avoid another pregnancy right now?

Clinicians can then share information about different contraceptive methods based on the desired qualities that the patient has identified and how each method fits or does not fit into the patient’s goals and preferences. This collaborative approach facilitates an open dialogue and supports patient autonomy in contraceptive decision-making.

Lastly, clinicians should be cognizant of their own potential biases that could affect their counseling, such as encouraging contraceptive use because of a patient’s young age, parity, or premature delivery, as in our case presentation. Similarly, clinicians also should recognize that breastfeeding and contraceptive decisions are personal and are made with cultural, historical, and social contexts in mind.20 Ultimately, counseling should be patient centered and individualized for each person’s priorities related to infant feeding and pregnancy prevention. ●

- Meek JY, Noble L; Section on Breastfeeding. Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2022;150:e2022057988.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding report card, United States 2022. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2022-Breast feeding-Report-Card-H.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding by sociodemographic characteristic among children born in 2019. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/data-files/2019/rates-any-exclusive-bf-socio-dem-2019.html

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 821: barriers to breastfeeding: supporting initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e54-e62.

- Pang WW, Hartmann PE. Initiation of human lactation: secretory differentiation and secretory activation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12:211-221.

- Brownell E, Howard CR, Lawrence RA, et al. Delayed onset lactogenesis II predicts the cessation of any or exclusive breastfeeding. J Pediatr. 2012;161:608-614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 820: breastfeeding challenges. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e42-e53.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(RR-3):1-104.

- Turok DK, Leeman L, Sanders JN, et al. Immediate postpartum levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding outcomes: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:665.e1-665.e8.

- Levi EE, Findley MK, Avila K, et al. Placement of levonorgestrel intrauterine device at the time of cesarean delivery and the effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13:674-679.

- Carmo LSMP, Braga GC, Ferriani RA, et al. Timing of etonogestrel-releasing implants and growth of breastfed infants: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:100-107.

- Averbach S, Kakaire O, McDiehl R, et al. The effect of immediate postpartum levonorgestrel contraceptive implant use on breastfeeding and infant growth: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2019;99:87-93.

- Krashin JW, Lemani C, Nkambule J, et al. A comparison of breastfeeding exclusivity and duration rates between immediate postpartum levonorgestrel versus etonogestrel implant users: a prospective cohort study. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14:69-76.

- Henkel A, Lerma K, Reyes G, et al. Lactogenesis and breastfeeding after immediate vs delayed birth-hospitalization insertion of etonogestrel contraceptive implant: a noninferiority trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023; 228:55.e1-55.e9.

- Parker LA, Sullivan S, Cacho N, et al. Effect of postpartum depo medroxyprogesterone acetate on lactation in mothers of very low-birth-weight infants. Breastfeed Med. 2021;16:835-842.

- Nommsen-Rivers LA, Dewey KG. Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:334-342.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 756: optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e187-e196.

- Berens P, Labbok M; Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Clinical Protocol #13: contraception during breastfeeding, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:3-12.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, Contraceptive Equity Expert Work Group, and Committee on Ethics. Committee statement no. 1: patient-centered contraceptive counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:350-353.

- Bryant AG, Lyerly AD, DeVane-Johnson S, et al. Hormonal contraception, breastfeeding and bedside advocacy: the case for patient-centered care. Contraception. 2019;99:73-76.

CASE Patient concerned about hormonal contraception’s impact on lactation

A 19-year-old woman (G2P1102) is postpartum day 1 after delivering a baby at 26 weeks’ gestation. When you see her on postpartum rounds, she states that she does not want any hormonal contraception because she heard that it will decrease her milk supply. What are your next steps?

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently updated its policy statement on breastfeeding and the use of human milk to recommend exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and continued breastfeeding, with complementary foods, as mutually desired for 2 years or beyond given evidence of maternal health benefits with breastfeeding longer than 1 year.1

Breastfeeding prevalence—and challenges

Despite maternal and infant benefits associated with lactation, current breastfeeding prevalence in the United States remains suboptimal. In 2019, 24.9% of infants were exclusively breastfed through 6 months and 35.9% were breastfeeding at 12 months.2 Furthermore, disparities in breastfeeding exist, which contribute to health inequities. For example, non-Hispanic Black infants had lower rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months (19.1%) and any breastfeeding at 12 months (24.1%) compared with non-Hispanic White infants (26.9% and 39.4%, respectively).3

While many new mothers intend to breastfeed and initiate breastfeeding in the hospital after delivery, overall and exclusive breastfeeding continuation rates are low, indicating that patients face challenges with breastfeeding after hospital discharge. Many structural and societal barriers to breastfeeding exist, including inadequate social support and parental leave policies.4 Suboptimal maternity care practices during the birth hospitalization may lead to challenges with breastfeeding initiation. Health care practitioners may present additional barriers to breastfeeding due to a lack of knowledge of available resources for patients or incomplete training in breastfeeding counseling and support.

To address our case patient’s concerns, clinicians should be aware of how exogenous progestins may affect breastfeeding physiology, risk factors for breastfeeding difficulty, and the available evidence for safety of hormonal contraception use while breastfeeding.

Physiology of breastfeeding

During the second half of pregnancy, secretory differentiation (lactogenesis I) of mammary alveolar epithelial cells into secretory cells occurs to allow the mammary gland to eventually produce milk.5 After delivery of the placenta, progesterone withdrawal triggers secretory activation (lactogenesis II), which refers to the onset of copious milk production within 2 to 3 days postpartum.5 Most patients experience secretory activation within 72 hours; however, a delay in secretory activation past 72 hours is associated with cessation of any and exclusive breastfeeding at 4 weeks postpartum.6

Impaired lactation can be related to a delay in secretory activation or to insufficient lactation related to low milk supply. Maternal medical comorbidities (for example, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, obesity), breast anatomy (such as insufficient glandular tissue, prior breast reduction surgery), pregnancy-related events (preeclampsia, retained placenta, postpartum hemorrhage), and infant conditions (such as multiple gestation, premature birth, congenital anomalies) all contribute to a risk of impaired lactation.7

Guidance on breastfeeding and hormonal contraception initiation

Early initiation of hormonal contraception poses theoretical concerns about breastfeeding difficulty if exogenous progestin interferes with endogenous signals for onset of milk production. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention US Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) for Contraceptive Use provide recommendations on the safety of contraceptive use in the setting of various medical conditions or patient characteristics based on available data. The MEC uses 4 categories in assessing the safety of contraceptive method use for individuals with specific medical conditions or characteristics: 1, no restrictions exist for use of the contraceptive method; 2, advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks; 3, theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages; and 4, conditions that represent an unacceptable health risk if the method is used.8

In the 2016 guidelines, combined hormonal contraceptives are considered category 4 at less than 21 days postpartum, regardless of breastfeeding status, due to the increased risk of venous thromboembolism in the immediate postpartum period (TABLE 1).8 Progestin-only contraception is considered category 1 in nonbreastfeeding individuals and category 2 in breastfeeding individuals based on overall evidence that found no adverse outcome with breastfeeding or infant outcomes with early initiation of progestin-only contraception (TABLE 1, TABLE 2).8

Since the publication of the 2016 MEC guidelines, several studies have continued to examine breastfeeding and infant outcomes with early initiation of hormonal contraception.

- In a noninferiority randomized controlled trial of immediate versus delayed initiation of a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG IUD), any breastfeeding at 8 weeks in the immediate group was 78% (95% confidence interval [CI], 70%–85%), which was lower than but within the specified noninferiority margin of the delayed breastfeeding group (83%; 95% CI, 75%–90%), indicating that breastfeeding outcomes with immediate initiation of an LNG IUD were not worse compared with delayed initiation.9

- A secondary analysis of a randomized trial that compared intracesarean versus LNG IUD placement at 6 or more weeks postpartum showed no difference in breastfeeding at 6, 12, and 24 weeks after LNG IUD placement.10

- A randomized trial of early (up to 48 hours postpartum) versus placement of an etonogestrel (ENG) implant at 6 or more weeks postpartum showed no difference between groups in infant weight at 12 months.11

- A randomized trial of immediate (within 5 days of delivery) or interval placement of the 2-rod LNG implant (not approved in the United States) showed no difference in change in infant weight from birth to 6 months after delivery, onset of secretory activation, or breastfeeding continuation at 3 and 6 months postpartum.12

- In a prospective cohort study that compared immediate postpartum initiation of ENG versus a 2-rod LNG implant (approved by the FDA but not marketed in the United States), there were no differences in breastfeeding continuation at 24 months and exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum.13

- In a noninferiority randomized controlled trial that compared ENG implant initiation in the delivery room (0–2 hours postdelivery) versus delayed initiation (24–48 hours postdelivery), the time to secretory activation in those who initiated an ENG implant in the delivery room (66.8 [SD, 25.2] hours) was noninferior to delayed initiation (66.0 [SD, 35.3] hours). There also was no difference in ongoing breastfeeding over the first year after delivery and implant use at 12 months.14

- A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial examined breastfeeding outcomes with receipt of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) prior to discharge in women who delivered infants who weighed 1,500 g or less at 32 weeks’ or less gestation. Time to secretory activation was longer in 29 women who received DMPA (103.7 hours) compared with 141 women who did not (88.6 hours; P = .028); however, there was no difference in daily milk production, lactation duration, or infant consumption of mother’s own milk.15

While the overall evidence suggests that early initiation of hormonal contraception does not affect breastfeeding or infant outcomes, it is important for clinicians to recognize the limitations of available data with regard to the populations included in these studies. Specifically, most studies did not include individuals with premature, low birth weight, or multiple gestation infants, who are at higher risk of impaired lactation, and individuals with a higher prevalence of breastfeeding were not included to determine whether early initiation of hormonal contraception would impact breastfeeding. Furthermore, while these studies enrolled participants who planned to breastfeed, data indicate that intentions to initiate and continue exclusive breastfeeding can vary.16 As the reported rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding are consistent with or lower than current US breastfeeding rates, any decrease in breastfeeding exclusivity or duration that may be attributable to hormonal contraception may be unacceptable to those who are strongly motivated to breastfeed.

Continue to: How can clinicians integrate evidence into contraception counseling?...

How can clinicians integrate evidence into contraception counseling?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine offer guidance for how clinicians can address the use of hormonal contraception in breastfeeding patients. Both organizations recommend discussing the risks and benefits of hormonal contraception within the context of each person’s desire to breastfeed, potential for breastfeeding difficulty, and risk of pregnancy so that individuals can make their own informed decisions.17,18

Obstetric care clinicians have an important role in helping patients make informed infant feeding decisions without coercion or pressure. To start these discussions, clinicians can begin by assessing a patient’s breastfeeding goals by asking open-ended questions, such as:

- What have you heard about breastfeeding?

- What are your plans for returning to work or school after delivery?

- How did breastfeeding go with older children?

- What are your plans for feeding this baby?

In addition to gathering information about the patient’s priorities and goals, clinicians should identify any risk factors for breastfeeding challenges in the medical, surgical, or previous breastfeeding history. Clinicians can engage in a patient-centered approach to infant feeding decisions by anticipating any challenges and working together to develop strategies to address these challenges with the patient’s goals in mind.17

When counseling about contraception, a spectrum of approaches exists, from a nondirective information-sharing only model to directive counseling by the clinician. The shared decision-making model lies between these 2 approaches and recognizes the expertise of both the clinician and patient.19 To start these interactions, clinicians can ask about a patient’s reproductive goals by assessing the patient’s needs, values, and preferences for contraception. Potential questions include:

- What kinds of contraceptive methods have you used in the past?

- What is important to you in a contraceptive method?

- How important is it to you to avoid another pregnancy right now?

Clinicians can then share information about different contraceptive methods based on the desired qualities that the patient has identified and how each method fits or does not fit into the patient’s goals and preferences. This collaborative approach facilitates an open dialogue and supports patient autonomy in contraceptive decision-making.

Lastly, clinicians should be cognizant of their own potential biases that could affect their counseling, such as encouraging contraceptive use because of a patient’s young age, parity, or premature delivery, as in our case presentation. Similarly, clinicians also should recognize that breastfeeding and contraceptive decisions are personal and are made with cultural, historical, and social contexts in mind.20 Ultimately, counseling should be patient centered and individualized for each person’s priorities related to infant feeding and pregnancy prevention. ●

CASE Patient concerned about hormonal contraception’s impact on lactation

A 19-year-old woman (G2P1102) is postpartum day 1 after delivering a baby at 26 weeks’ gestation. When you see her on postpartum rounds, she states that she does not want any hormonal contraception because she heard that it will decrease her milk supply. What are your next steps?

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently updated its policy statement on breastfeeding and the use of human milk to recommend exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and continued breastfeeding, with complementary foods, as mutually desired for 2 years or beyond given evidence of maternal health benefits with breastfeeding longer than 1 year.1

Breastfeeding prevalence—and challenges

Despite maternal and infant benefits associated with lactation, current breastfeeding prevalence in the United States remains suboptimal. In 2019, 24.9% of infants were exclusively breastfed through 6 months and 35.9% were breastfeeding at 12 months.2 Furthermore, disparities in breastfeeding exist, which contribute to health inequities. For example, non-Hispanic Black infants had lower rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months (19.1%) and any breastfeeding at 12 months (24.1%) compared with non-Hispanic White infants (26.9% and 39.4%, respectively).3

While many new mothers intend to breastfeed and initiate breastfeeding in the hospital after delivery, overall and exclusive breastfeeding continuation rates are low, indicating that patients face challenges with breastfeeding after hospital discharge. Many structural and societal barriers to breastfeeding exist, including inadequate social support and parental leave policies.4 Suboptimal maternity care practices during the birth hospitalization may lead to challenges with breastfeeding initiation. Health care practitioners may present additional barriers to breastfeeding due to a lack of knowledge of available resources for patients or incomplete training in breastfeeding counseling and support.

To address our case patient’s concerns, clinicians should be aware of how exogenous progestins may affect breastfeeding physiology, risk factors for breastfeeding difficulty, and the available evidence for safety of hormonal contraception use while breastfeeding.

Physiology of breastfeeding

During the second half of pregnancy, secretory differentiation (lactogenesis I) of mammary alveolar epithelial cells into secretory cells occurs to allow the mammary gland to eventually produce milk.5 After delivery of the placenta, progesterone withdrawal triggers secretory activation (lactogenesis II), which refers to the onset of copious milk production within 2 to 3 days postpartum.5 Most patients experience secretory activation within 72 hours; however, a delay in secretory activation past 72 hours is associated with cessation of any and exclusive breastfeeding at 4 weeks postpartum.6

Impaired lactation can be related to a delay in secretory activation or to insufficient lactation related to low milk supply. Maternal medical comorbidities (for example, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, obesity), breast anatomy (such as insufficient glandular tissue, prior breast reduction surgery), pregnancy-related events (preeclampsia, retained placenta, postpartum hemorrhage), and infant conditions (such as multiple gestation, premature birth, congenital anomalies) all contribute to a risk of impaired lactation.7

Guidance on breastfeeding and hormonal contraception initiation

Early initiation of hormonal contraception poses theoretical concerns about breastfeeding difficulty if exogenous progestin interferes with endogenous signals for onset of milk production. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention US Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) for Contraceptive Use provide recommendations on the safety of contraceptive use in the setting of various medical conditions or patient characteristics based on available data. The MEC uses 4 categories in assessing the safety of contraceptive method use for individuals with specific medical conditions or characteristics: 1, no restrictions exist for use of the contraceptive method; 2, advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks; 3, theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages; and 4, conditions that represent an unacceptable health risk if the method is used.8

In the 2016 guidelines, combined hormonal contraceptives are considered category 4 at less than 21 days postpartum, regardless of breastfeeding status, due to the increased risk of venous thromboembolism in the immediate postpartum period (TABLE 1).8 Progestin-only contraception is considered category 1 in nonbreastfeeding individuals and category 2 in breastfeeding individuals based on overall evidence that found no adverse outcome with breastfeeding or infant outcomes with early initiation of progestin-only contraception (TABLE 1, TABLE 2).8

Since the publication of the 2016 MEC guidelines, several studies have continued to examine breastfeeding and infant outcomes with early initiation of hormonal contraception.

- In a noninferiority randomized controlled trial of immediate versus delayed initiation of a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG IUD), any breastfeeding at 8 weeks in the immediate group was 78% (95% confidence interval [CI], 70%–85%), which was lower than but within the specified noninferiority margin of the delayed breastfeeding group (83%; 95% CI, 75%–90%), indicating that breastfeeding outcomes with immediate initiation of an LNG IUD were not worse compared with delayed initiation.9

- A secondary analysis of a randomized trial that compared intracesarean versus LNG IUD placement at 6 or more weeks postpartum showed no difference in breastfeeding at 6, 12, and 24 weeks after LNG IUD placement.10

- A randomized trial of early (up to 48 hours postpartum) versus placement of an etonogestrel (ENG) implant at 6 or more weeks postpartum showed no difference between groups in infant weight at 12 months.11

- A randomized trial of immediate (within 5 days of delivery) or interval placement of the 2-rod LNG implant (not approved in the United States) showed no difference in change in infant weight from birth to 6 months after delivery, onset of secretory activation, or breastfeeding continuation at 3 and 6 months postpartum.12

- In a prospective cohort study that compared immediate postpartum initiation of ENG versus a 2-rod LNG implant (approved by the FDA but not marketed in the United States), there were no differences in breastfeeding continuation at 24 months and exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum.13

- In a noninferiority randomized controlled trial that compared ENG implant initiation in the delivery room (0–2 hours postdelivery) versus delayed initiation (24–48 hours postdelivery), the time to secretory activation in those who initiated an ENG implant in the delivery room (66.8 [SD, 25.2] hours) was noninferior to delayed initiation (66.0 [SD, 35.3] hours). There also was no difference in ongoing breastfeeding over the first year after delivery and implant use at 12 months.14

- A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial examined breastfeeding outcomes with receipt of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) prior to discharge in women who delivered infants who weighed 1,500 g or less at 32 weeks’ or less gestation. Time to secretory activation was longer in 29 women who received DMPA (103.7 hours) compared with 141 women who did not (88.6 hours; P = .028); however, there was no difference in daily milk production, lactation duration, or infant consumption of mother’s own milk.15

While the overall evidence suggests that early initiation of hormonal contraception does not affect breastfeeding or infant outcomes, it is important for clinicians to recognize the limitations of available data with regard to the populations included in these studies. Specifically, most studies did not include individuals with premature, low birth weight, or multiple gestation infants, who are at higher risk of impaired lactation, and individuals with a higher prevalence of breastfeeding were not included to determine whether early initiation of hormonal contraception would impact breastfeeding. Furthermore, while these studies enrolled participants who planned to breastfeed, data indicate that intentions to initiate and continue exclusive breastfeeding can vary.16 As the reported rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding are consistent with or lower than current US breastfeeding rates, any decrease in breastfeeding exclusivity or duration that may be attributable to hormonal contraception may be unacceptable to those who are strongly motivated to breastfeed.

Continue to: How can clinicians integrate evidence into contraception counseling?...

How can clinicians integrate evidence into contraception counseling?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine offer guidance for how clinicians can address the use of hormonal contraception in breastfeeding patients. Both organizations recommend discussing the risks and benefits of hormonal contraception within the context of each person’s desire to breastfeed, potential for breastfeeding difficulty, and risk of pregnancy so that individuals can make their own informed decisions.17,18

Obstetric care clinicians have an important role in helping patients make informed infant feeding decisions without coercion or pressure. To start these discussions, clinicians can begin by assessing a patient’s breastfeeding goals by asking open-ended questions, such as:

- What have you heard about breastfeeding?

- What are your plans for returning to work or school after delivery?

- How did breastfeeding go with older children?

- What are your plans for feeding this baby?

In addition to gathering information about the patient’s priorities and goals, clinicians should identify any risk factors for breastfeeding challenges in the medical, surgical, or previous breastfeeding history. Clinicians can engage in a patient-centered approach to infant feeding decisions by anticipating any challenges and working together to develop strategies to address these challenges with the patient’s goals in mind.17

When counseling about contraception, a spectrum of approaches exists, from a nondirective information-sharing only model to directive counseling by the clinician. The shared decision-making model lies between these 2 approaches and recognizes the expertise of both the clinician and patient.19 To start these interactions, clinicians can ask about a patient’s reproductive goals by assessing the patient’s needs, values, and preferences for contraception. Potential questions include:

- What kinds of contraceptive methods have you used in the past?

- What is important to you in a contraceptive method?

- How important is it to you to avoid another pregnancy right now?

Clinicians can then share information about different contraceptive methods based on the desired qualities that the patient has identified and how each method fits or does not fit into the patient’s goals and preferences. This collaborative approach facilitates an open dialogue and supports patient autonomy in contraceptive decision-making.

Lastly, clinicians should be cognizant of their own potential biases that could affect their counseling, such as encouraging contraceptive use because of a patient’s young age, parity, or premature delivery, as in our case presentation. Similarly, clinicians also should recognize that breastfeeding and contraceptive decisions are personal and are made with cultural, historical, and social contexts in mind.20 Ultimately, counseling should be patient centered and individualized for each person’s priorities related to infant feeding and pregnancy prevention. ●

- Meek JY, Noble L; Section on Breastfeeding. Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2022;150:e2022057988.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding report card, United States 2022. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2022-Breast feeding-Report-Card-H.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding by sociodemographic characteristic among children born in 2019. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/data-files/2019/rates-any-exclusive-bf-socio-dem-2019.html

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 821: barriers to breastfeeding: supporting initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e54-e62.

- Pang WW, Hartmann PE. Initiation of human lactation: secretory differentiation and secretory activation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12:211-221.

- Brownell E, Howard CR, Lawrence RA, et al. Delayed onset lactogenesis II predicts the cessation of any or exclusive breastfeeding. J Pediatr. 2012;161:608-614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 820: breastfeeding challenges. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e42-e53.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(RR-3):1-104.

- Turok DK, Leeman L, Sanders JN, et al. Immediate postpartum levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding outcomes: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:665.e1-665.e8.

- Levi EE, Findley MK, Avila K, et al. Placement of levonorgestrel intrauterine device at the time of cesarean delivery and the effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13:674-679.

- Carmo LSMP, Braga GC, Ferriani RA, et al. Timing of etonogestrel-releasing implants and growth of breastfed infants: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:100-107.

- Averbach S, Kakaire O, McDiehl R, et al. The effect of immediate postpartum levonorgestrel contraceptive implant use on breastfeeding and infant growth: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2019;99:87-93.

- Krashin JW, Lemani C, Nkambule J, et al. A comparison of breastfeeding exclusivity and duration rates between immediate postpartum levonorgestrel versus etonogestrel implant users: a prospective cohort study. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14:69-76.

- Henkel A, Lerma K, Reyes G, et al. Lactogenesis and breastfeeding after immediate vs delayed birth-hospitalization insertion of etonogestrel contraceptive implant: a noninferiority trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023; 228:55.e1-55.e9.

- Parker LA, Sullivan S, Cacho N, et al. Effect of postpartum depo medroxyprogesterone acetate on lactation in mothers of very low-birth-weight infants. Breastfeed Med. 2021;16:835-842.

- Nommsen-Rivers LA, Dewey KG. Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:334-342.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 756: optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e187-e196.

- Berens P, Labbok M; Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Clinical Protocol #13: contraception during breastfeeding, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:3-12.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, Contraceptive Equity Expert Work Group, and Committee on Ethics. Committee statement no. 1: patient-centered contraceptive counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:350-353.

- Bryant AG, Lyerly AD, DeVane-Johnson S, et al. Hormonal contraception, breastfeeding and bedside advocacy: the case for patient-centered care. Contraception. 2019;99:73-76.

- Meek JY, Noble L; Section on Breastfeeding. Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2022;150:e2022057988.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding report card, United States 2022. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2022-Breast feeding-Report-Card-H.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding by sociodemographic characteristic among children born in 2019. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/data-files/2019/rates-any-exclusive-bf-socio-dem-2019.html

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 821: barriers to breastfeeding: supporting initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e54-e62.

- Pang WW, Hartmann PE. Initiation of human lactation: secretory differentiation and secretory activation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12:211-221.

- Brownell E, Howard CR, Lawrence RA, et al. Delayed onset lactogenesis II predicts the cessation of any or exclusive breastfeeding. J Pediatr. 2012;161:608-614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 820: breastfeeding challenges. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e42-e53.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(RR-3):1-104.

- Turok DK, Leeman L, Sanders JN, et al. Immediate postpartum levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding outcomes: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:665.e1-665.e8.

- Levi EE, Findley MK, Avila K, et al. Placement of levonorgestrel intrauterine device at the time of cesarean delivery and the effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13:674-679.

- Carmo LSMP, Braga GC, Ferriani RA, et al. Timing of etonogestrel-releasing implants and growth of breastfed infants: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:100-107.

- Averbach S, Kakaire O, McDiehl R, et al. The effect of immediate postpartum levonorgestrel contraceptive implant use on breastfeeding and infant growth: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2019;99:87-93.

- Krashin JW, Lemani C, Nkambule J, et al. A comparison of breastfeeding exclusivity and duration rates between immediate postpartum levonorgestrel versus etonogestrel implant users: a prospective cohort study. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14:69-76.

- Henkel A, Lerma K, Reyes G, et al. Lactogenesis and breastfeeding after immediate vs delayed birth-hospitalization insertion of etonogestrel contraceptive implant: a noninferiority trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023; 228:55.e1-55.e9.

- Parker LA, Sullivan S, Cacho N, et al. Effect of postpartum depo medroxyprogesterone acetate on lactation in mothers of very low-birth-weight infants. Breastfeed Med. 2021;16:835-842.

- Nommsen-Rivers LA, Dewey KG. Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:334-342.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 756: optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e187-e196.

- Berens P, Labbok M; Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Clinical Protocol #13: contraception during breastfeeding, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:3-12.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, Contraceptive Equity Expert Work Group, and Committee on Ethics. Committee statement no. 1: patient-centered contraceptive counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:350-353.

- Bryant AG, Lyerly AD, DeVane-Johnson S, et al. Hormonal contraception, breastfeeding and bedside advocacy: the case for patient-centered care. Contraception. 2019;99:73-76.

Is the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system more effective than the copper IUD at preventing pregnancy?

Both the LNG-IUS and the copper IUD are highly effective at pregnancy prevention. However, large-scale comparative studies are lacking. These findings from the European Active Surveillance Study for Intrauterine Devices (EURAS IUD), an investigation of new users of the LNG-IUS (20 µg/day) and copper IUD (>30 different types) in Austria, Finland, Germany, Poland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, confirm the low contraceptive failure rate for both devices.

The primary objective of this trial was to compare uterine perforation rates,1 but the results of a planned secondary analysis comparing contraceptive effectiveness may be of more interest to patients and providers.

Details of the study

Women who had a newly inserted IUD during the study period were eligible for recruitment. These women and their inserting health care provider then completed a follow-up questionnaire 12 months after enrollment to assess for pregnancy or any potential IUD complication.

In total, 61,448 women were enrolled, and 58,324 patients (41,001 using the LNG-IUS and 17,323 using the copper IUD) were included in the analysis. Only 1.7% of LNG-IUS users and 2.8% of copper IUD users were lost to follow-up. Women using the LNG-IUS were older than those using the copper IUD (mean age of 37.4 vs 33.3 years, respectively). About 43% and 24% of LNG-IUS and copper IUD users, respectively, were age 40 or older at the time of IUD insertion.

Strengths and limitations

The large sample size and low number of women lost to follow-up are strengths of this study. A major weakness: The indication for IUD insertion was not recorded. Nor was the risk of pregnancy assessed at enrollment.

Overall, the age of the study population was older than is typically found in a contraceptive efficacy trial, which generally covers the age range of 18 to 35 years.

Because women chose their type of IUD (as opposed to random allocation), variations in underlying fertility, age, and other confounders of efficacy cannot be accounted for fully with statistical analyses. The variation in age strongly suggests that women may have chosen the LNG-IUS for reasons other than contraception.

Furthermore, more than 30 types of copper IUDs were inserted during the study period, and small variations in contraceptive efficacy from one type to another may contribute to the overall difference in failure rates between the LNG-IUS and copper IUD. Although Heinemann and colleagues did perform an analysis of failure rates by copper content and found no differences between users of IUDs with less than 300 mm2 and those with at least 300 mm2 of copper, earlier prospective randomized trials show differences in contraceptive efficacy by device type and amount of copper.2

What this evidence means for practice

The LNG-IUS may be a more effective contraceptive than the copper IUD, but both possess excellent contraceptive efficacy. Prospective randomized trials, although much smaller than this nonrandomized cohort study, do not demonstrate differences in contraceptive efficacy between the LNG-IUS and copper IUD.3 The small difference in contraceptive failure rates (less than 1 in 200 women), if real, should not be the deciding factor for choosing one IUD over the other.

— Melissa J. Chen, MD, MPH, and Mitchell D. Creinin, MDShare your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Do Minh T. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91(4):274–279.

2. Thonneau PF, Almont T. Contraceptive efficacy of intrauterine devices. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(3):248–253.

3. Sivin I, el Mahgoub S, McCarthy T, et al. Long-term contraception with the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T380Ag intrauterine devices: a five-year randomized study. Contraception. 1990;42(4):361–378.

Both the LNG-IUS and the copper IUD are highly effective at pregnancy prevention. However, large-scale comparative studies are lacking. These findings from the European Active Surveillance Study for Intrauterine Devices (EURAS IUD), an investigation of new users of the LNG-IUS (20 µg/day) and copper IUD (>30 different types) in Austria, Finland, Germany, Poland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, confirm the low contraceptive failure rate for both devices.

The primary objective of this trial was to compare uterine perforation rates,1 but the results of a planned secondary analysis comparing contraceptive effectiveness may be of more interest to patients and providers.

Details of the study

Women who had a newly inserted IUD during the study period were eligible for recruitment. These women and their inserting health care provider then completed a follow-up questionnaire 12 months after enrollment to assess for pregnancy or any potential IUD complication.

In total, 61,448 women were enrolled, and 58,324 patients (41,001 using the LNG-IUS and 17,323 using the copper IUD) were included in the analysis. Only 1.7% of LNG-IUS users and 2.8% of copper IUD users were lost to follow-up. Women using the LNG-IUS were older than those using the copper IUD (mean age of 37.4 vs 33.3 years, respectively). About 43% and 24% of LNG-IUS and copper IUD users, respectively, were age 40 or older at the time of IUD insertion.

Strengths and limitations

The large sample size and low number of women lost to follow-up are strengths of this study. A major weakness: The indication for IUD insertion was not recorded. Nor was the risk of pregnancy assessed at enrollment.

Overall, the age of the study population was older than is typically found in a contraceptive efficacy trial, which generally covers the age range of 18 to 35 years.

Because women chose their type of IUD (as opposed to random allocation), variations in underlying fertility, age, and other confounders of efficacy cannot be accounted for fully with statistical analyses. The variation in age strongly suggests that women may have chosen the LNG-IUS for reasons other than contraception.

Furthermore, more than 30 types of copper IUDs were inserted during the study period, and small variations in contraceptive efficacy from one type to another may contribute to the overall difference in failure rates between the LNG-IUS and copper IUD. Although Heinemann and colleagues did perform an analysis of failure rates by copper content and found no differences between users of IUDs with less than 300 mm2 and those with at least 300 mm2 of copper, earlier prospective randomized trials show differences in contraceptive efficacy by device type and amount of copper.2

What this evidence means for practice

The LNG-IUS may be a more effective contraceptive than the copper IUD, but both possess excellent contraceptive efficacy. Prospective randomized trials, although much smaller than this nonrandomized cohort study, do not demonstrate differences in contraceptive efficacy between the LNG-IUS and copper IUD.3 The small difference in contraceptive failure rates (less than 1 in 200 women), if real, should not be the deciding factor for choosing one IUD over the other.

— Melissa J. Chen, MD, MPH, and Mitchell D. Creinin, MDShare your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Both the LNG-IUS and the copper IUD are highly effective at pregnancy prevention. However, large-scale comparative studies are lacking. These findings from the European Active Surveillance Study for Intrauterine Devices (EURAS IUD), an investigation of new users of the LNG-IUS (20 µg/day) and copper IUD (>30 different types) in Austria, Finland, Germany, Poland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, confirm the low contraceptive failure rate for both devices.

The primary objective of this trial was to compare uterine perforation rates,1 but the results of a planned secondary analysis comparing contraceptive effectiveness may be of more interest to patients and providers.

Details of the study

Women who had a newly inserted IUD during the study period were eligible for recruitment. These women and their inserting health care provider then completed a follow-up questionnaire 12 months after enrollment to assess for pregnancy or any potential IUD complication.

In total, 61,448 women were enrolled, and 58,324 patients (41,001 using the LNG-IUS and 17,323 using the copper IUD) were included in the analysis. Only 1.7% of LNG-IUS users and 2.8% of copper IUD users were lost to follow-up. Women using the LNG-IUS were older than those using the copper IUD (mean age of 37.4 vs 33.3 years, respectively). About 43% and 24% of LNG-IUS and copper IUD users, respectively, were age 40 or older at the time of IUD insertion.

Strengths and limitations

The large sample size and low number of women lost to follow-up are strengths of this study. A major weakness: The indication for IUD insertion was not recorded. Nor was the risk of pregnancy assessed at enrollment.

Overall, the age of the study population was older than is typically found in a contraceptive efficacy trial, which generally covers the age range of 18 to 35 years.

Because women chose their type of IUD (as opposed to random allocation), variations in underlying fertility, age, and other confounders of efficacy cannot be accounted for fully with statistical analyses. The variation in age strongly suggests that women may have chosen the LNG-IUS for reasons other than contraception.

Furthermore, more than 30 types of copper IUDs were inserted during the study period, and small variations in contraceptive efficacy from one type to another may contribute to the overall difference in failure rates between the LNG-IUS and copper IUD. Although Heinemann and colleagues did perform an analysis of failure rates by copper content and found no differences between users of IUDs with less than 300 mm2 and those with at least 300 mm2 of copper, earlier prospective randomized trials show differences in contraceptive efficacy by device type and amount of copper.2

What this evidence means for practice

The LNG-IUS may be a more effective contraceptive than the copper IUD, but both possess excellent contraceptive efficacy. Prospective randomized trials, although much smaller than this nonrandomized cohort study, do not demonstrate differences in contraceptive efficacy between the LNG-IUS and copper IUD.3 The small difference in contraceptive failure rates (less than 1 in 200 women), if real, should not be the deciding factor for choosing one IUD over the other.

— Melissa J. Chen, MD, MPH, and Mitchell D. Creinin, MDShare your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Do Minh T. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91(4):274–279.

2. Thonneau PF, Almont T. Contraceptive efficacy of intrauterine devices. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(3):248–253.

3. Sivin I, el Mahgoub S, McCarthy T, et al. Long-term contraception with the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T380Ag intrauterine devices: a five-year randomized study. Contraception. 1990;42(4):361–378.

1. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Do Minh T. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91(4):274–279.

2. Thonneau PF, Almont T. Contraceptive efficacy of intrauterine devices. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(3):248–253.

3. Sivin I, el Mahgoub S, McCarthy T, et al. Long-term contraception with the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T380Ag intrauterine devices: a five-year randomized study. Contraception. 1990;42(4):361–378.

2014 Update on Contraception

Unintended pregnancy remains an important public health priority in the United States. Correct and consistent use of effective contraception can help women achieve appropriate interpregnancy intervals and desired family size, whereas inconsistent or non-use of contraceptive methods contributes to the majority of unintended pregnancies.

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, such as implants and intrauterine devices, have effectiveness rates similar to those of permanent sterilization, and these methods are becoming more popular among American women. The proportion of women using LARC methods increased from 2.4% in 2002 to 8.5% in 2009.1

Sterilization continues to be a common method of contraception, with 32% of women relying on female or male sterilization in 2009.1 For women who are not using contraception regularly or who experience a failure in their method, emergency contraception is a viable back-up plan.

In this article, we will review the latest data on contraceptive efficacy in three different contexts:

- implant placement in the immediate postpartum period

- emergency contraception (EC) with the copper intrauterine device (IUD)

- sterilization via hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic approaches.

Immediate postpartum placement of the contraceptive implant saves money

Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):481.e1–e7.

Han L, Teal SB, Sheeder J, Tocce K. Preventing repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Is immediate postpartum insertion of the contraceptive implant cost effective? [published online ahead of print March 11, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.015.

Although teen birth rates have been declining in the United States in recent years, repeat teen births still pose significant health and socioeconomic challenges for young mothers, their children, and society. Adolescent mothers face barriers in completing their education and obtaining work experience. Repeat teen mothers are also more likely to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth or delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. Families of adolescent mothers are not the only ones who are affected by teen childbearing. In fact, US taxpayers spend about $11 billion each year on costs related to teen pregnancy.2

The immediate postpartum period is a time when effective LARC methods can be initiated to decrease the risk of rapid repeat pregnancy.

Details of the study by Tocce and colleagues

Tocce and colleagues report the results of a prospective observational study that compared adolescents who chose postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion with those who elected to use no contraception or initiate contraception at the usual interval (condoms, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills at any time after delivery, combined hormonal contraception after 4 weeks postpartum, implant insertion after 4 weeks postpartum, and intrauterine device placement at 6 weeks after delivery).

Of adolescents who chose immediate postpartum implant placement, 88.6% were still using this method at 12 months postpartum. In comparison, only 53.6% of adolescents in the control group were using a highly effective contraceptive method at 12 months postpartum (TABLE).

| Contraceptive method | Immediate postpartum implant (n = 149) | Control* (n = 166) |

| Implant | 132 (88.6%) | 35 (21.1%) |

| Intrauterine device | 6 (4.0%) | 51 (30.7%) |

| Female sterilization | 0 | 3 (01.8%) |

| Total using highly effective method† | 138 (92.6%) | 89 (53.6%) |

* The control group consisted of women who elected to use no contraception or initiate contraception at the usual postpartum interval (condoms, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills at any time after delivery, combined hormonal contraception after 4 weeks postpartum, implant insertion after 4 weeks postpartum, and intrauterine device placement at 6 weeks after delivery). † P<.0001, Fisher exact test.Adapted from: Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):481.e1–e7. | ||

The difference in repeat pregnancy rates was even more compelling. At 12 months postpartum, the pregnancy rate was 2.6% for women who had chosen an immediate postpartum implant, compared with 18.6% in the control group (P<.001).

One significant barrier to immediate postpartum LARC placement is reimbursement policies; hospitals are reimbursed a single global fee for all of the hospital care, so insertion of an expensive contraceptive implant during the hospital stay is not reimbursed. However, if a woman returns to the office for insertion, the provider receives full reimbursement if she has coverage for the product.

A look at cost effectiveness

With this in mind, Han and colleagues determined the cost effectiveness of immediate postpartum implant placement using the results from the observational study from Tocce et al. The costs of implant insertion and removal were calculated, as well as the costs associated with various obstetric or gynecologic outcomes, including prenatal care, vaginal or cesarean delivery, infant medical care for the first year of life, and management of ectopic pregnancy or spontaneous miscarriage. The contraceptive costs for the comparison group were not included in the analysis because these costs would represent baseline contraceptive costs incurred by Medicaid.

Significant cost savings were found with immediate postpartum implant placement over time; specifically, $0.78, $3.54, and $6.50 were saved for every dollar spent at 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively. To be clear, this analysis was limited to contraceptive implant placement, and cannot be directly applied to immediate postpartum intrauterine device insertion.

What this evidence means for practice

Among adolescents who received immediate postpartum implant placement, contraceptive continuation rates were higher and repeat teen birth rates were lower, translating into overall cost savings for state Medicaid programs. Furthermore, young mothers and their families also experience health, social, and economic benefits from a delay in childbearing.

In accordance with the findings of Han and colleagues, the South Carolina Medicaid program is the first to implement reimbursement for inpatient postpartum LARC insertion. Other states should evaluate their own policies for inpatient LARC reimbursement and take into consideration the potential for cost savings

More evidence suggests the copper IUD is the preferred emergency contraceptive

Turok DK, Jacobson JC, Dermish Amna I, et al. Emergency contraception with a copper IUD or oral levonorgestrel: An observational study of 1-year pregnancy rates. Contraception. 2014;89(3):222–228.

Several options for EC exist, but only the copper IUD also can be continued as an effective method of contraception. Despite its dual roles in pregnancy prevention, the copper IUD remains underutilized, compared with oral EC methods. Women who seek EC are motivated to reduce their risk of pregnancy. However, they may not be receiving the most effective method to avoid pregnancy. A survey of 816 emergency contraception providers revealed that 85% of respondents had never offered the copper IUD as a method of EC to their patients.3 This represents a lost opportunity, as the copper IUD would be ideal for women who desire an effective form of EC that also can be continued as contraception.

Details of the trial

Turok and colleagues conducted a prospective observational trial comparing oral levonorgestrel (LNG) with copper IUD insertion in women seeking EC. Women who were interested in participating received scripted counseling on both methods and were given their desired method free of charge.

In this study, almost 40% (215/542) of women chose the copper IUD for EC. However, the providers in this study were unable to place the IUD in 20% of these women. The women who chose not to receive an IUD or who did not have an IUD placed received LNG EC.

There were four pregnancies from EC failures in the first month in the LNG group, compared with none in the IUD group. After 1 year, the risk of pregnancy in women who chose the copper IUD (including the women who were unable to have the device placed) was lower than in women who chose LNG (odds ratio [OR], 0.50; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–0.96).

In an analysis based on the actual method received, the risk of pregnancy in the IUD group was even lower (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.18–0.80).

At 1 year, 60% of women in the copper IUD group were using a highly effective method of contraception, specifically an IUD, implant, or sterilization, compared with 10% in the LNG group.

What this evidence means for practice

When given the option, almost 50% of women chose the copper IUD to reduce their risk of pregnancy. Women who received a copper IUD were more likely to be using a highly effective method of contraception and less likely to experience an unintended pregnancy at 1 year than women who chose LNG EC.

We need to counsel our patients on the differences in efficacy between the methods and offer copper IUDs to eligible women.

Hysteroscopic sterilization may not be as effective as we thought

Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Smith KJ, Xu X. Probability of pregnancy after sterilization: A comparison of hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic sterilization [published online ahead of print April 24, 2014]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.03.010.

Since its introduction in 2002, hysteroscopic sterilization has become a popular method of sterilization. It has many potential advantages over laparoscopic sterilization, including the ability to perform the procedure in an office setting without general anesthesia or abdominal incisions. However, there are also disadvantages to hysteroscopic sterilization, as we pointed out in this Update last year, such as a risk of unsuccessful procedure completion on the first attempt and the need for contraception until tubal occlusion is confirmed.

There are limited data on the effectiveness of hysteroscopic sterilization, and there are no prospective studies comparing hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization. Given the rare outcome of unintended pregnancy with both procedures, based on published literature, a prospective study is unfeasible. An inherent weakness of large clinical trials or retrospective reports of hysteroscopic sterilization success is that only women who had successful completion of the procedure can be included. Two recent reports that demonstrate that completed hysteroscopic sterilization procedures are highly effective highlighted this “weakness.”4,5 However, these data do not reflect “real-life” practice; there are no intent-to-treat data on pregnancy rates among women who choose this option but are unable to fully complete the procedure.

Details of the study

To evaluate real-life outcomes, Gariepy and colleagues performed a decision analysis to estimate the probability of pregnancy after hysteroscopic sterilization and laparoscopic approaches with silicone rubber band application and bipolar coagulation. Using a Markov state-transition model, the authors could determine the probability of pregnancy over a 10-year period for all types of sterilization. For hysteroscopic sterilization, each of the multiple steps, from coil placement to use of alternative contraception in the interim period to follow-up confirmation of tubal occlusion, could be included.

At 10 years, the expected cumulative pregnancy rates per 1,000 women were 96, 24, and 30 for hysteroscopic sterilization, laparoscopic silicone rubber band application, and laparoscopic bipolar coagulation, respectively. For hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization to be equal in effectiveness, the success of laparoscopic sterilization would need to decrease to less than 90% from 99% and hysteroscopic coil placement or follow-up would need to improve.

The authors concluded that the effectiveness of sterilization does vary significantly bythe method used, and rankings of effectiveness should differentiate between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization.

What this evidence means for practice

When counseling women about sterilization, we should discuss the advantages and disadvantages of hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic approaches and disclose the efficacy rates of each method.

The issue is not that the hysteroscopic sterilization procedure is less effective than laparoscopic sterilization. The real take-home point is that women choosing to attempt hysteroscopic sterilization are more likely to experience an unintended pregnancy within the next 10 years than women presenting for laparoscopic sterilization.

Each year, 345,000 US women undergo interval sterilization.6 If hysteroscopic sterilization were attempted as the preferred method for all of these women (as compared with laparoscopic sterilization) in just 1 year, then an additional 22,770 pregnancies would occur for this group of women over the ensuing 10 years. With the current technology, hysteroscopic sterilization should be reserved for appropriate candidates, such as women who may face higher risks from laparoscopy.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

1. Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007-2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897.

2. Centers for Disease Control. Vital signs: Repeat births among teens—United States, 2007–2010. MMWR. 2013;62(13):249–255.

3. Harper CC, Speidel JJ, Drey EA, Trussell J, Blum M, Darney PD. Copper intrauterine device for emergency contraception: Clinical practice among contraceptive providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2 Pt 1):220–226.

4. Munro MG, Nichols JE, Levy B, Vleugels MP, Veersema S. Hysteroscopic sterilization: 10-year retrospective analysis of worldwide pregnancy reports. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(2):245–251.

5. Fernandez H, Legendre G, Blein C, Lamarsalle L, Panel P. Tubal sterilization: Pregnancy rates after hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic sterilization in France, 2006–2010 [published online ahead of print May 14, 2014]. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.04.043.

6. Bartz D, Greenberg JA. Sterilization in the United States. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(1):23–32.

Unintended pregnancy remains an important public health priority in the United States. Correct and consistent use of effective contraception can help women achieve appropriate interpregnancy intervals and desired family size, whereas inconsistent or non-use of contraceptive methods contributes to the majority of unintended pregnancies.

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, such as implants and intrauterine devices, have effectiveness rates similar to those of permanent sterilization, and these methods are becoming more popular among American women. The proportion of women using LARC methods increased from 2.4% in 2002 to 8.5% in 2009.1

Sterilization continues to be a common method of contraception, with 32% of women relying on female or male sterilization in 2009.1 For women who are not using contraception regularly or who experience a failure in their method, emergency contraception is a viable back-up plan.

In this article, we will review the latest data on contraceptive efficacy in three different contexts:

- implant placement in the immediate postpartum period

- emergency contraception (EC) with the copper intrauterine device (IUD)

- sterilization via hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic approaches.

Immediate postpartum placement of the contraceptive implant saves money

Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):481.e1–e7.

Han L, Teal SB, Sheeder J, Tocce K. Preventing repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Is immediate postpartum insertion of the contraceptive implant cost effective? [published online ahead of print March 11, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.015.

Although teen birth rates have been declining in the United States in recent years, repeat teen births still pose significant health and socioeconomic challenges for young mothers, their children, and society. Adolescent mothers face barriers in completing their education and obtaining work experience. Repeat teen mothers are also more likely to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth or delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. Families of adolescent mothers are not the only ones who are affected by teen childbearing. In fact, US taxpayers spend about $11 billion each year on costs related to teen pregnancy.2

The immediate postpartum period is a time when effective LARC methods can be initiated to decrease the risk of rapid repeat pregnancy.

Details of the study by Tocce and colleagues

Tocce and colleagues report the results of a prospective observational study that compared adolescents who chose postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion with those who elected to use no contraception or initiate contraception at the usual interval (condoms, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills at any time after delivery, combined hormonal contraception after 4 weeks postpartum, implant insertion after 4 weeks postpartum, and intrauterine device placement at 6 weeks after delivery).

Of adolescents who chose immediate postpartum implant placement, 88.6% were still using this method at 12 months postpartum. In comparison, only 53.6% of adolescents in the control group were using a highly effective contraceptive method at 12 months postpartum (TABLE).

| Contraceptive method | Immediate postpartum implant (n = 149) | Control* (n = 166) |

| Implant | 132 (88.6%) | 35 (21.1%) |

| Intrauterine device | 6 (4.0%) | 51 (30.7%) |

| Female sterilization | 0 | 3 (01.8%) |

| Total using highly effective method† | 138 (92.6%) | 89 (53.6%) |

* The control group consisted of women who elected to use no contraception or initiate contraception at the usual postpartum interval (condoms, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills at any time after delivery, combined hormonal contraception after 4 weeks postpartum, implant insertion after 4 weeks postpartum, and intrauterine device placement at 6 weeks after delivery). † P<.0001, Fisher exact test.Adapted from: Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):481.e1–e7. | ||