User login

How to safeguard the ureter and repair surgical injury

The author has no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Inadvertent ureteral transection

A gynecologic surgeon operates via Pfannenstiel incision to remove a 12-cm complex left adnexal mass from a 36-year-old obese woman. When she discovers that the mass is densely adherent to the pelvic peritoneum, the surgeon incises the peritoneum lateral to the mass and opens the retroperitoneal space. However, the size and relative immobility of the mass, coupled with the low transverse incision, impair visualization of retroperitoneal structures.

The surgeon clamps and divides the ovarian vessels above the mass but, afterward, suspects that the ureter has been transected and that its ends are included within the clamps. She separates the ovarian vessels above the clamp and ligates them, at which time transection of the ureter is confirmed.

How should she proceed?

The ureter is intimately associated with the female internal genitalia in a way that challenges the gynecologic surgeon to avoid it. In a small percentage of cases involving surgical extirpation in a woman who has severe pelvic pathology, ureteral injury may be inevitable.

Several variables predispose a patient to ureteral injury, including limited exposure, as in the opening case. Others include distorted anatomy of the urinary tract relative to internal genitalia and operations that require extensive resection of pelvic tissues.

This article describes:

- prevention and intraoperative recognition of ureteral injury during gynecologic surgery

- management of intraoperatively recognized ureteral injury.

Maintain a high index of suspicion

The surgeon in the opening case has already taken the first and most important step in ensuring a good outcome: She suspected ureteral injury. In high-risk situations, intraoperative recognition of ureteral injury is more likely when the operative field is inspected thoroughly during and at the conclusion of the surgical procedure.

In a high-risk case, the combined use of intravenous indigo carmine, careful inspection of the operative field, cystoscopy, and ureteral dissection is recommended and should be routine.

Common sites of injury

During gynecologic surgery, the ureter is susceptible to injury along its entire course through the pelvis (see “The ureter takes a course fraught with hazard,”).

During adnexectomy, the gonadal vessels are generally ligated 2 to 3 cm above the adnexa. The ureter lies in close proximity to these vessels and may inadvertently be included in the ligation.

During hysterectomy, the ureter is susceptible to injury as it passes through the parametrium a short distance from the uterus and vaginal fornix.

Sutures placed in the posterior lateral cul de sac during prolapse surgery lie near the midpelvic ureter, and sutures placed during vaginal cuff closure, anterior colporrhaphy, and retropubic urethropexy are in close proximity to the trigonal portion of the ureter.

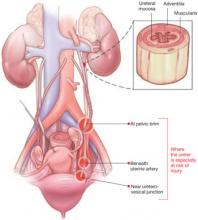

The ureter extends from the renal pelvis to the bladder, with a length that ranges from 25 to 30 cm, depending on the patient’s height. It crosses the pelvic brim near the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, where it becomes the “pelvic” ureter. The abdominal and pelvic portions of the ureter are approximately equal in length.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ROB FLEWELL FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

The blood supply of the ureter derives from branches of the major arterial system of the lower abdomen and pelvis. These branches reach the medial aspect of the abdominal ureter and the lateral side of the pelvic ureter to form an anastomotic vascular network protected by an adventitial layer surrounding the ureter.

The ureter is attached to the posterior lateral pelvic peritoneum running dorsal to ovarian vessels. At the midpelvis, it separates from the peritoneum to pierce the base of the broad ligament underneath the uterine artery. At this point, the ureter is about 1.5 to 2 cm lateral to the uterus and curves medially and ventrally, tunneling through the cardinal and vesicovaginal ligaments to enter the bladder trigone.

Risky procedures

In gynecologic surgery, ureteral injury occurs most often during abdominal hysterectomy—probably because of how frequently this operation is performed and the range of pathology managed. The incidence of ureteral injury is much higher during abdominal hysterectomy than vaginal hysterectomy.1-4

Laparoscopic hysterectomy also has been associated with a higher incidence of ureteral injury, especially in the early phase of training.5,6 Possible explanations include:

- greater difficulty identifying the ureter

- a steeper learning curve

- more frequent use of energy to hemostatically divide pedicles, with the potential for thermal injury

- less traction–countertraction, resulting in dissection closer to the ureter

- management of complex pathology.

Although the overall incidence of ureteral injury during adnexectomy is low, it is probably much higher in women undergoing this procedure after a previous hysterectomy or in the presence of complex adnexal pathology.

When injury is likely

Compromised exposure, distorted anatomy, and certain procedures can heighten the risk of ureteral injury. Large tumors may limit the ability of the surgeon to visualize or palpate the ureter (FIGURE 1). Extensive adhesions may cause similar difficulties, and a small incision or obesity may hinder identification of pelvic sidewall structures.

A number of pathologic conditions can distort the anatomy of the ureter, especially as it relates to the female genital tract:

- Malignancies such as ovarian cancer often encroach on and occasionally encase the ureter

- Pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, and a history of surgery or pelvic radiotherapy can retract and encase the ureter toward the gynecologic tract

- Some masses expand against the lower ureter, such as cervical or broad-ligament leiomyomata or placenta previa with accreta

- During vaginal hysterectomy for complete uterine prolapse, the ureters frequently extend beyond the introitus well within the operative field

- Congenital anomalies of the ureter or hydroureter can also cause distortion.

Even in the presence of relatively normal anatomy, certain procedures predispose the ureter to injury. For example, radical hysterectomy involves the almost complete separation of the pelvic ureter from the gynecologic tract and its surrounding soft tissue. When pelvic pathology is significant, the plane of dissection will always be near the ureter.

FIGURE 1 Access to the ureter is obstructed, putting it in jeopardy

Large tumors may limit the ability of the surgeon to visualize or palpate the ureter.

Prevention is the best strategy

At least 50% of ureteral injuries reported during gynecologic surgery have occurred in the absence of a recognizable risk factor.2,7 Nevertheless, knowledge of anatomy and the ability to recognize situations in which there is an elevated risk for ureteral injury will best enable the surgeon to prevent such injury.

When a high-risk situation is encountered, critical preventive steps include:

- adequate exposure

- competent assistance

- exposure of the path of the ureter through the planned course of dissection. Dissecting the ureter beyond this area is usually unnecessary and may itself cause injury.

Skip preoperative IVP in most cases

The vast majority of women who undergo gynecologic surgery do not benefit from preoperative intravenous pyelography (IVP). This measure does not appear to reduce the likelihood of ureteral injury, even in the face of obvious gynecologic disease. However, preoperative identification of obvious ureteral involvement by the disease process is useful. In such cases, the plane of dissection will probably lie closer to the ureter. One of the goals of surgery will then be to clear the urinary tract from the affected area.

When there is a high index of suspicion of an abnormality such as obstruction, intrinsic ureteral endometriosis, or congenital anomaly, preoperative IVP is indicated.

A stent may be helpful in some cases

Ureteral stents are sometimes placed in order to aid in identification and dissection of the ureters during surgery. Some authors of reports on this topic, including Hoffman, believe that stents are useful in certain situations, such as excision of an ovarian remnant, radical vaginal hysterectomy, and when pelvic organs are encased by malignant ovarian tumors. However, stents do not clearly reduce the risk of injury and, in some cases, may increase the risk by providing a false sense of security and predisposing the ureter to adventitial injury during difficult dissection.

Anticipate the effects of disease

The surgeon must have a thorough knowledge of the gynecologic disease process as it relates to surgery involving the urinary tract. For example, an ovarian remnant will almost always be somewhat densely adherent to the pelvic ureter. When severe endometriosis involves the posterior leaf of the broad ligament, the ureter will often be fibrotically retracted toward the operative field.

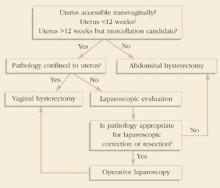

Certain procedures have special challenges. During resection of adnexa, for example, it is important that the ureter be identified in the retroperitoneum before the ovarian vessels are ligated. During hysterectomy, soft tissues that contain the bladder and ureters should be mobilized caudally and laterally, respectively, creating a U-shaped region (“U” for urinary tract, FIGURE 2) to which the surgeon must limit dissection.

FIGURE 2 During hysterectomy, mobilize the bladder and ureter

Mobilize the soft tissues that contain the bladder and ureters caudally and laterally, respectively, creating a U-shaped region. During division of the paracervical tissues, the surgeon must remain within this region.

Intraoperative detection

Two main types of ureteral injury occur during gynecologic surgery: transection and destruction. The latter includes ligation, crushing, devascularization, and thermal injury.

Intraoperative detection of ureteral injury is more likely when the surgeon recognizes at the outset that the operation places the ureter at increased risk. When dissection has been difficult or complicated for any reason, be concerned about possible injury.

In general, ureteral injury is first recognized by careful inspection of the surgical field. Begin by instilling 5 ml of indigo carmine intravenously. Once the dye begins to appear in the Foley catheter, inspect the area of dissection under a small amount of irrigation fluid, looking for extravasation of dye that indicates partial or complete transection.

If no injury is identified, cystoscopy is the next step. I perform all major abdominal operations with the patient in the low lithotomy position, which provides easy access to the perineum. Cystoscopic identification of urine jetting from both ureteral orifices confirms patency. When only wisps of dye are observed, it is likely that the ureter in question has been partially occluded (e.g., by acute angulation). Failure of any urine to appear from one of the orifices highly suggests injury to that ureter.

During inspection of the operative field, attempt to pass a ureteral stent into the affected orifice. If the stent passes easily and dyed urine is seen to drip freely from it, look for possible angulation of the ureter. If you find none, remove the stent and inspect the orifice again for jetting urine.

If the ureteral stent will move only a few centimeters into the ureteral orifice, ligation (with or without transection) is likely. In this case, leave the stent in place. If the operative site is readily accessible, dissect the applicable area to identify the problem. Depending on the circumstances, you may wish to infuse dye through the stent to aid in operative identification or radiographic evaluation.

Intraoperative IVP may be useful, especially when cystoscopy is unavailable.

Fundamentals of repair

Repair of major injury to the pelvic ureter is generally best accomplished by ureteroneocystostomy or, in selected cases involving injury to the proximal pelvic ureter, by ureteroureterostomy.

When intraoperatively recognized injury to the pelvic ureter appears to be minor, it can be managed by placing a ureteral stent and a closed-suction pelvic drain. Also consider wrapping the injured area with vascularized tissue such as perivesical fat. Minor lacerations can be closed perpendicular to the axis of the ureter using interrupted 4-0 delayed absorbable suture.

Most injuries to the pelvic ureter are optimally managed by ureteroneocystostomy (FIGURE 3). When a significant portion of the pelvic ureter has been lost, ureteroneocystostomy usually requires a combination of:

- extensive mobilization of the bladder

- conservative mobilization of the ureter

- elongation of the bladder

- psoas hitch.

When necessary, mobilization of the kidney with suturing of the caudal perinephric fascia to the psoas muscle will bridge an additional 2- to 3-cm gap.

Major injury to the distal half of the pelvic ureter is repaired using straightforward ureteroneocystostomy.

When there is no significant pelvic disease and the distal ureter is healthy, injury to the proximal pelvic ureter during division of the ovarian vessels may be repaired via ureteroureterostomy. If the ureteral ends will be anastomosed on tension or there is any question about the integrity of the distal portion of the ureter, as when extensive distal ureterolysis has been necessary, consider ureteroneocystostomy.

FIGURE 3 When the distal ureter is injured

Most injuries to the pelvic ureter are managed optimally by ureteroneocystostomy.

Ureter injured during emergent hysterectomy

A 37-year-old woman, para 4, undergoes her fourth repeat cesarean section. When the OB attempts to manually extract the placenta, the patient begins to hemorrhage profusely. Conservative measures fail to stop the bleeding, and the patient becomes hypotensive. The physician performs emergent hysterectomy, taking large pedicles of tissue. Although the patient stabilizes, the doctor worries that the ureters may have been injured.

Resolution: Cystoscopy is performed to check for injury. Because indigo carmine does not spill from the left ureteral orifice, the physician passes a stent with the abdomen still open, and it stops within the most distal ligamentous pedicle. Upon deligation, indigo carmine begins to drain from the stent, which then passes easily.

The stent is withdrawn to below the site of injury, and dilute methylene blue is instilled through it while the ureter is observed under irrigation. No extravasation is noted. Because the ligature had been around a block of tissue that was thought to have acutely angulated rather than incorporated the ureter, the physician concludes that severe damage is unlikely. He places a 6 French double-J stent, wraps the damaged portion of the distal ureter in perivesical fat, and places a closed-suction pelvic drain. Healing is uneventful.

Obstruction is confirmed. Now the surgeon must find it

A 45-year-old woman, para 3, who has a symptomatic 14-weeks’ size myomatous uterus, undergoes vaginal hysterectomy. The surgeon ligates and divides the uterine vessel pedicles before beginning morcellation. At the completion of the procedure, during cystoscopy, indigo carmine fails to spill from the right ureteral orifice, suggesting injury to that ureter. The surgeon passes a stent into the ureter, and it stops approximately 6 cm from the orifice. A retrograde pyelogram confirms complete obstruction.

Resolution: With the stent left in place, the surgeon performs a midline laparotomy, tracing the ureter to the uterine artery pedicle in which it has been incorporated and transected. The distal ureter with the stent is found within soft tissue lateral to the cardinal ligament pedicle, and the transected end is securely ligated using 2–0 silk suture. After the bladder is mobilized, a ureteroneocystostomy is performed. The patient recovers fully.

Postoperative management

After repair of a ureteral injury, leave a closed-suction pelvic drain in place for 2 to 3 days so that any major urinary leak can be detected; it also enhances spontaneous closure and helps prevent potentially infected fluid from accumulating in the region of anastomosis.

The cystotomy performed during ureteroneocystostomy generally heals quickly with a low risk of complications.

Leave a large-bore (20 or 22 French) urethral Foley catheter in place for 2 weeks.

I recommend that a 6 French double-J ureteral stent be left in place for 6 weeks. Potential benefits of the stent include:

- prevention of stricture

- stabilization and immobilization of the ureter during healing

- reduced risk of extravasation of urine

- reduced risk of angulation of the ureter

- isolation of the repair from infection, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and cancer.

I perform IVP approximately 1 week after stent removal to ensure ureteral patency.

CASE RESOLVED

Exposure is improved by widening the incision and dividing the tendonous insertions of the rectus abdominus muscles. The surgeon then removes the mass, preserving the distal ureter, which is estimated to be 12 cm in length and to have intact adventitia.

The surgeon performs a double-spatulated end-to-end ureteroureterostomy over a 6 French double-J ureteral stent that has been passed proximally into the renal pelvis and distally into the bladder. The stent is removed 6 weeks postoperatively, and an IVP the following week demonstrates excellent patency.

The majority of payers consider ureterolysis integral to good surgical technique, but there can be exceptions when documentation supports existing codes. Three CPT codes describe this procedure:

50715 Ureterolysis, with or without repositioning of ureter for retroperitoneal fibrosis

50722 Ureterolysis for ovarian vein syndrome

50725 Ureterolysis for retrocaval ureter, with reanastomosis of upper urinary tract or vena cava

The key to getting paid will be to document the existence of the condition indicated by each of the codes.

The ICD-9 code for both retroperitoneal fibrosis and ovarian vein syndrome is the same, 593.4 (Other ureteric obstruction). If the patient requires ureterolysis for a retrocaval ureter, the code 753.4 (Other specified anomalies of ureter) would be reported instead. Note, however, that these procedure codes cannot be reported if the ureterolysis is performed laparoscopically. In that case, the most appropriate code is 50949 (Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, ureter).

When repair is necessary, you have several codes to choose from, but the supporting diagnosis code 998.2 (Accidental puncture or laceration during a procedure) must be indicated. If a Medicare patient is involved, the surgeon who created the injury would not be paid additionally for repair.

50780 Ureteroneocystostomy; anastomosis of single ureter to bladder

50782 Ureteroneocystostomy; anastomosis of duplicated ureter to bladder

50783 Ureteroneocystostomy; with extensive ureteral tailoring

50785 Ureteroneocystostomy; with vesico-psoas hitch or bladder flap

50760 Ureteroureterostomy; fusion of ureters

50770 Transureteroureterostomy, anastomosis of ureter to contralateral ureter—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC-OBGYN, MA

1. St. Lezin MA, Stoller ML. Surgical ureteral injuries. Urology. 1991;38:497-506.

2. Liapis A, Bakas P, Giannopoulos V, Creatsas G. Ureteral injuries during gynecological surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:391-394.

3. Vakili B, Chesson RR, Kyle BL, et al. The incidence of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy: a prospective analysis based on universal cystoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1599-1604.

4. Sakellariou P, Protopapas AG, Voulgaris Z, et al. Management of ureteric injuries during gynecological operations: 10 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;101:179-184.

5. Assimos DG, Patterson LC, Taylor CL. Changing incidence and etiology of iatrogenic ureteral injuries. J Urol. 1994;152:2240-2246.

6. Härkki-Sirén P, Sjöberg J, Titinen A. Urinary tract injuries after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:113-118.

7. Chan JK, Morrow J, Manetta A. Prevention of ureteral injuries in gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1273-1277.

The author has no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Inadvertent ureteral transection

A gynecologic surgeon operates via Pfannenstiel incision to remove a 12-cm complex left adnexal mass from a 36-year-old obese woman. When she discovers that the mass is densely adherent to the pelvic peritoneum, the surgeon incises the peritoneum lateral to the mass and opens the retroperitoneal space. However, the size and relative immobility of the mass, coupled with the low transverse incision, impair visualization of retroperitoneal structures.

The surgeon clamps and divides the ovarian vessels above the mass but, afterward, suspects that the ureter has been transected and that its ends are included within the clamps. She separates the ovarian vessels above the clamp and ligates them, at which time transection of the ureter is confirmed.

How should she proceed?

The ureter is intimately associated with the female internal genitalia in a way that challenges the gynecologic surgeon to avoid it. In a small percentage of cases involving surgical extirpation in a woman who has severe pelvic pathology, ureteral injury may be inevitable.

Several variables predispose a patient to ureteral injury, including limited exposure, as in the opening case. Others include distorted anatomy of the urinary tract relative to internal genitalia and operations that require extensive resection of pelvic tissues.

This article describes:

- prevention and intraoperative recognition of ureteral injury during gynecologic surgery

- management of intraoperatively recognized ureteral injury.

Maintain a high index of suspicion

The surgeon in the opening case has already taken the first and most important step in ensuring a good outcome: She suspected ureteral injury. In high-risk situations, intraoperative recognition of ureteral injury is more likely when the operative field is inspected thoroughly during and at the conclusion of the surgical procedure.

In a high-risk case, the combined use of intravenous indigo carmine, careful inspection of the operative field, cystoscopy, and ureteral dissection is recommended and should be routine.

Common sites of injury

During gynecologic surgery, the ureter is susceptible to injury along its entire course through the pelvis (see “The ureter takes a course fraught with hazard,”).

During adnexectomy, the gonadal vessels are generally ligated 2 to 3 cm above the adnexa. The ureter lies in close proximity to these vessels and may inadvertently be included in the ligation.

During hysterectomy, the ureter is susceptible to injury as it passes through the parametrium a short distance from the uterus and vaginal fornix.

Sutures placed in the posterior lateral cul de sac during prolapse surgery lie near the midpelvic ureter, and sutures placed during vaginal cuff closure, anterior colporrhaphy, and retropubic urethropexy are in close proximity to the trigonal portion of the ureter.

The ureter extends from the renal pelvis to the bladder, with a length that ranges from 25 to 30 cm, depending on the patient’s height. It crosses the pelvic brim near the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, where it becomes the “pelvic” ureter. The abdominal and pelvic portions of the ureter are approximately equal in length.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ROB FLEWELL FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

The blood supply of the ureter derives from branches of the major arterial system of the lower abdomen and pelvis. These branches reach the medial aspect of the abdominal ureter and the lateral side of the pelvic ureter to form an anastomotic vascular network protected by an adventitial layer surrounding the ureter.

The ureter is attached to the posterior lateral pelvic peritoneum running dorsal to ovarian vessels. At the midpelvis, it separates from the peritoneum to pierce the base of the broad ligament underneath the uterine artery. At this point, the ureter is about 1.5 to 2 cm lateral to the uterus and curves medially and ventrally, tunneling through the cardinal and vesicovaginal ligaments to enter the bladder trigone.

Risky procedures

In gynecologic surgery, ureteral injury occurs most often during abdominal hysterectomy—probably because of how frequently this operation is performed and the range of pathology managed. The incidence of ureteral injury is much higher during abdominal hysterectomy than vaginal hysterectomy.1-4

Laparoscopic hysterectomy also has been associated with a higher incidence of ureteral injury, especially in the early phase of training.5,6 Possible explanations include:

- greater difficulty identifying the ureter

- a steeper learning curve

- more frequent use of energy to hemostatically divide pedicles, with the potential for thermal injury

- less traction–countertraction, resulting in dissection closer to the ureter

- management of complex pathology.

Although the overall incidence of ureteral injury during adnexectomy is low, it is probably much higher in women undergoing this procedure after a previous hysterectomy or in the presence of complex adnexal pathology.

When injury is likely

Compromised exposure, distorted anatomy, and certain procedures can heighten the risk of ureteral injury. Large tumors may limit the ability of the surgeon to visualize or palpate the ureter (FIGURE 1). Extensive adhesions may cause similar difficulties, and a small incision or obesity may hinder identification of pelvic sidewall structures.

A number of pathologic conditions can distort the anatomy of the ureter, especially as it relates to the female genital tract:

- Malignancies such as ovarian cancer often encroach on and occasionally encase the ureter

- Pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, and a history of surgery or pelvic radiotherapy can retract and encase the ureter toward the gynecologic tract

- Some masses expand against the lower ureter, such as cervical or broad-ligament leiomyomata or placenta previa with accreta

- During vaginal hysterectomy for complete uterine prolapse, the ureters frequently extend beyond the introitus well within the operative field

- Congenital anomalies of the ureter or hydroureter can also cause distortion.

Even in the presence of relatively normal anatomy, certain procedures predispose the ureter to injury. For example, radical hysterectomy involves the almost complete separation of the pelvic ureter from the gynecologic tract and its surrounding soft tissue. When pelvic pathology is significant, the plane of dissection will always be near the ureter.

FIGURE 1 Access to the ureter is obstructed, putting it in jeopardy

Large tumors may limit the ability of the surgeon to visualize or palpate the ureter.

Prevention is the best strategy

At least 50% of ureteral injuries reported during gynecologic surgery have occurred in the absence of a recognizable risk factor.2,7 Nevertheless, knowledge of anatomy and the ability to recognize situations in which there is an elevated risk for ureteral injury will best enable the surgeon to prevent such injury.

When a high-risk situation is encountered, critical preventive steps include:

- adequate exposure

- competent assistance

- exposure of the path of the ureter through the planned course of dissection. Dissecting the ureter beyond this area is usually unnecessary and may itself cause injury.

Skip preoperative IVP in most cases

The vast majority of women who undergo gynecologic surgery do not benefit from preoperative intravenous pyelography (IVP). This measure does not appear to reduce the likelihood of ureteral injury, even in the face of obvious gynecologic disease. However, preoperative identification of obvious ureteral involvement by the disease process is useful. In such cases, the plane of dissection will probably lie closer to the ureter. One of the goals of surgery will then be to clear the urinary tract from the affected area.

When there is a high index of suspicion of an abnormality such as obstruction, intrinsic ureteral endometriosis, or congenital anomaly, preoperative IVP is indicated.

A stent may be helpful in some cases

Ureteral stents are sometimes placed in order to aid in identification and dissection of the ureters during surgery. Some authors of reports on this topic, including Hoffman, believe that stents are useful in certain situations, such as excision of an ovarian remnant, radical vaginal hysterectomy, and when pelvic organs are encased by malignant ovarian tumors. However, stents do not clearly reduce the risk of injury and, in some cases, may increase the risk by providing a false sense of security and predisposing the ureter to adventitial injury during difficult dissection.

Anticipate the effects of disease

The surgeon must have a thorough knowledge of the gynecologic disease process as it relates to surgery involving the urinary tract. For example, an ovarian remnant will almost always be somewhat densely adherent to the pelvic ureter. When severe endometriosis involves the posterior leaf of the broad ligament, the ureter will often be fibrotically retracted toward the operative field.

Certain procedures have special challenges. During resection of adnexa, for example, it is important that the ureter be identified in the retroperitoneum before the ovarian vessels are ligated. During hysterectomy, soft tissues that contain the bladder and ureters should be mobilized caudally and laterally, respectively, creating a U-shaped region (“U” for urinary tract, FIGURE 2) to which the surgeon must limit dissection.

FIGURE 2 During hysterectomy, mobilize the bladder and ureter

Mobilize the soft tissues that contain the bladder and ureters caudally and laterally, respectively, creating a U-shaped region. During division of the paracervical tissues, the surgeon must remain within this region.

Intraoperative detection

Two main types of ureteral injury occur during gynecologic surgery: transection and destruction. The latter includes ligation, crushing, devascularization, and thermal injury.

Intraoperative detection of ureteral injury is more likely when the surgeon recognizes at the outset that the operation places the ureter at increased risk. When dissection has been difficult or complicated for any reason, be concerned about possible injury.

In general, ureteral injury is first recognized by careful inspection of the surgical field. Begin by instilling 5 ml of indigo carmine intravenously. Once the dye begins to appear in the Foley catheter, inspect the area of dissection under a small amount of irrigation fluid, looking for extravasation of dye that indicates partial or complete transection.

If no injury is identified, cystoscopy is the next step. I perform all major abdominal operations with the patient in the low lithotomy position, which provides easy access to the perineum. Cystoscopic identification of urine jetting from both ureteral orifices confirms patency. When only wisps of dye are observed, it is likely that the ureter in question has been partially occluded (e.g., by acute angulation). Failure of any urine to appear from one of the orifices highly suggests injury to that ureter.

During inspection of the operative field, attempt to pass a ureteral stent into the affected orifice. If the stent passes easily and dyed urine is seen to drip freely from it, look for possible angulation of the ureter. If you find none, remove the stent and inspect the orifice again for jetting urine.

If the ureteral stent will move only a few centimeters into the ureteral orifice, ligation (with or without transection) is likely. In this case, leave the stent in place. If the operative site is readily accessible, dissect the applicable area to identify the problem. Depending on the circumstances, you may wish to infuse dye through the stent to aid in operative identification or radiographic evaluation.

Intraoperative IVP may be useful, especially when cystoscopy is unavailable.

Fundamentals of repair

Repair of major injury to the pelvic ureter is generally best accomplished by ureteroneocystostomy or, in selected cases involving injury to the proximal pelvic ureter, by ureteroureterostomy.

When intraoperatively recognized injury to the pelvic ureter appears to be minor, it can be managed by placing a ureteral stent and a closed-suction pelvic drain. Also consider wrapping the injured area with vascularized tissue such as perivesical fat. Minor lacerations can be closed perpendicular to the axis of the ureter using interrupted 4-0 delayed absorbable suture.

Most injuries to the pelvic ureter are optimally managed by ureteroneocystostomy (FIGURE 3). When a significant portion of the pelvic ureter has been lost, ureteroneocystostomy usually requires a combination of:

- extensive mobilization of the bladder

- conservative mobilization of the ureter

- elongation of the bladder

- psoas hitch.

When necessary, mobilization of the kidney with suturing of the caudal perinephric fascia to the psoas muscle will bridge an additional 2- to 3-cm gap.

Major injury to the distal half of the pelvic ureter is repaired using straightforward ureteroneocystostomy.

When there is no significant pelvic disease and the distal ureter is healthy, injury to the proximal pelvic ureter during division of the ovarian vessels may be repaired via ureteroureterostomy. If the ureteral ends will be anastomosed on tension or there is any question about the integrity of the distal portion of the ureter, as when extensive distal ureterolysis has been necessary, consider ureteroneocystostomy.

FIGURE 3 When the distal ureter is injured

Most injuries to the pelvic ureter are managed optimally by ureteroneocystostomy.

Ureter injured during emergent hysterectomy

A 37-year-old woman, para 4, undergoes her fourth repeat cesarean section. When the OB attempts to manually extract the placenta, the patient begins to hemorrhage profusely. Conservative measures fail to stop the bleeding, and the patient becomes hypotensive. The physician performs emergent hysterectomy, taking large pedicles of tissue. Although the patient stabilizes, the doctor worries that the ureters may have been injured.

Resolution: Cystoscopy is performed to check for injury. Because indigo carmine does not spill from the left ureteral orifice, the physician passes a stent with the abdomen still open, and it stops within the most distal ligamentous pedicle. Upon deligation, indigo carmine begins to drain from the stent, which then passes easily.

The stent is withdrawn to below the site of injury, and dilute methylene blue is instilled through it while the ureter is observed under irrigation. No extravasation is noted. Because the ligature had been around a block of tissue that was thought to have acutely angulated rather than incorporated the ureter, the physician concludes that severe damage is unlikely. He places a 6 French double-J stent, wraps the damaged portion of the distal ureter in perivesical fat, and places a closed-suction pelvic drain. Healing is uneventful.

Obstruction is confirmed. Now the surgeon must find it

A 45-year-old woman, para 3, who has a symptomatic 14-weeks’ size myomatous uterus, undergoes vaginal hysterectomy. The surgeon ligates and divides the uterine vessel pedicles before beginning morcellation. At the completion of the procedure, during cystoscopy, indigo carmine fails to spill from the right ureteral orifice, suggesting injury to that ureter. The surgeon passes a stent into the ureter, and it stops approximately 6 cm from the orifice. A retrograde pyelogram confirms complete obstruction.

Resolution: With the stent left in place, the surgeon performs a midline laparotomy, tracing the ureter to the uterine artery pedicle in which it has been incorporated and transected. The distal ureter with the stent is found within soft tissue lateral to the cardinal ligament pedicle, and the transected end is securely ligated using 2–0 silk suture. After the bladder is mobilized, a ureteroneocystostomy is performed. The patient recovers fully.

Postoperative management

After repair of a ureteral injury, leave a closed-suction pelvic drain in place for 2 to 3 days so that any major urinary leak can be detected; it also enhances spontaneous closure and helps prevent potentially infected fluid from accumulating in the region of anastomosis.

The cystotomy performed during ureteroneocystostomy generally heals quickly with a low risk of complications.

Leave a large-bore (20 or 22 French) urethral Foley catheter in place for 2 weeks.

I recommend that a 6 French double-J ureteral stent be left in place for 6 weeks. Potential benefits of the stent include:

- prevention of stricture

- stabilization and immobilization of the ureter during healing

- reduced risk of extravasation of urine

- reduced risk of angulation of the ureter

- isolation of the repair from infection, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and cancer.

I perform IVP approximately 1 week after stent removal to ensure ureteral patency.

CASE RESOLVED

Exposure is improved by widening the incision and dividing the tendonous insertions of the rectus abdominus muscles. The surgeon then removes the mass, preserving the distal ureter, which is estimated to be 12 cm in length and to have intact adventitia.

The surgeon performs a double-spatulated end-to-end ureteroureterostomy over a 6 French double-J ureteral stent that has been passed proximally into the renal pelvis and distally into the bladder. The stent is removed 6 weeks postoperatively, and an IVP the following week demonstrates excellent patency.

The majority of payers consider ureterolysis integral to good surgical technique, but there can be exceptions when documentation supports existing codes. Three CPT codes describe this procedure:

50715 Ureterolysis, with or without repositioning of ureter for retroperitoneal fibrosis

50722 Ureterolysis for ovarian vein syndrome

50725 Ureterolysis for retrocaval ureter, with reanastomosis of upper urinary tract or vena cava

The key to getting paid will be to document the existence of the condition indicated by each of the codes.

The ICD-9 code for both retroperitoneal fibrosis and ovarian vein syndrome is the same, 593.4 (Other ureteric obstruction). If the patient requires ureterolysis for a retrocaval ureter, the code 753.4 (Other specified anomalies of ureter) would be reported instead. Note, however, that these procedure codes cannot be reported if the ureterolysis is performed laparoscopically. In that case, the most appropriate code is 50949 (Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, ureter).

When repair is necessary, you have several codes to choose from, but the supporting diagnosis code 998.2 (Accidental puncture or laceration during a procedure) must be indicated. If a Medicare patient is involved, the surgeon who created the injury would not be paid additionally for repair.

50780 Ureteroneocystostomy; anastomosis of single ureter to bladder

50782 Ureteroneocystostomy; anastomosis of duplicated ureter to bladder

50783 Ureteroneocystostomy; with extensive ureteral tailoring

50785 Ureteroneocystostomy; with vesico-psoas hitch or bladder flap

50760 Ureteroureterostomy; fusion of ureters

50770 Transureteroureterostomy, anastomosis of ureter to contralateral ureter—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC-OBGYN, MA

The author has no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE: Inadvertent ureteral transection

A gynecologic surgeon operates via Pfannenstiel incision to remove a 12-cm complex left adnexal mass from a 36-year-old obese woman. When she discovers that the mass is densely adherent to the pelvic peritoneum, the surgeon incises the peritoneum lateral to the mass and opens the retroperitoneal space. However, the size and relative immobility of the mass, coupled with the low transverse incision, impair visualization of retroperitoneal structures.

The surgeon clamps and divides the ovarian vessels above the mass but, afterward, suspects that the ureter has been transected and that its ends are included within the clamps. She separates the ovarian vessels above the clamp and ligates them, at which time transection of the ureter is confirmed.

How should she proceed?

The ureter is intimately associated with the female internal genitalia in a way that challenges the gynecologic surgeon to avoid it. In a small percentage of cases involving surgical extirpation in a woman who has severe pelvic pathology, ureteral injury may be inevitable.

Several variables predispose a patient to ureteral injury, including limited exposure, as in the opening case. Others include distorted anatomy of the urinary tract relative to internal genitalia and operations that require extensive resection of pelvic tissues.

This article describes:

- prevention and intraoperative recognition of ureteral injury during gynecologic surgery

- management of intraoperatively recognized ureteral injury.

Maintain a high index of suspicion

The surgeon in the opening case has already taken the first and most important step in ensuring a good outcome: She suspected ureteral injury. In high-risk situations, intraoperative recognition of ureteral injury is more likely when the operative field is inspected thoroughly during and at the conclusion of the surgical procedure.

In a high-risk case, the combined use of intravenous indigo carmine, careful inspection of the operative field, cystoscopy, and ureteral dissection is recommended and should be routine.

Common sites of injury

During gynecologic surgery, the ureter is susceptible to injury along its entire course through the pelvis (see “The ureter takes a course fraught with hazard,”).

During adnexectomy, the gonadal vessels are generally ligated 2 to 3 cm above the adnexa. The ureter lies in close proximity to these vessels and may inadvertently be included in the ligation.

During hysterectomy, the ureter is susceptible to injury as it passes through the parametrium a short distance from the uterus and vaginal fornix.

Sutures placed in the posterior lateral cul de sac during prolapse surgery lie near the midpelvic ureter, and sutures placed during vaginal cuff closure, anterior colporrhaphy, and retropubic urethropexy are in close proximity to the trigonal portion of the ureter.

The ureter extends from the renal pelvis to the bladder, with a length that ranges from 25 to 30 cm, depending on the patient’s height. It crosses the pelvic brim near the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, where it becomes the “pelvic” ureter. The abdominal and pelvic portions of the ureter are approximately equal in length.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ROB FLEWELL FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

The blood supply of the ureter derives from branches of the major arterial system of the lower abdomen and pelvis. These branches reach the medial aspect of the abdominal ureter and the lateral side of the pelvic ureter to form an anastomotic vascular network protected by an adventitial layer surrounding the ureter.

The ureter is attached to the posterior lateral pelvic peritoneum running dorsal to ovarian vessels. At the midpelvis, it separates from the peritoneum to pierce the base of the broad ligament underneath the uterine artery. At this point, the ureter is about 1.5 to 2 cm lateral to the uterus and curves medially and ventrally, tunneling through the cardinal and vesicovaginal ligaments to enter the bladder trigone.

Risky procedures

In gynecologic surgery, ureteral injury occurs most often during abdominal hysterectomy—probably because of how frequently this operation is performed and the range of pathology managed. The incidence of ureteral injury is much higher during abdominal hysterectomy than vaginal hysterectomy.1-4

Laparoscopic hysterectomy also has been associated with a higher incidence of ureteral injury, especially in the early phase of training.5,6 Possible explanations include:

- greater difficulty identifying the ureter

- a steeper learning curve

- more frequent use of energy to hemostatically divide pedicles, with the potential for thermal injury

- less traction–countertraction, resulting in dissection closer to the ureter

- management of complex pathology.

Although the overall incidence of ureteral injury during adnexectomy is low, it is probably much higher in women undergoing this procedure after a previous hysterectomy or in the presence of complex adnexal pathology.

When injury is likely

Compromised exposure, distorted anatomy, and certain procedures can heighten the risk of ureteral injury. Large tumors may limit the ability of the surgeon to visualize or palpate the ureter (FIGURE 1). Extensive adhesions may cause similar difficulties, and a small incision or obesity may hinder identification of pelvic sidewall structures.

A number of pathologic conditions can distort the anatomy of the ureter, especially as it relates to the female genital tract:

- Malignancies such as ovarian cancer often encroach on and occasionally encase the ureter

- Pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, and a history of surgery or pelvic radiotherapy can retract and encase the ureter toward the gynecologic tract

- Some masses expand against the lower ureter, such as cervical or broad-ligament leiomyomata or placenta previa with accreta

- During vaginal hysterectomy for complete uterine prolapse, the ureters frequently extend beyond the introitus well within the operative field

- Congenital anomalies of the ureter or hydroureter can also cause distortion.

Even in the presence of relatively normal anatomy, certain procedures predispose the ureter to injury. For example, radical hysterectomy involves the almost complete separation of the pelvic ureter from the gynecologic tract and its surrounding soft tissue. When pelvic pathology is significant, the plane of dissection will always be near the ureter.

FIGURE 1 Access to the ureter is obstructed, putting it in jeopardy

Large tumors may limit the ability of the surgeon to visualize or palpate the ureter.

Prevention is the best strategy

At least 50% of ureteral injuries reported during gynecologic surgery have occurred in the absence of a recognizable risk factor.2,7 Nevertheless, knowledge of anatomy and the ability to recognize situations in which there is an elevated risk for ureteral injury will best enable the surgeon to prevent such injury.

When a high-risk situation is encountered, critical preventive steps include:

- adequate exposure

- competent assistance

- exposure of the path of the ureter through the planned course of dissection. Dissecting the ureter beyond this area is usually unnecessary and may itself cause injury.

Skip preoperative IVP in most cases

The vast majority of women who undergo gynecologic surgery do not benefit from preoperative intravenous pyelography (IVP). This measure does not appear to reduce the likelihood of ureteral injury, even in the face of obvious gynecologic disease. However, preoperative identification of obvious ureteral involvement by the disease process is useful. In such cases, the plane of dissection will probably lie closer to the ureter. One of the goals of surgery will then be to clear the urinary tract from the affected area.

When there is a high index of suspicion of an abnormality such as obstruction, intrinsic ureteral endometriosis, or congenital anomaly, preoperative IVP is indicated.

A stent may be helpful in some cases

Ureteral stents are sometimes placed in order to aid in identification and dissection of the ureters during surgery. Some authors of reports on this topic, including Hoffman, believe that stents are useful in certain situations, such as excision of an ovarian remnant, radical vaginal hysterectomy, and when pelvic organs are encased by malignant ovarian tumors. However, stents do not clearly reduce the risk of injury and, in some cases, may increase the risk by providing a false sense of security and predisposing the ureter to adventitial injury during difficult dissection.

Anticipate the effects of disease

The surgeon must have a thorough knowledge of the gynecologic disease process as it relates to surgery involving the urinary tract. For example, an ovarian remnant will almost always be somewhat densely adherent to the pelvic ureter. When severe endometriosis involves the posterior leaf of the broad ligament, the ureter will often be fibrotically retracted toward the operative field.

Certain procedures have special challenges. During resection of adnexa, for example, it is important that the ureter be identified in the retroperitoneum before the ovarian vessels are ligated. During hysterectomy, soft tissues that contain the bladder and ureters should be mobilized caudally and laterally, respectively, creating a U-shaped region (“U” for urinary tract, FIGURE 2) to which the surgeon must limit dissection.

FIGURE 2 During hysterectomy, mobilize the bladder and ureter

Mobilize the soft tissues that contain the bladder and ureters caudally and laterally, respectively, creating a U-shaped region. During division of the paracervical tissues, the surgeon must remain within this region.

Intraoperative detection

Two main types of ureteral injury occur during gynecologic surgery: transection and destruction. The latter includes ligation, crushing, devascularization, and thermal injury.

Intraoperative detection of ureteral injury is more likely when the surgeon recognizes at the outset that the operation places the ureter at increased risk. When dissection has been difficult or complicated for any reason, be concerned about possible injury.

In general, ureteral injury is first recognized by careful inspection of the surgical field. Begin by instilling 5 ml of indigo carmine intravenously. Once the dye begins to appear in the Foley catheter, inspect the area of dissection under a small amount of irrigation fluid, looking for extravasation of dye that indicates partial or complete transection.

If no injury is identified, cystoscopy is the next step. I perform all major abdominal operations with the patient in the low lithotomy position, which provides easy access to the perineum. Cystoscopic identification of urine jetting from both ureteral orifices confirms patency. When only wisps of dye are observed, it is likely that the ureter in question has been partially occluded (e.g., by acute angulation). Failure of any urine to appear from one of the orifices highly suggests injury to that ureter.

During inspection of the operative field, attempt to pass a ureteral stent into the affected orifice. If the stent passes easily and dyed urine is seen to drip freely from it, look for possible angulation of the ureter. If you find none, remove the stent and inspect the orifice again for jetting urine.

If the ureteral stent will move only a few centimeters into the ureteral orifice, ligation (with or without transection) is likely. In this case, leave the stent in place. If the operative site is readily accessible, dissect the applicable area to identify the problem. Depending on the circumstances, you may wish to infuse dye through the stent to aid in operative identification or radiographic evaluation.

Intraoperative IVP may be useful, especially when cystoscopy is unavailable.

Fundamentals of repair

Repair of major injury to the pelvic ureter is generally best accomplished by ureteroneocystostomy or, in selected cases involving injury to the proximal pelvic ureter, by ureteroureterostomy.

When intraoperatively recognized injury to the pelvic ureter appears to be minor, it can be managed by placing a ureteral stent and a closed-suction pelvic drain. Also consider wrapping the injured area with vascularized tissue such as perivesical fat. Minor lacerations can be closed perpendicular to the axis of the ureter using interrupted 4-0 delayed absorbable suture.

Most injuries to the pelvic ureter are optimally managed by ureteroneocystostomy (FIGURE 3). When a significant portion of the pelvic ureter has been lost, ureteroneocystostomy usually requires a combination of:

- extensive mobilization of the bladder

- conservative mobilization of the ureter

- elongation of the bladder

- psoas hitch.

When necessary, mobilization of the kidney with suturing of the caudal perinephric fascia to the psoas muscle will bridge an additional 2- to 3-cm gap.

Major injury to the distal half of the pelvic ureter is repaired using straightforward ureteroneocystostomy.

When there is no significant pelvic disease and the distal ureter is healthy, injury to the proximal pelvic ureter during division of the ovarian vessels may be repaired via ureteroureterostomy. If the ureteral ends will be anastomosed on tension or there is any question about the integrity of the distal portion of the ureter, as when extensive distal ureterolysis has been necessary, consider ureteroneocystostomy.

FIGURE 3 When the distal ureter is injured

Most injuries to the pelvic ureter are managed optimally by ureteroneocystostomy.

Ureter injured during emergent hysterectomy

A 37-year-old woman, para 4, undergoes her fourth repeat cesarean section. When the OB attempts to manually extract the placenta, the patient begins to hemorrhage profusely. Conservative measures fail to stop the bleeding, and the patient becomes hypotensive. The physician performs emergent hysterectomy, taking large pedicles of tissue. Although the patient stabilizes, the doctor worries that the ureters may have been injured.

Resolution: Cystoscopy is performed to check for injury. Because indigo carmine does not spill from the left ureteral orifice, the physician passes a stent with the abdomen still open, and it stops within the most distal ligamentous pedicle. Upon deligation, indigo carmine begins to drain from the stent, which then passes easily.

The stent is withdrawn to below the site of injury, and dilute methylene blue is instilled through it while the ureter is observed under irrigation. No extravasation is noted. Because the ligature had been around a block of tissue that was thought to have acutely angulated rather than incorporated the ureter, the physician concludes that severe damage is unlikely. He places a 6 French double-J stent, wraps the damaged portion of the distal ureter in perivesical fat, and places a closed-suction pelvic drain. Healing is uneventful.

Obstruction is confirmed. Now the surgeon must find it

A 45-year-old woman, para 3, who has a symptomatic 14-weeks’ size myomatous uterus, undergoes vaginal hysterectomy. The surgeon ligates and divides the uterine vessel pedicles before beginning morcellation. At the completion of the procedure, during cystoscopy, indigo carmine fails to spill from the right ureteral orifice, suggesting injury to that ureter. The surgeon passes a stent into the ureter, and it stops approximately 6 cm from the orifice. A retrograde pyelogram confirms complete obstruction.

Resolution: With the stent left in place, the surgeon performs a midline laparotomy, tracing the ureter to the uterine artery pedicle in which it has been incorporated and transected. The distal ureter with the stent is found within soft tissue lateral to the cardinal ligament pedicle, and the transected end is securely ligated using 2–0 silk suture. After the bladder is mobilized, a ureteroneocystostomy is performed. The patient recovers fully.

Postoperative management

After repair of a ureteral injury, leave a closed-suction pelvic drain in place for 2 to 3 days so that any major urinary leak can be detected; it also enhances spontaneous closure and helps prevent potentially infected fluid from accumulating in the region of anastomosis.

The cystotomy performed during ureteroneocystostomy generally heals quickly with a low risk of complications.

Leave a large-bore (20 or 22 French) urethral Foley catheter in place for 2 weeks.

I recommend that a 6 French double-J ureteral stent be left in place for 6 weeks. Potential benefits of the stent include:

- prevention of stricture

- stabilization and immobilization of the ureter during healing

- reduced risk of extravasation of urine

- reduced risk of angulation of the ureter

- isolation of the repair from infection, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and cancer.

I perform IVP approximately 1 week after stent removal to ensure ureteral patency.

CASE RESOLVED

Exposure is improved by widening the incision and dividing the tendonous insertions of the rectus abdominus muscles. The surgeon then removes the mass, preserving the distal ureter, which is estimated to be 12 cm in length and to have intact adventitia.

The surgeon performs a double-spatulated end-to-end ureteroureterostomy over a 6 French double-J ureteral stent that has been passed proximally into the renal pelvis and distally into the bladder. The stent is removed 6 weeks postoperatively, and an IVP the following week demonstrates excellent patency.

The majority of payers consider ureterolysis integral to good surgical technique, but there can be exceptions when documentation supports existing codes. Three CPT codes describe this procedure:

50715 Ureterolysis, with or without repositioning of ureter for retroperitoneal fibrosis

50722 Ureterolysis for ovarian vein syndrome

50725 Ureterolysis for retrocaval ureter, with reanastomosis of upper urinary tract or vena cava

The key to getting paid will be to document the existence of the condition indicated by each of the codes.

The ICD-9 code for both retroperitoneal fibrosis and ovarian vein syndrome is the same, 593.4 (Other ureteric obstruction). If the patient requires ureterolysis for a retrocaval ureter, the code 753.4 (Other specified anomalies of ureter) would be reported instead. Note, however, that these procedure codes cannot be reported if the ureterolysis is performed laparoscopically. In that case, the most appropriate code is 50949 (Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, ureter).

When repair is necessary, you have several codes to choose from, but the supporting diagnosis code 998.2 (Accidental puncture or laceration during a procedure) must be indicated. If a Medicare patient is involved, the surgeon who created the injury would not be paid additionally for repair.

50780 Ureteroneocystostomy; anastomosis of single ureter to bladder

50782 Ureteroneocystostomy; anastomosis of duplicated ureter to bladder

50783 Ureteroneocystostomy; with extensive ureteral tailoring

50785 Ureteroneocystostomy; with vesico-psoas hitch or bladder flap

50760 Ureteroureterostomy; fusion of ureters

50770 Transureteroureterostomy, anastomosis of ureter to contralateral ureter—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC-OBGYN, MA

1. St. Lezin MA, Stoller ML. Surgical ureteral injuries. Urology. 1991;38:497-506.

2. Liapis A, Bakas P, Giannopoulos V, Creatsas G. Ureteral injuries during gynecological surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:391-394.

3. Vakili B, Chesson RR, Kyle BL, et al. The incidence of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy: a prospective analysis based on universal cystoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1599-1604.

4. Sakellariou P, Protopapas AG, Voulgaris Z, et al. Management of ureteric injuries during gynecological operations: 10 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;101:179-184.

5. Assimos DG, Patterson LC, Taylor CL. Changing incidence and etiology of iatrogenic ureteral injuries. J Urol. 1994;152:2240-2246.

6. Härkki-Sirén P, Sjöberg J, Titinen A. Urinary tract injuries after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:113-118.

7. Chan JK, Morrow J, Manetta A. Prevention of ureteral injuries in gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1273-1277.

1. St. Lezin MA, Stoller ML. Surgical ureteral injuries. Urology. 1991;38:497-506.

2. Liapis A, Bakas P, Giannopoulos V, Creatsas G. Ureteral injuries during gynecological surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:391-394.

3. Vakili B, Chesson RR, Kyle BL, et al. The incidence of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy: a prospective analysis based on universal cystoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1599-1604.

4. Sakellariou P, Protopapas AG, Voulgaris Z, et al. Management of ureteric injuries during gynecological operations: 10 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;101:179-184.

5. Assimos DG, Patterson LC, Taylor CL. Changing incidence and etiology of iatrogenic ureteral injuries. J Urol. 1994;152:2240-2246.

6. Härkki-Sirén P, Sjöberg J, Titinen A. Urinary tract injuries after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:113-118.

7. Chan JK, Morrow J, Manetta A. Prevention of ureteral injuries in gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1273-1277.

A guide to management: Adnexal masses in pregnancy

CASE 1 An enlarging cystic tumor

A 20-year-old gravida 3 para 1011 visits the emergency department with persistent right flank pain. Although ultrasonography (US) shows a 21-week gestation, the patient has had no prenatal care. Imaging also reveals a right-sided ovarian tumor, 14×11×8 cm, that is mainly cystic with some internal echogenicity.

At 30 weeks’ gestation, a gynecologic oncologist is consulted. Repeat US reveals the mass to be about 20 cm in diameter and cystic, without internal papillation. The patient’s CA-125 level is 12 U/mL. Based on this information, the physicians decide the likely finding is a benign ovarian cystadenoma.

How should they proceed?

The discovery of an adnexal mass during pregnancy isn’t as rare as you might think—depending on when and how closely you look, it occurs in about 1 in 100 gestations. In most cases, we have found, the mass is clearly benign (TABLE 1), warranting only observation.

TABLE 1

Adnexal masses removed during pregnancy: Histologic profile

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| Cystadenoma | 549 (33) |

| Dermoid | 451 (27) |

| Paraovarian/paratubal | 204 (12) |

| Functional | 237 (14) |

| Endometrioma | 55 (3) |

| Benign stromal | 28 (2) |

| Leiomyoma | 23 (1.5) |

| Luteoma | 8 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneous | 55 (3) |

| Malignant | 68 (4) |

| Total | 1,678 |

| Data supplied by the authors from surgical experience | |

In the case described above, the physicians followed the patient and removed the mass at term because it was cystic with no other indications of malignancy. At 37 weeks’ gestation, a cesarean section was performed through a midline laparotomy incision, followed by removal of the ovarian tumor, which was benign. The pathologist measured the tumor at 16×12×4 cm and determined that it was a corpus luteum cyst.

Presence of mass raises questions

Despite the rarity of malignancy, the discovery of an ovarian mass during pregnancy prompts several important questions:

How should the mass be assessed? How can the likelihood of malignancy be determined as quickly and efficiently as possible, without jeopardy to the pregnancy?

When is surgical intervention warranted? And when can it be postponed? Specifically, is elective operative intervention for a tumor that is probably benign appropriate during pregnancy?

When is the best time to operate? And what is the optimal surgical route?

In this article, we address these questions with a focus on intervention. As we’ll explain, only a small percentage of gravidas who have an adnexal mass require surgery during pregnancy. When surgery is necessary, it is usually indicated for an emergent problem or suspicion of malignancy. Even when ovarian cancer is confirmed, we have found that it is usually in its early stages and therefore has a favorable prognosis (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Malignant adnexal masses removed during pregnancy

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| Epithelial | 101 (28) |

| Borderline epithelial | 147 (40) |

| Germ-cell dysgerminoma | 47 (13) |

| Other | 34 (9) |

| Stromal | 24 (7) |

| Undifferentiated | 5 (1.4) |

| Sarcoma | 2 (0.5) |

| Metastatic | 4 (1.1) |

| Total | 364 |

| Data supplied by the authors from surgical experience | |

How should a mass be assessed?

Ultrasonography and other imaging often reveal the presence of a mass and help determine whether it is benign or malignant. In fact, most adnexal masses discovered during pregnancy are incidental findings at the time of routine prenatal US. (see the most commonly found tumors.) Operative intervention is required in 3 situations:

- malignancy is suspected

- an acute complication develops

- the sheer size of the tumor is likely to cause difficulty.

Corpus luteum

A persistent corpus luteum is a normal component of pregnancy. Although it usually appears as a small cystic structure on ultrasonographic imaging, the corpus luteum of pregnancy can reach 10 cm in size. Other types of “functional” ovarian cysts may also be found during pregnancy. Most functional cysts resolve by the early second trimester.4,6 In rare cases, a cyst may develop complications such as torsion or rupture, causing acute pain or hemorrhage. Otherwise, a cystic tumor identified in the first trimester should be characterized and followed using ultrasonography (US).

Benign neoplasm

An adnexal mass that persists beyond the first trimester is more likely to be a neoplasm.3-5,10,11,22 Such a mass is generally considered clinically significant if it exceeds 5 cm in diameter and has a complex sonographic appearance. Usually such a neoplasm will be a benign cystadenoma or cystic teratoma.5,10-13,19,23,24

Benign cystic teratoma

This tumor can be identified with a fairly high degree of specificity using a variety of imaging techniques, with management based on the presumptive diagnosis. This tumor is unlikely to grow substantially during pregnancy. When it is smaller than 6 cm, such a tumor can simply be observed.14 A larger tumor can occasionally rupture or lead to torsion or obstruction of labor, but such occurrences are rare.

Benign cystadenoma

In an asymptomatic patient with imaging that suggests a benign cystadenoma (see sonogram), benign cystic teratoma, or other benign tumor, observation is reasonable in most cases.4,6,7,9-11,14,19 Operative intervention is required when there is less certainty regarding the benign nature of the tumor, an acute complication develops, or the tumor is expected to pose problems because of its large size alone.

Uterine leiomyoma

It is rare for an ovarian tumor detected during pregnancy to have a solid appearance on US. When it does, it may be a uterine leiomyoma mimicking an adnexal tumor (see intraoperative photograph). It should be reevaluated with more detailed US or magnetic resonance imaging.25

Malignancy

About 10% of adnexal masses that persist during pregnancy are malignant, according to recent series.4,5,7-10,12,13,24,26

Most of the ovarian cancers diagnosed during pregnancy are epithelial, and a substantial portion of these are low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumors.5,10,11,13,19,23,24,26,27 This ratio is in keeping with the age of these women, which also explains the stage distribution (most are stage 1) and the large percentage of germ-cell tumors detected. The majority of ovarian cancers discovered in pregnant women have a favorable prognosis.

Benign-appearing cystadenoma

A morphologically benign-appearing, large, cystic adnexal mass can be seen in association with an 11-week gestation.

Leiomyoma mimics an ovarian tumor

This 17-week gestation was marked by a large pedunculated leiomyoma that at fist appeared to be a right adnexal tumor.

Appearance of adnexal masses on US

A functional cyst such as a follicular cyst, corpus luteum cyst, or theca lutein cyst usually has smooth borders and a fluid center. Other cysts may sometimes contain debris, such as clotted blood, that suggests endometriosis or a simple cyst with bleeding into it.

A benign cystic teratoma often has multiple tissue lines, evidence of calcification, and layering of fat and fluid contents.

A benign cystadenoma usually has the appearance of a simple cyst without large septates, whereas a cystadenocarcinoma often contains septates, abnormal blood flow, increased vascularity, or all of these. However, it is impossible to definitively distinguish a cystadenoma from a cystadenocarcinoma using US imaging alone.

Functional cysts usually resolve by the second trimester. A cyst warrants closer scrutiny when it persists, is larger than 5 cm in diameter, or has a complex appearance on US.

CA-125 may be useful after the first trimester

The serum CA-125 level is typically elevated during the first trimester, but may be useful during later assessment or for follow-up of a malignancy.1

A markedly elevated serum level of alpha-fetoprotein (fractionated in some cases) has been reported in some gravidas with an endodermal sinus or mixed germ-cell ovarian tumor.2 Alpha-fetoprotein should be measured when there is suspicion for a germ-cell tumor based on clinical or US findings.

When a mass is discovered during cesarean section

Occasionally, an adnexal mass is detected at the time of cesarean section (FIGURE 1).3 This phenomenon is increasingly common, given the large number of cesarean deliveries in the United States. To eliminate the need for future surgery and avoid a delay in the diagnosis of an ovarian malignancy, inspect the adnexa routinely after closing the uterine incision in all women who deliver by cesarean section.

FIGURE 1 Mass discovered at cesarean section

This cystic tumor was discovered at cesarean section that was undertaken for obstetric indications.

CASE 2 LMP tumor is suspected

A 36-year-old gravida 3 para 1011 makes a prenatal visit during the first trimester. Her previous delivery was a cesarean section through a Pfannenstiel incision for a breech presentation. US imaging reveals a 6-week, 5-day fetus and a complex left adnexal mass, 4.5×3.9×4.1 cm. Imaging is repeated 1 month later at a tertiary-care center and shows an 11-week viable fetus, a right ovary with a corpus luteum cyst, and a left ovary with a 6.6×4 cm cystic mass with extensive vascular surface papillations that is suspicious for a low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumor. In several sonograms prior to the pregnancy, this mass appeared to be solid and was 3 cm in size.

When is surgery warranted?

Surgery is indicated when physical examination or imaging of a pregnant woman reveals an adnexal mass that is suspicious for malignancy, but the physician must weigh the benefit of prompt surgery against the risk to the pregnancy. This equation can be complicated in several ways. For example, surgical staging of clinically early ovarian cancer is more difficult due to the pregnant uterus, which is more extensively manipulated during these procedures. In addition, an optimal operation sometimes necessitates removal of the uterus.

At 13 weeks’ gestation, the patient described in case 2 underwent laparoscopy with peritoneal washings and left salpingo-oophorectomy, but the tumor ruptured during removal. Final pathology showed it to be a serous LMP tumor involving the surface of the left ovary. Washings were in line with this diagnosis.

The pregnancy continued uneventfully, and a repeat cesarean section was performed at 37 weeks through the Pfannenstiel scar, followed by limited surgical staging. Exploration and all biopsies were negative, and the final diagnosis was a stage 1C serous LMP tumor of the ovary.

The patient articulated a desire to preserve her fertility and was monitored with US imaging of the remaining ovary every 6 months.

Does ‘indolent’ behavior of malignancy justify watchful waiting?

LMP tumors comprise a relatively large percentage of ovarian “cancers” encountered during pregnancy. Some authors report the accurate identification of these tumors prospectively, based on ultrasonographic characteristics.4,5 When an LMP tumor is the likely diagnosis, serial observation during pregnancy may be appropriate because of the indolent nature of the tumor. Further studies are needed to refine preoperative diagnosis and determine the overall safety of this approach.

When the problem is acute

In rare cases, a pregnant patient will have (or develop during observation) an acute problem due to torsion or rupture of an adnexal mass. Some ovarian cancers may present acutely, such as a rapidly growing malignant germ-cell tumor or a ruptured and hemorrhaging granulosecell tumor. Emergent surgery is necessary to manage the acute adnexal disease and reduce the likelihood of pregnancy loss. These events are infrequent, occurring in less than 10% of women with a known, persistent adnexal mass during pregnancy.4-14 Furthermore, recent studies have not found a substantial pregnancy complication rate associated with such emergency surgeries.

CASE 3 Suspicious mass, ascites signal need for surgery

A 19-year-old gravida 1 para 0 seeks prenatal care at 17 weeks’ gestation, complaining of rapidly enlarging abdominal girth. The physical examination estimates gestational size to be considerably greater than dates, but US is consistent with a 17-week intrauterine pregnancy. Imaging also reveals a 12-cm heterogenous left adnexal mass and a large amount of ascites.

Surgery is clearly warranted, but how extensive should it be?

When a malignancy is detected, a thorough staging procedure may be justified, depending on gestational age, exposure, desires of the patient, and operative findings. A midline incision is preferred.

Pregnant and nonpregnant women with stage 1A or 1C epithelial ovarian cancer who undergo fertility-preserving surgery (with chemotherapy in selected patients) have a good prognosis and a high likelihood of achieving a subsequent normal pregnancy.15 The same is true for women with a malignant germ-cell tumor of the ovary, even when disease is advanced.16 However, careful surgical staging is necessary.

The most important consideration when deciding whether to continue the pregnancy is the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. Depending on the gestational age and diagnosis, a short delay (4 to 6 weeks) may be appropriate to allow the pregnancy to progress beyond the first trimester or to maturity.

In case 3, a laparotomy was performed at 19 weeks’ gestation via a midline incision, and approximately 5.3 L of ascites was evacuated. A large, nonadherent left ovarian tumor was removed. The right ovary appeared to be normal, as did the gravid uterus, which was minimally manipulated. The rest of the surgical exploration was normal, and the distal portion of the omentum was excised. The frozen-section diagnosis was a malignant stromal tumor. Final pathology showed an 18×13.5×8.8 cm, poorly differentiated, SertoliLeydig-cell tumor with heterologous elements in the form of mucinous epithelium. The omentum was negative for tumor.

Chemotherapy was initiated in the third trimester, based on the limited data available, with intravenous etoposide and platinum administered every 21 days. The patient received 3 cycles of chemotherapy prior to delivery.

At 37 weeks’ gestation, labor was successfully induced. After delivery, bleomycin was added to the chemotherapy regimen, and 3 additional courses with all 3 agents were administered. The patient was lost to follow-up shortly after completing chemotherapy.

Clearly, an informed discussion of the options with the patient is imperative before any surgery, especially when chemotherapy may be delayed. Pregnancy does not appear to alter the prognosis for the patient with an ovarian malignancy, and ovarian cancer has not been reported to metastasize to the fetus.

Pregnant women have a very low rate of ovarian cancer

Leiserowitz GS, Xing G, Cress R, Brahmbhatt B, Dalrymple JL, Smith LH. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: how often are they malignant? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:315–321.

Ovarian malignancies are rare during pregnancy. When they do occur, they are likely to be early stage and to have a favorable outcome, according to this recent population-based study.

Using 3 large databases containing records on 4,846,505 California obstetric patients between 1991 and 1999, Leiserowitz and colleagues identified 9,375 women who had an ovarian mass associated with pregnancy. Of these, 87 had ovarian cancer and 115 had a low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumor, for a cancer occurrence rate of 0.93%, or 0.0179 per 1,000 deliveries. Thirty-four of the 87 cancers were germ-cell tumors.

Of the 87 ovarian cancers, 65.5% were localized, 6.9% regional, 23% remote, and 4.6% of unknown stage. The respective rates for LMP tumors were 81.7%, 7.8%, 4.4%, and 6.1%.

Women with malignant tumors were more likely than pregnant controls without cancer to undergo cesarean delivery, hysterectomy, transfusion, and prolonged hospitalization. These women did not, however, have a higher rate of adverse neonatal outcomes.

When cancer is advanced

Few data shed light on whether a pregnancy should continue when ovarian cancer is advanced.17 The definitive surgical approach must be highly individualized.

It is not always possible to make an accurate diagnosis based on a frozen section. In such a case, the pregnancy should be preserved until the time of definitive diagnosis. As always, the patient’s wishes and gestational age must be considered.

How factors besides malignancy can influence care