Article

Recalcitrant Folliculitis Decalvans Treatment Outcomes With Biologics and Small Molecule Inhibitors

- Author:

- Tamara Fakhoury, DO

- Katelyn Urban, DO

- Leila Ettefagh, MD

- Navid Nami, DO

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, Janus kinase inhibitors, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies have shown success in the...

Article

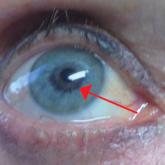

Bimatoprost-Induced Iris Hyperpigmentation: Beauty in the Darkened Eye of the Beholder

- Author:

- Michael B. Lipp, DO

- Leela Athalye, DO

- Navid Nami, DO

Iris hyperpigmentation can occur when bimatoprost eye drops are applied to the eyes for treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma, but reports...

Article

Ice Pack–Induced Perniosis: A Rare and Underrecognized Association

- Author:

- Donna Tran, DO

- Jessica Riley, DO

- Anny Xiao, DO

- Shirlene Jay, MD

- Paul Shitabata, MD

- Navid Nami, DO

Perniosis, or chilblain, is characterized by skin lesions that occur as an abnormal reaction to exposure to cold and damp conditions. Ice pack–...

Article

A Rare Case of Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type

- Author:

- Leela Athalye, DO

- Navid Nami, DO

- Paul Shitabata, MD

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (DLBCLLT) is a rare, intermediately aggressive form of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma...

Article

Collagenous and Elastotic Marginal Plaques of the Hands

- Author:

- Mayha Patel, DO

- Leela Athalye, DO

- Paul Shitabata, MD

- Mark F. Maida, MD

- Navid Nami, DO