User login

Telemedicine: Navigating legal issues

In the first 2 articles of this series, “Telemedicine: A primer for today’s ObGyn” and “Telemedicine: Common hurdles and proper coding for ObGyns,” which appeared in the May and June issues of

Legal issues surrounding telemedicine

There are numerous legal, regulatory, and compliance issues that existed before the pandemic that likely will continue to be of concern postpandemic. Although the recent 1135 waiver (allowing Medicare to pay for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telehealth)1 and other regulations are now in place for almost every aspect of telemedicine, virtual medicine is not a free-for-all (even though it may seem like it). Practicing ethical telemedicine entails abiding by numerous federal and state-specific laws and requirements. It is important to be aware of the laws in each state in which your patients are located and to practice according to the requirements of these laws. This often requires consultation with an experienced health care attorney who is knowledgeable about the use of telemedicine and who can help you with issues surrounding:

- Malpractice insurance. It is an important first step to contact your practice’s malpractice insurance carrier and confirm coverage for telemedicine visits. Telemedicine visits are considered the same as in-person visits when determining scope of practice and malpractice liability. Nevertheless, a best practice is to have written verification from your malpractice carrier about the types of telemedicine services and claims for which your ObGyn practice is covered. Additionally, if you care for patients virtually who live in a state in which you are not licensed, check with your carrier to determine if potential claims will be covered.

- Corporate practice laws. These laws require that your practice be governed by a health care professional and not someone with a nonmedical background. This becomes important if you are looking to create a virtual practice in another state. States that prohibit the corporate practice of medicine have state-specific mandates that require strict adherence. Consult with a health care attorney before entering into a business arrangement with a nonphysician or corporate entity.

- Delegation agreement requirements. These laws require physician collaboration and/or supervision of allied health care workers such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) and may limit the number of allied health care providers that a physician may supervise. Many states are allowing allied health care workers to practice at the top of their license, but this is still state specific. Thus, it is an important issue to consider, especially for practices that rely heavily on the services of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), for example, who have a broad scope of practice and who may be qualified to care for many common ObGyn problems.

- Informed consent requirements. Some states have no requirements regarding consent for a virtual visit. Others require either written or verbal consent. In states that do not require informed consent, it is best practice to nevertheless obtain either written or oral consent and to document in the patient’s record that consent was obtained before initiating a virtual visit. The consent should follow state-mandated disclosures, as well as the practice’s policies regarding billing, scheduling, and cancellations of telemedicine visits.

- Interstate licensing laws. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and state licensure waivers are in place to allow physicians to care for patients outside the physician’s home state, but these waivers likely will be lifted postpandemic. Once waivers are lifted, physicians will need to be licensed not only in the state in which they practice but also in the state where the patient is located at the time of treatment. Even physicians who practice in states that belong to the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact2 must apply for and obtain a license to practice within Compact member states. Membership in the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact expedites the licensure process, but does not alleviate the need to obtain a license to practice in each member state. To ensure compliance with interstate licensure laws, seek advice from a health care attorney specializing in telemedicine.

- Drug monitoring laws. The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 20083 implemented a requirement that physicians have at least one in-person, face-to-face visit with patients before prescribing a controlled substance for the first time. Because state laws may vary, we suggest consulting with a health care attorney to understand your state’s requirements for prescribing controlled substances to new patients and when using telemedicine (see “Prescription drugs” at https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/prescription.html for more information).

- Data privacy and security. From a content perspective, health care data and personally identifiable information are extremely rich, which makes electronic health records (EHRs), or the digital form of patients’ medical histories and other data, particularly tempting targets for hackers and cyber criminals. We caution that services such as Facetime and Skype are not encrypted; they have been granted waivers for telemedicine use, but these waivers are probably not going to be permanent once the COVID-19 crisis passes.

- HIPAA compliance. Generally—and certainly under normal circumstances—telemedicine is subject to the same rules governing protected health information (PHI) as any other technology and process used in physician practices. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule includes guidelines on telemedicine and stipulates that only authorized users should have access to ePHI, that a system of secure communication must be established to protect the security of ePHI, and that a system to monitor communications must be maintained, among other requirements.4 Third parties that provide telemedicine, data storage, and other services, with a few exceptions, must have a business associate agreement (BAA) with a covered entity. Covered entities include health care providers, health plans, and health and health care clearinghouses. Such an agreement should include specific language that ensures that HIPAA requirements will be met and that governs permitted and required uses of PHI, strictly limits other uses of PHI, and establishes appropriate safeguards and steps that must be taken in the event of a breach or disallowed disclosure of PHI. Best practice requires that providers establish robust protocols, policies, and processes for handling sensitive information.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, certain HIPAA restrictions relating to telemedicine have been temporarily waived by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). More specifically, HHS Secretary Alex Azar has exercised his authority to waive sanctions against covered hospitals for noncompliance with requirements: to obtain a patient’s consent to speak with family members or friends involved in the patient’s care, to distribute a notice of privacy practices, to request privacy restrictions, to request confidential communications, and the use of nonpublic facing audio and video communications products, among others.5 These are temporary measures only; once the national public health emergency has passed or at the HHS Secretary’s discretion based on new developments, this position on discretionary nonenforcement may end.

Continue to: Crisis creates opportunity: The future of telemedicine...

Crisis creates opportunity: The future of telemedicine

It was just a few years ago when the use of telemedicine was relegated to treating patients in only rural areas or those located a great distance from brick and mortar practices. But the pandemic, along with the coincident relaxation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) requirements for conducting telemedicine visits has made the technology highly attractive to ObGyns who can now treat many patients 24/7 from their homes using laptops and even mobile devices. In addition, the pandemic has prompted an expansion of current procedural terminology (CPT) codes that makes it possible to bill patients for telemedicine services and be appropriately compensated.

Thus, as awful as COVID-19 is, we can conclude that it has provided us with opportunities. We predict that when the crisis has abated, although the current relaxation of HIPAA guidelines will probably be rescinded, restrictions will not likely return to precoronavirus status; changes will certainly be made, and telemedicine will likely become part and parcel of caring for ObGyn patients.

Telemedicine has been used successfully for years to improve patient access to medical care while reducing health care costs. In 2016, an estimated 61% of US health care institutions and 40% to 50% of US hospitals used telemedicine.6 And according to the results of a survey of America’s physicians conducted in April 2020, almost half (48%) are treating patients through telemedicine, which is up from just 18% 2 years ago.7

Letting loose the genie in the bottle

Widespread use of telemedicine traditionally has been limited by low reimbursement rates and interstate licensing and practice issues, but we predict that the use of telemedicine is going to significantly increase in the future. Here’s why:8 Disruptive innovation was defined by Professor Clayton Christensen of the Harvard Business School in 1997.9 Disruptive innovation explains the process by which a disruptive force spurs the development of simple, convenient, and affordable solutions that then replace processes that are expensive and complicated. According to Christensen, a critical element of the process is a technology that makes a product or service more accessible to a larger number of people while reducing cost and increasing ease of use. For example, innovations making equipment for dialysis cheaper and simpler helped make it possible to administer the treatment in neighborhood clinics, rather than in centralized hospitals, thus disrupting the hospital’s share of the dialysis business.

The concept of telemedicine and the technology for its implementation have been available for more than 15 years. However, it was the coronavirus that released the genie from the bottle, serving as the disruptive force to release the innovation. Telemedicine has demonstrated that the technology offers solutions that address patients’ urgent, unmet needs for access to care at an affordable price and that enhances the productivity of the ObGyn. The result is simple, convenient, and affordable; patients can readily access the medical care they need to effectively maintain their health or manage conditions that arise.

Telemedicine has reached a level of critical mass. Data suggest that patients, especially younger ones, have accepted and appreciate the use of this technology.10 It gives patients more opportunities to receive health care in their homes or at work where they feel more comfortable and less anxious than they do in physicians’ offices.

Several other health care issues may be altered by telemedicine.

The physician shortage. If the data are to be believed, there will be a significant shortage of physicians—and perhaps ObGyns—in the near future.11 Telemedicine can help the problem by making it possible to provide medical care not only in rural areas where there are no ObGyns but also in urban areas where a shortage may be looming.

Continuing medical education (CME). CME is moving from large, expensive, in-person conferences to virtual conferences and online learning.

The American health care budget is bloated with expenses exceeding $3 trillion.12 Telemedicine can help reduce health care costs by facilitating patient appointments that do not require office staff or many of the overhead expenses associated with brick and mortar operations. Telemedicine reduces the financial impact of patient no-shows. Because patients are keen on participating, the use of telemedicine likely will improve patient engagement and clinical outcomes. Telemedicine already has a reputation of reducing unnecessary office and emergency room visits and hospital admissions.13

Clinical trials. One of the obstacles to overcome in the early stages of a clinical trial is finding participants. Telemedicine will make patient recruitment more straightforward. And because telemedicine makes distance from the office a nonissue, recruiters will be less restricted by geographic boundaries.

In addition, telemedicine allows for the participants of the trial to stay in their homes most of the time while wearing remote monitoring devices. Such devices would enable trial researchers to spot deviations from patients’ baseline readings.

The bottom line

COVID-19 has provided the opportunity for us to see how telemedicine can contribute to reducing the spread of infectious diseases by protecting physicians, their staff, and patients themselves. Once the COVID-19 crisis has passed, it is likely that telemedicine will continue to move health care delivery from the hospital or clinic into the home. The growth and integration of information and communication technologies into health care delivery holds great potential for patients, providers, and payers in health systems of the future. ●

CVS is using telemedicine to complement the company’s retail “Minute Clinic,” which offers routine preventive and clinical services, such as vaccine administration, disease screenings, treatment for minor illnesses and injuries, and monitoring of chronic conditions—services that traditionally were provided in physician’s offices only. These clinics are open 7 days per week, providing services on a walk-in basis at an affordable price—about $60 per visit compared with an average of $150 for an uninsured patient to see a primary care physician in his/her office.1 While this seems to be fulfilling an unmet need for patients, the service may prove disruptive to traditional health care delivery by removing a lucrative source of income from physicians.

Reference

1. CVS Health. CVS Health’s MinuteClinic introduces new virtual care offering. August 8, 2018. https://cvshealth.com/newsroom/press-releases/cvs-healths-minuteclinic-introduces-new-virtual-care-offering. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- CMS.gov. 1135 Waiver – At A Glance.https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertEmergPrep/Downloads/1135-Waivers-At-A-Glance.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. https://www.imlcc.org/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- American Psychiatric Association. The Ryan Haight OnlinePharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/ryan-haight-act. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- American Medical Association. HIPAA security rule and riskanalysis. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/hipaa/hipaa-security-rule-risk-analysis#:~:text=The%20HIPAA%20Security%20Rule%20requires,and%20security%20of%20this%20information. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- HHS.gov. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Content last reviewed on March 30, 2020.https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Mahar J, Rosencrance J, Rasmussen P. The Future of Telemedicine (And What’s in the Way). Consult QD. March 1,2019. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/the-future-of-telemedicine-and-whats-in-the-way. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- Merritt Hawkins. Survey: Physician Practice Patterns Changing As A Result Of COVID-19. April 22, 2020.https://www.merritthawkins.com/news-and-insights/media-room/press/-Physician-Practice-Patterns-Changing-as-a-Result-of-COVID-19/. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- The Medical Futurist. COVID-19 and the rise of telemedicine.March 31, 2020. https://medicalfuturist.com/covid-19-was-needed-for-telemedicine-to-finally-go-mainstream/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Christensen C, Euchner J. Managing disruption: an interview with Clayton Christensen. Research-Technology Management. 2011;54:1, 11-17.

- Wordstream. 4 major trends for post-COVID-19 world. Last updated May 1, 2020. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2020/03/23/covid-19-business-trends. Accessed June16, 2020.

- Rosenberg J. Physician shortage likely to impact ob/gyn workforce in coming years. AJMC. September 21, 2019. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/physician-shortage-likely-to-impact-obgyn-workforce-in-coming-years. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- CMS.gov. National Health Expenditure Data: Historical. Page last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- Cohen JK. Study: Telehealth program reduces unnecessary ED visits by 6.7%. Hospital Review. February 27, 2017.https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/telehealth/study-telehealth-program-reduces-unnecessary-ed-visits-by-6-7.html. Accessed June 23, 2020.

In the first 2 articles of this series, “Telemedicine: A primer for today’s ObGyn” and “Telemedicine: Common hurdles and proper coding for ObGyns,” which appeared in the May and June issues of

Legal issues surrounding telemedicine

There are numerous legal, regulatory, and compliance issues that existed before the pandemic that likely will continue to be of concern postpandemic. Although the recent 1135 waiver (allowing Medicare to pay for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telehealth)1 and other regulations are now in place for almost every aspect of telemedicine, virtual medicine is not a free-for-all (even though it may seem like it). Practicing ethical telemedicine entails abiding by numerous federal and state-specific laws and requirements. It is important to be aware of the laws in each state in which your patients are located and to practice according to the requirements of these laws. This often requires consultation with an experienced health care attorney who is knowledgeable about the use of telemedicine and who can help you with issues surrounding:

- Malpractice insurance. It is an important first step to contact your practice’s malpractice insurance carrier and confirm coverage for telemedicine visits. Telemedicine visits are considered the same as in-person visits when determining scope of practice and malpractice liability. Nevertheless, a best practice is to have written verification from your malpractice carrier about the types of telemedicine services and claims for which your ObGyn practice is covered. Additionally, if you care for patients virtually who live in a state in which you are not licensed, check with your carrier to determine if potential claims will be covered.

- Corporate practice laws. These laws require that your practice be governed by a health care professional and not someone with a nonmedical background. This becomes important if you are looking to create a virtual practice in another state. States that prohibit the corporate practice of medicine have state-specific mandates that require strict adherence. Consult with a health care attorney before entering into a business arrangement with a nonphysician or corporate entity.

- Delegation agreement requirements. These laws require physician collaboration and/or supervision of allied health care workers such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) and may limit the number of allied health care providers that a physician may supervise. Many states are allowing allied health care workers to practice at the top of their license, but this is still state specific. Thus, it is an important issue to consider, especially for practices that rely heavily on the services of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), for example, who have a broad scope of practice and who may be qualified to care for many common ObGyn problems.

- Informed consent requirements. Some states have no requirements regarding consent for a virtual visit. Others require either written or verbal consent. In states that do not require informed consent, it is best practice to nevertheless obtain either written or oral consent and to document in the patient’s record that consent was obtained before initiating a virtual visit. The consent should follow state-mandated disclosures, as well as the practice’s policies regarding billing, scheduling, and cancellations of telemedicine visits.

- Interstate licensing laws. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and state licensure waivers are in place to allow physicians to care for patients outside the physician’s home state, but these waivers likely will be lifted postpandemic. Once waivers are lifted, physicians will need to be licensed not only in the state in which they practice but also in the state where the patient is located at the time of treatment. Even physicians who practice in states that belong to the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact2 must apply for and obtain a license to practice within Compact member states. Membership in the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact expedites the licensure process, but does not alleviate the need to obtain a license to practice in each member state. To ensure compliance with interstate licensure laws, seek advice from a health care attorney specializing in telemedicine.

- Drug monitoring laws. The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 20083 implemented a requirement that physicians have at least one in-person, face-to-face visit with patients before prescribing a controlled substance for the first time. Because state laws may vary, we suggest consulting with a health care attorney to understand your state’s requirements for prescribing controlled substances to new patients and when using telemedicine (see “Prescription drugs” at https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/prescription.html for more information).

- Data privacy and security. From a content perspective, health care data and personally identifiable information are extremely rich, which makes electronic health records (EHRs), or the digital form of patients’ medical histories and other data, particularly tempting targets for hackers and cyber criminals. We caution that services such as Facetime and Skype are not encrypted; they have been granted waivers for telemedicine use, but these waivers are probably not going to be permanent once the COVID-19 crisis passes.

- HIPAA compliance. Generally—and certainly under normal circumstances—telemedicine is subject to the same rules governing protected health information (PHI) as any other technology and process used in physician practices. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule includes guidelines on telemedicine and stipulates that only authorized users should have access to ePHI, that a system of secure communication must be established to protect the security of ePHI, and that a system to monitor communications must be maintained, among other requirements.4 Third parties that provide telemedicine, data storage, and other services, with a few exceptions, must have a business associate agreement (BAA) with a covered entity. Covered entities include health care providers, health plans, and health and health care clearinghouses. Such an agreement should include specific language that ensures that HIPAA requirements will be met and that governs permitted and required uses of PHI, strictly limits other uses of PHI, and establishes appropriate safeguards and steps that must be taken in the event of a breach or disallowed disclosure of PHI. Best practice requires that providers establish robust protocols, policies, and processes for handling sensitive information.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, certain HIPAA restrictions relating to telemedicine have been temporarily waived by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). More specifically, HHS Secretary Alex Azar has exercised his authority to waive sanctions against covered hospitals for noncompliance with requirements: to obtain a patient’s consent to speak with family members or friends involved in the patient’s care, to distribute a notice of privacy practices, to request privacy restrictions, to request confidential communications, and the use of nonpublic facing audio and video communications products, among others.5 These are temporary measures only; once the national public health emergency has passed or at the HHS Secretary’s discretion based on new developments, this position on discretionary nonenforcement may end.

Continue to: Crisis creates opportunity: The future of telemedicine...

Crisis creates opportunity: The future of telemedicine

It was just a few years ago when the use of telemedicine was relegated to treating patients in only rural areas or those located a great distance from brick and mortar practices. But the pandemic, along with the coincident relaxation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) requirements for conducting telemedicine visits has made the technology highly attractive to ObGyns who can now treat many patients 24/7 from their homes using laptops and even mobile devices. In addition, the pandemic has prompted an expansion of current procedural terminology (CPT) codes that makes it possible to bill patients for telemedicine services and be appropriately compensated.

Thus, as awful as COVID-19 is, we can conclude that it has provided us with opportunities. We predict that when the crisis has abated, although the current relaxation of HIPAA guidelines will probably be rescinded, restrictions will not likely return to precoronavirus status; changes will certainly be made, and telemedicine will likely become part and parcel of caring for ObGyn patients.

Telemedicine has been used successfully for years to improve patient access to medical care while reducing health care costs. In 2016, an estimated 61% of US health care institutions and 40% to 50% of US hospitals used telemedicine.6 And according to the results of a survey of America’s physicians conducted in April 2020, almost half (48%) are treating patients through telemedicine, which is up from just 18% 2 years ago.7

Letting loose the genie in the bottle

Widespread use of telemedicine traditionally has been limited by low reimbursement rates and interstate licensing and practice issues, but we predict that the use of telemedicine is going to significantly increase in the future. Here’s why:8 Disruptive innovation was defined by Professor Clayton Christensen of the Harvard Business School in 1997.9 Disruptive innovation explains the process by which a disruptive force spurs the development of simple, convenient, and affordable solutions that then replace processes that are expensive and complicated. According to Christensen, a critical element of the process is a technology that makes a product or service more accessible to a larger number of people while reducing cost and increasing ease of use. For example, innovations making equipment for dialysis cheaper and simpler helped make it possible to administer the treatment in neighborhood clinics, rather than in centralized hospitals, thus disrupting the hospital’s share of the dialysis business.

The concept of telemedicine and the technology for its implementation have been available for more than 15 years. However, it was the coronavirus that released the genie from the bottle, serving as the disruptive force to release the innovation. Telemedicine has demonstrated that the technology offers solutions that address patients’ urgent, unmet needs for access to care at an affordable price and that enhances the productivity of the ObGyn. The result is simple, convenient, and affordable; patients can readily access the medical care they need to effectively maintain their health or manage conditions that arise.

Telemedicine has reached a level of critical mass. Data suggest that patients, especially younger ones, have accepted and appreciate the use of this technology.10 It gives patients more opportunities to receive health care in their homes or at work where they feel more comfortable and less anxious than they do in physicians’ offices.

Several other health care issues may be altered by telemedicine.

The physician shortage. If the data are to be believed, there will be a significant shortage of physicians—and perhaps ObGyns—in the near future.11 Telemedicine can help the problem by making it possible to provide medical care not only in rural areas where there are no ObGyns but also in urban areas where a shortage may be looming.

Continuing medical education (CME). CME is moving from large, expensive, in-person conferences to virtual conferences and online learning.

The American health care budget is bloated with expenses exceeding $3 trillion.12 Telemedicine can help reduce health care costs by facilitating patient appointments that do not require office staff or many of the overhead expenses associated with brick and mortar operations. Telemedicine reduces the financial impact of patient no-shows. Because patients are keen on participating, the use of telemedicine likely will improve patient engagement and clinical outcomes. Telemedicine already has a reputation of reducing unnecessary office and emergency room visits and hospital admissions.13

Clinical trials. One of the obstacles to overcome in the early stages of a clinical trial is finding participants. Telemedicine will make patient recruitment more straightforward. And because telemedicine makes distance from the office a nonissue, recruiters will be less restricted by geographic boundaries.

In addition, telemedicine allows for the participants of the trial to stay in their homes most of the time while wearing remote monitoring devices. Such devices would enable trial researchers to spot deviations from patients’ baseline readings.

The bottom line

COVID-19 has provided the opportunity for us to see how telemedicine can contribute to reducing the spread of infectious diseases by protecting physicians, their staff, and patients themselves. Once the COVID-19 crisis has passed, it is likely that telemedicine will continue to move health care delivery from the hospital or clinic into the home. The growth and integration of information and communication technologies into health care delivery holds great potential for patients, providers, and payers in health systems of the future. ●

CVS is using telemedicine to complement the company’s retail “Minute Clinic,” which offers routine preventive and clinical services, such as vaccine administration, disease screenings, treatment for minor illnesses and injuries, and monitoring of chronic conditions—services that traditionally were provided in physician’s offices only. These clinics are open 7 days per week, providing services on a walk-in basis at an affordable price—about $60 per visit compared with an average of $150 for an uninsured patient to see a primary care physician in his/her office.1 While this seems to be fulfilling an unmet need for patients, the service may prove disruptive to traditional health care delivery by removing a lucrative source of income from physicians.

Reference

1. CVS Health. CVS Health’s MinuteClinic introduces new virtual care offering. August 8, 2018. https://cvshealth.com/newsroom/press-releases/cvs-healths-minuteclinic-introduces-new-virtual-care-offering. Accessed June 16, 2020.

In the first 2 articles of this series, “Telemedicine: A primer for today’s ObGyn” and “Telemedicine: Common hurdles and proper coding for ObGyns,” which appeared in the May and June issues of

Legal issues surrounding telemedicine

There are numerous legal, regulatory, and compliance issues that existed before the pandemic that likely will continue to be of concern postpandemic. Although the recent 1135 waiver (allowing Medicare to pay for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telehealth)1 and other regulations are now in place for almost every aspect of telemedicine, virtual medicine is not a free-for-all (even though it may seem like it). Practicing ethical telemedicine entails abiding by numerous federal and state-specific laws and requirements. It is important to be aware of the laws in each state in which your patients are located and to practice according to the requirements of these laws. This often requires consultation with an experienced health care attorney who is knowledgeable about the use of telemedicine and who can help you with issues surrounding:

- Malpractice insurance. It is an important first step to contact your practice’s malpractice insurance carrier and confirm coverage for telemedicine visits. Telemedicine visits are considered the same as in-person visits when determining scope of practice and malpractice liability. Nevertheless, a best practice is to have written verification from your malpractice carrier about the types of telemedicine services and claims for which your ObGyn practice is covered. Additionally, if you care for patients virtually who live in a state in which you are not licensed, check with your carrier to determine if potential claims will be covered.

- Corporate practice laws. These laws require that your practice be governed by a health care professional and not someone with a nonmedical background. This becomes important if you are looking to create a virtual practice in another state. States that prohibit the corporate practice of medicine have state-specific mandates that require strict adherence. Consult with a health care attorney before entering into a business arrangement with a nonphysician or corporate entity.

- Delegation agreement requirements. These laws require physician collaboration and/or supervision of allied health care workers such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) and may limit the number of allied health care providers that a physician may supervise. Many states are allowing allied health care workers to practice at the top of their license, but this is still state specific. Thus, it is an important issue to consider, especially for practices that rely heavily on the services of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), for example, who have a broad scope of practice and who may be qualified to care for many common ObGyn problems.

- Informed consent requirements. Some states have no requirements regarding consent for a virtual visit. Others require either written or verbal consent. In states that do not require informed consent, it is best practice to nevertheless obtain either written or oral consent and to document in the patient’s record that consent was obtained before initiating a virtual visit. The consent should follow state-mandated disclosures, as well as the practice’s policies regarding billing, scheduling, and cancellations of telemedicine visits.

- Interstate licensing laws. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, federal and state licensure waivers are in place to allow physicians to care for patients outside the physician’s home state, but these waivers likely will be lifted postpandemic. Once waivers are lifted, physicians will need to be licensed not only in the state in which they practice but also in the state where the patient is located at the time of treatment. Even physicians who practice in states that belong to the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact2 must apply for and obtain a license to practice within Compact member states. Membership in the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact expedites the licensure process, but does not alleviate the need to obtain a license to practice in each member state. To ensure compliance with interstate licensure laws, seek advice from a health care attorney specializing in telemedicine.

- Drug monitoring laws. The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 20083 implemented a requirement that physicians have at least one in-person, face-to-face visit with patients before prescribing a controlled substance for the first time. Because state laws may vary, we suggest consulting with a health care attorney to understand your state’s requirements for prescribing controlled substances to new patients and when using telemedicine (see “Prescription drugs” at https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/prescription.html for more information).

- Data privacy and security. From a content perspective, health care data and personally identifiable information are extremely rich, which makes electronic health records (EHRs), or the digital form of patients’ medical histories and other data, particularly tempting targets for hackers and cyber criminals. We caution that services such as Facetime and Skype are not encrypted; they have been granted waivers for telemedicine use, but these waivers are probably not going to be permanent once the COVID-19 crisis passes.

- HIPAA compliance. Generally—and certainly under normal circumstances—telemedicine is subject to the same rules governing protected health information (PHI) as any other technology and process used in physician practices. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule includes guidelines on telemedicine and stipulates that only authorized users should have access to ePHI, that a system of secure communication must be established to protect the security of ePHI, and that a system to monitor communications must be maintained, among other requirements.4 Third parties that provide telemedicine, data storage, and other services, with a few exceptions, must have a business associate agreement (BAA) with a covered entity. Covered entities include health care providers, health plans, and health and health care clearinghouses. Such an agreement should include specific language that ensures that HIPAA requirements will be met and that governs permitted and required uses of PHI, strictly limits other uses of PHI, and establishes appropriate safeguards and steps that must be taken in the event of a breach or disallowed disclosure of PHI. Best practice requires that providers establish robust protocols, policies, and processes for handling sensitive information.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, certain HIPAA restrictions relating to telemedicine have been temporarily waived by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). More specifically, HHS Secretary Alex Azar has exercised his authority to waive sanctions against covered hospitals for noncompliance with requirements: to obtain a patient’s consent to speak with family members or friends involved in the patient’s care, to distribute a notice of privacy practices, to request privacy restrictions, to request confidential communications, and the use of nonpublic facing audio and video communications products, among others.5 These are temporary measures only; once the national public health emergency has passed or at the HHS Secretary’s discretion based on new developments, this position on discretionary nonenforcement may end.

Continue to: Crisis creates opportunity: The future of telemedicine...

Crisis creates opportunity: The future of telemedicine

It was just a few years ago when the use of telemedicine was relegated to treating patients in only rural areas or those located a great distance from brick and mortar practices. But the pandemic, along with the coincident relaxation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) requirements for conducting telemedicine visits has made the technology highly attractive to ObGyns who can now treat many patients 24/7 from their homes using laptops and even mobile devices. In addition, the pandemic has prompted an expansion of current procedural terminology (CPT) codes that makes it possible to bill patients for telemedicine services and be appropriately compensated.

Thus, as awful as COVID-19 is, we can conclude that it has provided us with opportunities. We predict that when the crisis has abated, although the current relaxation of HIPAA guidelines will probably be rescinded, restrictions will not likely return to precoronavirus status; changes will certainly be made, and telemedicine will likely become part and parcel of caring for ObGyn patients.

Telemedicine has been used successfully for years to improve patient access to medical care while reducing health care costs. In 2016, an estimated 61% of US health care institutions and 40% to 50% of US hospitals used telemedicine.6 And according to the results of a survey of America’s physicians conducted in April 2020, almost half (48%) are treating patients through telemedicine, which is up from just 18% 2 years ago.7

Letting loose the genie in the bottle

Widespread use of telemedicine traditionally has been limited by low reimbursement rates and interstate licensing and practice issues, but we predict that the use of telemedicine is going to significantly increase in the future. Here’s why:8 Disruptive innovation was defined by Professor Clayton Christensen of the Harvard Business School in 1997.9 Disruptive innovation explains the process by which a disruptive force spurs the development of simple, convenient, and affordable solutions that then replace processes that are expensive and complicated. According to Christensen, a critical element of the process is a technology that makes a product or service more accessible to a larger number of people while reducing cost and increasing ease of use. For example, innovations making equipment for dialysis cheaper and simpler helped make it possible to administer the treatment in neighborhood clinics, rather than in centralized hospitals, thus disrupting the hospital’s share of the dialysis business.

The concept of telemedicine and the technology for its implementation have been available for more than 15 years. However, it was the coronavirus that released the genie from the bottle, serving as the disruptive force to release the innovation. Telemedicine has demonstrated that the technology offers solutions that address patients’ urgent, unmet needs for access to care at an affordable price and that enhances the productivity of the ObGyn. The result is simple, convenient, and affordable; patients can readily access the medical care they need to effectively maintain their health or manage conditions that arise.

Telemedicine has reached a level of critical mass. Data suggest that patients, especially younger ones, have accepted and appreciate the use of this technology.10 It gives patients more opportunities to receive health care in their homes or at work where they feel more comfortable and less anxious than they do in physicians’ offices.

Several other health care issues may be altered by telemedicine.

The physician shortage. If the data are to be believed, there will be a significant shortage of physicians—and perhaps ObGyns—in the near future.11 Telemedicine can help the problem by making it possible to provide medical care not only in rural areas where there are no ObGyns but also in urban areas where a shortage may be looming.

Continuing medical education (CME). CME is moving from large, expensive, in-person conferences to virtual conferences and online learning.

The American health care budget is bloated with expenses exceeding $3 trillion.12 Telemedicine can help reduce health care costs by facilitating patient appointments that do not require office staff or many of the overhead expenses associated with brick and mortar operations. Telemedicine reduces the financial impact of patient no-shows. Because patients are keen on participating, the use of telemedicine likely will improve patient engagement and clinical outcomes. Telemedicine already has a reputation of reducing unnecessary office and emergency room visits and hospital admissions.13

Clinical trials. One of the obstacles to overcome in the early stages of a clinical trial is finding participants. Telemedicine will make patient recruitment more straightforward. And because telemedicine makes distance from the office a nonissue, recruiters will be less restricted by geographic boundaries.

In addition, telemedicine allows for the participants of the trial to stay in their homes most of the time while wearing remote monitoring devices. Such devices would enable trial researchers to spot deviations from patients’ baseline readings.

The bottom line

COVID-19 has provided the opportunity for us to see how telemedicine can contribute to reducing the spread of infectious diseases by protecting physicians, their staff, and patients themselves. Once the COVID-19 crisis has passed, it is likely that telemedicine will continue to move health care delivery from the hospital or clinic into the home. The growth and integration of information and communication technologies into health care delivery holds great potential for patients, providers, and payers in health systems of the future. ●

CVS is using telemedicine to complement the company’s retail “Minute Clinic,” which offers routine preventive and clinical services, such as vaccine administration, disease screenings, treatment for minor illnesses and injuries, and monitoring of chronic conditions—services that traditionally were provided in physician’s offices only. These clinics are open 7 days per week, providing services on a walk-in basis at an affordable price—about $60 per visit compared with an average of $150 for an uninsured patient to see a primary care physician in his/her office.1 While this seems to be fulfilling an unmet need for patients, the service may prove disruptive to traditional health care delivery by removing a lucrative source of income from physicians.

Reference

1. CVS Health. CVS Health’s MinuteClinic introduces new virtual care offering. August 8, 2018. https://cvshealth.com/newsroom/press-releases/cvs-healths-minuteclinic-introduces-new-virtual-care-offering. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- CMS.gov. 1135 Waiver – At A Glance.https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertEmergPrep/Downloads/1135-Waivers-At-A-Glance.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. https://www.imlcc.org/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- American Psychiatric Association. The Ryan Haight OnlinePharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/ryan-haight-act. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- American Medical Association. HIPAA security rule and riskanalysis. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/hipaa/hipaa-security-rule-risk-analysis#:~:text=The%20HIPAA%20Security%20Rule%20requires,and%20security%20of%20this%20information. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- HHS.gov. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Content last reviewed on March 30, 2020.https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Mahar J, Rosencrance J, Rasmussen P. The Future of Telemedicine (And What’s in the Way). Consult QD. March 1,2019. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/the-future-of-telemedicine-and-whats-in-the-way. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- Merritt Hawkins. Survey: Physician Practice Patterns Changing As A Result Of COVID-19. April 22, 2020.https://www.merritthawkins.com/news-and-insights/media-room/press/-Physician-Practice-Patterns-Changing-as-a-Result-of-COVID-19/. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- The Medical Futurist. COVID-19 and the rise of telemedicine.March 31, 2020. https://medicalfuturist.com/covid-19-was-needed-for-telemedicine-to-finally-go-mainstream/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Christensen C, Euchner J. Managing disruption: an interview with Clayton Christensen. Research-Technology Management. 2011;54:1, 11-17.

- Wordstream. 4 major trends for post-COVID-19 world. Last updated May 1, 2020. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2020/03/23/covid-19-business-trends. Accessed June16, 2020.

- Rosenberg J. Physician shortage likely to impact ob/gyn workforce in coming years. AJMC. September 21, 2019. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/physician-shortage-likely-to-impact-obgyn-workforce-in-coming-years. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- CMS.gov. National Health Expenditure Data: Historical. Page last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- Cohen JK. Study: Telehealth program reduces unnecessary ED visits by 6.7%. Hospital Review. February 27, 2017.https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/telehealth/study-telehealth-program-reduces-unnecessary-ed-visits-by-6-7.html. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- CMS.gov. 1135 Waiver – At A Glance.https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertEmergPrep/Downloads/1135-Waivers-At-A-Glance.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. https://www.imlcc.org/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- American Psychiatric Association. The Ryan Haight OnlinePharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/ryan-haight-act. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- American Medical Association. HIPAA security rule and riskanalysis. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/hipaa/hipaa-security-rule-risk-analysis#:~:text=The%20HIPAA%20Security%20Rule%20requires,and%20security%20of%20this%20information. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- HHS.gov. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Content last reviewed on March 30, 2020.https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Mahar J, Rosencrance J, Rasmussen P. The Future of Telemedicine (And What’s in the Way). Consult QD. March 1,2019. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/the-future-of-telemedicine-and-whats-in-the-way. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- Merritt Hawkins. Survey: Physician Practice Patterns Changing As A Result Of COVID-19. April 22, 2020.https://www.merritthawkins.com/news-and-insights/media-room/press/-Physician-Practice-Patterns-Changing-as-a-Result-of-COVID-19/. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- The Medical Futurist. COVID-19 and the rise of telemedicine.March 31, 2020. https://medicalfuturist.com/covid-19-was-needed-for-telemedicine-to-finally-go-mainstream/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Christensen C, Euchner J. Managing disruption: an interview with Clayton Christensen. Research-Technology Management. 2011;54:1, 11-17.

- Wordstream. 4 major trends for post-COVID-19 world. Last updated May 1, 2020. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2020/03/23/covid-19-business-trends. Accessed June16, 2020.

- Rosenberg J. Physician shortage likely to impact ob/gyn workforce in coming years. AJMC. September 21, 2019. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/physician-shortage-likely-to-impact-obgyn-workforce-in-coming-years. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- CMS.gov. National Health Expenditure Data: Historical. Page last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- Cohen JK. Study: Telehealth program reduces unnecessary ED visits by 6.7%. Hospital Review. February 27, 2017.https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/telehealth/study-telehealth-program-reduces-unnecessary-ed-visits-by-6-7.html. Accessed June 23, 2020.

Telemedicine: Common hurdles and proper coding for ObGyns

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, many significant changes have occurred that have made the implementation of telemedicine easier and more attractive for gynecologic practices. In the first article in this series, we discussed the benefits of telemedicine to physicians and patients, how to get started using telemedicine, and implementing a workflow. This article will discuss the common hurdles in the process and the proper coding to use to insure reimbursement for services rendered.

Barriers to implementing telemedicine

Incorrect assumptions

Latecomers to telemedicine often assume that patients prefer face-to-face visits when, in fact, many may prefer the convenience of virtual visits. More than 50% of patients who are surveyed about their experience with telemedicine say that online tools have helped improve their relationship with their providers.1 Telemedicine has grown astronomically during the COVID-19 pandemic to the point where many patients now expect their health care providers to be able to conduct virtual visits. Practices that do not offer telemedicine may find their patients seeking services elsewhere. Nearly two-thirds of health care professionals expect their commitment to telemedicine to increase significantly in the next 3 years.2 Of those providers who have not yet adopted the practice, nearly 85% expect to implement telemedicine in the near future.3 COVID-19 has motivated the increased use of telemedicine to enhance the communication with patients, making it possible for patients to have enhanced access to health care during this pandemic while minimizing infectious transmission of COVID-19 to physicians and their staff.4

Admittedly, telemedicine is not appropriate for all patients. In general, situations that do not lend themselves to telemedicine are those for which an in-person visit is required to evaluate the patient via a physical examination, to perform a protocol-driven procedure, or provide an aggressive intervention. Additional patients for whom telemedicine may be inappropriate include those with cognitive disorders, those with language barriers, those with emergency situations that warrant an office visit or a visit to the emergency department, and patients who do not have access to the technology to conduct a virtual visit.

Cost and complexity

The process of implementing electronic health records (EHRs) left a bitter taste in the mouths of many health care professionals. But EHRs are complicated and expensive. Implementation often resulted in lost productivity. Because the learning curve was so steep, many physicians had to decrease the number of patients they saw before becoming comfortable with the conversion from paper charts to an EHR.

Telemedicine implementation is much less onerous and expensive. Telemedicine is available as a cloud-based platform, which requires less information technology (IT) support and less hardware and software. The technology required for patients to participate in telemedicine is nearly ubiquitous. According to the Pew Research Center, 96% of Americans own a cell phone (81% have a smart phone), and more than half (52%) own a tablet, so the basic equipment to connect patients to providers is already in place.5

On the provider side, the basic equipment required for a telemedicine program is a computer with video and audio capabilities and a broadband connection that is fast enough to show video in real time and to provide high-quality viewing of any images to be reviewed.

The growth in telemedicine means that telemedicine options are now more diverse, with many more affordable solutions. However, most telemedicine programs do require the purchase and set-up of new technology and equipment and the training of staff—some of which may be outside the budgets of health care providers in smaller independent practices. Many gynecologists have technology budgets that are already stretched thin. And for patients who do not have access to a smartphone or computer with Internet access, real-time telemedicine may be out of reach.

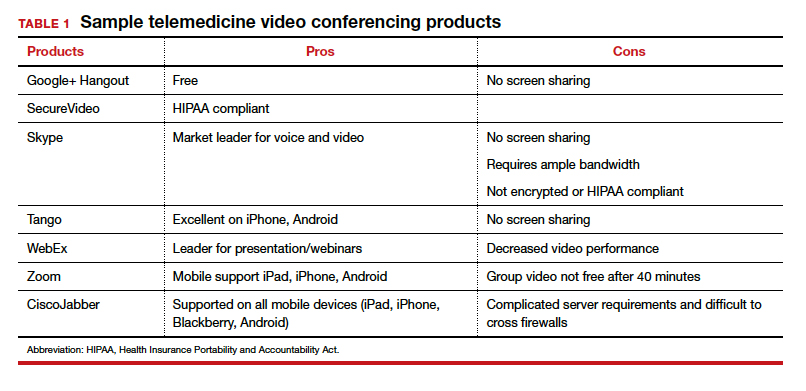

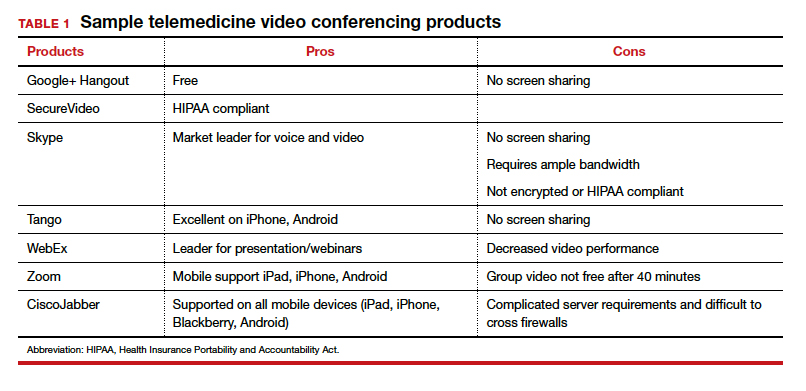

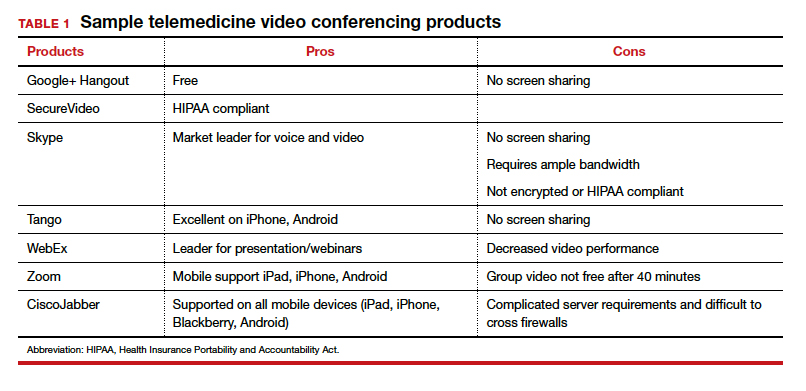

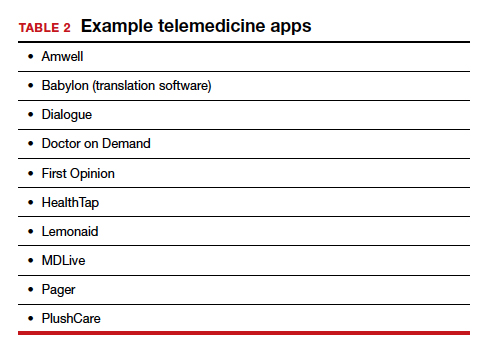

But with new guidelines put forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in March 2020, connectivity can take place inexpensively using free platforms such as Google Hangouts, Skype, Facetime, and Facebook Messenger. If a non‒HIPAA-compliant platform is used initially, conversion to a HIPAA-compliant platform is recommended.6 These platforms do not require the purchase of, or subscription to, any expensive hardware or software. The disadvantages of these programs are the lack of documentation, the failure to be Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant, and the lack of encryption; however, these disadvantages are no longer an issue after the new CMS guidelines.

Depending on the magnitude of the program, IT assistance may be needed to get started. It is imperative that the telemedicine program is interoperable with the EHR and the billing program. Otherwise, double and triple entry will erase the efficiency provided by conducting a virtual visit.

Continue to: Licensing...

Licensing

Another concern or barrier is a license to participate in telemedicine. The March 15, 2020, approval of telemedicine states that physicians who are licensed in the state where the patient is located do not require any additional license or permission to conduct virtual visits.7 CMS has temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state providers be licensed in the state where they are providing services when they are licensed in another state. For questions regarding licensure, contact your State Board of Medicine or Department of Health for information on requirements for licenses across state lines (see “Resources,” at the end of the article).

Informed consent

Just like with any other aspect of providing care for patients, obtaining informed consent is paramount. Not only is getting informed patient consent a recommended best practice of the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), but it is actually a legal requirement in many states and could be a condition of getting paid, depending on the payer. To check the requirements regarding patient consent in your state, look at The National Telehealth Policy Resource Center’s state map (see “Resources.")

Some states do not have any requirements regarding consent for a virtual visit. Others require verbal consent. Even if it is not a legal requirement in your state, consider making it a part of your practice’s policy to obtain written or verbal consent and to document in the patient’s record that consent was obtained prior to the virtual visit so that you are protected when using this new technology.

Because telemedicine is a new way of receiving care for many patients, it is important to let them know how it works including how patient confidentiality and privacy are handled, what technical equipment is required, and what they should expect in terms of scheduling, cancellations, and billing policies. A sample consent form for telemedicine use is shown in FIGURE 1.

Liability insurance

Another hurdle that must be considered is liability insurance for conducting virtual visits with patients. Gynecologists who are going to offer telemedicine care to patients should request proof in writing that their liability insurance policy covers telemedicine malpractice and that the coverage extends to other states should the patient be in another state from the state in which the gynecologist holds a license. Additionally, gynecologists who provide telemedicine care should check with liability insurers regarding any requirements or limitations to conducting a virtual visit with their patients and should document them. For example, the policy may require that the physician keep a written or recorded record of the visit in the EHR. If that is the case, then using Skype, Facebook, or Google for the virtual visit, which do not include documentation, would be less desirable.

Privacy

Certainly, there is concern about privacy, and HIPAA compliance is critical to telemedicine success. Because of the COVID-19 emergency, as of March 1, 2020, physicians may now communicate with patients, and provide telehealth services, through remote communications without penalties.8 With these changes in the HIPAA requirements, physicians may use applications that allow for video chats, including Apple FaceTime, Facebook Messenger video chat, Google Hangouts video, and Skype, to provide telehealth without risk that the Office for Civil Rights will impose a penalty for noncompliance with HIPAA rules. The consent for patients should mention that these “public” applications potentially introduce privacy risks. This is a motivation for gynecologists to consider one of the programs that promises encryption, privacy, and HIPAA compliance, such as Updox, Doxy.me, and Amazon Chime. It is also important to recognize that a virtual visit could result in colleagues (if the patient is in an office setting) or family members (if the patient is in the home environment) overhearing conversations between the health care professional and the patient. Therefore, we suggest that patients conduct virtual visits in locations in which they feel assured of some semblance of privacy.

Continue to: Compensation for telemedicine...

Compensation for telemedicine

Perhaps the biggest barrier to virtual health adoption has been compensation for telemedicine visits. Both commercial payers and CMS have been slow to enact formal policies for telemedicine reimbursement. Because of this, the common misconceptions (that providers cannot be reimbursed for telemedicine appointments or that compensation occurs at a reduced rate) have persisted, making telemedicine economically unappealing.

The good news is that this is changing; legislation in most states is quickly embracing virtual health visits as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.9 In fact, as of January 1, 2020, telemedicine services are no longer considered “optional” coverage in Medicare Advantage plans.10 Nor are they required to have an additional fee. Instead, CMS now allows telemedicine as a standard, covered benefit in all plans, enabling beneficiaries to seek care from their homes rather than requiring them to go to a health care facility.11 In the past, telemedicine was restricted for use in rural areas or when patients resided a great distance from their health care providers. Starting March 6, 2020, and for the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency, Medicare will make payment for professional services furnished to beneficiaries in all areas of the country in all settings regardless of location or distance between the patient and the health care provider.12

In addition, since March 15, 2020, CMS has expanded access to telemedicine services for all Medicare beneficiaries—not just those who have been diagnosed with COVID-19.13 The expanded access also applies to pre-COVID-19 coverage from physician offices, skilled nursing facilities, and hospitals. This means that Medicare will now make payments to physicians for telemedicine services provided in any health care facility or in a patient’s home, so that patients do not need to go to the physician’s office.

The facts are that there are parity laws and that commercial payers and CMS are required by state law to reimburse for telemedicine—often at the same rate as that for a comparable in-person visit. On the commercial side, there has been an increase in commercial parity legislation that requires health plans to cover virtual visits in the same way they cover face-to-face services. With the new guidelines for reimbursement, every state and Washington DC has parity laws in place. (To stay abreast of state-by-state changes in virtual health reimbursement, the Center for Connected Health Policy and the Advisory Board Primer are valuable resources. See “Resources.”) As long as the provider performs and documents the elements of history and decision-making, including the time spent counseling, and documents the visit as if a face-to-face visit occurred, then clinicians have a billable evaluation and management (E&M) visit.

Continue to: Virtual services for Medicare patients...

Virtual services for Medicare patients

There are 3 main types of virtual services gynecologists can provide to Medicare patients: Medicare telehealth visits, virtual check-ins, and e-visits.

Medicare telehealth visits. Largely because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicare patients may now use telecommunication technology for any services that previously occurred in an in-person communication. The gynecologist must use an interactive audio and video telecommunications system that permits real-time communication between the physician and the patient, and the patient should have a prior established relationship with the gynecologist with whom the telemedicine visit is taking place. The new guidelines indicate that the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will not conduct audits to ensure that such a prior relationship exists for claims submitted during this public health emergency.14

The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for virtual visits using synchronous audio/visual communication are:

- 99201-99295, Office visit for a new patient

- 99211-99215, Office visit for an established patient.

Important modifiers for telemedicine visits include:

- modifier 02 for POS (place of service) for telehealth Medicare

- modifier 95 for commercial payers.

(A list of all available CPT codes for telehealth services from CMS can be found in “Resources.”)

Virtual check-ins. Established Medicare patients may have a brief communication with gynecologists the traditional way using a telephone or via live video. These brief virtual services, usually 5 to 10 minutes in duration, are initiated by the patient. The purpose of the virtual check-in is to determine if an office visit or a test or procedure is indicated.

Medicare pays for these “virtual check-ins” (or brief communication technology-based services) for patients to communicate with their physicians and avoid unnecessary trips to the office. These brief virtual check-ins are only for established patients. If an existing patient contacts the gynecologist’s office to ask a question or determine if an office visit is necessary, the gynecologist may bill for it using code G2012.

E-visits. Established Medicare patients may have non–face-to-face patient-initiated communications with their gynecologists without going to the physician’s office. These services can be billed only when the physician has an established relationship with the patient. The services may be billed using CPT codes 99421 to 99423. Coding for these visits is determined by the length of time the gynecologist spends online with the patient:

- 99421: Online digital evaluation and management service, for an established patient 5 to 10 minutes spent on the virtual visit

- 99422: 11 to 20 minutes

- 99423: ≥ 21 minutes.

Many clinicians want to immediately start the communication process with their patients. Many will avail themselves of the free video communication offered by Google Hangouts, Skype, Facetime, and Facebook Messenger. Since the March 15, 2020, relaxation of the HIPAA restrictions for telemedicine, it is now possible to have a virtual visit with a patient using one of the free, non–HIPAA-compliant connections. This type of visit is no different than a telephone call but with an added video component. Using these free technologies, a gynecologist can have an asynchronous visit with a patient (referred to as the store and forward method of sending information or medical images), which means that the service takes place in one direction with no opportunity for interaction with the patient. Asynchronous visits are akin to video text messages left for the patient. By contrast, a synchronous or real-time video visit with a patient is a 2-way communication that provides medical care without examining the patient.

Using triangulation

There are some downsides to telemedicine visits. First, virtual visits on Skype, FaceTime, and other non–HIPAA-compliant methods are not conducted on an encrypted website. Second, no documentation is created for the doctor-patient encounter. Finally, unless the physician keeps a record of these virtual visits and submits the interactions to the practice coders, there will be no billing and no reimbursement for the visits. In this scenario, physicians are legally responsible for their decision-making, prescription writing, and medical advice, but do not receive compensation for their efforts.

This can be remedied by using “triangulation,” which involves: 1. the physician, 2. the patient, and 3. a scribe or medical assistant who will record the visit. Before initiating the virtual visit using triangulation, it is imperative to ask the patient for permission if your medical assistant (or any other person in the office who functions as a scribe) will be listening to the conversation. It is important to explain that the person is there to take accurate notes and ascertain that the notes are entered into the EHR. Also, the scribe or assistant will record the time, date, and duration of the visit, which is a requirement for billing purposes. The scribe may also ascertain that the visit is properly coded and entered into the practice management system, and that a bill is submitted to the insurance company. By using triangulation, you have documentation that consent was obtained, that the visit took place, that notes were taken, and that the patient’s insurance company will be billed for the visit (see FIGURE 2 for a sample documentation form).

Continue to: Which CPT codes should I use?...

Which CPT codes should I use?

The answer depends on a number of factors, but a good rule of thumb is to use the same codes that you would use for an in-person appointment (CPT codes 99211-99215 for an established patient visit and 99201-99205 for a new patient visit). These are the most common CPT codes for outpatient gynecologic office visits whether they take place face-to-face or as a synchronous virtual visit (via a real-time interactive audio and video telecommunications system).

For example, the reimbursement for code 99213 has a range from $73 to $100. You may wonder how you can achieve the complexity requirements for a level-3 office visit without a physical examination. Whether as a face-to-face or virtual visit, documentation for these encounters requires 2 of 3 of the following components:

- expanded problem-focused history

- expanded problem-focused exam (not accomplished with telemedicine)

- low-complexity medical decision-making OR

- at least 15 minutes spent face to face with the patient if coding is based on time.

If a gynecologist reviews the results of a recent lab test for an estrogen-deficient patient and adjusts the estrogen dosage, writes a prescription, and spends 15 minutes communicating with the patient, he/she has met the complexity requirements for a code 99213. Because Level 3 and 4 visits (99214 and 99215) require a comprehensive physical examination, it is necessary to document the time spent with the patient (code 99214 requires 25 to 39 minutes of consultation and code 99215 requires ≥ 40 minutes).

Some final billing and coding advice

Always confirm telemedicine billing guidelines before beginning to conduct telemedicine visits. Consider starting a phone call to a payer armed with the fact that the payer is required by law to offer parity between telemedicine and face-to-face visits. Then ask which specific billing codes should be used.

Until you and your practice become comfortable with the process of, and the coding and billing for, telemedicine, consider using a telemedicine platform that has a built-in rules engine that offers recommendations for each telemedicine visit based on past claims data. These systems help gynecologists determine which CPT code to use and which modifiers are appropriate for the various insurance companies. In other words, the rules engine helps you submit a clean claim that is less likely to be denied and very likely to be paid. There are some vendors who are so confident that their rules engine will match the service with the proper CPT code and modifier that they guarantee full private payer reimbursement for telemedicine visits, or the vendor will reimburse the claim.

Watch for the third and final installment in this series, which was written with the assistance of 2 attorneys. It will review the legal guidelines for implementing telemedicine in a gynecologic practice and discuss the future of the technology. ●

- COVID-19 and Telehealth Coding Options as of March 20, 2020. https://www.ismanet.org/pdf/COVID-19andTelehealthcodes3-20-2020Updates.pdf.

- Federation of State Medical Boards. US States and Territories Modifying Licensure Requirements for Physicians in Response to COVID-19. Last updated May 26, 2020. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/pdf/state-emergency-declarations-licensures-requirementscovid-19.pdf.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Current State Laws and Reimbursement Policies https://www.cchpca.org/telehealth-policy/current-state-laws-and-reimbursement-policies.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. Updated April 30, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicinein practice. Updated May 22, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine-practice.

- Eddy N. Patients increasingly trusting of remote care technology. Healthcare IT News. October 22, 2019. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/patients-increasingly-trusting-remote-care-technology-says-new-report. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Welch BM, Harvey J, O’Connell NS, et al. Patient preferences for direct-to-consumer telemedicine services: a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:784.

- Tsai JM, Cheng MJ, Tsai HH, et al. Acceptance and resistance of telehealth: the perspective of dual-factor concepts in technology adoption. Int J Inform Manag. 2019;49:34-44.

- Hollander J, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679-1681.

- Pew Research Center. Internet and Technology. Mobile Fact Sheet. June 12, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org /internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicine in practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/ practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine- practice. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Federal and state regulation updates. https://www.cchpca.org. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- The White House. Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) outbreak. March 13, 2020. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Quick glance state telehealth actions in response to COVID-19. https://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/STATE%20TELEHEALTH%20ACTIONS%20IN%20RESPONSE%20TO%20COVID%20

OVERVIEW%205.5.2020_0.pdf. AccessedMay 13, 2020. - Medicare.gov. https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change -plans/types-of-medicare-health-plans/medicare-advantage-plans/how-do-medicare-advantage-plans-work. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS finalizes policies to bring innovative telehealth benefit to Medicare Advantage. April 5, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom /press-releases/cms-finalizes-policies-bring-innovative-telehealth-benefit-medicare-advantage. Accessed May 18,2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telehealth frequently asked questions. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-telehealth-frequently-asked-questions-faqs-31720.pdf.

- American Hospital Association. Coronavirus update: CMS broadens access to telehealth during Covid-19 public health emergency. https://www.aha.org/advisory/2020-03-17-coronavirus-update-cms-broadens-access-telehealth-during-covid-19-public-health. Accessed May 18, 2020.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, many significant changes have occurred that have made the implementation of telemedicine easier and more attractive for gynecologic practices. In the first article in this series, we discussed the benefits of telemedicine to physicians and patients, how to get started using telemedicine, and implementing a workflow. This article will discuss the common hurdles in the process and the proper coding to use to insure reimbursement for services rendered.

Barriers to implementing telemedicine

Incorrect assumptions

Latecomers to telemedicine often assume that patients prefer face-to-face visits when, in fact, many may prefer the convenience of virtual visits. More than 50% of patients who are surveyed about their experience with telemedicine say that online tools have helped improve their relationship with their providers.1 Telemedicine has grown astronomically during the COVID-19 pandemic to the point where many patients now expect their health care providers to be able to conduct virtual visits. Practices that do not offer telemedicine may find their patients seeking services elsewhere. Nearly two-thirds of health care professionals expect their commitment to telemedicine to increase significantly in the next 3 years.2 Of those providers who have not yet adopted the practice, nearly 85% expect to implement telemedicine in the near future.3 COVID-19 has motivated the increased use of telemedicine to enhance the communication with patients, making it possible for patients to have enhanced access to health care during this pandemic while minimizing infectious transmission of COVID-19 to physicians and their staff.4

Admittedly, telemedicine is not appropriate for all patients. In general, situations that do not lend themselves to telemedicine are those for which an in-person visit is required to evaluate the patient via a physical examination, to perform a protocol-driven procedure, or provide an aggressive intervention. Additional patients for whom telemedicine may be inappropriate include those with cognitive disorders, those with language barriers, those with emergency situations that warrant an office visit or a visit to the emergency department, and patients who do not have access to the technology to conduct a virtual visit.