User login

Barriers to Early Hospital Discharge: A Cross-Sectional Study at Five Academic Hospitals

Hospital discharges frequently occur in the afternoon or evening hours.1-5 Late discharges can adversely affect patient flow throughout the hospital,3,6-9 which, in turn, can result in delays in care,10-16 more medication errors,17 increased mortality,18-20 longer lengths of stay,20-22 higher costs,23 and lower patient satisfaction.24

Various interventions have been employed in the attempts to find ways of moving discharge times to earlier in the day, including preparing the discharge paperwork and medications the previous night,25 using checklists,1,25 team huddles,2 providing real-time feedback to unit staff,1 and employing multidisciplinary teamwork.1,2,6,25,26

The purpose of this study was to identify and determine the relative frequency of barriers to writing discharge orders in the hopes of identifying issues that might be addressed by targeted interventions. We also assessed the effects of daily team census, patients being on teaching versus nonteaching services, and how daily rounds were structured at the time that the discharge orders were written.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a prospective, cross-sectional survey of house-staff and attending physicians on general medicine teaching and nonteaching services from November 13, 2014, through May 31, 2016. The study was conducted at the following five hospitals: Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC) and Presbyterian/Saint Luke’s Medical Center (PSL) in Denver, Colorado; Ronald Reagan University (UCLA) and Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center (LAC+USC) in Los Angeles, California; and Harborview Medical Center (HMC) in Seattle, Washington. The study was approved by the Colorado Multi-Institutional Review Board as well as by the review boards of the other participating sites.

Data Collection

The results of the focus groups composed of attending physicians at DHMC were used to develop our initial data collection template. Additional sites joining the study provided feedback, leading to modifications (Appendix 1).

Physicians were surveyed at three different time points on study days that were selected according to the convenience of the investigators. The sampling occurred only on weekdays and was done based on the investigators’ availability. Investigators would attempt to survey as many teams as they were able to but, secondary to feasibility, not all teams could be surveyed on study days. The specific time points varied as a function of physician workflows but were standardized as much as possible to occur in the early morning, around noon, and midafternoon on weekdays. Physicians were contacted either in person or by telephone for verbal consent prior to administering the first survey. All general medicine teams were eligible. For teaching teams, the order of contact was resident, intern, and then attending based on which physician was available at the time of the survey and on which member of the team was thought to know the patients the best. For the nonteaching services, the attending physicians were contacted.

During the initial survey, the investigators assessed the provider role (ie, attending or housestaff), whether the service was a teaching or a nonteaching service, and the starting patient census on that service primarily based on interviewing the provider of record for the team and looking at team census lists. Physicians were asked about their rounding style (ie, sickest patients first, patients likely to be discharged first, room-by-room, most recently admitted patients first, patients on the team the longest, or other) and then to identify all patients they thought would be definite discharges sometime during the day of the survey. Definite discharges were defined as patients whom the provider thought were either currently ready for discharge or who had only minor barriers that, if unresolved, would not prevent same-day discharge. They were asked if the discharge order had been entered and, if not, what was preventing them from doing so, if the discharge could in their opinion have occurred the day prior and, if so, why this did not occur. We also obtained the date and time of the admission and discharge orders, the actual discharge time, as well as the length of stay either through chart review (majority of sites) or from data warehouses (Denver Health and Presbyterian St. Lukes had length of stay data retrieved from their data warehouse).

Physicians were also asked to identify all patients whom they thought might possibly be discharged that day. Possible discharges were defined as patients with barriers to discharge that, if unresolved, would prevent same-day discharge. For each of these, the physicians were asked to list whatever issues needed to be resolved prior to placing the discharge order (Appendix 1).

The second survey was administered late morning on the same day, typically between 11

The third survey was administered midafternoon, typically around 3 PM similar to the first two surveys, with the exception that the third survey did not attempt to identify new definite or possible discharges.

Sample Size

We stopped collecting data after obtaining a convenience sample of 5% of total discharges at each study site or on the study end date, which was May 31, 2016, whichever came first.

Data Analysis

Data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based application electronic data capture tool (REDCap), hosted at Denver Health. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Nashville, Tennessee) is designed to support data collection for research studies.27 Data were then analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All data entered into REDCap were reviewed by the principal investigator to ensure that data were not missing, and when there were missing data, a query was sent to verify if the data were retrievable. If retrievable, then the data would be entered. The volume of missing data that remained is described in our results.

Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) based on tests of normality. Differences in the time that the discharge orders were placed in the electronic medical record according to morning patient census, teaching versus nonteaching service, and rounding style were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Linear regression was used to evaluate the effect of patient census on discharge order time. P < .05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

We conducted 1,584 patient evaluations through surveys of 254 physicians over 156 days. Given surveys coincided with the existing work we had full participation (ie, 100% participation) and no dropout during the study days. Median (IQR) survey time points were 8:30

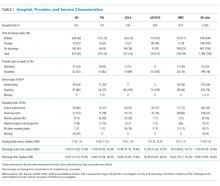

The characteristics of the five hospitals participating in the study, the patients’ final discharge status, the types of physicians surveyed, the services on which they were working, the rounding styles employed, and the median starting daily census are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the physicians surveyed were housestaff working on teaching services, and only a small minority structured rounds such that patients ready for discharge were seen first.

Over the course of the three surveys, 949 patients were identified as being definite discharges at any time point, and the large majority of these (863, 91%) were discharged on the day of the survey. The median (IQR) time that the discharge orders were written was 11:50

During the initial morning survey, 314 patients were identified as being definite discharges for that day (representing approximately 6% of the total number of patients being cared for, or 33% of the patients identified as definite discharges throughout the day). Of these, the physicians thought that 44 (<1% of the total number of patients being cared for on the services) could have been discharged on the previous day. The most frequent reasons cited for why these patients were not discharged on the previous day were “Patient did not want to leave” (n = 15, 34%), “Too late in the day” (n = 10, 23%), and “No ride” (n = 9, 20%). The remaining 10 patients (23%) had a variety of reasons related to system or social issues (ie, shelter not available, miscommunication).

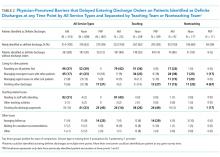

At the morning time point, the most common barriers to discharge identified were that the physicians had not finished rounding on their team of patients and that the housestaff needed to staff their patients with their attending. At noon, caring for other patients and tending to the discharge processes were most commonly cited, and in the afternoon, the most common barriers were that the physicians were in the process of completing the discharge paperwork for those patients or were discharging other patients (Table 2). When comparing barriers on teaching to nonteaching teams, a higher proportion of teaching teams were still rounding on all patients and were working on discharge paperwork at the second survey. Barriers cited by sites were similar; however, the frequency at which the barriers were mentioned varied (data not shown).

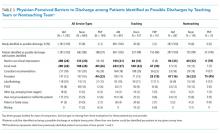

The physicians identified 1,237 patients at any time point as being possible discharges during the day of the survey and these had a mean (±SD) of 1.3 (±0.5) barriers cited for why these patients were possible rather than definite discharges. The most common were that clinical improvement was needed, one or more pending issues related to their care needed to be resolved, and/or awaiting pending test results. The need to see clinical improvement generally decreased throughout the day as did the need to staff patients with an attending physician, but barriers related to consultant recommendations or completing procedures increased (Table 3). Of the 1,237 patients ever identified as possible discharges, 594 (48%) became a definite discharge by the third call and 444 (36%) became a no discharge as their final status. As with definite discharges, barriers cited by sites were similar; however, the frequency at which the barriers were mentioned varied.

Among the 949 and 1,237 patients who were ever identified as definite or possible discharges, respectively, at any time point during the study day, 28 (3%) and 444 (36%), respectively, had their discharge status changed to no discharge, most commonly because their clinical condition either worsened or expected improvements did not occur or that barriers pertaining to social work, physical therapy, or occupational therapy were not resolved.

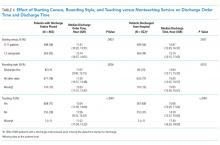

The median time that the discharge orders were entered into the electronic medical record was 43 minutes earlier if patients were on teams with a lower versus a higher starting census (P = .0003), 48 minutes earlier if they were seen by physicians whose rounding style was to see patients first who potentially could be discharged (P = .0026), and 58 minutes earlier if they were on nonteaching versus teaching services (P < .0001; Table 4). For every one-person increase in census, the discharge order time increased by 6 minutes (β = 5.6, SE = 1.6, P = .0003).

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that (1) the large majority of issues thought to delay discharging patients identified as definite discharges were related to physicians caring for other patients on their team, (2) although 91% of patients ever identified as being definite discharges were discharged on the day of the survey, only 48% of those identified as possible discharges became definite discharges by the afternoon time point, largely because the anticipated clinical improvement did not occur or care being provided by ancillary services had not been completed, and (3) discharge orders on patients identified as definite discharges were written on average 50 minutes earlier by physicians on teams with a smaller starting patient census, on nonteaching services, or when the rounding style was to see patients ready for discharges first.

Previous research has reported that physician-perceived barriers to discharge were extrinsic to providers and even extrinsic to the hospital setting (eg, awaiting subacute nursing placement and transportation).28,29 However, many of the barriers that we identified were related directly to the providers’ workload and rounding styles and whether the patients were on teaching versus nonteaching services. We also found that delays in the ability of hospital services to complete care also contributed to delayed discharges.

Our observational data suggest that delays resulting from caring for other patients might be reduced by changing rounding styles such that patients ready for discharge are seen first and are discharged prior to seeing other patients on the team, as previously reported by Beck et al.30 Intuitively, this would seem to be a straightforward way of freeing up beds earlier in the day, but such a change will, of necessity, lead to delaying care for other patients, which, in turn, could increase their length of stays. Durvasula et al. suggested that discharges could be moved to earlier in the day by completing orders and paperwork the day prior to discharge.25 Such an approach might be effective on an Obstetrical or elective Orthopedic service on which patients predictably are hospitalized for a fixed number of days (or even hours) but may be less relevant to patients on internal medicine services where lengths of stay are less predictable. Interventions to improve discharge times have resulted in earlier discharge times in some studies,2,4 but the overall length of stay either did not decrease25 or increased31 in others. Werthheimer et al.1 did find earlier discharge times, but other interventions also occurred during the study period (eg, extending social work services to include weekends).1,32

We found that discharge times were approximately 50 minutes earlier on teams with a smaller starting census, on nonteaching compared with teaching services, or when the attending’s rounding style was to see patients ready for discharges first. Although 50 minutes may seem like a small change in discharge time, Khanna et al.33 found that when discharges occur even 1 hour earlier, hospital overcrowding is reduced. To have a lower team census would require having more teams and more providers to staff these teams, raising cost-effectiveness concerns. Moving to more nonteaching services could represent a conflict with respect to one of the missions of teaching hospitals and raises a cost-benefit issue as several teaching hospitals receive substantial funding in support of their teaching activities and housestaff would have to be replaced with more expensive providers.

Delays attributable to ancillary services indicate imbalances between demand and availability of these services. Inappropriate demand and inefficiencies could be reduced by systems redesign, but in at least some instances, additional resources will be needed to add staff, increase space, or add additional equipment.

Our study has several limitations. First, we surveyed only physicians working in university-affiliated hospitals, and three of these were public safety-net hospitals. Accordingly, our results may not be generalizable to different patient populations. Second, we surveyed only physicians, and Minichiello et al.29 found that barriers to discharge perceived by physicians were different from those of other staff. Third, our data were observational and were collected only on weekdays. Fourth, we did not differentiate interns from residents, and thus, potentially the level of training could have affected these results. Similarly, the decision for a “possible” and a “definite” discharge is likely dependent on the knowledge base of the participant, such that less experienced participants may have had differing perspectives than someone with more experience. Fifth, the sites did vary based on the infrastructure and support but also had several similarities. All sites had social work and case management involved in care, although at some sites, they were assigned according to team and at others according to geographic location. Similarly, rounding times varied. Most of the services surveyed did not utilize advanced practice providers (the exception was the nonteaching services at Denver Health, and their presence was variable). These differences in staffing models could also have affected these results.

Our study also has a number of strengths. First, we assessed the barriers at five different hospitals. Second, we collected real-time data related to specific barriers at multiple time points throughout the day, allowing us to assess the dynamic nature of identifying patients as being ready or nearly ready for discharge. Third, we assessed the perceptions of barriers to discharge from physicians working on teaching as well as nonteaching services and from physicians utilizing a variety of rounding styles. Fourth, we had a very high participation rate (100%), probably due to the fact that our study was strategically aligned with participants’ daily work activities.

In conclusion, we found two distinct categories of issues that physicians perceived as most commonly delaying writing discharge orders on their patients. The first pertained to patients thought to definitely be ready for discharge and was related to the physicians having to care for other patients on their team. The second pertained to patients identified as possibly ready for discharge and was related to the need for care to be completed by a variety of ancillary services. Addressing each of these barriers would require different interventions and a need to weigh the potential improvements that could be achieved against the increased costs and/or delays in care for other patients that may result.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

1. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

2. Kane M, Weinacker A, Arthofer R, et al. A multidisciplinary initiative to increase inpatient discharges before noon. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46(12):630-635. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000418. PubMed

3. Khanna S, Sier D, Boyle J, Zeitz K. Discharge timeliness and its impact on hospital crowding and emergency department flow performance. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(2):164-170. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12543. PubMed

4. Kravet SJ, Levine RB, Rubin HR, Wright SM. Discharging patients earlier in the day: a concept worth evaluating. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2007;26:142-146. doi: 10.1097/01.HCM.0000268617.33491.60. PubMed

5. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Impact of admission and discharge peak times on hospital overcrowding. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;168:82-88. doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-791-8-82. PubMed

6. McGowan JE, Truwit JD, Cipriano P, et al. Operating room efficiency and hospital capacity: factors affecting operating room use during maximum hospital census. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(5):865-871; discussion 71-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.052 PubMed

7. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Early discharge and its effect on ED length of stay and access block. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;178:92-98. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-078-9-92 PubMed

8. Powell ES, Khare RK, Venkatesh AK, Van Roo BD, Adams JG, Reinhardt G. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(2):186-196. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.028. PubMed

9. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Iturrate E, Bailey M, Hochman K. Discharge before noon: Effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664-669. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2412. PubMed

10. Sikka R, Mehta S, Kaucky C, Kulstad EB. ED crowding is associated with an increased time to pneumonia treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(7):809-812. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.06.023. PubMed

11. Coil CJ, Flood JD, Belyeu BM, Young P, Kaji AH, Lewis RJ. The effect of emergency department boarding on order completion. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:730-736 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.09.018. PubMed

12. Gaieski DF, Agarwal AK, Mikkelsen ME, et al. The impact of ED crowding on early interventions and mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:953-960. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.01.061. PubMed

13. Pines JM, Localio AR, Hollander JE, et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510-516. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.021. PubMed

14. Hwang U, Richardson L, Livote E, Harris B, Spencer N, Sean Morrison R. Emergency department crowding and decreased quality of pain care. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1248-1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00267.x. PubMed

15. Mills AM, Shofer FS, Chen EH, Hollander JE, Pines JM. The association between emergency department crowding and analgesia administration in acute abdominal pain patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:603-608. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00441.x. PubMed

16. Pines JM, Shofer FS, Isserman JA, Abbuhl SB, Mills AM. The effect of emergency department crowding on analgesia in patients with back pain in two hospitals. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(3):276-283. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00676.x. PubMed

17. Kulstad EB, Sikka R, Sweis RT, Kelley KM, Rzechula KH. ED overcrowding is associated with an increased frequency of medication errors. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:304-309. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.014. PubMed

18. Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006;184(5):213-216. PubMed

19. Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(2):126-136. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014. PubMed

20. Singer AJ, Thode HC, Jr., Viccellio P, Pines JM. The association between length of emergency department boarding and mortality. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(12):1324-1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01236.x. PubMed

21. White BA, Biddinger PD, Chang Y, Grabowski B, Carignan S, Brown DF. Boarding inpatients in the emergency department increases discharged patient length of stay. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):230-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.007. PubMed

22. Forster AJ, Stiell I, Wells G, Lee AJ, van Walraven C. The effect of hospital occupancy on emergency department length of stay and patient disposition. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(2):127-133. doi: 10.1197/aemj.10.2.127. PubMed

23. Foley M, Kifaieh N, Mallon WK. Financial impact of emergency department crowding. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(2):192-197. PubMed

24. Pines JM, Iyer S, Disbot M, Hollander JE, Shofer FS, Datner EM. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient satisfaction for admitted patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(9):825-831. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00200.x. PubMed

25. Durvasula R, Kayihan A, Del Bene S, et al. A multidisciplinary care pathway significantly increases the number of early morning discharges in a large academic medical center. Qual Manag Health Care. 2015;24:45-51. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000049. PubMed

26. Cho HJ, Desai N, Florendo A, et al. E-DIP: Early Discharge Project. A Model for Throughput and Early Discharge for 1-Day Admissions. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1): pii: u210035.w4128. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u210035.w4128. PubMed

27. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. PubMed

28. Patel H, Fang MC, Mourad M, et al. Hospitalist and internal medicine leaders’ perspectives of early discharge challenges at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):388-391. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2885. PubMed

29. Minichiello TM, Auerbach AD, Wachter RM. Caregiver perceptions of the reasons for delayed hospital discharge. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):250-255. PubMed

30. Beck MJ, Okerblom D, Kumar A, Bandyopadhyay S, Scalzi LV. Lean intervention improves patient discharge times, improves emergency department throughput and reduces congestion. Hosp Pract (1995). 2016;44(5):252-259. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2016.1254559. PubMed

31. Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):859-861. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2529. PubMed

32. Shine D. Discharge before noon: an urban legend. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):445-446. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.011. PubMed 33. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Unravelling relationships: Hospital occupancy levels, discharge timing and emergency department access block. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(5):510-517. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01587.x. PubMed

33. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Unravelling relationships: Hospital occupancy levels, discharge timing and emergency department access block. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(5):510-517. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01587.x. PubMed

Hospital discharges frequently occur in the afternoon or evening hours.1-5 Late discharges can adversely affect patient flow throughout the hospital,3,6-9 which, in turn, can result in delays in care,10-16 more medication errors,17 increased mortality,18-20 longer lengths of stay,20-22 higher costs,23 and lower patient satisfaction.24

Various interventions have been employed in the attempts to find ways of moving discharge times to earlier in the day, including preparing the discharge paperwork and medications the previous night,25 using checklists,1,25 team huddles,2 providing real-time feedback to unit staff,1 and employing multidisciplinary teamwork.1,2,6,25,26

The purpose of this study was to identify and determine the relative frequency of barriers to writing discharge orders in the hopes of identifying issues that might be addressed by targeted interventions. We also assessed the effects of daily team census, patients being on teaching versus nonteaching services, and how daily rounds were structured at the time that the discharge orders were written.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a prospective, cross-sectional survey of house-staff and attending physicians on general medicine teaching and nonteaching services from November 13, 2014, through May 31, 2016. The study was conducted at the following five hospitals: Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC) and Presbyterian/Saint Luke’s Medical Center (PSL) in Denver, Colorado; Ronald Reagan University (UCLA) and Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center (LAC+USC) in Los Angeles, California; and Harborview Medical Center (HMC) in Seattle, Washington. The study was approved by the Colorado Multi-Institutional Review Board as well as by the review boards of the other participating sites.

Data Collection

The results of the focus groups composed of attending physicians at DHMC were used to develop our initial data collection template. Additional sites joining the study provided feedback, leading to modifications (Appendix 1).

Physicians were surveyed at three different time points on study days that were selected according to the convenience of the investigators. The sampling occurred only on weekdays and was done based on the investigators’ availability. Investigators would attempt to survey as many teams as they were able to but, secondary to feasibility, not all teams could be surveyed on study days. The specific time points varied as a function of physician workflows but were standardized as much as possible to occur in the early morning, around noon, and midafternoon on weekdays. Physicians were contacted either in person or by telephone for verbal consent prior to administering the first survey. All general medicine teams were eligible. For teaching teams, the order of contact was resident, intern, and then attending based on which physician was available at the time of the survey and on which member of the team was thought to know the patients the best. For the nonteaching services, the attending physicians were contacted.

During the initial survey, the investigators assessed the provider role (ie, attending or housestaff), whether the service was a teaching or a nonteaching service, and the starting patient census on that service primarily based on interviewing the provider of record for the team and looking at team census lists. Physicians were asked about their rounding style (ie, sickest patients first, patients likely to be discharged first, room-by-room, most recently admitted patients first, patients on the team the longest, or other) and then to identify all patients they thought would be definite discharges sometime during the day of the survey. Definite discharges were defined as patients whom the provider thought were either currently ready for discharge or who had only minor barriers that, if unresolved, would not prevent same-day discharge. They were asked if the discharge order had been entered and, if not, what was preventing them from doing so, if the discharge could in their opinion have occurred the day prior and, if so, why this did not occur. We also obtained the date and time of the admission and discharge orders, the actual discharge time, as well as the length of stay either through chart review (majority of sites) or from data warehouses (Denver Health and Presbyterian St. Lukes had length of stay data retrieved from their data warehouse).

Physicians were also asked to identify all patients whom they thought might possibly be discharged that day. Possible discharges were defined as patients with barriers to discharge that, if unresolved, would prevent same-day discharge. For each of these, the physicians were asked to list whatever issues needed to be resolved prior to placing the discharge order (Appendix 1).

The second survey was administered late morning on the same day, typically between 11

The third survey was administered midafternoon, typically around 3 PM similar to the first two surveys, with the exception that the third survey did not attempt to identify new definite or possible discharges.

Sample Size

We stopped collecting data after obtaining a convenience sample of 5% of total discharges at each study site or on the study end date, which was May 31, 2016, whichever came first.

Data Analysis

Data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based application electronic data capture tool (REDCap), hosted at Denver Health. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Nashville, Tennessee) is designed to support data collection for research studies.27 Data were then analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All data entered into REDCap were reviewed by the principal investigator to ensure that data were not missing, and when there were missing data, a query was sent to verify if the data were retrievable. If retrievable, then the data would be entered. The volume of missing data that remained is described in our results.

Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) based on tests of normality. Differences in the time that the discharge orders were placed in the electronic medical record according to morning patient census, teaching versus nonteaching service, and rounding style were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Linear regression was used to evaluate the effect of patient census on discharge order time. P < .05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

We conducted 1,584 patient evaluations through surveys of 254 physicians over 156 days. Given surveys coincided with the existing work we had full participation (ie, 100% participation) and no dropout during the study days. Median (IQR) survey time points were 8:30

The characteristics of the five hospitals participating in the study, the patients’ final discharge status, the types of physicians surveyed, the services on which they were working, the rounding styles employed, and the median starting daily census are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the physicians surveyed were housestaff working on teaching services, and only a small minority structured rounds such that patients ready for discharge were seen first.

Over the course of the three surveys, 949 patients were identified as being definite discharges at any time point, and the large majority of these (863, 91%) were discharged on the day of the survey. The median (IQR) time that the discharge orders were written was 11:50

During the initial morning survey, 314 patients were identified as being definite discharges for that day (representing approximately 6% of the total number of patients being cared for, or 33% of the patients identified as definite discharges throughout the day). Of these, the physicians thought that 44 (<1% of the total number of patients being cared for on the services) could have been discharged on the previous day. The most frequent reasons cited for why these patients were not discharged on the previous day were “Patient did not want to leave” (n = 15, 34%), “Too late in the day” (n = 10, 23%), and “No ride” (n = 9, 20%). The remaining 10 patients (23%) had a variety of reasons related to system or social issues (ie, shelter not available, miscommunication).

At the morning time point, the most common barriers to discharge identified were that the physicians had not finished rounding on their team of patients and that the housestaff needed to staff their patients with their attending. At noon, caring for other patients and tending to the discharge processes were most commonly cited, and in the afternoon, the most common barriers were that the physicians were in the process of completing the discharge paperwork for those patients or were discharging other patients (Table 2). When comparing barriers on teaching to nonteaching teams, a higher proportion of teaching teams were still rounding on all patients and were working on discharge paperwork at the second survey. Barriers cited by sites were similar; however, the frequency at which the barriers were mentioned varied (data not shown).

The physicians identified 1,237 patients at any time point as being possible discharges during the day of the survey and these had a mean (±SD) of 1.3 (±0.5) barriers cited for why these patients were possible rather than definite discharges. The most common were that clinical improvement was needed, one or more pending issues related to their care needed to be resolved, and/or awaiting pending test results. The need to see clinical improvement generally decreased throughout the day as did the need to staff patients with an attending physician, but barriers related to consultant recommendations or completing procedures increased (Table 3). Of the 1,237 patients ever identified as possible discharges, 594 (48%) became a definite discharge by the third call and 444 (36%) became a no discharge as their final status. As with definite discharges, barriers cited by sites were similar; however, the frequency at which the barriers were mentioned varied.

Among the 949 and 1,237 patients who were ever identified as definite or possible discharges, respectively, at any time point during the study day, 28 (3%) and 444 (36%), respectively, had their discharge status changed to no discharge, most commonly because their clinical condition either worsened or expected improvements did not occur or that barriers pertaining to social work, physical therapy, or occupational therapy were not resolved.

The median time that the discharge orders were entered into the electronic medical record was 43 minutes earlier if patients were on teams with a lower versus a higher starting census (P = .0003), 48 minutes earlier if they were seen by physicians whose rounding style was to see patients first who potentially could be discharged (P = .0026), and 58 minutes earlier if they were on nonteaching versus teaching services (P < .0001; Table 4). For every one-person increase in census, the discharge order time increased by 6 minutes (β = 5.6, SE = 1.6, P = .0003).

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that (1) the large majority of issues thought to delay discharging patients identified as definite discharges were related to physicians caring for other patients on their team, (2) although 91% of patients ever identified as being definite discharges were discharged on the day of the survey, only 48% of those identified as possible discharges became definite discharges by the afternoon time point, largely because the anticipated clinical improvement did not occur or care being provided by ancillary services had not been completed, and (3) discharge orders on patients identified as definite discharges were written on average 50 minutes earlier by physicians on teams with a smaller starting patient census, on nonteaching services, or when the rounding style was to see patients ready for discharges first.

Previous research has reported that physician-perceived barriers to discharge were extrinsic to providers and even extrinsic to the hospital setting (eg, awaiting subacute nursing placement and transportation).28,29 However, many of the barriers that we identified were related directly to the providers’ workload and rounding styles and whether the patients were on teaching versus nonteaching services. We also found that delays in the ability of hospital services to complete care also contributed to delayed discharges.

Our observational data suggest that delays resulting from caring for other patients might be reduced by changing rounding styles such that patients ready for discharge are seen first and are discharged prior to seeing other patients on the team, as previously reported by Beck et al.30 Intuitively, this would seem to be a straightforward way of freeing up beds earlier in the day, but such a change will, of necessity, lead to delaying care for other patients, which, in turn, could increase their length of stays. Durvasula et al. suggested that discharges could be moved to earlier in the day by completing orders and paperwork the day prior to discharge.25 Such an approach might be effective on an Obstetrical or elective Orthopedic service on which patients predictably are hospitalized for a fixed number of days (or even hours) but may be less relevant to patients on internal medicine services where lengths of stay are less predictable. Interventions to improve discharge times have resulted in earlier discharge times in some studies,2,4 but the overall length of stay either did not decrease25 or increased31 in others. Werthheimer et al.1 did find earlier discharge times, but other interventions also occurred during the study period (eg, extending social work services to include weekends).1,32

We found that discharge times were approximately 50 minutes earlier on teams with a smaller starting census, on nonteaching compared with teaching services, or when the attending’s rounding style was to see patients ready for discharges first. Although 50 minutes may seem like a small change in discharge time, Khanna et al.33 found that when discharges occur even 1 hour earlier, hospital overcrowding is reduced. To have a lower team census would require having more teams and more providers to staff these teams, raising cost-effectiveness concerns. Moving to more nonteaching services could represent a conflict with respect to one of the missions of teaching hospitals and raises a cost-benefit issue as several teaching hospitals receive substantial funding in support of their teaching activities and housestaff would have to be replaced with more expensive providers.

Delays attributable to ancillary services indicate imbalances between demand and availability of these services. Inappropriate demand and inefficiencies could be reduced by systems redesign, but in at least some instances, additional resources will be needed to add staff, increase space, or add additional equipment.

Our study has several limitations. First, we surveyed only physicians working in university-affiliated hospitals, and three of these were public safety-net hospitals. Accordingly, our results may not be generalizable to different patient populations. Second, we surveyed only physicians, and Minichiello et al.29 found that barriers to discharge perceived by physicians were different from those of other staff. Third, our data were observational and were collected only on weekdays. Fourth, we did not differentiate interns from residents, and thus, potentially the level of training could have affected these results. Similarly, the decision for a “possible” and a “definite” discharge is likely dependent on the knowledge base of the participant, such that less experienced participants may have had differing perspectives than someone with more experience. Fifth, the sites did vary based on the infrastructure and support but also had several similarities. All sites had social work and case management involved in care, although at some sites, they were assigned according to team and at others according to geographic location. Similarly, rounding times varied. Most of the services surveyed did not utilize advanced practice providers (the exception was the nonteaching services at Denver Health, and their presence was variable). These differences in staffing models could also have affected these results.

Our study also has a number of strengths. First, we assessed the barriers at five different hospitals. Second, we collected real-time data related to specific barriers at multiple time points throughout the day, allowing us to assess the dynamic nature of identifying patients as being ready or nearly ready for discharge. Third, we assessed the perceptions of barriers to discharge from physicians working on teaching as well as nonteaching services and from physicians utilizing a variety of rounding styles. Fourth, we had a very high participation rate (100%), probably due to the fact that our study was strategically aligned with participants’ daily work activities.

In conclusion, we found two distinct categories of issues that physicians perceived as most commonly delaying writing discharge orders on their patients. The first pertained to patients thought to definitely be ready for discharge and was related to the physicians having to care for other patients on their team. The second pertained to patients identified as possibly ready for discharge and was related to the need for care to be completed by a variety of ancillary services. Addressing each of these barriers would require different interventions and a need to weigh the potential improvements that could be achieved against the increased costs and/or delays in care for other patients that may result.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Hospital discharges frequently occur in the afternoon or evening hours.1-5 Late discharges can adversely affect patient flow throughout the hospital,3,6-9 which, in turn, can result in delays in care,10-16 more medication errors,17 increased mortality,18-20 longer lengths of stay,20-22 higher costs,23 and lower patient satisfaction.24

Various interventions have been employed in the attempts to find ways of moving discharge times to earlier in the day, including preparing the discharge paperwork and medications the previous night,25 using checklists,1,25 team huddles,2 providing real-time feedback to unit staff,1 and employing multidisciplinary teamwork.1,2,6,25,26

The purpose of this study was to identify and determine the relative frequency of barriers to writing discharge orders in the hopes of identifying issues that might be addressed by targeted interventions. We also assessed the effects of daily team census, patients being on teaching versus nonteaching services, and how daily rounds were structured at the time that the discharge orders were written.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a prospective, cross-sectional survey of house-staff and attending physicians on general medicine teaching and nonteaching services from November 13, 2014, through May 31, 2016. The study was conducted at the following five hospitals: Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC) and Presbyterian/Saint Luke’s Medical Center (PSL) in Denver, Colorado; Ronald Reagan University (UCLA) and Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center (LAC+USC) in Los Angeles, California; and Harborview Medical Center (HMC) in Seattle, Washington. The study was approved by the Colorado Multi-Institutional Review Board as well as by the review boards of the other participating sites.

Data Collection

The results of the focus groups composed of attending physicians at DHMC were used to develop our initial data collection template. Additional sites joining the study provided feedback, leading to modifications (Appendix 1).

Physicians were surveyed at three different time points on study days that were selected according to the convenience of the investigators. The sampling occurred only on weekdays and was done based on the investigators’ availability. Investigators would attempt to survey as many teams as they were able to but, secondary to feasibility, not all teams could be surveyed on study days. The specific time points varied as a function of physician workflows but were standardized as much as possible to occur in the early morning, around noon, and midafternoon on weekdays. Physicians were contacted either in person or by telephone for verbal consent prior to administering the first survey. All general medicine teams were eligible. For teaching teams, the order of contact was resident, intern, and then attending based on which physician was available at the time of the survey and on which member of the team was thought to know the patients the best. For the nonteaching services, the attending physicians were contacted.

During the initial survey, the investigators assessed the provider role (ie, attending or housestaff), whether the service was a teaching or a nonteaching service, and the starting patient census on that service primarily based on interviewing the provider of record for the team and looking at team census lists. Physicians were asked about their rounding style (ie, sickest patients first, patients likely to be discharged first, room-by-room, most recently admitted patients first, patients on the team the longest, or other) and then to identify all patients they thought would be definite discharges sometime during the day of the survey. Definite discharges were defined as patients whom the provider thought were either currently ready for discharge or who had only minor barriers that, if unresolved, would not prevent same-day discharge. They were asked if the discharge order had been entered and, if not, what was preventing them from doing so, if the discharge could in their opinion have occurred the day prior and, if so, why this did not occur. We also obtained the date and time of the admission and discharge orders, the actual discharge time, as well as the length of stay either through chart review (majority of sites) or from data warehouses (Denver Health and Presbyterian St. Lukes had length of stay data retrieved from their data warehouse).

Physicians were also asked to identify all patients whom they thought might possibly be discharged that day. Possible discharges were defined as patients with barriers to discharge that, if unresolved, would prevent same-day discharge. For each of these, the physicians were asked to list whatever issues needed to be resolved prior to placing the discharge order (Appendix 1).

The second survey was administered late morning on the same day, typically between 11

The third survey was administered midafternoon, typically around 3 PM similar to the first two surveys, with the exception that the third survey did not attempt to identify new definite or possible discharges.

Sample Size

We stopped collecting data after obtaining a convenience sample of 5% of total discharges at each study site or on the study end date, which was May 31, 2016, whichever came first.

Data Analysis

Data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based application electronic data capture tool (REDCap), hosted at Denver Health. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Nashville, Tennessee) is designed to support data collection for research studies.27 Data were then analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All data entered into REDCap were reviewed by the principal investigator to ensure that data were not missing, and when there were missing data, a query was sent to verify if the data were retrievable. If retrievable, then the data would be entered. The volume of missing data that remained is described in our results.

Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) based on tests of normality. Differences in the time that the discharge orders were placed in the electronic medical record according to morning patient census, teaching versus nonteaching service, and rounding style were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Linear regression was used to evaluate the effect of patient census on discharge order time. P < .05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

We conducted 1,584 patient evaluations through surveys of 254 physicians over 156 days. Given surveys coincided with the existing work we had full participation (ie, 100% participation) and no dropout during the study days. Median (IQR) survey time points were 8:30

The characteristics of the five hospitals participating in the study, the patients’ final discharge status, the types of physicians surveyed, the services on which they were working, the rounding styles employed, and the median starting daily census are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the physicians surveyed were housestaff working on teaching services, and only a small minority structured rounds such that patients ready for discharge were seen first.

Over the course of the three surveys, 949 patients were identified as being definite discharges at any time point, and the large majority of these (863, 91%) were discharged on the day of the survey. The median (IQR) time that the discharge orders were written was 11:50

During the initial morning survey, 314 patients were identified as being definite discharges for that day (representing approximately 6% of the total number of patients being cared for, or 33% of the patients identified as definite discharges throughout the day). Of these, the physicians thought that 44 (<1% of the total number of patients being cared for on the services) could have been discharged on the previous day. The most frequent reasons cited for why these patients were not discharged on the previous day were “Patient did not want to leave” (n = 15, 34%), “Too late in the day” (n = 10, 23%), and “No ride” (n = 9, 20%). The remaining 10 patients (23%) had a variety of reasons related to system or social issues (ie, shelter not available, miscommunication).

At the morning time point, the most common barriers to discharge identified were that the physicians had not finished rounding on their team of patients and that the housestaff needed to staff their patients with their attending. At noon, caring for other patients and tending to the discharge processes were most commonly cited, and in the afternoon, the most common barriers were that the physicians were in the process of completing the discharge paperwork for those patients or were discharging other patients (Table 2). When comparing barriers on teaching to nonteaching teams, a higher proportion of teaching teams were still rounding on all patients and were working on discharge paperwork at the second survey. Barriers cited by sites were similar; however, the frequency at which the barriers were mentioned varied (data not shown).

The physicians identified 1,237 patients at any time point as being possible discharges during the day of the survey and these had a mean (±SD) of 1.3 (±0.5) barriers cited for why these patients were possible rather than definite discharges. The most common were that clinical improvement was needed, one or more pending issues related to their care needed to be resolved, and/or awaiting pending test results. The need to see clinical improvement generally decreased throughout the day as did the need to staff patients with an attending physician, but barriers related to consultant recommendations or completing procedures increased (Table 3). Of the 1,237 patients ever identified as possible discharges, 594 (48%) became a definite discharge by the third call and 444 (36%) became a no discharge as their final status. As with definite discharges, barriers cited by sites were similar; however, the frequency at which the barriers were mentioned varied.

Among the 949 and 1,237 patients who were ever identified as definite or possible discharges, respectively, at any time point during the study day, 28 (3%) and 444 (36%), respectively, had their discharge status changed to no discharge, most commonly because their clinical condition either worsened or expected improvements did not occur or that barriers pertaining to social work, physical therapy, or occupational therapy were not resolved.

The median time that the discharge orders were entered into the electronic medical record was 43 minutes earlier if patients were on teams with a lower versus a higher starting census (P = .0003), 48 minutes earlier if they were seen by physicians whose rounding style was to see patients first who potentially could be discharged (P = .0026), and 58 minutes earlier if they were on nonteaching versus teaching services (P < .0001; Table 4). For every one-person increase in census, the discharge order time increased by 6 minutes (β = 5.6, SE = 1.6, P = .0003).

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study are that (1) the large majority of issues thought to delay discharging patients identified as definite discharges were related to physicians caring for other patients on their team, (2) although 91% of patients ever identified as being definite discharges were discharged on the day of the survey, only 48% of those identified as possible discharges became definite discharges by the afternoon time point, largely because the anticipated clinical improvement did not occur or care being provided by ancillary services had not been completed, and (3) discharge orders on patients identified as definite discharges were written on average 50 minutes earlier by physicians on teams with a smaller starting patient census, on nonteaching services, or when the rounding style was to see patients ready for discharges first.

Previous research has reported that physician-perceived barriers to discharge were extrinsic to providers and even extrinsic to the hospital setting (eg, awaiting subacute nursing placement and transportation).28,29 However, many of the barriers that we identified were related directly to the providers’ workload and rounding styles and whether the patients were on teaching versus nonteaching services. We also found that delays in the ability of hospital services to complete care also contributed to delayed discharges.

Our observational data suggest that delays resulting from caring for other patients might be reduced by changing rounding styles such that patients ready for discharge are seen first and are discharged prior to seeing other patients on the team, as previously reported by Beck et al.30 Intuitively, this would seem to be a straightforward way of freeing up beds earlier in the day, but such a change will, of necessity, lead to delaying care for other patients, which, in turn, could increase their length of stays. Durvasula et al. suggested that discharges could be moved to earlier in the day by completing orders and paperwork the day prior to discharge.25 Such an approach might be effective on an Obstetrical or elective Orthopedic service on which patients predictably are hospitalized for a fixed number of days (or even hours) but may be less relevant to patients on internal medicine services where lengths of stay are less predictable. Interventions to improve discharge times have resulted in earlier discharge times in some studies,2,4 but the overall length of stay either did not decrease25 or increased31 in others. Werthheimer et al.1 did find earlier discharge times, but other interventions also occurred during the study period (eg, extending social work services to include weekends).1,32

We found that discharge times were approximately 50 minutes earlier on teams with a smaller starting census, on nonteaching compared with teaching services, or when the attending’s rounding style was to see patients ready for discharges first. Although 50 minutes may seem like a small change in discharge time, Khanna et al.33 found that when discharges occur even 1 hour earlier, hospital overcrowding is reduced. To have a lower team census would require having more teams and more providers to staff these teams, raising cost-effectiveness concerns. Moving to more nonteaching services could represent a conflict with respect to one of the missions of teaching hospitals and raises a cost-benefit issue as several teaching hospitals receive substantial funding in support of their teaching activities and housestaff would have to be replaced with more expensive providers.

Delays attributable to ancillary services indicate imbalances between demand and availability of these services. Inappropriate demand and inefficiencies could be reduced by systems redesign, but in at least some instances, additional resources will be needed to add staff, increase space, or add additional equipment.

Our study has several limitations. First, we surveyed only physicians working in university-affiliated hospitals, and three of these were public safety-net hospitals. Accordingly, our results may not be generalizable to different patient populations. Second, we surveyed only physicians, and Minichiello et al.29 found that barriers to discharge perceived by physicians were different from those of other staff. Third, our data were observational and were collected only on weekdays. Fourth, we did not differentiate interns from residents, and thus, potentially the level of training could have affected these results. Similarly, the decision for a “possible” and a “definite” discharge is likely dependent on the knowledge base of the participant, such that less experienced participants may have had differing perspectives than someone with more experience. Fifth, the sites did vary based on the infrastructure and support but also had several similarities. All sites had social work and case management involved in care, although at some sites, they were assigned according to team and at others according to geographic location. Similarly, rounding times varied. Most of the services surveyed did not utilize advanced practice providers (the exception was the nonteaching services at Denver Health, and their presence was variable). These differences in staffing models could also have affected these results.

Our study also has a number of strengths. First, we assessed the barriers at five different hospitals. Second, we collected real-time data related to specific barriers at multiple time points throughout the day, allowing us to assess the dynamic nature of identifying patients as being ready or nearly ready for discharge. Third, we assessed the perceptions of barriers to discharge from physicians working on teaching as well as nonteaching services and from physicians utilizing a variety of rounding styles. Fourth, we had a very high participation rate (100%), probably due to the fact that our study was strategically aligned with participants’ daily work activities.

In conclusion, we found two distinct categories of issues that physicians perceived as most commonly delaying writing discharge orders on their patients. The first pertained to patients thought to definitely be ready for discharge and was related to the physicians having to care for other patients on their team. The second pertained to patients identified as possibly ready for discharge and was related to the need for care to be completed by a variety of ancillary services. Addressing each of these barriers would require different interventions and a need to weigh the potential improvements that could be achieved against the increased costs and/or delays in care for other patients that may result.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

1. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

2. Kane M, Weinacker A, Arthofer R, et al. A multidisciplinary initiative to increase inpatient discharges before noon. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46(12):630-635. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000418. PubMed

3. Khanna S, Sier D, Boyle J, Zeitz K. Discharge timeliness and its impact on hospital crowding and emergency department flow performance. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(2):164-170. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12543. PubMed

4. Kravet SJ, Levine RB, Rubin HR, Wright SM. Discharging patients earlier in the day: a concept worth evaluating. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2007;26:142-146. doi: 10.1097/01.HCM.0000268617.33491.60. PubMed

5. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Impact of admission and discharge peak times on hospital overcrowding. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;168:82-88. doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-791-8-82. PubMed

6. McGowan JE, Truwit JD, Cipriano P, et al. Operating room efficiency and hospital capacity: factors affecting operating room use during maximum hospital census. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(5):865-871; discussion 71-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.052 PubMed

7. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Early discharge and its effect on ED length of stay and access block. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;178:92-98. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-078-9-92 PubMed

8. Powell ES, Khare RK, Venkatesh AK, Van Roo BD, Adams JG, Reinhardt G. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(2):186-196. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.028. PubMed

9. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Iturrate E, Bailey M, Hochman K. Discharge before noon: Effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664-669. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2412. PubMed

10. Sikka R, Mehta S, Kaucky C, Kulstad EB. ED crowding is associated with an increased time to pneumonia treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(7):809-812. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.06.023. PubMed

11. Coil CJ, Flood JD, Belyeu BM, Young P, Kaji AH, Lewis RJ. The effect of emergency department boarding on order completion. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:730-736 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.09.018. PubMed

12. Gaieski DF, Agarwal AK, Mikkelsen ME, et al. The impact of ED crowding on early interventions and mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:953-960. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.01.061. PubMed

13. Pines JM, Localio AR, Hollander JE, et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510-516. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.021. PubMed

14. Hwang U, Richardson L, Livote E, Harris B, Spencer N, Sean Morrison R. Emergency department crowding and decreased quality of pain care. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1248-1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00267.x. PubMed

15. Mills AM, Shofer FS, Chen EH, Hollander JE, Pines JM. The association between emergency department crowding and analgesia administration in acute abdominal pain patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:603-608. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00441.x. PubMed

16. Pines JM, Shofer FS, Isserman JA, Abbuhl SB, Mills AM. The effect of emergency department crowding on analgesia in patients with back pain in two hospitals. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(3):276-283. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00676.x. PubMed

17. Kulstad EB, Sikka R, Sweis RT, Kelley KM, Rzechula KH. ED overcrowding is associated with an increased frequency of medication errors. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:304-309. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.014. PubMed

18. Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006;184(5):213-216. PubMed

19. Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(2):126-136. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014. PubMed

20. Singer AJ, Thode HC, Jr., Viccellio P, Pines JM. The association between length of emergency department boarding and mortality. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(12):1324-1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01236.x. PubMed

21. White BA, Biddinger PD, Chang Y, Grabowski B, Carignan S, Brown DF. Boarding inpatients in the emergency department increases discharged patient length of stay. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):230-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.007. PubMed

22. Forster AJ, Stiell I, Wells G, Lee AJ, van Walraven C. The effect of hospital occupancy on emergency department length of stay and patient disposition. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(2):127-133. doi: 10.1197/aemj.10.2.127. PubMed

23. Foley M, Kifaieh N, Mallon WK. Financial impact of emergency department crowding. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(2):192-197. PubMed

24. Pines JM, Iyer S, Disbot M, Hollander JE, Shofer FS, Datner EM. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient satisfaction for admitted patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(9):825-831. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00200.x. PubMed

25. Durvasula R, Kayihan A, Del Bene S, et al. A multidisciplinary care pathway significantly increases the number of early morning discharges in a large academic medical center. Qual Manag Health Care. 2015;24:45-51. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000049. PubMed

26. Cho HJ, Desai N, Florendo A, et al. E-DIP: Early Discharge Project. A Model for Throughput and Early Discharge for 1-Day Admissions. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1): pii: u210035.w4128. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u210035.w4128. PubMed

27. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. PubMed

28. Patel H, Fang MC, Mourad M, et al. Hospitalist and internal medicine leaders’ perspectives of early discharge challenges at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):388-391. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2885. PubMed

29. Minichiello TM, Auerbach AD, Wachter RM. Caregiver perceptions of the reasons for delayed hospital discharge. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):250-255. PubMed

30. Beck MJ, Okerblom D, Kumar A, Bandyopadhyay S, Scalzi LV. Lean intervention improves patient discharge times, improves emergency department throughput and reduces congestion. Hosp Pract (1995). 2016;44(5):252-259. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2016.1254559. PubMed

31. Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):859-861. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2529. PubMed

32. Shine D. Discharge before noon: an urban legend. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):445-446. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.011. PubMed 33. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Unravelling relationships: Hospital occupancy levels, discharge timing and emergency department access block. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(5):510-517. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01587.x. PubMed

33. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Unravelling relationships: Hospital occupancy levels, discharge timing and emergency department access block. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(5):510-517. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01587.x. PubMed

1. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

2. Kane M, Weinacker A, Arthofer R, et al. A multidisciplinary initiative to increase inpatient discharges before noon. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46(12):630-635. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000418. PubMed

3. Khanna S, Sier D, Boyle J, Zeitz K. Discharge timeliness and its impact on hospital crowding and emergency department flow performance. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(2):164-170. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12543. PubMed

4. Kravet SJ, Levine RB, Rubin HR, Wright SM. Discharging patients earlier in the day: a concept worth evaluating. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2007;26:142-146. doi: 10.1097/01.HCM.0000268617.33491.60. PubMed

5. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Impact of admission and discharge peak times on hospital overcrowding. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;168:82-88. doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-791-8-82. PubMed

6. McGowan JE, Truwit JD, Cipriano P, et al. Operating room efficiency and hospital capacity: factors affecting operating room use during maximum hospital census. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(5):865-871; discussion 71-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.052 PubMed

7. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Early discharge and its effect on ED length of stay and access block. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;178:92-98. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-078-9-92 PubMed

8. Powell ES, Khare RK, Venkatesh AK, Van Roo BD, Adams JG, Reinhardt G. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(2):186-196. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.028. PubMed

9. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Iturrate E, Bailey M, Hochman K. Discharge before noon: Effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664-669. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2412. PubMed

10. Sikka R, Mehta S, Kaucky C, Kulstad EB. ED crowding is associated with an increased time to pneumonia treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(7):809-812. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.06.023. PubMed

11. Coil CJ, Flood JD, Belyeu BM, Young P, Kaji AH, Lewis RJ. The effect of emergency department boarding on order completion. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:730-736 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.09.018. PubMed

12. Gaieski DF, Agarwal AK, Mikkelsen ME, et al. The impact of ED crowding on early interventions and mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:953-960. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.01.061. PubMed

13. Pines JM, Localio AR, Hollander JE, et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510-516. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.021. PubMed

14. Hwang U, Richardson L, Livote E, Harris B, Spencer N, Sean Morrison R. Emergency department crowding and decreased quality of pain care. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1248-1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00267.x. PubMed

15. Mills AM, Shofer FS, Chen EH, Hollander JE, Pines JM. The association between emergency department crowding and analgesia administration in acute abdominal pain patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:603-608. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00441.x. PubMed

16. Pines JM, Shofer FS, Isserman JA, Abbuhl SB, Mills AM. The effect of emergency department crowding on analgesia in patients with back pain in two hospitals. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(3):276-283. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00676.x. PubMed

17. Kulstad EB, Sikka R, Sweis RT, Kelley KM, Rzechula KH. ED overcrowding is associated with an increased frequency of medication errors. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:304-309. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.014. PubMed

18. Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006;184(5):213-216. PubMed

19. Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(2):126-136. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014. PubMed

20. Singer AJ, Thode HC, Jr., Viccellio P, Pines JM. The association between length of emergency department boarding and mortality. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(12):1324-1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01236.x. PubMed

21. White BA, Biddinger PD, Chang Y, Grabowski B, Carignan S, Brown DF. Boarding inpatients in the emergency department increases discharged patient length of stay. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):230-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.007. PubMed

22. Forster AJ, Stiell I, Wells G, Lee AJ, van Walraven C. The effect of hospital occupancy on emergency department length of stay and patient disposition. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(2):127-133. doi: 10.1197/aemj.10.2.127. PubMed

23. Foley M, Kifaieh N, Mallon WK. Financial impact of emergency department crowding. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(2):192-197. PubMed

24. Pines JM, Iyer S, Disbot M, Hollander JE, Shofer FS, Datner EM. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient satisfaction for admitted patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(9):825-831. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00200.x. PubMed

25. Durvasula R, Kayihan A, Del Bene S, et al. A multidisciplinary care pathway significantly increases the number of early morning discharges in a large academic medical center. Qual Manag Health Care. 2015;24:45-51. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000049. PubMed

26. Cho HJ, Desai N, Florendo A, et al. E-DIP: Early Discharge Project. A Model for Throughput and Early Discharge for 1-Day Admissions. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1): pii: u210035.w4128. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u210035.w4128. PubMed

27. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. PubMed

28. Patel H, Fang MC, Mourad M, et al. Hospitalist and internal medicine leaders’ perspectives of early discharge challenges at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):388-391. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2885. PubMed

29. Minichiello TM, Auerbach AD, Wachter RM. Caregiver perceptions of the reasons for delayed hospital discharge. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):250-255. PubMed

30. Beck MJ, Okerblom D, Kumar A, Bandyopadhyay S, Scalzi LV. Lean intervention improves patient discharge times, improves emergency department throughput and reduces congestion. Hosp Pract (1995). 2016;44(5):252-259. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2016.1254559. PubMed

31. Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):859-861. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2529. PubMed

32. Shine D. Discharge before noon: an urban legend. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):445-446. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.011. PubMed 33. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Unravelling relationships: Hospital occupancy levels, discharge timing and emergency department access block. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(5):510-517. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01587.x. PubMed

33. Khanna S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Unravelling relationships: Hospital occupancy levels, discharge timing and emergency department access block. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(5):510-517. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01587.x. PubMed

Safety of MRI in patients with implantable cardiac devices

Clinical question: Is MRI safe for patients who have implanted ICD or pacemakers that have not been deemed to be “MRI conditional” by the Food and Drug Administration?

Background: The majority of patients with implantable cardiac devices have a clinical indication for MRI within 10 years. Devices that meet certain criteria specified by the Food and Drug Administration are not felt to pose any safety hazards and are deemed “MRI conditional.” Those that do not meet these criteria are referred to as “legacy” devices and are considered to be a contraindication to MRI by the FDA and device manufacturers. The majority of ICDs and pacemakers currently in use are legacy devices and access to MRI for patients who have these devices has been very limited. This study is the first large prospective study to evaluate the safety of an MRI protocol in patients with legacy ICDs and pacemakers.

Study design: Prospective nonrandomized study.

Setting: Single academic medical center.

Synopsis: During 2003-2015, 1,509 patients with ICDs (629 patients) and pacemakers (880 patients) were enrolled and underwent 2,103 MRI examinations supervised by either an electrophysiologist or a registered nurse with cardiac device programming experience.

Study outcomes included safety and device function immediately after MRI and change in device parameters both immediately after MRI and at long-term follow-up. The most important clinical adverse event that occurred was a reset of device to backup settings referred to as “power on reset” that occurred in nine examinations. Of these nine events, one was associated with mild physical discomfort, one led to device replacement, and one was associated with transient inhibition of pacing. Small changes in P- or R-wave amplitude and atrial or ventricular capture were noted at long-term follow-up. However, none of these were large enough to result in lead revision or device reprogramming. Notable limitations of this study include that it is a single-center study limiting its ability to be generalized and that nearly 20% of patients were lost to long term follow up.

Bottom line: When performed at an institution with an established safety protocol, MRI examinations in patients with legacy devices are not associated with clinically significant adverse safety events or changes in device function that require reprogramming. Multicenter studies are necessary to determine if these results can be generalizable.

Citation: Nazarian S et al. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac devices. N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 28;377(26):2555-64.

Dr. Scaletta is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: Is MRI safe for patients who have implanted ICD or pacemakers that have not been deemed to be “MRI conditional” by the Food and Drug Administration?