User login

COVID-19: Managing resource crunch and ethical challenges

COVID-19 has been a watershed event in medical history of epic proportions. With this fast-spreading pandemic stretching resources at health care institutions, practical considerations for management of a disease about which we are still learning has been a huge challenge.

Although many guidelines have been made available by medical societies and experts worldwide, there appear to be very few which throw light on management in a resource-poor setup. The hospitalist, as a front-line provider, is likely expected to lead the planning and management of resources in order to deliver appropriate care.

As per American Hospital Association data, there are 2,704 community hospitals that can deliver ICU care in the United States. There are 534,964 acute care beds with 96,596 ICU beds. Additionally, there are 25,157 step-down beds and 1,183 burn unit beds. Of the 2,704 hospitals, 74% are in metropolitan areas (> 50,000 population), 17% (464) are in micropolitan areas (10,000-49,999 population), and the remaining 9% (244) are in rural areas. Only 7% (36,453) of hospital beds and 5% (4715) of ICU beds are in micropolitan areas. Two percent of acute care hospital beds and 1% of ICU beds are in rural areas. Although the US has the highest per capita number of ICU beds in the world, this may not be sufficient as these are concentrated in highly populated metropolitan areas.

Infrastructure and human power resource augmentation will be important. Infrastructure can be ramped up by:

- Canceling elective procedures

- Using the operating room and perioperative room ventilators and beds

- Servicing and using older functioning hospitals, medical wards, and ventilators.

As ventilators are expected to be in short supply, while far from ideal, other resources may include using ventilators from the Strategic National Stockpile, renting from vendors, and using state-owned stockpiles. Use of non-invasive ventilators, such as CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), BiPAP (bi-level positive airway pressure), and HFNC (high-flow nasal cannula) may be considered in addition to full-featured ventilators. Rapidly manufacturing new ventilators with government direction is also being undertaken.

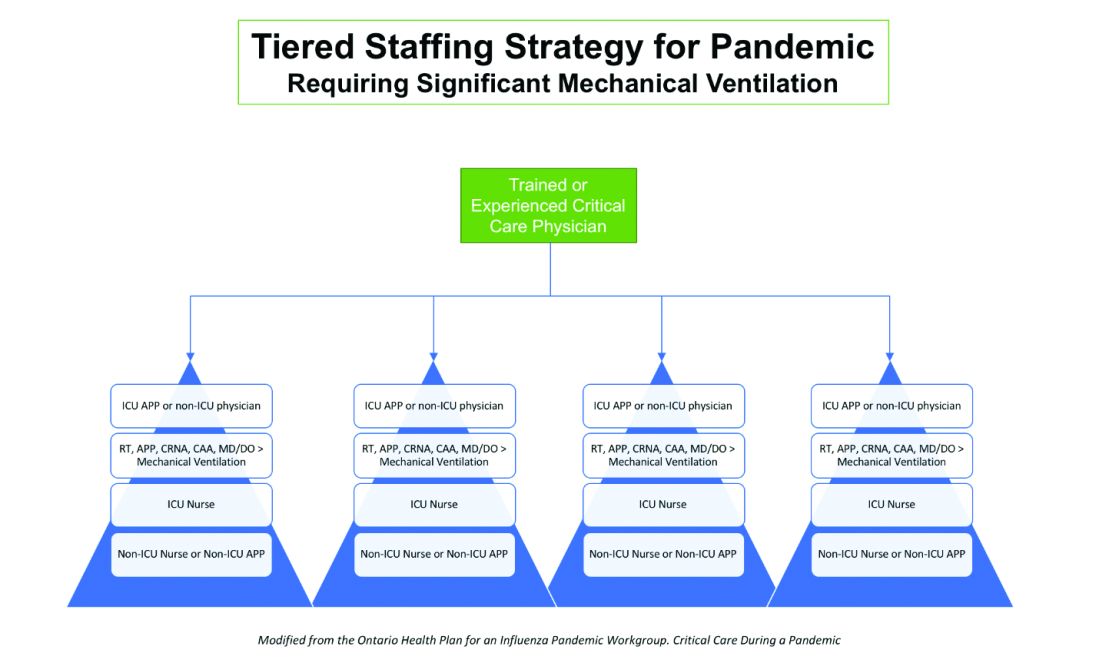

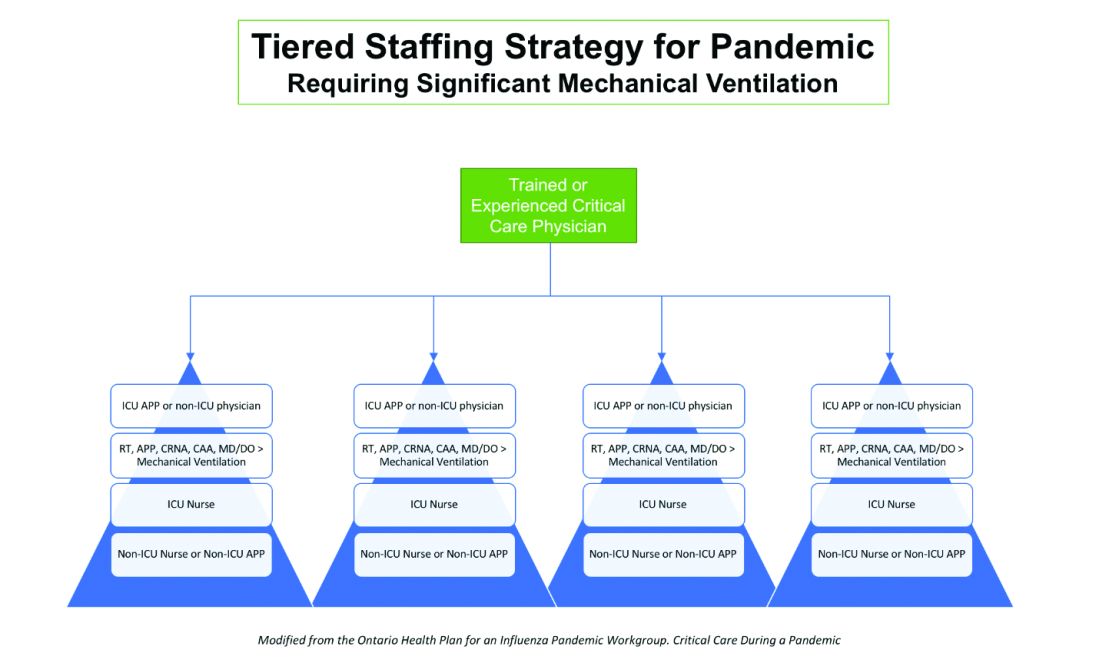

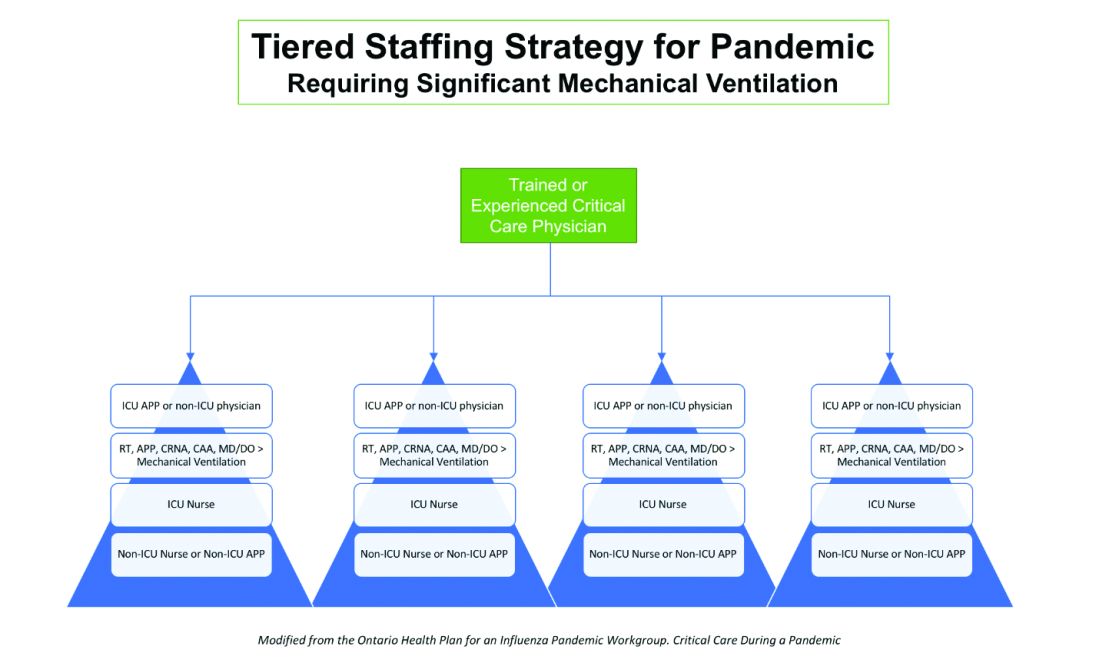

Although estimates vary based on the model used, about 1 million people are expected to need ventilatory support. However, in addition to infrastructural shortcomings, trained persons to care for these patients are lacking. Approximately 48% of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, and there are only 28,808 intensivists as per 2015 AHA data. In order to increase the amount of skilled manpower needed to staff ICUs, a model from the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Fundamental Disaster Management Program can be adopted. This involves an intensivist overseeing four different teams, with each team caring for 24 patients. Each team is led by a non-ICU physician or an ICU advanced practice provider (APP) who in turn cares for the patient with respiratory therapists, pharmacists, ICU nurses, and other non-ICU health professionals.

It is essential that infrastructure and human power be augmented and optimized, as well as contingency plans, including triage based on ethical and legal considerations, put in place if demand overwhelms capacity.

Lack of PPE and fear among health care staff

There have been widespread reports in the media, and several anecdotal reports, about severe shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), and as a result, an increase in fear and anxiety among frontline health care workers.

In addition, there also have been reports about hospital administrators disciplining medical and nursing staff for voicing their concerns about PPE shortages to the general public and the media. This likely stems from the narrow “optics” and public relations concerns of health care facilities.

It is evident that the size and magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic was grossly underestimated, and preparations were inadequate. But according to past surveys of health care workers, a good number of them believe that medical and nursing staff have a duty to deliver care to sick people even if it exposes them to personal danger.

Given the special skills and privileges that health care professionals possess, they do have a moral and ethical responsibility to take care of sick patients even if a danger to themselves exists. However, society also has a responsibility to provide for the safety of these health care workers by supplying them with appropriate safety gear. Given the unprecedented nature of this pandemic, it is obvious that federal and state governments, public health officials, and hospital administrators (along with health care professionals) are still learning how to appropriately respond to the challenge.

It would be reasonable and appropriate for everyone concerned to understand and acknowledge that there is a shortage of PPE, and while arranging for this to be replenished, undertake and implement measures that maximize the safety of all health care workers. An open forum, mutually agreed-upon policy and procedures, along with mechanisms to address concerns should be formulated.

In addition, health care workers who test positive for COVID-19 can be a source of infection for other health care workers and non-infected patients. Therefore, health care workers have the responsibility of reporting their symptoms, the right to have themselves tested, and they must follow agreed-upon procedures that would limit their ability to infect other people, including mandated absenteeism from work. Every individual has a right to safety at the workplace and this right cannot be compromised, as otherwise this will lead to a suboptimal response to the pandemic. The government, hospital administrators, and health care workers will need to come together and work cohesively.

Ethical issues surrounding resource allocation

At the time of hospital admission, any suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient should have his or her wishes recorded with the admitting team regarding the goals of care and code status. During any critical illness, goals evolve depending on discussions, reflections of the patient with family, and clinical response to therapy. A patient who does not want any kind of life support obviously should not be offered an ICU level of care.

On the other hand, in the event of resources becoming overwhelmed by demand as can be expected during this pandemic, careful ethical considerations will need to be applied.

A carefully crafted transparent ethical framework, with a clear understanding of the decision-making process, that involves all stakeholders – including government entities, public health officials, health care workers, ethics specialists, and members of the community – is essential. Ideally, allocation of resources should be made according to a well-written plan, by a triage team that can include a nontreating physician, bioethicists, legal personnel, and religious representatives. It should not be left to the front-line treating physician, who is unlikely to be trained to make these decisions and who has an ethical responsibility to advocate for the patient under his care.

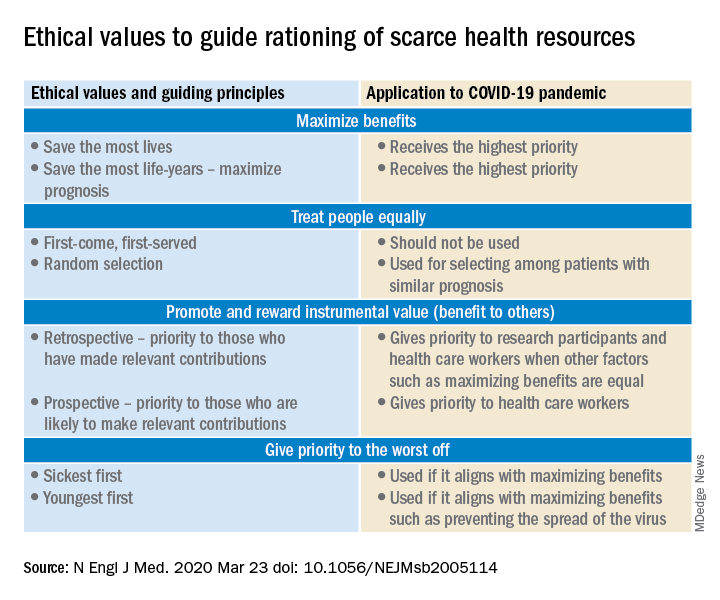

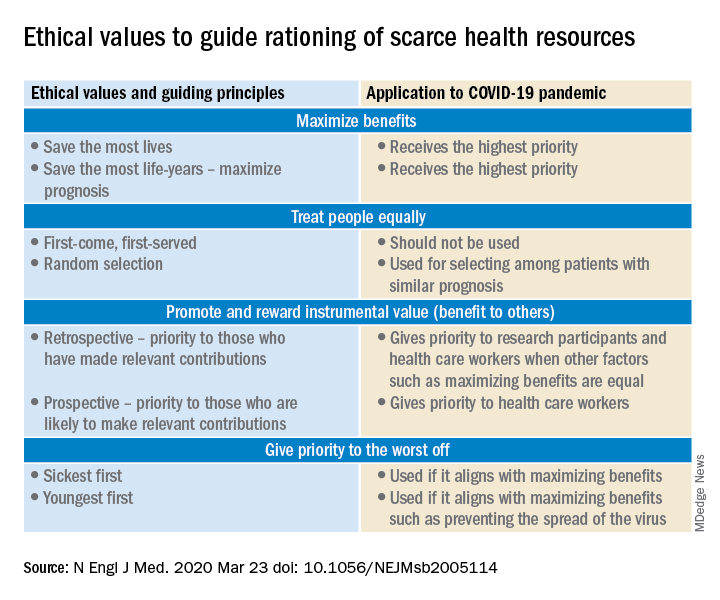

Ethical principles that deserve consideration

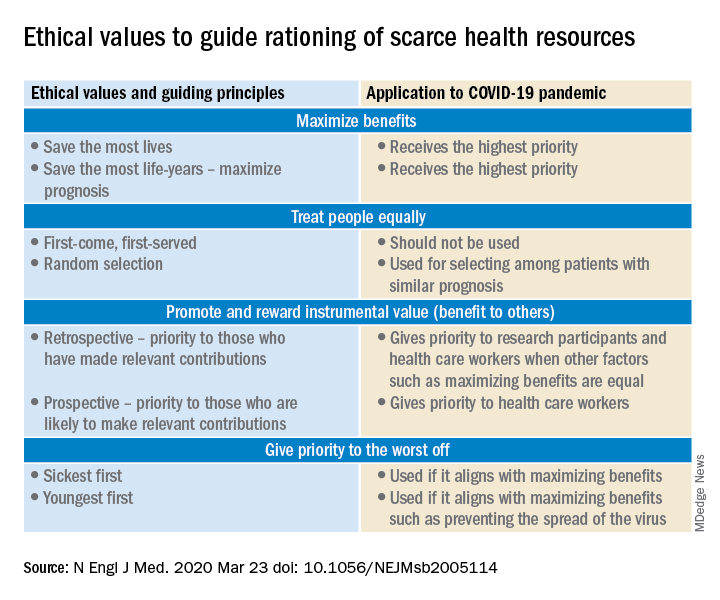

The “principle of utility” provides the maximum possible benefit to the maximum number of people. It should not only save the greatest number of lives but also maximize improvements in individuals’ posttreatment length of life.

The “principle of equity” requires that resources are allocated on a nondiscriminatory basis with a fair distribution of benefits and burdens. When conflicts arise between these two principles, a balanced approach likely will help when handled with a transparent decision-making process, with decisions to be applied consistently. Most experts would agree on not only saving more lives but also in preserving more years of life.

The distribution of medical resources should not be based on age or disability. Frailty and functional status are important considerations; however, priority is to be given to sicker patients who have lesser comorbidities and are also likely to survive longer. This could entail that younger, healthier patients will access scarce resources based on the principle of maximizing benefits.

Another consideration is “preservation of functioning of the society.” Those individuals who are important for providing important public services, health care services, and the functioning of other key aspects of society can be considered for prioritization of resources. While this may not satisfy the classic utilitarian principle of doing maximum good to the maximum number of people, it will help to continue augmenting the fight against the pandemic because of the critical role that such individuals play.

For patients with a similar prognosis, the principle of equality comes into play, and distribution should be done by way of random allocation, like a lottery. Distribution based on the principle of “first come, first served” is unlikely to be a fair process, as it would likely discriminate against patients based on their ability to access care.

Care should also be taken not to discriminate among people who have COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 health conditions that require medical care. Distribution should never be done based on an individual’s political influence, celebrity, or financial status, as occurred in the early days of the pandemic regarding access to testing.

Resuscitation or not?

Should a COVID-19 positive patient be offered CPR in case of cardiac arrest? The concern is that CPR is a high-level aerosolizing procedure and PPE is in short supply with the worsening of the pandemic. This will depend more on local policies and resource availability, along with goals of care that have to be determined at the time of admission and subsequent conversations.

The American Hospital Association has issued a general guideline and as more data become available, we can have more informed discussions with patients and families. At this point, all due precautions that prevent the infection of health care personnel are applicable.

Ethical considerations often do not have answers that are a universal fit, and the challenge is always to promote the best interest of the patient with a balance of judiciously utilizing scarce community resources.

Although many states have had discussions and some even have written policies, they have never been implemented. The organization and application of a judicious ethical “crisis level of care” is extremely challenging and likely to test the foundation and fabric of the society.

Dr. Jain is senior associate consultant, hospital & critical care medicine, at Mayo Clinic in Mankato, Minn. He is a board-certified internal medicine, pulmonary, and critical care physician, and has special interests in rural medicine and ethical issues involving critical care medicine. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of keystone infectious diseases/HIV in Chambersburg and is currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro Hospitals, all in Pennsylvania. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Sources

1. United States Resource Availability for COVID-19. SCCM Blog.

2. Intensive care medicine: Triage in case of bottlenecks. l

3. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Providers during COVID-19 Outbreak.

4. Emanuel EJ et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020 Mar 23.doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114.

5. Devnani M et al. Planning and response to the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: Ethics, equity and justice. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011 Oct-Dec;8(4):237-40.

6. Alexander C and Wynia M. Ready and willing? Physicians’ sense of preparedness for bioterrorism. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):189-97.

7. Damery S et al. Healthcare workers’ perceptions of the duty to work during an influenza pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2010 Jan;36(1):12-8.

COVID-19 has been a watershed event in medical history of epic proportions. With this fast-spreading pandemic stretching resources at health care institutions, practical considerations for management of a disease about which we are still learning has been a huge challenge.

Although many guidelines have been made available by medical societies and experts worldwide, there appear to be very few which throw light on management in a resource-poor setup. The hospitalist, as a front-line provider, is likely expected to lead the planning and management of resources in order to deliver appropriate care.

As per American Hospital Association data, there are 2,704 community hospitals that can deliver ICU care in the United States. There are 534,964 acute care beds with 96,596 ICU beds. Additionally, there are 25,157 step-down beds and 1,183 burn unit beds. Of the 2,704 hospitals, 74% are in metropolitan areas (> 50,000 population), 17% (464) are in micropolitan areas (10,000-49,999 population), and the remaining 9% (244) are in rural areas. Only 7% (36,453) of hospital beds and 5% (4715) of ICU beds are in micropolitan areas. Two percent of acute care hospital beds and 1% of ICU beds are in rural areas. Although the US has the highest per capita number of ICU beds in the world, this may not be sufficient as these are concentrated in highly populated metropolitan areas.

Infrastructure and human power resource augmentation will be important. Infrastructure can be ramped up by:

- Canceling elective procedures

- Using the operating room and perioperative room ventilators and beds

- Servicing and using older functioning hospitals, medical wards, and ventilators.

As ventilators are expected to be in short supply, while far from ideal, other resources may include using ventilators from the Strategic National Stockpile, renting from vendors, and using state-owned stockpiles. Use of non-invasive ventilators, such as CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), BiPAP (bi-level positive airway pressure), and HFNC (high-flow nasal cannula) may be considered in addition to full-featured ventilators. Rapidly manufacturing new ventilators with government direction is also being undertaken.

Although estimates vary based on the model used, about 1 million people are expected to need ventilatory support. However, in addition to infrastructural shortcomings, trained persons to care for these patients are lacking. Approximately 48% of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, and there are only 28,808 intensivists as per 2015 AHA data. In order to increase the amount of skilled manpower needed to staff ICUs, a model from the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Fundamental Disaster Management Program can be adopted. This involves an intensivist overseeing four different teams, with each team caring for 24 patients. Each team is led by a non-ICU physician or an ICU advanced practice provider (APP) who in turn cares for the patient with respiratory therapists, pharmacists, ICU nurses, and other non-ICU health professionals.

It is essential that infrastructure and human power be augmented and optimized, as well as contingency plans, including triage based on ethical and legal considerations, put in place if demand overwhelms capacity.

Lack of PPE and fear among health care staff

There have been widespread reports in the media, and several anecdotal reports, about severe shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), and as a result, an increase in fear and anxiety among frontline health care workers.

In addition, there also have been reports about hospital administrators disciplining medical and nursing staff for voicing their concerns about PPE shortages to the general public and the media. This likely stems from the narrow “optics” and public relations concerns of health care facilities.

It is evident that the size and magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic was grossly underestimated, and preparations were inadequate. But according to past surveys of health care workers, a good number of them believe that medical and nursing staff have a duty to deliver care to sick people even if it exposes them to personal danger.

Given the special skills and privileges that health care professionals possess, they do have a moral and ethical responsibility to take care of sick patients even if a danger to themselves exists. However, society also has a responsibility to provide for the safety of these health care workers by supplying them with appropriate safety gear. Given the unprecedented nature of this pandemic, it is obvious that federal and state governments, public health officials, and hospital administrators (along with health care professionals) are still learning how to appropriately respond to the challenge.

It would be reasonable and appropriate for everyone concerned to understand and acknowledge that there is a shortage of PPE, and while arranging for this to be replenished, undertake and implement measures that maximize the safety of all health care workers. An open forum, mutually agreed-upon policy and procedures, along with mechanisms to address concerns should be formulated.

In addition, health care workers who test positive for COVID-19 can be a source of infection for other health care workers and non-infected patients. Therefore, health care workers have the responsibility of reporting their symptoms, the right to have themselves tested, and they must follow agreed-upon procedures that would limit their ability to infect other people, including mandated absenteeism from work. Every individual has a right to safety at the workplace and this right cannot be compromised, as otherwise this will lead to a suboptimal response to the pandemic. The government, hospital administrators, and health care workers will need to come together and work cohesively.

Ethical issues surrounding resource allocation

At the time of hospital admission, any suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient should have his or her wishes recorded with the admitting team regarding the goals of care and code status. During any critical illness, goals evolve depending on discussions, reflections of the patient with family, and clinical response to therapy. A patient who does not want any kind of life support obviously should not be offered an ICU level of care.

On the other hand, in the event of resources becoming overwhelmed by demand as can be expected during this pandemic, careful ethical considerations will need to be applied.

A carefully crafted transparent ethical framework, with a clear understanding of the decision-making process, that involves all stakeholders – including government entities, public health officials, health care workers, ethics specialists, and members of the community – is essential. Ideally, allocation of resources should be made according to a well-written plan, by a triage team that can include a nontreating physician, bioethicists, legal personnel, and religious representatives. It should not be left to the front-line treating physician, who is unlikely to be trained to make these decisions and who has an ethical responsibility to advocate for the patient under his care.

Ethical principles that deserve consideration

The “principle of utility” provides the maximum possible benefit to the maximum number of people. It should not only save the greatest number of lives but also maximize improvements in individuals’ posttreatment length of life.

The “principle of equity” requires that resources are allocated on a nondiscriminatory basis with a fair distribution of benefits and burdens. When conflicts arise between these two principles, a balanced approach likely will help when handled with a transparent decision-making process, with decisions to be applied consistently. Most experts would agree on not only saving more lives but also in preserving more years of life.

The distribution of medical resources should not be based on age or disability. Frailty and functional status are important considerations; however, priority is to be given to sicker patients who have lesser comorbidities and are also likely to survive longer. This could entail that younger, healthier patients will access scarce resources based on the principle of maximizing benefits.

Another consideration is “preservation of functioning of the society.” Those individuals who are important for providing important public services, health care services, and the functioning of other key aspects of society can be considered for prioritization of resources. While this may not satisfy the classic utilitarian principle of doing maximum good to the maximum number of people, it will help to continue augmenting the fight against the pandemic because of the critical role that such individuals play.

For patients with a similar prognosis, the principle of equality comes into play, and distribution should be done by way of random allocation, like a lottery. Distribution based on the principle of “first come, first served” is unlikely to be a fair process, as it would likely discriminate against patients based on their ability to access care.

Care should also be taken not to discriminate among people who have COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 health conditions that require medical care. Distribution should never be done based on an individual’s political influence, celebrity, or financial status, as occurred in the early days of the pandemic regarding access to testing.

Resuscitation or not?

Should a COVID-19 positive patient be offered CPR in case of cardiac arrest? The concern is that CPR is a high-level aerosolizing procedure and PPE is in short supply with the worsening of the pandemic. This will depend more on local policies and resource availability, along with goals of care that have to be determined at the time of admission and subsequent conversations.

The American Hospital Association has issued a general guideline and as more data become available, we can have more informed discussions with patients and families. At this point, all due precautions that prevent the infection of health care personnel are applicable.

Ethical considerations often do not have answers that are a universal fit, and the challenge is always to promote the best interest of the patient with a balance of judiciously utilizing scarce community resources.

Although many states have had discussions and some even have written policies, they have never been implemented. The organization and application of a judicious ethical “crisis level of care” is extremely challenging and likely to test the foundation and fabric of the society.

Dr. Jain is senior associate consultant, hospital & critical care medicine, at Mayo Clinic in Mankato, Minn. He is a board-certified internal medicine, pulmonary, and critical care physician, and has special interests in rural medicine and ethical issues involving critical care medicine. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of keystone infectious diseases/HIV in Chambersburg and is currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro Hospitals, all in Pennsylvania. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Sources

1. United States Resource Availability for COVID-19. SCCM Blog.

2. Intensive care medicine: Triage in case of bottlenecks. l

3. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Providers during COVID-19 Outbreak.

4. Emanuel EJ et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020 Mar 23.doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114.

5. Devnani M et al. Planning and response to the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: Ethics, equity and justice. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011 Oct-Dec;8(4):237-40.

6. Alexander C and Wynia M. Ready and willing? Physicians’ sense of preparedness for bioterrorism. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):189-97.

7. Damery S et al. Healthcare workers’ perceptions of the duty to work during an influenza pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2010 Jan;36(1):12-8.

COVID-19 has been a watershed event in medical history of epic proportions. With this fast-spreading pandemic stretching resources at health care institutions, practical considerations for management of a disease about which we are still learning has been a huge challenge.

Although many guidelines have been made available by medical societies and experts worldwide, there appear to be very few which throw light on management in a resource-poor setup. The hospitalist, as a front-line provider, is likely expected to lead the planning and management of resources in order to deliver appropriate care.

As per American Hospital Association data, there are 2,704 community hospitals that can deliver ICU care in the United States. There are 534,964 acute care beds with 96,596 ICU beds. Additionally, there are 25,157 step-down beds and 1,183 burn unit beds. Of the 2,704 hospitals, 74% are in metropolitan areas (> 50,000 population), 17% (464) are in micropolitan areas (10,000-49,999 population), and the remaining 9% (244) are in rural areas. Only 7% (36,453) of hospital beds and 5% (4715) of ICU beds are in micropolitan areas. Two percent of acute care hospital beds and 1% of ICU beds are in rural areas. Although the US has the highest per capita number of ICU beds in the world, this may not be sufficient as these are concentrated in highly populated metropolitan areas.

Infrastructure and human power resource augmentation will be important. Infrastructure can be ramped up by:

- Canceling elective procedures

- Using the operating room and perioperative room ventilators and beds

- Servicing and using older functioning hospitals, medical wards, and ventilators.

As ventilators are expected to be in short supply, while far from ideal, other resources may include using ventilators from the Strategic National Stockpile, renting from vendors, and using state-owned stockpiles. Use of non-invasive ventilators, such as CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), BiPAP (bi-level positive airway pressure), and HFNC (high-flow nasal cannula) may be considered in addition to full-featured ventilators. Rapidly manufacturing new ventilators with government direction is also being undertaken.

Although estimates vary based on the model used, about 1 million people are expected to need ventilatory support. However, in addition to infrastructural shortcomings, trained persons to care for these patients are lacking. Approximately 48% of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, and there are only 28,808 intensivists as per 2015 AHA data. In order to increase the amount of skilled manpower needed to staff ICUs, a model from the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Fundamental Disaster Management Program can be adopted. This involves an intensivist overseeing four different teams, with each team caring for 24 patients. Each team is led by a non-ICU physician or an ICU advanced practice provider (APP) who in turn cares for the patient with respiratory therapists, pharmacists, ICU nurses, and other non-ICU health professionals.

It is essential that infrastructure and human power be augmented and optimized, as well as contingency plans, including triage based on ethical and legal considerations, put in place if demand overwhelms capacity.

Lack of PPE and fear among health care staff

There have been widespread reports in the media, and several anecdotal reports, about severe shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), and as a result, an increase in fear and anxiety among frontline health care workers.

In addition, there also have been reports about hospital administrators disciplining medical and nursing staff for voicing their concerns about PPE shortages to the general public and the media. This likely stems from the narrow “optics” and public relations concerns of health care facilities.

It is evident that the size and magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic was grossly underestimated, and preparations were inadequate. But according to past surveys of health care workers, a good number of them believe that medical and nursing staff have a duty to deliver care to sick people even if it exposes them to personal danger.

Given the special skills and privileges that health care professionals possess, they do have a moral and ethical responsibility to take care of sick patients even if a danger to themselves exists. However, society also has a responsibility to provide for the safety of these health care workers by supplying them with appropriate safety gear. Given the unprecedented nature of this pandemic, it is obvious that federal and state governments, public health officials, and hospital administrators (along with health care professionals) are still learning how to appropriately respond to the challenge.

It would be reasonable and appropriate for everyone concerned to understand and acknowledge that there is a shortage of PPE, and while arranging for this to be replenished, undertake and implement measures that maximize the safety of all health care workers. An open forum, mutually agreed-upon policy and procedures, along with mechanisms to address concerns should be formulated.

In addition, health care workers who test positive for COVID-19 can be a source of infection for other health care workers and non-infected patients. Therefore, health care workers have the responsibility of reporting their symptoms, the right to have themselves tested, and they must follow agreed-upon procedures that would limit their ability to infect other people, including mandated absenteeism from work. Every individual has a right to safety at the workplace and this right cannot be compromised, as otherwise this will lead to a suboptimal response to the pandemic. The government, hospital administrators, and health care workers will need to come together and work cohesively.

Ethical issues surrounding resource allocation

At the time of hospital admission, any suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient should have his or her wishes recorded with the admitting team regarding the goals of care and code status. During any critical illness, goals evolve depending on discussions, reflections of the patient with family, and clinical response to therapy. A patient who does not want any kind of life support obviously should not be offered an ICU level of care.

On the other hand, in the event of resources becoming overwhelmed by demand as can be expected during this pandemic, careful ethical considerations will need to be applied.

A carefully crafted transparent ethical framework, with a clear understanding of the decision-making process, that involves all stakeholders – including government entities, public health officials, health care workers, ethics specialists, and members of the community – is essential. Ideally, allocation of resources should be made according to a well-written plan, by a triage team that can include a nontreating physician, bioethicists, legal personnel, and religious representatives. It should not be left to the front-line treating physician, who is unlikely to be trained to make these decisions and who has an ethical responsibility to advocate for the patient under his care.

Ethical principles that deserve consideration

The “principle of utility” provides the maximum possible benefit to the maximum number of people. It should not only save the greatest number of lives but also maximize improvements in individuals’ posttreatment length of life.

The “principle of equity” requires that resources are allocated on a nondiscriminatory basis with a fair distribution of benefits and burdens. When conflicts arise between these two principles, a balanced approach likely will help when handled with a transparent decision-making process, with decisions to be applied consistently. Most experts would agree on not only saving more lives but also in preserving more years of life.

The distribution of medical resources should not be based on age or disability. Frailty and functional status are important considerations; however, priority is to be given to sicker patients who have lesser comorbidities and are also likely to survive longer. This could entail that younger, healthier patients will access scarce resources based on the principle of maximizing benefits.

Another consideration is “preservation of functioning of the society.” Those individuals who are important for providing important public services, health care services, and the functioning of other key aspects of society can be considered for prioritization of resources. While this may not satisfy the classic utilitarian principle of doing maximum good to the maximum number of people, it will help to continue augmenting the fight against the pandemic because of the critical role that such individuals play.

For patients with a similar prognosis, the principle of equality comes into play, and distribution should be done by way of random allocation, like a lottery. Distribution based on the principle of “first come, first served” is unlikely to be a fair process, as it would likely discriminate against patients based on their ability to access care.

Care should also be taken not to discriminate among people who have COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 health conditions that require medical care. Distribution should never be done based on an individual’s political influence, celebrity, or financial status, as occurred in the early days of the pandemic regarding access to testing.

Resuscitation or not?

Should a COVID-19 positive patient be offered CPR in case of cardiac arrest? The concern is that CPR is a high-level aerosolizing procedure and PPE is in short supply with the worsening of the pandemic. This will depend more on local policies and resource availability, along with goals of care that have to be determined at the time of admission and subsequent conversations.

The American Hospital Association has issued a general guideline and as more data become available, we can have more informed discussions with patients and families. At this point, all due precautions that prevent the infection of health care personnel are applicable.

Ethical considerations often do not have answers that are a universal fit, and the challenge is always to promote the best interest of the patient with a balance of judiciously utilizing scarce community resources.

Although many states have had discussions and some even have written policies, they have never been implemented. The organization and application of a judicious ethical “crisis level of care” is extremely challenging and likely to test the foundation and fabric of the society.

Dr. Jain is senior associate consultant, hospital & critical care medicine, at Mayo Clinic in Mankato, Minn. He is a board-certified internal medicine, pulmonary, and critical care physician, and has special interests in rural medicine and ethical issues involving critical care medicine. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of keystone infectious diseases/HIV in Chambersburg and is currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro Hospitals, all in Pennsylvania. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Sources

1. United States Resource Availability for COVID-19. SCCM Blog.

2. Intensive care medicine: Triage in case of bottlenecks. l

3. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Providers during COVID-19 Outbreak.

4. Emanuel EJ et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020 Mar 23.doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114.

5. Devnani M et al. Planning and response to the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: Ethics, equity and justice. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011 Oct-Dec;8(4):237-40.

6. Alexander C and Wynia M. Ready and willing? Physicians’ sense of preparedness for bioterrorism. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):189-97.

7. Damery S et al. Healthcare workers’ perceptions of the duty to work during an influenza pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2010 Jan;36(1):12-8.