User login

Rare Cutaneous Presentation of Burkitt Lymphoma

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with progressive abdominal and hip pain of several weeks’ duration that was accompanied by unilateral swelling of the left leg. He had a medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and prediabetes. Computed tomography (CT) showed extensive intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, and pelvic lymphadenopathy in addition to poorly defined hepatic lesions.

A CT-guided core biopsy of a left inguinal lymph node showed Burkitt lymphoma. Fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for oncogene c-MYC rearrangement on chromosome 8q24 and negative for B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) and B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6) gene rearrangements. Flow cytometry demonstrated an aberrant population of κ light chain-restricted CD5−CD10+ B lymphocytes.

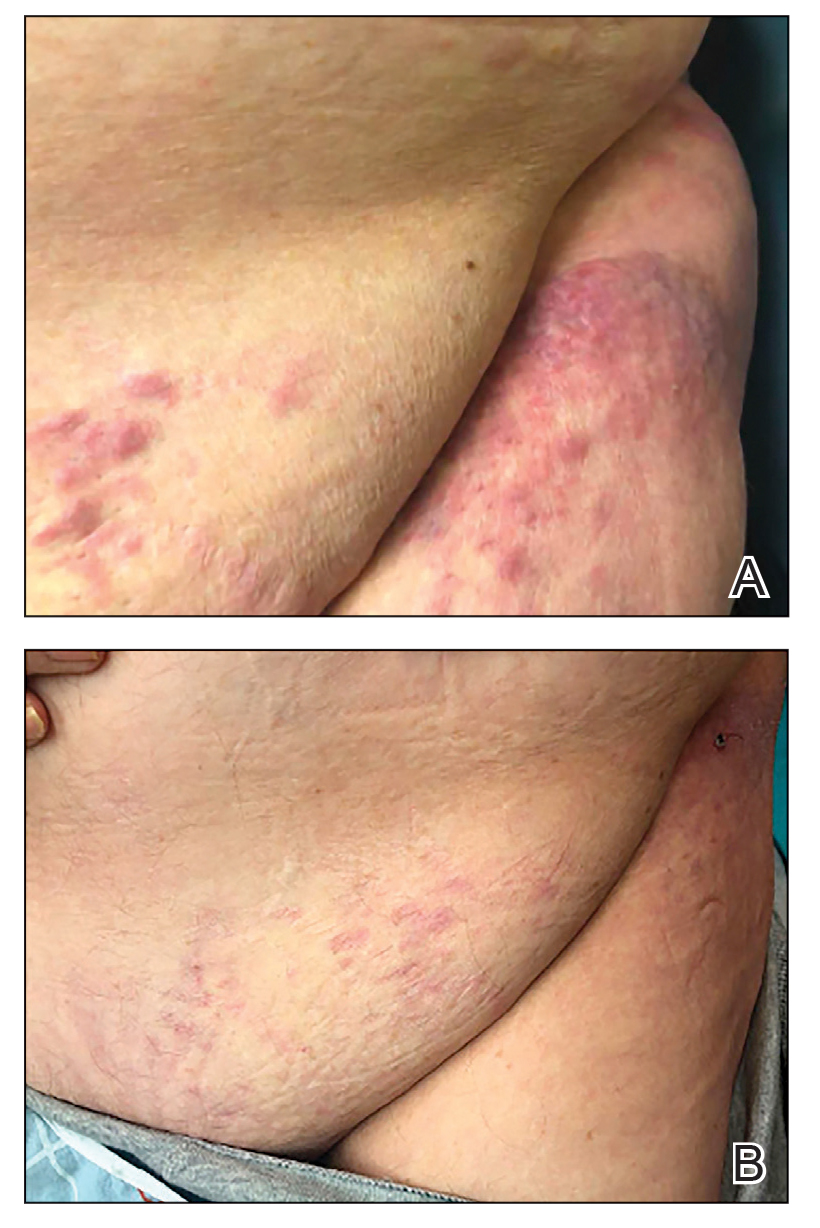

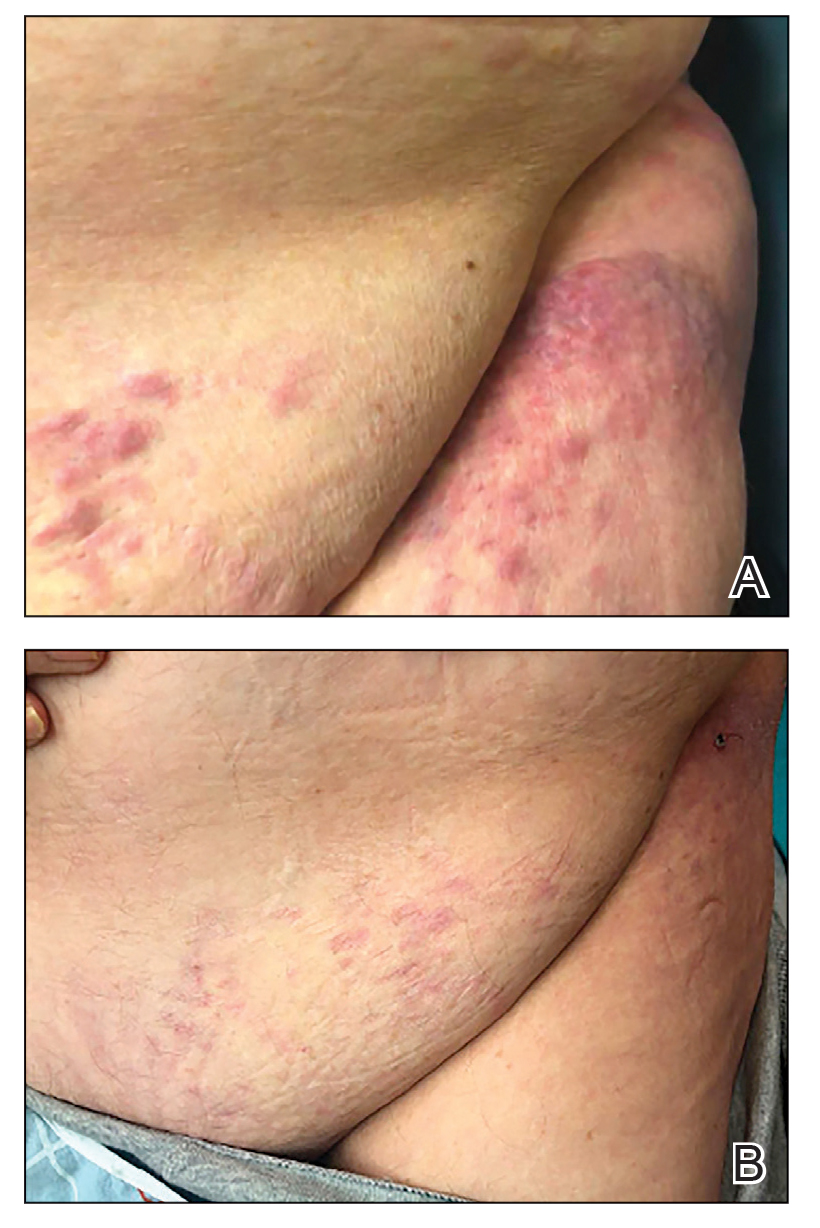

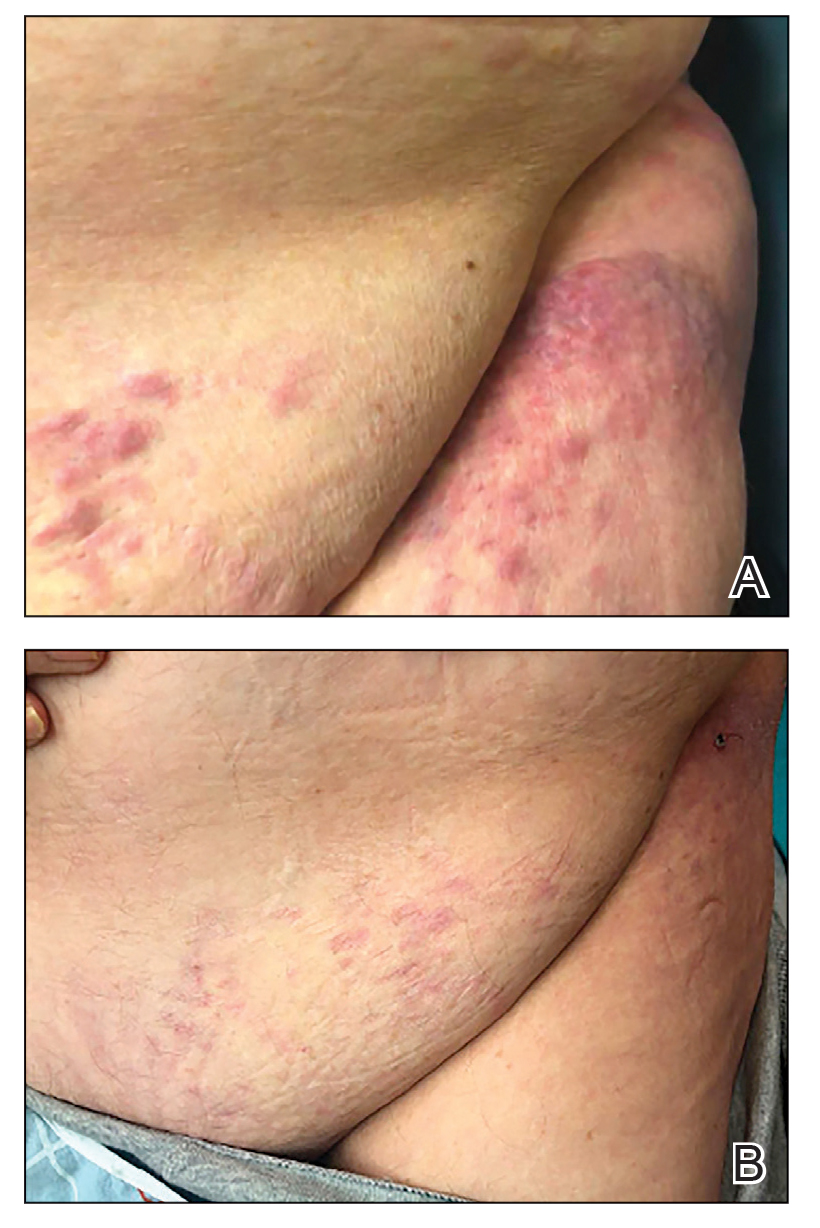

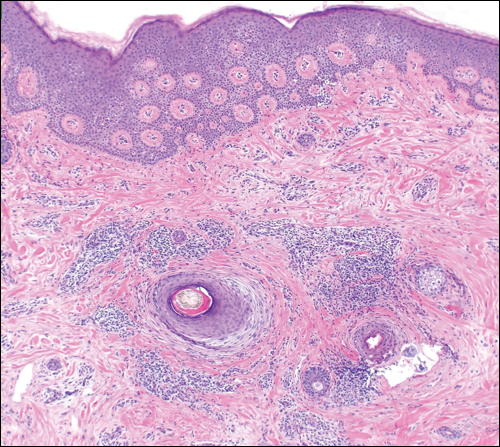

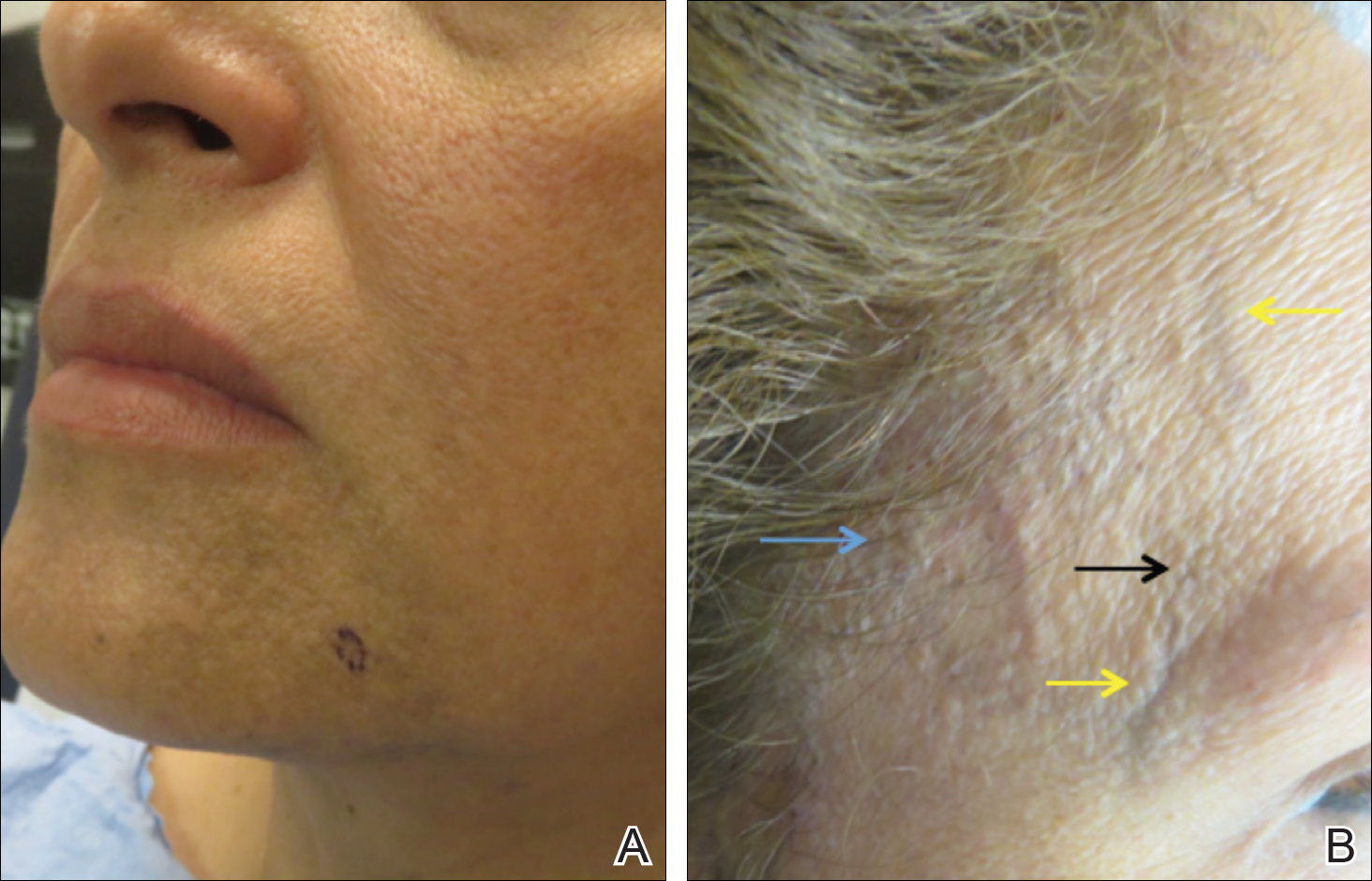

The patient’s overall disease burden was consistent with stage IV Burkitt lymphoma. R-miniCHOP chemotherapy—rituximab plus a reduced dose of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone—was initiated. Approximately 2 weeks after chemotherapy was initiated, the patient developed a firm erythematous eruption on the left hip (Figure 1A). His regimen was then switched to R-EPOCH—rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin—at the time of discharge, and he was referred to dermatology due to an initial concern of an adverse reaction to R-EPOCH chemotherapy. The patient denied any pain, pruritus, or irritation. Physical examination showed multifocal, subcutaneous, indurated, erythematous and violaceous nodules without epidermal changes. Some nodules on the lateral aspect of the hip coalesced to form firm plaques.

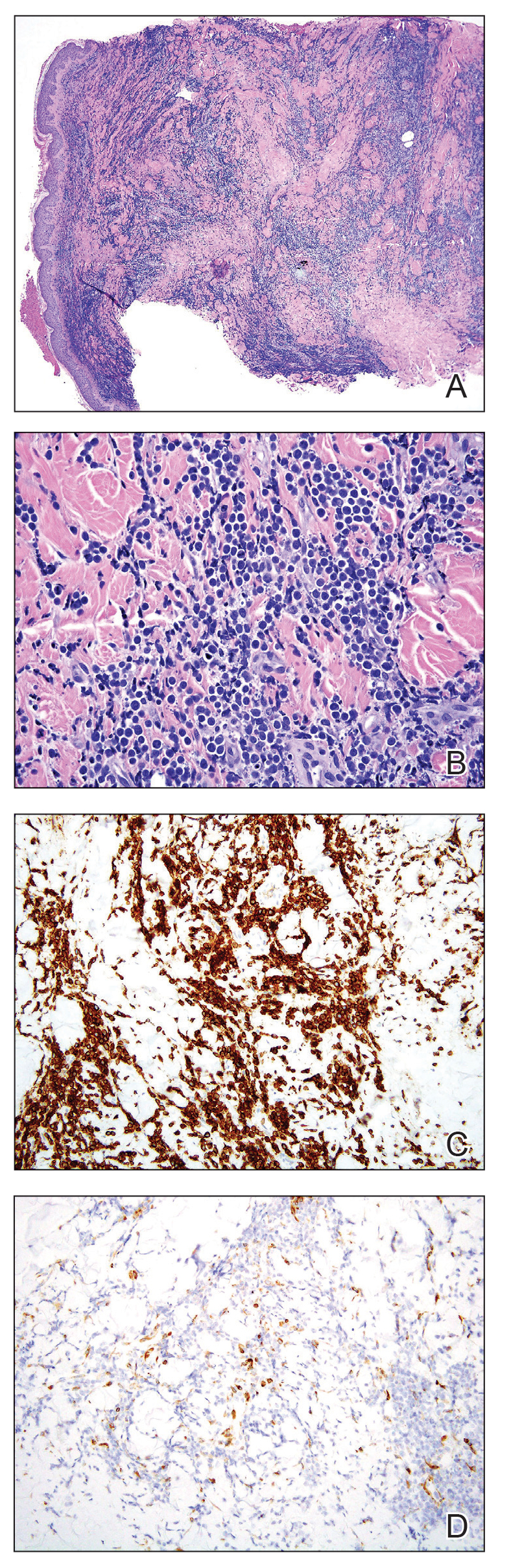

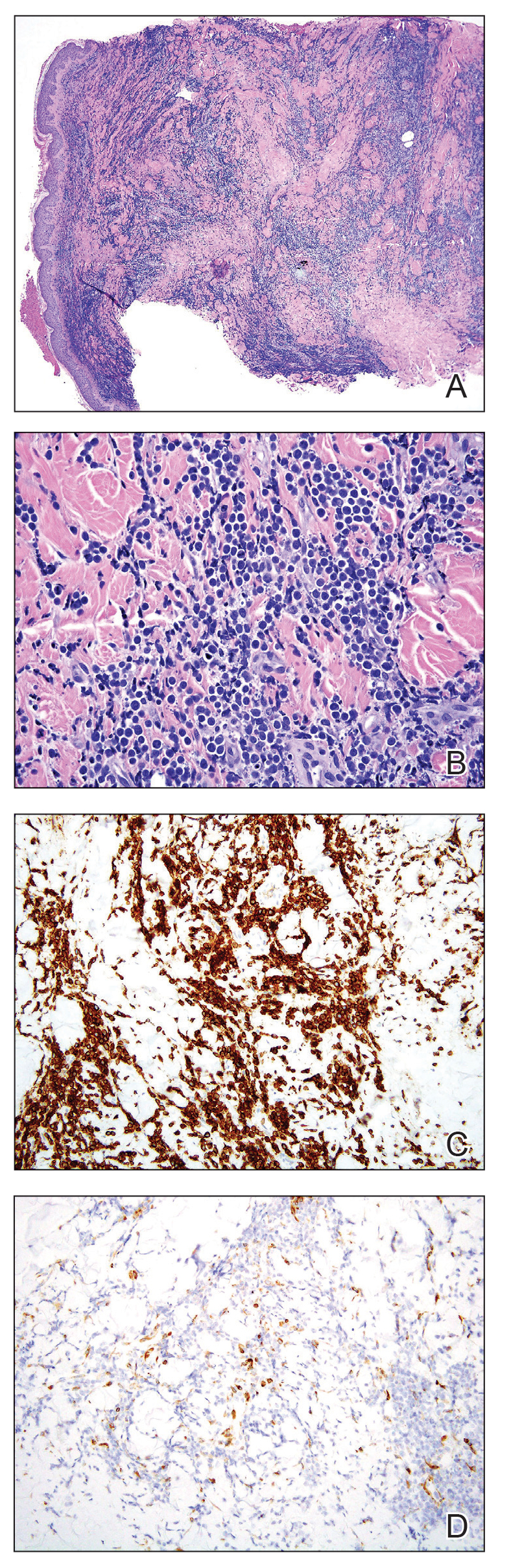

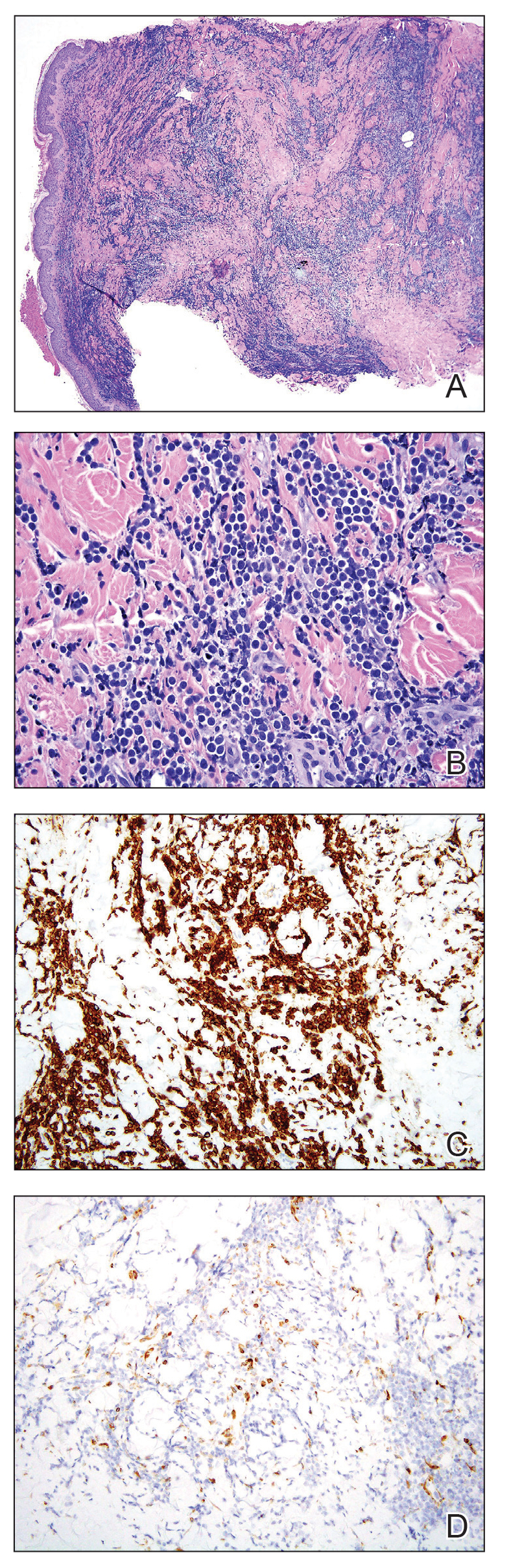

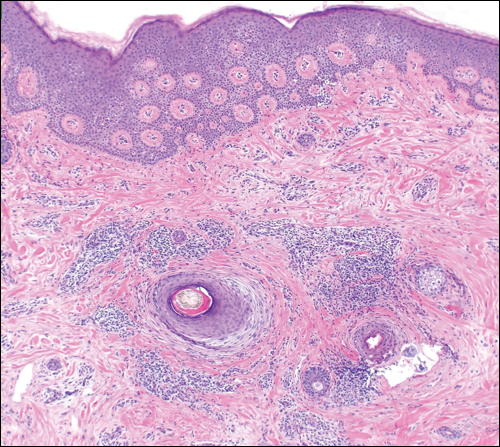

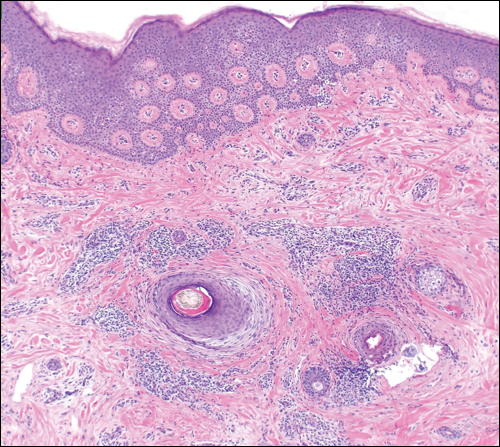

A punch biopsy specimen showed markedly atypical lymphocytes with enlarged nuclei and scant cytoplasm present throughout the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). Numerous apoptotic cells and cellular debris were seen. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that the lymphocytic infiltrate comprised CD79a+ B cells that were positive for Bcl-6 and CD10 and negative for Bcl-2 (Figures 2C and 2D). There also was diminished focal expression of CD20. Ki-67 protein staining was intensely positive and demonstrated a very high proliferative index.

Taken together, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of Burkitt lymphoma. The patient’s cutaneous lesions improved after continued aggressive chemotherapy. At follow-up 2 weeks after biopsy, he was receiving his second round of R-EPOCH chemotherapy with appreciable regression of skin lesions (Figure 1B). However, he then developed right-side double vision, ptosis, and right-side facial paresthesia. Although magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and lumbar puncture did not show evidence of central nervous system involvement, the chemotherapy regimen was switched to dose-adjusted CVAD-R—hypercyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin hydrochloride, and dexamethasone plus rituximab—for empiric treatment of central nervous system disease. Although treatment was complicated by sepsis with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacter cloacae, Burkitt lymphoma was found to be in remission after 3 cycles of CVAD-R and 5 months of chemotherapy.

Burkitt lymphoma is a B-cell non-Hodgkin malignancy caused by translocation of chromosome 8 and chromosome 14, leading to overexpression of c-MYC and subsequent hyperproliferation of B lymphocytes.1,2 The disease is divided into 3 major categories: sporadic, endemic, and immunodeficiency related.3 The endemic variant is the most prevalent subtype in Africa and is associated with Plasmodium falciparum malaria; the sporadic variant is the most common subtype in the rest of the world.4

Burkitt lymphoma is highly aggressive and is characterized by unusually high rates of mitosis and apoptosis that result in abundant cellular debris and a distinctive starry-sky pattern on histopathology.5,6 Extranodal metastasis is common,7 but cutaneous involvement is exceedingly rare, with only a few cases having been reported.8-14 Cutaneous metastasis of Burkitt lymphoma often is associated with a high overall disease burden and poor prognosis.8,11

Immunodeficiency-related Burkitt lymphoma is particularly aggressive. Notably, 3 of 7 (42.9%) reported cases of cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma occurred in HIV-positive patients.11,13 In one case, cutaneous involvement was the first sign of relapsed disease that had been in remission.12

Although c-MYC rearrangement is required to make a diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma, the disease also is present in a minority of cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)(6%).15 Although DLBCL typically can be differentiated from Burkitt lymphoma by the large nuclear size and characteristic vesicular nuclei of B cells, few cases of DLBCL with c-MYC rearrangement histologically mimic Burkitt lymphoma. However, key features such as immunohistochemical staining for Bcl-2 and CD10 can be used to distinguish these 2 entities.16 Bcl-2 negativity and CD10 positivity, as seen in our patient, is considered more characteristic of Burkitt lymphoma. This staining pattern in combination with a high Ki-67 fraction (>95%) and the presence of monomorphic medium-sized cells is more consistent with a diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma than of DLBCL.17

Earlier case reports have documented that cutaneous lesions of Burkitt lymphoma can occur in a variety of ways. Hematogenous spread is the likely route of metastasis for lesions distant to the primary site or those that have widespread distribution.18 Alternatively, other reports have suggested that cutaneous metastases can occur from local invasion and subcutaneous extension of malignant cells after a surgical procedure.10,19 For example, cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma has been reported in the setting of celioscopy, occurring directly at the surgical site.19 In our patient, we believe that the route of metastatic spread likely was through subcutaneous invasion secondary to CT-guided core biopsy, which was supported by the observation that the onset of cutaneous manifestations was temporally related to the procedure and that the lesions occurred on the skin directly overlying the biopsy site.

In conclusion, we describe an exceedingly rare presentation of cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma in which a surgical procedure likely served as an inciting event that triggered seeding of malignant cells to the skin. Cutaneous spread of Burkitt lymphoma is infrequently reported; all such reports that provide long-term follow-up data have described it in association with high disease burden and often a lethal outcome.8,11,12 Our patient had complete resolution of cutaneous lesions with chemotherapy. It is unclear if the presence of cutaneous lesions can serve as a prognostic indicator and requires further investigation. However, our case provides preliminary evidence to suggest that cutaneous metastases do not always represent aggressive disease and that cutaneous lesions may respond well to chemotherapy.

- Kalisz K, Alessandrino F, Beck R, et al. An update on Burkitt lymphoma: a review of pathogenesis and multimodality imaging assessment of disease presentation, treatment response, and recurrence. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:56. doi:10.1186/s13244-019-0733-7

- Dunleavy K, Gross TG. Management of aggressive B-cell NHLs in the AYA population: an adult vs pediatric perspective. Blood. 2018;132:369-375. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-02-778480

- Noy A. Burkitt lymphoma—subtypes, pathogenesis, and treatment strategies. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(Suppl 1):S37-S38. doi:10.1016/S2152-2650(20)30455-9

- Lenze D, Leoncini L, Hummel M, et al. The different epidemiologic subtypes of Burkitt lymphoma share a homogenous micro RNA profile distinct from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2011;25:1869-1876. doi:10.1038/leu.2011.156

- Bellan C, Lazzi S, De Falco G, et al. Burkitt’s lymphoma: new insights into molecular pathogenesis. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:188-192. doi:10.1136/jcp.56.3.188

- Chuang S-S, Ye H, Du M-Q, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry in distinguishing Burkitt lymphoma from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with very high proliferation index and with or without a starry-sky pattern: a comparative study with EBER and FISH. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:558-564. doi:10.1309/EQJR3D3V0CCQGP04

- Baker PS, Gold KG, Lane KA, et al. Orbital burkitt lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: a report of 3 cases and a review of the literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:464-468. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b80fde

- Fuhrmann TL, Ignatovich YV, Pentland A. Cutaneous metastatic disease: Burkitt lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1196-1197. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.033

- Burns CA, Scott GA, Miller CC. Leukemia cutis at the site of trauma in a patient with Burkitt leukemia. Cutis. 2005;75:54-56.

- Jacobson MA, Hutcheson ACS, Hurray DH, et al. Cutaneous involvement by Burkitt lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1111-1113. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.02.030

- Berk DR, Cheng A, Lind AC, et al. Burkitt lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Bachmeyer C, Bazarbachi A, Rio B, et al. Specific cutaneous involvement indicating relapse of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 1997;54:176. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199702)54:2<176::aid-ajh20>3.0.co;2-c

- Rogers A, Graves M, Toscano M, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of Burkitt lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:997-1001. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000004

- Thakkar D, Lipi L, Misra R, et al. Skin involvement in Burkitt’s lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2018;11:251-252. doi:10.1016/j.hemonc.2018.01.002

- Akasaka T, Akasaka H, Ueda C, et al. Molecular and clinical features of non-Burkitt’s, diffuse large-cell lymphoma of B-cell type associated with the c-MYC/immunoglobulin heavy-chain fusion gene. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:510-518. doi:10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.510

- Nakamura N, Nakamine H, Tamaru J-I, et al. The distinction between Burkitt lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with c-myc rearrangement. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:771-776. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000019577.73786.64

- Bellan C, Stefano L, Giulia de F, et al. Burkitt lymphoma versus diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a practical approach. Hematol Oncol. 2010;28:53-56. doi:10.1002/hon.916

- Amonchaisakda N, Aiempanakit K, Apinantriyo B. Burkitt lymphoma initially mimicking varicella zoster infection. IDCases. 2020;21:E00818. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00818

- Aractingi S, Marolleau JP, Daniel MT, et al. Subcutaneous localizations of Burkitt lymphoma after celioscopy. Am J Hematol. 1993;42:408. doi:10.1002/ajh.2830420421

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with progressive abdominal and hip pain of several weeks’ duration that was accompanied by unilateral swelling of the left leg. He had a medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and prediabetes. Computed tomography (CT) showed extensive intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, and pelvic lymphadenopathy in addition to poorly defined hepatic lesions.

A CT-guided core biopsy of a left inguinal lymph node showed Burkitt lymphoma. Fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for oncogene c-MYC rearrangement on chromosome 8q24 and negative for B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) and B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6) gene rearrangements. Flow cytometry demonstrated an aberrant population of κ light chain-restricted CD5−CD10+ B lymphocytes.

The patient’s overall disease burden was consistent with stage IV Burkitt lymphoma. R-miniCHOP chemotherapy—rituximab plus a reduced dose of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone—was initiated. Approximately 2 weeks after chemotherapy was initiated, the patient developed a firm erythematous eruption on the left hip (Figure 1A). His regimen was then switched to R-EPOCH—rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin—at the time of discharge, and he was referred to dermatology due to an initial concern of an adverse reaction to R-EPOCH chemotherapy. The patient denied any pain, pruritus, or irritation. Physical examination showed multifocal, subcutaneous, indurated, erythematous and violaceous nodules without epidermal changes. Some nodules on the lateral aspect of the hip coalesced to form firm plaques.

A punch biopsy specimen showed markedly atypical lymphocytes with enlarged nuclei and scant cytoplasm present throughout the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). Numerous apoptotic cells and cellular debris were seen. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that the lymphocytic infiltrate comprised CD79a+ B cells that were positive for Bcl-6 and CD10 and negative for Bcl-2 (Figures 2C and 2D). There also was diminished focal expression of CD20. Ki-67 protein staining was intensely positive and demonstrated a very high proliferative index.

Taken together, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of Burkitt lymphoma. The patient’s cutaneous lesions improved after continued aggressive chemotherapy. At follow-up 2 weeks after biopsy, he was receiving his second round of R-EPOCH chemotherapy with appreciable regression of skin lesions (Figure 1B). However, he then developed right-side double vision, ptosis, and right-side facial paresthesia. Although magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and lumbar puncture did not show evidence of central nervous system involvement, the chemotherapy regimen was switched to dose-adjusted CVAD-R—hypercyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin hydrochloride, and dexamethasone plus rituximab—for empiric treatment of central nervous system disease. Although treatment was complicated by sepsis with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacter cloacae, Burkitt lymphoma was found to be in remission after 3 cycles of CVAD-R and 5 months of chemotherapy.

Burkitt lymphoma is a B-cell non-Hodgkin malignancy caused by translocation of chromosome 8 and chromosome 14, leading to overexpression of c-MYC and subsequent hyperproliferation of B lymphocytes.1,2 The disease is divided into 3 major categories: sporadic, endemic, and immunodeficiency related.3 The endemic variant is the most prevalent subtype in Africa and is associated with Plasmodium falciparum malaria; the sporadic variant is the most common subtype in the rest of the world.4

Burkitt lymphoma is highly aggressive and is characterized by unusually high rates of mitosis and apoptosis that result in abundant cellular debris and a distinctive starry-sky pattern on histopathology.5,6 Extranodal metastasis is common,7 but cutaneous involvement is exceedingly rare, with only a few cases having been reported.8-14 Cutaneous metastasis of Burkitt lymphoma often is associated with a high overall disease burden and poor prognosis.8,11

Immunodeficiency-related Burkitt lymphoma is particularly aggressive. Notably, 3 of 7 (42.9%) reported cases of cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma occurred in HIV-positive patients.11,13 In one case, cutaneous involvement was the first sign of relapsed disease that had been in remission.12

Although c-MYC rearrangement is required to make a diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma, the disease also is present in a minority of cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)(6%).15 Although DLBCL typically can be differentiated from Burkitt lymphoma by the large nuclear size and characteristic vesicular nuclei of B cells, few cases of DLBCL with c-MYC rearrangement histologically mimic Burkitt lymphoma. However, key features such as immunohistochemical staining for Bcl-2 and CD10 can be used to distinguish these 2 entities.16 Bcl-2 negativity and CD10 positivity, as seen in our patient, is considered more characteristic of Burkitt lymphoma. This staining pattern in combination with a high Ki-67 fraction (>95%) and the presence of monomorphic medium-sized cells is more consistent with a diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma than of DLBCL.17

Earlier case reports have documented that cutaneous lesions of Burkitt lymphoma can occur in a variety of ways. Hematogenous spread is the likely route of metastasis for lesions distant to the primary site or those that have widespread distribution.18 Alternatively, other reports have suggested that cutaneous metastases can occur from local invasion and subcutaneous extension of malignant cells after a surgical procedure.10,19 For example, cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma has been reported in the setting of celioscopy, occurring directly at the surgical site.19 In our patient, we believe that the route of metastatic spread likely was through subcutaneous invasion secondary to CT-guided core biopsy, which was supported by the observation that the onset of cutaneous manifestations was temporally related to the procedure and that the lesions occurred on the skin directly overlying the biopsy site.

In conclusion, we describe an exceedingly rare presentation of cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma in which a surgical procedure likely served as an inciting event that triggered seeding of malignant cells to the skin. Cutaneous spread of Burkitt lymphoma is infrequently reported; all such reports that provide long-term follow-up data have described it in association with high disease burden and often a lethal outcome.8,11,12 Our patient had complete resolution of cutaneous lesions with chemotherapy. It is unclear if the presence of cutaneous lesions can serve as a prognostic indicator and requires further investigation. However, our case provides preliminary evidence to suggest that cutaneous metastases do not always represent aggressive disease and that cutaneous lesions may respond well to chemotherapy.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with progressive abdominal and hip pain of several weeks’ duration that was accompanied by unilateral swelling of the left leg. He had a medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and prediabetes. Computed tomography (CT) showed extensive intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, and pelvic lymphadenopathy in addition to poorly defined hepatic lesions.

A CT-guided core biopsy of a left inguinal lymph node showed Burkitt lymphoma. Fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for oncogene c-MYC rearrangement on chromosome 8q24 and negative for B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) and B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6) gene rearrangements. Flow cytometry demonstrated an aberrant population of κ light chain-restricted CD5−CD10+ B lymphocytes.

The patient’s overall disease burden was consistent with stage IV Burkitt lymphoma. R-miniCHOP chemotherapy—rituximab plus a reduced dose of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone—was initiated. Approximately 2 weeks after chemotherapy was initiated, the patient developed a firm erythematous eruption on the left hip (Figure 1A). His regimen was then switched to R-EPOCH—rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin—at the time of discharge, and he was referred to dermatology due to an initial concern of an adverse reaction to R-EPOCH chemotherapy. The patient denied any pain, pruritus, or irritation. Physical examination showed multifocal, subcutaneous, indurated, erythematous and violaceous nodules without epidermal changes. Some nodules on the lateral aspect of the hip coalesced to form firm plaques.

A punch biopsy specimen showed markedly atypical lymphocytes with enlarged nuclei and scant cytoplasm present throughout the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). Numerous apoptotic cells and cellular debris were seen. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that the lymphocytic infiltrate comprised CD79a+ B cells that were positive for Bcl-6 and CD10 and negative for Bcl-2 (Figures 2C and 2D). There also was diminished focal expression of CD20. Ki-67 protein staining was intensely positive and demonstrated a very high proliferative index.

Taken together, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of Burkitt lymphoma. The patient’s cutaneous lesions improved after continued aggressive chemotherapy. At follow-up 2 weeks after biopsy, he was receiving his second round of R-EPOCH chemotherapy with appreciable regression of skin lesions (Figure 1B). However, he then developed right-side double vision, ptosis, and right-side facial paresthesia. Although magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and lumbar puncture did not show evidence of central nervous system involvement, the chemotherapy regimen was switched to dose-adjusted CVAD-R—hypercyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin hydrochloride, and dexamethasone plus rituximab—for empiric treatment of central nervous system disease. Although treatment was complicated by sepsis with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacter cloacae, Burkitt lymphoma was found to be in remission after 3 cycles of CVAD-R and 5 months of chemotherapy.

Burkitt lymphoma is a B-cell non-Hodgkin malignancy caused by translocation of chromosome 8 and chromosome 14, leading to overexpression of c-MYC and subsequent hyperproliferation of B lymphocytes.1,2 The disease is divided into 3 major categories: sporadic, endemic, and immunodeficiency related.3 The endemic variant is the most prevalent subtype in Africa and is associated with Plasmodium falciparum malaria; the sporadic variant is the most common subtype in the rest of the world.4

Burkitt lymphoma is highly aggressive and is characterized by unusually high rates of mitosis and apoptosis that result in abundant cellular debris and a distinctive starry-sky pattern on histopathology.5,6 Extranodal metastasis is common,7 but cutaneous involvement is exceedingly rare, with only a few cases having been reported.8-14 Cutaneous metastasis of Burkitt lymphoma often is associated with a high overall disease burden and poor prognosis.8,11

Immunodeficiency-related Burkitt lymphoma is particularly aggressive. Notably, 3 of 7 (42.9%) reported cases of cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma occurred in HIV-positive patients.11,13 In one case, cutaneous involvement was the first sign of relapsed disease that had been in remission.12

Although c-MYC rearrangement is required to make a diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma, the disease also is present in a minority of cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)(6%).15 Although DLBCL typically can be differentiated from Burkitt lymphoma by the large nuclear size and characteristic vesicular nuclei of B cells, few cases of DLBCL with c-MYC rearrangement histologically mimic Burkitt lymphoma. However, key features such as immunohistochemical staining for Bcl-2 and CD10 can be used to distinguish these 2 entities.16 Bcl-2 negativity and CD10 positivity, as seen in our patient, is considered more characteristic of Burkitt lymphoma. This staining pattern in combination with a high Ki-67 fraction (>95%) and the presence of monomorphic medium-sized cells is more consistent with a diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma than of DLBCL.17

Earlier case reports have documented that cutaneous lesions of Burkitt lymphoma can occur in a variety of ways. Hematogenous spread is the likely route of metastasis for lesions distant to the primary site or those that have widespread distribution.18 Alternatively, other reports have suggested that cutaneous metastases can occur from local invasion and subcutaneous extension of malignant cells after a surgical procedure.10,19 For example, cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma has been reported in the setting of celioscopy, occurring directly at the surgical site.19 In our patient, we believe that the route of metastatic spread likely was through subcutaneous invasion secondary to CT-guided core biopsy, which was supported by the observation that the onset of cutaneous manifestations was temporally related to the procedure and that the lesions occurred on the skin directly overlying the biopsy site.

In conclusion, we describe an exceedingly rare presentation of cutaneous Burkitt lymphoma in which a surgical procedure likely served as an inciting event that triggered seeding of malignant cells to the skin. Cutaneous spread of Burkitt lymphoma is infrequently reported; all such reports that provide long-term follow-up data have described it in association with high disease burden and often a lethal outcome.8,11,12 Our patient had complete resolution of cutaneous lesions with chemotherapy. It is unclear if the presence of cutaneous lesions can serve as a prognostic indicator and requires further investigation. However, our case provides preliminary evidence to suggest that cutaneous metastases do not always represent aggressive disease and that cutaneous lesions may respond well to chemotherapy.

- Kalisz K, Alessandrino F, Beck R, et al. An update on Burkitt lymphoma: a review of pathogenesis and multimodality imaging assessment of disease presentation, treatment response, and recurrence. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:56. doi:10.1186/s13244-019-0733-7

- Dunleavy K, Gross TG. Management of aggressive B-cell NHLs in the AYA population: an adult vs pediatric perspective. Blood. 2018;132:369-375. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-02-778480

- Noy A. Burkitt lymphoma—subtypes, pathogenesis, and treatment strategies. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(Suppl 1):S37-S38. doi:10.1016/S2152-2650(20)30455-9

- Lenze D, Leoncini L, Hummel M, et al. The different epidemiologic subtypes of Burkitt lymphoma share a homogenous micro RNA profile distinct from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2011;25:1869-1876. doi:10.1038/leu.2011.156

- Bellan C, Lazzi S, De Falco G, et al. Burkitt’s lymphoma: new insights into molecular pathogenesis. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:188-192. doi:10.1136/jcp.56.3.188

- Chuang S-S, Ye H, Du M-Q, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry in distinguishing Burkitt lymphoma from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with very high proliferation index and with or without a starry-sky pattern: a comparative study with EBER and FISH. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:558-564. doi:10.1309/EQJR3D3V0CCQGP04

- Baker PS, Gold KG, Lane KA, et al. Orbital burkitt lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: a report of 3 cases and a review of the literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:464-468. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b80fde

- Fuhrmann TL, Ignatovich YV, Pentland A. Cutaneous metastatic disease: Burkitt lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1196-1197. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.033

- Burns CA, Scott GA, Miller CC. Leukemia cutis at the site of trauma in a patient with Burkitt leukemia. Cutis. 2005;75:54-56.

- Jacobson MA, Hutcheson ACS, Hurray DH, et al. Cutaneous involvement by Burkitt lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1111-1113. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.02.030

- Berk DR, Cheng A, Lind AC, et al. Burkitt lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Bachmeyer C, Bazarbachi A, Rio B, et al. Specific cutaneous involvement indicating relapse of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 1997;54:176. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199702)54:2<176::aid-ajh20>3.0.co;2-c

- Rogers A, Graves M, Toscano M, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of Burkitt lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:997-1001. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000004

- Thakkar D, Lipi L, Misra R, et al. Skin involvement in Burkitt’s lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2018;11:251-252. doi:10.1016/j.hemonc.2018.01.002

- Akasaka T, Akasaka H, Ueda C, et al. Molecular and clinical features of non-Burkitt’s, diffuse large-cell lymphoma of B-cell type associated with the c-MYC/immunoglobulin heavy-chain fusion gene. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:510-518. doi:10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.510

- Nakamura N, Nakamine H, Tamaru J-I, et al. The distinction between Burkitt lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with c-myc rearrangement. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:771-776. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000019577.73786.64

- Bellan C, Stefano L, Giulia de F, et al. Burkitt lymphoma versus diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a practical approach. Hematol Oncol. 2010;28:53-56. doi:10.1002/hon.916

- Amonchaisakda N, Aiempanakit K, Apinantriyo B. Burkitt lymphoma initially mimicking varicella zoster infection. IDCases. 2020;21:E00818. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00818

- Aractingi S, Marolleau JP, Daniel MT, et al. Subcutaneous localizations of Burkitt lymphoma after celioscopy. Am J Hematol. 1993;42:408. doi:10.1002/ajh.2830420421

- Kalisz K, Alessandrino F, Beck R, et al. An update on Burkitt lymphoma: a review of pathogenesis and multimodality imaging assessment of disease presentation, treatment response, and recurrence. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:56. doi:10.1186/s13244-019-0733-7

- Dunleavy K, Gross TG. Management of aggressive B-cell NHLs in the AYA population: an adult vs pediatric perspective. Blood. 2018;132:369-375. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-02-778480

- Noy A. Burkitt lymphoma—subtypes, pathogenesis, and treatment strategies. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(Suppl 1):S37-S38. doi:10.1016/S2152-2650(20)30455-9

- Lenze D, Leoncini L, Hummel M, et al. The different epidemiologic subtypes of Burkitt lymphoma share a homogenous micro RNA profile distinct from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2011;25:1869-1876. doi:10.1038/leu.2011.156

- Bellan C, Lazzi S, De Falco G, et al. Burkitt’s lymphoma: new insights into molecular pathogenesis. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:188-192. doi:10.1136/jcp.56.3.188

- Chuang S-S, Ye H, Du M-Q, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry in distinguishing Burkitt lymphoma from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with very high proliferation index and with or without a starry-sky pattern: a comparative study with EBER and FISH. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:558-564. doi:10.1309/EQJR3D3V0CCQGP04

- Baker PS, Gold KG, Lane KA, et al. Orbital burkitt lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: a report of 3 cases and a review of the literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:464-468. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b80fde

- Fuhrmann TL, Ignatovich YV, Pentland A. Cutaneous metastatic disease: Burkitt lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1196-1197. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.033

- Burns CA, Scott GA, Miller CC. Leukemia cutis at the site of trauma in a patient with Burkitt leukemia. Cutis. 2005;75:54-56.

- Jacobson MA, Hutcheson ACS, Hurray DH, et al. Cutaneous involvement by Burkitt lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1111-1113. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.02.030

- Berk DR, Cheng A, Lind AC, et al. Burkitt lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:14.

- Bachmeyer C, Bazarbachi A, Rio B, et al. Specific cutaneous involvement indicating relapse of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 1997;54:176. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199702)54:2<176::aid-ajh20>3.0.co;2-c

- Rogers A, Graves M, Toscano M, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of Burkitt lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:997-1001. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000004

- Thakkar D, Lipi L, Misra R, et al. Skin involvement in Burkitt’s lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2018;11:251-252. doi:10.1016/j.hemonc.2018.01.002

- Akasaka T, Akasaka H, Ueda C, et al. Molecular and clinical features of non-Burkitt’s, diffuse large-cell lymphoma of B-cell type associated with the c-MYC/immunoglobulin heavy-chain fusion gene. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:510-518. doi:10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.510

- Nakamura N, Nakamine H, Tamaru J-I, et al. The distinction between Burkitt lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with c-myc rearrangement. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:771-776. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000019577.73786.64

- Bellan C, Stefano L, Giulia de F, et al. Burkitt lymphoma versus diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a practical approach. Hematol Oncol. 2010;28:53-56. doi:10.1002/hon.916

- Amonchaisakda N, Aiempanakit K, Apinantriyo B. Burkitt lymphoma initially mimicking varicella zoster infection. IDCases. 2020;21:E00818. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00818

- Aractingi S, Marolleau JP, Daniel MT, et al. Subcutaneous localizations of Burkitt lymphoma after celioscopy. Am J Hematol. 1993;42:408. doi:10.1002/ajh.2830420421

Practice Points

- Cutaneous metastasis is exceedingly rare in Burkitt lymphoma. When cutaneous involvement does occur, it can represent an uncommon consequence of a surgical procedure, serving as the inciting event for hematogenous spread and local tumor extension into the skin.

- Although cutaneous metasis of Burkitt lymphoma typically is associated with high disease burden and mortality, our case demonstrated that cutaneous spread can be present even in a patient who has a positive outcome. Our patient was able to achieve disease remission and complete resolution of cutaneous lesions with continued chemotherapy, suggesting that cutaneous metastasis does not always portend a poor prognosis.

Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: Cutaneous Associations in Women With Skin of Color

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) has been reported in association with lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) and facial papules.1-3 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a variant of lichen planus that causes hyperpigmentation of the face, neck, and/or intertriginous areas that may be useful as a clinical indicator in the development of FFA.1 Facial papules in association with FFA are secondary to fibrosed vellus hairs.2,3 Currently, reports of concomitant FFA, LPP, and facial papules in women with skin of color are limited in the literature. This case series includes 5 women of color (Hispanic and black) who presented to our clinic with FFA and various cutaneous associations. A review of the current literature on cutaneous associations of FFA also is provided.

Case Reports

Patient 1

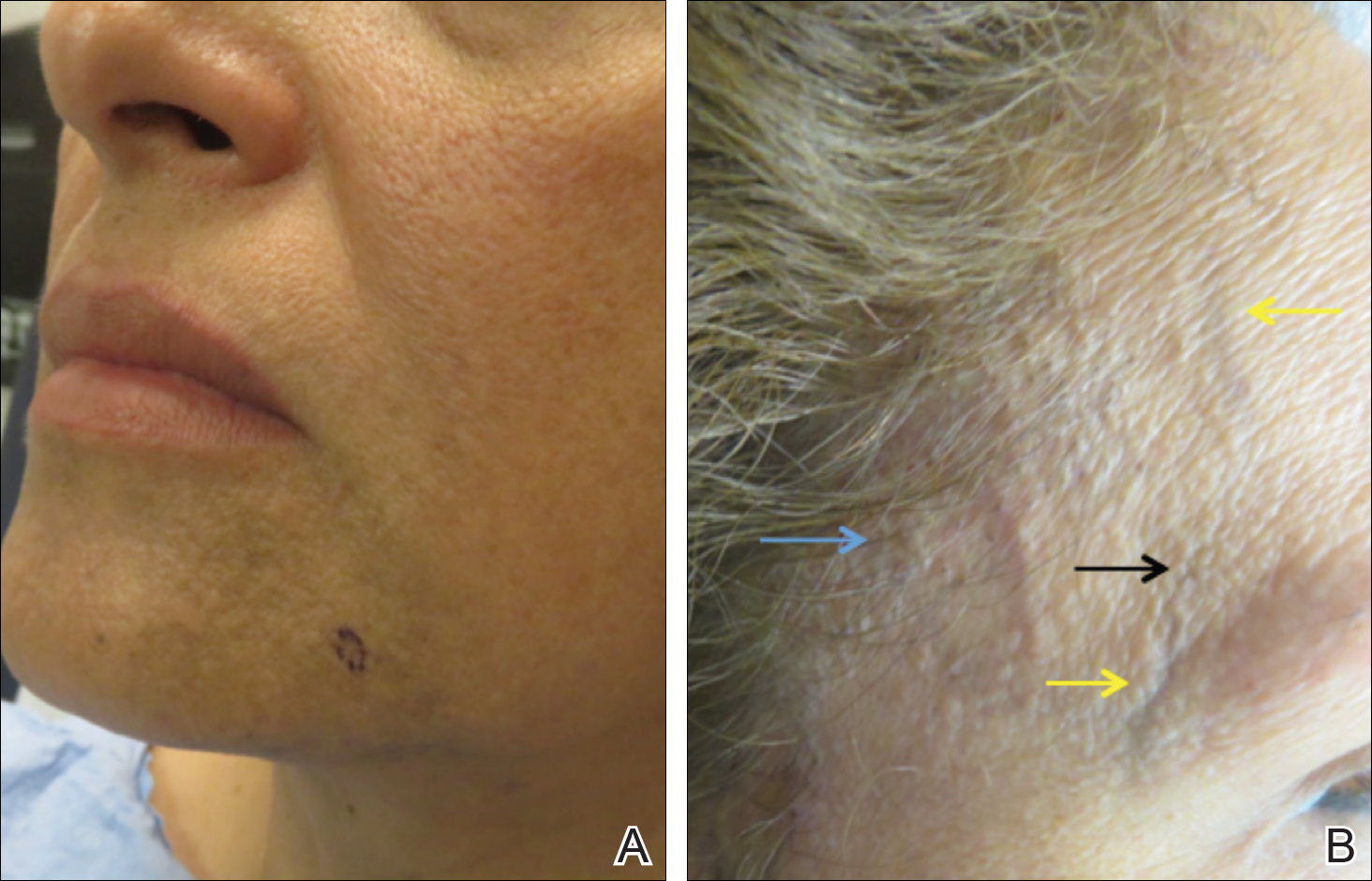

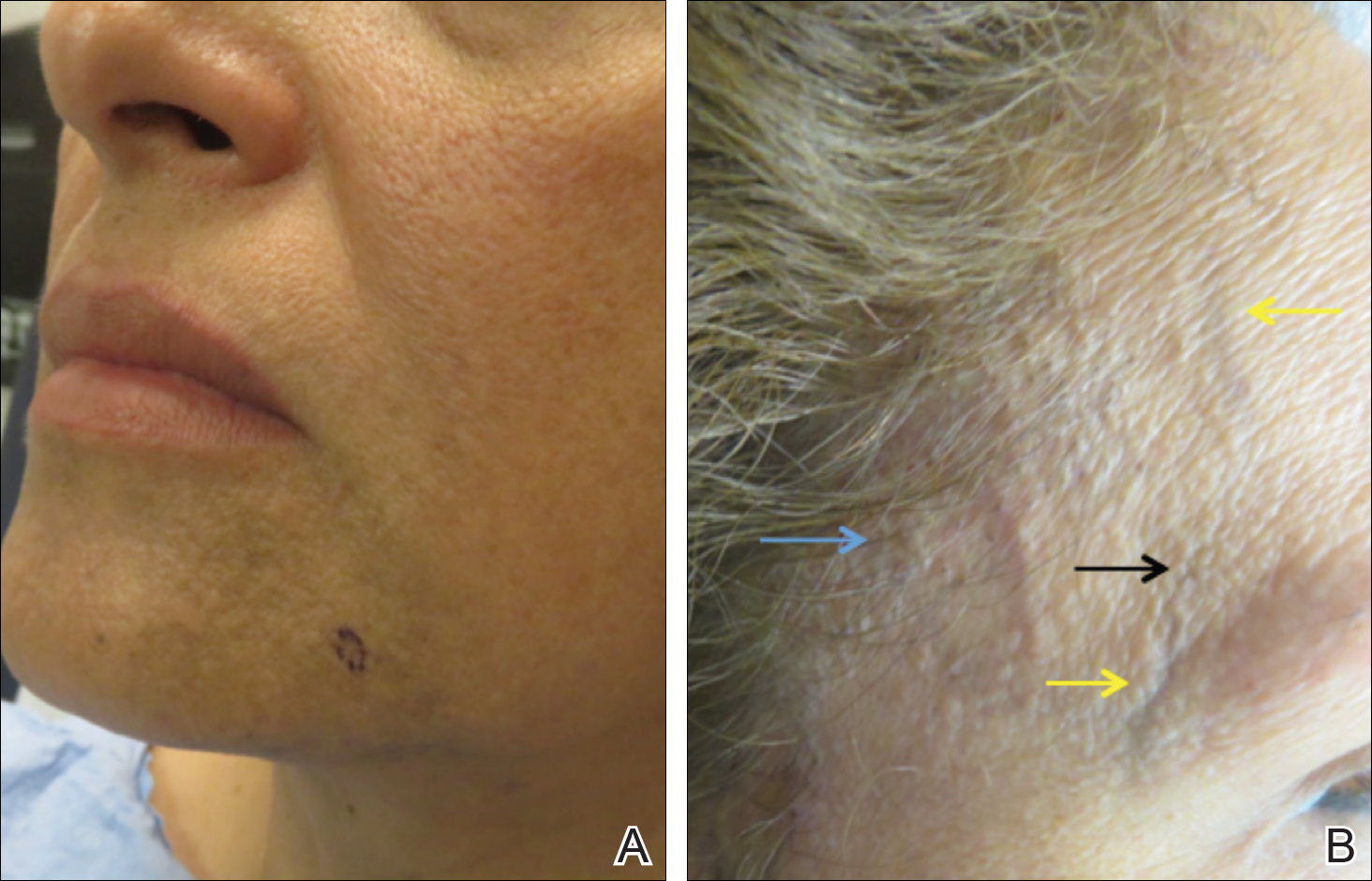

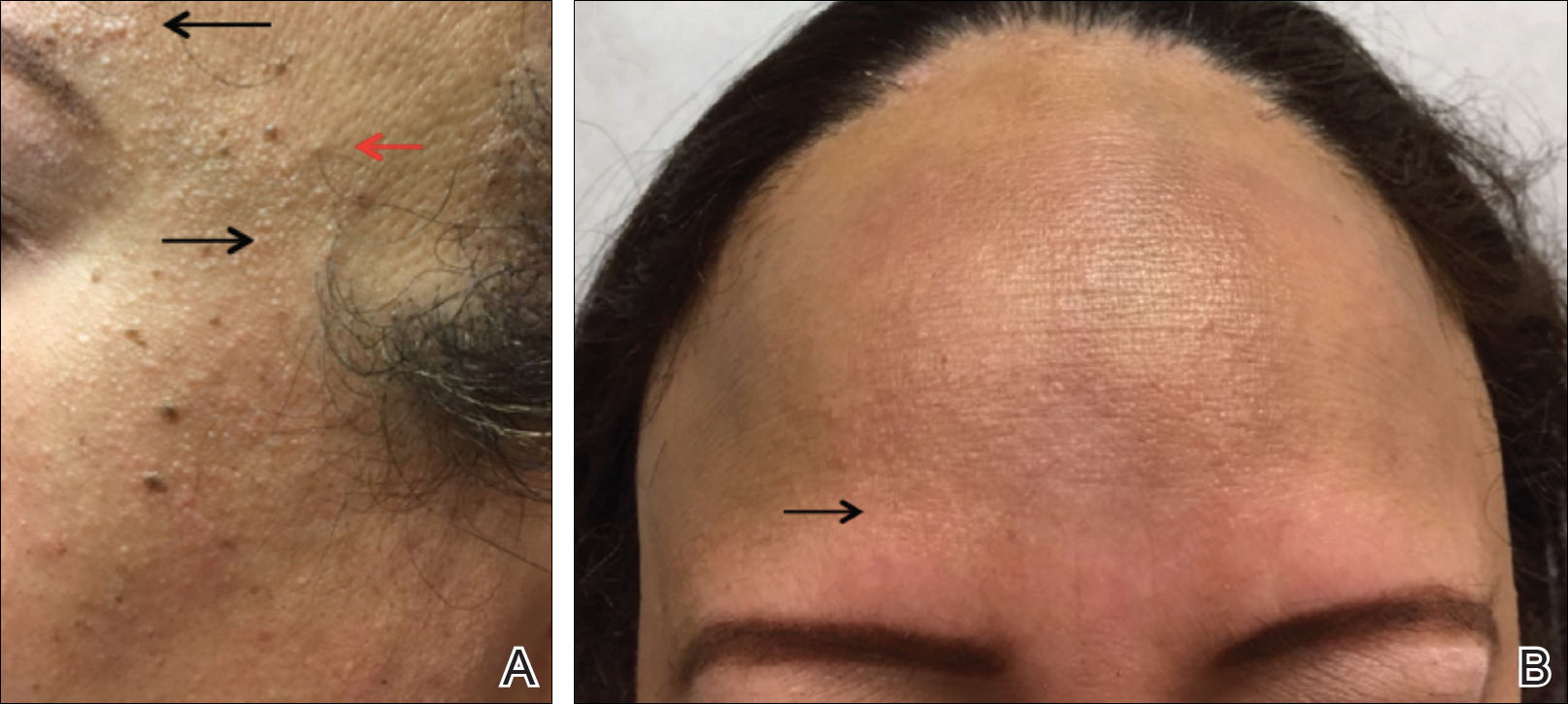

A 50-year-old Hispanic woman who was previously presumed to have melasma by an outside physician presented with pruritus of the scalp and eyebrows of 1 month’s duration. Physical examination revealed decreased frontal scalp hair density with perifollicular erythema and scale with thinning of the lateral eyebrows. Hyperpigmented coalesced macules (Figure 1A) and erythematous perifollicular papules were noted along the temples and on the perioral skin. Depressed forehead and temporal veins also were noted (Figure 1B). A biopsy of the scalp demonstrated perifollicular and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and fibrosed hair follicles, and a biopsy of the perioral skin demonstrated perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with melanophages in the papillary dermis. A diagnosis of FFA with LPP was established with these biopsies.

Patient 2

A 61-year-old black woman presented with asymptomatic hair loss along the frontal hairline for an unknown duration. On physical examination the frontal scalp and lateral eyebrows demonstrated decreased hair density with loss of follicular ostia. Fine, flesh-colored, monomorphic papules were scattered along the forehead and temples, and ill-defined brown pigmentation was present along the forehead, temples, and cheeks. Biopsy of the frontal scalp demonstrated patchy lichenoid inflammation with decreased number of follicles with replacement by follicular scars, confirming the diagnosis of FFA.

Patient 3

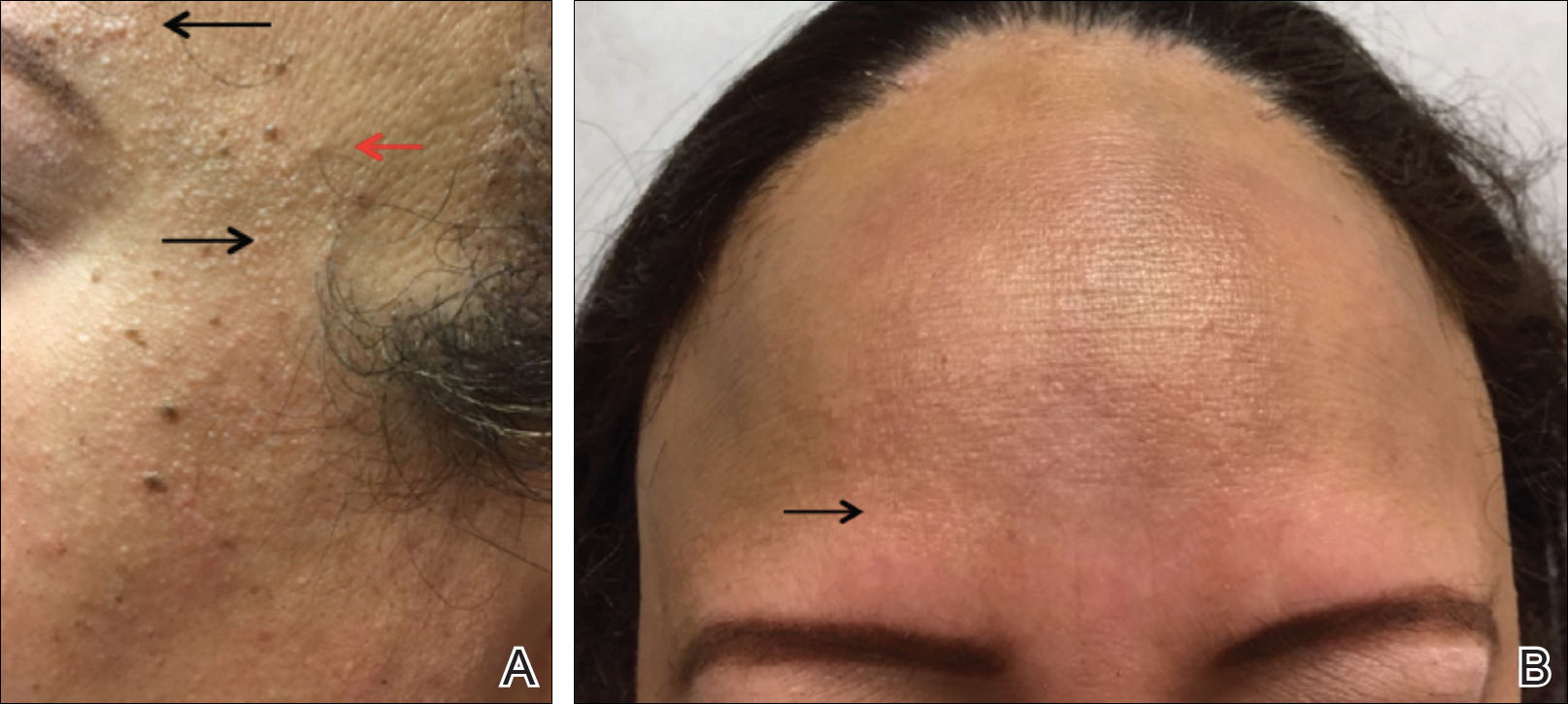

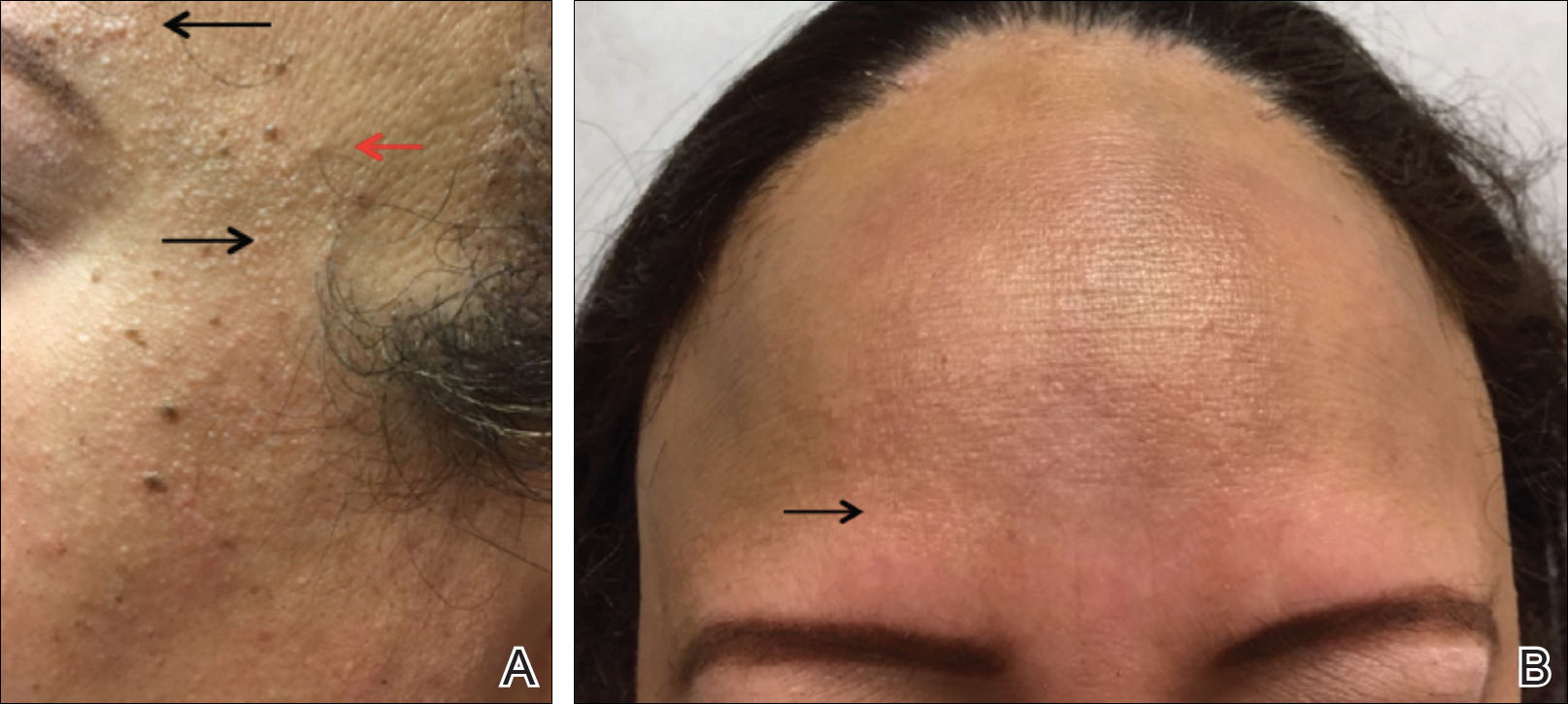

A 47-year-old Hispanic woman presented with hair loss of the frontal scalp and bilateral eyebrows with associated burning of 2 years’ duration. Physical examination demonstrated recession of the frontotemporal hairline with scattered lone hairs and thinning of the eyebrows. Innumerable flesh-colored papules were present on the forehead and temples (Figure 2A). Glabellar and eyebrow erythema was noted (Figure 2B). Biopsy of the frontal scalp demonstrated decreased terminal anagen hair follicles with perifollicular lymphoid infiltrate and fibrosis, consistent with a diagnosis of FFA. The patient was started on oral hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily, and 3 months later hyperpigmentation of the forehead and perioral skin was noted. The patient reported that she had facial hyperpigmentation prior to starting hydroxychloroquine and declined a biopsy.

Patient 4

A 40-year-old black woman presented with brown pruritic macles of the face, neck, arms, and forearms of 4 years’ duration. She also reported hair loss on the frontal and occipital scalp, eyebrows, and arms. On physical examination, ill-defined brown macules and patches were noted on the neck (Figure 3), face, arms, and forearms. Decreased hair density was noted on the frontal and occipital scalp with follicular dropout and perifollicular hyperpigmentation. Biopsy of the scalp demonstrated perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with sparse anagen follicles and fibrous tracts, and biopsy of the neck revealed superficial perivascular inflammation with numerous melanophages in the upper dermis; these histopathologic findings were consistent with FFA and LPP, respectively.

Patient 5

A 46-year-old black woman with history of hair loss presented with hyperpigmentation of the face and neck of 2 years’ duration. On physical examination decreased hair density of the frontal and vertex scalp and lateral eyebrows was noted. Flesh-colored papules were noted on the forehead and cheeks, and confluent dark brown patches were present on the temples and neck. Three punch biopsies were performed. Biopsy of the scalp revealed lymphocytic inflammation with surrounding fibroplasia with overlapping features of FFA and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (Figure 4). Biopsy of the neck revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis. Additionally, biopsy of a facial papule revealed lichenoid inflammation involving a vellus hair follicle. Clinical and histopathological correlation confirmed the diagnosis of FFA with LPP and facial papules.

Comment

Current understanding of FFA as a progressive, lymphocytic, scarring alopecia has expanded in recent years. Clinical observation suggests that the incidence of FFA is increasing4; however more epidemiologic data are needed. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presents clinically with symmetrical frontotemporal hair loss with lone hairs. Trichoscopy reveals perifollicular hyperkeratosis, perifollicular erythema, and follicular plugging in 72%, 66%, and 44% of cases, respectively.5 In one study (N=242), patients were classified into 3 clinical patterns of FFA: pattern I (linear) showed bandlike loss of frontal hair with normal density directly behind the hairline; pattern II (diffuse) showed loss of density behind the frontal hairline; and pattern III (double line) showed a pseudo–“fringe sign” appearance. The majority of patients were classified as either pattern I or II, with pattern II predicting a poorer prognosis.6

rontal fibrosing alopecia is increasingly recognized in men, with prevalence as high as 5%.1 Facial hair involvement, particularly of the upper lip and sideburns, is an important consideration in men.7 Most studies suggest that 80% to 90% of affected women are postmenopausal,8 though a case series presented by Dlova1 identified 27% of affected women as postmenopausal. The coexistence of premature menopause and hysterectomy in FFA patients suggests a hormonal contribution, but this association is still poorly understood.8 Epidemiologic data on ethnicity in FFA are sparse but suggest that white individuals are more likely to be affected. Frontal fibrosing alopecia also may be misdiagnosed as traction alopecia in Hispanic and black patients.8

It is prudent for physicians to assess for and recognize clinical clues to severe forms of FFA. A 2014 multicenter review of 355 patients identified 3 clinical entities that predicted more severe forms of FFA: eyelash loss (madarosis), loss of body hair, and facial papules.8 Madarosis occurs due to perifollicular inflammation and fibrosis of eyelash hair follicles. Similarly, perifollicular inflammation of body hair was present in 24% of patients (N=86), most commonly of the axillary and pubic hair. Facial papules form due to facial vellus hair inflammation and fibrosis and were identified in 14% of patients (N=49).8 These clinical findings may allow providers to predict more extensive clinical involvement of FFA.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia and LPP occur concomitantly in up 54% of patients, more commonly in darker-skinned patients.1,9,10 Lichen planus pigmentosus frequently occurs on the face and neck, most commonly in a diffuse pattern, though reticulated and macular patterns also have been identified.11 In some patients, LPP precedes the development of FFA and may be useful as a herald sign1; therefore, it is important for dermatologists to evaluate for signs of FFA when evaluating those with LPP. Thorough evaluation in patients with skin of color also is important because FFA may be misdiagnosed as traction alopecia.

Additional cutaneous associations of FFA include eyebrow loss, glabellar red dots, and prominent frontal veins. Eyebrow loss occurs secondary to fibrosis of eyebrow hair follicles and has been found in 40% to 80% of patients with FFA; it is thought to be associated with milder forms of FFA.8 Glabellar red dots correlate with histopathologic lymphocytic inflammation of vellus hair follicles.12 Additionally, frontal vein prominence has been described in FFA and is thought to be secondary to atrophy in this scarring process, perhaps worsened by local steroid treatments.13 Mucocutaneous lichen planus, rosacea, thyroid disease, vitiligo, and other autoimmune disorders also have been reported in patients with FFA.14

Conclusion

Concomitant FFA, LPP, and facial papules have been rarely reported and exemplify the spectrum of cutaneous associations with FFA, particularly in individuals with skin of color. Clinical variants and associations of FFA are broad, including predictors of poorer prognosis such as eyelash loss and vellus hair involvement seen as facial papules. Lichen planus pigmentosus is well described in association with FFA and may serve as a herald sign that frontal hair loss should not be mistaken for traction alopecia in early stages. Eyebrow loss is thought to represent milder disease. It is important for dermatologists to be aware of these findings to understand the breadth of this disease and for appropriate evaluation and management of patients with FFA.

- Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:439-432.

- Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, et al. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424-1427.

- Tan KT, Messenger AG. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: clinical presentations and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:75-79.

- Rudnicka L, Rakowska A. The increasing incidence of frontal fibrosing alopecia. in search of triggering factors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1579-1580.

- Toledo-Pastrana T, Hernández MJ, Camacho Martínez FM. Perifollicular erythema as a trichoscopy sign of progression in frontal fibrosing alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:151-153.

- Moreno-Arrones OM, Saceda-Corralo D, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: clinical and prognostic classification. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1739-1745.

- Tolkachjov SN, Chaudhry HM, Camilleri MJ, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia among men: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:683-690.e2.

- Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

- Berliner JG, McCalmont TH, Price VH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E26-E27.

- Rao R, Sarda A, Khanna R, et al. Coexistence of frontal fibrosing alopecia with lichen planus pigmentosus. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:622-624.

- Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1387-1390.

- Pirmez R, Donati A, Valente NS, et al. Glabellar red dots in frontal fibrosing alopecia: a further clinical sign of vellus follicle involvement. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:745-746.

- Vañó-Galván S, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Urech M, et al. Depression of the frontal veins: a new clinical sign of frontal fibrosing alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1087-1088.

- Pindado-Ortega C, Saceda-Corralo D, Buendía-Castaño D, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and cutaneous comorbidities: a potential relationship with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:596-597.e1.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) has been reported in association with lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) and facial papules.1-3 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a variant of lichen planus that causes hyperpigmentation of the face, neck, and/or intertriginous areas that may be useful as a clinical indicator in the development of FFA.1 Facial papules in association with FFA are secondary to fibrosed vellus hairs.2,3 Currently, reports of concomitant FFA, LPP, and facial papules in women with skin of color are limited in the literature. This case series includes 5 women of color (Hispanic and black) who presented to our clinic with FFA and various cutaneous associations. A review of the current literature on cutaneous associations of FFA also is provided.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 50-year-old Hispanic woman who was previously presumed to have melasma by an outside physician presented with pruritus of the scalp and eyebrows of 1 month’s duration. Physical examination revealed decreased frontal scalp hair density with perifollicular erythema and scale with thinning of the lateral eyebrows. Hyperpigmented coalesced macules (Figure 1A) and erythematous perifollicular papules were noted along the temples and on the perioral skin. Depressed forehead and temporal veins also were noted (Figure 1B). A biopsy of the scalp demonstrated perifollicular and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and fibrosed hair follicles, and a biopsy of the perioral skin demonstrated perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with melanophages in the papillary dermis. A diagnosis of FFA with LPP was established with these biopsies.

Patient 2

A 61-year-old black woman presented with asymptomatic hair loss along the frontal hairline for an unknown duration. On physical examination the frontal scalp and lateral eyebrows demonstrated decreased hair density with loss of follicular ostia. Fine, flesh-colored, monomorphic papules were scattered along the forehead and temples, and ill-defined brown pigmentation was present along the forehead, temples, and cheeks. Biopsy of the frontal scalp demonstrated patchy lichenoid inflammation with decreased number of follicles with replacement by follicular scars, confirming the diagnosis of FFA.

Patient 3

A 47-year-old Hispanic woman presented with hair loss of the frontal scalp and bilateral eyebrows with associated burning of 2 years’ duration. Physical examination demonstrated recession of the frontotemporal hairline with scattered lone hairs and thinning of the eyebrows. Innumerable flesh-colored papules were present on the forehead and temples (Figure 2A). Glabellar and eyebrow erythema was noted (Figure 2B). Biopsy of the frontal scalp demonstrated decreased terminal anagen hair follicles with perifollicular lymphoid infiltrate and fibrosis, consistent with a diagnosis of FFA. The patient was started on oral hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily, and 3 months later hyperpigmentation of the forehead and perioral skin was noted. The patient reported that she had facial hyperpigmentation prior to starting hydroxychloroquine and declined a biopsy.

Patient 4

A 40-year-old black woman presented with brown pruritic macles of the face, neck, arms, and forearms of 4 years’ duration. She also reported hair loss on the frontal and occipital scalp, eyebrows, and arms. On physical examination, ill-defined brown macules and patches were noted on the neck (Figure 3), face, arms, and forearms. Decreased hair density was noted on the frontal and occipital scalp with follicular dropout and perifollicular hyperpigmentation. Biopsy of the scalp demonstrated perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with sparse anagen follicles and fibrous tracts, and biopsy of the neck revealed superficial perivascular inflammation with numerous melanophages in the upper dermis; these histopathologic findings were consistent with FFA and LPP, respectively.

Patient 5

A 46-year-old black woman with history of hair loss presented with hyperpigmentation of the face and neck of 2 years’ duration. On physical examination decreased hair density of the frontal and vertex scalp and lateral eyebrows was noted. Flesh-colored papules were noted on the forehead and cheeks, and confluent dark brown patches were present on the temples and neck. Three punch biopsies were performed. Biopsy of the scalp revealed lymphocytic inflammation with surrounding fibroplasia with overlapping features of FFA and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (Figure 4). Biopsy of the neck revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis. Additionally, biopsy of a facial papule revealed lichenoid inflammation involving a vellus hair follicle. Clinical and histopathological correlation confirmed the diagnosis of FFA with LPP and facial papules.

Comment

Current understanding of FFA as a progressive, lymphocytic, scarring alopecia has expanded in recent years. Clinical observation suggests that the incidence of FFA is increasing4; however more epidemiologic data are needed. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presents clinically with symmetrical frontotemporal hair loss with lone hairs. Trichoscopy reveals perifollicular hyperkeratosis, perifollicular erythema, and follicular plugging in 72%, 66%, and 44% of cases, respectively.5 In one study (N=242), patients were classified into 3 clinical patterns of FFA: pattern I (linear) showed bandlike loss of frontal hair with normal density directly behind the hairline; pattern II (diffuse) showed loss of density behind the frontal hairline; and pattern III (double line) showed a pseudo–“fringe sign” appearance. The majority of patients were classified as either pattern I or II, with pattern II predicting a poorer prognosis.6

rontal fibrosing alopecia is increasingly recognized in men, with prevalence as high as 5%.1 Facial hair involvement, particularly of the upper lip and sideburns, is an important consideration in men.7 Most studies suggest that 80% to 90% of affected women are postmenopausal,8 though a case series presented by Dlova1 identified 27% of affected women as postmenopausal. The coexistence of premature menopause and hysterectomy in FFA patients suggests a hormonal contribution, but this association is still poorly understood.8 Epidemiologic data on ethnicity in FFA are sparse but suggest that white individuals are more likely to be affected. Frontal fibrosing alopecia also may be misdiagnosed as traction alopecia in Hispanic and black patients.8

It is prudent for physicians to assess for and recognize clinical clues to severe forms of FFA. A 2014 multicenter review of 355 patients identified 3 clinical entities that predicted more severe forms of FFA: eyelash loss (madarosis), loss of body hair, and facial papules.8 Madarosis occurs due to perifollicular inflammation and fibrosis of eyelash hair follicles. Similarly, perifollicular inflammation of body hair was present in 24% of patients (N=86), most commonly of the axillary and pubic hair. Facial papules form due to facial vellus hair inflammation and fibrosis and were identified in 14% of patients (N=49).8 These clinical findings may allow providers to predict more extensive clinical involvement of FFA.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia and LPP occur concomitantly in up 54% of patients, more commonly in darker-skinned patients.1,9,10 Lichen planus pigmentosus frequently occurs on the face and neck, most commonly in a diffuse pattern, though reticulated and macular patterns also have been identified.11 In some patients, LPP precedes the development of FFA and may be useful as a herald sign1; therefore, it is important for dermatologists to evaluate for signs of FFA when evaluating those with LPP. Thorough evaluation in patients with skin of color also is important because FFA may be misdiagnosed as traction alopecia.

Additional cutaneous associations of FFA include eyebrow loss, glabellar red dots, and prominent frontal veins. Eyebrow loss occurs secondary to fibrosis of eyebrow hair follicles and has been found in 40% to 80% of patients with FFA; it is thought to be associated with milder forms of FFA.8 Glabellar red dots correlate with histopathologic lymphocytic inflammation of vellus hair follicles.12 Additionally, frontal vein prominence has been described in FFA and is thought to be secondary to atrophy in this scarring process, perhaps worsened by local steroid treatments.13 Mucocutaneous lichen planus, rosacea, thyroid disease, vitiligo, and other autoimmune disorders also have been reported in patients with FFA.14

Conclusion

Concomitant FFA, LPP, and facial papules have been rarely reported and exemplify the spectrum of cutaneous associations with FFA, particularly in individuals with skin of color. Clinical variants and associations of FFA are broad, including predictors of poorer prognosis such as eyelash loss and vellus hair involvement seen as facial papules. Lichen planus pigmentosus is well described in association with FFA and may serve as a herald sign that frontal hair loss should not be mistaken for traction alopecia in early stages. Eyebrow loss is thought to represent milder disease. It is important for dermatologists to be aware of these findings to understand the breadth of this disease and for appropriate evaluation and management of patients with FFA.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) has been reported in association with lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) and facial papules.1-3 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a variant of lichen planus that causes hyperpigmentation of the face, neck, and/or intertriginous areas that may be useful as a clinical indicator in the development of FFA.1 Facial papules in association with FFA are secondary to fibrosed vellus hairs.2,3 Currently, reports of concomitant FFA, LPP, and facial papules in women with skin of color are limited in the literature. This case series includes 5 women of color (Hispanic and black) who presented to our clinic with FFA and various cutaneous associations. A review of the current literature on cutaneous associations of FFA also is provided.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 50-year-old Hispanic woman who was previously presumed to have melasma by an outside physician presented with pruritus of the scalp and eyebrows of 1 month’s duration. Physical examination revealed decreased frontal scalp hair density with perifollicular erythema and scale with thinning of the lateral eyebrows. Hyperpigmented coalesced macules (Figure 1A) and erythematous perifollicular papules were noted along the temples and on the perioral skin. Depressed forehead and temporal veins also were noted (Figure 1B). A biopsy of the scalp demonstrated perifollicular and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and fibrosed hair follicles, and a biopsy of the perioral skin demonstrated perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with melanophages in the papillary dermis. A diagnosis of FFA with LPP was established with these biopsies.

Patient 2

A 61-year-old black woman presented with asymptomatic hair loss along the frontal hairline for an unknown duration. On physical examination the frontal scalp and lateral eyebrows demonstrated decreased hair density with loss of follicular ostia. Fine, flesh-colored, monomorphic papules were scattered along the forehead and temples, and ill-defined brown pigmentation was present along the forehead, temples, and cheeks. Biopsy of the frontal scalp demonstrated patchy lichenoid inflammation with decreased number of follicles with replacement by follicular scars, confirming the diagnosis of FFA.

Patient 3

A 47-year-old Hispanic woman presented with hair loss of the frontal scalp and bilateral eyebrows with associated burning of 2 years’ duration. Physical examination demonstrated recession of the frontotemporal hairline with scattered lone hairs and thinning of the eyebrows. Innumerable flesh-colored papules were present on the forehead and temples (Figure 2A). Glabellar and eyebrow erythema was noted (Figure 2B). Biopsy of the frontal scalp demonstrated decreased terminal anagen hair follicles with perifollicular lymphoid infiltrate and fibrosis, consistent with a diagnosis of FFA. The patient was started on oral hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily, and 3 months later hyperpigmentation of the forehead and perioral skin was noted. The patient reported that she had facial hyperpigmentation prior to starting hydroxychloroquine and declined a biopsy.

Patient 4

A 40-year-old black woman presented with brown pruritic macles of the face, neck, arms, and forearms of 4 years’ duration. She also reported hair loss on the frontal and occipital scalp, eyebrows, and arms. On physical examination, ill-defined brown macules and patches were noted on the neck (Figure 3), face, arms, and forearms. Decreased hair density was noted on the frontal and occipital scalp with follicular dropout and perifollicular hyperpigmentation. Biopsy of the scalp demonstrated perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with sparse anagen follicles and fibrous tracts, and biopsy of the neck revealed superficial perivascular inflammation with numerous melanophages in the upper dermis; these histopathologic findings were consistent with FFA and LPP, respectively.

Patient 5

A 46-year-old black woman with history of hair loss presented with hyperpigmentation of the face and neck of 2 years’ duration. On physical examination decreased hair density of the frontal and vertex scalp and lateral eyebrows was noted. Flesh-colored papules were noted on the forehead and cheeks, and confluent dark brown patches were present on the temples and neck. Three punch biopsies were performed. Biopsy of the scalp revealed lymphocytic inflammation with surrounding fibroplasia with overlapping features of FFA and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (Figure 4). Biopsy of the neck revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis. Additionally, biopsy of a facial papule revealed lichenoid inflammation involving a vellus hair follicle. Clinical and histopathological correlation confirmed the diagnosis of FFA with LPP and facial papules.

Comment

Current understanding of FFA as a progressive, lymphocytic, scarring alopecia has expanded in recent years. Clinical observation suggests that the incidence of FFA is increasing4; however more epidemiologic data are needed. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presents clinically with symmetrical frontotemporal hair loss with lone hairs. Trichoscopy reveals perifollicular hyperkeratosis, perifollicular erythema, and follicular plugging in 72%, 66%, and 44% of cases, respectively.5 In one study (N=242), patients were classified into 3 clinical patterns of FFA: pattern I (linear) showed bandlike loss of frontal hair with normal density directly behind the hairline; pattern II (diffuse) showed loss of density behind the frontal hairline; and pattern III (double line) showed a pseudo–“fringe sign” appearance. The majority of patients were classified as either pattern I or II, with pattern II predicting a poorer prognosis.6

rontal fibrosing alopecia is increasingly recognized in men, with prevalence as high as 5%.1 Facial hair involvement, particularly of the upper lip and sideburns, is an important consideration in men.7 Most studies suggest that 80% to 90% of affected women are postmenopausal,8 though a case series presented by Dlova1 identified 27% of affected women as postmenopausal. The coexistence of premature menopause and hysterectomy in FFA patients suggests a hormonal contribution, but this association is still poorly understood.8 Epidemiologic data on ethnicity in FFA are sparse but suggest that white individuals are more likely to be affected. Frontal fibrosing alopecia also may be misdiagnosed as traction alopecia in Hispanic and black patients.8

It is prudent for physicians to assess for and recognize clinical clues to severe forms of FFA. A 2014 multicenter review of 355 patients identified 3 clinical entities that predicted more severe forms of FFA: eyelash loss (madarosis), loss of body hair, and facial papules.8 Madarosis occurs due to perifollicular inflammation and fibrosis of eyelash hair follicles. Similarly, perifollicular inflammation of body hair was present in 24% of patients (N=86), most commonly of the axillary and pubic hair. Facial papules form due to facial vellus hair inflammation and fibrosis and were identified in 14% of patients (N=49).8 These clinical findings may allow providers to predict more extensive clinical involvement of FFA.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia and LPP occur concomitantly in up 54% of patients, more commonly in darker-skinned patients.1,9,10 Lichen planus pigmentosus frequently occurs on the face and neck, most commonly in a diffuse pattern, though reticulated and macular patterns also have been identified.11 In some patients, LPP precedes the development of FFA and may be useful as a herald sign1; therefore, it is important for dermatologists to evaluate for signs of FFA when evaluating those with LPP. Thorough evaluation in patients with skin of color also is important because FFA may be misdiagnosed as traction alopecia.

Additional cutaneous associations of FFA include eyebrow loss, glabellar red dots, and prominent frontal veins. Eyebrow loss occurs secondary to fibrosis of eyebrow hair follicles and has been found in 40% to 80% of patients with FFA; it is thought to be associated with milder forms of FFA.8 Glabellar red dots correlate with histopathologic lymphocytic inflammation of vellus hair follicles.12 Additionally, frontal vein prominence has been described in FFA and is thought to be secondary to atrophy in this scarring process, perhaps worsened by local steroid treatments.13 Mucocutaneous lichen planus, rosacea, thyroid disease, vitiligo, and other autoimmune disorders also have been reported in patients with FFA.14

Conclusion

Concomitant FFA, LPP, and facial papules have been rarely reported and exemplify the spectrum of cutaneous associations with FFA, particularly in individuals with skin of color. Clinical variants and associations of FFA are broad, including predictors of poorer prognosis such as eyelash loss and vellus hair involvement seen as facial papules. Lichen planus pigmentosus is well described in association with FFA and may serve as a herald sign that frontal hair loss should not be mistaken for traction alopecia in early stages. Eyebrow loss is thought to represent milder disease. It is important for dermatologists to be aware of these findings to understand the breadth of this disease and for appropriate evaluation and management of patients with FFA.

- Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:439-432.

- Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, et al. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424-1427.

- Tan KT, Messenger AG. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: clinical presentations and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:75-79.

- Rudnicka L, Rakowska A. The increasing incidence of frontal fibrosing alopecia. in search of triggering factors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1579-1580.

- Toledo-Pastrana T, Hernández MJ, Camacho Martínez FM. Perifollicular erythema as a trichoscopy sign of progression in frontal fibrosing alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:151-153.

- Moreno-Arrones OM, Saceda-Corralo D, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: clinical and prognostic classification. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1739-1745.

- Tolkachjov SN, Chaudhry HM, Camilleri MJ, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia among men: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:683-690.e2.

- Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

- Berliner JG, McCalmont TH, Price VH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E26-E27.

- Rao R, Sarda A, Khanna R, et al. Coexistence of frontal fibrosing alopecia with lichen planus pigmentosus. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:622-624.

- Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1387-1390.

- Pirmez R, Donati A, Valente NS, et al. Glabellar red dots in frontal fibrosing alopecia: a further clinical sign of vellus follicle involvement. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:745-746.

- Vañó-Galván S, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Urech M, et al. Depression of the frontal veins: a new clinical sign of frontal fibrosing alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1087-1088.

- Pindado-Ortega C, Saceda-Corralo D, Buendía-Castaño D, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and cutaneous comorbidities: a potential relationship with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:596-597.e1.

- Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:439-432.

- Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, et al. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424-1427.

- Tan KT, Messenger AG. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: clinical presentations and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:75-79.

- Rudnicka L, Rakowska A. The increasing incidence of frontal fibrosing alopecia. in search of triggering factors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1579-1580.

- Toledo-Pastrana T, Hernández MJ, Camacho Martínez FM. Perifollicular erythema as a trichoscopy sign of progression in frontal fibrosing alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:151-153.

- Moreno-Arrones OM, Saceda-Corralo D, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: clinical and prognostic classification. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1739-1745.

- Tolkachjov SN, Chaudhry HM, Camilleri MJ, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia among men: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:683-690.e2.

- Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

- Berliner JG, McCalmont TH, Price VH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E26-E27.

- Rao R, Sarda A, Khanna R, et al. Coexistence of frontal fibrosing alopecia with lichen planus pigmentosus. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:622-624.

- Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1387-1390.

- Pirmez R, Donati A, Valente NS, et al. Glabellar red dots in frontal fibrosing alopecia: a further clinical sign of vellus follicle involvement. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:745-746.

- Vañó-Galván S, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Urech M, et al. Depression of the frontal veins: a new clinical sign of frontal fibrosing alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1087-1088.

- Pindado-Ortega C, Saceda-Corralo D, Buendía-Castaño D, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and cutaneous comorbidities: a potential relationship with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:596-597.e1.

Practice Points

- Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is associated with lichen planus pigmentosus, especially in patients with skin of color.

- Patients with FFA should be evaluated for additional cutaneous features including facial papules, glabellar red dots, and depressed frontal veins.