User login

Perceived Benefits of a Research Fellowship for Dermatology Residency Applicants: Outcomes of a Faculty-Reported Survey

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

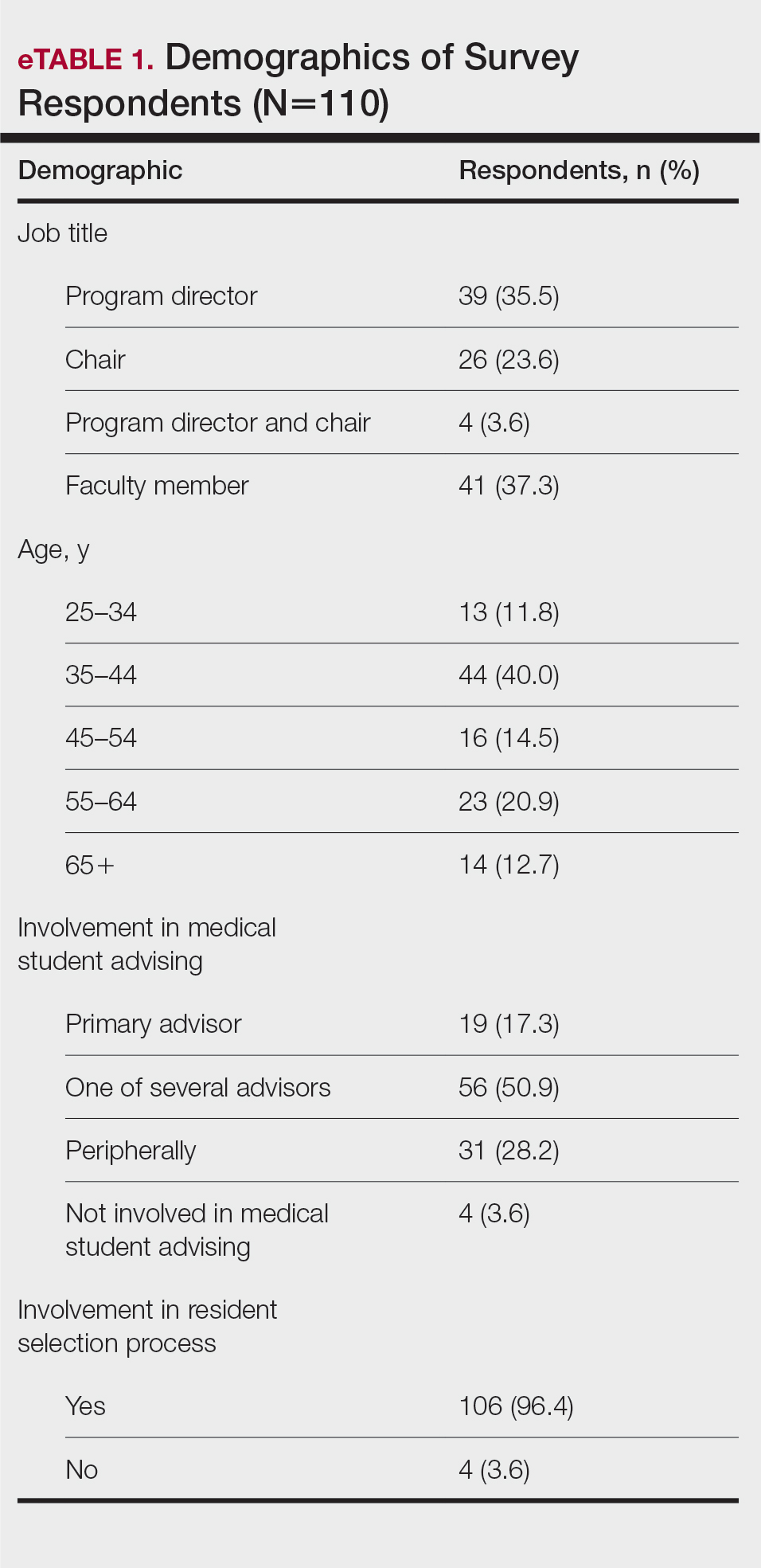

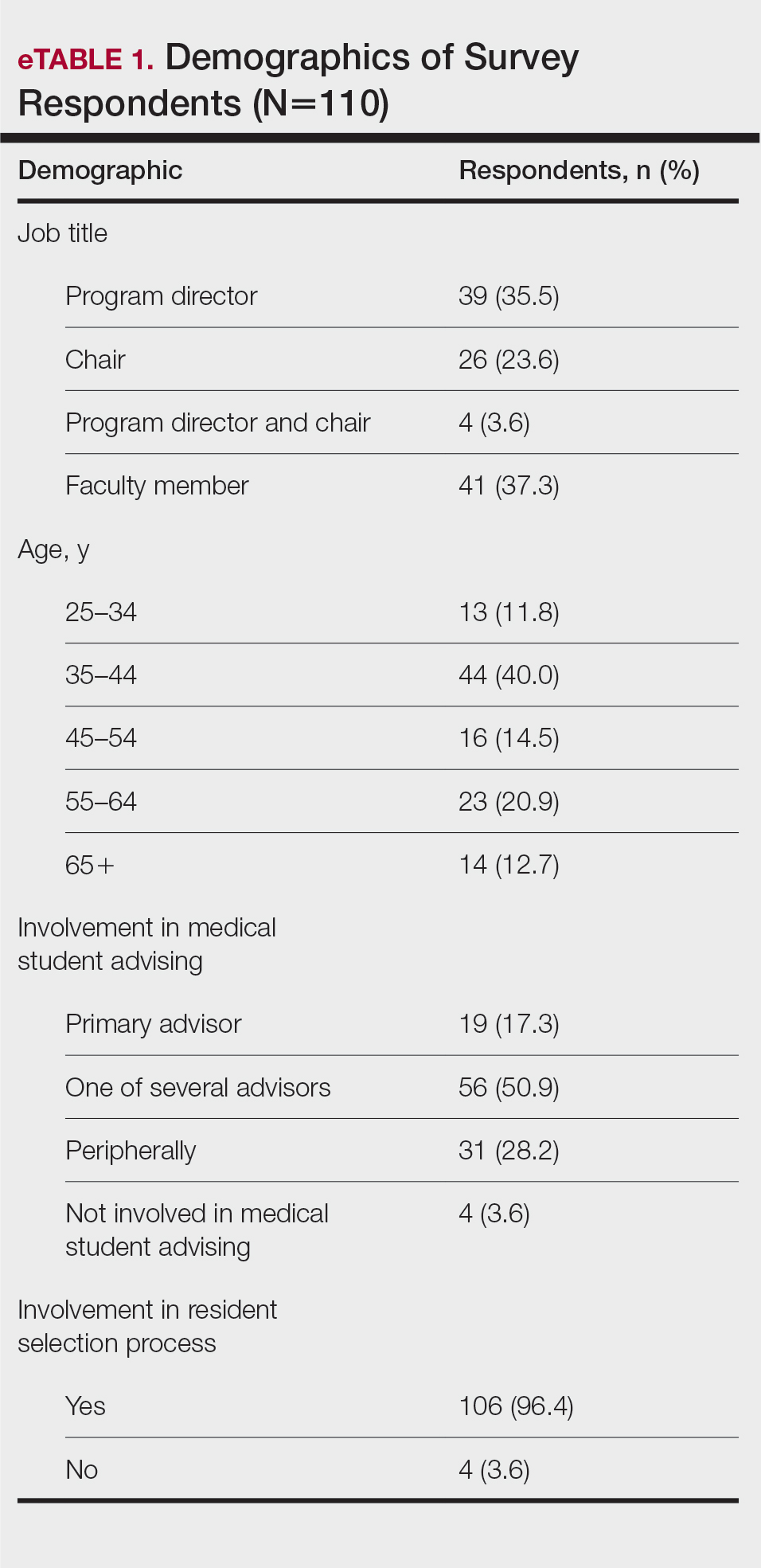

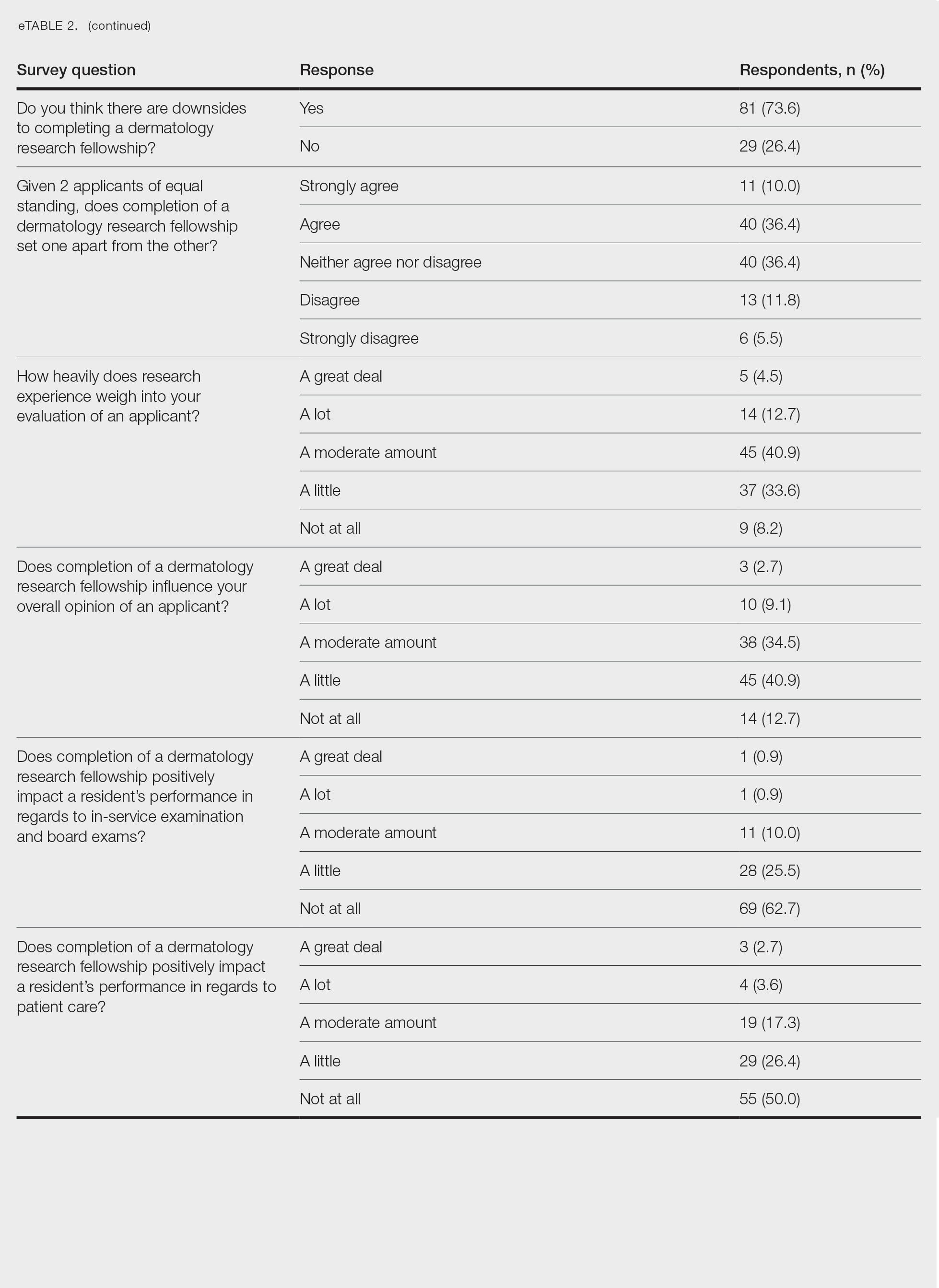

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

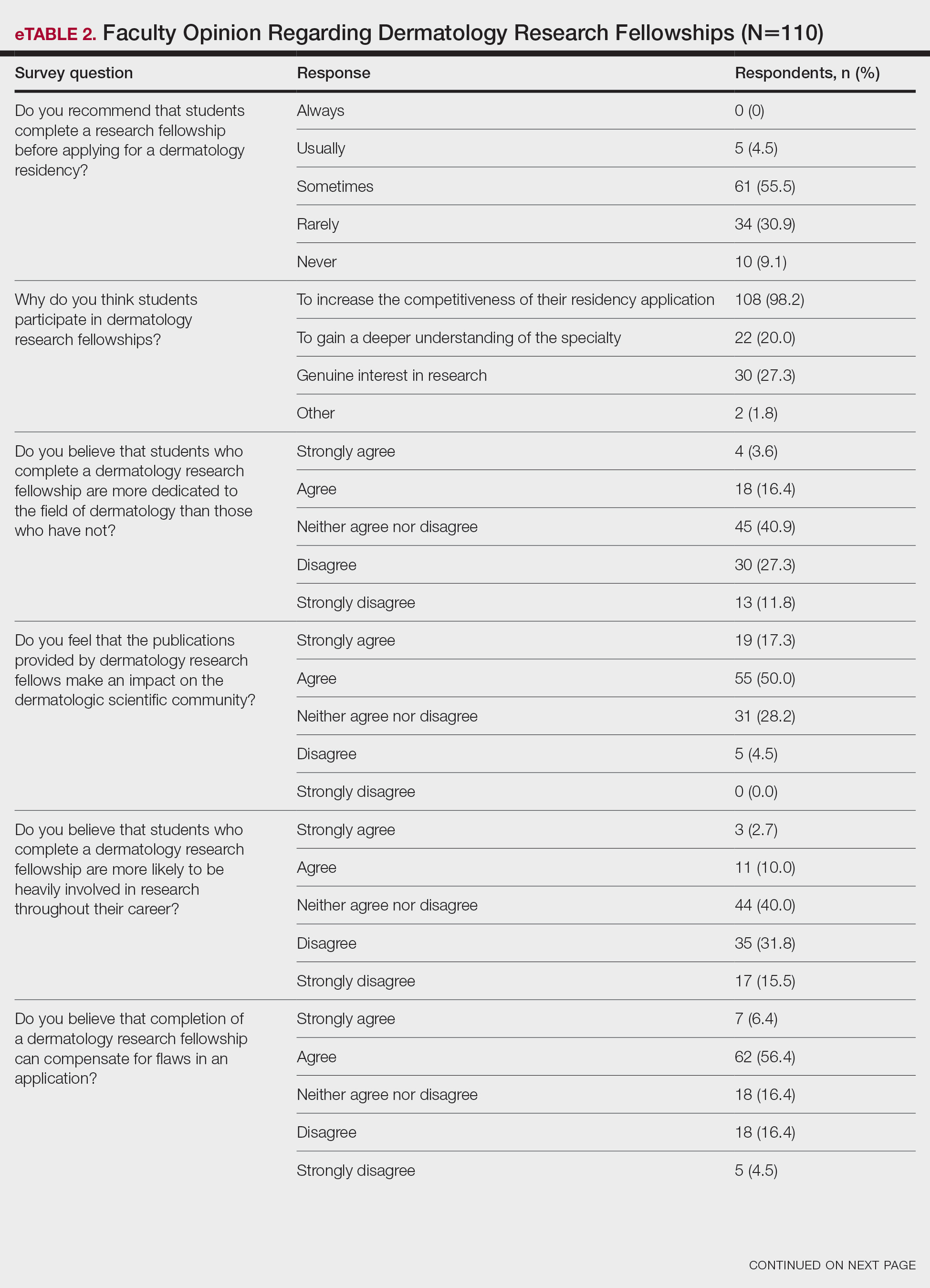

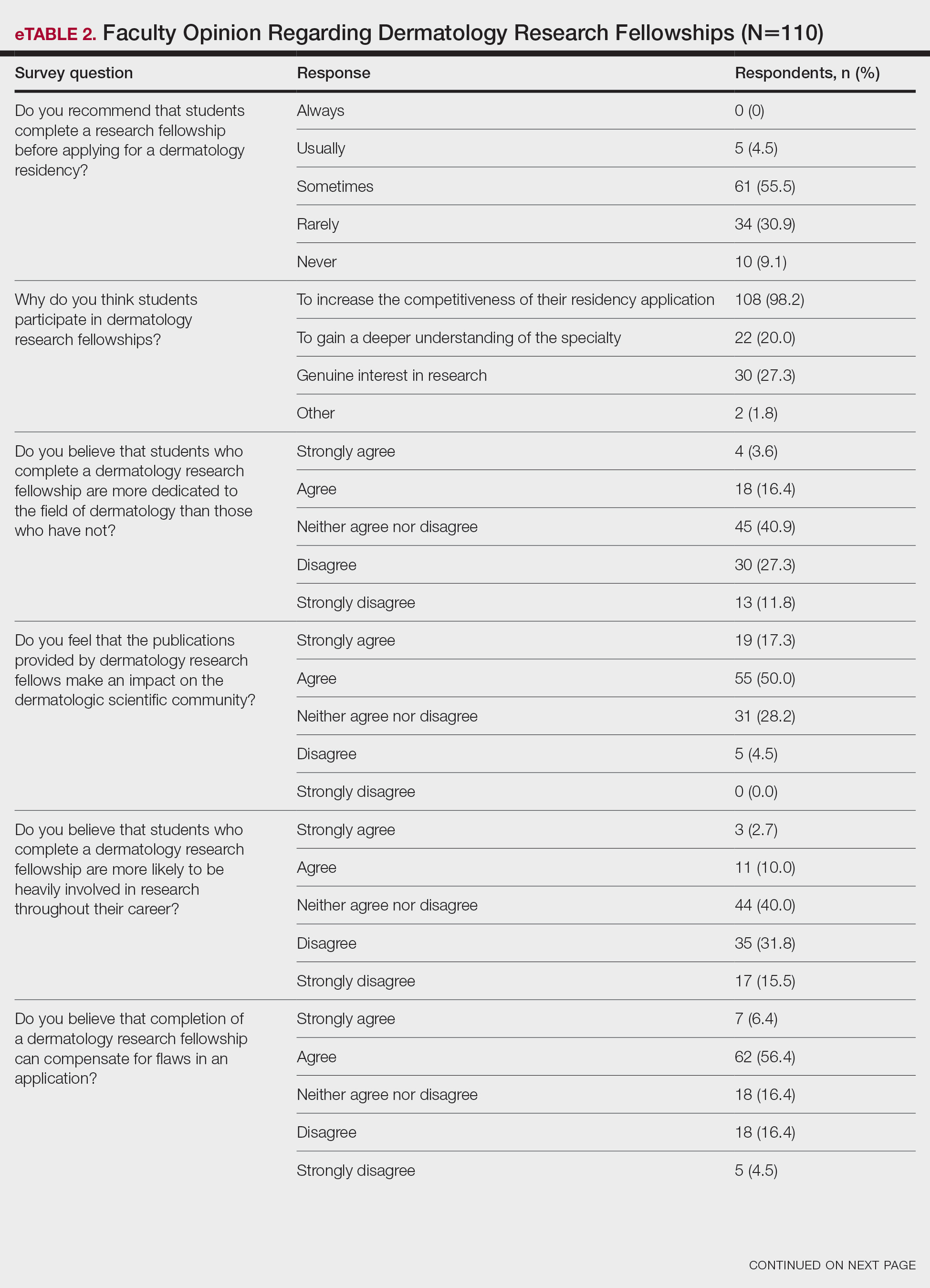

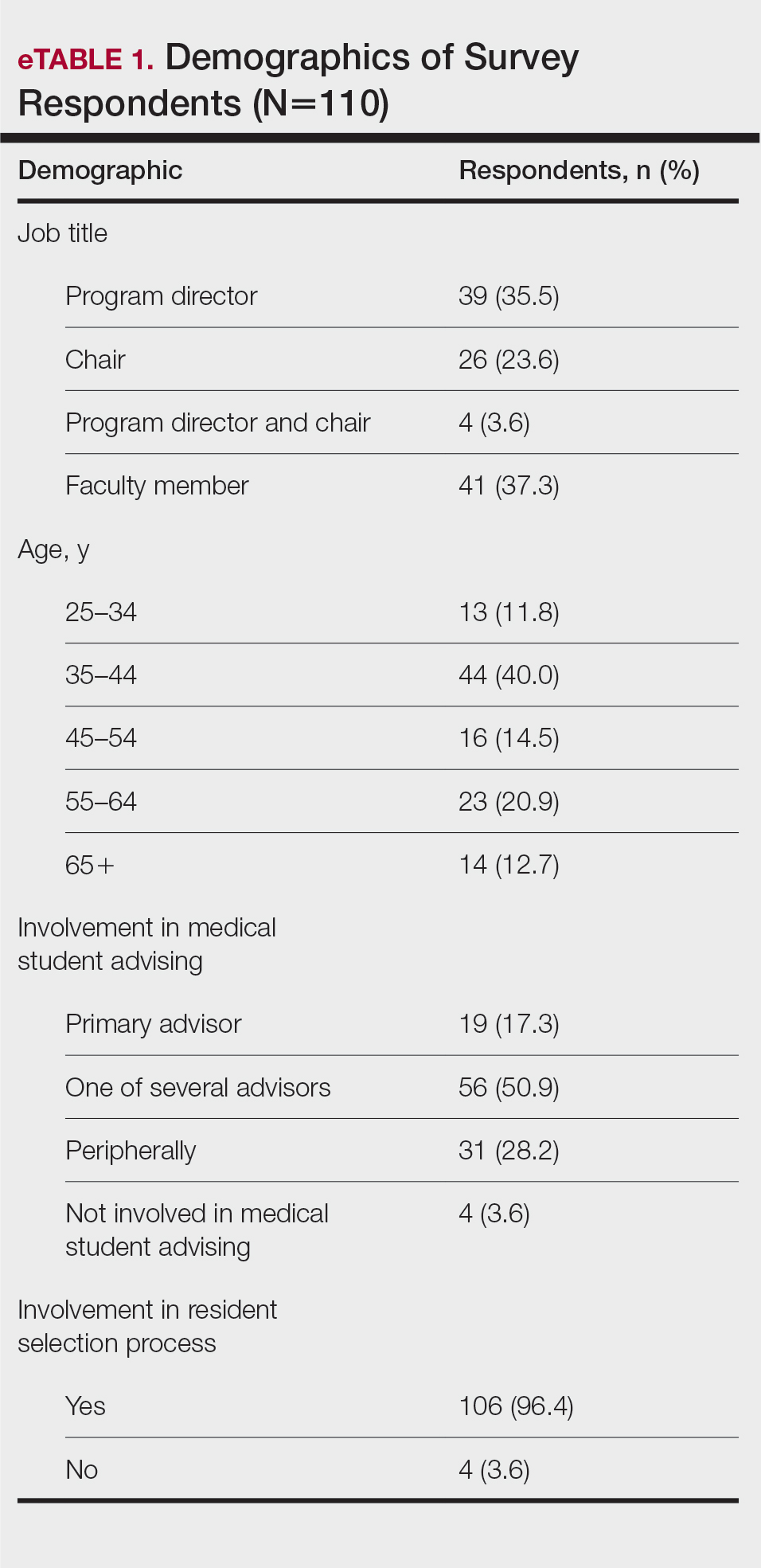

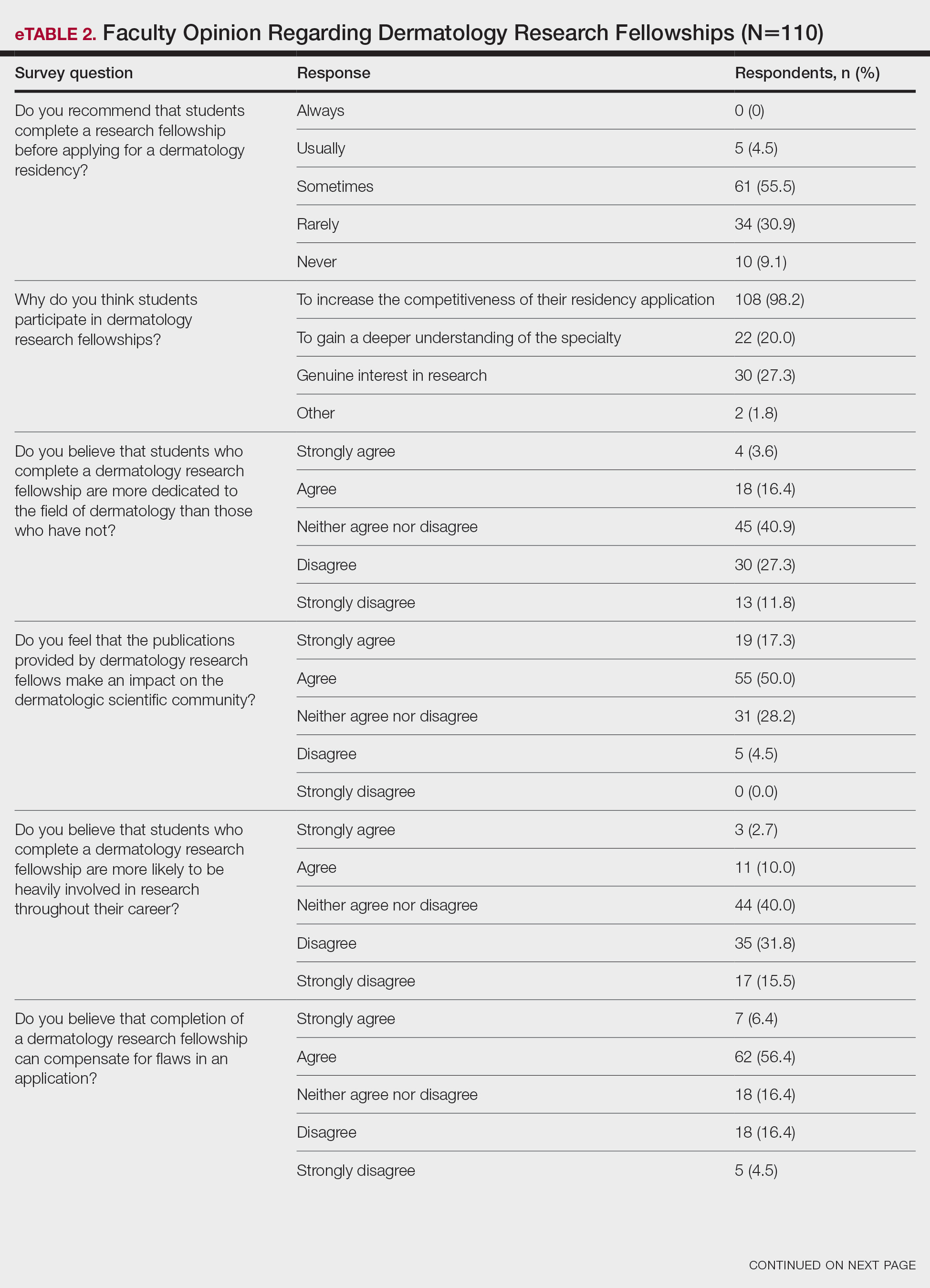

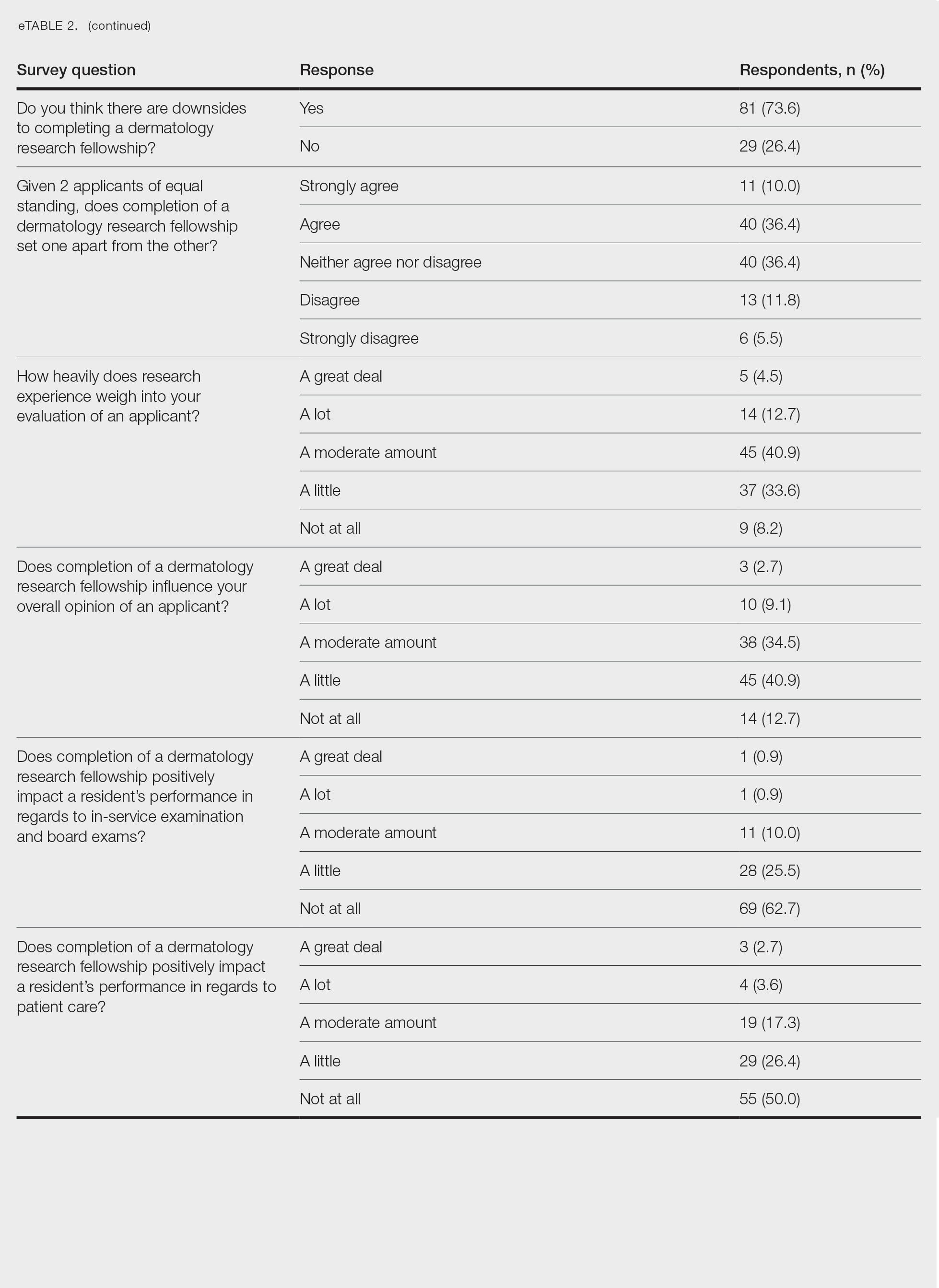

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Many medical students seeking to match into a dermatology residency program complete a research fellowship (RF).

- Completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants even though most advisors acknowledge that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their career, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

- The decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic and should be tailored to each individual applicant.

Purpuric Bullae on the Lower Extremities

The Diagnosis: Bullous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

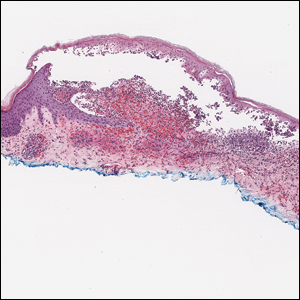

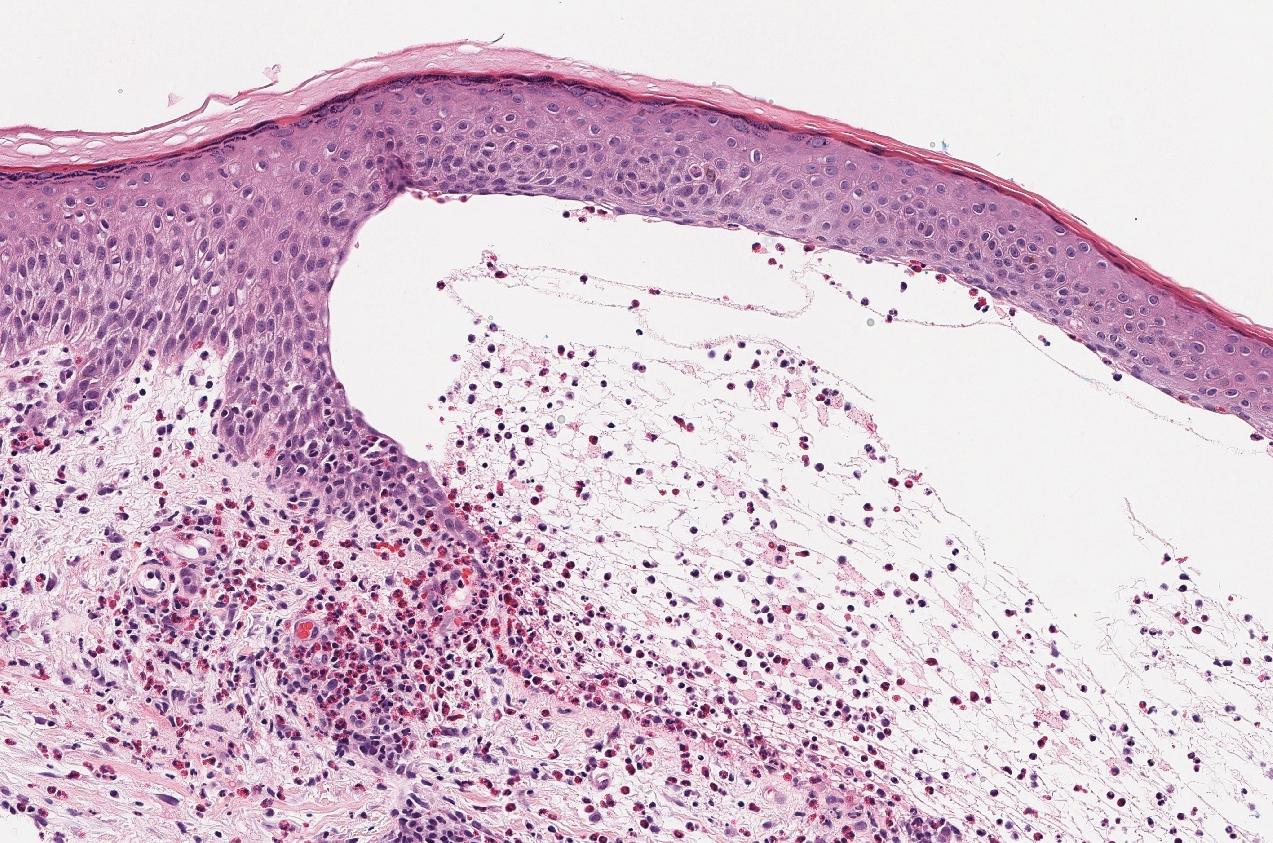

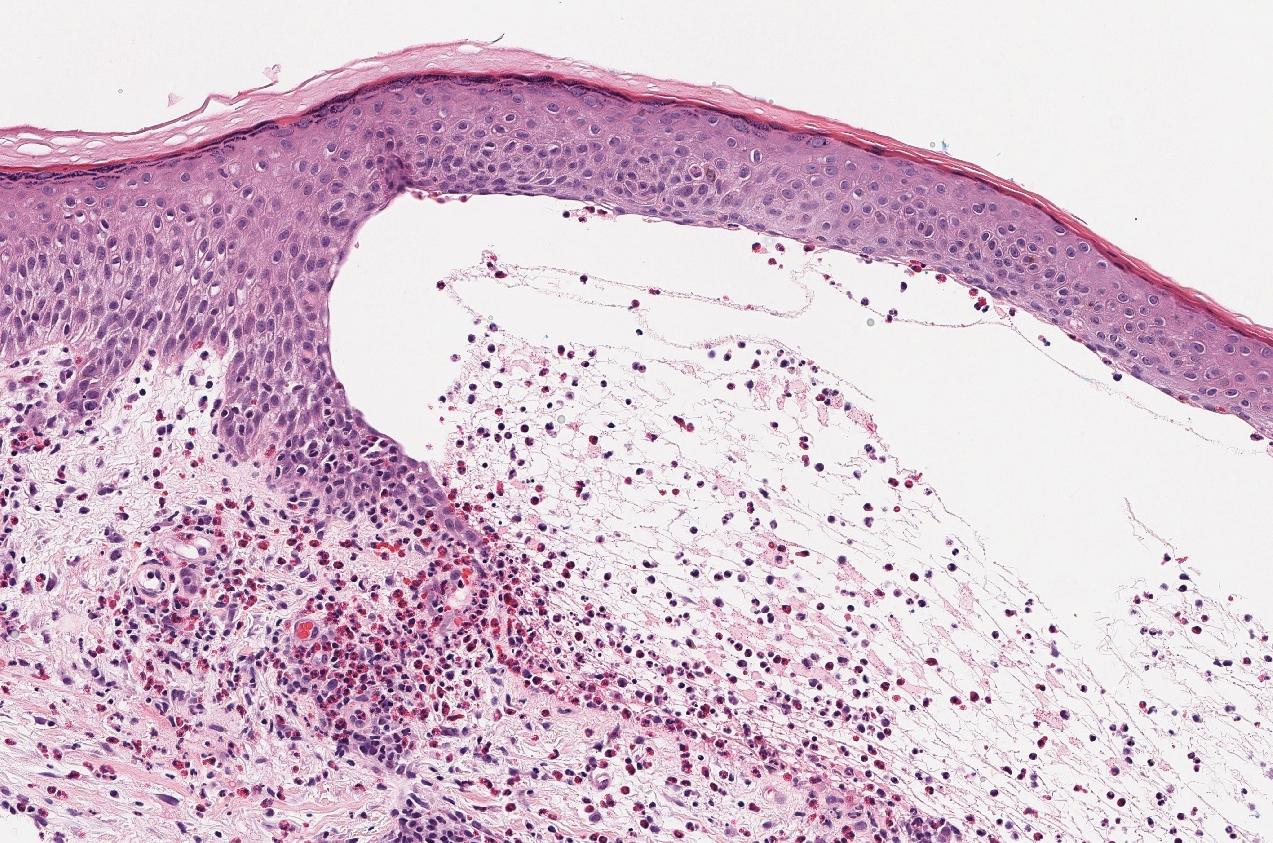

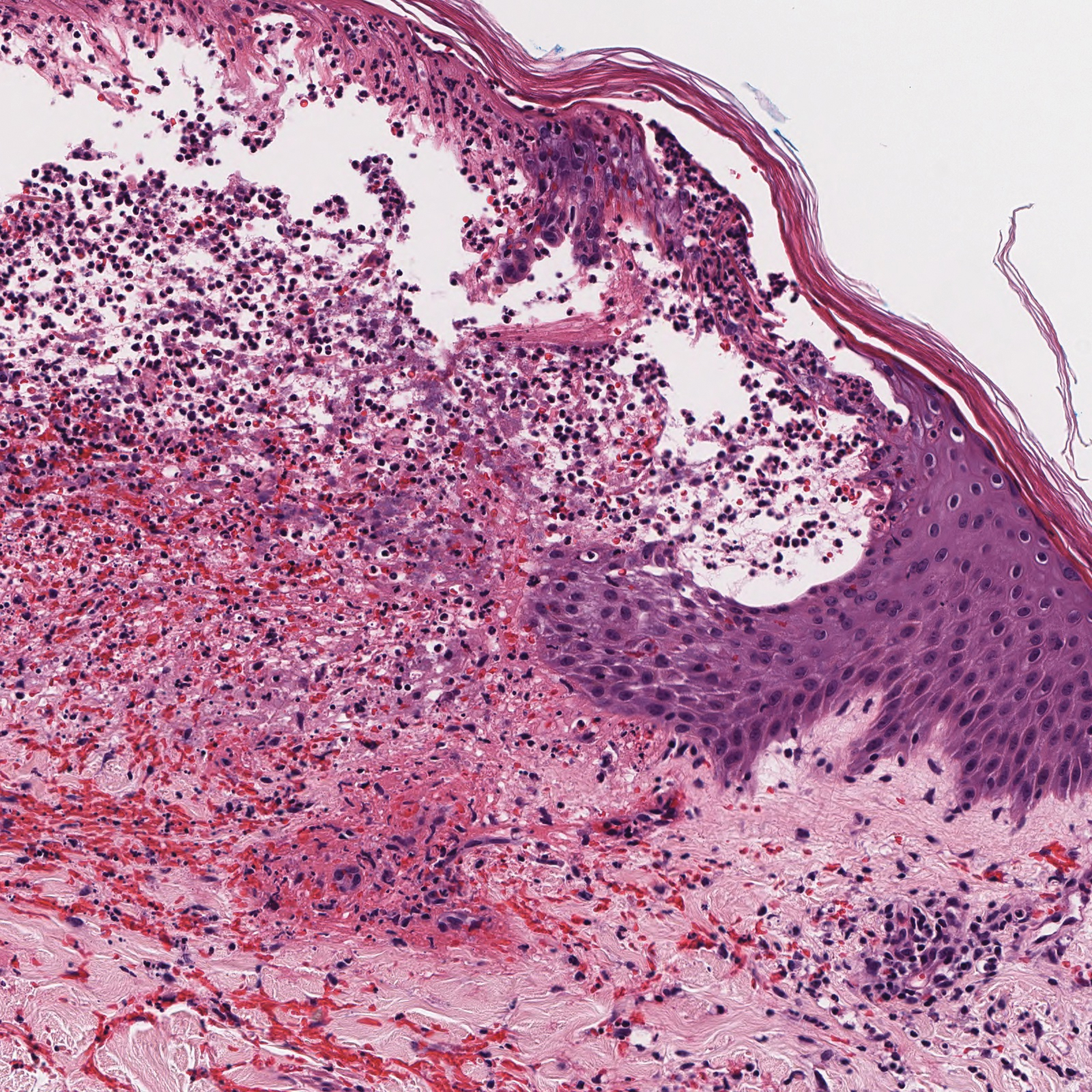

Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showed a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, karyorrhexis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrin deposition in the vessel wall (quiz images). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed fibrin surrounding the vasculature, consistent with vasculitis. The clinical and histopathological evaluation supported the diagnosis of bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). The patient had a full LCV workup including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and C3/C4/total complement level, which were all within reference range. The patient denied that she had taken any medications prior to the onset of the rash. She was started on a 12-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg, and the rash resolved in 1 week.

Although the incidence of LCV is estimated to be 30 cases per million individuals per year,1 bullous LCV is a rarer entity with only a few cases reported in the literature.2,3 As in our patient's case, up to 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic or the etiology cannot be determined despite laboratory workup and medication review. Other cases can be secondary to medication, infection, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy.3 Despite the exact pathogenesis of bullous LCV being unknown,4 it likely is related to a type III hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in postcapillary venules leading to endothelial injury, activation of the complement cascade, and development of intraepidermal or subepidermal blister formation depending on location of inflammation and edema.2 Clinically, an intraepidermal split would be more flaccid, similar to pemphigus vulgaris, while a subepidermal split, as in our patient, would be taut bullae. The subepidermal split more commonly is seen in bullous LCV.2

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis on H&E staining characteristically has a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, neutrophilic fragments called leukocytoclasis, and blood extravasation.3 Extravasated blood presents clinically as petechiae. In this case, the petechiae helped distinguish this entity from the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, DIF would be helpful in distinguishing bullous diseases such as bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris from LCV.2 Direct immunofluorescence in bullous LCV would have fibrinogen surrounding the vasculature without C3 and IgG deposition (intraepidermal or subepidermal).

Mild cases of LCV often resolve with supportive measures including elevation of the legs, ice packs applied to the affected area, and removal of the inciting drug or event.4 In the few cases reported in the literature, bullous LCV presented more diffusely than classic LCV with bullous lesions on the forearms and the lower extremities. Oral steroids are efficacious for extensive bullous LCV.4

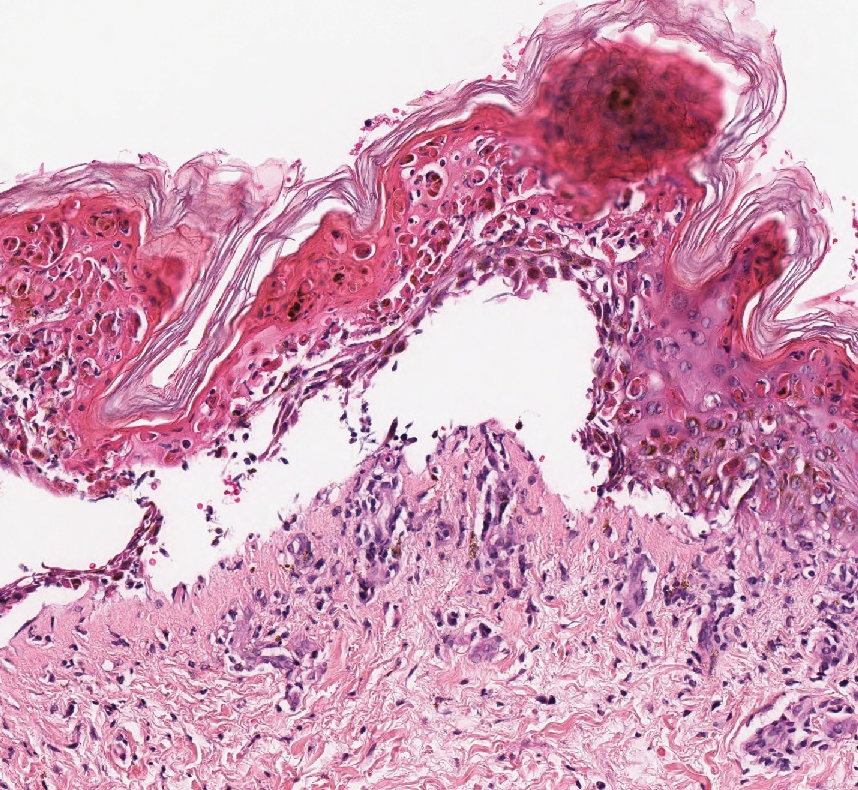

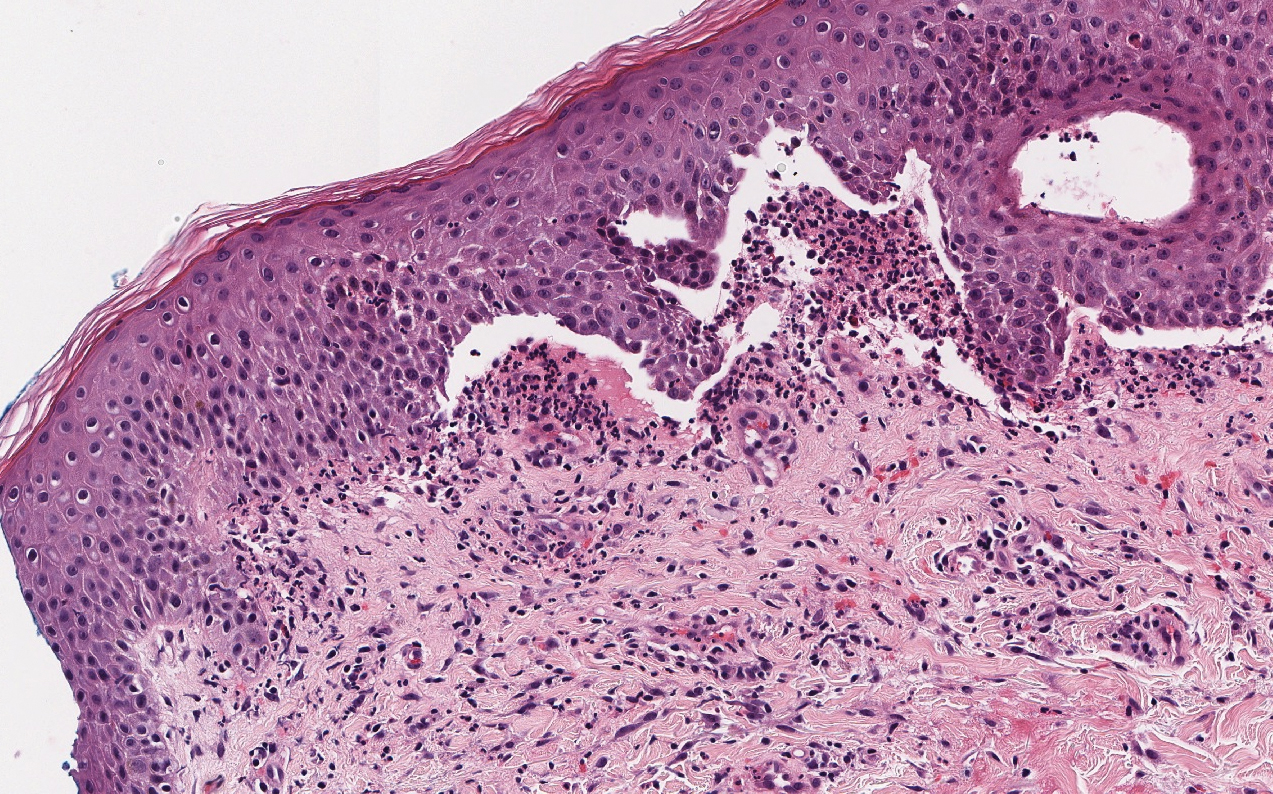

The differential diagnosis of bullous LCV includes bullous diseases with subepidermal split including BP and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease typically affecting patients older than 60 years.5 The pathogenesis of BP is related to development of autoantibodies directed against hemidesmosome components, bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG) 1 or BPAG2.5 Bullous pemphigoid presents clinically as widespread, generally pruritic, erythematous, urticarial plaques with bullae. Histologically, BP characteristically has a subepidermal split with superficial dermal edema and eosinophils at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence confirms the diagnosis with IgG and C3 deposition in an n-serrated pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.6 Bullous pemphigoid can be distinguished from bullous LCV by the older age of presentation, DIF findings, and the absence of purpura.

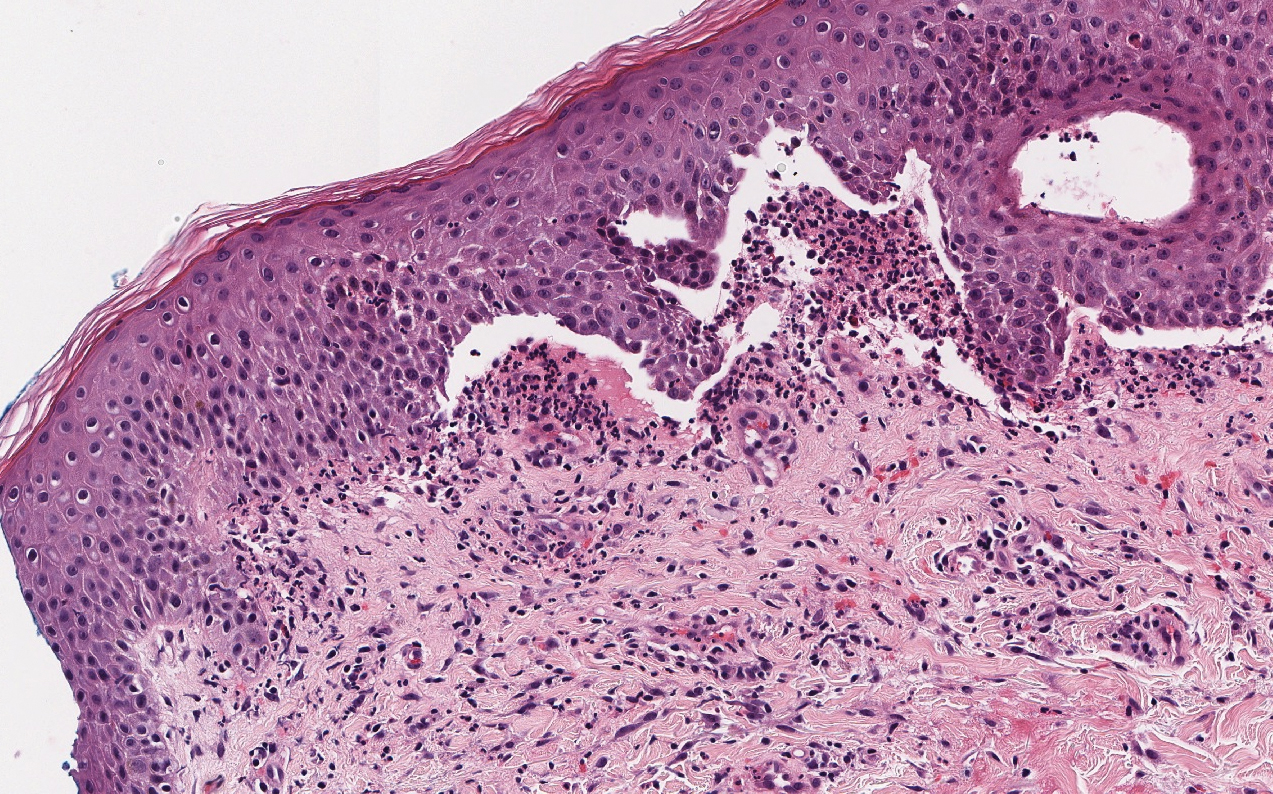

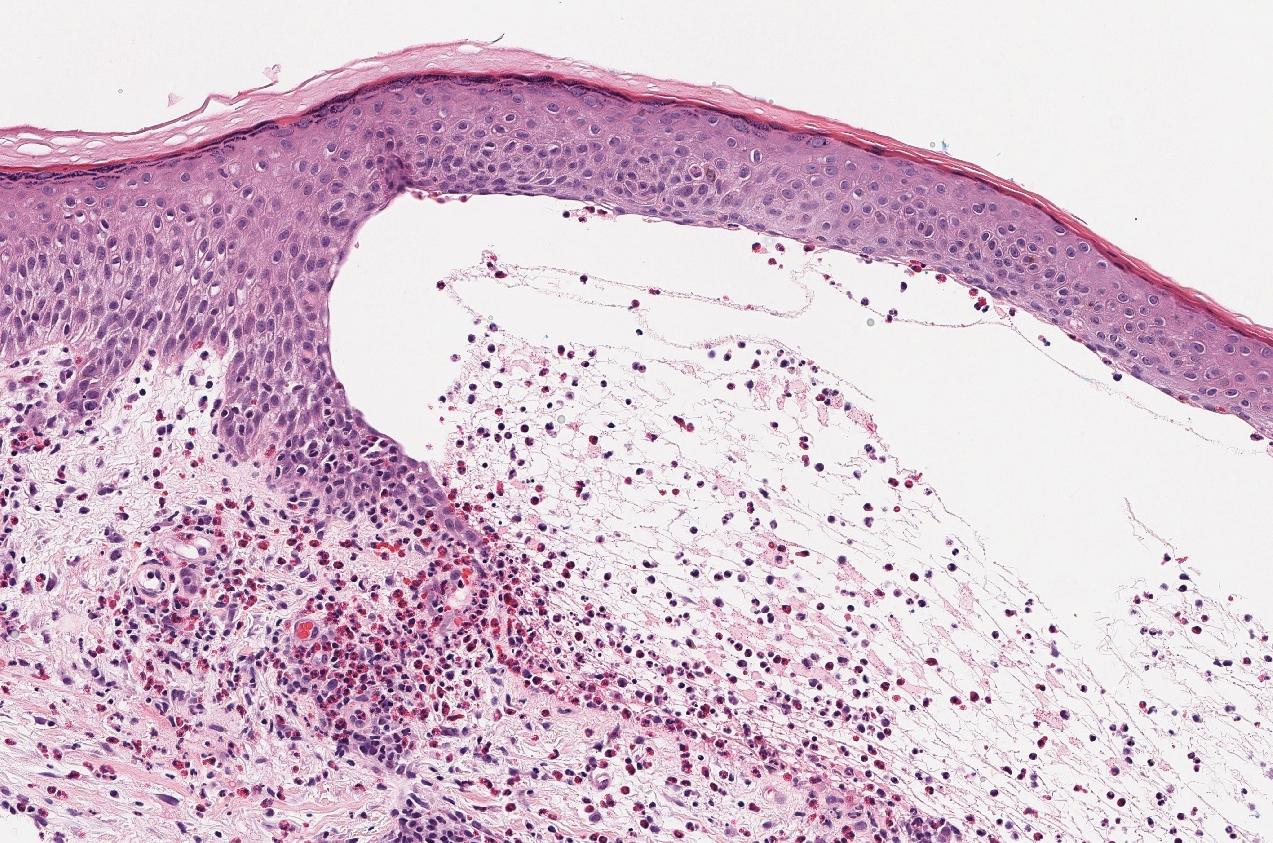

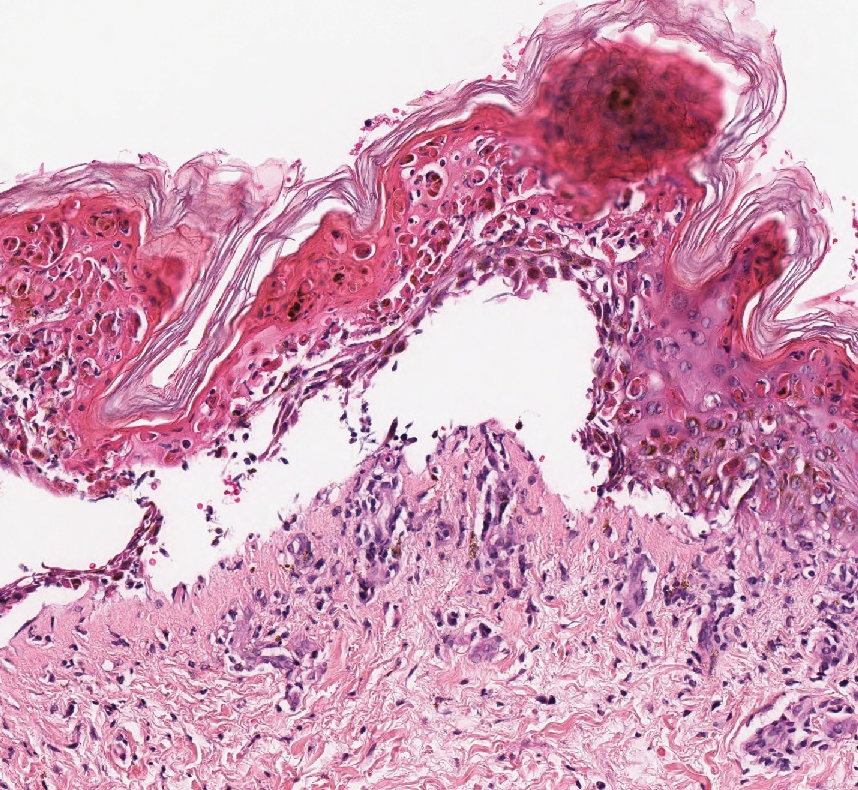

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis represents a rare subepidermal vesiculobullous disease occurring in patients in their 60s.7 Clinically, this entity presents as tense bullae often located on the periphery of an urticarial plaque, classically called the "string of pearls sign." Histologically, LABD also presents with subepidermal split; however, neutrophils are the predominant cell type vs eosinophils in BP (Figure 2).7 Direct immunofluorescence is specific with a linear deposition of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis most commonly is induced by vancomycin. Unlike bullous LCV, the bullae of LABD have an annular peripheral pattern on an erythematous base and lack purpura.

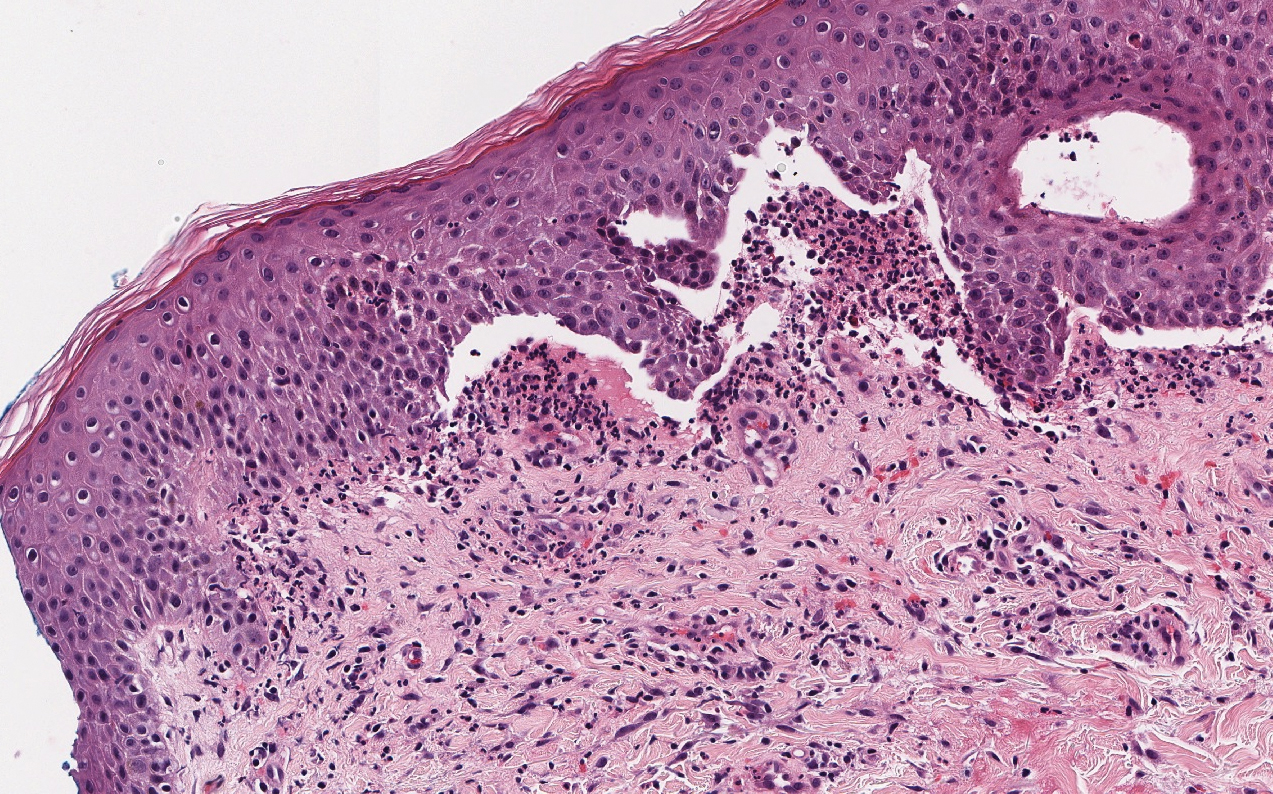

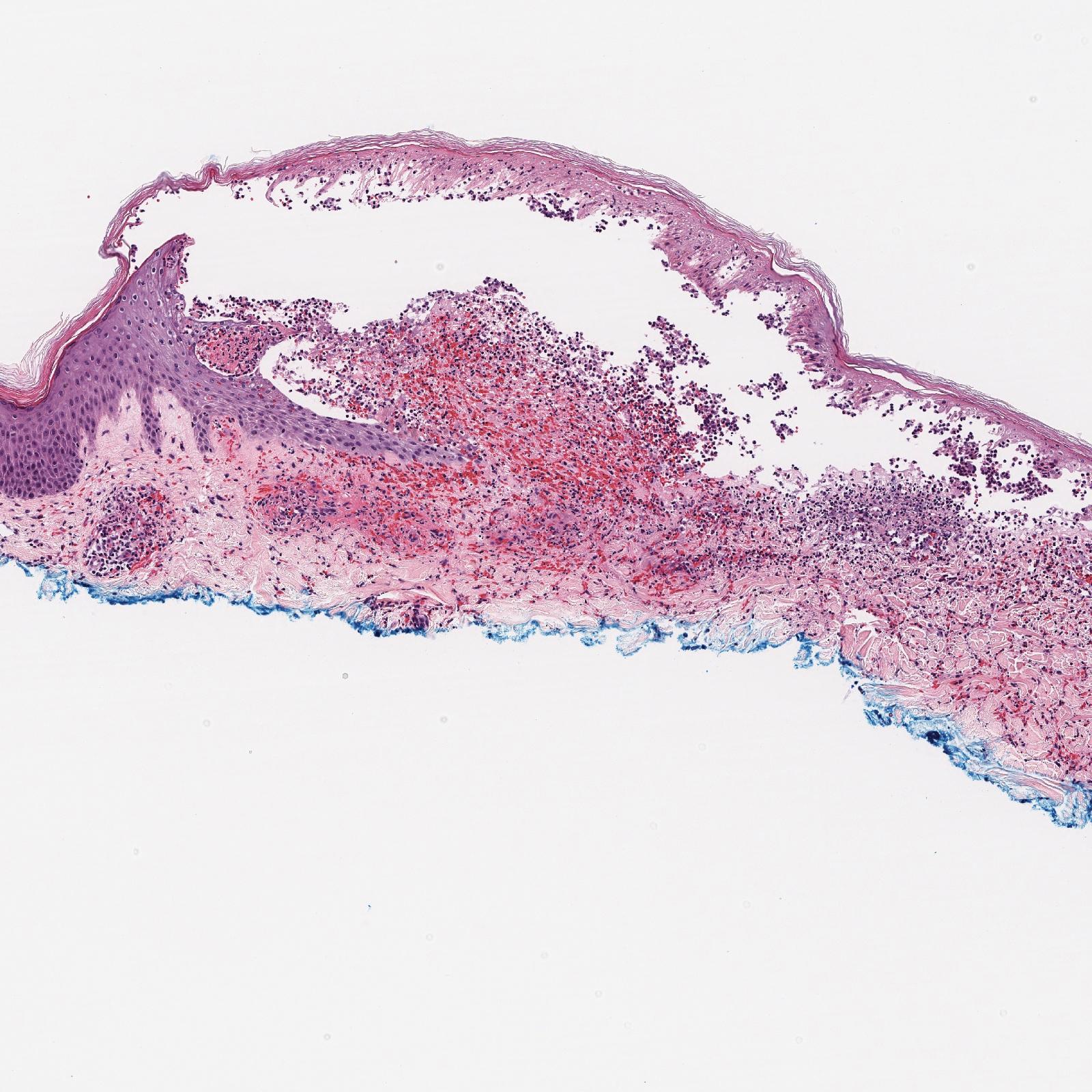

Stasis dermatitis is inflammation of the dermis due to venous insufficiency that often is present in the bilateral lower extremities. The disorder affects approximately 7% of adults older than 50 years, but it also can occur in younger patients.8 The pathophysiology of stasis dermatitis is caused by edema, which leads to extracellular fluid, plasma proteins, macrophages, and erythrocytes passing into the interstitial space. Patients with stasis dermatitis present with scaly erythematous papules and plaques or edematous blisters on the lower extremities. Diagnosis usually can be made clinically; however, a skin biopsy also can be helpful. Hematoxylin and eosin shows a pauci-inflammatory subepidermal bulla with fibrin (Figure 3).8 The overlying epidermis is intact. The dermis has cannon ball angiomatosis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrosis typical of stasis dermatitis. Stasis dermatitis with bullae is cell poor and lacks the perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and neutrophilic fragments that often are present in LCV, making the 2 entities distinguishable.

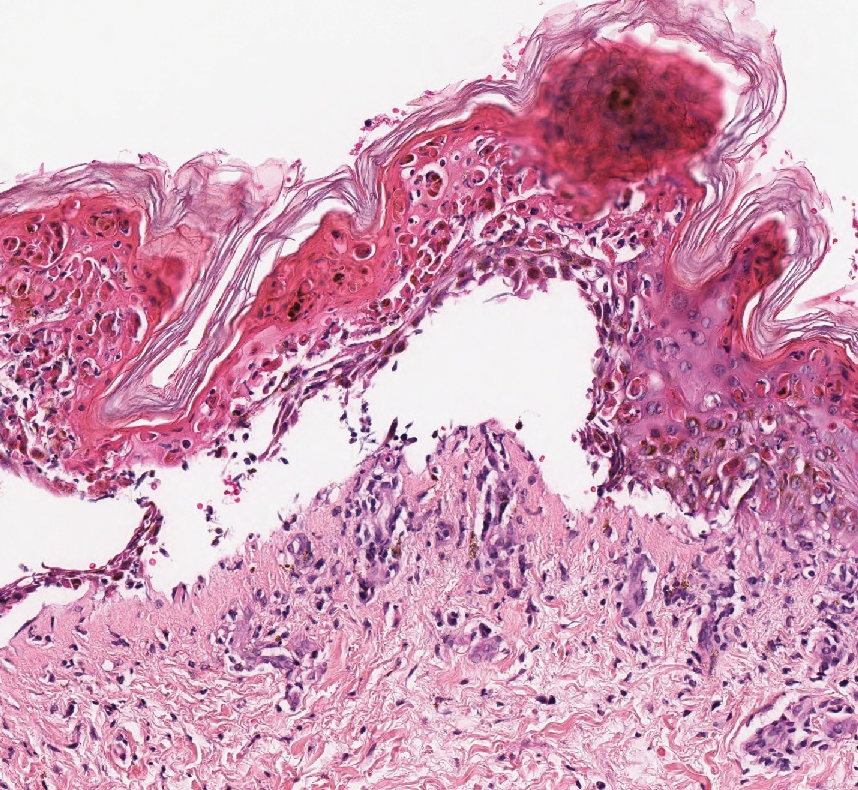

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) lies on a spectrum of severe cutaneous drug reactions involving the skin and mucous membranes. Cutaneous involvement typically begins on the trunk and face and later can involve the palms and soles.9 Similar drugs have been implicated in bullous LCV and SJS/TEN, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Histologically, SJS/TEN has full-thickness epidermal necrolysis, vacuolar interface, and keratinocyte apoptosis (Figure 4).9 The clinical presentation of sloughing of skin with positive Nikolsky sign, oral involvement, and H&E and DIF findings can help differentiate this entity from bullous LCV.

- Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19:77-78.

- Davidson KA, Ringpfeil F, Lee JB. Ibuprofen-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2001;67:303-307.

- Lazic T, Fonder M, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Orlistat-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2013;91:148-149.

- Mericliler M, Shnawa A, Al-Qaysi D, et al. Oxacillin-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. IDCases. 2019;17:E00539.

- Bernard P, Antonicelli F. Bullous pemphigoid: a review of its diagnosis, associations and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:513-528.

- High WA. Blistering disorders. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:161-171.

- Visentainer L, Massuda JY, Cintra ML, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD)--an atypical presentation. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1091-1093.

- Hyman DA, Cohen PR. Stasis dermatitis as a complication of recurrent levofloxacin-associated bilateral leg edema. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20399.

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showed a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, karyorrhexis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrin deposition in the vessel wall (quiz images). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed fibrin surrounding the vasculature, consistent with vasculitis. The clinical and histopathological evaluation supported the diagnosis of bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). The patient had a full LCV workup including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and C3/C4/total complement level, which were all within reference range. The patient denied that she had taken any medications prior to the onset of the rash. She was started on a 12-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg, and the rash resolved in 1 week.

Although the incidence of LCV is estimated to be 30 cases per million individuals per year,1 bullous LCV is a rarer entity with only a few cases reported in the literature.2,3 As in our patient's case, up to 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic or the etiology cannot be determined despite laboratory workup and medication review. Other cases can be secondary to medication, infection, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy.3 Despite the exact pathogenesis of bullous LCV being unknown,4 it likely is related to a type III hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in postcapillary venules leading to endothelial injury, activation of the complement cascade, and development of intraepidermal or subepidermal blister formation depending on location of inflammation and edema.2 Clinically, an intraepidermal split would be more flaccid, similar to pemphigus vulgaris, while a subepidermal split, as in our patient, would be taut bullae. The subepidermal split more commonly is seen in bullous LCV.2

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis on H&E staining characteristically has a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, neutrophilic fragments called leukocytoclasis, and blood extravasation.3 Extravasated blood presents clinically as petechiae. In this case, the petechiae helped distinguish this entity from the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, DIF would be helpful in distinguishing bullous diseases such as bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris from LCV.2 Direct immunofluorescence in bullous LCV would have fibrinogen surrounding the vasculature without C3 and IgG deposition (intraepidermal or subepidermal).

Mild cases of LCV often resolve with supportive measures including elevation of the legs, ice packs applied to the affected area, and removal of the inciting drug or event.4 In the few cases reported in the literature, bullous LCV presented more diffusely than classic LCV with bullous lesions on the forearms and the lower extremities. Oral steroids are efficacious for extensive bullous LCV.4

The differential diagnosis of bullous LCV includes bullous diseases with subepidermal split including BP and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease typically affecting patients older than 60 years.5 The pathogenesis of BP is related to development of autoantibodies directed against hemidesmosome components, bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG) 1 or BPAG2.5 Bullous pemphigoid presents clinically as widespread, generally pruritic, erythematous, urticarial plaques with bullae. Histologically, BP characteristically has a subepidermal split with superficial dermal edema and eosinophils at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence confirms the diagnosis with IgG and C3 deposition in an n-serrated pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.6 Bullous pemphigoid can be distinguished from bullous LCV by the older age of presentation, DIF findings, and the absence of purpura.

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis represents a rare subepidermal vesiculobullous disease occurring in patients in their 60s.7 Clinically, this entity presents as tense bullae often located on the periphery of an urticarial plaque, classically called the "string of pearls sign." Histologically, LABD also presents with subepidermal split; however, neutrophils are the predominant cell type vs eosinophils in BP (Figure 2).7 Direct immunofluorescence is specific with a linear deposition of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis most commonly is induced by vancomycin. Unlike bullous LCV, the bullae of LABD have an annular peripheral pattern on an erythematous base and lack purpura.

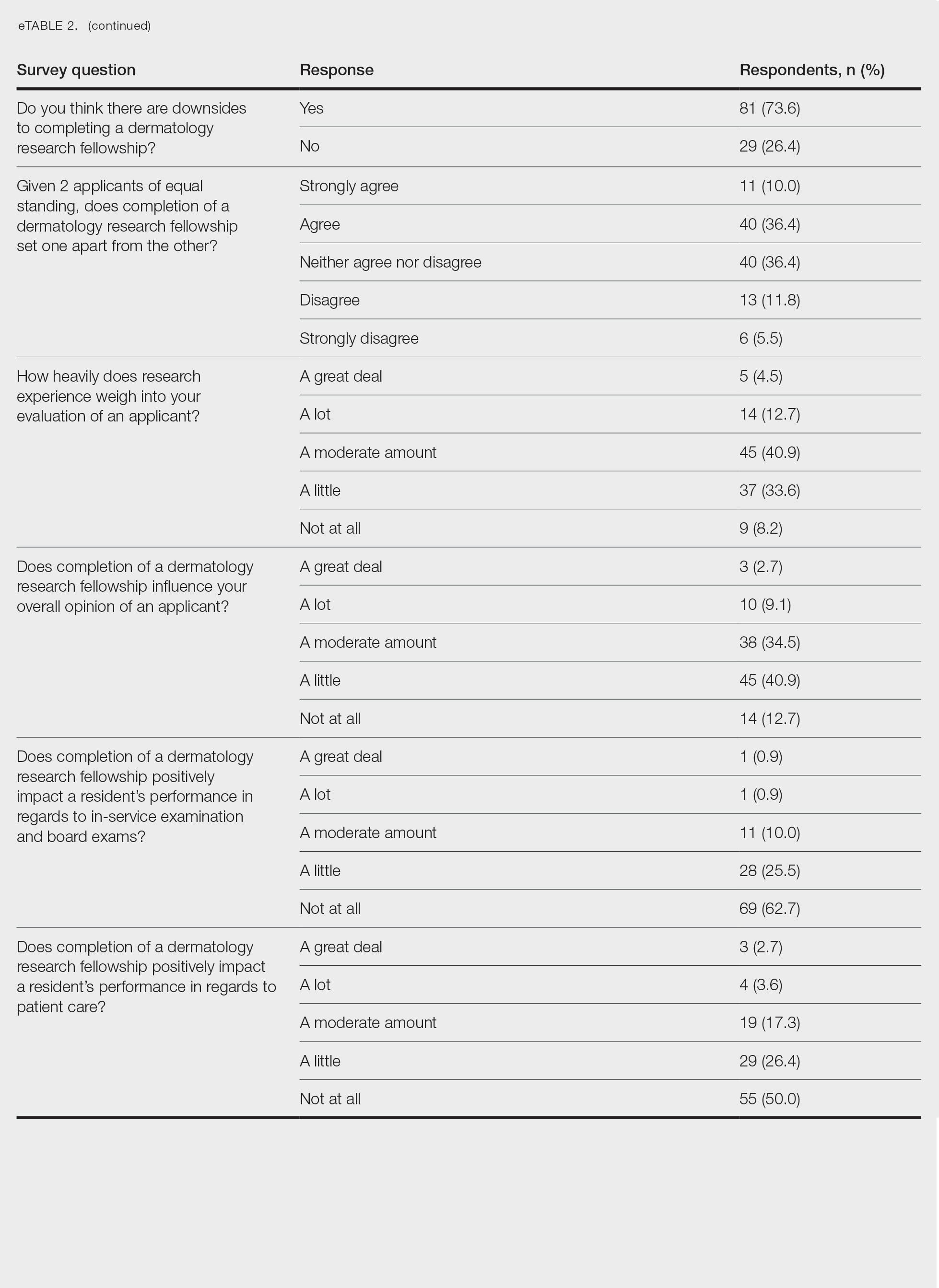

Stasis dermatitis is inflammation of the dermis due to venous insufficiency that often is present in the bilateral lower extremities. The disorder affects approximately 7% of adults older than 50 years, but it also can occur in younger patients.8 The pathophysiology of stasis dermatitis is caused by edema, which leads to extracellular fluid, plasma proteins, macrophages, and erythrocytes passing into the interstitial space. Patients with stasis dermatitis present with scaly erythematous papules and plaques or edematous blisters on the lower extremities. Diagnosis usually can be made clinically; however, a skin biopsy also can be helpful. Hematoxylin and eosin shows a pauci-inflammatory subepidermal bulla with fibrin (Figure 3).8 The overlying epidermis is intact. The dermis has cannon ball angiomatosis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrosis typical of stasis dermatitis. Stasis dermatitis with bullae is cell poor and lacks the perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and neutrophilic fragments that often are present in LCV, making the 2 entities distinguishable.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) lies on a spectrum of severe cutaneous drug reactions involving the skin and mucous membranes. Cutaneous involvement typically begins on the trunk and face and later can involve the palms and soles.9 Similar drugs have been implicated in bullous LCV and SJS/TEN, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Histologically, SJS/TEN has full-thickness epidermal necrolysis, vacuolar interface, and keratinocyte apoptosis (Figure 4).9 The clinical presentation of sloughing of skin with positive Nikolsky sign, oral involvement, and H&E and DIF findings can help differentiate this entity from bullous LCV.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showed a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, karyorrhexis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrin deposition in the vessel wall (quiz images). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed fibrin surrounding the vasculature, consistent with vasculitis. The clinical and histopathological evaluation supported the diagnosis of bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). The patient had a full LCV workup including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and C3/C4/total complement level, which were all within reference range. The patient denied that she had taken any medications prior to the onset of the rash. She was started on a 12-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg, and the rash resolved in 1 week.

Although the incidence of LCV is estimated to be 30 cases per million individuals per year,1 bullous LCV is a rarer entity with only a few cases reported in the literature.2,3 As in our patient's case, up to 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic or the etiology cannot be determined despite laboratory workup and medication review. Other cases can be secondary to medication, infection, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy.3 Despite the exact pathogenesis of bullous LCV being unknown,4 it likely is related to a type III hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in postcapillary venules leading to endothelial injury, activation of the complement cascade, and development of intraepidermal or subepidermal blister formation depending on location of inflammation and edema.2 Clinically, an intraepidermal split would be more flaccid, similar to pemphigus vulgaris, while a subepidermal split, as in our patient, would be taut bullae. The subepidermal split more commonly is seen in bullous LCV.2

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis on H&E staining characteristically has a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, neutrophilic fragments called leukocytoclasis, and blood extravasation.3 Extravasated blood presents clinically as petechiae. In this case, the petechiae helped distinguish this entity from the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, DIF would be helpful in distinguishing bullous diseases such as bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris from LCV.2 Direct immunofluorescence in bullous LCV would have fibrinogen surrounding the vasculature without C3 and IgG deposition (intraepidermal or subepidermal).

Mild cases of LCV often resolve with supportive measures including elevation of the legs, ice packs applied to the affected area, and removal of the inciting drug or event.4 In the few cases reported in the literature, bullous LCV presented more diffusely than classic LCV with bullous lesions on the forearms and the lower extremities. Oral steroids are efficacious for extensive bullous LCV.4

The differential diagnosis of bullous LCV includes bullous diseases with subepidermal split including BP and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease typically affecting patients older than 60 years.5 The pathogenesis of BP is related to development of autoantibodies directed against hemidesmosome components, bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG) 1 or BPAG2.5 Bullous pemphigoid presents clinically as widespread, generally pruritic, erythematous, urticarial plaques with bullae. Histologically, BP characteristically has a subepidermal split with superficial dermal edema and eosinophils at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence confirms the diagnosis with IgG and C3 deposition in an n-serrated pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.6 Bullous pemphigoid can be distinguished from bullous LCV by the older age of presentation, DIF findings, and the absence of purpura.

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis represents a rare subepidermal vesiculobullous disease occurring in patients in their 60s.7 Clinically, this entity presents as tense bullae often located on the periphery of an urticarial plaque, classically called the "string of pearls sign." Histologically, LABD also presents with subepidermal split; however, neutrophils are the predominant cell type vs eosinophils in BP (Figure 2).7 Direct immunofluorescence is specific with a linear deposition of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis most commonly is induced by vancomycin. Unlike bullous LCV, the bullae of LABD have an annular peripheral pattern on an erythematous base and lack purpura.

Stasis dermatitis is inflammation of the dermis due to venous insufficiency that often is present in the bilateral lower extremities. The disorder affects approximately 7% of adults older than 50 years, but it also can occur in younger patients.8 The pathophysiology of stasis dermatitis is caused by edema, which leads to extracellular fluid, plasma proteins, macrophages, and erythrocytes passing into the interstitial space. Patients with stasis dermatitis present with scaly erythematous papules and plaques or edematous blisters on the lower extremities. Diagnosis usually can be made clinically; however, a skin biopsy also can be helpful. Hematoxylin and eosin shows a pauci-inflammatory subepidermal bulla with fibrin (Figure 3).8 The overlying epidermis is intact. The dermis has cannon ball angiomatosis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrosis typical of stasis dermatitis. Stasis dermatitis with bullae is cell poor and lacks the perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and neutrophilic fragments that often are present in LCV, making the 2 entities distinguishable.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) lies on a spectrum of severe cutaneous drug reactions involving the skin and mucous membranes. Cutaneous involvement typically begins on the trunk and face and later can involve the palms and soles.9 Similar drugs have been implicated in bullous LCV and SJS/TEN, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Histologically, SJS/TEN has full-thickness epidermal necrolysis, vacuolar interface, and keratinocyte apoptosis (Figure 4).9 The clinical presentation of sloughing of skin with positive Nikolsky sign, oral involvement, and H&E and DIF findings can help differentiate this entity from bullous LCV.

- Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19:77-78.

- Davidson KA, Ringpfeil F, Lee JB. Ibuprofen-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2001;67:303-307.

- Lazic T, Fonder M, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Orlistat-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2013;91:148-149.

- Mericliler M, Shnawa A, Al-Qaysi D, et al. Oxacillin-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. IDCases. 2019;17:E00539.

- Bernard P, Antonicelli F. Bullous pemphigoid: a review of its diagnosis, associations and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:513-528.

- High WA. Blistering disorders. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:161-171.

- Visentainer L, Massuda JY, Cintra ML, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD)--an atypical presentation. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1091-1093.

- Hyman DA, Cohen PR. Stasis dermatitis as a complication of recurrent levofloxacin-associated bilateral leg edema. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20399.

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39.

- Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19:77-78.

- Davidson KA, Ringpfeil F, Lee JB. Ibuprofen-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2001;67:303-307.

- Lazic T, Fonder M, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Orlistat-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2013;91:148-149.

- Mericliler M, Shnawa A, Al-Qaysi D, et al. Oxacillin-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. IDCases. 2019;17:E00539.

- Bernard P, Antonicelli F. Bullous pemphigoid: a review of its diagnosis, associations and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:513-528.

- High WA. Blistering disorders. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:161-171.

- Visentainer L, Massuda JY, Cintra ML, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD)--an atypical presentation. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1091-1093.

- Hyman DA, Cohen PR. Stasis dermatitis as a complication of recurrent levofloxacin-associated bilateral leg edema. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20399.

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39.

A 30-year-old woman with a medical history of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus and morbid obesity presented to the dermatology clinic with a painful blistering rash on the lower extremities with scattered red-purple papules of 1 week's duration. The rash began on the left dorsal foot. Physical examination showed nonblanching, 2- to 4-mm, violaceous papules with numerous vesiculopustular bullae on the lower extremities from the dorsal feet to the proximal knee. A shave biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin stain and a punch biopsy for direct immunofluorescence were performed.