User login

Clinical Outcomes of Anatomical Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in a Young, Active Population

Although total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) has proved to be a reliable solution in older patients, treatment in younger patients with glenohumeral arthritis remains controversial, and there are still few reliable long-term surgical options.1-8 These options include abrasion arthroplasty and arthroscopic management,9,10 biologic glenoid resurfacing,11,12 and humeral hemiarthroplasty with13 or without14,15 glenoid treatment and anatomical TSA.

In the younger cohort, 20-year TSA survivorship rates up to 84% have been reported, and unsatisfactory subjective outcomes have been unacceptably high.16 In addition, there is a paucity of literature addressing the impact of TSA on return to sport. Recommendations on returning to an athletic life style are based largely on surveys of expert opinion17,18 and heterogeneous studies of either older patients (eg, age >50-55 years) who are active19-21 or younger patients with no defined level of activity.5,7,8,16,22-24

To our knowledge, no one has evaluated the short-term morbidity and clinical outcomes within a young, high-demand patient population, such as the US military. Therefore, we conducted a study to evaluate the clinical success and complications of TSA performed for glenohumeral arthritis in a young, active population. We hypothesized that patients who had undergone TSA would have a low rate of return to duty, an increased rate of component failure, and a higher reoperation rate because of increased upper extremity demands.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining protocol approval from the William Beaumont Army Medical Center Institutional Review Board, we searched the Military Health System (MHS) Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (M2) database to retrospectively review the cases of all tri-service US military service members who had undergone primary anatomical TSA (Current Procedural Terminology code 23472) between January 1, 2007 and June 31, 2014. This was a multisurgeon, multicenter study. Patient exclusion criteria were nonmilitary or retired status at time of surgery; primary surgery consisting of limited glenohumeral resurfacing procedure, hemiarthroplasty, or reverse TSA; surgery for acute proximal humerus fracture; rotator cuff deficiency diagnosed before or during surgery; and insufficient follow-up (eg, <12 months, unless medically separated beforehand).

The M2 database is an established tool that has been used for clinical outcomes research on treatment of a variety of orthopedic conditions.25,26 The Medical Data Repository, which is operated by MHS, is populated by its military healthcare providers. The MHS, which offers worldwide coverage for all beneficiaries either at Department of Defense facilities or purchased using civilian providers, is among the largest known closed healthcare systems.

All active-duty US military service members are uniformly required to adhere to stringent and regularly evaluated physical fitness standards, which typically exceed those of average civilians. Routine physical training is required in the form of aerobic fitness, weight training, tactical field exercises, and core military tasks, such as the ability to march at least 2 miles while carrying heavy fighting loads. In addition to satisfying required height and weight standards, all service members are subject to semiannual service-specific physical fitness evaluations inclusive of timed push-ups, sit-ups, and an aerobic event. Service members may also be required to maintain a level of physical training above these baseline standards, contingent on their branch of service, rank, and military occupational specialty. If a service member is unable to maintain these standards, medical separation may be initiated.

Demographic and occupational data were extracted from the database. These data included age, sex, military rank, and branch of service. Line-by-line analysis of the Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application (Version 22; 3M) electronic medical record was then performed to confirm the underlying diagnosis, surgical procedure, and surgery date. Further chart review yielded additional patient-based factors (eg, laterality, hand dominance, presence and type of prior shoulder surgeries) and surgical factors (eg, surgery indication, implant design). We evaluated clinical and functional outcomes as well as perioperative complications, including both major and minor systemic and local complications as previously described27,28; preoperative and postoperative range of motion (ROM) and self-reported pain score (SRPS, scale 1-10) as measured by physical therapist and surgeon at follow-up; secondary surgical interventions; timing of return to duty; and postoperative deployment history. The primary outcome measures were revision reoperation after index procedure, and military discharge for persistent shoulder-related disability. Clinical failure was defined as component failure or reoperation. Medical Evaluation Board (MEB) is a formal separation from the military in which it is deemed that a service member is no longer able to fulfill his or her duty because of a medical condition.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using statistical means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and/or SDs. Categorical data were reported as frequencies or percentages. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the correlation between possible risk factors and the primary outcome measures. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

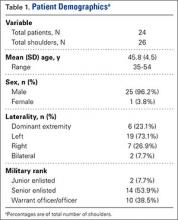

We identified 24 service members (26 shoulders) who had undergone anatomical TSA during the study period (Table 1). Mean (SD) age was 45.8 (4.5) years (range, 35-54 years), and the cohort was predominately male (25/26 shoulders; 96.2%). Most cohort members were of senior enlisted rank (14, 58.3%), and the US Army was the predominant branch of military service (13, 54.2%). The right side was the operative extremity in 7 cases (26.9%), and the dominant shoulder was involved in 6 cases (23.1%). Two patients (8.3%) underwent staged bilateral TSA. Most patients (76.9%) underwent TSA on the nondominant extremity.

Surgical Variables

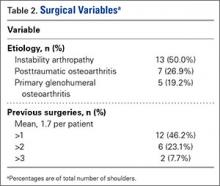

TSA was indicated for post-instability arthropathy in 13 cases (50.0%), posttraumatic osteoarthritis in 7 cases (26.9%), and unspecified glenohumeral arthritis, which includes primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis, in 5 cases (19.2%) (Table 2). One case was attributed to iatrogenically induced chondrolysis secondary to intra-articular lidocaine pump. Twelve patients (46.2%) had at least 1 previous surgery. Of the shoulders with instability, 10 (76.9%) had undergone a total of 14 surgical stabilization procedures—10 anterior labral repairs, 2 posterior labral repairs, and 2 capsular plications. The other shoulders had undergone a total of 18 procedures, which included 4 rotator cuff repairs and 3 cartilage restoration procedures.

Clinical Outcomes

Mean (SD) follow-up was 41.0 (21.3) months (range, 11.6-97.6 months). All but 1 shoulder (96.2%) had follow-up of 12 months or more (the only patient with shorter follow-up was because of MEB), and 76.9% of patients had follow-up of 24 months or more (4 of the 6 patients with follow-up under 24 months were medically separated) (Table 3). In all cases, mean ROM improved with respect to flexion, abduction, and external rotation. At final follow-up, mean (SD) ROM was 138° (36°) forward flexion (range, 60°-180°), 125° (39°) abduction (range, 45°-180°), 48° (19°) external rotation at 0° abduction (range, 20°-90°), and 80° (9.4°) external rotation at 90° abduction (range, 70°-90°). Preoperative flexion, abduction, and external rotation at 0° and 90° abduction were all improved at final follow-up. The most improvement in ROM occurred within 6 months after surgery.

Overall patient satisfaction with surgery was 92.3% (n = 24). Ultimately, 18 (72.0%) of 25 shoulders with follow-up of 1 year or more were able to return to active duty within 1 year after surgery, though only 10 (45.5%) of 22 with follow-up of 2 years or more remained active 2 years after surgery. Furthermore, 5 patients (20.8%) were deployed after surgery, and all were still on active duty at final follow-up. By final follow-up, 9 (37.5%) of 24 service members were unable to return to military function; 7 had been medically discharged from the military for persistent shoulder disability, and 2 were in the process of being medically discharged.

In all cases, SRPS improved from before surgery (5.2 out of 10) to final follow-up (1.4). At final follow-up, 22 patients (88.0%) reported mild pain (0-3), and no one had pain above 6.

Complications

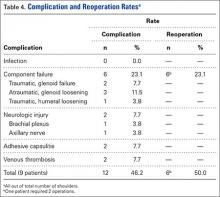

Nine patients had a total of 12 postoperative complications (46.2%): 6 component failures (23.1%), 2 neurologic injuries (7.7%; 1 permanent axillary nerve injury, 1 transient brachial plexus neuritis), 2 cases of adhesive capsulitis (7.7%), and 2 episodes of venous thrombosis (7.7%; 1 superficial, 1 deep) (Table 4). There were no documented infections. Six reoperations (23.1%) were performed for the 6 component failures (2 traumatic dislocations of prosthesis resulting in acute glenoid component failure, 3 cases of atraumatic glenoid loosening, 1 case of humeral stem loosening after periprosthetic fracture). Atraumatic glenoid component loosening occurred a mean (SD) of 40.6 (14.2) months after surgery (range, 20.8-54.2 months).

Surgical Failures

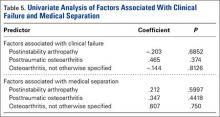

Eight service members underwent MEB. Six patients experienced component failure. Factors contributing to both clinical failure and separation from active duty by means of MEB were evaluated with univariate analysis (Table 5). No statistically significant risk factors, including surgical revision and presence of perioperative complications, were identified.

Discussion

We confirmed that our cohort of young service members (mean age, 45.8 years), who had undergone TSA for glenohumeral arthritis, had a relatively higher rate of component failure (23.1%) and a higher reoperation rate (23.1%) with low rates of return to military duty at short-term to midterm follow-up. Our results parallel those of a limited series with a younger cohort (Table 6).7,16,19,21,23,24 The high demand and increased life expectancy of the younger patients with glenohumeral arthritis potentiates the risk of complications, component loosening, and ultimate failure.29 To our knowledge, the present article is the first to report clinical and functional outcomes and perioperative risk profiles in a homogenously young, active military cohort after TSA.

The mean age of our study population (46 years) is one of the lowest in the literature. TSA in younger patients (age, <50-55 years) and older, active patients (>55 years) has received increased attention as a result of the expanding indications and growing popularity of TSA in these groups. Other studies have upheld the efficacy of TSA in achieving predictable pain relief and functional improvement in a diverse and predominantly elderly population.15,30-34 Alternative treatments, including humeral head resurfacing15,30,35 and soft-tissue interposition,15,36-40 have also shown inferior short- and long-term results in terms of longevity and degree of clinical or functional improvement.31-34,41 In addition, the ream-and-run technique has had promising early results by improving glenohumeral kinematics, pain relief, and shoulder function.13,42,43 However, although implantation of a glenoid component is avoided in young, active people because of reduced longevity and higher rates of component failure, the trade-offs are inadequately treated glenoid disease, suboptimal pain relief, and progression of glenoid arthritis eventually requiring revision. Furthermore, midterm and long-term survivorship of TSA in general is unknown, and there remain few good options for treating end-stage arthritis in young, active patients.

Our cohort had high rates of complications (46.2%) and revisions (23.1%). Two in 5 patients had postoperative complications, most commonly component failure resulting in reoperation. In the literature, complication rates among young patients who underwent TSA are much lower (4.8%-10.9%).16,23,24 Our cohort’s most common complication was component failure (23.1%), which was most often attributed to atraumatic, aseptic glenoid component loosening and required reoperation. Previously reported revision rates in a young population that underwent TSA (0%-11%)16,23,24 were also significantly lower than those in the present analysis (23.1%), underscoring the impact of operative indications, postoperative activity levels, and occupational demands on ultimate failure rates. Interestingly, all revisions in our study were for component failure, whereas previous reports have described a higher rate for infection.22 However, the same studies also found glenoid lucency rates as high as 76% at 10-year follow-up.16 Furthermore, in a review of 136 TSAs with unsatisfactory outcomes, glenoid loosening was the most common reason for presenting to clinic after surgery.44 Specifically, our population had a high rate of glenohumeral arthritis secondary to instability (50.0%) and posttraumatic osteoarthritis (26.9%). For many reasons, outcomes were worse in younger patients with a history of glenohumeral instability33 than in older patients without a high incidence of instability.45 This young cohort with higher demands may have had accelerated polyethylene wear patterns caused by repetitive overhead activity, which may have arisen because of a higher functional profile after surgery and greater patient expectations after arthroplasty. In addition, patients with a history of instability may have altered glenohumeral anatomy, especially with previous arthroscopic or open stabilization procedures. Anatomical changes include excessive posterior glenoid wear, internal rotation contracture, patulous capsular tissue, static or dynamic posterior humeral subluxation, and possible overconstraint after prior stabilization procedures. Almost half of our population had a previous surgery; our patients averaged 1.7 previous surgeries each.

Although estimates of component survivorship at a high-volume civilian tertiary-referral center were as high as 97% at 10 years and 84% at 20 years,7,16 10-year survivorship in patients with a history of instability was only 61%.3 TSA survivorship in our young, active cohort is already foreseeably dramatically reduced, given the 23.1% revision rate at 28.5-month follow-up. This consideration must be addressed during preoperative counseling with the young patient with glenohumeral arthritis and a history of shoulder instability.

Despite the high rates of complications and revisions in our study, 92.3% of patients were satisfied with surgery, 88.0% experienced minimal persistence of pain (mean 3.8-point decrease on SRPS), and 100% maintained improved ROM at final follow-up. Satisfaction in the young population has varied significantly, from 52% to 95%, generally on the basis of physical activity.16,22-24 The reasonable rate of postoperative satisfaction in the present analysis is comparable to what has been reported in patients of a similar age (Table 6).7,16,22 However, despite high satisfaction and pain relief, patients were inconsistently able to return to the upper limits of physical activity required of active-duty military service. In addition, we cannot exclude secondary gain motivations for pursuing medical retirement, similar to that seen in patients receiving worker’s compensation.

Other authors have conversely found more favorable functional outcomes and survivorship rates.23,24 In a retrospective review of 46 TSAs in patients 55 years or younger, Bartelt and colleagues24 found sustained improvements in pain, ROM, and satisfaction at 7-year follow-up.24 Raiss and colleagues23 conducted a prospective study of TSA outcomes in 21 patients with a mean age of 55 years and a mean follow-up of 7 years and reported no revisions and only 1 minor complication, a transient brachial plexus palsy.23 The discrepancy between these studies may reflect different activity levels and underlying pathology between cohorts. The present population is unique in that it represents a particularly difficult confluence of factors for shoulder arthroplasty surgeons. The high activity, significant overhead and lifting occupational demands, and discordant patient expectations of this military cohort place a significant functional burden on the implants, the glenoid component in particular. Furthermore, this patient group has a higher incidence of more complex glenohumeral pathology resulting in instability, posttraumatic, or capsulorrhaphy arthropathy, and multiple prior arthroscopic and open stabilization procedures.

At final follow-up, only 33% of our patients were still on activity duty, 37.5% had completed or were completing medical separation from the military after surgery for persistent shoulder disability, and 37.5% were retired from the military. Five patients (20.8%) deployed after surgery. This young, active cohort of service members who had TSA for glenohumeral arthritis faced a unique set of tremendous physical demands. A retrospective case series investigated return to sport in 100 consecutive patients (mean age, 68.9 years) who were participating in recreational and competitive athletics and underwent unilateral TSA.21 The patients were engaged most commonly in swimming (20.4%), golf (16.3%), cycling (16.3%), and fitness training (16.3%). The authors found that, at a mean follow-up of 2.8 years, 49 patients (89%) were able to continue in sports, though 36.7% thought their sport activity was restricted after TSA. In another retrospective case series (61 TSAs), McCarty and colleagues19 found that 48 patients (71%) were improved in their sports participation, and 50% increased their frequency of participation after surgery.

There are no specific recommendations on returning to military service or high-level sport after surgery. Recommendations on returning to sport after TSA have been based largely on small case series involving specific sports46,47 and surveys of expert opinion.17,18 In a survey on postoperative physical activity in young patients after TSA conducted by Healy and colleagues,17 35 American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons members recommended avoiding contact and impact sports while permitting return to nonimpact sports, such as swimming, which may still impart significant stress to the glenohumeral joint. In an international survey of 101 shoulder and elbow surgeons, Magnussen and colleagues18 also found that most recommended avoiding a return to impact sports that require intensive upper extremity demands and permitting full return to sports at preoperative levels. This likely is a result of the perception that most of these patients having TSA are older and have less rigorous involvement in sports at the outset and a lower propensity for adverse patient outcomes. However, these recommendations may place a younger, more high-demand patient at significantly greater risk. The active-duty cohort engages in daily physical training, including push-ups and frequent overhead lifting, which could account for the high failure rates and low incidence of postoperative deployment. Although TSA seems to demonstrate good initial results in terms of return to high-demand activities, the return-to-duty profile in our study highlights the potential pitfalls of TSA in active individuals attempting to return to high-demand preoperative function.

Our analysis was limited by the fact that we used a small patient cohort, contributing to underpowered analysis of the potential risk factors predictive of reoperation and medical discharge. Although our minimum follow-up was 12 months, with the exception of 1 patient who was medically separated at 11.6 months because of shoulder disability, we captured 5 patients (19.2%) who underwent medical separation but who would otherwise be excluded. Therefore, this limitation is not major in that, with a longer minimum follow-up, we would be excluding a significant number of patients with such persistent disability after TSA that they would not be able to return to duty at anywhere near their previous level. In this retrospective study, we were additionally limited to analysis of the data in the medical records and could not control for variables such as surgeon technique, implant choice, and experience. Complete radiographic images were not available, limiting analysis of radiographic outcomes. Given the lack of a standardized preoperative imaging protocol, we could not evaluate glenoid version on axial imaging. It is possible that some patients with early aseptic glenoid loosening had posterior subluxation or a Walch B2 glenoid, which has a higher failure rate.48 The strengths of this study include its unique analysis of a homogeneous young, active, high-risk patient cohort within a closed healthcare system. In the military, these patients are subject to intense daily physical and occupational demands. In addition, the clinical and functional outcomes we studied are patient-centered and therefore relevant during preoperative counseling. Further investigations might focus on validated outcome measures and on midterm to long-term TSA outcomes in an active military population vis-à-vis other alternatives for clinical management.

Conclusion

By a mean follow-up of 3.5 years, only a third of the service members had returned to active duty, roughly a third had retired, and more than a third had been medically discharged because of persistent disability attributable to the shoulder. Despite initial improvements in ROM and pain, midterm outcomes were poor. The short-term complication rate (46.2%) and the rate of reoperation for component failure (23.1%) should be emphasized during preoperative counseling.

1. Tokish JM. The mature athlete’s shoulder. Sports Health. 2014;6(1):31-35.

2. Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of glenoid arthrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(6):860-867.

3. Sperling JW, Antuna SA, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck C, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty for arthritis after instability surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(10):1775-1781.

4. Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, et al; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(6):375-382.

5. Johnson MH, Paxton ES, Green A. Shoulder arthroplasty options in young (<50 years old) patients: review of current concepts. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(2):317-325.

6. Cole BJ, Yanke A, Provencher MT. Nonarthroplasty alternatives for the treatment of glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5 suppl):S231-S240.

7. Denard PJ, Raiss P, Sowa B, Walch G. Mid- to long-term follow-up of total shoulder arthroplasty using a keeled glenoid in young adults with primary glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):894-900.

8. Denard PJ, Wirth MA, Orfaly RM. Management of glenohumeral arthritis in the young adult. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(9):885-892.

9. Millett PJ, Horan MP, Pennock AT, Rios D. Comprehensive arthroscopic management (CAM) procedure: clinical results of a joint-preserving arthroscopic treatment for young, active patients with advanced shoulder osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):440-448.

10 Millett PJ, Gaskill TR. Arthroscopic management of glenohumeral arthrosis: humeral osteoplasty, capsular release, and arthroscopic axillary nerve release as a joint-preserving approach. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(9):1296-1303.

11. Savoie FH 3rd, Brislin KJ, Argo D. Arthroscopic glenoid resurfacing as a surgical treatment for glenohumeral arthritis in the young patient: midterm results. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):864-871.

12. Strauss EJ, Verma NN, Salata MJ, et al. The high failure rate of biologic resurfacing of the glenoid in young patients with glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(3):409-419.

13. Matsen FA 3rd, Warme WJ, Jackins SE. Can the ream and run procedure improve glenohumeral relationships and function for shoulders with the arthritic triad? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2088-2096.

14. Lo IK, Litchfield RB, Griffin S, Faber K, Patterson SD, Kirkley A. Quality-of-life outcome following hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(10):2178-2185.

15. Wirth M, Tapscott RS, Southworth C, Rockwood CA Jr. Treatment of glenohumeral arthritis with a hemiarthroplasty: a minimum five-year follow-up outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(5):964-973.

16. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Minimum fifteen-year follow-up of Neer hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged fifty years or younger. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(6):604-613.

17. Healy WL, Iorio R, Lemos MJ. Athletic activity after joint replacement. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(3):377-388.

18. Magnussen RA, Mallon WJ, Willems WJ, Moorman CT 3rd. Long-term activity restrictions after shoulder arthroplasty: an international survey of experienced shoulder surgeons. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):281-289.

19. McCarty EC, Marx RG, Maerz D, Altchek D, Warren RF. Sports participation after shoulder replacement surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1577-1581.

20. Schmidt-Wiethoff R, Wolf P, Lehmann M, Habermeyer P. Physical activity after shoulder arthroplasty [in German]. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2002;16(1):26-30.

21. Schumann K, Flury MP, Schwyzer HK, Simmen BR, Drerup S, Goldhahn J. Sports activity after anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):2097-2105.

22. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(4):464-473.

23. Raiss P, Aldinger PR, Kasten P, Rickert M, Loew M. Total shoulder replacement in young and middle-aged patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(6):764-769.

24. Bartelt R, Sperling JW, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged fifty-five years or younger with osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):123-130.

25. Waterman BR, Burns TC, McCriskin B, Kilcoyne K, Cameron KL, Owens BD. Outcomes after Bankart repair in a military population: predictors for surgical revision and long-term disability. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(2):172-177.

26. Waterman BR, Liu J, Newcomb R, Schoenfeld AJ, Orr JD, Belmont PJ Jr. Risk factors for chronic exertional compartment syndrome in a physically active military population. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2545-2549.

27. Chalmers PN, Gupta AK, Rahman Z, Bruce B, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Predictors of early complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):856-860.

28. Dunn JC, Lanzi J, Kusnezov N, Bader J, Waterman BR, Belmont PJ Jr. Predictors of length of stay after elective total shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(5):754-759.

29. Hayes PR, Flatow EL. Total shoulder arthroplasty in the young patient. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50;73-88.

30. Rispoli DM, Sperling JW, Athwal GS, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Humeral head replacement for the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(12):2637-2644.

31. Radnay CS, Setter KJ, Chambers L, Levine WN, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS. Total shoulder replacement compared with humeral head replacement for the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(4):396-402.

32. Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(1):26-34.

33. Edwards TB, Kadakia NR, Boulahia A, et al. A comparison of hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results of a multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(3):

207-213.

34. Bryant D, Litchfield R, Sandow M, Gartsman GM, Guyatt G, Kirkley A. A comparison of pain, strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis of the shoulder. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):1947-1956.

35. Bailie DS, Llinas PJ, Ellenbecker TS. Cementless humeral resurfacing arthroplasty in active patients less than fifty-five years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):110-117.

36. Ball CM, Galatz LM, Yamaguchi K. Meniscal allograft interposition arthroplasty for the arthritic shoulder: description of a new surgical technique. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;2:247-254.

37. Elhassan B, Ozbaydar M, Diller D, Higgins LD, Warner JJ. Soft-tissue resurfacing of the glenoid in the treatment of glenohumeral arthritis in active patients less than fifty years old. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(2):419-424.

38. Krishnan SG, Nowinski RJ, Harrison D, Burkhead WZ. Humeral hemiarthroplasty with biologic resurfacing of the glenoid for glenohumeral arthritis. Two to fifteen-year outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):727-734.

39. Lee KT, Bell S, Salmon J. Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty of the shoulder with biologic resurfacing of the glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):915-919.

40. Nicholson GP, Goldstein JL, Romeo AA, et al. Lateral meniscus allograft biologic glenoid arthroplasty in total shoulder arthroplasty for young shoulders with degenerative joint disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5 suppl):S261-S266.

41. Carroll RM, Izquierdo R, Vazquez M, Blaine TA, Levine WN, Bigliani LU. Conversion of painful hemiarthroplasty to total shoulder arthroplasty: long-term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(6):599-603.

42. Clinton J, Franta AK, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Matsen FA 3rd. Nonprosthetic glenoid arthroplasty with humeral hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty yield similar self-assessed outcomes in the management of comparable patients with glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5):534-538.

43. Gilmer BB, Comstock BA, Jette JL, Warme WJ, Jackins SE, Matsen FA. The prognosis for improvement in comfort and function after the ream-and-run arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthritis: an analysis of 176 consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14):e102.

44. Franta AK, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Neradilek B, Matsen FA 3rd. The complex characteristics of 282 unsatisfactory shoulder arthroplasties. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5):555-562.

45. Godenèche A, Boileau P, Favard L, et al. Prosthetic replacement in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the shoulder: early results of 268 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(1):11-18.

46. Jensen KL, Rockwood CA Jr. Shoulder arthroplasty in recreational golfers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(4):362-367.

47. Kirchhoff C, Imhoff AB, Hinterwimmer S. Winter sports and shoulder arthroplasty [in German]. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2008;22(3):153-158.

48. Raiss P, Edwards TB, Deutsch A, et al. Radiographic changes around humeral components in shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(7):e54.

Although total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) has proved to be a reliable solution in older patients, treatment in younger patients with glenohumeral arthritis remains controversial, and there are still few reliable long-term surgical options.1-8 These options include abrasion arthroplasty and arthroscopic management,9,10 biologic glenoid resurfacing,11,12 and humeral hemiarthroplasty with13 or without14,15 glenoid treatment and anatomical TSA.

In the younger cohort, 20-year TSA survivorship rates up to 84% have been reported, and unsatisfactory subjective outcomes have been unacceptably high.16 In addition, there is a paucity of literature addressing the impact of TSA on return to sport. Recommendations on returning to an athletic life style are based largely on surveys of expert opinion17,18 and heterogeneous studies of either older patients (eg, age >50-55 years) who are active19-21 or younger patients with no defined level of activity.5,7,8,16,22-24

To our knowledge, no one has evaluated the short-term morbidity and clinical outcomes within a young, high-demand patient population, such as the US military. Therefore, we conducted a study to evaluate the clinical success and complications of TSA performed for glenohumeral arthritis in a young, active population. We hypothesized that patients who had undergone TSA would have a low rate of return to duty, an increased rate of component failure, and a higher reoperation rate because of increased upper extremity demands.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining protocol approval from the William Beaumont Army Medical Center Institutional Review Board, we searched the Military Health System (MHS) Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (M2) database to retrospectively review the cases of all tri-service US military service members who had undergone primary anatomical TSA (Current Procedural Terminology code 23472) between January 1, 2007 and June 31, 2014. This was a multisurgeon, multicenter study. Patient exclusion criteria were nonmilitary or retired status at time of surgery; primary surgery consisting of limited glenohumeral resurfacing procedure, hemiarthroplasty, or reverse TSA; surgery for acute proximal humerus fracture; rotator cuff deficiency diagnosed before or during surgery; and insufficient follow-up (eg, <12 months, unless medically separated beforehand).

The M2 database is an established tool that has been used for clinical outcomes research on treatment of a variety of orthopedic conditions.25,26 The Medical Data Repository, which is operated by MHS, is populated by its military healthcare providers. The MHS, which offers worldwide coverage for all beneficiaries either at Department of Defense facilities or purchased using civilian providers, is among the largest known closed healthcare systems.

All active-duty US military service members are uniformly required to adhere to stringent and regularly evaluated physical fitness standards, which typically exceed those of average civilians. Routine physical training is required in the form of aerobic fitness, weight training, tactical field exercises, and core military tasks, such as the ability to march at least 2 miles while carrying heavy fighting loads. In addition to satisfying required height and weight standards, all service members are subject to semiannual service-specific physical fitness evaluations inclusive of timed push-ups, sit-ups, and an aerobic event. Service members may also be required to maintain a level of physical training above these baseline standards, contingent on their branch of service, rank, and military occupational specialty. If a service member is unable to maintain these standards, medical separation may be initiated.

Demographic and occupational data were extracted from the database. These data included age, sex, military rank, and branch of service. Line-by-line analysis of the Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application (Version 22; 3M) electronic medical record was then performed to confirm the underlying diagnosis, surgical procedure, and surgery date. Further chart review yielded additional patient-based factors (eg, laterality, hand dominance, presence and type of prior shoulder surgeries) and surgical factors (eg, surgery indication, implant design). We evaluated clinical and functional outcomes as well as perioperative complications, including both major and minor systemic and local complications as previously described27,28; preoperative and postoperative range of motion (ROM) and self-reported pain score (SRPS, scale 1-10) as measured by physical therapist and surgeon at follow-up; secondary surgical interventions; timing of return to duty; and postoperative deployment history. The primary outcome measures were revision reoperation after index procedure, and military discharge for persistent shoulder-related disability. Clinical failure was defined as component failure or reoperation. Medical Evaluation Board (MEB) is a formal separation from the military in which it is deemed that a service member is no longer able to fulfill his or her duty because of a medical condition.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using statistical means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and/or SDs. Categorical data were reported as frequencies or percentages. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the correlation between possible risk factors and the primary outcome measures. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

We identified 24 service members (26 shoulders) who had undergone anatomical TSA during the study period (Table 1). Mean (SD) age was 45.8 (4.5) years (range, 35-54 years), and the cohort was predominately male (25/26 shoulders; 96.2%). Most cohort members were of senior enlisted rank (14, 58.3%), and the US Army was the predominant branch of military service (13, 54.2%). The right side was the operative extremity in 7 cases (26.9%), and the dominant shoulder was involved in 6 cases (23.1%). Two patients (8.3%) underwent staged bilateral TSA. Most patients (76.9%) underwent TSA on the nondominant extremity.

Surgical Variables

TSA was indicated for post-instability arthropathy in 13 cases (50.0%), posttraumatic osteoarthritis in 7 cases (26.9%), and unspecified glenohumeral arthritis, which includes primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis, in 5 cases (19.2%) (Table 2). One case was attributed to iatrogenically induced chondrolysis secondary to intra-articular lidocaine pump. Twelve patients (46.2%) had at least 1 previous surgery. Of the shoulders with instability, 10 (76.9%) had undergone a total of 14 surgical stabilization procedures—10 anterior labral repairs, 2 posterior labral repairs, and 2 capsular plications. The other shoulders had undergone a total of 18 procedures, which included 4 rotator cuff repairs and 3 cartilage restoration procedures.

Clinical Outcomes

Mean (SD) follow-up was 41.0 (21.3) months (range, 11.6-97.6 months). All but 1 shoulder (96.2%) had follow-up of 12 months or more (the only patient with shorter follow-up was because of MEB), and 76.9% of patients had follow-up of 24 months or more (4 of the 6 patients with follow-up under 24 months were medically separated) (Table 3). In all cases, mean ROM improved with respect to flexion, abduction, and external rotation. At final follow-up, mean (SD) ROM was 138° (36°) forward flexion (range, 60°-180°), 125° (39°) abduction (range, 45°-180°), 48° (19°) external rotation at 0° abduction (range, 20°-90°), and 80° (9.4°) external rotation at 90° abduction (range, 70°-90°). Preoperative flexion, abduction, and external rotation at 0° and 90° abduction were all improved at final follow-up. The most improvement in ROM occurred within 6 months after surgery.

Overall patient satisfaction with surgery was 92.3% (n = 24). Ultimately, 18 (72.0%) of 25 shoulders with follow-up of 1 year or more were able to return to active duty within 1 year after surgery, though only 10 (45.5%) of 22 with follow-up of 2 years or more remained active 2 years after surgery. Furthermore, 5 patients (20.8%) were deployed after surgery, and all were still on active duty at final follow-up. By final follow-up, 9 (37.5%) of 24 service members were unable to return to military function; 7 had been medically discharged from the military for persistent shoulder disability, and 2 were in the process of being medically discharged.

In all cases, SRPS improved from before surgery (5.2 out of 10) to final follow-up (1.4). At final follow-up, 22 patients (88.0%) reported mild pain (0-3), and no one had pain above 6.

Complications

Nine patients had a total of 12 postoperative complications (46.2%): 6 component failures (23.1%), 2 neurologic injuries (7.7%; 1 permanent axillary nerve injury, 1 transient brachial plexus neuritis), 2 cases of adhesive capsulitis (7.7%), and 2 episodes of venous thrombosis (7.7%; 1 superficial, 1 deep) (Table 4). There were no documented infections. Six reoperations (23.1%) were performed for the 6 component failures (2 traumatic dislocations of prosthesis resulting in acute glenoid component failure, 3 cases of atraumatic glenoid loosening, 1 case of humeral stem loosening after periprosthetic fracture). Atraumatic glenoid component loosening occurred a mean (SD) of 40.6 (14.2) months after surgery (range, 20.8-54.2 months).

Surgical Failures

Eight service members underwent MEB. Six patients experienced component failure. Factors contributing to both clinical failure and separation from active duty by means of MEB were evaluated with univariate analysis (Table 5). No statistically significant risk factors, including surgical revision and presence of perioperative complications, were identified.

Discussion

We confirmed that our cohort of young service members (mean age, 45.8 years), who had undergone TSA for glenohumeral arthritis, had a relatively higher rate of component failure (23.1%) and a higher reoperation rate (23.1%) with low rates of return to military duty at short-term to midterm follow-up. Our results parallel those of a limited series with a younger cohort (Table 6).7,16,19,21,23,24 The high demand and increased life expectancy of the younger patients with glenohumeral arthritis potentiates the risk of complications, component loosening, and ultimate failure.29 To our knowledge, the present article is the first to report clinical and functional outcomes and perioperative risk profiles in a homogenously young, active military cohort after TSA.

The mean age of our study population (46 years) is one of the lowest in the literature. TSA in younger patients (age, <50-55 years) and older, active patients (>55 years) has received increased attention as a result of the expanding indications and growing popularity of TSA in these groups. Other studies have upheld the efficacy of TSA in achieving predictable pain relief and functional improvement in a diverse and predominantly elderly population.15,30-34 Alternative treatments, including humeral head resurfacing15,30,35 and soft-tissue interposition,15,36-40 have also shown inferior short- and long-term results in terms of longevity and degree of clinical or functional improvement.31-34,41 In addition, the ream-and-run technique has had promising early results by improving glenohumeral kinematics, pain relief, and shoulder function.13,42,43 However, although implantation of a glenoid component is avoided in young, active people because of reduced longevity and higher rates of component failure, the trade-offs are inadequately treated glenoid disease, suboptimal pain relief, and progression of glenoid arthritis eventually requiring revision. Furthermore, midterm and long-term survivorship of TSA in general is unknown, and there remain few good options for treating end-stage arthritis in young, active patients.

Our cohort had high rates of complications (46.2%) and revisions (23.1%). Two in 5 patients had postoperative complications, most commonly component failure resulting in reoperation. In the literature, complication rates among young patients who underwent TSA are much lower (4.8%-10.9%).16,23,24 Our cohort’s most common complication was component failure (23.1%), which was most often attributed to atraumatic, aseptic glenoid component loosening and required reoperation. Previously reported revision rates in a young population that underwent TSA (0%-11%)16,23,24 were also significantly lower than those in the present analysis (23.1%), underscoring the impact of operative indications, postoperative activity levels, and occupational demands on ultimate failure rates. Interestingly, all revisions in our study were for component failure, whereas previous reports have described a higher rate for infection.22 However, the same studies also found glenoid lucency rates as high as 76% at 10-year follow-up.16 Furthermore, in a review of 136 TSAs with unsatisfactory outcomes, glenoid loosening was the most common reason for presenting to clinic after surgery.44 Specifically, our population had a high rate of glenohumeral arthritis secondary to instability (50.0%) and posttraumatic osteoarthritis (26.9%). For many reasons, outcomes were worse in younger patients with a history of glenohumeral instability33 than in older patients without a high incidence of instability.45 This young cohort with higher demands may have had accelerated polyethylene wear patterns caused by repetitive overhead activity, which may have arisen because of a higher functional profile after surgery and greater patient expectations after arthroplasty. In addition, patients with a history of instability may have altered glenohumeral anatomy, especially with previous arthroscopic or open stabilization procedures. Anatomical changes include excessive posterior glenoid wear, internal rotation contracture, patulous capsular tissue, static or dynamic posterior humeral subluxation, and possible overconstraint after prior stabilization procedures. Almost half of our population had a previous surgery; our patients averaged 1.7 previous surgeries each.

Although estimates of component survivorship at a high-volume civilian tertiary-referral center were as high as 97% at 10 years and 84% at 20 years,7,16 10-year survivorship in patients with a history of instability was only 61%.3 TSA survivorship in our young, active cohort is already foreseeably dramatically reduced, given the 23.1% revision rate at 28.5-month follow-up. This consideration must be addressed during preoperative counseling with the young patient with glenohumeral arthritis and a history of shoulder instability.

Despite the high rates of complications and revisions in our study, 92.3% of patients were satisfied with surgery, 88.0% experienced minimal persistence of pain (mean 3.8-point decrease on SRPS), and 100% maintained improved ROM at final follow-up. Satisfaction in the young population has varied significantly, from 52% to 95%, generally on the basis of physical activity.16,22-24 The reasonable rate of postoperative satisfaction in the present analysis is comparable to what has been reported in patients of a similar age (Table 6).7,16,22 However, despite high satisfaction and pain relief, patients were inconsistently able to return to the upper limits of physical activity required of active-duty military service. In addition, we cannot exclude secondary gain motivations for pursuing medical retirement, similar to that seen in patients receiving worker’s compensation.

Other authors have conversely found more favorable functional outcomes and survivorship rates.23,24 In a retrospective review of 46 TSAs in patients 55 years or younger, Bartelt and colleagues24 found sustained improvements in pain, ROM, and satisfaction at 7-year follow-up.24 Raiss and colleagues23 conducted a prospective study of TSA outcomes in 21 patients with a mean age of 55 years and a mean follow-up of 7 years and reported no revisions and only 1 minor complication, a transient brachial plexus palsy.23 The discrepancy between these studies may reflect different activity levels and underlying pathology between cohorts. The present population is unique in that it represents a particularly difficult confluence of factors for shoulder arthroplasty surgeons. The high activity, significant overhead and lifting occupational demands, and discordant patient expectations of this military cohort place a significant functional burden on the implants, the glenoid component in particular. Furthermore, this patient group has a higher incidence of more complex glenohumeral pathology resulting in instability, posttraumatic, or capsulorrhaphy arthropathy, and multiple prior arthroscopic and open stabilization procedures.

At final follow-up, only 33% of our patients were still on activity duty, 37.5% had completed or were completing medical separation from the military after surgery for persistent shoulder disability, and 37.5% were retired from the military. Five patients (20.8%) deployed after surgery. This young, active cohort of service members who had TSA for glenohumeral arthritis faced a unique set of tremendous physical demands. A retrospective case series investigated return to sport in 100 consecutive patients (mean age, 68.9 years) who were participating in recreational and competitive athletics and underwent unilateral TSA.21 The patients were engaged most commonly in swimming (20.4%), golf (16.3%), cycling (16.3%), and fitness training (16.3%). The authors found that, at a mean follow-up of 2.8 years, 49 patients (89%) were able to continue in sports, though 36.7% thought their sport activity was restricted after TSA. In another retrospective case series (61 TSAs), McCarty and colleagues19 found that 48 patients (71%) were improved in their sports participation, and 50% increased their frequency of participation after surgery.

There are no specific recommendations on returning to military service or high-level sport after surgery. Recommendations on returning to sport after TSA have been based largely on small case series involving specific sports46,47 and surveys of expert opinion.17,18 In a survey on postoperative physical activity in young patients after TSA conducted by Healy and colleagues,17 35 American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons members recommended avoiding contact and impact sports while permitting return to nonimpact sports, such as swimming, which may still impart significant stress to the glenohumeral joint. In an international survey of 101 shoulder and elbow surgeons, Magnussen and colleagues18 also found that most recommended avoiding a return to impact sports that require intensive upper extremity demands and permitting full return to sports at preoperative levels. This likely is a result of the perception that most of these patients having TSA are older and have less rigorous involvement in sports at the outset and a lower propensity for adverse patient outcomes. However, these recommendations may place a younger, more high-demand patient at significantly greater risk. The active-duty cohort engages in daily physical training, including push-ups and frequent overhead lifting, which could account for the high failure rates and low incidence of postoperative deployment. Although TSA seems to demonstrate good initial results in terms of return to high-demand activities, the return-to-duty profile in our study highlights the potential pitfalls of TSA in active individuals attempting to return to high-demand preoperative function.

Our analysis was limited by the fact that we used a small patient cohort, contributing to underpowered analysis of the potential risk factors predictive of reoperation and medical discharge. Although our minimum follow-up was 12 months, with the exception of 1 patient who was medically separated at 11.6 months because of shoulder disability, we captured 5 patients (19.2%) who underwent medical separation but who would otherwise be excluded. Therefore, this limitation is not major in that, with a longer minimum follow-up, we would be excluding a significant number of patients with such persistent disability after TSA that they would not be able to return to duty at anywhere near their previous level. In this retrospective study, we were additionally limited to analysis of the data in the medical records and could not control for variables such as surgeon technique, implant choice, and experience. Complete radiographic images were not available, limiting analysis of radiographic outcomes. Given the lack of a standardized preoperative imaging protocol, we could not evaluate glenoid version on axial imaging. It is possible that some patients with early aseptic glenoid loosening had posterior subluxation or a Walch B2 glenoid, which has a higher failure rate.48 The strengths of this study include its unique analysis of a homogeneous young, active, high-risk patient cohort within a closed healthcare system. In the military, these patients are subject to intense daily physical and occupational demands. In addition, the clinical and functional outcomes we studied are patient-centered and therefore relevant during preoperative counseling. Further investigations might focus on validated outcome measures and on midterm to long-term TSA outcomes in an active military population vis-à-vis other alternatives for clinical management.

Conclusion

By a mean follow-up of 3.5 years, only a third of the service members had returned to active duty, roughly a third had retired, and more than a third had been medically discharged because of persistent disability attributable to the shoulder. Despite initial improvements in ROM and pain, midterm outcomes were poor. The short-term complication rate (46.2%) and the rate of reoperation for component failure (23.1%) should be emphasized during preoperative counseling.

Although total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) has proved to be a reliable solution in older patients, treatment in younger patients with glenohumeral arthritis remains controversial, and there are still few reliable long-term surgical options.1-8 These options include abrasion arthroplasty and arthroscopic management,9,10 biologic glenoid resurfacing,11,12 and humeral hemiarthroplasty with13 or without14,15 glenoid treatment and anatomical TSA.

In the younger cohort, 20-year TSA survivorship rates up to 84% have been reported, and unsatisfactory subjective outcomes have been unacceptably high.16 In addition, there is a paucity of literature addressing the impact of TSA on return to sport. Recommendations on returning to an athletic life style are based largely on surveys of expert opinion17,18 and heterogeneous studies of either older patients (eg, age >50-55 years) who are active19-21 or younger patients with no defined level of activity.5,7,8,16,22-24

To our knowledge, no one has evaluated the short-term morbidity and clinical outcomes within a young, high-demand patient population, such as the US military. Therefore, we conducted a study to evaluate the clinical success and complications of TSA performed for glenohumeral arthritis in a young, active population. We hypothesized that patients who had undergone TSA would have a low rate of return to duty, an increased rate of component failure, and a higher reoperation rate because of increased upper extremity demands.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining protocol approval from the William Beaumont Army Medical Center Institutional Review Board, we searched the Military Health System (MHS) Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (M2) database to retrospectively review the cases of all tri-service US military service members who had undergone primary anatomical TSA (Current Procedural Terminology code 23472) between January 1, 2007 and June 31, 2014. This was a multisurgeon, multicenter study. Patient exclusion criteria were nonmilitary or retired status at time of surgery; primary surgery consisting of limited glenohumeral resurfacing procedure, hemiarthroplasty, or reverse TSA; surgery for acute proximal humerus fracture; rotator cuff deficiency diagnosed before or during surgery; and insufficient follow-up (eg, <12 months, unless medically separated beforehand).

The M2 database is an established tool that has been used for clinical outcomes research on treatment of a variety of orthopedic conditions.25,26 The Medical Data Repository, which is operated by MHS, is populated by its military healthcare providers. The MHS, which offers worldwide coverage for all beneficiaries either at Department of Defense facilities or purchased using civilian providers, is among the largest known closed healthcare systems.

All active-duty US military service members are uniformly required to adhere to stringent and regularly evaluated physical fitness standards, which typically exceed those of average civilians. Routine physical training is required in the form of aerobic fitness, weight training, tactical field exercises, and core military tasks, such as the ability to march at least 2 miles while carrying heavy fighting loads. In addition to satisfying required height and weight standards, all service members are subject to semiannual service-specific physical fitness evaluations inclusive of timed push-ups, sit-ups, and an aerobic event. Service members may also be required to maintain a level of physical training above these baseline standards, contingent on their branch of service, rank, and military occupational specialty. If a service member is unable to maintain these standards, medical separation may be initiated.

Demographic and occupational data were extracted from the database. These data included age, sex, military rank, and branch of service. Line-by-line analysis of the Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application (Version 22; 3M) electronic medical record was then performed to confirm the underlying diagnosis, surgical procedure, and surgery date. Further chart review yielded additional patient-based factors (eg, laterality, hand dominance, presence and type of prior shoulder surgeries) and surgical factors (eg, surgery indication, implant design). We evaluated clinical and functional outcomes as well as perioperative complications, including both major and minor systemic and local complications as previously described27,28; preoperative and postoperative range of motion (ROM) and self-reported pain score (SRPS, scale 1-10) as measured by physical therapist and surgeon at follow-up; secondary surgical interventions; timing of return to duty; and postoperative deployment history. The primary outcome measures were revision reoperation after index procedure, and military discharge for persistent shoulder-related disability. Clinical failure was defined as component failure or reoperation. Medical Evaluation Board (MEB) is a formal separation from the military in which it is deemed that a service member is no longer able to fulfill his or her duty because of a medical condition.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using statistical means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and/or SDs. Categorical data were reported as frequencies or percentages. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the correlation between possible risk factors and the primary outcome measures. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

We identified 24 service members (26 shoulders) who had undergone anatomical TSA during the study period (Table 1). Mean (SD) age was 45.8 (4.5) years (range, 35-54 years), and the cohort was predominately male (25/26 shoulders; 96.2%). Most cohort members were of senior enlisted rank (14, 58.3%), and the US Army was the predominant branch of military service (13, 54.2%). The right side was the operative extremity in 7 cases (26.9%), and the dominant shoulder was involved in 6 cases (23.1%). Two patients (8.3%) underwent staged bilateral TSA. Most patients (76.9%) underwent TSA on the nondominant extremity.

Surgical Variables

TSA was indicated for post-instability arthropathy in 13 cases (50.0%), posttraumatic osteoarthritis in 7 cases (26.9%), and unspecified glenohumeral arthritis, which includes primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis, in 5 cases (19.2%) (Table 2). One case was attributed to iatrogenically induced chondrolysis secondary to intra-articular lidocaine pump. Twelve patients (46.2%) had at least 1 previous surgery. Of the shoulders with instability, 10 (76.9%) had undergone a total of 14 surgical stabilization procedures—10 anterior labral repairs, 2 posterior labral repairs, and 2 capsular plications. The other shoulders had undergone a total of 18 procedures, which included 4 rotator cuff repairs and 3 cartilage restoration procedures.

Clinical Outcomes

Mean (SD) follow-up was 41.0 (21.3) months (range, 11.6-97.6 months). All but 1 shoulder (96.2%) had follow-up of 12 months or more (the only patient with shorter follow-up was because of MEB), and 76.9% of patients had follow-up of 24 months or more (4 of the 6 patients with follow-up under 24 months were medically separated) (Table 3). In all cases, mean ROM improved with respect to flexion, abduction, and external rotation. At final follow-up, mean (SD) ROM was 138° (36°) forward flexion (range, 60°-180°), 125° (39°) abduction (range, 45°-180°), 48° (19°) external rotation at 0° abduction (range, 20°-90°), and 80° (9.4°) external rotation at 90° abduction (range, 70°-90°). Preoperative flexion, abduction, and external rotation at 0° and 90° abduction were all improved at final follow-up. The most improvement in ROM occurred within 6 months after surgery.

Overall patient satisfaction with surgery was 92.3% (n = 24). Ultimately, 18 (72.0%) of 25 shoulders with follow-up of 1 year or more were able to return to active duty within 1 year after surgery, though only 10 (45.5%) of 22 with follow-up of 2 years or more remained active 2 years after surgery. Furthermore, 5 patients (20.8%) were deployed after surgery, and all were still on active duty at final follow-up. By final follow-up, 9 (37.5%) of 24 service members were unable to return to military function; 7 had been medically discharged from the military for persistent shoulder disability, and 2 were in the process of being medically discharged.

In all cases, SRPS improved from before surgery (5.2 out of 10) to final follow-up (1.4). At final follow-up, 22 patients (88.0%) reported mild pain (0-3), and no one had pain above 6.

Complications

Nine patients had a total of 12 postoperative complications (46.2%): 6 component failures (23.1%), 2 neurologic injuries (7.7%; 1 permanent axillary nerve injury, 1 transient brachial plexus neuritis), 2 cases of adhesive capsulitis (7.7%), and 2 episodes of venous thrombosis (7.7%; 1 superficial, 1 deep) (Table 4). There were no documented infections. Six reoperations (23.1%) were performed for the 6 component failures (2 traumatic dislocations of prosthesis resulting in acute glenoid component failure, 3 cases of atraumatic glenoid loosening, 1 case of humeral stem loosening after periprosthetic fracture). Atraumatic glenoid component loosening occurred a mean (SD) of 40.6 (14.2) months after surgery (range, 20.8-54.2 months).

Surgical Failures

Eight service members underwent MEB. Six patients experienced component failure. Factors contributing to both clinical failure and separation from active duty by means of MEB were evaluated with univariate analysis (Table 5). No statistically significant risk factors, including surgical revision and presence of perioperative complications, were identified.

Discussion

We confirmed that our cohort of young service members (mean age, 45.8 years), who had undergone TSA for glenohumeral arthritis, had a relatively higher rate of component failure (23.1%) and a higher reoperation rate (23.1%) with low rates of return to military duty at short-term to midterm follow-up. Our results parallel those of a limited series with a younger cohort (Table 6).7,16,19,21,23,24 The high demand and increased life expectancy of the younger patients with glenohumeral arthritis potentiates the risk of complications, component loosening, and ultimate failure.29 To our knowledge, the present article is the first to report clinical and functional outcomes and perioperative risk profiles in a homogenously young, active military cohort after TSA.

The mean age of our study population (46 years) is one of the lowest in the literature. TSA in younger patients (age, <50-55 years) and older, active patients (>55 years) has received increased attention as a result of the expanding indications and growing popularity of TSA in these groups. Other studies have upheld the efficacy of TSA in achieving predictable pain relief and functional improvement in a diverse and predominantly elderly population.15,30-34 Alternative treatments, including humeral head resurfacing15,30,35 and soft-tissue interposition,15,36-40 have also shown inferior short- and long-term results in terms of longevity and degree of clinical or functional improvement.31-34,41 In addition, the ream-and-run technique has had promising early results by improving glenohumeral kinematics, pain relief, and shoulder function.13,42,43 However, although implantation of a glenoid component is avoided in young, active people because of reduced longevity and higher rates of component failure, the trade-offs are inadequately treated glenoid disease, suboptimal pain relief, and progression of glenoid arthritis eventually requiring revision. Furthermore, midterm and long-term survivorship of TSA in general is unknown, and there remain few good options for treating end-stage arthritis in young, active patients.

Our cohort had high rates of complications (46.2%) and revisions (23.1%). Two in 5 patients had postoperative complications, most commonly component failure resulting in reoperation. In the literature, complication rates among young patients who underwent TSA are much lower (4.8%-10.9%).16,23,24 Our cohort’s most common complication was component failure (23.1%), which was most often attributed to atraumatic, aseptic glenoid component loosening and required reoperation. Previously reported revision rates in a young population that underwent TSA (0%-11%)16,23,24 were also significantly lower than those in the present analysis (23.1%), underscoring the impact of operative indications, postoperative activity levels, and occupational demands on ultimate failure rates. Interestingly, all revisions in our study were for component failure, whereas previous reports have described a higher rate for infection.22 However, the same studies also found glenoid lucency rates as high as 76% at 10-year follow-up.16 Furthermore, in a review of 136 TSAs with unsatisfactory outcomes, glenoid loosening was the most common reason for presenting to clinic after surgery.44 Specifically, our population had a high rate of glenohumeral arthritis secondary to instability (50.0%) and posttraumatic osteoarthritis (26.9%). For many reasons, outcomes were worse in younger patients with a history of glenohumeral instability33 than in older patients without a high incidence of instability.45 This young cohort with higher demands may have had accelerated polyethylene wear patterns caused by repetitive overhead activity, which may have arisen because of a higher functional profile after surgery and greater patient expectations after arthroplasty. In addition, patients with a history of instability may have altered glenohumeral anatomy, especially with previous arthroscopic or open stabilization procedures. Anatomical changes include excessive posterior glenoid wear, internal rotation contracture, patulous capsular tissue, static or dynamic posterior humeral subluxation, and possible overconstraint after prior stabilization procedures. Almost half of our population had a previous surgery; our patients averaged 1.7 previous surgeries each.

Although estimates of component survivorship at a high-volume civilian tertiary-referral center were as high as 97% at 10 years and 84% at 20 years,7,16 10-year survivorship in patients with a history of instability was only 61%.3 TSA survivorship in our young, active cohort is already foreseeably dramatically reduced, given the 23.1% revision rate at 28.5-month follow-up. This consideration must be addressed during preoperative counseling with the young patient with glenohumeral arthritis and a history of shoulder instability.

Despite the high rates of complications and revisions in our study, 92.3% of patients were satisfied with surgery, 88.0% experienced minimal persistence of pain (mean 3.8-point decrease on SRPS), and 100% maintained improved ROM at final follow-up. Satisfaction in the young population has varied significantly, from 52% to 95%, generally on the basis of physical activity.16,22-24 The reasonable rate of postoperative satisfaction in the present analysis is comparable to what has been reported in patients of a similar age (Table 6).7,16,22 However, despite high satisfaction and pain relief, patients were inconsistently able to return to the upper limits of physical activity required of active-duty military service. In addition, we cannot exclude secondary gain motivations for pursuing medical retirement, similar to that seen in patients receiving worker’s compensation.

Other authors have conversely found more favorable functional outcomes and survivorship rates.23,24 In a retrospective review of 46 TSAs in patients 55 years or younger, Bartelt and colleagues24 found sustained improvements in pain, ROM, and satisfaction at 7-year follow-up.24 Raiss and colleagues23 conducted a prospective study of TSA outcomes in 21 patients with a mean age of 55 years and a mean follow-up of 7 years and reported no revisions and only 1 minor complication, a transient brachial plexus palsy.23 The discrepancy between these studies may reflect different activity levels and underlying pathology between cohorts. The present population is unique in that it represents a particularly difficult confluence of factors for shoulder arthroplasty surgeons. The high activity, significant overhead and lifting occupational demands, and discordant patient expectations of this military cohort place a significant functional burden on the implants, the glenoid component in particular. Furthermore, this patient group has a higher incidence of more complex glenohumeral pathology resulting in instability, posttraumatic, or capsulorrhaphy arthropathy, and multiple prior arthroscopic and open stabilization procedures.

At final follow-up, only 33% of our patients were still on activity duty, 37.5% had completed or were completing medical separation from the military after surgery for persistent shoulder disability, and 37.5% were retired from the military. Five patients (20.8%) deployed after surgery. This young, active cohort of service members who had TSA for glenohumeral arthritis faced a unique set of tremendous physical demands. A retrospective case series investigated return to sport in 100 consecutive patients (mean age, 68.9 years) who were participating in recreational and competitive athletics and underwent unilateral TSA.21 The patients were engaged most commonly in swimming (20.4%), golf (16.3%), cycling (16.3%), and fitness training (16.3%). The authors found that, at a mean follow-up of 2.8 years, 49 patients (89%) were able to continue in sports, though 36.7% thought their sport activity was restricted after TSA. In another retrospective case series (61 TSAs), McCarty and colleagues19 found that 48 patients (71%) were improved in their sports participation, and 50% increased their frequency of participation after surgery.

There are no specific recommendations on returning to military service or high-level sport after surgery. Recommendations on returning to sport after TSA have been based largely on small case series involving specific sports46,47 and surveys of expert opinion.17,18 In a survey on postoperative physical activity in young patients after TSA conducted by Healy and colleagues,17 35 American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons members recommended avoiding contact and impact sports while permitting return to nonimpact sports, such as swimming, which may still impart significant stress to the glenohumeral joint. In an international survey of 101 shoulder and elbow surgeons, Magnussen and colleagues18 also found that most recommended avoiding a return to impact sports that require intensive upper extremity demands and permitting full return to sports at preoperative levels. This likely is a result of the perception that most of these patients having TSA are older and have less rigorous involvement in sports at the outset and a lower propensity for adverse patient outcomes. However, these recommendations may place a younger, more high-demand patient at significantly greater risk. The active-duty cohort engages in daily physical training, including push-ups and frequent overhead lifting, which could account for the high failure rates and low incidence of postoperative deployment. Although TSA seems to demonstrate good initial results in terms of return to high-demand activities, the return-to-duty profile in our study highlights the potential pitfalls of TSA in active individuals attempting to return to high-demand preoperative function.

Our analysis was limited by the fact that we used a small patient cohort, contributing to underpowered analysis of the potential risk factors predictive of reoperation and medical discharge. Although our minimum follow-up was 12 months, with the exception of 1 patient who was medically separated at 11.6 months because of shoulder disability, we captured 5 patients (19.2%) who underwent medical separation but who would otherwise be excluded. Therefore, this limitation is not major in that, with a longer minimum follow-up, we would be excluding a significant number of patients with such persistent disability after TSA that they would not be able to return to duty at anywhere near their previous level. In this retrospective study, we were additionally limited to analysis of the data in the medical records and could not control for variables such as surgeon technique, implant choice, and experience. Complete radiographic images were not available, limiting analysis of radiographic outcomes. Given the lack of a standardized preoperative imaging protocol, we could not evaluate glenoid version on axial imaging. It is possible that some patients with early aseptic glenoid loosening had posterior subluxation or a Walch B2 glenoid, which has a higher failure rate.48 The strengths of this study include its unique analysis of a homogeneous young, active, high-risk patient cohort within a closed healthcare system. In the military, these patients are subject to intense daily physical and occupational demands. In addition, the clinical and functional outcomes we studied are patient-centered and therefore relevant during preoperative counseling. Further investigations might focus on validated outcome measures and on midterm to long-term TSA outcomes in an active military population vis-à-vis other alternatives for clinical management.

Conclusion

By a mean follow-up of 3.5 years, only a third of the service members had returned to active duty, roughly a third had retired, and more than a third had been medically discharged because of persistent disability attributable to the shoulder. Despite initial improvements in ROM and pain, midterm outcomes were poor. The short-term complication rate (46.2%) and the rate of reoperation for component failure (23.1%) should be emphasized during preoperative counseling.

1. Tokish JM. The mature athlete’s shoulder. Sports Health. 2014;6(1):31-35.

2. Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of glenoid arthrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(6):860-867.

3. Sperling JW, Antuna SA, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck C, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty for arthritis after instability surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(10):1775-1781.

4. Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, et al; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(6):375-382.

5. Johnson MH, Paxton ES, Green A. Shoulder arthroplasty options in young (<50 years old) patients: review of current concepts. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(2):317-325.

6. Cole BJ, Yanke A, Provencher MT. Nonarthroplasty alternatives for the treatment of glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5 suppl):S231-S240.

7. Denard PJ, Raiss P, Sowa B, Walch G. Mid- to long-term follow-up of total shoulder arthroplasty using a keeled glenoid in young adults with primary glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):894-900.

8. Denard PJ, Wirth MA, Orfaly RM. Management of glenohumeral arthritis in the young adult. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(9):885-892.

9. Millett PJ, Horan MP, Pennock AT, Rios D. Comprehensive arthroscopic management (CAM) procedure: clinical results of a joint-preserving arthroscopic treatment for young, active patients with advanced shoulder osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):440-448.

10 Millett PJ, Gaskill TR. Arthroscopic management of glenohumeral arthrosis: humeral osteoplasty, capsular release, and arthroscopic axillary nerve release as a joint-preserving approach. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(9):1296-1303.

11. Savoie FH 3rd, Brislin KJ, Argo D. Arthroscopic glenoid resurfacing as a surgical treatment for glenohumeral arthritis in the young patient: midterm results. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):864-871.

12. Strauss EJ, Verma NN, Salata MJ, et al. The high failure rate of biologic resurfacing of the glenoid in young patients with glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(3):409-419.

13. Matsen FA 3rd, Warme WJ, Jackins SE. Can the ream and run procedure improve glenohumeral relationships and function for shoulders with the arthritic triad? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2088-2096.

14. Lo IK, Litchfield RB, Griffin S, Faber K, Patterson SD, Kirkley A. Quality-of-life outcome following hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(10):2178-2185.

15. Wirth M, Tapscott RS, Southworth C, Rockwood CA Jr. Treatment of glenohumeral arthritis with a hemiarthroplasty: a minimum five-year follow-up outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(5):964-973.

16. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Minimum fifteen-year follow-up of Neer hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged fifty years or younger. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(6):604-613.

17. Healy WL, Iorio R, Lemos MJ. Athletic activity after joint replacement. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(3):377-388.

18. Magnussen RA, Mallon WJ, Willems WJ, Moorman CT 3rd. Long-term activity restrictions after shoulder arthroplasty: an international survey of experienced shoulder surgeons. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):281-289.

19. McCarty EC, Marx RG, Maerz D, Altchek D, Warren RF. Sports participation after shoulder replacement surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1577-1581.

20. Schmidt-Wiethoff R, Wolf P, Lehmann M, Habermeyer P. Physical activity after shoulder arthroplasty [in German]. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2002;16(1):26-30.

21. Schumann K, Flury MP, Schwyzer HK, Simmen BR, Drerup S, Goldhahn J. Sports activity after anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):2097-2105.