User login

Journal of Hospital Medicine – Jan. 2018

BACKGROUND: Hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with chronic conditions are admitted to children’s hospitals. Despite multiple efforts to improve pediatric-adult health care transitions, little guidance exists for transitioning inpatient care.

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to characterize pediatric-adult inpatient care transitions across general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals.

DESIGN and SETTING: National survey of inpatient general pediatric service leaders at U.S. children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016.

MEASUREMENT: Questionnaires assessed institutional characteristics, presence of inpatient transition initiatives (having a specific process and/or leader), and 22 inpatient transition activities. Scales of highly correlated activities were created using exploratory factor analysis. Logistic regression identified associations among institutional characteristics, transition activities, and presence of an inpatient transition initiative.

RESULTS: Of 195 children’s hospitals, 96 responded (49.2% response rate). Transition initiatives were present at 38% of children’s hospitals, more often where there were providers who were trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics or where there were outpatient transition processes. Specific activities were infrequent and varied widely from 2.1% (systems to track youth in transition) to 40.5% (addressing potential insurance problems). Institutions with initiatives more often consistently performed the majority of activities, including using checklists and creating patient-centered transition care plans. Of remaining activities, half involved transition planning, the essential step between readiness and transfer.

CONCLUSION: Relatively few inpatient general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd transitions to adult-oriented inpatient care. Across institutions, there is wide variability in performance of activities to facilitate this transition. Feasible process and outcome measures are needed.

Also in JHM this month

Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery

AUTHORS: Joseph R. Sweigart, MD, FACP, FHM; David Aymond, MD; Alfred Burger, MD, FACP, SFHM; Andy Kelly, MAS, MS; Nick Marzano, Med; Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM; Peter Morris, MD; Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM; and Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, FCCM

Clinical decision making: Observing the smartphone user an observational study in predicting acute surgical patients’ suitability for discharge

AUTHORS: Richard Hoffmann, MBBS; Simon Harley, MBBS; Samuel Ellison, MBBS; and Peter G. Devitt, MBBS, FRACS

BACKGROUND: Hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with chronic conditions are admitted to children’s hospitals. Despite multiple efforts to improve pediatric-adult health care transitions, little guidance exists for transitioning inpatient care.

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to characterize pediatric-adult inpatient care transitions across general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals.

DESIGN and SETTING: National survey of inpatient general pediatric service leaders at U.S. children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016.

MEASUREMENT: Questionnaires assessed institutional characteristics, presence of inpatient transition initiatives (having a specific process and/or leader), and 22 inpatient transition activities. Scales of highly correlated activities were created using exploratory factor analysis. Logistic regression identified associations among institutional characteristics, transition activities, and presence of an inpatient transition initiative.

RESULTS: Of 195 children’s hospitals, 96 responded (49.2% response rate). Transition initiatives were present at 38% of children’s hospitals, more often where there were providers who were trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics or where there were outpatient transition processes. Specific activities were infrequent and varied widely from 2.1% (systems to track youth in transition) to 40.5% (addressing potential insurance problems). Institutions with initiatives more often consistently performed the majority of activities, including using checklists and creating patient-centered transition care plans. Of remaining activities, half involved transition planning, the essential step between readiness and transfer.

CONCLUSION: Relatively few inpatient general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd transitions to adult-oriented inpatient care. Across institutions, there is wide variability in performance of activities to facilitate this transition. Feasible process and outcome measures are needed.

Also in JHM this month

Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery

AUTHORS: Joseph R. Sweigart, MD, FACP, FHM; David Aymond, MD; Alfred Burger, MD, FACP, SFHM; Andy Kelly, MAS, MS; Nick Marzano, Med; Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM; Peter Morris, MD; Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM; and Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, FCCM

Clinical decision making: Observing the smartphone user an observational study in predicting acute surgical patients’ suitability for discharge

AUTHORS: Richard Hoffmann, MBBS; Simon Harley, MBBS; Samuel Ellison, MBBS; and Peter G. Devitt, MBBS, FRACS

BACKGROUND: Hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with chronic conditions are admitted to children’s hospitals. Despite multiple efforts to improve pediatric-adult health care transitions, little guidance exists for transitioning inpatient care.

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to characterize pediatric-adult inpatient care transitions across general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals.

DESIGN and SETTING: National survey of inpatient general pediatric service leaders at U.S. children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016.

MEASUREMENT: Questionnaires assessed institutional characteristics, presence of inpatient transition initiatives (having a specific process and/or leader), and 22 inpatient transition activities. Scales of highly correlated activities were created using exploratory factor analysis. Logistic regression identified associations among institutional characteristics, transition activities, and presence of an inpatient transition initiative.

RESULTS: Of 195 children’s hospitals, 96 responded (49.2% response rate). Transition initiatives were present at 38% of children’s hospitals, more often where there were providers who were trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics or where there were outpatient transition processes. Specific activities were infrequent and varied widely from 2.1% (systems to track youth in transition) to 40.5% (addressing potential insurance problems). Institutions with initiatives more often consistently performed the majority of activities, including using checklists and creating patient-centered transition care plans. Of remaining activities, half involved transition planning, the essential step between readiness and transfer.

CONCLUSION: Relatively few inpatient general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd transitions to adult-oriented inpatient care. Across institutions, there is wide variability in performance of activities to facilitate this transition. Feasible process and outcome measures are needed.

Also in JHM this month

Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery

AUTHORS: Joseph R. Sweigart, MD, FACP, FHM; David Aymond, MD; Alfred Burger, MD, FACP, SFHM; Andy Kelly, MAS, MS; Nick Marzano, Med; Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM; Peter Morris, MD; Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM; and Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, FCCM

Clinical decision making: Observing the smartphone user an observational study in predicting acute surgical patients’ suitability for discharge

AUTHORS: Richard Hoffmann, MBBS; Simon Harley, MBBS; Samuel Ellison, MBBS; and Peter G. Devitt, MBBS, FRACS

Transitioning from General Pediatric to Adult-Oriented Inpatient Care: National Survey of US Children’s Hospitals

Over 90% of children with chronic diseases now survive into adulthood.1,2 Clinical advances overcoming diseases previously fatal in childhood create new challenges for health systems with limited capacity to manage young adults with complicated and unfamiliar childhood-onset conditions. Consequently, improving the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented care has become a national priority.

Although major pediatric-adult transition initiatives—such as the Six Core Elements Framework,3 a technical brief from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,4 and joint statements from major medical societies5,6—outline key transition recommendations generally and for outpatients, they contain limited or no guidance specifically devoted to transitioning inpatient hospital care from pediatric to adult-oriented settings. Key unknowns include whether, when, and how to transition inpatient care from children’s to nonchildren’s hospitals and how this can be integrated into comprehensive youth-adult transition care.

Nevertheless, the number of discharges of 18- to 21-year-old patients with chronic conditions admitted to children’s hospitals is increasing at a faster rate than discharges of other age groups,7 suggesting both that the population is growing in size and that there are important barriers to transitioning these patients into nonchildren’s hospital settings. Spending on adult patients 18 years or older admitted to children’s hospitals has grown to $1 billion annually.8 Hospitalizations are a commonly proposed outcome measure of pediatric-adult transition work.1,9,10 For example, higher rates of avoidable hospitalizations during early adulthood have been observed for 15- to 22-year-olds with kidney failure cared for exclusively in adult-oriented facilities and during the years immediately after transfer to adult care.11

While research is beginning to describe outcomes of adult-aged patients with childhood-onset chronic conditions admitted to children’s hospitals,7,12,13 there has been no comprehensive description of efforts within children’s hospitals to transition such patients into adult-oriented inpatient settings. This information is necessary to outline institutional needs, delineate opportunities for improvement, and help clinicians strategically organize services for patients requiring this transition.

We sought to characterize the current state of the transition from pediatric- to adult-oriented inpatient care across general pediatric inpatient services at US children’s hospitals. We hypothesized that only a limited and inconsistent set of activities would be practiced. We also hypothesized that institutions having formal outpatient transition processes or providers with specialization to care for this age group, such as dual-trained internal medicine–pediatrics (med–peds) physicians, would report performing more activities.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, Participants

We conducted a national survey of leaders of inpatient general pediatrics services at US children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016. Hospitals were identified using the online Children’s Hospital Association directory. Hospitals without inpatient general pediatrics services (eg, rehabilitation or subspecialty-only facilities) were excluded.

We identified a single respondent from each of the 195 remaining children’s hospitals using a structured protocol. Phone numbers and e-mail addresses of potential respondents were gathered from hospital or medical school directories. Following a standard script, study team members contacted potential respondents to describe the purpose of the study and to confirm their contact information. Hospitals were also allowed to designate a different individual with more specific expertise to participate, when relevant (eg, specific faculty member leading a related quality improvement initiative). The goal was to identify a leader of inpatient care with the most knowledge of institutional practices related to the transition to adult inpatient care. Examples of respondent roles included director of inpatient pediatrics, chief of hospital medicine or general pediatrics, medical director, and similar titles.

Survey Elements

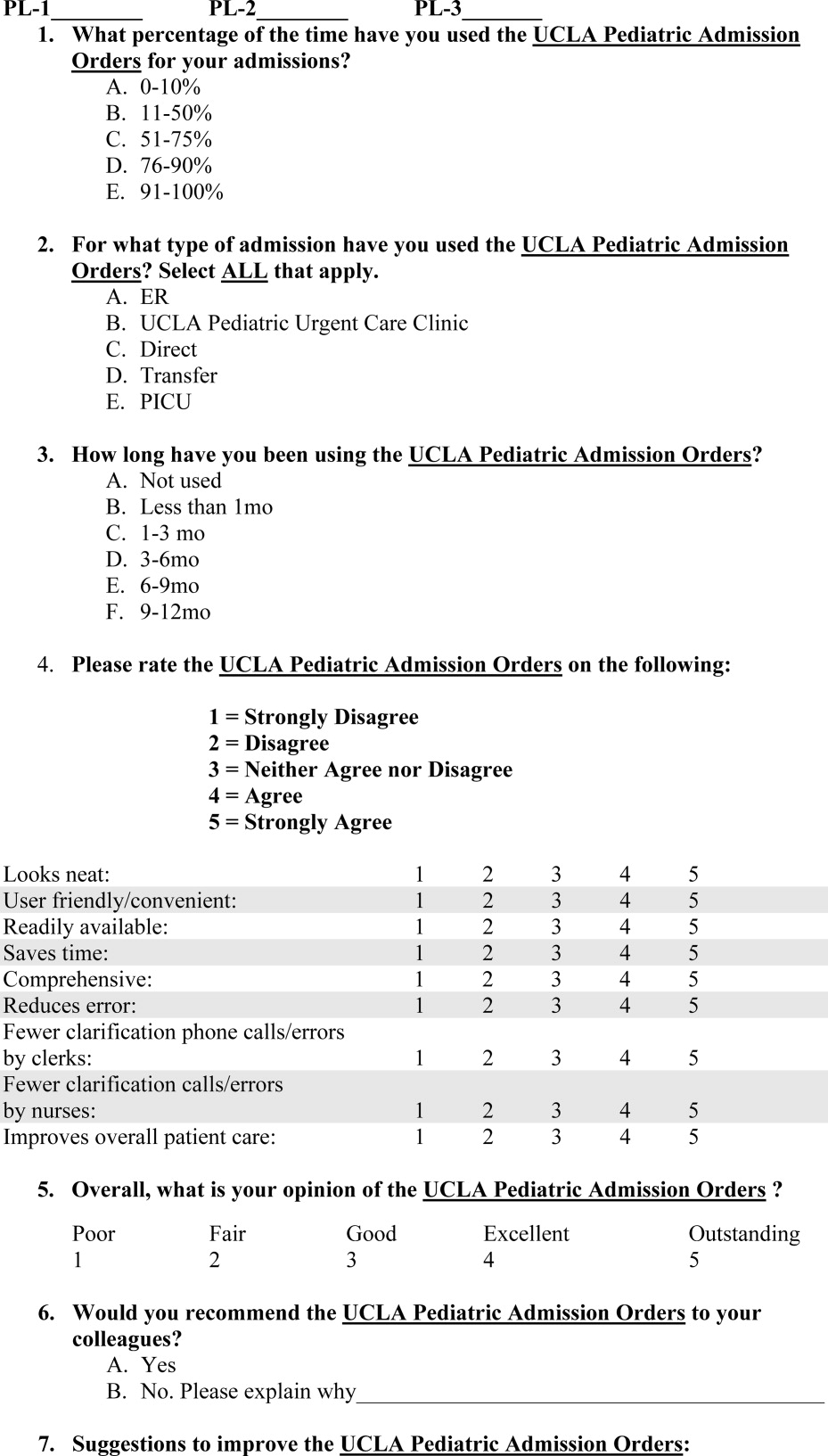

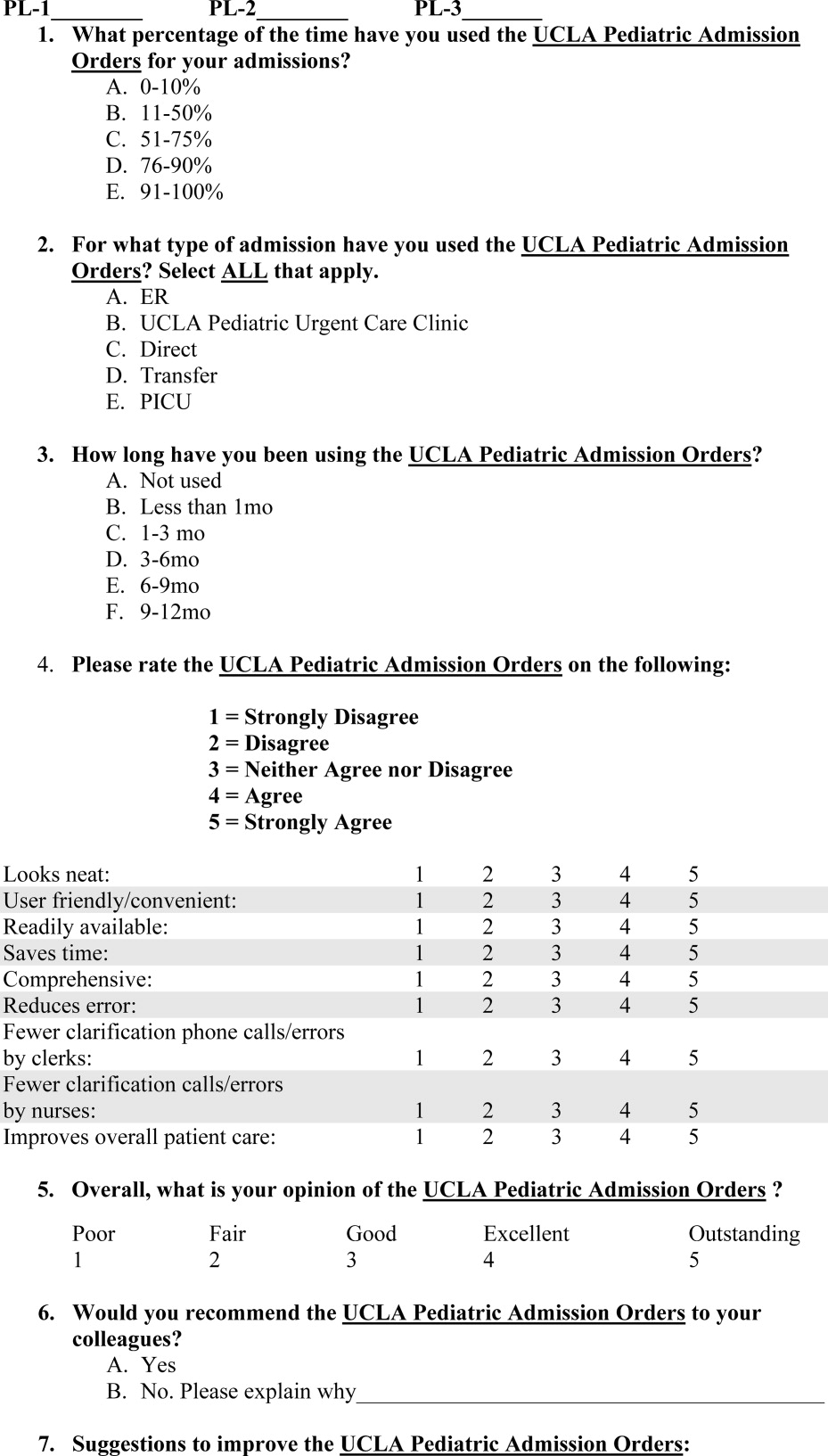

As part of a larger quality improvement initiative at our institution, a multidisciplinary team of pediatric and internal medicine healthcare providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, case managers, social workers, child life specialists), as well as parents and patients, developed an “ideal state” with this transition and a consensus-based conceptual framework of key patient and institutional determinants of a formal inpatient transition initiative for children with chronic conditions within a children’s hospital (Figure).

Institutional Context and Factors Influencing Inpatient Transitions

The following hospital characteristics were assessed: administrative structure (free-standing, hospital-within-hospital, or “free-leaning,” ie, separate physical structure but same administrative structure as a general hospital), urban versus rural, academic versus nonacademic, presence of an inpatient adolescent unit, presence of subspecialty admitting services, and providers with med–peds or family medicine training. The following provider group characteristics were assessed: number of full-time equivalents (FTEs), scope of practice (inpatient only, combination inpatient/outpatient), proportion of providers at a “senior” level (ie, at least 7 years posttraining or at an associate professor rank), estimated number of discharges per week, and proportion of patients cared for without resident physicians.

Inpatient Transition Initiative

Each institution was categorized as having or not having an inpatient transition initiative by whether they indicated having either (1) an institutional leader of the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented inpatient settings or (2) an inpatient transition process, for which “process” was defined as “a standard, organized, and predictable set of transition activities that may or may not be documented, but the steps are generally agreed upon.”

Specific Inpatient Transition Activities

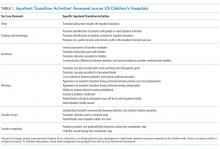

Respondents indicated whether 22 activities occurred consistently, defined as at least 50% of the time. To facilitate description, activities were grouped into categories using the labels from the Six Core Elements framework3 (Table 1): Policy, Tracking and Monitoring, Readiness, Planning, Transfer of Care, and Transfer Completion. Respondents were also asked whether outpatient pediatric-adult transition activities existed at their institution and whether they were linked to inpatient transition activities.

Data Collection

After verifying contact information, respondents received an advanced priming phone call followed by a mailed request to participate with a printed uniform resource locator (URL) to the web survey. Two email reminders containing the URL were sent to nonresponders at 5 and 10 days after the initial mailing. Remaining nonresponders then received a reminder phone call, followed by a mailed paper copy of the survey questionnaire to be completed by hand approximately 2 weeks after the last emailed request. The survey was administered using the Qualtrics web survey platform (www.qualtrics.com). Data collection occurred between January 2016 and July 2016. Participants received a $20 incentive.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized the current state of inpatient transition at general pediatrics services across US children’s hospitals. Exploratory factor analysis assessed whether individual activities were sufficiently correlated to allow grouping items and constructing scales. Differences in institutional or respondent characteristics between hospitals that did and did not report having an inpatient initiative were compared using t tests for continuous data. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data because some cell sizes were ≤5. Bivariate logistic regression quantified associations between presence versus absence of specific transition activities and presence versus absence of an inpatient transition initiative. Analyses were completed in STATA (SE version 14.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas). The institutional review board at our institution approved this study.

RESULTS

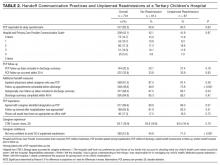

Responses were received from 96 of 195 children’s hospitals (49.2% response rate). Responding institution characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Free-standing children’s hospitals made up just over one-third of the sample (36%), while the remaining were free-leaning (22%) or hospital-within-hospital (43%). Most children’s hospitals (58%) did not have a specific adult-oriented hospital identified to receive transitioning patients. Slightly more than 10% had an inpatient adolescent unit. The majority of institutions were academic medical centers (78%) in urban locations (88%). Respondents represented small (<5 FTE, 21%), medium (6-10 FTE, 36%), and large provider groups (11+ FTE, 44%). Although 70% of respondents described their groups as “hospitalist only,” meaning providers only practiced inpatient general pediatrics, nearly 30% had providers practicing inpatient and outpatient general pediatrics. Just over 40% of respondents reported having med–peds providers. Pediatric-adult transition processes for outpatient care were present at 45% of institutions.

Transition Activities

Thirty-eight percent of children’s hospitals had an inpatient transition initiative using our study definition—31% by having a set of generally agreed upon activities, 19% by having a leader, and 11% having both. Inpatient transition leaders included pediatric hospitalists (43%), pediatric subspecialists and primary care providers (14% each), med–peds providers (11%), or case managers (7%). Respondent and institutional characteristics were similar at institutions that did and did not have an inpatient transition initiative (Table 2); however, children’s hospitals with inpatient transition initiatives more often had med–peds providers (P = .04). Institutions with pediatric-adult outpatient care transition processes more often had an inpatient initiative (71% and 29%, respectively; P = .001).

Exploratory factor analysis identified 2 groups of well-correlated items, which we grouped into “preparation” and “transfer initiation” scales (supplementary Appendix). The preparation scale was composed of the following 5 items (Cronbach α = 0.84): proactive identification of patients anticipated to need transition, proactive identification of patients overdue for transition, readiness formally assessed, timing discussed with family, and patient and/or family informed that the next stay would be at the adult facility. The transfer initiation scale comprised the following 6 items (Cronbach α = 0.72): transition education provided to families, primary care–subspecialist agreement on timing, subspecialist–subspecialist agreement on timing, patient decision-making ability established, adult facility tour, and standardized handoff communication between healthcare providers. While these items were analyzed only in this scale, other activities were analyzed as independent variables. In this analysis, 40.9% of institutions had a preparation scale score of 0 (no items performed), while 13% had all 5 items performed. Transfer initiation scale scores ranged from 0 (47%) to 6 (2%).

Specific activities varied widely across institutions, and none of the activities occurred at a majority of children’s hospitals (Table 3). Only 11% of children’s hospital transition policies referenced transitions of inpatient care. The activity most commonly reported across children’s hospitals was addressing potential insurance problems (41%). The least common inpatient transition activities were having child life consult during the first adult hospital stay (6%) or having a system to track and monitor youth in the inpatient transition process (2%). Transition processes and policies were relatively new among institutions that had them—average years an inpatient transition process had been in place was 1.2 (SD 0.4), and average years with a transition policy, including inpatient care, was 1.3 (SD 0.4).

Transition Activities at Hospitals With and Without an Inpatient Transition Initiative

Most activities assessed in this study (both scales plus 5 of 11 individual activities) were significantly more common in children’s hospitals with an inpatient transition initiative (Table 3). The most common activity was addressing potential insurance problems (46%), and the least common activity was having a system to track and monitor youth in the inpatient transition process (3%). The majority of institutions without an inpatient transition initiative (53%) performed 0 transfer initiation scale items. Large effect sizes between hospitals with and without a transition initiative were observed for use of a checklist to complete tasks (odds ratio [OR] 9.6, P = .04) and creation of a transition care plan (OR 9.0, P = .008). Of the 6 activities performed at similarly low frequencies at institutions with and without an initiative, half involved transition planning, the essential step after readiness but before actual transfer of care.

DISCUSSION

We conducted the first national survey describing the policies and procedures of the transition of general inpatient care from children’s to adult-oriented hospitals for youth and young adults with chronic conditions. Our main findings demonstrate that a relatively small number of general inpatient services at children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd this transition, and a minority have a specific adult hospital identified to receive their patients. Even among institutions with inpatient transition initiatives, there is wide variability in the performance of activities to facilitate transitioning out of US children’s hospitals. In these institutions, performance seems to be more lacking in later links of the transition chain. Results from this work can serve as a baseline and identify organizational needs and opportunities for future work.

Children’s hospital general services with and without an inpatient pediatric-adult transition initiative had largely similar characteristics; however, the limited sample size may lack power to detect some differences. Perhaps not surprisingly, having med–peds providers and outpatient transition processes were the characteristics most associated with having an inpatient pediatric-adult transition initiative. The observation that over 70% of hospitals with an outpatient process had an inpatient transition leader or dedicated process makes us optimistic that as general transition efforts expand, more robust inpatient transition activities may be achievable.

We appreciate that the most appropriate location to care for hospitalized young adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions is neither known nor answered with this study. Both options face challenges—adult-oriented hospitals may not be equipped to care for adult manifestations of childhood-onset conditions,14,15 while children’s hospitals may lack the resources and expertise to provide comprehensive care to adults.7 Although hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions are admitted to children’s compared with adult hospitals,12,13,16 important confounders such as severity of illness could explain why adult-aged patients may both remain in children’s hospitals at older ages and simultaneously have worse outcomes than peers. Regardless, at some point, transitioning care into an adult-oriented hospital may be in patients’ best interests. If so, families and providers need guidance on (1) the important aspects of this transition and (2) how to effectively implement the transition.

Because the most important inpatient transition care activities are not empirically known, we designed our survey to assess a broad set of desirable activities emerging from our multidisciplinary quality improvement work. We mapped these activities to the categories used by the Six Core Elements framework.3 Addressing insurance issues was one of the most commonly reported activities, although still fewer than 50% of hospitals reported addressing these problems. It was notable that the majority of institutions without a transition initiative performed none of the transfer initiation scale items. In addition, 2 features of transition efforts highlighted by advocates nationally—use of a checklist and creation of a transition care plan— were 9 times more likely when sites had transition initiatives. Such findings may be motivating for institutions that are considering establishing a transition initiative. Overall, we were not surprised with hospitals’ relatively low performance across most transition activities because only about 40% of US families of children with special healthcare needs report receiving the general services they need to transition to adult healthcare.17

We suspect that a number of the studied inpatient transition activities may be uncommon for structural reasons. For example, having child life consultation during an initial adult stay was rare. In fact, we observed post hoc that it occurred only in hospital-within-hospital systems, an expected finding because adult-only facilities are unlikely to have child life personnel. Other barriers, however, are less obviously structural. Almost no respondents indicated providing a tour of an adult facility, which was true whether the children’s hospital was free-standing or hospital-within-hospital. Given that hospitals with med–peds providers more often had inpatient transition initiatives, it would be interesting to examine whether institutions with med–peds training programs are able to overcome more of these barriers because of the bridges inherently created between departments even when at physically separated sites.

Having a system to track and/or monitor youth going through the transition process was also uncommon. This presumably valuable activity is one of the Six Core Elements3 and is reminiscent of population management strategies increasingly common in primary care.18 Pediatric hospitalists might benefit from adopting a similar philosophy for certain patient populations. Determining whether this activity would be most appropriately managed by inpatient providers versus being integrated into a comprehensive tracking and/or monitoring strategy (ie, inpatient care plus primary care, subspecialty care, school, employment, insurance, etc.) is worth continued consideration.

Although the activities we studied spanned many important dimensions, the most important transition activities in any given context may differ based on institutional resources and those of nearby adult healthcare providers.16 For example, an activity may be absent at a children’s hospital because it is already readily handled in primary care within that health system. Understanding how local resources and patient needs influence the relationship between transition activities and outcomes is an important next step in this line of work. Such research could inform how institutions adapt effective transition activities (eg, developing care plans) to most efficiently meet the needs of their patients and families.

Our findings align with and advance the limited work published on this aspect of transition. A systematic literature review of general healthcare transition interventions found that meeting adult providers prior to transitioning out of the pediatric system was associated with less concern about admission to the adult hospital floor.9 Formally recognizing inpatient care as a part of a comprehensive approach to transition may help adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions progress into adult-oriented hospitals. Inpatient and outpatient providers can educate one another on critical aspects of transition that span across settings. The Cystic Fibrosis (CF) Foundation has established a set of processes to facilitate the transition to adult care and specifically articulates the transfer to adult inpatient settings.19,20 Perhaps as a result, CF is also one of few conditions with fewer adult patients being admitted to children’s hospitals7 despite the increasing number of adults living with the condition.19 Adapting the CF Foundation approach to other chronic conditions may be an effective approach.

Our study has important limitations. Most pertinently, the list of transition activities was developed at a single institution. Although drawing on accepted national guidelines and a diverse local quality improvement group, our listed activities could not be exhaustive. Care plan development and posttransition follow-up activities may benefit from ongoing development in subsequent work. Continuing to identify and integrate approaches taken at other children’s hospitals will also be informative. For example, some children’s hospitals have introduced adult medicine consultative services to focus on transition, attending children’s hospital safety rounds, and sharing standard care protocols for adult patients still cared for in pediatric settings (eg, stroke and myocardial infarction).16

In addition, our findings are limited to generalist teams at children’s hospitals and may not be applicable to inpatient subspecialty services. We could not compare differences in respondents versus nonrespondents to determine whether important selection bias exists. Respondent answers could not be verified. Despite our attempt to identify the most informed respondent at each hospital, responses may have differed with other hospital respondents. We used a novel instrument with unknown psychometric properties. Our data provide only the children’s hospital perspective, and perspectives of others (eg, families, primary care pediatricians or internists, subspecialists, etc.) will be valuable to explore in subsequent research. Subsequent research should investigate the relative importance and feasibility of specific inpatient transition activities, ideal timing, as well as the expected outcomes of high-quality inpatient transition. An important question for future work is to identify which patients are most likely to benefit by having inpatient care as part of their transition plan.

CONCLUSIONS

Nevertheless, the clinical and health services implications of this facet of transition appear to be substantial.16 To meet the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) core outcome for children with special healthcare needs to receive “the services necessary to make transitions to adult healthcare,”21 development, validation, and implementation of effective inpatient-specific transition activities and a set of measurable processes and outcomes are needed. A key direction for the healthcare transitions field, with respect to inpatient care, is to determine the activities most effective at improving relevant patient and family outcomes. Ultimately, we advocate that the transition of inpatient care be integrated into comprehensive approaches to transitional care.

Disclosure: The project described was supported in part by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The project was also supported by the University of Wisconsin Departments of Pediatrics and Medicine. The authors have no financial or other relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

1. Vaks Y, Bensen R, Steidtmann D, et al. Better health, less spending: Redesigning the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare for youth with chronic illness. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4(1):57-68.

2. Bensen R, Steidtmann D, Vaks Y. A Triple Aim Approach to Transition from Pediatric to Adult Health Care for Youth with Special Health Care Needs. Palo Alto, CA: Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health; 2014.

3. Got Transition. Center for Health Care Transition Improvement 2016; http://www.gottransition.org/. Accessed April 4, 2016.

4. McPheeters M, Davis AM, Taylor JL, Brown RF, Potter SA, Epstein RA. Transition Care for Children with Special Health Needs. Technical Brief No. 15. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

5. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians, Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group, Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):182-200.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1304-1306.

7. Goodman DM, Hall M, Levin A, et al. Adults with chronic health conditions originating in childhood: inpatient experience in children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):5-13.

8. Goodman DM, Mendez E, Throop C, Ogata ES. Adult survivors of pediatric illness: the impact on pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):583-589.

9. Bloom SR, Kuhlthau K, Van Cleave J, Knapp AA, Newacheck P, Perrin JM. Health care transition for youth with special health care needs. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):213-219.

10. Fair C, Cuttance J, Sharma N, et al. International and Interdisciplinary Identification of Health Care Transition Outcomes. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(3):205-211.

11. Samuel SM, Nettel-Aguirre A, Soo A, Hemmelgarn B, Tonelli M, Foster B. Avoidable hospitalizations in youth with kidney failure after transfer to or with only adult care. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e993-e1000.

12. Okumura MJ, Campbell AD, Nasr SZ, Davis MM. Inpatient health care use among adult survivors of chronic childhood illnesses in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(10):1054-1060.

13. Edwards JD, Houtrow AJ, Vasilevskis EE, Dudley RA, Okumura MJ. Multi-institutional profile of adults admitted to pediatric intensive care units. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):436-443.

14. Peter NG, Forke CM, Ginsburg KR, Schwarz DF. Transition from pediatric to adult care: internists’ perspectives. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):417-423.

15. Okumura MJ, Heisler M, Davis MM, Cabana MD, Demonner S, Kerr EA. Comfort of general internists and general pediatricians in providing care for young adults with chronic illnesses of childhood. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1621-1627.

16. Kinnear B, O’Toole JK. Care of Adults in Children’s Hospitals: Acknowledging the Aging Elephant in the Room. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(12):1081-1082.

17. McManus MA, Pollack LR, Cooley WC, et al. Current status of transition preparation among youth with special needs in the United States. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1090-1097.

18. Kelleher KJ, Cooper J, Deans K, et al. Cost saving and quality of care in a pediatric accountable care organization. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e582-e589.

19. Tuchman LK, Schwartz LA, Sawicki GS, Britto MT. Cystic fibrosis and transition to adult medical care. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):566-573.

20. Yankaskas JR, Marshall BC, Sufian B, Simon RH, Rodman D. Cystic fibrosis adult care: consensus conference report. Chest. 2004;125(1 Suppl):1S-39S.

21. CSHCN Core System Outcomes: Goals for a System of Care. The National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs Chartbook 2009-2010. http://mchb.hrsa.gov/cshcn0910/core/co.html Accessed November 30, 2016.

Over 90% of children with chronic diseases now survive into adulthood.1,2 Clinical advances overcoming diseases previously fatal in childhood create new challenges for health systems with limited capacity to manage young adults with complicated and unfamiliar childhood-onset conditions. Consequently, improving the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented care has become a national priority.

Although major pediatric-adult transition initiatives—such as the Six Core Elements Framework,3 a technical brief from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,4 and joint statements from major medical societies5,6—outline key transition recommendations generally and for outpatients, they contain limited or no guidance specifically devoted to transitioning inpatient hospital care from pediatric to adult-oriented settings. Key unknowns include whether, when, and how to transition inpatient care from children’s to nonchildren’s hospitals and how this can be integrated into comprehensive youth-adult transition care.

Nevertheless, the number of discharges of 18- to 21-year-old patients with chronic conditions admitted to children’s hospitals is increasing at a faster rate than discharges of other age groups,7 suggesting both that the population is growing in size and that there are important barriers to transitioning these patients into nonchildren’s hospital settings. Spending on adult patients 18 years or older admitted to children’s hospitals has grown to $1 billion annually.8 Hospitalizations are a commonly proposed outcome measure of pediatric-adult transition work.1,9,10 For example, higher rates of avoidable hospitalizations during early adulthood have been observed for 15- to 22-year-olds with kidney failure cared for exclusively in adult-oriented facilities and during the years immediately after transfer to adult care.11

While research is beginning to describe outcomes of adult-aged patients with childhood-onset chronic conditions admitted to children’s hospitals,7,12,13 there has been no comprehensive description of efforts within children’s hospitals to transition such patients into adult-oriented inpatient settings. This information is necessary to outline institutional needs, delineate opportunities for improvement, and help clinicians strategically organize services for patients requiring this transition.

We sought to characterize the current state of the transition from pediatric- to adult-oriented inpatient care across general pediatric inpatient services at US children’s hospitals. We hypothesized that only a limited and inconsistent set of activities would be practiced. We also hypothesized that institutions having formal outpatient transition processes or providers with specialization to care for this age group, such as dual-trained internal medicine–pediatrics (med–peds) physicians, would report performing more activities.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, Participants

We conducted a national survey of leaders of inpatient general pediatrics services at US children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016. Hospitals were identified using the online Children’s Hospital Association directory. Hospitals without inpatient general pediatrics services (eg, rehabilitation or subspecialty-only facilities) were excluded.

We identified a single respondent from each of the 195 remaining children’s hospitals using a structured protocol. Phone numbers and e-mail addresses of potential respondents were gathered from hospital or medical school directories. Following a standard script, study team members contacted potential respondents to describe the purpose of the study and to confirm their contact information. Hospitals were also allowed to designate a different individual with more specific expertise to participate, when relevant (eg, specific faculty member leading a related quality improvement initiative). The goal was to identify a leader of inpatient care with the most knowledge of institutional practices related to the transition to adult inpatient care. Examples of respondent roles included director of inpatient pediatrics, chief of hospital medicine or general pediatrics, medical director, and similar titles.

Survey Elements

As part of a larger quality improvement initiative at our institution, a multidisciplinary team of pediatric and internal medicine healthcare providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, case managers, social workers, child life specialists), as well as parents and patients, developed an “ideal state” with this transition and a consensus-based conceptual framework of key patient and institutional determinants of a formal inpatient transition initiative for children with chronic conditions within a children’s hospital (Figure).

Institutional Context and Factors Influencing Inpatient Transitions

The following hospital characteristics were assessed: administrative structure (free-standing, hospital-within-hospital, or “free-leaning,” ie, separate physical structure but same administrative structure as a general hospital), urban versus rural, academic versus nonacademic, presence of an inpatient adolescent unit, presence of subspecialty admitting services, and providers with med–peds or family medicine training. The following provider group characteristics were assessed: number of full-time equivalents (FTEs), scope of practice (inpatient only, combination inpatient/outpatient), proportion of providers at a “senior” level (ie, at least 7 years posttraining or at an associate professor rank), estimated number of discharges per week, and proportion of patients cared for without resident physicians.

Inpatient Transition Initiative

Each institution was categorized as having or not having an inpatient transition initiative by whether they indicated having either (1) an institutional leader of the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented inpatient settings or (2) an inpatient transition process, for which “process” was defined as “a standard, organized, and predictable set of transition activities that may or may not be documented, but the steps are generally agreed upon.”

Specific Inpatient Transition Activities

Respondents indicated whether 22 activities occurred consistently, defined as at least 50% of the time. To facilitate description, activities were grouped into categories using the labels from the Six Core Elements framework3 (Table 1): Policy, Tracking and Monitoring, Readiness, Planning, Transfer of Care, and Transfer Completion. Respondents were also asked whether outpatient pediatric-adult transition activities existed at their institution and whether they were linked to inpatient transition activities.

Data Collection

After verifying contact information, respondents received an advanced priming phone call followed by a mailed request to participate with a printed uniform resource locator (URL) to the web survey. Two email reminders containing the URL were sent to nonresponders at 5 and 10 days after the initial mailing. Remaining nonresponders then received a reminder phone call, followed by a mailed paper copy of the survey questionnaire to be completed by hand approximately 2 weeks after the last emailed request. The survey was administered using the Qualtrics web survey platform (www.qualtrics.com). Data collection occurred between January 2016 and July 2016. Participants received a $20 incentive.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized the current state of inpatient transition at general pediatrics services across US children’s hospitals. Exploratory factor analysis assessed whether individual activities were sufficiently correlated to allow grouping items and constructing scales. Differences in institutional or respondent characteristics between hospitals that did and did not report having an inpatient initiative were compared using t tests for continuous data. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data because some cell sizes were ≤5. Bivariate logistic regression quantified associations between presence versus absence of specific transition activities and presence versus absence of an inpatient transition initiative. Analyses were completed in STATA (SE version 14.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas). The institutional review board at our institution approved this study.

RESULTS

Responses were received from 96 of 195 children’s hospitals (49.2% response rate). Responding institution characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Free-standing children’s hospitals made up just over one-third of the sample (36%), while the remaining were free-leaning (22%) or hospital-within-hospital (43%). Most children’s hospitals (58%) did not have a specific adult-oriented hospital identified to receive transitioning patients. Slightly more than 10% had an inpatient adolescent unit. The majority of institutions were academic medical centers (78%) in urban locations (88%). Respondents represented small (<5 FTE, 21%), medium (6-10 FTE, 36%), and large provider groups (11+ FTE, 44%). Although 70% of respondents described their groups as “hospitalist only,” meaning providers only practiced inpatient general pediatrics, nearly 30% had providers practicing inpatient and outpatient general pediatrics. Just over 40% of respondents reported having med–peds providers. Pediatric-adult transition processes for outpatient care were present at 45% of institutions.

Transition Activities

Thirty-eight percent of children’s hospitals had an inpatient transition initiative using our study definition—31% by having a set of generally agreed upon activities, 19% by having a leader, and 11% having both. Inpatient transition leaders included pediatric hospitalists (43%), pediatric subspecialists and primary care providers (14% each), med–peds providers (11%), or case managers (7%). Respondent and institutional characteristics were similar at institutions that did and did not have an inpatient transition initiative (Table 2); however, children’s hospitals with inpatient transition initiatives more often had med–peds providers (P = .04). Institutions with pediatric-adult outpatient care transition processes more often had an inpatient initiative (71% and 29%, respectively; P = .001).

Exploratory factor analysis identified 2 groups of well-correlated items, which we grouped into “preparation” and “transfer initiation” scales (supplementary Appendix). The preparation scale was composed of the following 5 items (Cronbach α = 0.84): proactive identification of patients anticipated to need transition, proactive identification of patients overdue for transition, readiness formally assessed, timing discussed with family, and patient and/or family informed that the next stay would be at the adult facility. The transfer initiation scale comprised the following 6 items (Cronbach α = 0.72): transition education provided to families, primary care–subspecialist agreement on timing, subspecialist–subspecialist agreement on timing, patient decision-making ability established, adult facility tour, and standardized handoff communication between healthcare providers. While these items were analyzed only in this scale, other activities were analyzed as independent variables. In this analysis, 40.9% of institutions had a preparation scale score of 0 (no items performed), while 13% had all 5 items performed. Transfer initiation scale scores ranged from 0 (47%) to 6 (2%).

Specific activities varied widely across institutions, and none of the activities occurred at a majority of children’s hospitals (Table 3). Only 11% of children’s hospital transition policies referenced transitions of inpatient care. The activity most commonly reported across children’s hospitals was addressing potential insurance problems (41%). The least common inpatient transition activities were having child life consult during the first adult hospital stay (6%) or having a system to track and monitor youth in the inpatient transition process (2%). Transition processes and policies were relatively new among institutions that had them—average years an inpatient transition process had been in place was 1.2 (SD 0.4), and average years with a transition policy, including inpatient care, was 1.3 (SD 0.4).

Transition Activities at Hospitals With and Without an Inpatient Transition Initiative

Most activities assessed in this study (both scales plus 5 of 11 individual activities) were significantly more common in children’s hospitals with an inpatient transition initiative (Table 3). The most common activity was addressing potential insurance problems (46%), and the least common activity was having a system to track and monitor youth in the inpatient transition process (3%). The majority of institutions without an inpatient transition initiative (53%) performed 0 transfer initiation scale items. Large effect sizes between hospitals with and without a transition initiative were observed for use of a checklist to complete tasks (odds ratio [OR] 9.6, P = .04) and creation of a transition care plan (OR 9.0, P = .008). Of the 6 activities performed at similarly low frequencies at institutions with and without an initiative, half involved transition planning, the essential step after readiness but before actual transfer of care.

DISCUSSION

We conducted the first national survey describing the policies and procedures of the transition of general inpatient care from children’s to adult-oriented hospitals for youth and young adults with chronic conditions. Our main findings demonstrate that a relatively small number of general inpatient services at children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd this transition, and a minority have a specific adult hospital identified to receive their patients. Even among institutions with inpatient transition initiatives, there is wide variability in the performance of activities to facilitate transitioning out of US children’s hospitals. In these institutions, performance seems to be more lacking in later links of the transition chain. Results from this work can serve as a baseline and identify organizational needs and opportunities for future work.

Children’s hospital general services with and without an inpatient pediatric-adult transition initiative had largely similar characteristics; however, the limited sample size may lack power to detect some differences. Perhaps not surprisingly, having med–peds providers and outpatient transition processes were the characteristics most associated with having an inpatient pediatric-adult transition initiative. The observation that over 70% of hospitals with an outpatient process had an inpatient transition leader or dedicated process makes us optimistic that as general transition efforts expand, more robust inpatient transition activities may be achievable.

We appreciate that the most appropriate location to care for hospitalized young adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions is neither known nor answered with this study. Both options face challenges—adult-oriented hospitals may not be equipped to care for adult manifestations of childhood-onset conditions,14,15 while children’s hospitals may lack the resources and expertise to provide comprehensive care to adults.7 Although hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions are admitted to children’s compared with adult hospitals,12,13,16 important confounders such as severity of illness could explain why adult-aged patients may both remain in children’s hospitals at older ages and simultaneously have worse outcomes than peers. Regardless, at some point, transitioning care into an adult-oriented hospital may be in patients’ best interests. If so, families and providers need guidance on (1) the important aspects of this transition and (2) how to effectively implement the transition.

Because the most important inpatient transition care activities are not empirically known, we designed our survey to assess a broad set of desirable activities emerging from our multidisciplinary quality improvement work. We mapped these activities to the categories used by the Six Core Elements framework.3 Addressing insurance issues was one of the most commonly reported activities, although still fewer than 50% of hospitals reported addressing these problems. It was notable that the majority of institutions without a transition initiative performed none of the transfer initiation scale items. In addition, 2 features of transition efforts highlighted by advocates nationally—use of a checklist and creation of a transition care plan— were 9 times more likely when sites had transition initiatives. Such findings may be motivating for institutions that are considering establishing a transition initiative. Overall, we were not surprised with hospitals’ relatively low performance across most transition activities because only about 40% of US families of children with special healthcare needs report receiving the general services they need to transition to adult healthcare.17

We suspect that a number of the studied inpatient transition activities may be uncommon for structural reasons. For example, having child life consultation during an initial adult stay was rare. In fact, we observed post hoc that it occurred only in hospital-within-hospital systems, an expected finding because adult-only facilities are unlikely to have child life personnel. Other barriers, however, are less obviously structural. Almost no respondents indicated providing a tour of an adult facility, which was true whether the children’s hospital was free-standing or hospital-within-hospital. Given that hospitals with med–peds providers more often had inpatient transition initiatives, it would be interesting to examine whether institutions with med–peds training programs are able to overcome more of these barriers because of the bridges inherently created between departments even when at physically separated sites.

Having a system to track and/or monitor youth going through the transition process was also uncommon. This presumably valuable activity is one of the Six Core Elements3 and is reminiscent of population management strategies increasingly common in primary care.18 Pediatric hospitalists might benefit from adopting a similar philosophy for certain patient populations. Determining whether this activity would be most appropriately managed by inpatient providers versus being integrated into a comprehensive tracking and/or monitoring strategy (ie, inpatient care plus primary care, subspecialty care, school, employment, insurance, etc.) is worth continued consideration.

Although the activities we studied spanned many important dimensions, the most important transition activities in any given context may differ based on institutional resources and those of nearby adult healthcare providers.16 For example, an activity may be absent at a children’s hospital because it is already readily handled in primary care within that health system. Understanding how local resources and patient needs influence the relationship between transition activities and outcomes is an important next step in this line of work. Such research could inform how institutions adapt effective transition activities (eg, developing care plans) to most efficiently meet the needs of their patients and families.

Our findings align with and advance the limited work published on this aspect of transition. A systematic literature review of general healthcare transition interventions found that meeting adult providers prior to transitioning out of the pediatric system was associated with less concern about admission to the adult hospital floor.9 Formally recognizing inpatient care as a part of a comprehensive approach to transition may help adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions progress into adult-oriented hospitals. Inpatient and outpatient providers can educate one another on critical aspects of transition that span across settings. The Cystic Fibrosis (CF) Foundation has established a set of processes to facilitate the transition to adult care and specifically articulates the transfer to adult inpatient settings.19,20 Perhaps as a result, CF is also one of few conditions with fewer adult patients being admitted to children’s hospitals7 despite the increasing number of adults living with the condition.19 Adapting the CF Foundation approach to other chronic conditions may be an effective approach.

Our study has important limitations. Most pertinently, the list of transition activities was developed at a single institution. Although drawing on accepted national guidelines and a diverse local quality improvement group, our listed activities could not be exhaustive. Care plan development and posttransition follow-up activities may benefit from ongoing development in subsequent work. Continuing to identify and integrate approaches taken at other children’s hospitals will also be informative. For example, some children’s hospitals have introduced adult medicine consultative services to focus on transition, attending children’s hospital safety rounds, and sharing standard care protocols for adult patients still cared for in pediatric settings (eg, stroke and myocardial infarction).16

In addition, our findings are limited to generalist teams at children’s hospitals and may not be applicable to inpatient subspecialty services. We could not compare differences in respondents versus nonrespondents to determine whether important selection bias exists. Respondent answers could not be verified. Despite our attempt to identify the most informed respondent at each hospital, responses may have differed with other hospital respondents. We used a novel instrument with unknown psychometric properties. Our data provide only the children’s hospital perspective, and perspectives of others (eg, families, primary care pediatricians or internists, subspecialists, etc.) will be valuable to explore in subsequent research. Subsequent research should investigate the relative importance and feasibility of specific inpatient transition activities, ideal timing, as well as the expected outcomes of high-quality inpatient transition. An important question for future work is to identify which patients are most likely to benefit by having inpatient care as part of their transition plan.

CONCLUSIONS

Nevertheless, the clinical and health services implications of this facet of transition appear to be substantial.16 To meet the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) core outcome for children with special healthcare needs to receive “the services necessary to make transitions to adult healthcare,”21 development, validation, and implementation of effective inpatient-specific transition activities and a set of measurable processes and outcomes are needed. A key direction for the healthcare transitions field, with respect to inpatient care, is to determine the activities most effective at improving relevant patient and family outcomes. Ultimately, we advocate that the transition of inpatient care be integrated into comprehensive approaches to transitional care.

Disclosure: The project described was supported in part by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The project was also supported by the University of Wisconsin Departments of Pediatrics and Medicine. The authors have no financial or other relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Over 90% of children with chronic diseases now survive into adulthood.1,2 Clinical advances overcoming diseases previously fatal in childhood create new challenges for health systems with limited capacity to manage young adults with complicated and unfamiliar childhood-onset conditions. Consequently, improving the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented care has become a national priority.

Although major pediatric-adult transition initiatives—such as the Six Core Elements Framework,3 a technical brief from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,4 and joint statements from major medical societies5,6—outline key transition recommendations generally and for outpatients, they contain limited or no guidance specifically devoted to transitioning inpatient hospital care from pediatric to adult-oriented settings. Key unknowns include whether, when, and how to transition inpatient care from children’s to nonchildren’s hospitals and how this can be integrated into comprehensive youth-adult transition care.

Nevertheless, the number of discharges of 18- to 21-year-old patients with chronic conditions admitted to children’s hospitals is increasing at a faster rate than discharges of other age groups,7 suggesting both that the population is growing in size and that there are important barriers to transitioning these patients into nonchildren’s hospital settings. Spending on adult patients 18 years or older admitted to children’s hospitals has grown to $1 billion annually.8 Hospitalizations are a commonly proposed outcome measure of pediatric-adult transition work.1,9,10 For example, higher rates of avoidable hospitalizations during early adulthood have been observed for 15- to 22-year-olds with kidney failure cared for exclusively in adult-oriented facilities and during the years immediately after transfer to adult care.11

While research is beginning to describe outcomes of adult-aged patients with childhood-onset chronic conditions admitted to children’s hospitals,7,12,13 there has been no comprehensive description of efforts within children’s hospitals to transition such patients into adult-oriented inpatient settings. This information is necessary to outline institutional needs, delineate opportunities for improvement, and help clinicians strategically organize services for patients requiring this transition.

We sought to characterize the current state of the transition from pediatric- to adult-oriented inpatient care across general pediatric inpatient services at US children’s hospitals. We hypothesized that only a limited and inconsistent set of activities would be practiced. We also hypothesized that institutions having formal outpatient transition processes or providers with specialization to care for this age group, such as dual-trained internal medicine–pediatrics (med–peds) physicians, would report performing more activities.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, Participants

We conducted a national survey of leaders of inpatient general pediatrics services at US children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016. Hospitals were identified using the online Children’s Hospital Association directory. Hospitals without inpatient general pediatrics services (eg, rehabilitation or subspecialty-only facilities) were excluded.

We identified a single respondent from each of the 195 remaining children’s hospitals using a structured protocol. Phone numbers and e-mail addresses of potential respondents were gathered from hospital or medical school directories. Following a standard script, study team members contacted potential respondents to describe the purpose of the study and to confirm their contact information. Hospitals were also allowed to designate a different individual with more specific expertise to participate, when relevant (eg, specific faculty member leading a related quality improvement initiative). The goal was to identify a leader of inpatient care with the most knowledge of institutional practices related to the transition to adult inpatient care. Examples of respondent roles included director of inpatient pediatrics, chief of hospital medicine or general pediatrics, medical director, and similar titles.

Survey Elements

As part of a larger quality improvement initiative at our institution, a multidisciplinary team of pediatric and internal medicine healthcare providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, case managers, social workers, child life specialists), as well as parents and patients, developed an “ideal state” with this transition and a consensus-based conceptual framework of key patient and institutional determinants of a formal inpatient transition initiative for children with chronic conditions within a children’s hospital (Figure).

Institutional Context and Factors Influencing Inpatient Transitions

The following hospital characteristics were assessed: administrative structure (free-standing, hospital-within-hospital, or “free-leaning,” ie, separate physical structure but same administrative structure as a general hospital), urban versus rural, academic versus nonacademic, presence of an inpatient adolescent unit, presence of subspecialty admitting services, and providers with med–peds or family medicine training. The following provider group characteristics were assessed: number of full-time equivalents (FTEs), scope of practice (inpatient only, combination inpatient/outpatient), proportion of providers at a “senior” level (ie, at least 7 years posttraining or at an associate professor rank), estimated number of discharges per week, and proportion of patients cared for without resident physicians.

Inpatient Transition Initiative

Each institution was categorized as having or not having an inpatient transition initiative by whether they indicated having either (1) an institutional leader of the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented inpatient settings or (2) an inpatient transition process, for which “process” was defined as “a standard, organized, and predictable set of transition activities that may or may not be documented, but the steps are generally agreed upon.”

Specific Inpatient Transition Activities

Respondents indicated whether 22 activities occurred consistently, defined as at least 50% of the time. To facilitate description, activities were grouped into categories using the labels from the Six Core Elements framework3 (Table 1): Policy, Tracking and Monitoring, Readiness, Planning, Transfer of Care, and Transfer Completion. Respondents were also asked whether outpatient pediatric-adult transition activities existed at their institution and whether they were linked to inpatient transition activities.

Data Collection

After verifying contact information, respondents received an advanced priming phone call followed by a mailed request to participate with a printed uniform resource locator (URL) to the web survey. Two email reminders containing the URL were sent to nonresponders at 5 and 10 days after the initial mailing. Remaining nonresponders then received a reminder phone call, followed by a mailed paper copy of the survey questionnaire to be completed by hand approximately 2 weeks after the last emailed request. The survey was administered using the Qualtrics web survey platform (www.qualtrics.com). Data collection occurred between January 2016 and July 2016. Participants received a $20 incentive.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized the current state of inpatient transition at general pediatrics services across US children’s hospitals. Exploratory factor analysis assessed whether individual activities were sufficiently correlated to allow grouping items and constructing scales. Differences in institutional or respondent characteristics between hospitals that did and did not report having an inpatient initiative were compared using t tests for continuous data. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data because some cell sizes were ≤5. Bivariate logistic regression quantified associations between presence versus absence of specific transition activities and presence versus absence of an inpatient transition initiative. Analyses were completed in STATA (SE version 14.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas). The institutional review board at our institution approved this study.

RESULTS

Responses were received from 96 of 195 children’s hospitals (49.2% response rate). Responding institution characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Free-standing children’s hospitals made up just over one-third of the sample (36%), while the remaining were free-leaning (22%) or hospital-within-hospital (43%). Most children’s hospitals (58%) did not have a specific adult-oriented hospital identified to receive transitioning patients. Slightly more than 10% had an inpatient adolescent unit. The majority of institutions were academic medical centers (78%) in urban locations (88%). Respondents represented small (<5 FTE, 21%), medium (6-10 FTE, 36%), and large provider groups (11+ FTE, 44%). Although 70% of respondents described their groups as “hospitalist only,” meaning providers only practiced inpatient general pediatrics, nearly 30% had providers practicing inpatient and outpatient general pediatrics. Just over 40% of respondents reported having med–peds providers. Pediatric-adult transition processes for outpatient care were present at 45% of institutions.

Transition Activities

Thirty-eight percent of children’s hospitals had an inpatient transition initiative using our study definition—31% by having a set of generally agreed upon activities, 19% by having a leader, and 11% having both. Inpatient transition leaders included pediatric hospitalists (43%), pediatric subspecialists and primary care providers (14% each), med–peds providers (11%), or case managers (7%). Respondent and institutional characteristics were similar at institutions that did and did not have an inpatient transition initiative (Table 2); however, children’s hospitals with inpatient transition initiatives more often had med–peds providers (P = .04). Institutions with pediatric-adult outpatient care transition processes more often had an inpatient initiative (71% and 29%, respectively; P = .001).

Exploratory factor analysis identified 2 groups of well-correlated items, which we grouped into “preparation” and “transfer initiation” scales (supplementary Appendix). The preparation scale was composed of the following 5 items (Cronbach α = 0.84): proactive identification of patients anticipated to need transition, proactive identification of patients overdue for transition, readiness formally assessed, timing discussed with family, and patient and/or family informed that the next stay would be at the adult facility. The transfer initiation scale comprised the following 6 items (Cronbach α = 0.72): transition education provided to families, primary care–subspecialist agreement on timing, subspecialist–subspecialist agreement on timing, patient decision-making ability established, adult facility tour, and standardized handoff communication between healthcare providers. While these items were analyzed only in this scale, other activities were analyzed as independent variables. In this analysis, 40.9% of institutions had a preparation scale score of 0 (no items performed), while 13% had all 5 items performed. Transfer initiation scale scores ranged from 0 (47%) to 6 (2%).

Specific activities varied widely across institutions, and none of the activities occurred at a majority of children’s hospitals (Table 3). Only 11% of children’s hospital transition policies referenced transitions of inpatient care. The activity most commonly reported across children’s hospitals was addressing potential insurance problems (41%). The least common inpatient transition activities were having child life consult during the first adult hospital stay (6%) or having a system to track and monitor youth in the inpatient transition process (2%). Transition processes and policies were relatively new among institutions that had them—average years an inpatient transition process had been in place was 1.2 (SD 0.4), and average years with a transition policy, including inpatient care, was 1.3 (SD 0.4).

Transition Activities at Hospitals With and Without an Inpatient Transition Initiative

Most activities assessed in this study (both scales plus 5 of 11 individual activities) were significantly more common in children’s hospitals with an inpatient transition initiative (Table 3). The most common activity was addressing potential insurance problems (46%), and the least common activity was having a system to track and monitor youth in the inpatient transition process (3%). The majority of institutions without an inpatient transition initiative (53%) performed 0 transfer initiation scale items. Large effect sizes between hospitals with and without a transition initiative were observed for use of a checklist to complete tasks (odds ratio [OR] 9.6, P = .04) and creation of a transition care plan (OR 9.0, P = .008). Of the 6 activities performed at similarly low frequencies at institutions with and without an initiative, half involved transition planning, the essential step after readiness but before actual transfer of care.

DISCUSSION

We conducted the first national survey describing the policies and procedures of the transition of general inpatient care from children’s to adult-oriented hospitals for youth and young adults with chronic conditions. Our main findings demonstrate that a relatively small number of general inpatient services at children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd this transition, and a minority have a specific adult hospital identified to receive their patients. Even among institutions with inpatient transition initiatives, there is wide variability in the performance of activities to facilitate transitioning out of US children’s hospitals. In these institutions, performance seems to be more lacking in later links of the transition chain. Results from this work can serve as a baseline and identify organizational needs and opportunities for future work.

Children’s hospital general services with and without an inpatient pediatric-adult transition initiative had largely similar characteristics; however, the limited sample size may lack power to detect some differences. Perhaps not surprisingly, having med–peds providers and outpatient transition processes were the characteristics most associated with having an inpatient pediatric-adult transition initiative. The observation that over 70% of hospitals with an outpatient process had an inpatient transition leader or dedicated process makes us optimistic that as general transition efforts expand, more robust inpatient transition activities may be achievable.

We appreciate that the most appropriate location to care for hospitalized young adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions is neither known nor answered with this study. Both options face challenges—adult-oriented hospitals may not be equipped to care for adult manifestations of childhood-onset conditions,14,15 while children’s hospitals may lack the resources and expertise to provide comprehensive care to adults.7 Although hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions are admitted to children’s compared with adult hospitals,12,13,16 important confounders such as severity of illness could explain why adult-aged patients may both remain in children’s hospitals at older ages and simultaneously have worse outcomes than peers. Regardless, at some point, transitioning care into an adult-oriented hospital may be in patients’ best interests. If so, families and providers need guidance on (1) the important aspects of this transition and (2) how to effectively implement the transition.

Because the most important inpatient transition care activities are not empirically known, we designed our survey to assess a broad set of desirable activities emerging from our multidisciplinary quality improvement work. We mapped these activities to the categories used by the Six Core Elements framework.3 Addressing insurance issues was one of the most commonly reported activities, although still fewer than 50% of hospitals reported addressing these problems. It was notable that the majority of institutions without a transition initiative performed none of the transfer initiation scale items. In addition, 2 features of transition efforts highlighted by advocates nationally—use of a checklist and creation of a transition care plan— were 9 times more likely when sites had transition initiatives. Such findings may be motivating for institutions that are considering establishing a transition initiative. Overall, we were not surprised with hospitals’ relatively low performance across most transition activities because only about 40% of US families of children with special healthcare needs report receiving the general services they need to transition to adult healthcare.17

We suspect that a number of the studied inpatient transition activities may be uncommon for structural reasons. For example, having child life consultation during an initial adult stay was rare. In fact, we observed post hoc that it occurred only in hospital-within-hospital systems, an expected finding because adult-only facilities are unlikely to have child life personnel. Other barriers, however, are less obviously structural. Almost no respondents indicated providing a tour of an adult facility, which was true whether the children’s hospital was free-standing or hospital-within-hospital. Given that hospitals with med–peds providers more often had inpatient transition initiatives, it would be interesting to examine whether institutions with med–peds training programs are able to overcome more of these barriers because of the bridges inherently created between departments even when at physically separated sites.

Having a system to track and/or monitor youth going through the transition process was also uncommon. This presumably valuable activity is one of the Six Core Elements3 and is reminiscent of population management strategies increasingly common in primary care.18 Pediatric hospitalists might benefit from adopting a similar philosophy for certain patient populations. Determining whether this activity would be most appropriately managed by inpatient providers versus being integrated into a comprehensive tracking and/or monitoring strategy (ie, inpatient care plus primary care, subspecialty care, school, employment, insurance, etc.) is worth continued consideration.

Although the activities we studied spanned many important dimensions, the most important transition activities in any given context may differ based on institutional resources and those of nearby adult healthcare providers.16 For example, an activity may be absent at a children’s hospital because it is already readily handled in primary care within that health system. Understanding how local resources and patient needs influence the relationship between transition activities and outcomes is an important next step in this line of work. Such research could inform how institutions adapt effective transition activities (eg, developing care plans) to most efficiently meet the needs of their patients and families.