User login

En Coup de Sabre

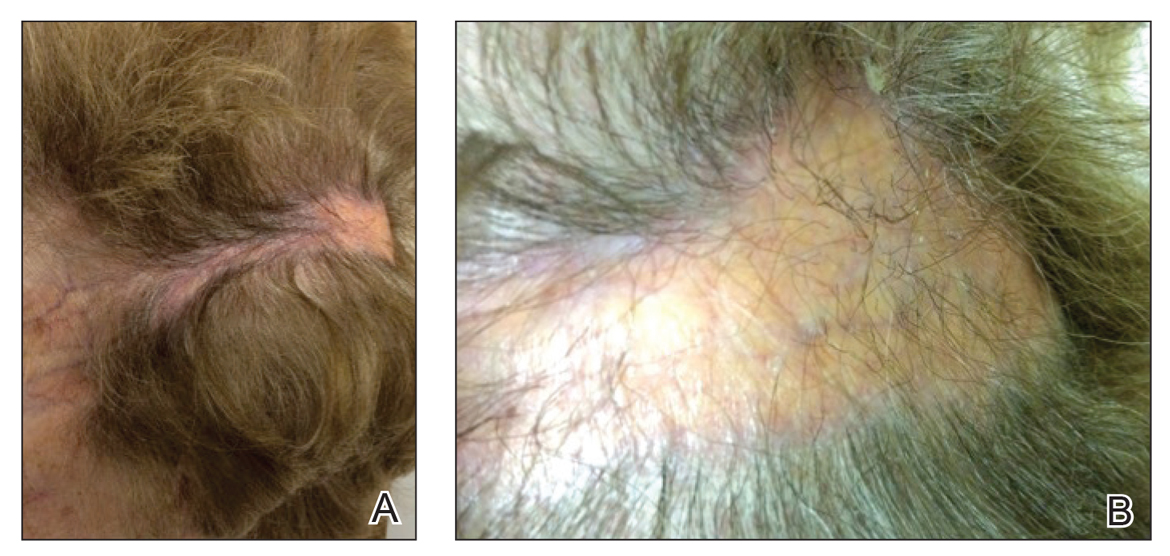

En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a unilateral distribution. The lesional skin first exhibits contraction and stiffness that lead to characteristic fibrotic plaques with associated linear alopecia.1 The pansclerotic plaques are ivory in color with hyperpigmented to violaceous borders extending as a paramedian band on the frontoparietal scalp.2,3 The skin lesions bear resemblance to the stroke of the sabre sword, giving the condition its unique name. Many patients initially present with concerns of frontal scalp alopecia.3 Linear morphea, including the ECDS subtype, is predominantly seen in children and women, usually presenting within the first 2 decades of life.1,4

The differential diagnoses of ECDS include focal dermal hypoplasia, steroid atrophy, localized morphea, and lupus profundus.5 En coup de sabre should be distinguished from progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA)(also known as Parry-Romberg syndrome).6 Progressive hemifacial atrophy presents as unilateral atrophy of the face involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and underlying bone in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.1 Both PHA and ECDS exist on a spectrum of linear scleroderma and may coexist in the same patient.6

There is a strong association with extracutaneous neurologic involvement, including seizures, ocular abnormalities, trigeminal neuralgia, and headache.7-10 One study examining ECDS and PHA demonstrated that 44% (19/43) of patients who underwent central nervous system imaging had abnormal findings.11 The majority of patients had magnetic resonance imaging with or without contrast, computed tomography, or both. The most common findings on T2-weighted images were white matter hyperintensities, mostly in subcortical and periventricular regions. The findings were bilateral in 61% (11/18) of patients and ipsilateral to the lesion in 33% (6/18) of patients.11 We present a case of ECDS masquerading as alopecia in a 77-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 77-year-old white woman presented with a chief concern of hair loss on the scalp that had been present since 12 years of age. During her adult life, the scalp lesion remained unchanged with no associated symptoms. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The patient denied any history of seizure disorders, facial paralysis, or neurologic deficits.

Comment

Etiology and Presentation

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear morphea that involves the frontoparietal scalp and forehead.7,12,13 It manifests as a solitary, linear, fibrous plaque that involves the skin, underlying muscle, and bone.7 Although most cases present with a single lesion, multiple lesions can occur.8 The exact etiology of this disease remains to be determined but is characterized by thickening and hardening of the skin secondary to increased collagen production.7 The incidence of linear morphea ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals and is more prevalent in white patients and women.14 Linear morphea is commonly found in children. Children are more likely to have linear morphea on the face, which can lead to lifelong disfigurement.2 Although the disease peaks in the fourth decade of life for adults, most pediatric cases are diagnosed between 2 and 14 years of age.14-16

Pathogenesis

Clinical and histopathological data suggest that a complex interaction among the vasculature, extracellular matrix, and immune system plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Similar to scleroderma, the CD4 helper T cell may be involved in the fibrotic changes that occur within these lesions.17 Early in the disease process, TH1 and TH17 inflammatory pathways predominate. The late fibrotic changes seen in scleroderma are more associated with a shift to the TH2 inflammatory pathway.17 Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi has been implicated abroad, but a large-scale study confirming Borrelia as a pathologic factor within morphea lesions has not been completed to date.18-20 Some authors believe early lesions of ECDS mimic erythema chronica migrans, with the late lesions resembling acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.20

Histopathology

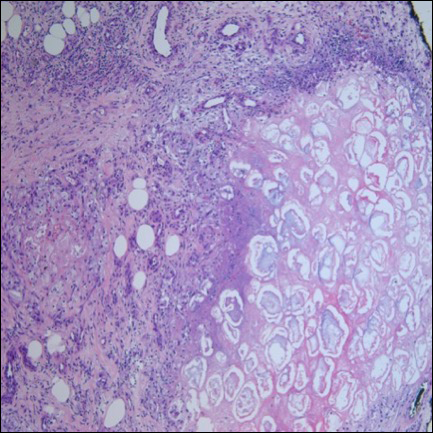

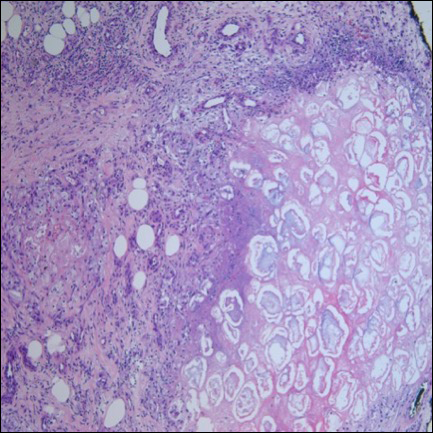

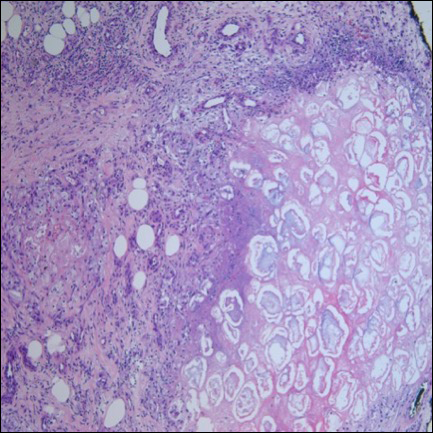

Histopathologic findings of morphea tend to vary depending on the stage of the disease. The 2 stages of morphea can be differentiated by the degree of inflammation present histologically.14,21 The early phase of morphea primarily affects the connective and subcutaneous tissue surrounding eccrine sweat glands.14,21 A dense dermal and subcutaneous perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes is commonly observed.5 Later stages of the disease demonstrate densely packed homogenous collagen with minimal inflammation and loss of eccrine glands and blood vessels.14,21 The adipose tissue is generally replaced by sclerotic collagen, giving the biopsy a squared-off appearance.5,14

Management

En coup de sabre presents a treatment challenge. In active lesions, topical or intralesional corticosteroids are considered treatment of choice.5 Methotrexate has proven useful in the treatment of acute and deep forms of linear morphea. A study examining methotrexate in juvenile localized scleroderma, with the majority of patients having the linear subtype, revealed that methotrexate is both efficacious and well tolerated.22 Other reports in the literature reveal efficacy with the use of intravenous corticosteroids and methotrexate combination therapy for treatment of morphea.23,24 A longitudinal prospective study examining the use of high-dose methotrexate and oral corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma yielded positive results, with patients showing clinical improvement within 2 months of initiation of combination therapy.25 Other treatments include excimer laser; calcipotriene and tacrolimus; and surgical approaches such as autologous fat grafting, grafting with muscle flaps, and tissue inserts.21,26-31 In addition, patients can choose to forego therapy, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the ipsilateral scalp and face predominately in children and women. Neurologic involvement is common and should prompt a comprehensive neurologic workup in patients suspected to have ECDS or PHA. Current treatment recommendations include topical, intralesional, and oral corticosteroids; methotrexate; and surgical grafts. Although ECDS is a rare entity, more intensive research is needed on the exact pathophysiology and effective treatment options that focus on improving the cosmetic outcome in these patients. Cosmesis is the primary concern in patients with ECDS and should be managed early and appropriately to prevent long-term psychological sequelae.

1. Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:62-73.

2. Picket AJ, Carpentieri D, Price H, et al. Early morphea mimicking acquired port-wine stain. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:591-594.

3. Holland KE, Steffes B, Nocton JJ, et al. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre with associated neurologic abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2006;117:132-136.

4. Goh C, Biswas A, Goldberg LJ. Alopecia with perineural lymphocytes: a clue to linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:518-520.

5. Kreuter A. Localized scleroderma. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:135-147.

6. Tolkachjov SN, Patel NG, Tollefson MM. Progressive hemifacial atrophy: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:39.

7. Amaral TN, Marques Neto JF, Lapa AT, et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma en coup de sabre [published online January 27, 2012]. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:719685.

8. Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de sabre morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: a retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:257-263.

9. Zannin ME, Martini G, Athreya BH, et al. Ocular involvement in children with localized scleroderma: a multi-center study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1311-1314.

10. Polcari I, Moon A, Mathes EF, et al. Headaches as a presenting symptom of linear morphea en coup de sabre. Pediatrics. 2014;134:1715-1719.

11. Doolittle DA, Lehman VT, Schwartz KM, et al. CNS imaging findings associated with Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre: correlation to dermatologic and neurologic abnormalities. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:21-34.

12. Pierre-Louis M, Sperling LC, Wilke MS, et al. Distinctive histopathologic findings in linear morphea (en coup de sabre) alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:580-584.

13. Thareja SK, Sadhwani D, Alan Fenske N. En coup de sabre morphea treated with hyaluronic acid filler. Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:823-826.

14. Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

15. Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:385-396.

16. Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW, et al. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:545-550.

17. Kurzinski K, Torok KS. Cytokine profiles in localized scleroderma and relationship to clinical features. Cytokine. 2011;55:157-164.

18. Eisendle K, Grabner T, Zelger B. Morphoea: a manifestation of infection with Borrelia species? Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1189-1198.

19. Gutiérrez-Gómez C, Godínez-Hana AL, García-Hernández M, et al. Lack of IgG antibody seropositivity to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Parry-Romberg syndrome and linear morphea en coup de sabre in Mexico. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:947-951.

20. Miller K, Lehrhoff S, Fischer M, et al. Linear morphea of the forehead (en coup de sabre). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:22.

21. Hanson AH, Fivenson DP, Schapiro B. Linear scleroderma in an adolescent woman treated with methotrexate and excimer laser. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:203-205.

22. Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, et al. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1998-2006.

23. Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate in severe localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:847-852.

24. Weibel L, Sampaio MC, Visentin MT, et al. Evaluation of methotrexate and corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma (morphoea) in children. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1013-1020.

25. Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:286-294.

26. Nisticò SP, Saraceno R, Schipani C, et al. Different applications of monochromatic excimer light in skin diseases. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27:647-654.

27. Zwischenberger BA, Jacobe HT. A systematic review of morphea treatments and therapeutic algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:925-941.

28. Karaaltin MV, Akpinar AC, Baghaki S, et al. Treatment of “en coup de sabre” deformity with adipose-derived regenerative cell-enriched fat graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:103-105.

29. Consorti G, Tieghi R, Clauser LC. Frontal linear scleroderma: long-term result in volumetric restoration of the fronto-orbital area by structural fat grafting. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:263-265.

30. Cavusoglu T, Yazici I, Vargel I, et al. Reconstruction of coup de sabre deformity (linear localized scleroderma) by using galeal frontalis muscle flap and demineralized bone matrix combination. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:257-258.

31. Robitschek J, Wang D, Hall D. Treatment of linear scleroderma “en coup de sabre” with AlloDerm tissue matrix. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:540-541.

En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a unilateral distribution. The lesional skin first exhibits contraction and stiffness that lead to characteristic fibrotic plaques with associated linear alopecia.1 The pansclerotic plaques are ivory in color with hyperpigmented to violaceous borders extending as a paramedian band on the frontoparietal scalp.2,3 The skin lesions bear resemblance to the stroke of the sabre sword, giving the condition its unique name. Many patients initially present with concerns of frontal scalp alopecia.3 Linear morphea, including the ECDS subtype, is predominantly seen in children and women, usually presenting within the first 2 decades of life.1,4

The differential diagnoses of ECDS include focal dermal hypoplasia, steroid atrophy, localized morphea, and lupus profundus.5 En coup de sabre should be distinguished from progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA)(also known as Parry-Romberg syndrome).6 Progressive hemifacial atrophy presents as unilateral atrophy of the face involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and underlying bone in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.1 Both PHA and ECDS exist on a spectrum of linear scleroderma and may coexist in the same patient.6

There is a strong association with extracutaneous neurologic involvement, including seizures, ocular abnormalities, trigeminal neuralgia, and headache.7-10 One study examining ECDS and PHA demonstrated that 44% (19/43) of patients who underwent central nervous system imaging had abnormal findings.11 The majority of patients had magnetic resonance imaging with or without contrast, computed tomography, or both. The most common findings on T2-weighted images were white matter hyperintensities, mostly in subcortical and periventricular regions. The findings were bilateral in 61% (11/18) of patients and ipsilateral to the lesion in 33% (6/18) of patients.11 We present a case of ECDS masquerading as alopecia in a 77-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 77-year-old white woman presented with a chief concern of hair loss on the scalp that had been present since 12 years of age. During her adult life, the scalp lesion remained unchanged with no associated symptoms. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The patient denied any history of seizure disorders, facial paralysis, or neurologic deficits.

Comment

Etiology and Presentation

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear morphea that involves the frontoparietal scalp and forehead.7,12,13 It manifests as a solitary, linear, fibrous plaque that involves the skin, underlying muscle, and bone.7 Although most cases present with a single lesion, multiple lesions can occur.8 The exact etiology of this disease remains to be determined but is characterized by thickening and hardening of the skin secondary to increased collagen production.7 The incidence of linear morphea ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals and is more prevalent in white patients and women.14 Linear morphea is commonly found in children. Children are more likely to have linear morphea on the face, which can lead to lifelong disfigurement.2 Although the disease peaks in the fourth decade of life for adults, most pediatric cases are diagnosed between 2 and 14 years of age.14-16

Pathogenesis

Clinical and histopathological data suggest that a complex interaction among the vasculature, extracellular matrix, and immune system plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Similar to scleroderma, the CD4 helper T cell may be involved in the fibrotic changes that occur within these lesions.17 Early in the disease process, TH1 and TH17 inflammatory pathways predominate. The late fibrotic changes seen in scleroderma are more associated with a shift to the TH2 inflammatory pathway.17 Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi has been implicated abroad, but a large-scale study confirming Borrelia as a pathologic factor within morphea lesions has not been completed to date.18-20 Some authors believe early lesions of ECDS mimic erythema chronica migrans, with the late lesions resembling acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.20

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings of morphea tend to vary depending on the stage of the disease. The 2 stages of morphea can be differentiated by the degree of inflammation present histologically.14,21 The early phase of morphea primarily affects the connective and subcutaneous tissue surrounding eccrine sweat glands.14,21 A dense dermal and subcutaneous perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes is commonly observed.5 Later stages of the disease demonstrate densely packed homogenous collagen with minimal inflammation and loss of eccrine glands and blood vessels.14,21 The adipose tissue is generally replaced by sclerotic collagen, giving the biopsy a squared-off appearance.5,14

Management

En coup de sabre presents a treatment challenge. In active lesions, topical or intralesional corticosteroids are considered treatment of choice.5 Methotrexate has proven useful in the treatment of acute and deep forms of linear morphea. A study examining methotrexate in juvenile localized scleroderma, with the majority of patients having the linear subtype, revealed that methotrexate is both efficacious and well tolerated.22 Other reports in the literature reveal efficacy with the use of intravenous corticosteroids and methotrexate combination therapy for treatment of morphea.23,24 A longitudinal prospective study examining the use of high-dose methotrexate and oral corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma yielded positive results, with patients showing clinical improvement within 2 months of initiation of combination therapy.25 Other treatments include excimer laser; calcipotriene and tacrolimus; and surgical approaches such as autologous fat grafting, grafting with muscle flaps, and tissue inserts.21,26-31 In addition, patients can choose to forego therapy, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the ipsilateral scalp and face predominately in children and women. Neurologic involvement is common and should prompt a comprehensive neurologic workup in patients suspected to have ECDS or PHA. Current treatment recommendations include topical, intralesional, and oral corticosteroids; methotrexate; and surgical grafts. Although ECDS is a rare entity, more intensive research is needed on the exact pathophysiology and effective treatment options that focus on improving the cosmetic outcome in these patients. Cosmesis is the primary concern in patients with ECDS and should be managed early and appropriately to prevent long-term psychological sequelae.

En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a unilateral distribution. The lesional skin first exhibits contraction and stiffness that lead to characteristic fibrotic plaques with associated linear alopecia.1 The pansclerotic plaques are ivory in color with hyperpigmented to violaceous borders extending as a paramedian band on the frontoparietal scalp.2,3 The skin lesions bear resemblance to the stroke of the sabre sword, giving the condition its unique name. Many patients initially present with concerns of frontal scalp alopecia.3 Linear morphea, including the ECDS subtype, is predominantly seen in children and women, usually presenting within the first 2 decades of life.1,4

The differential diagnoses of ECDS include focal dermal hypoplasia, steroid atrophy, localized morphea, and lupus profundus.5 En coup de sabre should be distinguished from progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA)(also known as Parry-Romberg syndrome).6 Progressive hemifacial atrophy presents as unilateral atrophy of the face involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and underlying bone in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.1 Both PHA and ECDS exist on a spectrum of linear scleroderma and may coexist in the same patient.6

There is a strong association with extracutaneous neurologic involvement, including seizures, ocular abnormalities, trigeminal neuralgia, and headache.7-10 One study examining ECDS and PHA demonstrated that 44% (19/43) of patients who underwent central nervous system imaging had abnormal findings.11 The majority of patients had magnetic resonance imaging with or without contrast, computed tomography, or both. The most common findings on T2-weighted images were white matter hyperintensities, mostly in subcortical and periventricular regions. The findings were bilateral in 61% (11/18) of patients and ipsilateral to the lesion in 33% (6/18) of patients.11 We present a case of ECDS masquerading as alopecia in a 77-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 77-year-old white woman presented with a chief concern of hair loss on the scalp that had been present since 12 years of age. During her adult life, the scalp lesion remained unchanged with no associated symptoms. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The patient denied any history of seizure disorders, facial paralysis, or neurologic deficits.

Comment

Etiology and Presentation

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear morphea that involves the frontoparietal scalp and forehead.7,12,13 It manifests as a solitary, linear, fibrous plaque that involves the skin, underlying muscle, and bone.7 Although most cases present with a single lesion, multiple lesions can occur.8 The exact etiology of this disease remains to be determined but is characterized by thickening and hardening of the skin secondary to increased collagen production.7 The incidence of linear morphea ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals and is more prevalent in white patients and women.14 Linear morphea is commonly found in children. Children are more likely to have linear morphea on the face, which can lead to lifelong disfigurement.2 Although the disease peaks in the fourth decade of life for adults, most pediatric cases are diagnosed between 2 and 14 years of age.14-16

Pathogenesis

Clinical and histopathological data suggest that a complex interaction among the vasculature, extracellular matrix, and immune system plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Similar to scleroderma, the CD4 helper T cell may be involved in the fibrotic changes that occur within these lesions.17 Early in the disease process, TH1 and TH17 inflammatory pathways predominate. The late fibrotic changes seen in scleroderma are more associated with a shift to the TH2 inflammatory pathway.17 Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi has been implicated abroad, but a large-scale study confirming Borrelia as a pathologic factor within morphea lesions has not been completed to date.18-20 Some authors believe early lesions of ECDS mimic erythema chronica migrans, with the late lesions resembling acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.20

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings of morphea tend to vary depending on the stage of the disease. The 2 stages of morphea can be differentiated by the degree of inflammation present histologically.14,21 The early phase of morphea primarily affects the connective and subcutaneous tissue surrounding eccrine sweat glands.14,21 A dense dermal and subcutaneous perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes is commonly observed.5 Later stages of the disease demonstrate densely packed homogenous collagen with minimal inflammation and loss of eccrine glands and blood vessels.14,21 The adipose tissue is generally replaced by sclerotic collagen, giving the biopsy a squared-off appearance.5,14

Management

En coup de sabre presents a treatment challenge. In active lesions, topical or intralesional corticosteroids are considered treatment of choice.5 Methotrexate has proven useful in the treatment of acute and deep forms of linear morphea. A study examining methotrexate in juvenile localized scleroderma, with the majority of patients having the linear subtype, revealed that methotrexate is both efficacious and well tolerated.22 Other reports in the literature reveal efficacy with the use of intravenous corticosteroids and methotrexate combination therapy for treatment of morphea.23,24 A longitudinal prospective study examining the use of high-dose methotrexate and oral corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma yielded positive results, with patients showing clinical improvement within 2 months of initiation of combination therapy.25 Other treatments include excimer laser; calcipotriene and tacrolimus; and surgical approaches such as autologous fat grafting, grafting with muscle flaps, and tissue inserts.21,26-31 In addition, patients can choose to forego therapy, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the ipsilateral scalp and face predominately in children and women. Neurologic involvement is common and should prompt a comprehensive neurologic workup in patients suspected to have ECDS or PHA. Current treatment recommendations include topical, intralesional, and oral corticosteroids; methotrexate; and surgical grafts. Although ECDS is a rare entity, more intensive research is needed on the exact pathophysiology and effective treatment options that focus on improving the cosmetic outcome in these patients. Cosmesis is the primary concern in patients with ECDS and should be managed early and appropriately to prevent long-term psychological sequelae.

1. Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:62-73.

2. Picket AJ, Carpentieri D, Price H, et al. Early morphea mimicking acquired port-wine stain. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:591-594.

3. Holland KE, Steffes B, Nocton JJ, et al. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre with associated neurologic abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2006;117:132-136.

4. Goh C, Biswas A, Goldberg LJ. Alopecia with perineural lymphocytes: a clue to linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:518-520.

5. Kreuter A. Localized scleroderma. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:135-147.

6. Tolkachjov SN, Patel NG, Tollefson MM. Progressive hemifacial atrophy: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:39.

7. Amaral TN, Marques Neto JF, Lapa AT, et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma en coup de sabre [published online January 27, 2012]. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:719685.

8. Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de sabre morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: a retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:257-263.

9. Zannin ME, Martini G, Athreya BH, et al. Ocular involvement in children with localized scleroderma: a multi-center study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1311-1314.

10. Polcari I, Moon A, Mathes EF, et al. Headaches as a presenting symptom of linear morphea en coup de sabre. Pediatrics. 2014;134:1715-1719.

11. Doolittle DA, Lehman VT, Schwartz KM, et al. CNS imaging findings associated with Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre: correlation to dermatologic and neurologic abnormalities. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:21-34.

12. Pierre-Louis M, Sperling LC, Wilke MS, et al. Distinctive histopathologic findings in linear morphea (en coup de sabre) alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:580-584.

13. Thareja SK, Sadhwani D, Alan Fenske N. En coup de sabre morphea treated with hyaluronic acid filler. Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:823-826.

14. Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

15. Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:385-396.

16. Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW, et al. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:545-550.

17. Kurzinski K, Torok KS. Cytokine profiles in localized scleroderma and relationship to clinical features. Cytokine. 2011;55:157-164.

18. Eisendle K, Grabner T, Zelger B. Morphoea: a manifestation of infection with Borrelia species? Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1189-1198.

19. Gutiérrez-Gómez C, Godínez-Hana AL, García-Hernández M, et al. Lack of IgG antibody seropositivity to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Parry-Romberg syndrome and linear morphea en coup de sabre in Mexico. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:947-951.

20. Miller K, Lehrhoff S, Fischer M, et al. Linear morphea of the forehead (en coup de sabre). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:22.

21. Hanson AH, Fivenson DP, Schapiro B. Linear scleroderma in an adolescent woman treated with methotrexate and excimer laser. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:203-205.

22. Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, et al. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1998-2006.

23. Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate in severe localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:847-852.

24. Weibel L, Sampaio MC, Visentin MT, et al. Evaluation of methotrexate and corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma (morphoea) in children. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1013-1020.

25. Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:286-294.

26. Nisticò SP, Saraceno R, Schipani C, et al. Different applications of monochromatic excimer light in skin diseases. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27:647-654.

27. Zwischenberger BA, Jacobe HT. A systematic review of morphea treatments and therapeutic algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:925-941.

28. Karaaltin MV, Akpinar AC, Baghaki S, et al. Treatment of “en coup de sabre” deformity with adipose-derived regenerative cell-enriched fat graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:103-105.

29. Consorti G, Tieghi R, Clauser LC. Frontal linear scleroderma: long-term result in volumetric restoration of the fronto-orbital area by structural fat grafting. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:263-265.

30. Cavusoglu T, Yazici I, Vargel I, et al. Reconstruction of coup de sabre deformity (linear localized scleroderma) by using galeal frontalis muscle flap and demineralized bone matrix combination. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:257-258.

31. Robitschek J, Wang D, Hall D. Treatment of linear scleroderma “en coup de sabre” with AlloDerm tissue matrix. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:540-541.

1. Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:62-73.

2. Picket AJ, Carpentieri D, Price H, et al. Early morphea mimicking acquired port-wine stain. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:591-594.

3. Holland KE, Steffes B, Nocton JJ, et al. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre with associated neurologic abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2006;117:132-136.

4. Goh C, Biswas A, Goldberg LJ. Alopecia with perineural lymphocytes: a clue to linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:518-520.

5. Kreuter A. Localized scleroderma. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:135-147.

6. Tolkachjov SN, Patel NG, Tollefson MM. Progressive hemifacial atrophy: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:39.

7. Amaral TN, Marques Neto JF, Lapa AT, et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma en coup de sabre [published online January 27, 2012]. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:719685.

8. Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de sabre morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: a retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:257-263.

9. Zannin ME, Martini G, Athreya BH, et al. Ocular involvement in children with localized scleroderma: a multi-center study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1311-1314.

10. Polcari I, Moon A, Mathes EF, et al. Headaches as a presenting symptom of linear morphea en coup de sabre. Pediatrics. 2014;134:1715-1719.

11. Doolittle DA, Lehman VT, Schwartz KM, et al. CNS imaging findings associated with Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre: correlation to dermatologic and neurologic abnormalities. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:21-34.

12. Pierre-Louis M, Sperling LC, Wilke MS, et al. Distinctive histopathologic findings in linear morphea (en coup de sabre) alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:580-584.

13. Thareja SK, Sadhwani D, Alan Fenske N. En coup de sabre morphea treated with hyaluronic acid filler. Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:823-826.

14. Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

15. Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:385-396.

16. Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW, et al. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:545-550.

17. Kurzinski K, Torok KS. Cytokine profiles in localized scleroderma and relationship to clinical features. Cytokine. 2011;55:157-164.

18. Eisendle K, Grabner T, Zelger B. Morphoea: a manifestation of infection with Borrelia species? Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1189-1198.

19. Gutiérrez-Gómez C, Godínez-Hana AL, García-Hernández M, et al. Lack of IgG antibody seropositivity to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Parry-Romberg syndrome and linear morphea en coup de sabre in Mexico. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:947-951.

20. Miller K, Lehrhoff S, Fischer M, et al. Linear morphea of the forehead (en coup de sabre). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:22.

21. Hanson AH, Fivenson DP, Schapiro B. Linear scleroderma in an adolescent woman treated with methotrexate and excimer laser. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:203-205.

22. Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, et al. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1998-2006.

23. Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate in severe localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:847-852.

24. Weibel L, Sampaio MC, Visentin MT, et al. Evaluation of methotrexate and corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma (morphoea) in children. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1013-1020.

25. Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:286-294.

26. Nisticò SP, Saraceno R, Schipani C, et al. Different applications of monochromatic excimer light in skin diseases. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27:647-654.

27. Zwischenberger BA, Jacobe HT. A systematic review of morphea treatments and therapeutic algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:925-941.

28. Karaaltin MV, Akpinar AC, Baghaki S, et al. Treatment of “en coup de sabre” deformity with adipose-derived regenerative cell-enriched fat graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:103-105.

29. Consorti G, Tieghi R, Clauser LC. Frontal linear scleroderma: long-term result in volumetric restoration of the fronto-orbital area by structural fat grafting. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:263-265.

30. Cavusoglu T, Yazici I, Vargel I, et al. Reconstruction of coup de sabre deformity (linear localized scleroderma) by using galeal frontalis muscle flap and demineralized bone matrix combination. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:257-258.

31. Robitschek J, Wang D, Hall D. Treatment of linear scleroderma “en coup de sabre” with AlloDerm tissue matrix. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:540-541.

Practice Points

• En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear

scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a

unilateral distribution.

• Neurologic involvement is common and should

prompt a comprehensive neurologic workup in

patients suspected to have ECDS or progressive

hemiface atrophy.

• Corticosteroids remain the treatment of choice, but

other modalities such as methotrexate, excimer laser,

and grafting have been used with varying success.

Panniculitis, Pancreatitis, and Polyarthritis: A Rare Clinical Syndrome

Pancreatic panniculitis is a rare disease contributing to widespread fat necrosis in patients with underlying pancreatic disorders. This entity was first described in 1883,1 but it was not until 1947 that it was reported in the English-language literature.2 Patients with pancreatitis infrequently develop extrapancreatic manifestations. It has been estimated that only 2% to 3% of patients worldwide with an underlying pancreatic disease develop cutaneous lesions.3 Patients who develop pancreatic panniculitis typically present with tender, edematous, erythematous to brown, subcutaneous nodules on the lower legs with the tendency for spontaneous ulceration. Lesions tend to exude a viscous, yellow-brown, oily substance that represents liquefactive necrosis of enzymatic fat in subcutaneous tissue. Cutaneous lesions may precede, occur simultaneously, or follow the development of an underlying pancreatic disorder. Rarely, patients may develop inflammatory arthritis secondary to intraosseous fat necrosis, completing the triad of findings diagnostic for panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Although the underlying pancreatic pathology may vary, roughly 80% of cases worldwide have acute/chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma, most commonly acinar cell carcinoma.4-6 Less common pancreatic disorders include pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreatic divisum, and vascular pancreatic fistulas.7 Narváez et al8 found that of the 25 cases of PPP syndrome reported in the literature, 68% (17/25) were men, 32% (8/25) were women, 56% (14/25) were younger than 50 years, and 64% (16/25) had a history of prior or current alcohol abuse.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man with a history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic pancreatitis of unknown etiology, and arthritis presented to our clinic for evaluation of painful skin nodules on the lower legs of 8 months’ duration, in addition to joint pain and swelling of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), metatarsophalangeal, and ankle joints. He had a history of numerous hospital admissions over the last 2 years for pancreatitis and was being managed by the rheumatology department for arthritic symptoms.

Physical examination revealed multiple 1- to 4-cm, ill-defined, erythematous to brown, subcutaneous nodules on the bilateral lower legs (Figure 1) and right inferomedial thigh that were tender to palpation. Marked erythema and edema of the MCP and metatarsophalangeal joints (Figure 2) and bilateral ankles were observed. Diffuse 2+ pitting edema was present in the bilateral lower extremities, along with areas of hyperpigmentation overlying resolving lesions.

Laboratory data revealed an elevated lipase level (>16,000 U/L [reference range, 31–186 U/L]), amylase level (>4700 U/L [reference range, 27–131 U/L]), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (94 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]), and C-reactive protein level (93.5 mg/L [0.08–3.1 mg/L]). The patient had more than 6 episodes of recurrent idiopathic pancreatitis over the last 2 years, though symptoms of abdominal pain were minimal to nonexistent. Liver function tests and alcohol, calcium, and triglyceride levels all were within reference range. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies were negative.

Ultrasonography showed no evidence of cholelithiasis. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a 1.8×1.4-cm hypodense lesion within the pancreatic head with calcifications and mild proximal pancreatic ductal dilatation (Figure 3). However, multiple magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography examinations and endoscopic ultrasounds with fine-needle aspiration specimens were performed, all negative for malignancy. Computed tomography of the left ankle demonstrated evidence of bony cortical destruction in the lateral aspect of the posterior calcaneus. Bone biopsy specimens demonstrated mild chronic inflammation with no evidence of osteomyelitis. A serum uric acid level was found to be 4.4 mg/dL (reference range, 4.0–8.0 mg/dL) and a joint aspirate demonstrated turbid fluid with lipoid material and no evidence of crystals or organisms on culture. Furthermore, a 4-mm punch biopsy of a nodule on the right leg revealed extensive lobular and septal liquefactive adipocyte necrosis with scattered neutrophils and lymphocytes (Figure 4). Aggregates of fine granular basophilic material were observed with prominent adipocyte degeneration and calcification.

Symptomatic treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) along with intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids had proven ineffective in the management of this patient. He was subsequently referred to the surgery department for a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) with notable improvement in pancreatic enzyme levels, lower leg subcutaneous nodules, and arthritis weeks after surgery.

Comment

A triad of pancreatic panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis characterizes a rare entity known as PPP syndrome. Pancreatic panniculitis is a rare form of subcutaneous lobular fat necrosis associated with various underlying pancreatic disorders. Approximately 0.3% to 3.0% of patients with an underlying pancreatic disorder are affected with pancreatic panniculitis.9 Pancreatic panniculitis has been found in roughly 2% to 3% of patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma, most commonly the acinar cell type.10 Narváez et al8 reported that nearly two-thirds of patients diagnosed with PPP syndrome have minimal to absent abdominal symptoms that often lead to misdiagnosis and affect the overall prognosis of patients with pancreatic disease. Any delay in the diagnosis of PPP syndrome leads to a worse prognosis, with a mortality rate reported to be approximately 24%.8 Potts et al5 provided a review of 27 patients with pancreatic panniculitis in which all 8 patients with pancreatic carcinoma and 42% (8/19) of patients with pancreatitis died.

Pancreatic panniculitis in the setting of PPP syndrome commonly presents with erythematous to brown, exquisitely tender, edematous, subcutaneous nodules on the lower legs. Lesions can range in size from several millimeters to 5 cm. The subcutaneous nodules may spontaneously ulcerate and exude oily viscous material from the liquefactive necrosis of adipocytes. In approximately 40% of patients, skin lesions are the presenting feature.11 Lesions typically resolve only after the pancreatic inflammation regresses, leaving behind atrophic hyperpigmented scars.3 Other presenting symptoms may include joint pain, pitting edema, and subcutaneous nodules, which can precede the diagnosis by up to 9 months.

The exact pathogenesis of PPP syndrome remains unclear. The most widely recognized hypothesis suggests that pancreatic enzymes (eg, trypsin, amylase, lipase, phospholipase A) released from the damaged pancreas are transported through the bloodstream to distant visceral and soft tissue sites, leading to lipolysis and inflammation to the surrounding subcutis and bone marrow.3 Ferrari et al12 reported this effect as a product of the accumulation of high levels of free fatty acids within the joint space by the action of lipolytic pancreatic enzymes on adipose cell membranes, resulting in acute arthritis.

Histopathologic findings of pancreatic panniculitis vary based on the acuity of the disease. Acute lesions typically demonstrate lobular and septal panniculitis. Szymanski and Bluefarb13 described the pathognomonic histologic findings of focal liquefactive necrosis and anucleate necrotic adipocytes surrounded by a shadowy and thickened cell membrane signifying the characteristic ghost cells. Fine basophilic material also may be seen intermixed with the necrotic adipocytes, representing saponified calcium. A brisk inflammatory infiltrate involving lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils tends to surround the areas of necrotic adipocytes. Chronic lesions often demonstrate a paucity of fat necrosis and ghost cells and more granulomatous infiltrate. Langerhans giant cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes predominate in the subcutaneous fat.

Laboratory findings associated with pancreatic panniculitis may include elevated serum amylase, lipase, and/or trypsin levels. Not all the enzymes have to be elevated simultaneously. On occasion, one enzyme may be within reference range while the others are elevated. Rarely, patients may have an elevated lipase level with no signs of underlying pancreatic disease, which demonstrates that panniculitis does not correlate with the enzyme levels. In all cases of suspected pancreatic panniculitis, a complete laboratory workup is recommended including lipase, amylase, and trypsin serum levels. Eosinophilia may be a prominent finding in patients with pancreatic panniculitis and tends to occur in association with an underlying pancreatic carcinoma. Patients with pancreatic panniculitis associated with pancreatic carcinoma tend to have more severe, diffuse, and persistent subcutaneous nodules that often are refractory to treatment with frequent recurrence. A rare constellation of findings known as Schmid triad is comprised of panniculitis, polyarthritis, and eosinophilia and typically portends a poor prognosis secondary to an underlying pancreatic tumor.14 Cutaneous nodules may predate the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma by several months, thus signifying the need for a high index of suspicion in patients with lower leg subcutaneous nodules.

Joint disease most commonly involves the ankles, knees, wrists, and MCP joints.5,6,11 It has been suggested that arthritic symptoms are from periarticular fat necrosis or a direct extension from the necrotic subcutaneous tissue to the adjacent joint space.15 Dahl et al3 reported the composition of joint effusion fluid in 3 patients with PPP syndrome. The aspirate in all 3 patients contained viscous yellow material similar to the necrotic adipose tissue seen draining from subcutaneous nodules. Joint aspirate analysis demonstrated increased concentration of free fatty acids in the joint fluid consistent with severe lipolysis.3

The PPP syndrome acronym may be misleading to physicians, as arthritis is not always polyarticular. Dahl et al3 reported that monoarticular or oligoarticular arthritic symptoms were present in 56% of patients studied. In rare cases, the arthritic symptoms antedated the diagnosis of clinically asymptomatic pancreatic disease. Arthritis can be either symmetric or asymmetric and infrequently follows a chronic course, leading to radiographic lytic lesions and symptoms that often are unresponsive to conventional therapy.16

Treatment of PPP syndrome is largely supportive, with a focus on correcting the underlying pancreatic disease. It is imperative to identify any complicating factors contributing to high levels of circulating pancreatic enzymes. Pseudocysts must be addressed if discovered in these patients, as they often perpetuate the substantial release of pancreatic enzymes into the serum, leading to characteristic subcutaneous fat necrosis and arthritis. Sepsis also is a concern, likely secondary to bacterial colonization of the ulcerated subcutaneous nodules and compromised skin barrier. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids have been used for symptomatic relief but usually are ineffective and have not been shown to reduce the duration of the disease.12,16 Octreotide has been utilized and may potentially reduce pancreatic enzyme secretion leading to improvement in cutaneous and musculoskeletal lesions.17 Plasmapheresis has been used as an adjuvant treatment in patients with persistent hyperamylasemia and hyperlipasemia, but reports are anecdotal. Often reserved for severe disease, cholecystectomy, pancreatic duct removal, and pancreaticoduodenectomy have demonstrated success in the management of chronic pancreatitis and panniculitis. Dahl et al3 reported 2 cases in which cholecystectomy was performed with complete resolution of the skin and pancreatic disease. Our patient was initially treated symptomatically with NSAIDs and corticosteroids but there was no clinical response. The patient eventually underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy 9 months after the onset of symptoms with complete resolution of joint pain and swelling, greater than 50% resolution of his lower leg subcutaneous nodules, and remarkable reduction in amylase and lipase levels on 1-month follow-up.

Conclusion

Panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare diagnosis characterized by a triad of pancreatic panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis. Adjuvant therapies for PPP syndrome, such as NSAIDs, corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, and octreotide, have been used with equivocal results, but definitive treatment requires correction of the primary pancreatic disorder. More importantly, many pancreatic diseases can cause pancreatic panniculitis, but extensive, refractory, or ulcerated cases could be an early indicator of an occult pancreatic malignancy and should prompt early evaluation with a multidisciplinary approach. This approach should incorporate management from dermatology, internal medicine, rheumatology, gastroenterology, surgery, and primary care.

- Chiari H. Uber die Sogenannte Fettnekrose. Prag Med Wochenschr. 1883;8:285-286, 299-301.

- Blauvelt H. Case of acute pancreatitis with subcutaneous fat necrosis. Br J Surg. 1946;34:207-208.

- Dahl PR, Su D, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

- Mullen GT, Caperton EM Jr, Crespin SR, et al. Arthritis and skin lesions resembling erythema nodosum in pancreatic disease. Ann Intern Med. 1968;68:75-87.

- Potts DE, Mass MF, Iseman MD. Syndrome and pancreatic disease, subcutaneous fat necrosis and polyserositis: case report and review of literature. Am J Med. 1975;58:417-423.

- Sorensen EV. Subcutaneous fat necrosis in pancreatic disease: a review and two new case reports. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:71-75.

- García-Romero D, Vanaclocha F. Pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:465-470.

- Narváez J, Bianchi M, Santo P, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:417-423.

- Rongioetti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

- Poelman SM, Nguyen K. Pancreatic panniculitis associated with acinar cell pancreatic carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:38-42.

- Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975:111:506-510.

- Ferrari R, Wendelboe M, Ford PM, et al. Pancreatitis arthritis with periarticular fat necrosis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1436-1437.

- Szymanski FJ, Bluefarb SM. Nodular fat necrosis and pancreatic diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:224-229.

- Beltraminelly HS, Buechner SA, Hausermann P. Pancreatic panniculitis in a patient with an acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Dermatology. 2004;208:265-267.

- Burns WA, Matthews MJ, Hamosh M, et al. Lipase-secreting acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas with polyarthropathy: a light and electron microscopic, histochemical, and biochemical study. Cancer. 1974;33:1002-1009.

- Baron M, Paltiel H, Lander P. Aseptic necrosis of the talus and calcaneal insufficiency fractures in a patient with pancreatitis, subcutaneous fat necrosis, and arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:1309-1313.

- Zundler S, Erber R, Agaimy A, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis in a patient with pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the liver—case report and review of literature. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:130.

Pancreatic panniculitis is a rare disease contributing to widespread fat necrosis in patients with underlying pancreatic disorders. This entity was first described in 1883,1 but it was not until 1947 that it was reported in the English-language literature.2 Patients with pancreatitis infrequently develop extrapancreatic manifestations. It has been estimated that only 2% to 3% of patients worldwide with an underlying pancreatic disease develop cutaneous lesions.3 Patients who develop pancreatic panniculitis typically present with tender, edematous, erythematous to brown, subcutaneous nodules on the lower legs with the tendency for spontaneous ulceration. Lesions tend to exude a viscous, yellow-brown, oily substance that represents liquefactive necrosis of enzymatic fat in subcutaneous tissue. Cutaneous lesions may precede, occur simultaneously, or follow the development of an underlying pancreatic disorder. Rarely, patients may develop inflammatory arthritis secondary to intraosseous fat necrosis, completing the triad of findings diagnostic for panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Although the underlying pancreatic pathology may vary, roughly 80% of cases worldwide have acute/chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma, most commonly acinar cell carcinoma.4-6 Less common pancreatic disorders include pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreatic divisum, and vascular pancreatic fistulas.7 Narváez et al8 found that of the 25 cases of PPP syndrome reported in the literature, 68% (17/25) were men, 32% (8/25) were women, 56% (14/25) were younger than 50 years, and 64% (16/25) had a history of prior or current alcohol abuse.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man with a history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic pancreatitis of unknown etiology, and arthritis presented to our clinic for evaluation of painful skin nodules on the lower legs of 8 months’ duration, in addition to joint pain and swelling of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), metatarsophalangeal, and ankle joints. He had a history of numerous hospital admissions over the last 2 years for pancreatitis and was being managed by the rheumatology department for arthritic symptoms.

Physical examination revealed multiple 1- to 4-cm, ill-defined, erythematous to brown, subcutaneous nodules on the bilateral lower legs (Figure 1) and right inferomedial thigh that were tender to palpation. Marked erythema and edema of the MCP and metatarsophalangeal joints (Figure 2) and bilateral ankles were observed. Diffuse 2+ pitting edema was present in the bilateral lower extremities, along with areas of hyperpigmentation overlying resolving lesions.

Laboratory data revealed an elevated lipase level (>16,000 U/L [reference range, 31–186 U/L]), amylase level (>4700 U/L [reference range, 27–131 U/L]), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (94 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]), and C-reactive protein level (93.5 mg/L [0.08–3.1 mg/L]). The patient had more than 6 episodes of recurrent idiopathic pancreatitis over the last 2 years, though symptoms of abdominal pain were minimal to nonexistent. Liver function tests and alcohol, calcium, and triglyceride levels all were within reference range. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies were negative.

Ultrasonography showed no evidence of cholelithiasis. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a 1.8×1.4-cm hypodense lesion within the pancreatic head with calcifications and mild proximal pancreatic ductal dilatation (Figure 3). However, multiple magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography examinations and endoscopic ultrasounds with fine-needle aspiration specimens were performed, all negative for malignancy. Computed tomography of the left ankle demonstrated evidence of bony cortical destruction in the lateral aspect of the posterior calcaneus. Bone biopsy specimens demonstrated mild chronic inflammation with no evidence of osteomyelitis. A serum uric acid level was found to be 4.4 mg/dL (reference range, 4.0–8.0 mg/dL) and a joint aspirate demonstrated turbid fluid with lipoid material and no evidence of crystals or organisms on culture. Furthermore, a 4-mm punch biopsy of a nodule on the right leg revealed extensive lobular and septal liquefactive adipocyte necrosis with scattered neutrophils and lymphocytes (Figure 4). Aggregates of fine granular basophilic material were observed with prominent adipocyte degeneration and calcification.

Symptomatic treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) along with intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids had proven ineffective in the management of this patient. He was subsequently referred to the surgery department for a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) with notable improvement in pancreatic enzyme levels, lower leg subcutaneous nodules, and arthritis weeks after surgery.

Comment

A triad of pancreatic panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis characterizes a rare entity known as PPP syndrome. Pancreatic panniculitis is a rare form of subcutaneous lobular fat necrosis associated with various underlying pancreatic disorders. Approximately 0.3% to 3.0% of patients with an underlying pancreatic disorder are affected with pancreatic panniculitis.9 Pancreatic panniculitis has been found in roughly 2% to 3% of patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma, most commonly the acinar cell type.10 Narváez et al8 reported that nearly two-thirds of patients diagnosed with PPP syndrome have minimal to absent abdominal symptoms that often lead to misdiagnosis and affect the overall prognosis of patients with pancreatic disease. Any delay in the diagnosis of PPP syndrome leads to a worse prognosis, with a mortality rate reported to be approximately 24%.8 Potts et al5 provided a review of 27 patients with pancreatic panniculitis in which all 8 patients with pancreatic carcinoma and 42% (8/19) of patients with pancreatitis died.

Pancreatic panniculitis in the setting of PPP syndrome commonly presents with erythematous to brown, exquisitely tender, edematous, subcutaneous nodules on the lower legs. Lesions can range in size from several millimeters to 5 cm. The subcutaneous nodules may spontaneously ulcerate and exude oily viscous material from the liquefactive necrosis of adipocytes. In approximately 40% of patients, skin lesions are the presenting feature.11 Lesions typically resolve only after the pancreatic inflammation regresses, leaving behind atrophic hyperpigmented scars.3 Other presenting symptoms may include joint pain, pitting edema, and subcutaneous nodules, which can precede the diagnosis by up to 9 months.

The exact pathogenesis of PPP syndrome remains unclear. The most widely recognized hypothesis suggests that pancreatic enzymes (eg, trypsin, amylase, lipase, phospholipase A) released from the damaged pancreas are transported through the bloodstream to distant visceral and soft tissue sites, leading to lipolysis and inflammation to the surrounding subcutis and bone marrow.3 Ferrari et al12 reported this effect as a product of the accumulation of high levels of free fatty acids within the joint space by the action of lipolytic pancreatic enzymes on adipose cell membranes, resulting in acute arthritis.

Histopathologic findings of pancreatic panniculitis vary based on the acuity of the disease. Acute lesions typically demonstrate lobular and septal panniculitis. Szymanski and Bluefarb13 described the pathognomonic histologic findings of focal liquefactive necrosis and anucleate necrotic adipocytes surrounded by a shadowy and thickened cell membrane signifying the characteristic ghost cells. Fine basophilic material also may be seen intermixed with the necrotic adipocytes, representing saponified calcium. A brisk inflammatory infiltrate involving lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils tends to surround the areas of necrotic adipocytes. Chronic lesions often demonstrate a paucity of fat necrosis and ghost cells and more granulomatous infiltrate. Langerhans giant cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes predominate in the subcutaneous fat.

Laboratory findings associated with pancreatic panniculitis may include elevated serum amylase, lipase, and/or trypsin levels. Not all the enzymes have to be elevated simultaneously. On occasion, one enzyme may be within reference range while the others are elevated. Rarely, patients may have an elevated lipase level with no signs of underlying pancreatic disease, which demonstrates that panniculitis does not correlate with the enzyme levels. In all cases of suspected pancreatic panniculitis, a complete laboratory workup is recommended including lipase, amylase, and trypsin serum levels. Eosinophilia may be a prominent finding in patients with pancreatic panniculitis and tends to occur in association with an underlying pancreatic carcinoma. Patients with pancreatic panniculitis associated with pancreatic carcinoma tend to have more severe, diffuse, and persistent subcutaneous nodules that often are refractory to treatment with frequent recurrence. A rare constellation of findings known as Schmid triad is comprised of panniculitis, polyarthritis, and eosinophilia and typically portends a poor prognosis secondary to an underlying pancreatic tumor.14 Cutaneous nodules may predate the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma by several months, thus signifying the need for a high index of suspicion in patients with lower leg subcutaneous nodules.

Joint disease most commonly involves the ankles, knees, wrists, and MCP joints.5,6,11 It has been suggested that arthritic symptoms are from periarticular fat necrosis or a direct extension from the necrotic subcutaneous tissue to the adjacent joint space.15 Dahl et al3 reported the composition of joint effusion fluid in 3 patients with PPP syndrome. The aspirate in all 3 patients contained viscous yellow material similar to the necrotic adipose tissue seen draining from subcutaneous nodules. Joint aspirate analysis demonstrated increased concentration of free fatty acids in the joint fluid consistent with severe lipolysis.3

The PPP syndrome acronym may be misleading to physicians, as arthritis is not always polyarticular. Dahl et al3 reported that monoarticular or oligoarticular arthritic symptoms were present in 56% of patients studied. In rare cases, the arthritic symptoms antedated the diagnosis of clinically asymptomatic pancreatic disease. Arthritis can be either symmetric or asymmetric and infrequently follows a chronic course, leading to radiographic lytic lesions and symptoms that often are unresponsive to conventional therapy.16

Treatment of PPP syndrome is largely supportive, with a focus on correcting the underlying pancreatic disease. It is imperative to identify any complicating factors contributing to high levels of circulating pancreatic enzymes. Pseudocysts must be addressed if discovered in these patients, as they often perpetuate the substantial release of pancreatic enzymes into the serum, leading to characteristic subcutaneous fat necrosis and arthritis. Sepsis also is a concern, likely secondary to bacterial colonization of the ulcerated subcutaneous nodules and compromised skin barrier. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids have been used for symptomatic relief but usually are ineffective and have not been shown to reduce the duration of the disease.12,16 Octreotide has been utilized and may potentially reduce pancreatic enzyme secretion leading to improvement in cutaneous and musculoskeletal lesions.17 Plasmapheresis has been used as an adjuvant treatment in patients with persistent hyperamylasemia and hyperlipasemia, but reports are anecdotal. Often reserved for severe disease, cholecystectomy, pancreatic duct removal, and pancreaticoduodenectomy have demonstrated success in the management of chronic pancreatitis and panniculitis. Dahl et al3 reported 2 cases in which cholecystectomy was performed with complete resolution of the skin and pancreatic disease. Our patient was initially treated symptomatically with NSAIDs and corticosteroids but there was no clinical response. The patient eventually underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy 9 months after the onset of symptoms with complete resolution of joint pain and swelling, greater than 50% resolution of his lower leg subcutaneous nodules, and remarkable reduction in amylase and lipase levels on 1-month follow-up.

Conclusion

Panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare diagnosis characterized by a triad of pancreatic panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis. Adjuvant therapies for PPP syndrome, such as NSAIDs, corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, and octreotide, have been used with equivocal results, but definitive treatment requires correction of the primary pancreatic disorder. More importantly, many pancreatic diseases can cause pancreatic panniculitis, but extensive, refractory, or ulcerated cases could be an early indicator of an occult pancreatic malignancy and should prompt early evaluation with a multidisciplinary approach. This approach should incorporate management from dermatology, internal medicine, rheumatology, gastroenterology, surgery, and primary care.

Pancreatic panniculitis is a rare disease contributing to widespread fat necrosis in patients with underlying pancreatic disorders. This entity was first described in 1883,1 but it was not until 1947 that it was reported in the English-language literature.2 Patients with pancreatitis infrequently develop extrapancreatic manifestations. It has been estimated that only 2% to 3% of patients worldwide with an underlying pancreatic disease develop cutaneous lesions.3 Patients who develop pancreatic panniculitis typically present with tender, edematous, erythematous to brown, subcutaneous nodules on the lower legs with the tendency for spontaneous ulceration. Lesions tend to exude a viscous, yellow-brown, oily substance that represents liquefactive necrosis of enzymatic fat in subcutaneous tissue. Cutaneous lesions may precede, occur simultaneously, or follow the development of an underlying pancreatic disorder. Rarely, patients may develop inflammatory arthritis secondary to intraosseous fat necrosis, completing the triad of findings diagnostic for panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Although the underlying pancreatic pathology may vary, roughly 80% of cases worldwide have acute/chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma, most commonly acinar cell carcinoma.4-6 Less common pancreatic disorders include pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreatic divisum, and vascular pancreatic fistulas.7 Narváez et al8 found that of the 25 cases of PPP syndrome reported in the literature, 68% (17/25) were men, 32% (8/25) were women, 56% (14/25) were younger than 50 years, and 64% (16/25) had a history of prior or current alcohol abuse.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man with a history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic pancreatitis of unknown etiology, and arthritis presented to our clinic for evaluation of painful skin nodules on the lower legs of 8 months’ duration, in addition to joint pain and swelling of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), metatarsophalangeal, and ankle joints. He had a history of numerous hospital admissions over the last 2 years for pancreatitis and was being managed by the rheumatology department for arthritic symptoms.

Physical examination revealed multiple 1- to 4-cm, ill-defined, erythematous to brown, subcutaneous nodules on the bilateral lower legs (Figure 1) and right inferomedial thigh that were tender to palpation. Marked erythema and edema of the MCP and metatarsophalangeal joints (Figure 2) and bilateral ankles were observed. Diffuse 2+ pitting edema was present in the bilateral lower extremities, along with areas of hyperpigmentation overlying resolving lesions.

Laboratory data revealed an elevated lipase level (>16,000 U/L [reference range, 31–186 U/L]), amylase level (>4700 U/L [reference range, 27–131 U/L]), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (94 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]), and C-reactive protein level (93.5 mg/L [0.08–3.1 mg/L]). The patient had more than 6 episodes of recurrent idiopathic pancreatitis over the last 2 years, though symptoms of abdominal pain were minimal to nonexistent. Liver function tests and alcohol, calcium, and triglyceride levels all were within reference range. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies were negative.

Ultrasonography showed no evidence of cholelithiasis. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a 1.8×1.4-cm hypodense lesion within the pancreatic head with calcifications and mild proximal pancreatic ductal dilatation (Figure 3). However, multiple magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography examinations and endoscopic ultrasounds with fine-needle aspiration specimens were performed, all negative for malignancy. Computed tomography of the left ankle demonstrated evidence of bony cortical destruction in the lateral aspect of the posterior calcaneus. Bone biopsy specimens demonstrated mild chronic inflammation with no evidence of osteomyelitis. A serum uric acid level was found to be 4.4 mg/dL (reference range, 4.0–8.0 mg/dL) and a joint aspirate demonstrated turbid fluid with lipoid material and no evidence of crystals or organisms on culture. Furthermore, a 4-mm punch biopsy of a nodule on the right leg revealed extensive lobular and septal liquefactive adipocyte necrosis with scattered neutrophils and lymphocytes (Figure 4). Aggregates of fine granular basophilic material were observed with prominent adipocyte degeneration and calcification.

Symptomatic treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) along with intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids had proven ineffective in the management of this patient. He was subsequently referred to the surgery department for a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) with notable improvement in pancreatic enzyme levels, lower leg subcutaneous nodules, and arthritis weeks after surgery.

Comment

A triad of pancreatic panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis characterizes a rare entity known as PPP syndrome. Pancreatic panniculitis is a rare form of subcutaneous lobular fat necrosis associated with various underlying pancreatic disorders. Approximately 0.3% to 3.0% of patients with an underlying pancreatic disorder are affected with pancreatic panniculitis.9 Pancreatic panniculitis has been found in roughly 2% to 3% of patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma, most commonly the acinar cell type.10 Narváez et al8 reported that nearly two-thirds of patients diagnosed with PPP syndrome have minimal to absent abdominal symptoms that often lead to misdiagnosis and affect the overall prognosis of patients with pancreatic disease. Any delay in the diagnosis of PPP syndrome leads to a worse prognosis, with a mortality rate reported to be approximately 24%.8 Potts et al5 provided a review of 27 patients with pancreatic panniculitis in which all 8 patients with pancreatic carcinoma and 42% (8/19) of patients with pancreatitis died.

Pancreatic panniculitis in the setting of PPP syndrome commonly presents with erythematous to brown, exquisitely tender, edematous, subcutaneous nodules on the lower legs. Lesions can range in size from several millimeters to 5 cm. The subcutaneous nodules may spontaneously ulcerate and exude oily viscous material from the liquefactive necrosis of adipocytes. In approximately 40% of patients, skin lesions are the presenting feature.11 Lesions typically resolve only after the pancreatic inflammation regresses, leaving behind atrophic hyperpigmented scars.3 Other presenting symptoms may include joint pain, pitting edema, and subcutaneous nodules, which can precede the diagnosis by up to 9 months.

The exact pathogenesis of PPP syndrome remains unclear. The most widely recognized hypothesis suggests that pancreatic enzymes (eg, trypsin, amylase, lipase, phospholipase A) released from the damaged pancreas are transported through the bloodstream to distant visceral and soft tissue sites, leading to lipolysis and inflammation to the surrounding subcutis and bone marrow.3 Ferrari et al12 reported this effect as a product of the accumulation of high levels of free fatty acids within the joint space by the action of lipolytic pancreatic enzymes on adipose cell membranes, resulting in acute arthritis.

Histopathologic findings of pancreatic panniculitis vary based on the acuity of the disease. Acute lesions typically demonstrate lobular and septal panniculitis. Szymanski and Bluefarb13 described the pathognomonic histologic findings of focal liquefactive necrosis and anucleate necrotic adipocytes surrounded by a shadowy and thickened cell membrane signifying the characteristic ghost cells. Fine basophilic material also may be seen intermixed with the necrotic adipocytes, representing saponified calcium. A brisk inflammatory infiltrate involving lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils tends to surround the areas of necrotic adipocytes. Chronic lesions often demonstrate a paucity of fat necrosis and ghost cells and more granulomatous infiltrate. Langerhans giant cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes predominate in the subcutaneous fat.

Laboratory findings associated with pancreatic panniculitis may include elevated serum amylase, lipase, and/or trypsin levels. Not all the enzymes have to be elevated simultaneously. On occasion, one enzyme may be within reference range while the others are elevated. Rarely, patients may have an elevated lipase level with no signs of underlying pancreatic disease, which demonstrates that panniculitis does not correlate with the enzyme levels. In all cases of suspected pancreatic panniculitis, a complete laboratory workup is recommended including lipase, amylase, and trypsin serum levels. Eosinophilia may be a prominent finding in patients with pancreatic panniculitis and tends to occur in association with an underlying pancreatic carcinoma. Patients with pancreatic panniculitis associated with pancreatic carcinoma tend to have more severe, diffuse, and persistent subcutaneous nodules that often are refractory to treatment with frequent recurrence. A rare constellation of findings known as Schmid triad is comprised of panniculitis, polyarthritis, and eosinophilia and typically portends a poor prognosis secondary to an underlying pancreatic tumor.14 Cutaneous nodules may predate the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma by several months, thus signifying the need for a high index of suspicion in patients with lower leg subcutaneous nodules.

Joint disease most commonly involves the ankles, knees, wrists, and MCP joints.5,6,11 It has been suggested that arthritic symptoms are from periarticular fat necrosis or a direct extension from the necrotic subcutaneous tissue to the adjacent joint space.15 Dahl et al3 reported the composition of joint effusion fluid in 3 patients with PPP syndrome. The aspirate in all 3 patients contained viscous yellow material similar to the necrotic adipose tissue seen draining from subcutaneous nodules. Joint aspirate analysis demonstrated increased concentration of free fatty acids in the joint fluid consistent with severe lipolysis.3

The PPP syndrome acronym may be misleading to physicians, as arthritis is not always polyarticular. Dahl et al3 reported that monoarticular or oligoarticular arthritic symptoms were present in 56% of patients studied. In rare cases, the arthritic symptoms antedated the diagnosis of clinically asymptomatic pancreatic disease. Arthritis can be either symmetric or asymmetric and infrequently follows a chronic course, leading to radiographic lytic lesions and symptoms that often are unresponsive to conventional therapy.16

Treatment of PPP syndrome is largely supportive, with a focus on correcting the underlying pancreatic disease. It is imperative to identify any complicating factors contributing to high levels of circulating pancreatic enzymes. Pseudocysts must be addressed if discovered in these patients, as they often perpetuate the substantial release of pancreatic enzymes into the serum, leading to characteristic subcutaneous fat necrosis and arthritis. Sepsis also is a concern, likely secondary to bacterial colonization of the ulcerated subcutaneous nodules and compromised skin barrier. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids have been used for symptomatic relief but usually are ineffective and have not been shown to reduce the duration of the disease.12,16 Octreotide has been utilized and may potentially reduce pancreatic enzyme secretion leading to improvement in cutaneous and musculoskeletal lesions.17 Plasmapheresis has been used as an adjuvant treatment in patients with persistent hyperamylasemia and hyperlipasemia, but reports are anecdotal. Often reserved for severe disease, cholecystectomy, pancreatic duct removal, and pancreaticoduodenectomy have demonstrated success in the management of chronic pancreatitis and panniculitis. Dahl et al3 reported 2 cases in which cholecystectomy was performed with complete resolution of the skin and pancreatic disease. Our patient was initially treated symptomatically with NSAIDs and corticosteroids but there was no clinical response. The patient eventually underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy 9 months after the onset of symptoms with complete resolution of joint pain and swelling, greater than 50% resolution of his lower leg subcutaneous nodules, and remarkable reduction in amylase and lipase levels on 1-month follow-up.

Conclusion

Panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare diagnosis characterized by a triad of pancreatic panniculitis, pancreatitis, and polyarthritis. Adjuvant therapies for PPP syndrome, such as NSAIDs, corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, and octreotide, have been used with equivocal results, but definitive treatment requires correction of the primary pancreatic disorder. More importantly, many pancreatic diseases can cause pancreatic panniculitis, but extensive, refractory, or ulcerated cases could be an early indicator of an occult pancreatic malignancy and should prompt early evaluation with a multidisciplinary approach. This approach should incorporate management from dermatology, internal medicine, rheumatology, gastroenterology, surgery, and primary care.

- Chiari H. Uber die Sogenannte Fettnekrose. Prag Med Wochenschr. 1883;8:285-286, 299-301.

- Blauvelt H. Case of acute pancreatitis with subcutaneous fat necrosis. Br J Surg. 1946;34:207-208.

- Dahl PR, Su D, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

- Mullen GT, Caperton EM Jr, Crespin SR, et al. Arthritis and skin lesions resembling erythema nodosum in pancreatic disease. Ann Intern Med. 1968;68:75-87.