User login

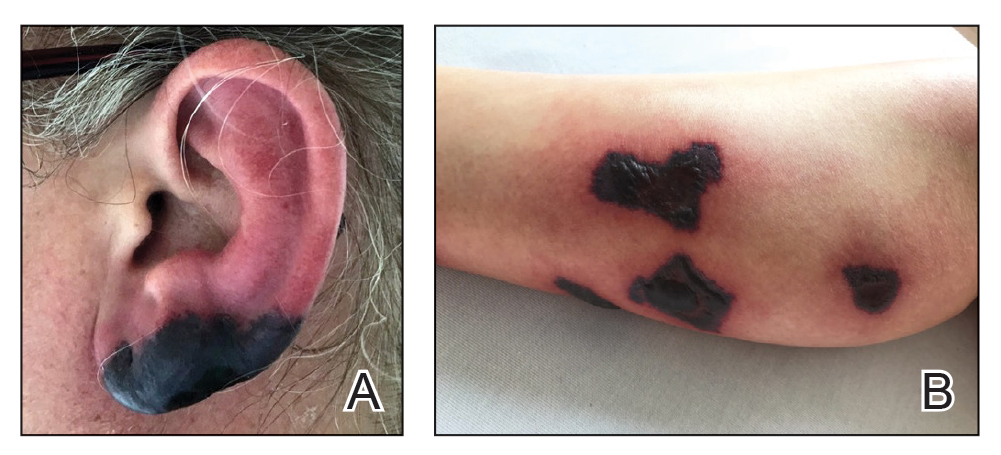

Bullous Retiform Purpura on the Ears and Legs

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

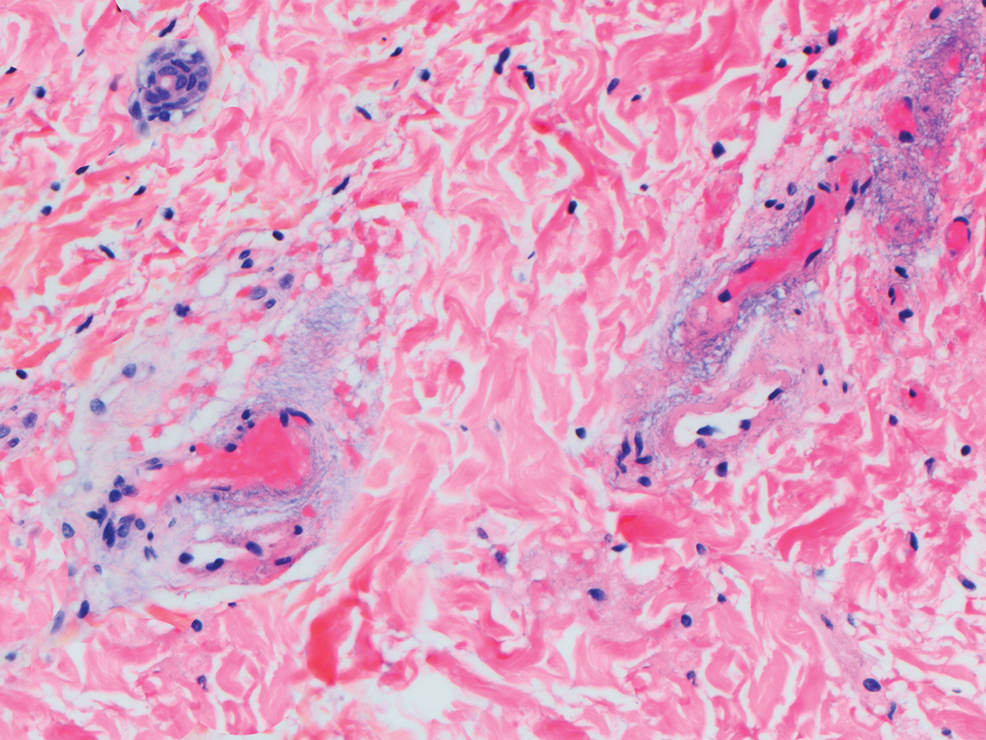

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

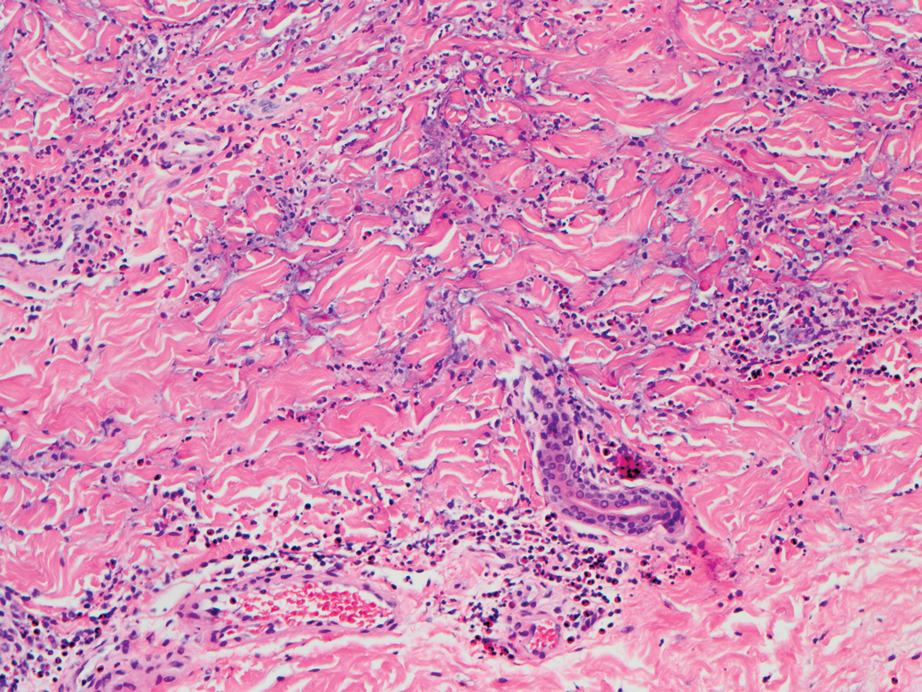

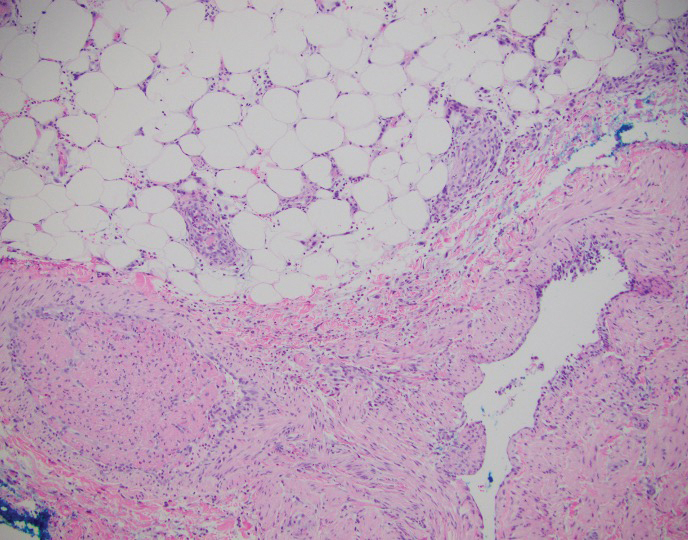

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

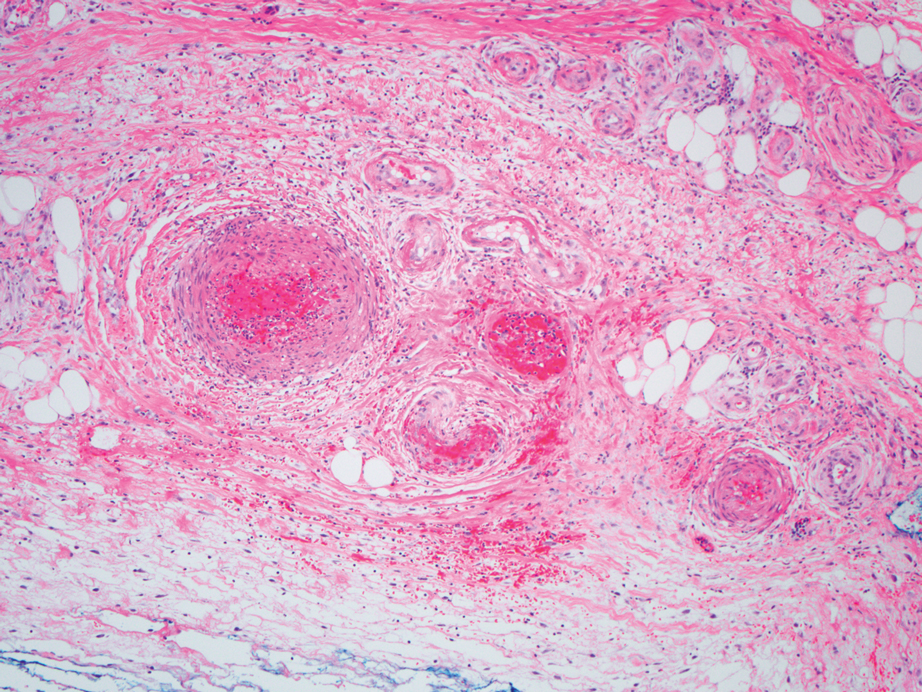

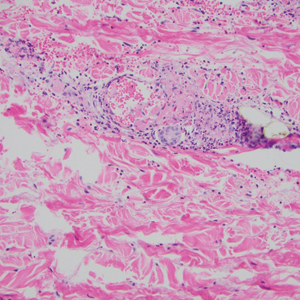

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

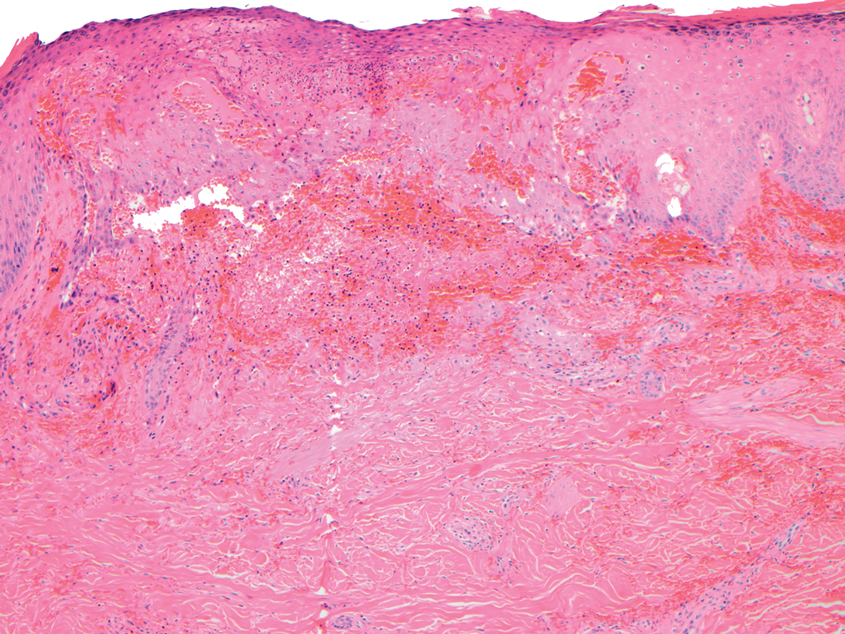

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

A 40-year-old woman presented with a progressive painful rash on the ears and legs of 2 weeks’ duration. She described the rash as initially red and nonpainful; it started on the right leg and progressed to the left leg, eventually involving the earlobes 4 days prior to presentation. Physical examination revealed edematous purpura of the earlobes and bullous retiform purpura on the lower extremities. Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia (3.6×103 /cm2 [reference range, 4.0–10.5×103 /cm2 ]) and elevated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (1:320 titer [reference range, <1:40]) in a perinuclear pattern (perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies). Urine toxicology screening was positive for cocaine and opiates. A punch biopsy of a bullous retiform purpura on the right thigh was obtained for standard hematoxylin and eosin staining.

En Coup de Sabre

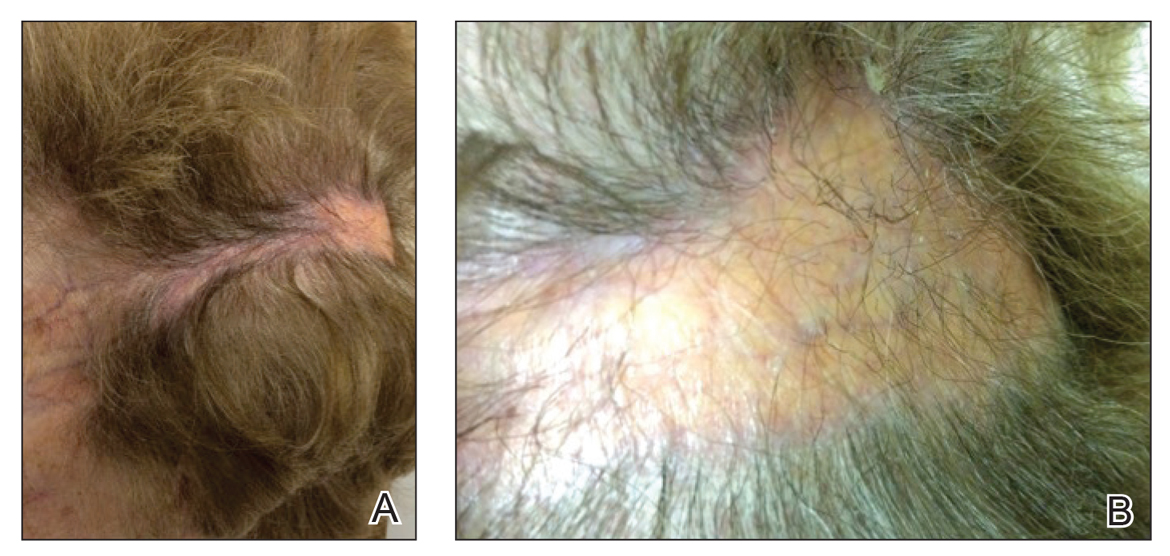

En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a unilateral distribution. The lesional skin first exhibits contraction and stiffness that lead to characteristic fibrotic plaques with associated linear alopecia.1 The pansclerotic plaques are ivory in color with hyperpigmented to violaceous borders extending as a paramedian band on the frontoparietal scalp.2,3 The skin lesions bear resemblance to the stroke of the sabre sword, giving the condition its unique name. Many patients initially present with concerns of frontal scalp alopecia.3 Linear morphea, including the ECDS subtype, is predominantly seen in children and women, usually presenting within the first 2 decades of life.1,4

The differential diagnoses of ECDS include focal dermal hypoplasia, steroid atrophy, localized morphea, and lupus profundus.5 En coup de sabre should be distinguished from progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA)(also known as Parry-Romberg syndrome).6 Progressive hemifacial atrophy presents as unilateral atrophy of the face involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and underlying bone in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.1 Both PHA and ECDS exist on a spectrum of linear scleroderma and may coexist in the same patient.6

There is a strong association with extracutaneous neurologic involvement, including seizures, ocular abnormalities, trigeminal neuralgia, and headache.7-10 One study examining ECDS and PHA demonstrated that 44% (19/43) of patients who underwent central nervous system imaging had abnormal findings.11 The majority of patients had magnetic resonance imaging with or without contrast, computed tomography, or both. The most common findings on T2-weighted images were white matter hyperintensities, mostly in subcortical and periventricular regions. The findings were bilateral in 61% (11/18) of patients and ipsilateral to the lesion in 33% (6/18) of patients.11 We present a case of ECDS masquerading as alopecia in a 77-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 77-year-old white woman presented with a chief concern of hair loss on the scalp that had been present since 12 years of age. During her adult life, the scalp lesion remained unchanged with no associated symptoms. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The patient denied any history of seizure disorders, facial paralysis, or neurologic deficits.

Comment

Etiology and Presentation

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear morphea that involves the frontoparietal scalp and forehead.7,12,13 It manifests as a solitary, linear, fibrous plaque that involves the skin, underlying muscle, and bone.7 Although most cases present with a single lesion, multiple lesions can occur.8 The exact etiology of this disease remains to be determined but is characterized by thickening and hardening of the skin secondary to increased collagen production.7 The incidence of linear morphea ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals and is more prevalent in white patients and women.14 Linear morphea is commonly found in children. Children are more likely to have linear morphea on the face, which can lead to lifelong disfigurement.2 Although the disease peaks in the fourth decade of life for adults, most pediatric cases are diagnosed between 2 and 14 years of age.14-16

Pathogenesis

Clinical and histopathological data suggest that a complex interaction among the vasculature, extracellular matrix, and immune system plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Similar to scleroderma, the CD4 helper T cell may be involved in the fibrotic changes that occur within these lesions.17 Early in the disease process, TH1 and TH17 inflammatory pathways predominate. The late fibrotic changes seen in scleroderma are more associated with a shift to the TH2 inflammatory pathway.17 Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi has been implicated abroad, but a large-scale study confirming Borrelia as a pathologic factor within morphea lesions has not been completed to date.18-20 Some authors believe early lesions of ECDS mimic erythema chronica migrans, with the late lesions resembling acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.20

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings of morphea tend to vary depending on the stage of the disease. The 2 stages of morphea can be differentiated by the degree of inflammation present histologically.14,21 The early phase of morphea primarily affects the connective and subcutaneous tissue surrounding eccrine sweat glands.14,21 A dense dermal and subcutaneous perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes is commonly observed.5 Later stages of the disease demonstrate densely packed homogenous collagen with minimal inflammation and loss of eccrine glands and blood vessels.14,21 The adipose tissue is generally replaced by sclerotic collagen, giving the biopsy a squared-off appearance.5,14

Management

En coup de sabre presents a treatment challenge. In active lesions, topical or intralesional corticosteroids are considered treatment of choice.5 Methotrexate has proven useful in the treatment of acute and deep forms of linear morphea. A study examining methotrexate in juvenile localized scleroderma, with the majority of patients having the linear subtype, revealed that methotrexate is both efficacious and well tolerated.22 Other reports in the literature reveal efficacy with the use of intravenous corticosteroids and methotrexate combination therapy for treatment of morphea.23,24 A longitudinal prospective study examining the use of high-dose methotrexate and oral corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma yielded positive results, with patients showing clinical improvement within 2 months of initiation of combination therapy.25 Other treatments include excimer laser; calcipotriene and tacrolimus; and surgical approaches such as autologous fat grafting, grafting with muscle flaps, and tissue inserts.21,26-31 In addition, patients can choose to forego therapy, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the ipsilateral scalp and face predominately in children and women. Neurologic involvement is common and should prompt a comprehensive neurologic workup in patients suspected to have ECDS or PHA. Current treatment recommendations include topical, intralesional, and oral corticosteroids; methotrexate; and surgical grafts. Although ECDS is a rare entity, more intensive research is needed on the exact pathophysiology and effective treatment options that focus on improving the cosmetic outcome in these patients. Cosmesis is the primary concern in patients with ECDS and should be managed early and appropriately to prevent long-term psychological sequelae.

1. Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:62-73.

2. Picket AJ, Carpentieri D, Price H, et al. Early morphea mimicking acquired port-wine stain. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:591-594.

3. Holland KE, Steffes B, Nocton JJ, et al. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre with associated neurologic abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2006;117:132-136.

4. Goh C, Biswas A, Goldberg LJ. Alopecia with perineural lymphocytes: a clue to linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:518-520.

5. Kreuter A. Localized scleroderma. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:135-147.

6. Tolkachjov SN, Patel NG, Tollefson MM. Progressive hemifacial atrophy: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:39.

7. Amaral TN, Marques Neto JF, Lapa AT, et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma en coup de sabre [published online January 27, 2012]. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:719685.

8. Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de sabre morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: a retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:257-263.

9. Zannin ME, Martini G, Athreya BH, et al. Ocular involvement in children with localized scleroderma: a multi-center study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1311-1314.

10. Polcari I, Moon A, Mathes EF, et al. Headaches as a presenting symptom of linear morphea en coup de sabre. Pediatrics. 2014;134:1715-1719.

11. Doolittle DA, Lehman VT, Schwartz KM, et al. CNS imaging findings associated with Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre: correlation to dermatologic and neurologic abnormalities. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:21-34.

12. Pierre-Louis M, Sperling LC, Wilke MS, et al. Distinctive histopathologic findings in linear morphea (en coup de sabre) alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:580-584.

13. Thareja SK, Sadhwani D, Alan Fenske N. En coup de sabre morphea treated with hyaluronic acid filler. Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:823-826.

14. Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

15. Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:385-396.

16. Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW, et al. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:545-550.

17. Kurzinski K, Torok KS. Cytokine profiles in localized scleroderma and relationship to clinical features. Cytokine. 2011;55:157-164.

18. Eisendle K, Grabner T, Zelger B. Morphoea: a manifestation of infection with Borrelia species? Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1189-1198.

19. Gutiérrez-Gómez C, Godínez-Hana AL, García-Hernández M, et al. Lack of IgG antibody seropositivity to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Parry-Romberg syndrome and linear morphea en coup de sabre in Mexico. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:947-951.

20. Miller K, Lehrhoff S, Fischer M, et al. Linear morphea of the forehead (en coup de sabre). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:22.

21. Hanson AH, Fivenson DP, Schapiro B. Linear scleroderma in an adolescent woman treated with methotrexate and excimer laser. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:203-205.

22. Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, et al. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1998-2006.

23. Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate in severe localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:847-852.

24. Weibel L, Sampaio MC, Visentin MT, et al. Evaluation of methotrexate and corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma (morphoea) in children. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1013-1020.

25. Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:286-294.

26. Nisticò SP, Saraceno R, Schipani C, et al. Different applications of monochromatic excimer light in skin diseases. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27:647-654.

27. Zwischenberger BA, Jacobe HT. A systematic review of morphea treatments and therapeutic algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:925-941.

28. Karaaltin MV, Akpinar AC, Baghaki S, et al. Treatment of “en coup de sabre” deformity with adipose-derived regenerative cell-enriched fat graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:103-105.

29. Consorti G, Tieghi R, Clauser LC. Frontal linear scleroderma: long-term result in volumetric restoration of the fronto-orbital area by structural fat grafting. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:263-265.

30. Cavusoglu T, Yazici I, Vargel I, et al. Reconstruction of coup de sabre deformity (linear localized scleroderma) by using galeal frontalis muscle flap and demineralized bone matrix combination. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:257-258.

31. Robitschek J, Wang D, Hall D. Treatment of linear scleroderma “en coup de sabre” with AlloDerm tissue matrix. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:540-541.

En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a unilateral distribution. The lesional skin first exhibits contraction and stiffness that lead to characteristic fibrotic plaques with associated linear alopecia.1 The pansclerotic plaques are ivory in color with hyperpigmented to violaceous borders extending as a paramedian band on the frontoparietal scalp.2,3 The skin lesions bear resemblance to the stroke of the sabre sword, giving the condition its unique name. Many patients initially present with concerns of frontal scalp alopecia.3 Linear morphea, including the ECDS subtype, is predominantly seen in children and women, usually presenting within the first 2 decades of life.1,4

The differential diagnoses of ECDS include focal dermal hypoplasia, steroid atrophy, localized morphea, and lupus profundus.5 En coup de sabre should be distinguished from progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA)(also known as Parry-Romberg syndrome).6 Progressive hemifacial atrophy presents as unilateral atrophy of the face involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and underlying bone in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.1 Both PHA and ECDS exist on a spectrum of linear scleroderma and may coexist in the same patient.6

There is a strong association with extracutaneous neurologic involvement, including seizures, ocular abnormalities, trigeminal neuralgia, and headache.7-10 One study examining ECDS and PHA demonstrated that 44% (19/43) of patients who underwent central nervous system imaging had abnormal findings.11 The majority of patients had magnetic resonance imaging with or without contrast, computed tomography, or both. The most common findings on T2-weighted images were white matter hyperintensities, mostly in subcortical and periventricular regions. The findings were bilateral in 61% (11/18) of patients and ipsilateral to the lesion in 33% (6/18) of patients.11 We present a case of ECDS masquerading as alopecia in a 77-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 77-year-old white woman presented with a chief concern of hair loss on the scalp that had been present since 12 years of age. During her adult life, the scalp lesion remained unchanged with no associated symptoms. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The patient denied any history of seizure disorders, facial paralysis, or neurologic deficits.

Comment

Etiology and Presentation

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear morphea that involves the frontoparietal scalp and forehead.7,12,13 It manifests as a solitary, linear, fibrous plaque that involves the skin, underlying muscle, and bone.7 Although most cases present with a single lesion, multiple lesions can occur.8 The exact etiology of this disease remains to be determined but is characterized by thickening and hardening of the skin secondary to increased collagen production.7 The incidence of linear morphea ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals and is more prevalent in white patients and women.14 Linear morphea is commonly found in children. Children are more likely to have linear morphea on the face, which can lead to lifelong disfigurement.2 Although the disease peaks in the fourth decade of life for adults, most pediatric cases are diagnosed between 2 and 14 years of age.14-16

Pathogenesis

Clinical and histopathological data suggest that a complex interaction among the vasculature, extracellular matrix, and immune system plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Similar to scleroderma, the CD4 helper T cell may be involved in the fibrotic changes that occur within these lesions.17 Early in the disease process, TH1 and TH17 inflammatory pathways predominate. The late fibrotic changes seen in scleroderma are more associated with a shift to the TH2 inflammatory pathway.17 Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi has been implicated abroad, but a large-scale study confirming Borrelia as a pathologic factor within morphea lesions has not been completed to date.18-20 Some authors believe early lesions of ECDS mimic erythema chronica migrans, with the late lesions resembling acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.20

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings of morphea tend to vary depending on the stage of the disease. The 2 stages of morphea can be differentiated by the degree of inflammation present histologically.14,21 The early phase of morphea primarily affects the connective and subcutaneous tissue surrounding eccrine sweat glands.14,21 A dense dermal and subcutaneous perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes is commonly observed.5 Later stages of the disease demonstrate densely packed homogenous collagen with minimal inflammation and loss of eccrine glands and blood vessels.14,21 The adipose tissue is generally replaced by sclerotic collagen, giving the biopsy a squared-off appearance.5,14

Management

En coup de sabre presents a treatment challenge. In active lesions, topical or intralesional corticosteroids are considered treatment of choice.5 Methotrexate has proven useful in the treatment of acute and deep forms of linear morphea. A study examining methotrexate in juvenile localized scleroderma, with the majority of patients having the linear subtype, revealed that methotrexate is both efficacious and well tolerated.22 Other reports in the literature reveal efficacy with the use of intravenous corticosteroids and methotrexate combination therapy for treatment of morphea.23,24 A longitudinal prospective study examining the use of high-dose methotrexate and oral corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma yielded positive results, with patients showing clinical improvement within 2 months of initiation of combination therapy.25 Other treatments include excimer laser; calcipotriene and tacrolimus; and surgical approaches such as autologous fat grafting, grafting with muscle flaps, and tissue inserts.21,26-31 In addition, patients can choose to forego therapy, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the ipsilateral scalp and face predominately in children and women. Neurologic involvement is common and should prompt a comprehensive neurologic workup in patients suspected to have ECDS or PHA. Current treatment recommendations include topical, intralesional, and oral corticosteroids; methotrexate; and surgical grafts. Although ECDS is a rare entity, more intensive research is needed on the exact pathophysiology and effective treatment options that focus on improving the cosmetic outcome in these patients. Cosmesis is the primary concern in patients with ECDS and should be managed early and appropriately to prevent long-term psychological sequelae.

En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a unilateral distribution. The lesional skin first exhibits contraction and stiffness that lead to characteristic fibrotic plaques with associated linear alopecia.1 The pansclerotic plaques are ivory in color with hyperpigmented to violaceous borders extending as a paramedian band on the frontoparietal scalp.2,3 The skin lesions bear resemblance to the stroke of the sabre sword, giving the condition its unique name. Many patients initially present with concerns of frontal scalp alopecia.3 Linear morphea, including the ECDS subtype, is predominantly seen in children and women, usually presenting within the first 2 decades of life.1,4

The differential diagnoses of ECDS include focal dermal hypoplasia, steroid atrophy, localized morphea, and lupus profundus.5 En coup de sabre should be distinguished from progressive hemifacial atrophy (PHA)(also known as Parry-Romberg syndrome).6 Progressive hemifacial atrophy presents as unilateral atrophy of the face involving skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and underlying bone in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.1 Both PHA and ECDS exist on a spectrum of linear scleroderma and may coexist in the same patient.6

There is a strong association with extracutaneous neurologic involvement, including seizures, ocular abnormalities, trigeminal neuralgia, and headache.7-10 One study examining ECDS and PHA demonstrated that 44% (19/43) of patients who underwent central nervous system imaging had abnormal findings.11 The majority of patients had magnetic resonance imaging with or without contrast, computed tomography, or both. The most common findings on T2-weighted images were white matter hyperintensities, mostly in subcortical and periventricular regions. The findings were bilateral in 61% (11/18) of patients and ipsilateral to the lesion in 33% (6/18) of patients.11 We present a case of ECDS masquerading as alopecia in a 77-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 77-year-old white woman presented with a chief concern of hair loss on the scalp that had been present since 12 years of age. During her adult life, the scalp lesion remained unchanged with no associated symptoms. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The patient denied any history of seizure disorders, facial paralysis, or neurologic deficits.

Comment

Etiology and Presentation

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear morphea that involves the frontoparietal scalp and forehead.7,12,13 It manifests as a solitary, linear, fibrous plaque that involves the skin, underlying muscle, and bone.7 Although most cases present with a single lesion, multiple lesions can occur.8 The exact etiology of this disease remains to be determined but is characterized by thickening and hardening of the skin secondary to increased collagen production.7 The incidence of linear morphea ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals and is more prevalent in white patients and women.14 Linear morphea is commonly found in children. Children are more likely to have linear morphea on the face, which can lead to lifelong disfigurement.2 Although the disease peaks in the fourth decade of life for adults, most pediatric cases are diagnosed between 2 and 14 years of age.14-16

Pathogenesis

Clinical and histopathological data suggest that a complex interaction among the vasculature, extracellular matrix, and immune system plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Similar to scleroderma, the CD4 helper T cell may be involved in the fibrotic changes that occur within these lesions.17 Early in the disease process, TH1 and TH17 inflammatory pathways predominate. The late fibrotic changes seen in scleroderma are more associated with a shift to the TH2 inflammatory pathway.17 Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi has been implicated abroad, but a large-scale study confirming Borrelia as a pathologic factor within morphea lesions has not been completed to date.18-20 Some authors believe early lesions of ECDS mimic erythema chronica migrans, with the late lesions resembling acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans.20

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings of morphea tend to vary depending on the stage of the disease. The 2 stages of morphea can be differentiated by the degree of inflammation present histologically.14,21 The early phase of morphea primarily affects the connective and subcutaneous tissue surrounding eccrine sweat glands.14,21 A dense dermal and subcutaneous perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes is commonly observed.5 Later stages of the disease demonstrate densely packed homogenous collagen with minimal inflammation and loss of eccrine glands and blood vessels.14,21 The adipose tissue is generally replaced by sclerotic collagen, giving the biopsy a squared-off appearance.5,14

Management

En coup de sabre presents a treatment challenge. In active lesions, topical or intralesional corticosteroids are considered treatment of choice.5 Methotrexate has proven useful in the treatment of acute and deep forms of linear morphea. A study examining methotrexate in juvenile localized scleroderma, with the majority of patients having the linear subtype, revealed that methotrexate is both efficacious and well tolerated.22 Other reports in the literature reveal efficacy with the use of intravenous corticosteroids and methotrexate combination therapy for treatment of morphea.23,24 A longitudinal prospective study examining the use of high-dose methotrexate and oral corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma yielded positive results, with patients showing clinical improvement within 2 months of initiation of combination therapy.25 Other treatments include excimer laser; calcipotriene and tacrolimus; and surgical approaches such as autologous fat grafting, grafting with muscle flaps, and tissue inserts.21,26-31 In addition, patients can choose to forego therapy, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

En coup de sabre is a rare subtype of linear scleroderma that is limited to the ipsilateral scalp and face predominately in children and women. Neurologic involvement is common and should prompt a comprehensive neurologic workup in patients suspected to have ECDS or PHA. Current treatment recommendations include topical, intralesional, and oral corticosteroids; methotrexate; and surgical grafts. Although ECDS is a rare entity, more intensive research is needed on the exact pathophysiology and effective treatment options that focus on improving the cosmetic outcome in these patients. Cosmesis is the primary concern in patients with ECDS and should be managed early and appropriately to prevent long-term psychological sequelae.

1. Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:62-73.

2. Picket AJ, Carpentieri D, Price H, et al. Early morphea mimicking acquired port-wine stain. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:591-594.

3. Holland KE, Steffes B, Nocton JJ, et al. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre with associated neurologic abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2006;117:132-136.

4. Goh C, Biswas A, Goldberg LJ. Alopecia with perineural lymphocytes: a clue to linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:518-520.

5. Kreuter A. Localized scleroderma. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:135-147.

6. Tolkachjov SN, Patel NG, Tollefson MM. Progressive hemifacial atrophy: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:39.

7. Amaral TN, Marques Neto JF, Lapa AT, et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma en coup de sabre [published online January 27, 2012]. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:719685.

8. Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de sabre morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: a retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:257-263.

9. Zannin ME, Martini G, Athreya BH, et al. Ocular involvement in children with localized scleroderma: a multi-center study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1311-1314.

10. Polcari I, Moon A, Mathes EF, et al. Headaches as a presenting symptom of linear morphea en coup de sabre. Pediatrics. 2014;134:1715-1719.

11. Doolittle DA, Lehman VT, Schwartz KM, et al. CNS imaging findings associated with Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre: correlation to dermatologic and neurologic abnormalities. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:21-34.

12. Pierre-Louis M, Sperling LC, Wilke MS, et al. Distinctive histopathologic findings in linear morphea (en coup de sabre) alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:580-584.

13. Thareja SK, Sadhwani D, Alan Fenske N. En coup de sabre morphea treated with hyaluronic acid filler. Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:823-826.

14. Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

15. Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:385-396.

16. Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW, et al. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:545-550.

17. Kurzinski K, Torok KS. Cytokine profiles in localized scleroderma and relationship to clinical features. Cytokine. 2011;55:157-164.

18. Eisendle K, Grabner T, Zelger B. Morphoea: a manifestation of infection with Borrelia species? Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1189-1198.

19. Gutiérrez-Gómez C, Godínez-Hana AL, García-Hernández M, et al. Lack of IgG antibody seropositivity to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Parry-Romberg syndrome and linear morphea en coup de sabre in Mexico. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:947-951.

20. Miller K, Lehrhoff S, Fischer M, et al. Linear morphea of the forehead (en coup de sabre). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:22.

21. Hanson AH, Fivenson DP, Schapiro B. Linear scleroderma in an adolescent woman treated with methotrexate and excimer laser. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:203-205.

22. Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, et al. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1998-2006.

23. Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate in severe localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:847-852.

24. Weibel L, Sampaio MC, Visentin MT, et al. Evaluation of methotrexate and corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma (morphoea) in children. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1013-1020.

25. Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:286-294.

26. Nisticò SP, Saraceno R, Schipani C, et al. Different applications of monochromatic excimer light in skin diseases. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27:647-654.

27. Zwischenberger BA, Jacobe HT. A systematic review of morphea treatments and therapeutic algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:925-941.

28. Karaaltin MV, Akpinar AC, Baghaki S, et al. Treatment of “en coup de sabre” deformity with adipose-derived regenerative cell-enriched fat graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:103-105.

29. Consorti G, Tieghi R, Clauser LC. Frontal linear scleroderma: long-term result in volumetric restoration of the fronto-orbital area by structural fat grafting. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:263-265.

30. Cavusoglu T, Yazici I, Vargel I, et al. Reconstruction of coup de sabre deformity (linear localized scleroderma) by using galeal frontalis muscle flap and demineralized bone matrix combination. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:257-258.

31. Robitschek J, Wang D, Hall D. Treatment of linear scleroderma “en coup de sabre” with AlloDerm tissue matrix. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:540-541.

1. Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:62-73.

2. Picket AJ, Carpentieri D, Price H, et al. Early morphea mimicking acquired port-wine stain. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:591-594.

3. Holland KE, Steffes B, Nocton JJ, et al. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre with associated neurologic abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2006;117:132-136.

4. Goh C, Biswas A, Goldberg LJ. Alopecia with perineural lymphocytes: a clue to linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:518-520.

5. Kreuter A. Localized scleroderma. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:135-147.

6. Tolkachjov SN, Patel NG, Tollefson MM. Progressive hemifacial atrophy: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:39.

7. Amaral TN, Marques Neto JF, Lapa AT, et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma en coup de sabre [published online January 27, 2012]. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:719685.

8. Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de sabre morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: a retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:257-263.

9. Zannin ME, Martini G, Athreya BH, et al. Ocular involvement in children with localized scleroderma: a multi-center study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1311-1314.

10. Polcari I, Moon A, Mathes EF, et al. Headaches as a presenting symptom of linear morphea en coup de sabre. Pediatrics. 2014;134:1715-1719.

11. Doolittle DA, Lehman VT, Schwartz KM, et al. CNS imaging findings associated with Parry-Romberg syndrome and en coup de sabre: correlation to dermatologic and neurologic abnormalities. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:21-34.

12. Pierre-Louis M, Sperling LC, Wilke MS, et al. Distinctive histopathologic findings in linear morphea (en coup de sabre) alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:580-584.

13. Thareja SK, Sadhwani D, Alan Fenske N. En coup de sabre morphea treated with hyaluronic acid filler. Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:823-826.

14. Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

15. Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:385-396.

16. Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW, et al. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:545-550.

17. Kurzinski K, Torok KS. Cytokine profiles in localized scleroderma and relationship to clinical features. Cytokine. 2011;55:157-164.

18. Eisendle K, Grabner T, Zelger B. Morphoea: a manifestation of infection with Borrelia species? Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1189-1198.

19. Gutiérrez-Gómez C, Godínez-Hana AL, García-Hernández M, et al. Lack of IgG antibody seropositivity to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Parry-Romberg syndrome and linear morphea en coup de sabre in Mexico. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:947-951.

20. Miller K, Lehrhoff S, Fischer M, et al. Linear morphea of the forehead (en coup de sabre). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:22.

21. Hanson AH, Fivenson DP, Schapiro B. Linear scleroderma in an adolescent woman treated with methotrexate and excimer laser. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:203-205.

22. Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, et al. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1998-2006.

23. Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate in severe localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:847-852.

24. Weibel L, Sampaio MC, Visentin MT, et al. Evaluation of methotrexate and corticosteroids for the treatment of localized scleroderma (morphoea) in children. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1013-1020.

25. Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:286-294.

26. Nisticò SP, Saraceno R, Schipani C, et al. Different applications of monochromatic excimer light in skin diseases. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27:647-654.

27. Zwischenberger BA, Jacobe HT. A systematic review of morphea treatments and therapeutic algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:925-941.

28. Karaaltin MV, Akpinar AC, Baghaki S, et al. Treatment of “en coup de sabre” deformity with adipose-derived regenerative cell-enriched fat graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:103-105.

29. Consorti G, Tieghi R, Clauser LC. Frontal linear scleroderma: long-term result in volumetric restoration of the fronto-orbital area by structural fat grafting. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:263-265.

30. Cavusoglu T, Yazici I, Vargel I, et al. Reconstruction of coup de sabre deformity (linear localized scleroderma) by using galeal frontalis muscle flap and demineralized bone matrix combination. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:257-258.

31. Robitschek J, Wang D, Hall D. Treatment of linear scleroderma “en coup de sabre” with AlloDerm tissue matrix. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:540-541.

Practice Points

• En coup de sabre (ECDS) is a rare subtype of linear

scleroderma that is limited to the hemiface in a

unilateral distribution.

• Neurologic involvement is common and should

prompt a comprehensive neurologic workup in

patients suspected to have ECDS or progressive

hemiface atrophy.

• Corticosteroids remain the treatment of choice, but

other modalities such as methotrexate, excimer laser,

and grafting have been used with varying success.