User login

Cat Scratch Disease Presenting With Concurrent Pityriasis Rosea in a 10-Year-Old Girl

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should familiarize themselves with the physical examination findings of cat scratch disease.

- There are numerous clinical variants and triggers of pityriasis rosea (PR).

- There may be a new infectious trigger for PR, and exposure to cats prior to a classic PR eruption should raise one’s suspicion as a possible cause.

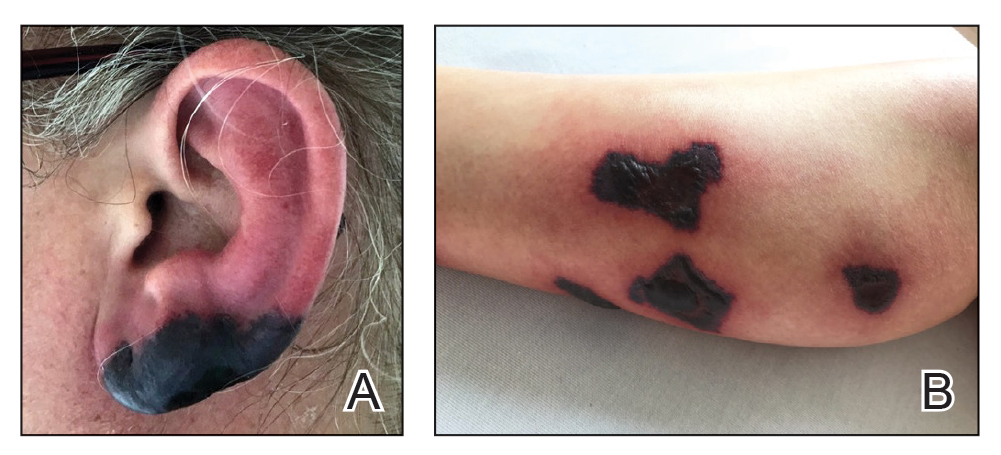

Bullous Retiform Purpura on the Ears and Legs

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

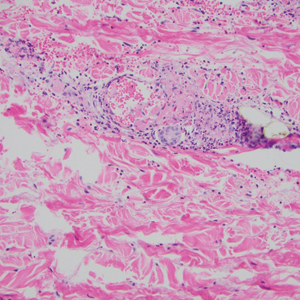

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

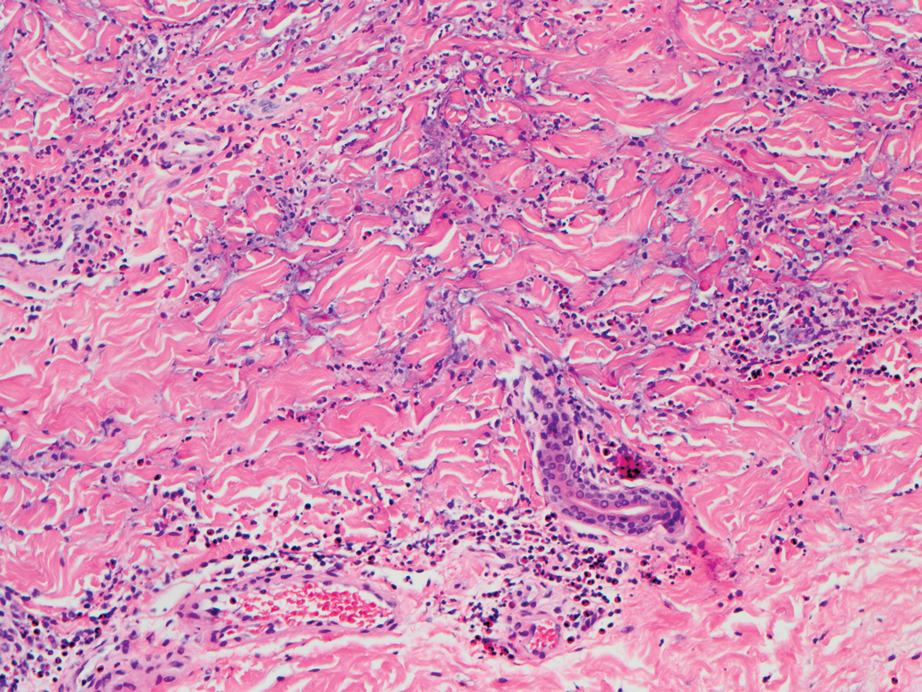

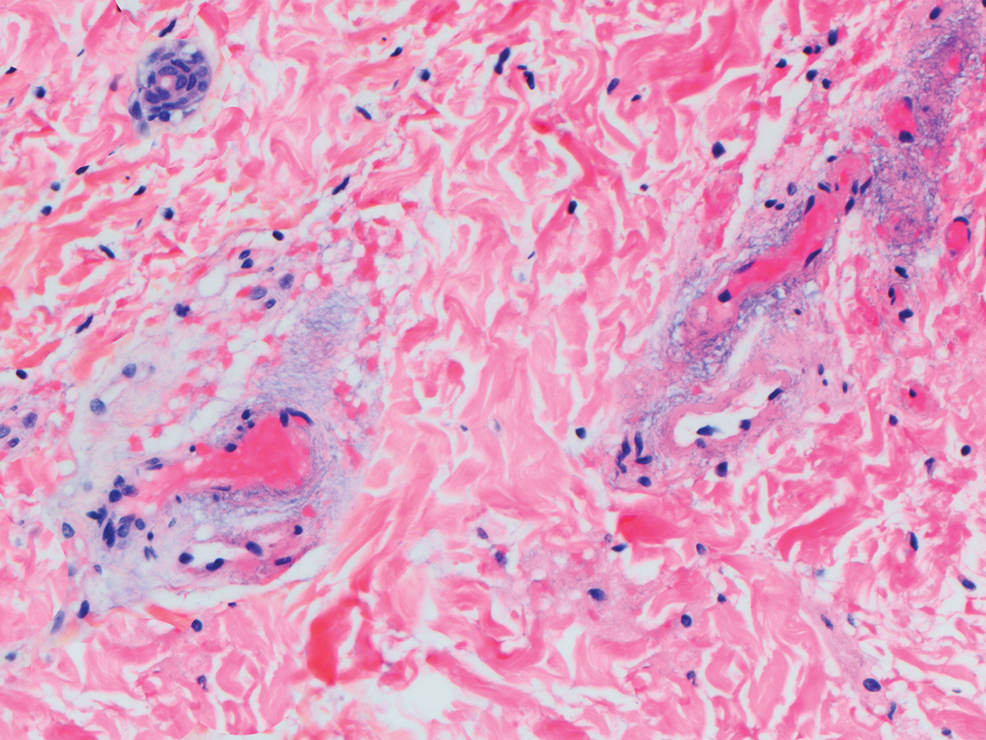

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

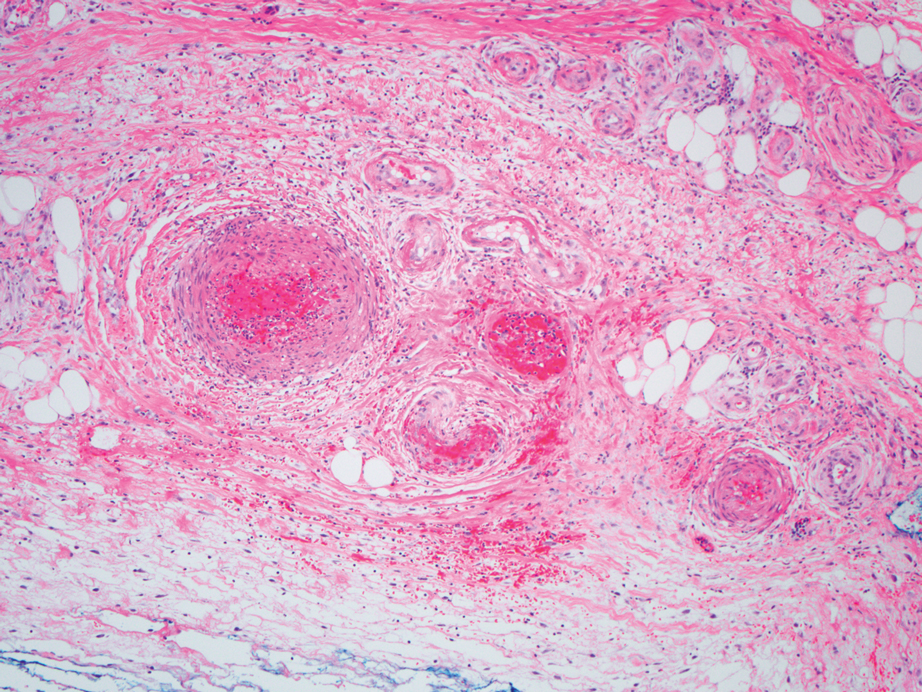

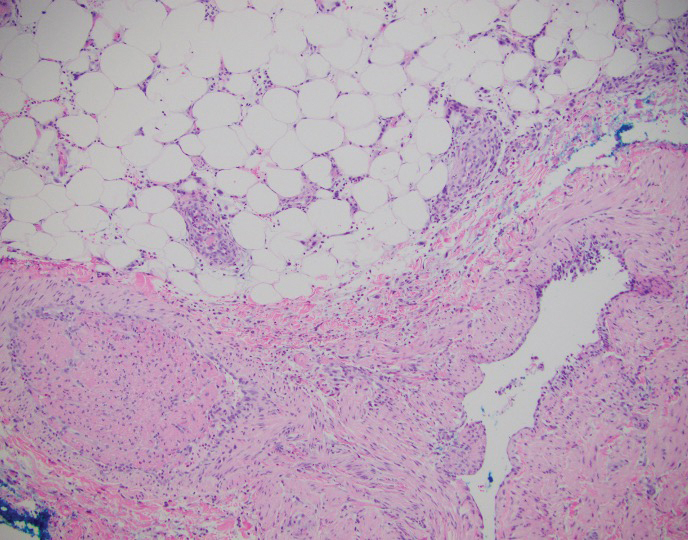

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

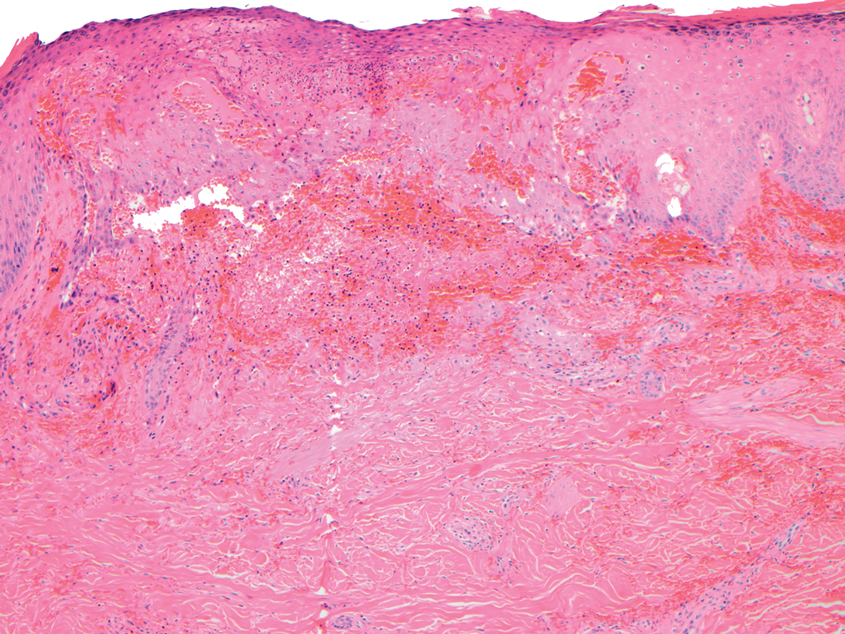

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

A 40-year-old woman presented with a progressive painful rash on the ears and legs of 2 weeks’ duration. She described the rash as initially red and nonpainful; it started on the right leg and progressed to the left leg, eventually involving the earlobes 4 days prior to presentation. Physical examination revealed edematous purpura of the earlobes and bullous retiform purpura on the lower extremities. Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia (3.6×103 /cm2 [reference range, 4.0–10.5×103 /cm2 ]) and elevated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (1:320 titer [reference range, <1:40]) in a perinuclear pattern (perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies). Urine toxicology screening was positive for cocaine and opiates. A punch biopsy of a bullous retiform purpura on the right thigh was obtained for standard hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Rapidly developing vesicular eruption

A 23-month-old girl with a history of well-controlled atopic dermatitis was admitted to the hospital with fever and a widespread vesicular eruption of 2 days’ duration. Two days prior to admission, the patient had 3 episodes of nonbloody diarrhea and redness in the diaper area. The child’s parents reported that the red areas spread to her arms and legs later that day, and that she subsequently developed a fever, cough, and rhinorrhea. She was taken to an urgent care facility where she was diagnosed with vulvovaginitis and an upper respiratory infection; amoxicillin was prescribed. Shortly thereafter, the patient developed more lesions in and around the mouth, as well as on the trunk, prompting the parents to bring her to the emergency department.

The history revealed that the patient had spent time with her aunt and cousins who had “red spots” on their palms and soles. The patient’s sister had a flare of “cold sores,” about 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. The patient had received a varicella zoster virus (VZV) vaccine several months earlier.

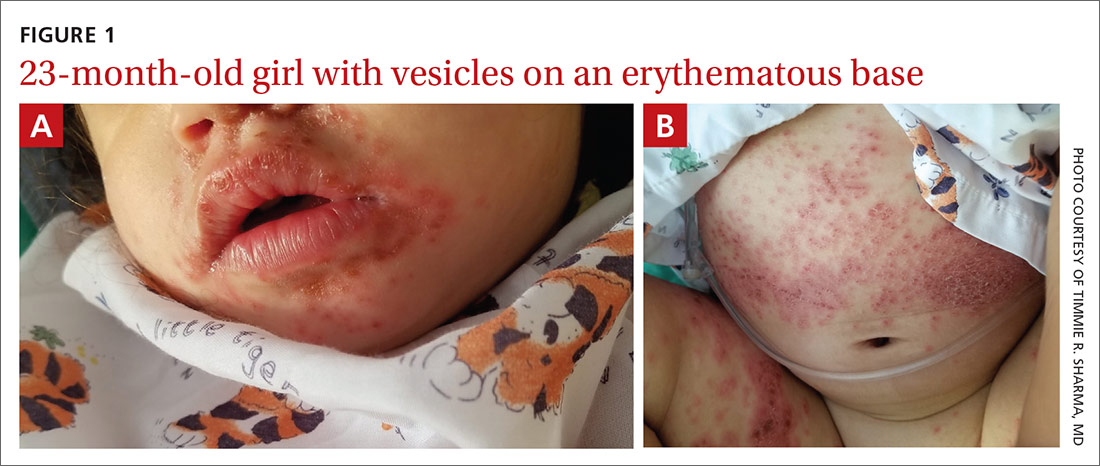

Physical examination was notable for an uncomfortable infant with erythematous macules on the bilateral palms and soles and an erythematous hard palate. The child also had scattered vesicles on an erythematous base with confluent crusted plaques on her lips, perioral skin (FIGURE 1A), abdomen, back, buttocks, arms, legs (FIGURE 1B), and dorsal aspects of her hands and feet.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema coxsackium

Given the history of atopic dermatitis; prodromal diarrhea/rhinorrhea; papulovesicular eruption involving areas of prior dermatitis as well as the palms, soles, and mouth; recent contacts with suspected hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD); and history of VZV vaccination, the favored diagnosis was eczema coxsackium.

Eczema coxsackium is an atypical form of HFMD that occurs in patients with a history of eczema. Classic HFMD usually is caused by coxsackievirus A16 or enterovirus 71, while atypical HFMD often is caused by coxsackievirus A6.1,2,3 Patients with HFMD present with painful oral vesicles and ulcers and a papulovesicular eruption on the palms, soles, and sometimes the buttocks and genitalia. Patients may have prodromal fever, fussiness, and diarrhea. Painful oral lesions may result in poor oral intake.1,2

Differential includes viral eruptions

Other conditions may manifest similarly to eczema coxsackium and must be ruled out before initiating proper treatment.

Eczema herpeticum (EH). In atypical HFMD, the virus can show tropism for active or previously inflamed areas of eczematous skin, leading to a widespread vesicular eruption, which can be difficult to distinguish from EH.1 Similar to EH, eczema coxsackium does not exclusively affect children with atopic dermatitis. It also has been described in adults and patients with Darier disease, incontinentia pigmenti, and epidermolytic ichthyosis.4-6

In cases of vesicular eruptions in eczema patients, it is imperative to rule out EH. One prospective study of atypical HFMD compared similarities of the conditions. Both have a predilection for mucosa during primary infection and develop vesicular eruptions on cutaneous eczematous skin.1 One key difference between eczema coxsackium and EH is that EH tends to produce intraoral vesicles beyond simple erythema; it also tends to predominate in the area of the head and neck.7

Continue to: Eczema varicellicum

Eczema varicellicum has been reported, and it has been suggested that some cases of EH may actually be caused by VZV as the 2 are clinically indistinguishable and less than half of EH cases are diagnosed with laboratory confirmation.8

Confirm Dx before you treat

To guide management, cases of suspected eczema coxsackium should be confirmed, and HSV/VZV should be ruled out.9 Testing modalities include swabbing vesicular fluid for enterovirus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis (preferred modality), oropharyngeal swab up to 2 weeks after infection, or viral isolate from stool samples up to 3 months after infection.2,3

Treatment for eczema coxsackium involves supportive care such as intravenous (IV) hydration and antipyretics. Some studies show potential benefit with IV immunoglobulin in treating severe HFMD, while other studies show the exacerbation of widespread HFMD with this treatment.7,10

Prompt diagnosis and treatment for eczema coxsackium is critical to prevent unnecessary antiviral therapy and to help guide monitoring for associated morbidities including Gianotti-Crosti syndrome–like eruptions, purpuric eruptions, and onychomadesis.

Our patient. Because EH was in the differential, our patient was started on empiric IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours while test results were pending. In addition, she received acetaminophen, IV fluids, gentle sponge baths, and diligent emollient application. Scraping from a vesicle revealed negative herpes simplex virus 1/2 PCR, negative VZV direct fluorescent antibody, and a positive enterovirus PCR—confirming the diagnosis of eczema coxsackium. Interestingly, a viral culture was negative in our patient, consistent with prior reports of enterovirus being difficult to culture.11

With confirmation of the diagnosis of eczema coxsackium, the IV acyclovir was discontinued, and symptoms resolved after 7 days.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shane M. Swink, DO, MS, Division of Dermatology, 1200 South Cedar Crest Boulevard, Allentown, PA 18103; shanesw@pcom.edu

1. Neri I, Dondi A, Wollenberg A, et al. Atypical forms of hand, foot, and mouth disease: a prospective study of 47 Italian children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:429-437.

2. Nassef C, Ziemer C, Morrell DS. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease: a new look at a classic viral rash. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:486-491.

3. Horsten H, Fisker N, Bygu, A. Eczema coxsackium caused by coxsackievirus A6. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:230-231.

4. Jefferson J, Grossberg A. Incontinentia pigmenti coxsackium. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E280-E281.

5. Ganguly S, Kuruvila S. Eczema coxsackium. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:682-683.

6. Harris P, Wang AD, Yin M, et al. Atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease: eczema coxsackium can also occur in adults. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1043.

7. Wollenberg A, Zoch C, Wetzel S, et al. Predisposing factors and clinical features of eczema herpeticum: a retrospective analysis of 100 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:198-205.

8. Austin TA, Steele RW. Eczema varicella/zoster (varicellicum). Clin Pediatr. 2017;56:579-581.

9. Leung DYM. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

10. Cao RY, Dong DY, Liu RJ, et al. Human IgG subclasses against enterovirus type 71: neutralization versus antibody dependent enhancement of infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:E64024.

11. Mathes EF, Oza V, Frieden IJ, et al. Eczema coxsackium and unusual cutaneous findings in an enterovirus outbreak. Pediatrics. 2013;132:149-157.

A 23-month-old girl with a history of well-controlled atopic dermatitis was admitted to the hospital with fever and a widespread vesicular eruption of 2 days’ duration. Two days prior to admission, the patient had 3 episodes of nonbloody diarrhea and redness in the diaper area. The child’s parents reported that the red areas spread to her arms and legs later that day, and that she subsequently developed a fever, cough, and rhinorrhea. She was taken to an urgent care facility where she was diagnosed with vulvovaginitis and an upper respiratory infection; amoxicillin was prescribed. Shortly thereafter, the patient developed more lesions in and around the mouth, as well as on the trunk, prompting the parents to bring her to the emergency department.

The history revealed that the patient had spent time with her aunt and cousins who had “red spots” on their palms and soles. The patient’s sister had a flare of “cold sores,” about 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. The patient had received a varicella zoster virus (VZV) vaccine several months earlier.

Physical examination was notable for an uncomfortable infant with erythematous macules on the bilateral palms and soles and an erythematous hard palate. The child also had scattered vesicles on an erythematous base with confluent crusted plaques on her lips, perioral skin (FIGURE 1A), abdomen, back, buttocks, arms, legs (FIGURE 1B), and dorsal aspects of her hands and feet.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema coxsackium

Given the history of atopic dermatitis; prodromal diarrhea/rhinorrhea; papulovesicular eruption involving areas of prior dermatitis as well as the palms, soles, and mouth; recent contacts with suspected hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD); and history of VZV vaccination, the favored diagnosis was eczema coxsackium.

Eczema coxsackium is an atypical form of HFMD that occurs in patients with a history of eczema. Classic HFMD usually is caused by coxsackievirus A16 or enterovirus 71, while atypical HFMD often is caused by coxsackievirus A6.1,2,3 Patients with HFMD present with painful oral vesicles and ulcers and a papulovesicular eruption on the palms, soles, and sometimes the buttocks and genitalia. Patients may have prodromal fever, fussiness, and diarrhea. Painful oral lesions may result in poor oral intake.1,2

Differential includes viral eruptions

Other conditions may manifest similarly to eczema coxsackium and must be ruled out before initiating proper treatment.

Eczema herpeticum (EH). In atypical HFMD, the virus can show tropism for active or previously inflamed areas of eczematous skin, leading to a widespread vesicular eruption, which can be difficult to distinguish from EH.1 Similar to EH, eczema coxsackium does not exclusively affect children with atopic dermatitis. It also has been described in adults and patients with Darier disease, incontinentia pigmenti, and epidermolytic ichthyosis.4-6

In cases of vesicular eruptions in eczema patients, it is imperative to rule out EH. One prospective study of atypical HFMD compared similarities of the conditions. Both have a predilection for mucosa during primary infection and develop vesicular eruptions on cutaneous eczematous skin.1 One key difference between eczema coxsackium and EH is that EH tends to produce intraoral vesicles beyond simple erythema; it also tends to predominate in the area of the head and neck.7

Continue to: Eczema varicellicum

Eczema varicellicum has been reported, and it has been suggested that some cases of EH may actually be caused by VZV as the 2 are clinically indistinguishable and less than half of EH cases are diagnosed with laboratory confirmation.8

Confirm Dx before you treat

To guide management, cases of suspected eczema coxsackium should be confirmed, and HSV/VZV should be ruled out.9 Testing modalities include swabbing vesicular fluid for enterovirus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis (preferred modality), oropharyngeal swab up to 2 weeks after infection, or viral isolate from stool samples up to 3 months after infection.2,3

Treatment for eczema coxsackium involves supportive care such as intravenous (IV) hydration and antipyretics. Some studies show potential benefit with IV immunoglobulin in treating severe HFMD, while other studies show the exacerbation of widespread HFMD with this treatment.7,10

Prompt diagnosis and treatment for eczema coxsackium is critical to prevent unnecessary antiviral therapy and to help guide monitoring for associated morbidities including Gianotti-Crosti syndrome–like eruptions, purpuric eruptions, and onychomadesis.

Our patient. Because EH was in the differential, our patient was started on empiric IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours while test results were pending. In addition, she received acetaminophen, IV fluids, gentle sponge baths, and diligent emollient application. Scraping from a vesicle revealed negative herpes simplex virus 1/2 PCR, negative VZV direct fluorescent antibody, and a positive enterovirus PCR—confirming the diagnosis of eczema coxsackium. Interestingly, a viral culture was negative in our patient, consistent with prior reports of enterovirus being difficult to culture.11

With confirmation of the diagnosis of eczema coxsackium, the IV acyclovir was discontinued, and symptoms resolved after 7 days.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shane M. Swink, DO, MS, Division of Dermatology, 1200 South Cedar Crest Boulevard, Allentown, PA 18103; shanesw@pcom.edu

A 23-month-old girl with a history of well-controlled atopic dermatitis was admitted to the hospital with fever and a widespread vesicular eruption of 2 days’ duration. Two days prior to admission, the patient had 3 episodes of nonbloody diarrhea and redness in the diaper area. The child’s parents reported that the red areas spread to her arms and legs later that day, and that she subsequently developed a fever, cough, and rhinorrhea. She was taken to an urgent care facility where she was diagnosed with vulvovaginitis and an upper respiratory infection; amoxicillin was prescribed. Shortly thereafter, the patient developed more lesions in and around the mouth, as well as on the trunk, prompting the parents to bring her to the emergency department.

The history revealed that the patient had spent time with her aunt and cousins who had “red spots” on their palms and soles. The patient’s sister had a flare of “cold sores,” about 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. The patient had received a varicella zoster virus (VZV) vaccine several months earlier.

Physical examination was notable for an uncomfortable infant with erythematous macules on the bilateral palms and soles and an erythematous hard palate. The child also had scattered vesicles on an erythematous base with confluent crusted plaques on her lips, perioral skin (FIGURE 1A), abdomen, back, buttocks, arms, legs (FIGURE 1B), and dorsal aspects of her hands and feet.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema coxsackium

Given the history of atopic dermatitis; prodromal diarrhea/rhinorrhea; papulovesicular eruption involving areas of prior dermatitis as well as the palms, soles, and mouth; recent contacts with suspected hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD); and history of VZV vaccination, the favored diagnosis was eczema coxsackium.

Eczema coxsackium is an atypical form of HFMD that occurs in patients with a history of eczema. Classic HFMD usually is caused by coxsackievirus A16 or enterovirus 71, while atypical HFMD often is caused by coxsackievirus A6.1,2,3 Patients with HFMD present with painful oral vesicles and ulcers and a papulovesicular eruption on the palms, soles, and sometimes the buttocks and genitalia. Patients may have prodromal fever, fussiness, and diarrhea. Painful oral lesions may result in poor oral intake.1,2

Differential includes viral eruptions

Other conditions may manifest similarly to eczema coxsackium and must be ruled out before initiating proper treatment.

Eczema herpeticum (EH). In atypical HFMD, the virus can show tropism for active or previously inflamed areas of eczematous skin, leading to a widespread vesicular eruption, which can be difficult to distinguish from EH.1 Similar to EH, eczema coxsackium does not exclusively affect children with atopic dermatitis. It also has been described in adults and patients with Darier disease, incontinentia pigmenti, and epidermolytic ichthyosis.4-6

In cases of vesicular eruptions in eczema patients, it is imperative to rule out EH. One prospective study of atypical HFMD compared similarities of the conditions. Both have a predilection for mucosa during primary infection and develop vesicular eruptions on cutaneous eczematous skin.1 One key difference between eczema coxsackium and EH is that EH tends to produce intraoral vesicles beyond simple erythema; it also tends to predominate in the area of the head and neck.7

Continue to: Eczema varicellicum

Eczema varicellicum has been reported, and it has been suggested that some cases of EH may actually be caused by VZV as the 2 are clinically indistinguishable and less than half of EH cases are diagnosed with laboratory confirmation.8

Confirm Dx before you treat

To guide management, cases of suspected eczema coxsackium should be confirmed, and HSV/VZV should be ruled out.9 Testing modalities include swabbing vesicular fluid for enterovirus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis (preferred modality), oropharyngeal swab up to 2 weeks after infection, or viral isolate from stool samples up to 3 months after infection.2,3

Treatment for eczema coxsackium involves supportive care such as intravenous (IV) hydration and antipyretics. Some studies show potential benefit with IV immunoglobulin in treating severe HFMD, while other studies show the exacerbation of widespread HFMD with this treatment.7,10

Prompt diagnosis and treatment for eczema coxsackium is critical to prevent unnecessary antiviral therapy and to help guide monitoring for associated morbidities including Gianotti-Crosti syndrome–like eruptions, purpuric eruptions, and onychomadesis.