User login

Sweet Syndrome With Marked Eosinophilic Infiltrate

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is an uncommon inflammatory skin disorder characterized by sudden onset of fever, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and tender erythematous papules or plaques or both. Skin biopsy usually reveals extensive infiltration of neutrophils into the epidermis and dermis.1-3 Although rare, cases of eosinophil-rich SS have been reported in patients with drug-induced and malignancy-associated SS.4,5 We report a case of a patient with classical SS with dermal eosinophilic infiltration.

An 80-year-old Hispanic man presented with abrupt onset of a rash on the posterior scalp, left ear, back, and hands of 5 days’ duration. The lesions were painful and had progressed to the point of impairing hand grip. The patient’s medical history included a reported common cold the week prior, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, for which he took metoprolol, simvastatin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. He denied oral lesions and medication changes. He was afebrile and did not experience dietary changes, weight loss, or fatigue. He recently returned from travel to the Dominican Republic.

Physical examination revealed tender, well demarcated, pink to violaceous, pseudovesicular papules and plaques on the palms and dorsal hands (Figure 1), the posterior scalp, left ear, proximal left arm, and back. Pink, juicy, targetoid papules were also found on the scalp, back, and left arm. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Laboratory test results revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,500/µL [reference range, 3800-10,800/µL]), absolute neutrophil count (8073/µL [reference range, 1500–7800/µL]), and eosinophil count (610/µL [reference range, 15–500/µL]). These results indicated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and mild eosinophilia. The patient also was anemic (hemoglobin, 11.5 g/dL [reference range, 13.2–17.1 g/dL]; hematocrit, 35.1% [reference range, 38.5%–50%]). Urine testing revealed altered renal function (serum creatinine, 2.42 mg/dL [reference range, 0.7–1.1 mg/dL]; blood urea nitrogen, 34 mg/dL [reference range, 7–25 mg/dL]; glomerular filtration rate, 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2]), suggesting stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Urinalysis showed mild hematuria and proteinuria.

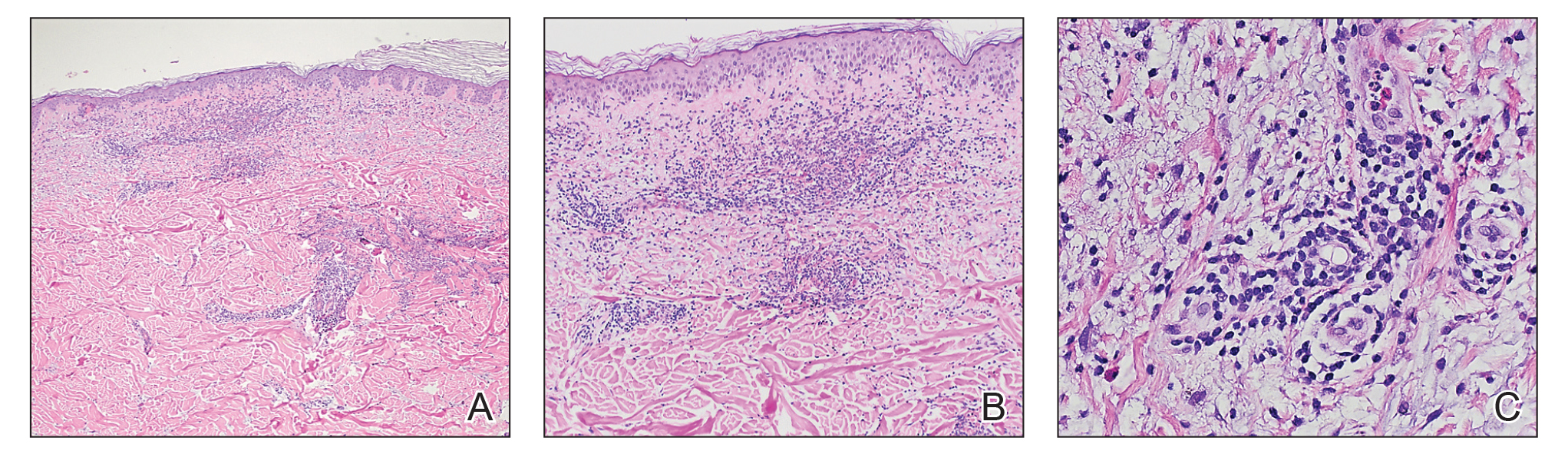

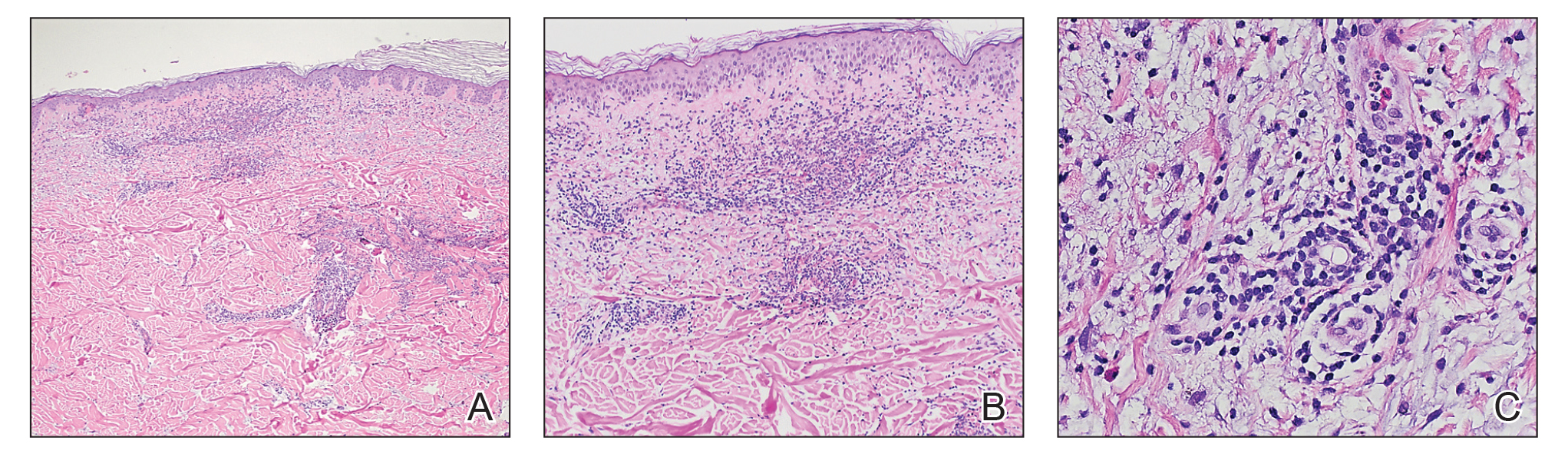

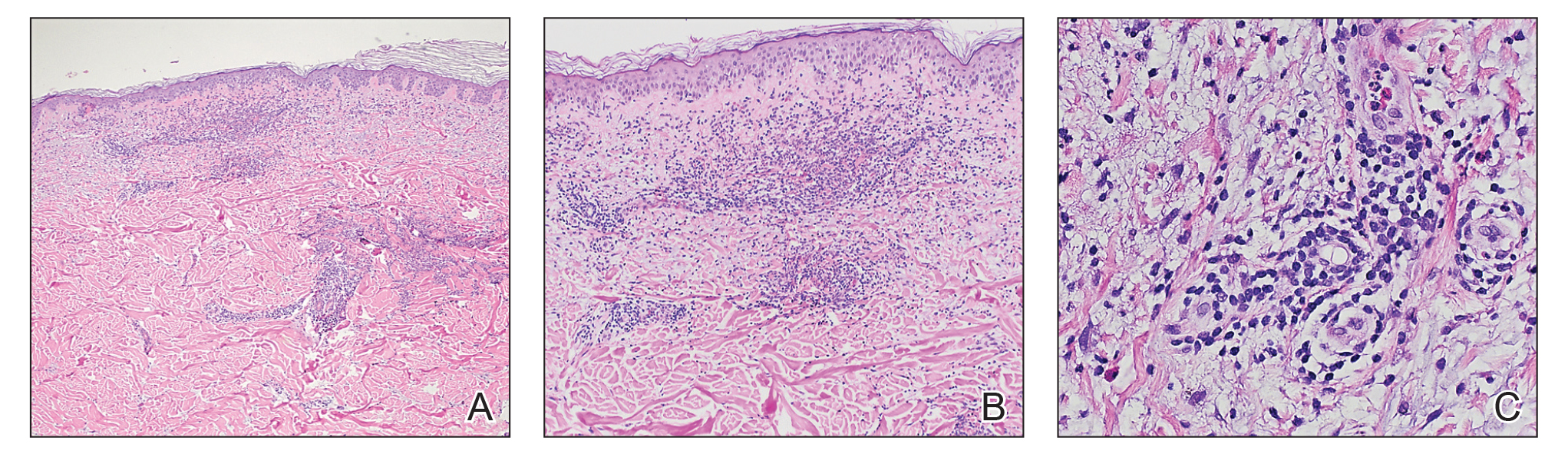

Histopathology of biopsies taken from plaques on the left arm and lower back revealed a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with numerous scattered eosinophils in the dermis. Some neutrophils were intact; others were fragmented without evidence of vasculitis. A subtle subepidermal edema also was noted (Figure 2). A diagnosis of SS was made.

Initial treatment included prednisone (40 mg daily, tapered by 5 mg every 3 days) and erythromycin (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days because of suspected Mycoplasma infection. The rash resolved in 1 week. No recurrence was noted during 4 months of follow-up. The white blood cell count returned to within reference range (8400/µL), ruling out the possibility of a smoldering myeloid process.

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis was first described in a case series of 8 women by Sweet6 in 1964. Patients typically present first with fever, which can precede cutaneous symptoms for days or weeks. Skin lesions generally are asymmetric and located on the face, neck, and upper extremities. Lesions can be described as painful, purple to red papules, plaques, or nodules. Sweet syndrome can present as 3 subtypes based on cause7: (1) classical SS, also known as idiopathic SS, can be preceded by an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract infection or vaccination, or can be pregnancy associated2; (2) drug-induced SS usually follows use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, or other causative drugs including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, quinolones, oral contraceptives, furosemide, hydralazine, diazepam, clozapine, abacavir, imatinib, bortezomib, azathioprine, and celecoxib2,3,8; and (3) malignancy-associated SS can occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome and generally is associated with hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor.1,9

In our patient, the observed clinical and histological findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SS,2,10 specifically tender erythematous plaques of sudden onset, fast response to systemic corticosteroid therapy, a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and leukocytosis greater than 8000/µL with more than 70% neutrophils. He also exhibited targetoid lesions, which have been reported in 7% to 12% of SS patients.10,11

The predominant cells involved in the dermis of SS lesions are mature neutrophils; however, eosinophils have been observed in small numbers within dermal infiltrates in skin lesions of patients with either classical SS or drug-induced dermatosis.2 In 2 studies of cases of SS (N=73 and N=31), eosinophils were reported in 35% and 41% of skin biopsies, respectively.4,5 Nevertheless, cases with dense eosinophilic infiltrates are rare. Furthermore, Masuda et al12 reported a case of eosinophil-rich SS in a 29-year-old woman after treatment of an upper respiratory tract infection with an antibiotic, and Soon et al13 described an eosinophil-rich case of SS in the setting of new-onset enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Our patient was considered to have classical SS because he had an episode of an upper respiratory tract infection 1 week prior to onset of clinical manifestations. The histologic finding of numerous eosinophils in our case was unusual for idiopathic SS. This finding might suggest a drug hypersensitivity reaction, but the lack of any change in the patient’s long-term medication list and the lack of any other episodes made a diagnosis of drug-induced SS less likely in our patient.

Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is a rare cutaneous condition in which nodules, pruritic papules, and vesicles arise in patients with a hematologic malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma,13 in which a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and numerous eosinophils are observed. Malignancy was ruled out in our patient because of the lack of characteristic abnormalities in blood testing, the fast response to corticosteroid therapy, and the lack of recurrence posttreatment or additional systemic concerns.

The typical pathology findings of SS consist of mature neutrophils found in the dermis without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Eosinophil-rich infiltration, however rare, has been reported in SS. This report highlights a case of classical SS with a particularly dense eosinophilic infiltrate, which could be mistaken for other eosinophilic dermatoses. Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of marked eosinophilic infiltration in all subtypes of this disorder.

- Herbert-Cohen D, Jour G, Saul T. Sweet’s syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:e95-e97.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378.

- Rochael MC, Pantaleão L, Vilar EA, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: study of 73 cases, emphasizing histopathological findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:702-707.

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Polimeni G, Cardillo R, Garaffo E, et al. Allopurinol-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:329-332.

- Paydas S. Sweet’s syndrome: a revisit for hematologists and oncologists. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;86:85-95.

- Amouri M, Masmoudi A, Ammar M, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: a retrospective study of 90 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1033-1039.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Masuda T, Abe Y, Arata J, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) associated with extreme infiltration of eosinophils. J Dermatol. 1994;21:341-346.

- Soon CW, Kirsch IR, Connolly AJ, et al. Eosinophil-rich acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in a patient with enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, type 1. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:704-708.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is an uncommon inflammatory skin disorder characterized by sudden onset of fever, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and tender erythematous papules or plaques or both. Skin biopsy usually reveals extensive infiltration of neutrophils into the epidermis and dermis.1-3 Although rare, cases of eosinophil-rich SS have been reported in patients with drug-induced and malignancy-associated SS.4,5 We report a case of a patient with classical SS with dermal eosinophilic infiltration.

An 80-year-old Hispanic man presented with abrupt onset of a rash on the posterior scalp, left ear, back, and hands of 5 days’ duration. The lesions were painful and had progressed to the point of impairing hand grip. The patient’s medical history included a reported common cold the week prior, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, for which he took metoprolol, simvastatin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. He denied oral lesions and medication changes. He was afebrile and did not experience dietary changes, weight loss, or fatigue. He recently returned from travel to the Dominican Republic.

Physical examination revealed tender, well demarcated, pink to violaceous, pseudovesicular papules and plaques on the palms and dorsal hands (Figure 1), the posterior scalp, left ear, proximal left arm, and back. Pink, juicy, targetoid papules were also found on the scalp, back, and left arm. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Laboratory test results revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,500/µL [reference range, 3800-10,800/µL]), absolute neutrophil count (8073/µL [reference range, 1500–7800/µL]), and eosinophil count (610/µL [reference range, 15–500/µL]). These results indicated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and mild eosinophilia. The patient also was anemic (hemoglobin, 11.5 g/dL [reference range, 13.2–17.1 g/dL]; hematocrit, 35.1% [reference range, 38.5%–50%]). Urine testing revealed altered renal function (serum creatinine, 2.42 mg/dL [reference range, 0.7–1.1 mg/dL]; blood urea nitrogen, 34 mg/dL [reference range, 7–25 mg/dL]; glomerular filtration rate, 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2]), suggesting stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Urinalysis showed mild hematuria and proteinuria.

Histopathology of biopsies taken from plaques on the left arm and lower back revealed a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with numerous scattered eosinophils in the dermis. Some neutrophils were intact; others were fragmented without evidence of vasculitis. A subtle subepidermal edema also was noted (Figure 2). A diagnosis of SS was made.

Initial treatment included prednisone (40 mg daily, tapered by 5 mg every 3 days) and erythromycin (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days because of suspected Mycoplasma infection. The rash resolved in 1 week. No recurrence was noted during 4 months of follow-up. The white blood cell count returned to within reference range (8400/µL), ruling out the possibility of a smoldering myeloid process.

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis was first described in a case series of 8 women by Sweet6 in 1964. Patients typically present first with fever, which can precede cutaneous symptoms for days or weeks. Skin lesions generally are asymmetric and located on the face, neck, and upper extremities. Lesions can be described as painful, purple to red papules, plaques, or nodules. Sweet syndrome can present as 3 subtypes based on cause7: (1) classical SS, also known as idiopathic SS, can be preceded by an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract infection or vaccination, or can be pregnancy associated2; (2) drug-induced SS usually follows use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, or other causative drugs including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, quinolones, oral contraceptives, furosemide, hydralazine, diazepam, clozapine, abacavir, imatinib, bortezomib, azathioprine, and celecoxib2,3,8; and (3) malignancy-associated SS can occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome and generally is associated with hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor.1,9

In our patient, the observed clinical and histological findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SS,2,10 specifically tender erythematous plaques of sudden onset, fast response to systemic corticosteroid therapy, a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and leukocytosis greater than 8000/µL with more than 70% neutrophils. He also exhibited targetoid lesions, which have been reported in 7% to 12% of SS patients.10,11

The predominant cells involved in the dermis of SS lesions are mature neutrophils; however, eosinophils have been observed in small numbers within dermal infiltrates in skin lesions of patients with either classical SS or drug-induced dermatosis.2 In 2 studies of cases of SS (N=73 and N=31), eosinophils were reported in 35% and 41% of skin biopsies, respectively.4,5 Nevertheless, cases with dense eosinophilic infiltrates are rare. Furthermore, Masuda et al12 reported a case of eosinophil-rich SS in a 29-year-old woman after treatment of an upper respiratory tract infection with an antibiotic, and Soon et al13 described an eosinophil-rich case of SS in the setting of new-onset enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Our patient was considered to have classical SS because he had an episode of an upper respiratory tract infection 1 week prior to onset of clinical manifestations. The histologic finding of numerous eosinophils in our case was unusual for idiopathic SS. This finding might suggest a drug hypersensitivity reaction, but the lack of any change in the patient’s long-term medication list and the lack of any other episodes made a diagnosis of drug-induced SS less likely in our patient.

Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is a rare cutaneous condition in which nodules, pruritic papules, and vesicles arise in patients with a hematologic malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma,13 in which a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and numerous eosinophils are observed. Malignancy was ruled out in our patient because of the lack of characteristic abnormalities in blood testing, the fast response to corticosteroid therapy, and the lack of recurrence posttreatment or additional systemic concerns.

The typical pathology findings of SS consist of mature neutrophils found in the dermis without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Eosinophil-rich infiltration, however rare, has been reported in SS. This report highlights a case of classical SS with a particularly dense eosinophilic infiltrate, which could be mistaken for other eosinophilic dermatoses. Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of marked eosinophilic infiltration in all subtypes of this disorder.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is an uncommon inflammatory skin disorder characterized by sudden onset of fever, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and tender erythematous papules or plaques or both. Skin biopsy usually reveals extensive infiltration of neutrophils into the epidermis and dermis.1-3 Although rare, cases of eosinophil-rich SS have been reported in patients with drug-induced and malignancy-associated SS.4,5 We report a case of a patient with classical SS with dermal eosinophilic infiltration.

An 80-year-old Hispanic man presented with abrupt onset of a rash on the posterior scalp, left ear, back, and hands of 5 days’ duration. The lesions were painful and had progressed to the point of impairing hand grip. The patient’s medical history included a reported common cold the week prior, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, for which he took metoprolol, simvastatin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. He denied oral lesions and medication changes. He was afebrile and did not experience dietary changes, weight loss, or fatigue. He recently returned from travel to the Dominican Republic.

Physical examination revealed tender, well demarcated, pink to violaceous, pseudovesicular papules and plaques on the palms and dorsal hands (Figure 1), the posterior scalp, left ear, proximal left arm, and back. Pink, juicy, targetoid papules were also found on the scalp, back, and left arm. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Laboratory test results revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,500/µL [reference range, 3800-10,800/µL]), absolute neutrophil count (8073/µL [reference range, 1500–7800/µL]), and eosinophil count (610/µL [reference range, 15–500/µL]). These results indicated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and mild eosinophilia. The patient also was anemic (hemoglobin, 11.5 g/dL [reference range, 13.2–17.1 g/dL]; hematocrit, 35.1% [reference range, 38.5%–50%]). Urine testing revealed altered renal function (serum creatinine, 2.42 mg/dL [reference range, 0.7–1.1 mg/dL]; blood urea nitrogen, 34 mg/dL [reference range, 7–25 mg/dL]; glomerular filtration rate, 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2]), suggesting stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Urinalysis showed mild hematuria and proteinuria.

Histopathology of biopsies taken from plaques on the left arm and lower back revealed a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with numerous scattered eosinophils in the dermis. Some neutrophils were intact; others were fragmented without evidence of vasculitis. A subtle subepidermal edema also was noted (Figure 2). A diagnosis of SS was made.

Initial treatment included prednisone (40 mg daily, tapered by 5 mg every 3 days) and erythromycin (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days because of suspected Mycoplasma infection. The rash resolved in 1 week. No recurrence was noted during 4 months of follow-up. The white blood cell count returned to within reference range (8400/µL), ruling out the possibility of a smoldering myeloid process.

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis was first described in a case series of 8 women by Sweet6 in 1964. Patients typically present first with fever, which can precede cutaneous symptoms for days or weeks. Skin lesions generally are asymmetric and located on the face, neck, and upper extremities. Lesions can be described as painful, purple to red papules, plaques, or nodules. Sweet syndrome can present as 3 subtypes based on cause7: (1) classical SS, also known as idiopathic SS, can be preceded by an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract infection or vaccination, or can be pregnancy associated2; (2) drug-induced SS usually follows use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, or other causative drugs including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, quinolones, oral contraceptives, furosemide, hydralazine, diazepam, clozapine, abacavir, imatinib, bortezomib, azathioprine, and celecoxib2,3,8; and (3) malignancy-associated SS can occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome and generally is associated with hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor.1,9

In our patient, the observed clinical and histological findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SS,2,10 specifically tender erythematous plaques of sudden onset, fast response to systemic corticosteroid therapy, a dermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and leukocytosis greater than 8000/µL with more than 70% neutrophils. He also exhibited targetoid lesions, which have been reported in 7% to 12% of SS patients.10,11

The predominant cells involved in the dermis of SS lesions are mature neutrophils; however, eosinophils have been observed in small numbers within dermal infiltrates in skin lesions of patients with either classical SS or drug-induced dermatosis.2 In 2 studies of cases of SS (N=73 and N=31), eosinophils were reported in 35% and 41% of skin biopsies, respectively.4,5 Nevertheless, cases with dense eosinophilic infiltrates are rare. Furthermore, Masuda et al12 reported a case of eosinophil-rich SS in a 29-year-old woman after treatment of an upper respiratory tract infection with an antibiotic, and Soon et al13 described an eosinophil-rich case of SS in the setting of new-onset enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Our patient was considered to have classical SS because he had an episode of an upper respiratory tract infection 1 week prior to onset of clinical manifestations. The histologic finding of numerous eosinophils in our case was unusual for idiopathic SS. This finding might suggest a drug hypersensitivity reaction, but the lack of any change in the patient’s long-term medication list and the lack of any other episodes made a diagnosis of drug-induced SS less likely in our patient.

Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is a rare cutaneous condition in which nodules, pruritic papules, and vesicles arise in patients with a hematologic malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma,13 in which a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and numerous eosinophils are observed. Malignancy was ruled out in our patient because of the lack of characteristic abnormalities in blood testing, the fast response to corticosteroid therapy, and the lack of recurrence posttreatment or additional systemic concerns.

The typical pathology findings of SS consist of mature neutrophils found in the dermis without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Eosinophil-rich infiltration, however rare, has been reported in SS. This report highlights a case of classical SS with a particularly dense eosinophilic infiltrate, which could be mistaken for other eosinophilic dermatoses. Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of marked eosinophilic infiltration in all subtypes of this disorder.

- Herbert-Cohen D, Jour G, Saul T. Sweet’s syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:e95-e97.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378.

- Rochael MC, Pantaleão L, Vilar EA, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: study of 73 cases, emphasizing histopathological findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:702-707.

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Polimeni G, Cardillo R, Garaffo E, et al. Allopurinol-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:329-332.

- Paydas S. Sweet’s syndrome: a revisit for hematologists and oncologists. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;86:85-95.

- Amouri M, Masmoudi A, Ammar M, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: a retrospective study of 90 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1033-1039.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Masuda T, Abe Y, Arata J, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) associated with extreme infiltration of eosinophils. J Dermatol. 1994;21:341-346.

- Soon CW, Kirsch IR, Connolly AJ, et al. Eosinophil-rich acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in a patient with enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, type 1. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:704-708.

- Herbert-Cohen D, Jour G, Saul T. Sweet’s syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:e95-e97.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378.

- Rochael MC, Pantaleão L, Vilar EA, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: study of 73 cases, emphasizing histopathological findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:702-707.

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

- Polimeni G, Cardillo R, Garaffo E, et al. Allopurinol-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29:329-332.

- Paydas S. Sweet’s syndrome: a revisit for hematologists and oncologists. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;86:85-95.

- Amouri M, Masmoudi A, Ammar M, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: a retrospective study of 90 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1033-1039.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Masuda T, Abe Y, Arata J, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) associated with extreme infiltration of eosinophils. J Dermatol. 1994;21:341-346.

- Soon CW, Kirsch IR, Connolly AJ, et al. Eosinophil-rich acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis in a patient with enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, type 1. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:704-708.

Practice Points

- This report highlights a case of classical Sweet syndrome (SS) with a particularly dense eosinophilic infiltrate, which could be mistaken for other eosinophilic dermatoses.

- Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of marked eosinophilic infiltration in all subtypes of SS.

Can you identify these numerous papules in the groin area?

Condylomata acuminata

Condylomata acuminata (CA), or anogenital warts, are the cutaneous manifestation of infection by human papillomavirus (HPV). The virus is transmitted primarily via sexual contact with infected skin or mucosa, although it also may result from nonsexual contact or vertical transmission during vaginal delivery.1 More than 200 types of HPV have been identified; however, genotypes 6 and 11 are most commonly implicated in the development of CA and are associated with a low risk for oncogenesis. Nevertheless, CA pose a tremendous economic and psychological burden on the health care system and those affected, respectively, representing the most common sexually transmitted viral disease in the United States.2

Clinical presentation

CA present as discrete or clustered smooth, papillomatous, sessile, exophytic papules or plaques, often lacking the thick, horny scale seen in common warts, and they may be broad based or pedunculated.2 The anogenital region is affected, including the external genitalia, perineum, perianal area, and adjacent skin such as the mons pubis and inguinal folds. Extension into the urethra or vaginal, cervical, and anal canals is possible, although rarely beyond the dentate line.2,3 Lesions typically are asymptomatic but may be extensive or disfiguring, often noticed by patients upon self-inspection and leading to significant distress. Symptoms such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or discharge may develop in traumatized or secondarily infected lesions.1,3

Diagnosis

Although CA can be diagnosed clinically, biopsy facilitates definitive diagnosis in less clear-cut cases.1,3 Histologically, CA are characterized by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis, with the presence of koilocytes in the epidermis.2

Treatment

Treatment of CA is challenging, as there are currently no antiviral therapies available to cure the condition. Treatment options include destructive, immunomodulatory, and antiproliferative therapies, either alone or in combination. There is no first-line therapy indicated for CA, and treatment selection is dependent on multiple patient-specific factors, including the size, number, and anatomic location of the lesions, as well as ease of treatment and adverse effects.2

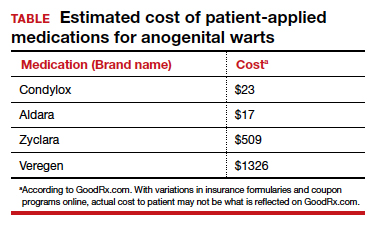

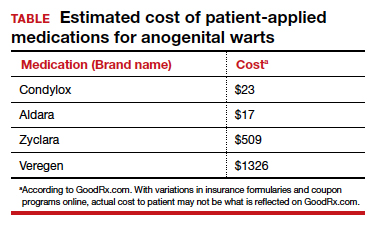

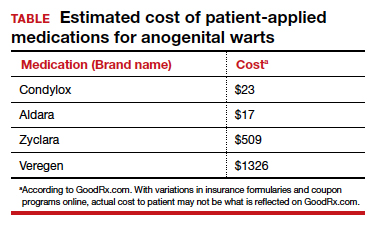

Topical therapies. For external CA, there are several treatments that may be applied by patients themselves, including topical podophyllotoxin, imiquimod, and sinecatechins (TABLE).1 Podophyllotoxin (brand name Condylox) is an antiproliferative agent available as a 0.15% cream or 0.5% solution.1,2 It should be applied twice daily for 3 consecutive days per week for up to 4 weeks. Podophyllotoxin is contraindicated in pregnancy and may cause local irritation.2

Imiquimod (brand names Aldara and Zyclara) is an immunomodulatory, available as a 5% and 3.75% cream. For external genital warts, the cream should be applied 3 times per week for up to 16 weeks; for perianal warts it should be applied daily for up to 8 weeks. Adverse effects of imiquimod include local irritation and systemic flu-like symptoms and are prominent with the 3.75% formulation, reducing adherence.1,2,4

In-office treatment options include cryotherapy, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), intralesional immunotherapy, laser therapy, phototherapy, and surgical options.2 Liquid nitrogen is cost-effective, efficacious, and safe for use in pregnancy; it is used in 2 to 3 freeze/thaw cycles per cryotherapy session to induce cellular damage.1,2 Its disadvantages include adverse effects, such as blistering, ulceration, dyspigmentation, and scarring. In addition, subclinical lesions in adjacent skin are not addressed during treatment.2

TCA is a caustic agent applied in the office once weekly or every 2 to 3 weeks for a maximum of 3 to 4 months, with similar benefits to cryotherapy in terms of ease of application and safety in pregnancy. There is the risk of blistering and ulceration in treated lesions as well as in inadvertently treated adjacent skin.1

Intralesional immunotherapy with Candida antigen (brand name Candin) is used in 3 sessions 4 to 6 weeks apart and is safe, with minimal adverse effects.2

Laser therapy treatment options include carbon dioxide laser therapy and ND:YAG laser. Their use is limited, however, by availability and cost.1,2

CA may be removed surgically via shave excision, scissor excision, curettage, and electrosurgery. These procedures can be painful, however, requiring local anesthesia and having a prolonged healing course.1,2

CA recurrence

CA unfortunately has a high rate of recurrence despite treatment, and patients require extensive counseling. Patients should be screened for other sexually transmitted infections and advised to notify their sexual partners. If followed properly, safe sexual practices, including condom use and limiting sexual partners, may prevent further transmission.1 The quadrivalent HPV vaccine (effective for the prevention of infection with HPV genotypes 6, 11, 16, and 18 in unexposed individuals) is ineffective in treating patients with pre-existing CA but can protect against the acquisition of other HPV genotypes included in the vaccine.1,5

Arriving at the diagnosis

Acrochordons are a common skin finding in the groin, but the onset is more gradual and the individual lesions tend to be more pedunculated. Molluscum is also on the differential and can affect the genitalia. Molluscum lesions have a characteristic central dimple or dell, which is absent in CA.

CASE Treatment course

The patient was treated with successive sessions of cryotherapy in combination with a course of topical imiquimod followed by several injections with Candida antigen, with persistence of some lesions as well as recurrence.

- Steben M, Garland SM. Genital warts. Best Prac Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:1063-1073.

- Fathi R, Tsoukas MM. Genital warts and other HPV infections: established and novel therapies. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:299-306.

- Lynde C, Vender R, Bourcier M, et al. Clinical features of external genital warts. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17 (suppl 2):S55-60.

- Scheinfeld N. Update on the treatment of genital warts. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18559.

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56:1-24.

Condylomata acuminata

Condylomata acuminata (CA), or anogenital warts, are the cutaneous manifestation of infection by human papillomavirus (HPV). The virus is transmitted primarily via sexual contact with infected skin or mucosa, although it also may result from nonsexual contact or vertical transmission during vaginal delivery.1 More than 200 types of HPV have been identified; however, genotypes 6 and 11 are most commonly implicated in the development of CA and are associated with a low risk for oncogenesis. Nevertheless, CA pose a tremendous economic and psychological burden on the health care system and those affected, respectively, representing the most common sexually transmitted viral disease in the United States.2

Clinical presentation

CA present as discrete or clustered smooth, papillomatous, sessile, exophytic papules or plaques, often lacking the thick, horny scale seen in common warts, and they may be broad based or pedunculated.2 The anogenital region is affected, including the external genitalia, perineum, perianal area, and adjacent skin such as the mons pubis and inguinal folds. Extension into the urethra or vaginal, cervical, and anal canals is possible, although rarely beyond the dentate line.2,3 Lesions typically are asymptomatic but may be extensive or disfiguring, often noticed by patients upon self-inspection and leading to significant distress. Symptoms such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or discharge may develop in traumatized or secondarily infected lesions.1,3

Diagnosis

Although CA can be diagnosed clinically, biopsy facilitates definitive diagnosis in less clear-cut cases.1,3 Histologically, CA are characterized by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis, with the presence of koilocytes in the epidermis.2

Treatment

Treatment of CA is challenging, as there are currently no antiviral therapies available to cure the condition. Treatment options include destructive, immunomodulatory, and antiproliferative therapies, either alone or in combination. There is no first-line therapy indicated for CA, and treatment selection is dependent on multiple patient-specific factors, including the size, number, and anatomic location of the lesions, as well as ease of treatment and adverse effects.2

Topical therapies. For external CA, there are several treatments that may be applied by patients themselves, including topical podophyllotoxin, imiquimod, and sinecatechins (TABLE).1 Podophyllotoxin (brand name Condylox) is an antiproliferative agent available as a 0.15% cream or 0.5% solution.1,2 It should be applied twice daily for 3 consecutive days per week for up to 4 weeks. Podophyllotoxin is contraindicated in pregnancy and may cause local irritation.2

Imiquimod (brand names Aldara and Zyclara) is an immunomodulatory, available as a 5% and 3.75% cream. For external genital warts, the cream should be applied 3 times per week for up to 16 weeks; for perianal warts it should be applied daily for up to 8 weeks. Adverse effects of imiquimod include local irritation and systemic flu-like symptoms and are prominent with the 3.75% formulation, reducing adherence.1,2,4

In-office treatment options include cryotherapy, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), intralesional immunotherapy, laser therapy, phototherapy, and surgical options.2 Liquid nitrogen is cost-effective, efficacious, and safe for use in pregnancy; it is used in 2 to 3 freeze/thaw cycles per cryotherapy session to induce cellular damage.1,2 Its disadvantages include adverse effects, such as blistering, ulceration, dyspigmentation, and scarring. In addition, subclinical lesions in adjacent skin are not addressed during treatment.2

TCA is a caustic agent applied in the office once weekly or every 2 to 3 weeks for a maximum of 3 to 4 months, with similar benefits to cryotherapy in terms of ease of application and safety in pregnancy. There is the risk of blistering and ulceration in treated lesions as well as in inadvertently treated adjacent skin.1

Intralesional immunotherapy with Candida antigen (brand name Candin) is used in 3 sessions 4 to 6 weeks apart and is safe, with minimal adverse effects.2

Laser therapy treatment options include carbon dioxide laser therapy and ND:YAG laser. Their use is limited, however, by availability and cost.1,2

CA may be removed surgically via shave excision, scissor excision, curettage, and electrosurgery. These procedures can be painful, however, requiring local anesthesia and having a prolonged healing course.1,2

CA recurrence

CA unfortunately has a high rate of recurrence despite treatment, and patients require extensive counseling. Patients should be screened for other sexually transmitted infections and advised to notify their sexual partners. If followed properly, safe sexual practices, including condom use and limiting sexual partners, may prevent further transmission.1 The quadrivalent HPV vaccine (effective for the prevention of infection with HPV genotypes 6, 11, 16, and 18 in unexposed individuals) is ineffective in treating patients with pre-existing CA but can protect against the acquisition of other HPV genotypes included in the vaccine.1,5

Arriving at the diagnosis

Acrochordons are a common skin finding in the groin, but the onset is more gradual and the individual lesions tend to be more pedunculated. Molluscum is also on the differential and can affect the genitalia. Molluscum lesions have a characteristic central dimple or dell, which is absent in CA.

CASE Treatment course

The patient was treated with successive sessions of cryotherapy in combination with a course of topical imiquimod followed by several injections with Candida antigen, with persistence of some lesions as well as recurrence.

Condylomata acuminata

Condylomata acuminata (CA), or anogenital warts, are the cutaneous manifestation of infection by human papillomavirus (HPV). The virus is transmitted primarily via sexual contact with infected skin or mucosa, although it also may result from nonsexual contact or vertical transmission during vaginal delivery.1 More than 200 types of HPV have been identified; however, genotypes 6 and 11 are most commonly implicated in the development of CA and are associated with a low risk for oncogenesis. Nevertheless, CA pose a tremendous economic and psychological burden on the health care system and those affected, respectively, representing the most common sexually transmitted viral disease in the United States.2

Clinical presentation

CA present as discrete or clustered smooth, papillomatous, sessile, exophytic papules or plaques, often lacking the thick, horny scale seen in common warts, and they may be broad based or pedunculated.2 The anogenital region is affected, including the external genitalia, perineum, perianal area, and adjacent skin such as the mons pubis and inguinal folds. Extension into the urethra or vaginal, cervical, and anal canals is possible, although rarely beyond the dentate line.2,3 Lesions typically are asymptomatic but may be extensive or disfiguring, often noticed by patients upon self-inspection and leading to significant distress. Symptoms such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or discharge may develop in traumatized or secondarily infected lesions.1,3

Diagnosis

Although CA can be diagnosed clinically, biopsy facilitates definitive diagnosis in less clear-cut cases.1,3 Histologically, CA are characterized by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis, with the presence of koilocytes in the epidermis.2

Treatment

Treatment of CA is challenging, as there are currently no antiviral therapies available to cure the condition. Treatment options include destructive, immunomodulatory, and antiproliferative therapies, either alone or in combination. There is no first-line therapy indicated for CA, and treatment selection is dependent on multiple patient-specific factors, including the size, number, and anatomic location of the lesions, as well as ease of treatment and adverse effects.2

Topical therapies. For external CA, there are several treatments that may be applied by patients themselves, including topical podophyllotoxin, imiquimod, and sinecatechins (TABLE).1 Podophyllotoxin (brand name Condylox) is an antiproliferative agent available as a 0.15% cream or 0.5% solution.1,2 It should be applied twice daily for 3 consecutive days per week for up to 4 weeks. Podophyllotoxin is contraindicated in pregnancy and may cause local irritation.2

Imiquimod (brand names Aldara and Zyclara) is an immunomodulatory, available as a 5% and 3.75% cream. For external genital warts, the cream should be applied 3 times per week for up to 16 weeks; for perianal warts it should be applied daily for up to 8 weeks. Adverse effects of imiquimod include local irritation and systemic flu-like symptoms and are prominent with the 3.75% formulation, reducing adherence.1,2,4

In-office treatment options include cryotherapy, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), intralesional immunotherapy, laser therapy, phototherapy, and surgical options.2 Liquid nitrogen is cost-effective, efficacious, and safe for use in pregnancy; it is used in 2 to 3 freeze/thaw cycles per cryotherapy session to induce cellular damage.1,2 Its disadvantages include adverse effects, such as blistering, ulceration, dyspigmentation, and scarring. In addition, subclinical lesions in adjacent skin are not addressed during treatment.2

TCA is a caustic agent applied in the office once weekly or every 2 to 3 weeks for a maximum of 3 to 4 months, with similar benefits to cryotherapy in terms of ease of application and safety in pregnancy. There is the risk of blistering and ulceration in treated lesions as well as in inadvertently treated adjacent skin.1

Intralesional immunotherapy with Candida antigen (brand name Candin) is used in 3 sessions 4 to 6 weeks apart and is safe, with minimal adverse effects.2

Laser therapy treatment options include carbon dioxide laser therapy and ND:YAG laser. Their use is limited, however, by availability and cost.1,2

CA may be removed surgically via shave excision, scissor excision, curettage, and electrosurgery. These procedures can be painful, however, requiring local anesthesia and having a prolonged healing course.1,2

CA recurrence

CA unfortunately has a high rate of recurrence despite treatment, and patients require extensive counseling. Patients should be screened for other sexually transmitted infections and advised to notify their sexual partners. If followed properly, safe sexual practices, including condom use and limiting sexual partners, may prevent further transmission.1 The quadrivalent HPV vaccine (effective for the prevention of infection with HPV genotypes 6, 11, 16, and 18 in unexposed individuals) is ineffective in treating patients with pre-existing CA but can protect against the acquisition of other HPV genotypes included in the vaccine.1,5

Arriving at the diagnosis

Acrochordons are a common skin finding in the groin, but the onset is more gradual and the individual lesions tend to be more pedunculated. Molluscum is also on the differential and can affect the genitalia. Molluscum lesions have a characteristic central dimple or dell, which is absent in CA.

CASE Treatment course

The patient was treated with successive sessions of cryotherapy in combination with a course of topical imiquimod followed by several injections with Candida antigen, with persistence of some lesions as well as recurrence.

- Steben M, Garland SM. Genital warts. Best Prac Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:1063-1073.

- Fathi R, Tsoukas MM. Genital warts and other HPV infections: established and novel therapies. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:299-306.

- Lynde C, Vender R, Bourcier M, et al. Clinical features of external genital warts. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17 (suppl 2):S55-60.

- Scheinfeld N. Update on the treatment of genital warts. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18559.

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56:1-24.

- Steben M, Garland SM. Genital warts. Best Prac Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:1063-1073.

- Fathi R, Tsoukas MM. Genital warts and other HPV infections: established and novel therapies. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:299-306.

- Lynde C, Vender R, Bourcier M, et al. Clinical features of external genital warts. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17 (suppl 2):S55-60.

- Scheinfeld N. Update on the treatment of genital warts. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18559.

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56:1-24.

CASE Skin tags on the groin

A 47-year-old woman with no personal history of skin cancer presents to a dermatologist for annual skin surveillance examination. She notes multiple “pink skin tags” on the groin, present for 4 months. She says they are asymptomatic and have not been treated previously. She states that she is in a long-term monogamous relationship. Physical examination reveals multiple smooth, flat-topped, pedunculated pink papules on the bilateral upper inner thighs. Shave biopsy of a lesion on the right upper medial thigh is performed to aid in diagnosis (FIGURE 1).