User login

Maximizing Throughput and Improving Patient Flow

According to data from the American Hospital Association (1), in 1985, the United States had 5732 operational community hospitals; by 2002, the latest year for which figures are available, the number had decreased to 4927, a loss of approximately 14% (1). In that same timeframe, these hospitals lost approximately 18% of their beds, dropping from just over 1 million to 820,653 beds. This reduction in bed capacity has been accompanied by hospital cost-cutting efforts, staff downsizing, and elimination of services. Many explanations for these trends have been suggested, including changes in Medicare reimbursement and the growth of managed care organizations (MCOs).

However, as the current baby boom generation ages, rising inpatient demands are presenting hospitals with significant challenges. According to a 2001 report from Solucient (2), who maintains the nation’s largest health care database, the senior population—individuals age 65 and older—are projected to experience an 85% growth rate over the next two decades. Since this age group utilizes inpatient services 4.5 times more than younger populations, the number of admissions and beds to accommodate those cases will soar. By the year 2027, hospitals can anticipate a 46% rise in demand for acute inpatient beds as admissions escalate by approximately 13 million cases. Currently, the nation’s healthcare facilities admit 31 million cases; this number will jump to more than 44 million, representing a 41% growth from present admissions figures. For hospitals that maintain an 80% census rate, an additional 238,000 beds will be needed to meet demands (1).

Adding to this increase in demand and pressure on bed capacity, hospitals must address the requirements of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) passed by the US Congress in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act (COBRA). The law’s initial intent was to ensure patient access to emergency medical care and to prevent the practice of patient dumping, in which uninsured patients were transferred, solely for financial reasons, from private to public hospitals without consideration of their medical condition or stability for the transfer (3). EMTALA mandates that hospitals rank the severity of patients. Thus, tertiary referral centers are required to admit the sickest patients first. This directive presents a significant challenge to many healthcare facilities. High census rates prohibit the admission of elective surgical cases, which, although profitable, are considered second tier. Routine medical cases or complicated emergency surgical cases have the potential to adversely affect the institution’s financial performance.

In addition to the challenge of increased bed demands and EMTALA, hospitals also cite an increasingly smaller number of on-site community physicians. Longstanding trends from inpatient to outpatient care have prompted many community physicians to concentrate their efforts on serving the needs of office-based patients, limiting their accessibility to hospital cases.

To address these pressures, hospitals must execute innovative strategies that deliver efficient throughput and enhance revenue, while still preserving high-quality services. Since 1996, hospital medicine programs have demonstrated a positive impact on the healthcare facility’s ability to increase overall productivity and profitability and still maintain high quality Patients today present to the doctor sicker than in the past and require more careful and frequent outpatient care. Since hospitalists operate solely on an inpatient basis, their availability to efficiently admit and manage hospitalized patients enables delivery of quality care that expedites appropriate treatment and shortens length of stay.

Two Roles of the Hospitalist

According to the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), “Hospitalists are physicians whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.” Coined by Drs. Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman in 1996 (4), the term implies an additional point of emphasis. Part of a new paradigm in clinical care, the hospitalist enhances the processes of care surrounding patients and adopts an attitude of accountability for that care. In practice, hospitalists play two key roles.

Primarily, the hospitalist is a practicing clinician — managing throughput on a case-by-case, patient-by-patient basis. In addition, a hospitalist performs a non-clinical role as an “inpatient expert,” taking the lead in creating system changes and communicating those changes to other hospital personnel as well as to community physicians. As an inpatient expert, hospitalists are often asked to lead organization-wide throughput initiatives to identify and implement strategies to facilitate patient flow and efficiency. As dedicated members of multi-disciplinary in-house teams, the hospitalist is in a prime position to foster change and improve systems.

Throughput as Continuum of Care

As suggested by Heffner (5), the process of admission, hospitalization, and discharge resembles a “bell-shaped curve.” To achieve effective throughput, hospitals must expedite patient care and also maintain careful oversight throughout a patient’s entire hospital stay. The hospitalist, as an integral part of a multidisciplinary team, coordinates care to promote a positive outcome and shorten length of stay. Drawing on strong leadership qualities, as well as on intimate knowledge of hospital procedures, layout design and infrastructure, and available community resources, the hospitalist plays a pivotal role in creating efficient throughput from admission to discharge.

Emergency Department

At the front end of the bell-shaped curve, the hospitalist may be engaged by emergency department (ED) physicians to assist in ensuring smooth patient flow and, more important, identifies the “intensity of service” needed. Through the use of clinical criteria, such as lnterQual, the hospitalist, together with the ED physician, may be asked to quantitatively rate the patient’s illness for degree of severity.

Timely patient evaluation helps prevent a backlog of ED cases and enables more patients to be seen. Immediate attention to and initiation of appropriate therapy guarantees a better outcome while minimizing the potential risk for complications, which could possibly lead to longer inpatient stays.

Inpatient Unit

Once a patient has been admitted to an inpatient unit, the hospitalist, together with a multidisciplinary team, facilitates care and determines the inpatient services that will optimize patient recovery through strong interdepartmental communications. Working together with admissions, medical records, nursing, laboratory and diagnostic services, information technology and other pertinent departments, the hospitalist maintains a pulse on all activity surrounding the patient and his care.

Judicious inpatient consultations and treatment decisions result in timely changes in therapy, potentially reducing the length of stay. The frequency with which the hospitalist sees the patient allows him to monitor any changes in condition and reduce possible decompensation, a practice known as vertical continuity (6). Such careful attention may reduce inpatient length of stay significantly. When aggressive management is mandated, the presence of the hospitalist enables initiation of effective therapy and results in quicker discharge and a reduction in potential readmission (7).

Surgery

The surgeon and hospitalist are ideally suited to work together in managing a surgical patient. The hospitalist focuses on the peri-operative management of medical issues and risk reduction, which allows the surgeon to concentrate more on surgical indications and the surgery itself. The hospitalist’s role in the management of a surgical patient enables vertical continuity when the surgeon may be occupied in the operating room with another patient as documented by Huddleston’s Hospitalist Orthopedic Team (HOT) approach (8).

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

In many hospitals, particularly those that do not have intensivists, hospitalists are able to provide quality care to patients. Even in hospitals where intensivists manage ICU patients, hospitalists work together with the intensivist to ensure smoother transition into and out of the unit.

Discharge

Timing is a critical issue with regard to discharge. Since the hospitalist operates solely in-house and in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, he is able to round early in the day to discharge patients by mid- or late-morning, freeing a bed for a new patient. In some cases, the hospitalist, in anticipation of early discharge, may begin pre-planning the day prior to discharge, which further expedites the process. Early discharge applies to the ICU, step-down areas and general inpatient care areas, as well as to full discharge from the healthcare facility. Moving a patient from one of these areas enables other patients to fill those empty beds thus optimizing throughput.

Having managed the patient throughout his hospital stay, the hospitalist — again working together with a multidisciplinary team —can facilitate arrangements to send the patient home or to a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility or alternative housing situation upon discharge, as well as coordinating post-discharge care, whether it be arranging for a visiting nursing or social services or communicating with the primary care physician regarding follow-up appointments. If additional outpatient care is prescribed, the hospitalist will work with the discharge planning staff to contact various community agencies to arrange services best suited to the patient’s needs. Efficient discharge makes possible the admission of other, more critically ill patients, potentially enhancing the hospital’s revenue stream.

Stakeholder Analysis

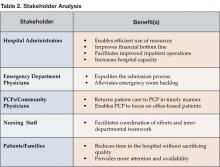

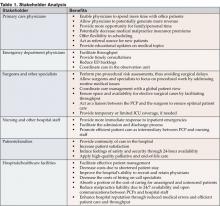

Five specific stakeholders need to be examined to document the value-added by hospitalists. Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated numerous returns—physical, social, psychological and financial—to stakeholders involved in the hospital process. With regard to throughput, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the stakeholders listed in Table 1.

Study Results

A dozen studies have been conducted that document the impact of hospital medicine programs on cost and clinical outcomes. Of these trials, nine found a significant decrease in the average length of stay (15%) as well as reductions in cost (9). Two other studies, one from an academic medical center and the other from a community teaching hospital, demonstrate similar reductions during a 2-year follow-up period. At the Western Penn Hospital, a 54% reduction in readmissions was reported with a 12% decrease in hospital costs, while the average LOS was 17% shorter. Additionally, an unpublished study from the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center revealed a consistent 10-15% decline in cost and length of stay between hospitalists and non-hospitalist teaching faculty. More important, those differences remained stable through 6 years of follow-up. In general, hospitals with hospitalist programs realized a 5-39% decrease in costs and a shortened average LOS of 7-25% (6).

According to Robert M. Wachter, author of the 2002 study, “If the average U.S. hospitalist cares for 600 inpatients each year and generates a 10% savings over the average medical inpatient cost of $8,000, the nation’s 4500 hospitalists save approximately $2.2 billion per year while potentially improving quality” (6).

In a study conducted by Douglas Gregory, Walter Baigelman, and Ira B. Wilson, hospitalists at Tufts-New England Medical Center in Boston, MA were found to substantially improve throughput with high baseline occupancy levels. Compared with a control group, the hospitalist group reduced LOS from 3.45 days to 2.19 days (p<.001). Additionally, the total cost of hospital admission decreased from $2,332 to $1,775 (p<.001) when hospitalists were involved. According to the study authors, improved throughput generated an incremental 266 patients per year with a related incremental hospital profitability of $1.3 million with the use of hospitalists (7).

Conclusion

As hospital administrators attempt to address the issue of expeditiously admitting, treating and discharging patients in these days of restricted budgets and increased demand, hospitalist programs are poised as an invaluable factor in the throughput process.

Dr. Cawley can be contacted at pcawley@ushosp.com.

References

- Hospital Statistics: the comprehensive reference source for analysis and comparison of hospital trends. Published annually by Health Forum, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association.

- National and local impact of long-term demographic change on inpatient acute care. 2001. Solucient, LLC.

- Zibulewsky J. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): what it is and what it means for physicians. Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) Proceedings. 2001;14:339-46.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

- Heffner JE. Executive medical director, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Personal interview. June 24, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:905-18.

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:28-38.

- Wachter RM. The evolution of the hospitalist model in the United States. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:687-706.

According to data from the American Hospital Association (1), in 1985, the United States had 5732 operational community hospitals; by 2002, the latest year for which figures are available, the number had decreased to 4927, a loss of approximately 14% (1). In that same timeframe, these hospitals lost approximately 18% of their beds, dropping from just over 1 million to 820,653 beds. This reduction in bed capacity has been accompanied by hospital cost-cutting efforts, staff downsizing, and elimination of services. Many explanations for these trends have been suggested, including changes in Medicare reimbursement and the growth of managed care organizations (MCOs).

However, as the current baby boom generation ages, rising inpatient demands are presenting hospitals with significant challenges. According to a 2001 report from Solucient (2), who maintains the nation’s largest health care database, the senior population—individuals age 65 and older—are projected to experience an 85% growth rate over the next two decades. Since this age group utilizes inpatient services 4.5 times more than younger populations, the number of admissions and beds to accommodate those cases will soar. By the year 2027, hospitals can anticipate a 46% rise in demand for acute inpatient beds as admissions escalate by approximately 13 million cases. Currently, the nation’s healthcare facilities admit 31 million cases; this number will jump to more than 44 million, representing a 41% growth from present admissions figures. For hospitals that maintain an 80% census rate, an additional 238,000 beds will be needed to meet demands (1).

Adding to this increase in demand and pressure on bed capacity, hospitals must address the requirements of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) passed by the US Congress in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act (COBRA). The law’s initial intent was to ensure patient access to emergency medical care and to prevent the practice of patient dumping, in which uninsured patients were transferred, solely for financial reasons, from private to public hospitals without consideration of their medical condition or stability for the transfer (3). EMTALA mandates that hospitals rank the severity of patients. Thus, tertiary referral centers are required to admit the sickest patients first. This directive presents a significant challenge to many healthcare facilities. High census rates prohibit the admission of elective surgical cases, which, although profitable, are considered second tier. Routine medical cases or complicated emergency surgical cases have the potential to adversely affect the institution’s financial performance.

In addition to the challenge of increased bed demands and EMTALA, hospitals also cite an increasingly smaller number of on-site community physicians. Longstanding trends from inpatient to outpatient care have prompted many community physicians to concentrate their efforts on serving the needs of office-based patients, limiting their accessibility to hospital cases.

To address these pressures, hospitals must execute innovative strategies that deliver efficient throughput and enhance revenue, while still preserving high-quality services. Since 1996, hospital medicine programs have demonstrated a positive impact on the healthcare facility’s ability to increase overall productivity and profitability and still maintain high quality Patients today present to the doctor sicker than in the past and require more careful and frequent outpatient care. Since hospitalists operate solely on an inpatient basis, their availability to efficiently admit and manage hospitalized patients enables delivery of quality care that expedites appropriate treatment and shortens length of stay.

Two Roles of the Hospitalist

According to the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), “Hospitalists are physicians whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.” Coined by Drs. Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman in 1996 (4), the term implies an additional point of emphasis. Part of a new paradigm in clinical care, the hospitalist enhances the processes of care surrounding patients and adopts an attitude of accountability for that care. In practice, hospitalists play two key roles.

Primarily, the hospitalist is a practicing clinician — managing throughput on a case-by-case, patient-by-patient basis. In addition, a hospitalist performs a non-clinical role as an “inpatient expert,” taking the lead in creating system changes and communicating those changes to other hospital personnel as well as to community physicians. As an inpatient expert, hospitalists are often asked to lead organization-wide throughput initiatives to identify and implement strategies to facilitate patient flow and efficiency. As dedicated members of multi-disciplinary in-house teams, the hospitalist is in a prime position to foster change and improve systems.

Throughput as Continuum of Care

As suggested by Heffner (5), the process of admission, hospitalization, and discharge resembles a “bell-shaped curve.” To achieve effective throughput, hospitals must expedite patient care and also maintain careful oversight throughout a patient’s entire hospital stay. The hospitalist, as an integral part of a multidisciplinary team, coordinates care to promote a positive outcome and shorten length of stay. Drawing on strong leadership qualities, as well as on intimate knowledge of hospital procedures, layout design and infrastructure, and available community resources, the hospitalist plays a pivotal role in creating efficient throughput from admission to discharge.

Emergency Department

At the front end of the bell-shaped curve, the hospitalist may be engaged by emergency department (ED) physicians to assist in ensuring smooth patient flow and, more important, identifies the “intensity of service” needed. Through the use of clinical criteria, such as lnterQual, the hospitalist, together with the ED physician, may be asked to quantitatively rate the patient’s illness for degree of severity.

Timely patient evaluation helps prevent a backlog of ED cases and enables more patients to be seen. Immediate attention to and initiation of appropriate therapy guarantees a better outcome while minimizing the potential risk for complications, which could possibly lead to longer inpatient stays.

Inpatient Unit

Once a patient has been admitted to an inpatient unit, the hospitalist, together with a multidisciplinary team, facilitates care and determines the inpatient services that will optimize patient recovery through strong interdepartmental communications. Working together with admissions, medical records, nursing, laboratory and diagnostic services, information technology and other pertinent departments, the hospitalist maintains a pulse on all activity surrounding the patient and his care.

Judicious inpatient consultations and treatment decisions result in timely changes in therapy, potentially reducing the length of stay. The frequency with which the hospitalist sees the patient allows him to monitor any changes in condition and reduce possible decompensation, a practice known as vertical continuity (6). Such careful attention may reduce inpatient length of stay significantly. When aggressive management is mandated, the presence of the hospitalist enables initiation of effective therapy and results in quicker discharge and a reduction in potential readmission (7).

Surgery

The surgeon and hospitalist are ideally suited to work together in managing a surgical patient. The hospitalist focuses on the peri-operative management of medical issues and risk reduction, which allows the surgeon to concentrate more on surgical indications and the surgery itself. The hospitalist’s role in the management of a surgical patient enables vertical continuity when the surgeon may be occupied in the operating room with another patient as documented by Huddleston’s Hospitalist Orthopedic Team (HOT) approach (8).

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

In many hospitals, particularly those that do not have intensivists, hospitalists are able to provide quality care to patients. Even in hospitals where intensivists manage ICU patients, hospitalists work together with the intensivist to ensure smoother transition into and out of the unit.

Discharge

Timing is a critical issue with regard to discharge. Since the hospitalist operates solely in-house and in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, he is able to round early in the day to discharge patients by mid- or late-morning, freeing a bed for a new patient. In some cases, the hospitalist, in anticipation of early discharge, may begin pre-planning the day prior to discharge, which further expedites the process. Early discharge applies to the ICU, step-down areas and general inpatient care areas, as well as to full discharge from the healthcare facility. Moving a patient from one of these areas enables other patients to fill those empty beds thus optimizing throughput.

Having managed the patient throughout his hospital stay, the hospitalist — again working together with a multidisciplinary team —can facilitate arrangements to send the patient home or to a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility or alternative housing situation upon discharge, as well as coordinating post-discharge care, whether it be arranging for a visiting nursing or social services or communicating with the primary care physician regarding follow-up appointments. If additional outpatient care is prescribed, the hospitalist will work with the discharge planning staff to contact various community agencies to arrange services best suited to the patient’s needs. Efficient discharge makes possible the admission of other, more critically ill patients, potentially enhancing the hospital’s revenue stream.

Stakeholder Analysis

Five specific stakeholders need to be examined to document the value-added by hospitalists. Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated numerous returns—physical, social, psychological and financial—to stakeholders involved in the hospital process. With regard to throughput, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the stakeholders listed in Table 1.

Study Results

A dozen studies have been conducted that document the impact of hospital medicine programs on cost and clinical outcomes. Of these trials, nine found a significant decrease in the average length of stay (15%) as well as reductions in cost (9). Two other studies, one from an academic medical center and the other from a community teaching hospital, demonstrate similar reductions during a 2-year follow-up period. At the Western Penn Hospital, a 54% reduction in readmissions was reported with a 12% decrease in hospital costs, while the average LOS was 17% shorter. Additionally, an unpublished study from the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center revealed a consistent 10-15% decline in cost and length of stay between hospitalists and non-hospitalist teaching faculty. More important, those differences remained stable through 6 years of follow-up. In general, hospitals with hospitalist programs realized a 5-39% decrease in costs and a shortened average LOS of 7-25% (6).

According to Robert M. Wachter, author of the 2002 study, “If the average U.S. hospitalist cares for 600 inpatients each year and generates a 10% savings over the average medical inpatient cost of $8,000, the nation’s 4500 hospitalists save approximately $2.2 billion per year while potentially improving quality” (6).

In a study conducted by Douglas Gregory, Walter Baigelman, and Ira B. Wilson, hospitalists at Tufts-New England Medical Center in Boston, MA were found to substantially improve throughput with high baseline occupancy levels. Compared with a control group, the hospitalist group reduced LOS from 3.45 days to 2.19 days (p<.001). Additionally, the total cost of hospital admission decreased from $2,332 to $1,775 (p<.001) when hospitalists were involved. According to the study authors, improved throughput generated an incremental 266 patients per year with a related incremental hospital profitability of $1.3 million with the use of hospitalists (7).

Conclusion

As hospital administrators attempt to address the issue of expeditiously admitting, treating and discharging patients in these days of restricted budgets and increased demand, hospitalist programs are poised as an invaluable factor in the throughput process.

Dr. Cawley can be contacted at pcawley@ushosp.com.

References

- Hospital Statistics: the comprehensive reference source for analysis and comparison of hospital trends. Published annually by Health Forum, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association.

- National and local impact of long-term demographic change on inpatient acute care. 2001. Solucient, LLC.

- Zibulewsky J. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): what it is and what it means for physicians. Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) Proceedings. 2001;14:339-46.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

- Heffner JE. Executive medical director, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Personal interview. June 24, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:905-18.

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:28-38.

- Wachter RM. The evolution of the hospitalist model in the United States. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:687-706.

According to data from the American Hospital Association (1), in 1985, the United States had 5732 operational community hospitals; by 2002, the latest year for which figures are available, the number had decreased to 4927, a loss of approximately 14% (1). In that same timeframe, these hospitals lost approximately 18% of their beds, dropping from just over 1 million to 820,653 beds. This reduction in bed capacity has been accompanied by hospital cost-cutting efforts, staff downsizing, and elimination of services. Many explanations for these trends have been suggested, including changes in Medicare reimbursement and the growth of managed care organizations (MCOs).

However, as the current baby boom generation ages, rising inpatient demands are presenting hospitals with significant challenges. According to a 2001 report from Solucient (2), who maintains the nation’s largest health care database, the senior population—individuals age 65 and older—are projected to experience an 85% growth rate over the next two decades. Since this age group utilizes inpatient services 4.5 times more than younger populations, the number of admissions and beds to accommodate those cases will soar. By the year 2027, hospitals can anticipate a 46% rise in demand for acute inpatient beds as admissions escalate by approximately 13 million cases. Currently, the nation’s healthcare facilities admit 31 million cases; this number will jump to more than 44 million, representing a 41% growth from present admissions figures. For hospitals that maintain an 80% census rate, an additional 238,000 beds will be needed to meet demands (1).

Adding to this increase in demand and pressure on bed capacity, hospitals must address the requirements of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) passed by the US Congress in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act (COBRA). The law’s initial intent was to ensure patient access to emergency medical care and to prevent the practice of patient dumping, in which uninsured patients were transferred, solely for financial reasons, from private to public hospitals without consideration of their medical condition or stability for the transfer (3). EMTALA mandates that hospitals rank the severity of patients. Thus, tertiary referral centers are required to admit the sickest patients first. This directive presents a significant challenge to many healthcare facilities. High census rates prohibit the admission of elective surgical cases, which, although profitable, are considered second tier. Routine medical cases or complicated emergency surgical cases have the potential to adversely affect the institution’s financial performance.

In addition to the challenge of increased bed demands and EMTALA, hospitals also cite an increasingly smaller number of on-site community physicians. Longstanding trends from inpatient to outpatient care have prompted many community physicians to concentrate their efforts on serving the needs of office-based patients, limiting their accessibility to hospital cases.

To address these pressures, hospitals must execute innovative strategies that deliver efficient throughput and enhance revenue, while still preserving high-quality services. Since 1996, hospital medicine programs have demonstrated a positive impact on the healthcare facility’s ability to increase overall productivity and profitability and still maintain high quality Patients today present to the doctor sicker than in the past and require more careful and frequent outpatient care. Since hospitalists operate solely on an inpatient basis, their availability to efficiently admit and manage hospitalized patients enables delivery of quality care that expedites appropriate treatment and shortens length of stay.

Two Roles of the Hospitalist

According to the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), “Hospitalists are physicians whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.” Coined by Drs. Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman in 1996 (4), the term implies an additional point of emphasis. Part of a new paradigm in clinical care, the hospitalist enhances the processes of care surrounding patients and adopts an attitude of accountability for that care. In practice, hospitalists play two key roles.

Primarily, the hospitalist is a practicing clinician — managing throughput on a case-by-case, patient-by-patient basis. In addition, a hospitalist performs a non-clinical role as an “inpatient expert,” taking the lead in creating system changes and communicating those changes to other hospital personnel as well as to community physicians. As an inpatient expert, hospitalists are often asked to lead organization-wide throughput initiatives to identify and implement strategies to facilitate patient flow and efficiency. As dedicated members of multi-disciplinary in-house teams, the hospitalist is in a prime position to foster change and improve systems.

Throughput as Continuum of Care

As suggested by Heffner (5), the process of admission, hospitalization, and discharge resembles a “bell-shaped curve.” To achieve effective throughput, hospitals must expedite patient care and also maintain careful oversight throughout a patient’s entire hospital stay. The hospitalist, as an integral part of a multidisciplinary team, coordinates care to promote a positive outcome and shorten length of stay. Drawing on strong leadership qualities, as well as on intimate knowledge of hospital procedures, layout design and infrastructure, and available community resources, the hospitalist plays a pivotal role in creating efficient throughput from admission to discharge.

Emergency Department

At the front end of the bell-shaped curve, the hospitalist may be engaged by emergency department (ED) physicians to assist in ensuring smooth patient flow and, more important, identifies the “intensity of service” needed. Through the use of clinical criteria, such as lnterQual, the hospitalist, together with the ED physician, may be asked to quantitatively rate the patient’s illness for degree of severity.

Timely patient evaluation helps prevent a backlog of ED cases and enables more patients to be seen. Immediate attention to and initiation of appropriate therapy guarantees a better outcome while minimizing the potential risk for complications, which could possibly lead to longer inpatient stays.

Inpatient Unit

Once a patient has been admitted to an inpatient unit, the hospitalist, together with a multidisciplinary team, facilitates care and determines the inpatient services that will optimize patient recovery through strong interdepartmental communications. Working together with admissions, medical records, nursing, laboratory and diagnostic services, information technology and other pertinent departments, the hospitalist maintains a pulse on all activity surrounding the patient and his care.

Judicious inpatient consultations and treatment decisions result in timely changes in therapy, potentially reducing the length of stay. The frequency with which the hospitalist sees the patient allows him to monitor any changes in condition and reduce possible decompensation, a practice known as vertical continuity (6). Such careful attention may reduce inpatient length of stay significantly. When aggressive management is mandated, the presence of the hospitalist enables initiation of effective therapy and results in quicker discharge and a reduction in potential readmission (7).

Surgery

The surgeon and hospitalist are ideally suited to work together in managing a surgical patient. The hospitalist focuses on the peri-operative management of medical issues and risk reduction, which allows the surgeon to concentrate more on surgical indications and the surgery itself. The hospitalist’s role in the management of a surgical patient enables vertical continuity when the surgeon may be occupied in the operating room with another patient as documented by Huddleston’s Hospitalist Orthopedic Team (HOT) approach (8).

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

In many hospitals, particularly those that do not have intensivists, hospitalists are able to provide quality care to patients. Even in hospitals where intensivists manage ICU patients, hospitalists work together with the intensivist to ensure smoother transition into and out of the unit.

Discharge

Timing is a critical issue with regard to discharge. Since the hospitalist operates solely in-house and in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, he is able to round early in the day to discharge patients by mid- or late-morning, freeing a bed for a new patient. In some cases, the hospitalist, in anticipation of early discharge, may begin pre-planning the day prior to discharge, which further expedites the process. Early discharge applies to the ICU, step-down areas and general inpatient care areas, as well as to full discharge from the healthcare facility. Moving a patient from one of these areas enables other patients to fill those empty beds thus optimizing throughput.

Having managed the patient throughout his hospital stay, the hospitalist — again working together with a multidisciplinary team —can facilitate arrangements to send the patient home or to a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility or alternative housing situation upon discharge, as well as coordinating post-discharge care, whether it be arranging for a visiting nursing or social services or communicating with the primary care physician regarding follow-up appointments. If additional outpatient care is prescribed, the hospitalist will work with the discharge planning staff to contact various community agencies to arrange services best suited to the patient’s needs. Efficient discharge makes possible the admission of other, more critically ill patients, potentially enhancing the hospital’s revenue stream.

Stakeholder Analysis

Five specific stakeholders need to be examined to document the value-added by hospitalists. Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated numerous returns—physical, social, psychological and financial—to stakeholders involved in the hospital process. With regard to throughput, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the stakeholders listed in Table 1.

Study Results

A dozen studies have been conducted that document the impact of hospital medicine programs on cost and clinical outcomes. Of these trials, nine found a significant decrease in the average length of stay (15%) as well as reductions in cost (9). Two other studies, one from an academic medical center and the other from a community teaching hospital, demonstrate similar reductions during a 2-year follow-up period. At the Western Penn Hospital, a 54% reduction in readmissions was reported with a 12% decrease in hospital costs, while the average LOS was 17% shorter. Additionally, an unpublished study from the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center revealed a consistent 10-15% decline in cost and length of stay between hospitalists and non-hospitalist teaching faculty. More important, those differences remained stable through 6 years of follow-up. In general, hospitals with hospitalist programs realized a 5-39% decrease in costs and a shortened average LOS of 7-25% (6).

According to Robert M. Wachter, author of the 2002 study, “If the average U.S. hospitalist cares for 600 inpatients each year and generates a 10% savings over the average medical inpatient cost of $8,000, the nation’s 4500 hospitalists save approximately $2.2 billion per year while potentially improving quality” (6).

In a study conducted by Douglas Gregory, Walter Baigelman, and Ira B. Wilson, hospitalists at Tufts-New England Medical Center in Boston, MA were found to substantially improve throughput with high baseline occupancy levels. Compared with a control group, the hospitalist group reduced LOS from 3.45 days to 2.19 days (p<.001). Additionally, the total cost of hospital admission decreased from $2,332 to $1,775 (p<.001) when hospitalists were involved. According to the study authors, improved throughput generated an incremental 266 patients per year with a related incremental hospital profitability of $1.3 million with the use of hospitalists (7).

Conclusion

As hospital administrators attempt to address the issue of expeditiously admitting, treating and discharging patients in these days of restricted budgets and increased demand, hospitalist programs are poised as an invaluable factor in the throughput process.

Dr. Cawley can be contacted at pcawley@ushosp.com.

References

- Hospital Statistics: the comprehensive reference source for analysis and comparison of hospital trends. Published annually by Health Forum, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association.

- National and local impact of long-term demographic change on inpatient acute care. 2001. Solucient, LLC.

- Zibulewsky J. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): what it is and what it means for physicians. Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) Proceedings. 2001;14:339-46.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

- Heffner JE. Executive medical director, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Personal interview. June 24, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:905-18.

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:28-38.

- Wachter RM. The evolution of the hospitalist model in the United States. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:687-706.

Improving Resource Utilization

Today’s hospitals must address a variety of challenges stemming from the expectation to provide more services and better quality with fewer financial, material, and human resources. According to the annual survey conducted by the American Hospital Association (AHA) in 2003, total expenses for all U.S. community hospitals were more than $450 billion. In managing these expenditures, hospitals face the following pressures:

- Cost increases in medical supplies and pharmaceuticals.

- Record shortages of nurses, pharmacists, and technicians.

- A growing uncompensated patient pool.

- Annual potential reductions in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Rising bad debt resulting from greater patient responsibility for the cost of care.

- The diversion of more profitable cases to specialty and freestanding ambulatory care facilities and surgery centers.

- Soaring costs associated with adequately serving high-risk conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS.

- Discounted reimbursement rates with insurers.

- Increasing pressure to commit financial resources to clinical information technology.

- The need to fund infrastructure improvements and physical plant renovations as well as expansions to address increasing demand (1).

To overcome these challenges, hospitals must find innovative ways to balance revenues and expenses, fund necessary capital investments, and satisfy the public’s demand for quality, safety, and accessibility.

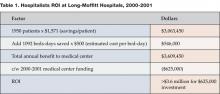

Hospitalist Programs: A Good Investment

One solution to the above-mentioned situations is a hospitalist program, which, in its short history, has already had a profound impact on inpatient care. Robert M. Wachter, MD, associate chair in the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and medical service chief at Moffitt-Long Hospitals, coined the term Hospitalist in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1996 (2). At the 2002 annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), Wachter presented findings from a study conducted at his institution. The results demonstrate a significant return on investment (ROI) of 5.8:1 when a hospitalist program is utilized (See Table 1 for details) (3).

How do hospitalists reduce length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay? William David Rifkin, MD, associate director of the Yale Primary Care Residency Program, offers three basic reasons why hospitalist programs contribute to effective and efficient use of resources. Since hospitalists are physically onsite, they are better able to react to condition changes and requests for consultations in a timely manner, he asserts. Also, being familiar with the hospital’s systems of care, the hospitalist knows who to call and how to utilize the services of social workers and other contingency staff when arranging for post-discharge care. Third, Rifkin indicates that inpatients today are sicker than they were in past years, a fact well known and understood by hospitalists. “There is an increased level of acuity,” he says. “Hospitalists are used to seeing these kinds of patients. They are more comfortable taking care of these patients and will see more of them with any given diagnosis” (4).

In one of his studies, Rifkin noted a reduction in LOS for inpatients with a pneumonia diagnosis. “The hospitalist had switched the patient from IV (intravenous) to oral antibiotics,” he says. Reacting quickly to indications that the patient was ready for a change in treatment modality facilitated an earlier discharge (5).

L. Craig Miller, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Baptist Health Care, reports that his hospital saved $2.56 million in 2 years as a direct result of its inpatient management program (6). Although attention to technical and clinical details is important, Miller emphasizes the critical role the human factor plays, specifically the impact of teamwork, on achieving resource utilization savings.

“Hospitalists work as a team, collaborating with physicians and ED doctors,” he says. This cooperative spirit enables the efficient use of manpower in patient care. Miller adds that at Baptist, as is the case at most hospitals, the medical complexity of patients dictates a need for cooperation in order to successfully treat illness. The presence of hospitalists facilitates the team effort, causing a positive trickle down effect regarding LOS, readmission and mortality rates, he affirms. “The hospitalist provides focused leadership to utilization resource management,” says Miller (7).

In the role of inpatient leader, the hospitalist also facilitates ED throughput, which results in another area of cost savings for the hospital. Paola Coppola, MD, ED director at Brookhaven Memorial Hospital Medical Center, says, “From an ER perspective, a call to the hospitalist replaces multiple calls to specialists. In general, hospitalists feel much more comfortable treating a wide array of conditions including infectious disease, pneumonias, strokes, and chest pain without the intervention of specialists in that field. Hence, hospital consumption of resources decreases, which in turn lowers length of stay.” He echoes Rifkin’s thoughts on quick response time. “Hospitalists provide an immediately available service, thus saving ER physicians valuable time. This ensures faster turnover, better throughput, makes more ER beds available, and services more patients, eventually helping the hospital’s bottom line,” says Coppola (8).

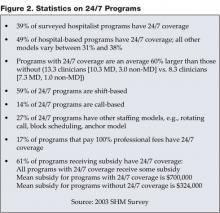

In addition to teamwork, 24/7 availability is vital to the wise utilization of resources, according to Anthony Shallash, MD, vice president of medical affairs at Brookhaven. “The fact of 24/7 presence allows rapid responses to patient condition and problems. Continuous and close monitoring of patients allows them to be upgraded or downgraded as needed,” he says. “As such, LOS is decreased and quite favorable as compared to peer practitioners for similar disease severity. Resources consumed and tests ordered also show a favorable trend” (9).

A recently published study (10) by researchers at Dartmouth Medical School documents the variation in the volume and cost of services that academic medical centers use in treating patients. Hospitals were categorized as low- and high-intensity, with significant differences in cost per case. For example, the high-intensity hospitals spent up to 47% more on care for acute myocardial infarction. In an interview in Today’s Hospitalist (11), the lead author, Elliott S. Fisher, MD, professor of medicine and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, described the importance of coordination in achieving efficient care. Fisher says, “I think there’s a real opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of patients in both high- and low- intensity hospitals. Having ten doctors involved in a given patient’s care may not be a good thing, unless someone [i.e., the hospitalist] is doing a really good job of coordinating that care.”

Hospitalists focus only on inpatient medicine. They are familiar with managing the most common medical diagnoses, such as community acquired pneumonia, diabetes. and congestive heart failure. Hospitalist programs often develop uniform and consistent ways of treating these patients. Cogent Healthcare, a national hospitalist management company has implemented the “Cogent Care Guides,” best practice guidelines for high-volume hospital diagnoses. Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP and Cogent’s chief medical officer, says “The Cogent Care Guides ensure best practices are implemented at critical points in the patient’s care… decreasing the variability of care that results in inefficiencies.” Greeno added, “The care guidelines [also] support the timely notification of the primary care physician of nine critical landmark events related to patient status that can affect outcomes” (12).

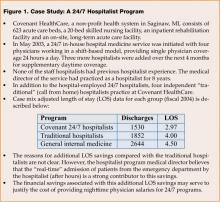

Stacy Goldsholl, Director of the Covenant HealthCare Hospital Medicine Program in Saginaw, MI, suggests other ways that hospitalists can generate utilization savings for their hospitals. “Hospitalists often eliminate unnecessary admissions and shift work-ups to the ambulatory setting. For example, I recently arranged an outpatient colonoscopy for a pneumonia patient with a stable hemoglobin and heme positive stool. Because of my experience treating patients with pneumonia, I was able to determine that the circumstances did not require an inpatient stay.” In addition, Dr. Goldsholl has found that the hospitalists in her program are quite effective in classifying “observation” patients, eliminating reimbursement conflicts with Medicare, Medicaid, and other insurers.

Finally, because they are always in the hospital rather than sharing time between the office and hospital, hospitalists can improve inpatient continuity of care, resulting in lower costs and better outcomes. Adrienne Bennett, MD, chief of the hospital medicine service at Newton-Wellesley Hospital near Boston, examined cases managed by hospitalists and non-hospitalist community physicians, comparing the number of “handoffs” of responsibility that occur among attending physicians. Community physicians share inpatient responsibility in their practices and sometimes their partners round on their patients. Every time another physician assumes responsibility for a patient, there is the potential for a loss of information and a discontinuity of care. At Newton-Wellesley Hospital, the hospitalists work a schedule of 14 days on, followed by 7 days off. “We found that hospitalists averaged less than half the number of handoffs as the community physicians,” says Bennett. “This may be one of the reasons that hospitalists have better case mix adjusted utilization performance.”

Stakeholder Analysis

Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated that hospitalists provide value to a wide range of stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. With regard to resource utilization savings, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the listed stakeholders (Table 2).

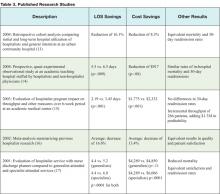

Published Research Results

Dozens of studies demonstrate the positive effects hospitalist programs have on resource utilization. Observational, retrospective, and prospective data analyses have been conducted at community-based hospitals as well as at academic medical institutions. Findings consistently indicate that hospitalist programs result in resource savings for patients, physicians. and hospital medicine. A range of studies shown in Table 3 represent the most recent efforts at tracking hospitalist programs and their effects on resource utilization.

Conclusion

According to the AHA’s 2003 survey of healthcare trends, the fiscal health of the nation’s hospitals will most likely remain fragile and variable in the coming years. The survey cites declining operating margins, a continued decrease in reimbursement, labor shortages, and rising insurance and pharmaceutical costs, as well as the need to invest in technology and facility maintenance and upkeep as key factors. However, hospitalists have proven time and again in clinical studies that they can bring value to the operation of a healthcare facility. With reduced lengths of stay, decreased overall hospital costs, and equivalent — if not superior — quality, hospitalists can contribute significantly to a hospital’s healthy bottom line.

Dr. Syed can be contacted at syed.saeed@CogentHealthcare.com.

References

- ACP Research Center, Environmental Assessment: Trends in hospital financing. 2003. www.aha.org.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7

- Wachter RM. Presentation, Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual meeting 2002. 4. Rifkin WD. Telephone interview December 15, 2004.

- Rifkin WD, Conner D, Silver A, Eichom A. Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community-based primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:1053-8.

- “Hospitalists save $2.5 million and decrease LOS.” Healthcare Benchmarks and Quality Improvement, May 2004.

- Miller LC. Telephone intewiew, November 16, 2004.

- Coppola P. Email interview, December 15,2004.

- Shallash A. Email interview, December17, 2004.

- Healthaffairs.org, “Use of Medicare claims data to monitor provider-specific performance among patients with severe chronic illness.” 10.1377/hlthaff.var.5. Posting date: October 7, 2004.

- Why less really can be more when it comes to teaching hospitals. Today’s Hospitalist. 2004 December.

- Greeno R. Chief medical officer, Cogent Healthcare, Irvine, California. Telephone interview. December 16, 2004.

- Everett GD, Anton MP Jackson BK, Swigert C, Uddin N. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay associated with general internists and hospitalist physicians at a community hospital. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:626-30.

- Kaboli PJ, Barnett MJ, Rosenthal GE. Associations with reduced length of stay and costs on an academic hospitalist service. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:561-8.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Services Research. 2003:38(3):905-18; discussion 919-22.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287:487-94.

- Palmer HC, Armistead NS, Elnicki DM, et al. The effect of a hospitalist service with nurse discharge planner on patient care in an academic teaching hospital. Am J Med. 2001;111:627-32.

Today’s hospitals must address a variety of challenges stemming from the expectation to provide more services and better quality with fewer financial, material, and human resources. According to the annual survey conducted by the American Hospital Association (AHA) in 2003, total expenses for all U.S. community hospitals were more than $450 billion. In managing these expenditures, hospitals face the following pressures:

- Cost increases in medical supplies and pharmaceuticals.

- Record shortages of nurses, pharmacists, and technicians.

- A growing uncompensated patient pool.

- Annual potential reductions in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Rising bad debt resulting from greater patient responsibility for the cost of care.

- The diversion of more profitable cases to specialty and freestanding ambulatory care facilities and surgery centers.

- Soaring costs associated with adequately serving high-risk conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS.

- Discounted reimbursement rates with insurers.

- Increasing pressure to commit financial resources to clinical information technology.

- The need to fund infrastructure improvements and physical plant renovations as well as expansions to address increasing demand (1).

To overcome these challenges, hospitals must find innovative ways to balance revenues and expenses, fund necessary capital investments, and satisfy the public’s demand for quality, safety, and accessibility.

Hospitalist Programs: A Good Investment

One solution to the above-mentioned situations is a hospitalist program, which, in its short history, has already had a profound impact on inpatient care. Robert M. Wachter, MD, associate chair in the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and medical service chief at Moffitt-Long Hospitals, coined the term Hospitalist in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1996 (2). At the 2002 annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), Wachter presented findings from a study conducted at his institution. The results demonstrate a significant return on investment (ROI) of 5.8:1 when a hospitalist program is utilized (See Table 1 for details) (3).

How do hospitalists reduce length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay? William David Rifkin, MD, associate director of the Yale Primary Care Residency Program, offers three basic reasons why hospitalist programs contribute to effective and efficient use of resources. Since hospitalists are physically onsite, they are better able to react to condition changes and requests for consultations in a timely manner, he asserts. Also, being familiar with the hospital’s systems of care, the hospitalist knows who to call and how to utilize the services of social workers and other contingency staff when arranging for post-discharge care. Third, Rifkin indicates that inpatients today are sicker than they were in past years, a fact well known and understood by hospitalists. “There is an increased level of acuity,” he says. “Hospitalists are used to seeing these kinds of patients. They are more comfortable taking care of these patients and will see more of them with any given diagnosis” (4).

In one of his studies, Rifkin noted a reduction in LOS for inpatients with a pneumonia diagnosis. “The hospitalist had switched the patient from IV (intravenous) to oral antibiotics,” he says. Reacting quickly to indications that the patient was ready for a change in treatment modality facilitated an earlier discharge (5).

L. Craig Miller, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Baptist Health Care, reports that his hospital saved $2.56 million in 2 years as a direct result of its inpatient management program (6). Although attention to technical and clinical details is important, Miller emphasizes the critical role the human factor plays, specifically the impact of teamwork, on achieving resource utilization savings.

“Hospitalists work as a team, collaborating with physicians and ED doctors,” he says. This cooperative spirit enables the efficient use of manpower in patient care. Miller adds that at Baptist, as is the case at most hospitals, the medical complexity of patients dictates a need for cooperation in order to successfully treat illness. The presence of hospitalists facilitates the team effort, causing a positive trickle down effect regarding LOS, readmission and mortality rates, he affirms. “The hospitalist provides focused leadership to utilization resource management,” says Miller (7).

In the role of inpatient leader, the hospitalist also facilitates ED throughput, which results in another area of cost savings for the hospital. Paola Coppola, MD, ED director at Brookhaven Memorial Hospital Medical Center, says, “From an ER perspective, a call to the hospitalist replaces multiple calls to specialists. In general, hospitalists feel much more comfortable treating a wide array of conditions including infectious disease, pneumonias, strokes, and chest pain without the intervention of specialists in that field. Hence, hospital consumption of resources decreases, which in turn lowers length of stay.” He echoes Rifkin’s thoughts on quick response time. “Hospitalists provide an immediately available service, thus saving ER physicians valuable time. This ensures faster turnover, better throughput, makes more ER beds available, and services more patients, eventually helping the hospital’s bottom line,” says Coppola (8).

In addition to teamwork, 24/7 availability is vital to the wise utilization of resources, according to Anthony Shallash, MD, vice president of medical affairs at Brookhaven. “The fact of 24/7 presence allows rapid responses to patient condition and problems. Continuous and close monitoring of patients allows them to be upgraded or downgraded as needed,” he says. “As such, LOS is decreased and quite favorable as compared to peer practitioners for similar disease severity. Resources consumed and tests ordered also show a favorable trend” (9).

A recently published study (10) by researchers at Dartmouth Medical School documents the variation in the volume and cost of services that academic medical centers use in treating patients. Hospitals were categorized as low- and high-intensity, with significant differences in cost per case. For example, the high-intensity hospitals spent up to 47% more on care for acute myocardial infarction. In an interview in Today’s Hospitalist (11), the lead author, Elliott S. Fisher, MD, professor of medicine and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, described the importance of coordination in achieving efficient care. Fisher says, “I think there’s a real opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of patients in both high- and low- intensity hospitals. Having ten doctors involved in a given patient’s care may not be a good thing, unless someone [i.e., the hospitalist] is doing a really good job of coordinating that care.”

Hospitalists focus only on inpatient medicine. They are familiar with managing the most common medical diagnoses, such as community acquired pneumonia, diabetes. and congestive heart failure. Hospitalist programs often develop uniform and consistent ways of treating these patients. Cogent Healthcare, a national hospitalist management company has implemented the “Cogent Care Guides,” best practice guidelines for high-volume hospital diagnoses. Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP and Cogent’s chief medical officer, says “The Cogent Care Guides ensure best practices are implemented at critical points in the patient’s care… decreasing the variability of care that results in inefficiencies.” Greeno added, “The care guidelines [also] support the timely notification of the primary care physician of nine critical landmark events related to patient status that can affect outcomes” (12).

Stacy Goldsholl, Director of the Covenant HealthCare Hospital Medicine Program in Saginaw, MI, suggests other ways that hospitalists can generate utilization savings for their hospitals. “Hospitalists often eliminate unnecessary admissions and shift work-ups to the ambulatory setting. For example, I recently arranged an outpatient colonoscopy for a pneumonia patient with a stable hemoglobin and heme positive stool. Because of my experience treating patients with pneumonia, I was able to determine that the circumstances did not require an inpatient stay.” In addition, Dr. Goldsholl has found that the hospitalists in her program are quite effective in classifying “observation” patients, eliminating reimbursement conflicts with Medicare, Medicaid, and other insurers.

Finally, because they are always in the hospital rather than sharing time between the office and hospital, hospitalists can improve inpatient continuity of care, resulting in lower costs and better outcomes. Adrienne Bennett, MD, chief of the hospital medicine service at Newton-Wellesley Hospital near Boston, examined cases managed by hospitalists and non-hospitalist community physicians, comparing the number of “handoffs” of responsibility that occur among attending physicians. Community physicians share inpatient responsibility in their practices and sometimes their partners round on their patients. Every time another physician assumes responsibility for a patient, there is the potential for a loss of information and a discontinuity of care. At Newton-Wellesley Hospital, the hospitalists work a schedule of 14 days on, followed by 7 days off. “We found that hospitalists averaged less than half the number of handoffs as the community physicians,” says Bennett. “This may be one of the reasons that hospitalists have better case mix adjusted utilization performance.”

Stakeholder Analysis

Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated that hospitalists provide value to a wide range of stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. With regard to resource utilization savings, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the listed stakeholders (Table 2).

Published Research Results

Dozens of studies demonstrate the positive effects hospitalist programs have on resource utilization. Observational, retrospective, and prospective data analyses have been conducted at community-based hospitals as well as at academic medical institutions. Findings consistently indicate that hospitalist programs result in resource savings for patients, physicians. and hospital medicine. A range of studies shown in Table 3 represent the most recent efforts at tracking hospitalist programs and their effects on resource utilization.

Conclusion

According to the AHA’s 2003 survey of healthcare trends, the fiscal health of the nation’s hospitals will most likely remain fragile and variable in the coming years. The survey cites declining operating margins, a continued decrease in reimbursement, labor shortages, and rising insurance and pharmaceutical costs, as well as the need to invest in technology and facility maintenance and upkeep as key factors. However, hospitalists have proven time and again in clinical studies that they can bring value to the operation of a healthcare facility. With reduced lengths of stay, decreased overall hospital costs, and equivalent — if not superior — quality, hospitalists can contribute significantly to a hospital’s healthy bottom line.

Dr. Syed can be contacted at syed.saeed@CogentHealthcare.com.

References

- ACP Research Center, Environmental Assessment: Trends in hospital financing. 2003. www.aha.org.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514-7

- Wachter RM. Presentation, Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) annual meeting 2002. 4. Rifkin WD. Telephone interview December 15, 2004.

- Rifkin WD, Conner D, Silver A, Eichom A. Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community-based primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:1053-8.

- “Hospitalists save $2.5 million and decrease LOS.” Healthcare Benchmarks and Quality Improvement, May 2004.

- Miller LC. Telephone intewiew, November 16, 2004.

- Coppola P. Email interview, December 15,2004.

- Shallash A. Email interview, December17, 2004.

- Healthaffairs.org, “Use of Medicare claims data to monitor provider-specific performance among patients with severe chronic illness.” 10.1377/hlthaff.var.5. Posting date: October 7, 2004.

- Why less really can be more when it comes to teaching hospitals. Today’s Hospitalist. 2004 December.

- Greeno R. Chief medical officer, Cogent Healthcare, Irvine, California. Telephone interview. December 16, 2004.

- Everett GD, Anton MP Jackson BK, Swigert C, Uddin N. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay associated with general internists and hospitalist physicians at a community hospital. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:626-30.

- Kaboli PJ, Barnett MJ, Rosenthal GE. Associations with reduced length of stay and costs on an academic hospitalist service. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:561-8.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Services Research. 2003:38(3):905-18; discussion 919-22.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287:487-94.

- Palmer HC, Armistead NS, Elnicki DM, et al. The effect of a hospitalist service with nurse discharge planner on patient care in an academic teaching hospital. Am J Med. 2001;111:627-32.

Today’s hospitals must address a variety of challenges stemming from the expectation to provide more services and better quality with fewer financial, material, and human resources. According to the annual survey conducted by the American Hospital Association (AHA) in 2003, total expenses for all U.S. community hospitals were more than $450 billion. In managing these expenditures, hospitals face the following pressures:

- Cost increases in medical supplies and pharmaceuticals.

- Record shortages of nurses, pharmacists, and technicians.

- A growing uncompensated patient pool.

- Annual potential reductions in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Rising bad debt resulting from greater patient responsibility for the cost of care.

- The diversion of more profitable cases to specialty and freestanding ambulatory care facilities and surgery centers.

- Soaring costs associated with adequately serving high-risk conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS.

- Discounted reimbursement rates with insurers.

- Increasing pressure to commit financial resources to clinical information technology.

- The need to fund infrastructure improvements and physical plant renovations as well as expansions to address increasing demand (1).

To overcome these challenges, hospitals must find innovative ways to balance revenues and expenses, fund necessary capital investments, and satisfy the public’s demand for quality, safety, and accessibility.

Hospitalist Programs: A Good Investment

One solution to the above-mentioned situations is a hospitalist program, which, in its short history, has already had a profound impact on inpatient care. Robert M. Wachter, MD, associate chair in the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and medical service chief at Moffitt-Long Hospitals, coined the term Hospitalist in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1996 (2). At the 2002 annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), Wachter presented findings from a study conducted at his institution. The results demonstrate a significant return on investment (ROI) of 5.8:1 when a hospitalist program is utilized (See Table 1 for details) (3).

How do hospitalists reduce length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay? William David Rifkin, MD, associate director of the Yale Primary Care Residency Program, offers three basic reasons why hospitalist programs contribute to effective and efficient use of resources. Since hospitalists are physically onsite, they are better able to react to condition changes and requests for consultations in a timely manner, he asserts. Also, being familiar with the hospital’s systems of care, the hospitalist knows who to call and how to utilize the services of social workers and other contingency staff when arranging for post-discharge care. Third, Rifkin indicates that inpatients today are sicker than they were in past years, a fact well known and understood by hospitalists. “There is an increased level of acuity,” he says. “Hospitalists are used to seeing these kinds of patients. They are more comfortable taking care of these patients and will see more of them with any given diagnosis” (4).

In one of his studies, Rifkin noted a reduction in LOS for inpatients with a pneumonia diagnosis. “The hospitalist had switched the patient from IV (intravenous) to oral antibiotics,” he says. Reacting quickly to indications that the patient was ready for a change in treatment modality facilitated an earlier discharge (5).

L. Craig Miller, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Baptist Health Care, reports that his hospital saved $2.56 million in 2 years as a direct result of its inpatient management program (6). Although attention to technical and clinical details is important, Miller emphasizes the critical role the human factor plays, specifically the impact of teamwork, on achieving resource utilization savings.

“Hospitalists work as a team, collaborating with physicians and ED doctors,” he says. This cooperative spirit enables the efficient use of manpower in patient care. Miller adds that at Baptist, as is the case at most hospitals, the medical complexity of patients dictates a need for cooperation in order to successfully treat illness. The presence of hospitalists facilitates the team effort, causing a positive trickle down effect regarding LOS, readmission and mortality rates, he affirms. “The hospitalist provides focused leadership to utilization resource management,” says Miller (7).

In the role of inpatient leader, the hospitalist also facilitates ED throughput, which results in another area of cost savings for the hospital. Paola Coppola, MD, ED director at Brookhaven Memorial Hospital Medical Center, says, “From an ER perspective, a call to the hospitalist replaces multiple calls to specialists. In general, hospitalists feel much more comfortable treating a wide array of conditions including infectious disease, pneumonias, strokes, and chest pain without the intervention of specialists in that field. Hence, hospital consumption of resources decreases, which in turn lowers length of stay.” He echoes Rifkin’s thoughts on quick response time. “Hospitalists provide an immediately available service, thus saving ER physicians valuable time. This ensures faster turnover, better throughput, makes more ER beds available, and services more patients, eventually helping the hospital’s bottom line,” says Coppola (8).

In addition to teamwork, 24/7 availability is vital to the wise utilization of resources, according to Anthony Shallash, MD, vice president of medical affairs at Brookhaven. “The fact of 24/7 presence allows rapid responses to patient condition and problems. Continuous and close monitoring of patients allows them to be upgraded or downgraded as needed,” he says. “As such, LOS is decreased and quite favorable as compared to peer practitioners for similar disease severity. Resources consumed and tests ordered also show a favorable trend” (9).

A recently published study (10) by researchers at Dartmouth Medical School documents the variation in the volume and cost of services that academic medical centers use in treating patients. Hospitals were categorized as low- and high-intensity, with significant differences in cost per case. For example, the high-intensity hospitals spent up to 47% more on care for acute myocardial infarction. In an interview in Today’s Hospitalist (11), the lead author, Elliott S. Fisher, MD, professor of medicine and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, described the importance of coordination in achieving efficient care. Fisher says, “I think there’s a real opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of patients in both high- and low- intensity hospitals. Having ten doctors involved in a given patient’s care may not be a good thing, unless someone [i.e., the hospitalist] is doing a really good job of coordinating that care.”

Hospitalists focus only on inpatient medicine. They are familiar with managing the most common medical diagnoses, such as community acquired pneumonia, diabetes. and congestive heart failure. Hospitalist programs often develop uniform and consistent ways of treating these patients. Cogent Healthcare, a national hospitalist management company has implemented the “Cogent Care Guides,” best practice guidelines for high-volume hospital diagnoses. Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP and Cogent’s chief medical officer, says “The Cogent Care Guides ensure best practices are implemented at critical points in the patient’s care… decreasing the variability of care that results in inefficiencies.” Greeno added, “The care guidelines [also] support the timely notification of the primary care physician of nine critical landmark events related to patient status that can affect outcomes” (12).

Stacy Goldsholl, Director of the Covenant HealthCare Hospital Medicine Program in Saginaw, MI, suggests other ways that hospitalists can generate utilization savings for their hospitals. “Hospitalists often eliminate unnecessary admissions and shift work-ups to the ambulatory setting. For example, I recently arranged an outpatient colonoscopy for a pneumonia patient with a stable hemoglobin and heme positive stool. Because of my experience treating patients with pneumonia, I was able to determine that the circumstances did not require an inpatient stay.” In addition, Dr. Goldsholl has found that the hospitalists in her program are quite effective in classifying “observation” patients, eliminating reimbursement conflicts with Medicare, Medicaid, and other insurers.

Finally, because they are always in the hospital rather than sharing time between the office and hospital, hospitalists can improve inpatient continuity of care, resulting in lower costs and better outcomes. Adrienne Bennett, MD, chief of the hospital medicine service at Newton-Wellesley Hospital near Boston, examined cases managed by hospitalists and non-hospitalist community physicians, comparing the number of “handoffs” of responsibility that occur among attending physicians. Community physicians share inpatient responsibility in their practices and sometimes their partners round on their patients. Every time another physician assumes responsibility for a patient, there is the potential for a loss of information and a discontinuity of care. At Newton-Wellesley Hospital, the hospitalists work a schedule of 14 days on, followed by 7 days off. “We found that hospitalists averaged less than half the number of handoffs as the community physicians,” says Bennett. “This may be one of the reasons that hospitalists have better case mix adjusted utilization performance.”

Stakeholder Analysis