User login

Acute Treatment of Hypertensive Urgency

The "Things We Do for No Reason" (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent "black and white" conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 67-year-old man is hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. He has a history of hypertension and is prescribed two antihypertensive medications (amlodipine and chlorthalidone) as an outpatient. On the evening of hospital day two, he is found to have a blood pressure of 192/95 on a scheduled vital signs check. He reports no symptoms other than cough, which is not new or worsening. The covering hospitalist reviews the documented blood pressures since admission and notes that many have been elevated despite continuation of his home regimen. The patient's nurse inquires about treating the patient with additional "as-needed" antihypertensive medications.

BACKGROUND

Hypertensive crises are common in hospitalized patients, with approximately one in seven patients experiencing an episode of hypertensive emergency and/or hypertensive urgency.1 Hypertensive emergency is typically defined as (1) a systolic blood pressure ≥180 mm Hg and/or a diastolic blood pressure ≥120 mm Hg with (2) evidence of new or worsening end-organ damage. The organs most commonly affected by severe hypertension are the brain (headache, confusion, stroke), heart (chest pain, myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema), large blood vessels (aortic dissection), and kidneys (acute hypertensive nephrosclerosis).2 With hypertensive urgency, patients experience similarly elevated blood pressure but have no symptoms or signs suggesting acute end-organ damage. Acute treatment with intravenous (IV) or immediate-acting oral medications is common; a single-center study showed that 7.4% of hospitalized patients had an order for "as needed" IV hydralazine or labetalol, with 60.3% receiving at least one dose.3 Among internal medicine and family medicine trainees in one survey, nearly half reported that they would use IV medications in a scenario where an inpatient had an asymptomatic blood pressure above 180 mm Hg.4

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK TREATING HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY IS NECESSARY

Treating patients with hypertensive urgency is based on an assumption: If one does not treat immediately, something bad (ie, end-organ damage) will occur over the next few hours. Data from the 1930s showed that patients with untreated hypertensive emergency had a one-year mortality rate >79% and a median survival of 10.4 months.5 More recent studies suggest that the in-hospital and one-year mortality for those with hypertensive emergency are 13% and 39%, respectively.6 These data demonstrate that patients with hypertensive emergency are at risk in both the short- and long-term.

Patients with hypertensive urgency are also at increased risk for long-term morbidity and mortality. The one-year mortality for those experiencing an episode of hypertensive urgency is approximately 9%.6 Given the concerns about poor outcomes, it remains a common practice in many facilities to acutely lower the blood pressure in patients with hypertensive urgency. This is highlighted by recommendations of a commonly used point-of-care medical resource, which suggests that "potential legal ramifications partially motivate lowering the blood pressure over several hours."7

WHY TREATING HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY IS UNNECESSARY AND POTENTIALLY HARMFUL

Concerns regarding overtreatment of hypertensive urgency relate to overestimated rates of hypertensive complications, the pathophysiology of hypertension itself, and the potential for adverse events related to treatment. Given that there are few trials examining hospitalized patients with hypertensive urgency, much of the data supporting a conservative approach are drawn from studies of outpatients or emergency department patients. In addition, there is little data suggesting that outcomes are different for patients presenting with a chief complaint of hypertensive urgency and those presenting with an alternate diagnosis but who are found to have blood pressures that meet the threshold for diagnosis of hypertensive urgency.

The landmark 1967 Veterans Affairs Cooperative Trial demonstrated the long-term benefits of treating patients with chronic hypertensive urgency.8 Importantly though, benefits accrued over a period of months to years, not hours. The time to the first adverse event in the placebo arm was two months, suggesting that even those with blood pressures chronically in the range of hypertensive urgency are unlikely to experience hyperacute (ie, within hours) events, even without treatment.

A more recent study, conducted by Patel et al., examined 58,836 patients seen in outpatient clinics and found to have blood pressures meeting the criteria for hypertensive urgency.9 This study included patients whose primary issue was hypertensive urgency and patients in whom the diagnosis was secondary. A total of 426 patients were referred to the hospital and only 100 (0.17%) were subsequently admitted. At seven days, the rates of the primary outcome (a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, and/or transient ischemic attack) were 0.1% in those sent home and 0.5% in those sent to the hospital. In those patients with a systolic blood pressure ≥220 mm Hg, two out of 977 (0.2%) of those sent home and zero out of 81 of those sent to the hospital experienced the primary outcome. These data reinforce the message that, in patients with hypertensive urgency, rates of adverse events at seven days are low, even with extreme blood pressure elevation.

The human body has adapted to withstand wide variations in blood pressure.10 For example, through arteriolar constriction and reflex vasodilation, cerebral autoregulation maintains a constant cerebral blood flow within a wide range of perfusion pressures, ensuring that the brain is protected from higher mean arterial pressures.11 While this process is protective, over time the autoregulatory system becomes impaired, especially in patients with cerebrovascular disease. This places patients at risk for cerebral and/or cardiac ischemia with even slight drops in perfusion pressure.12,13 Indeed, in assessing treatment-related adverse events in a series of patients treated with intravenous nicardipine or nitroprusside for hypertensive emergency, Brooks and colleagues reported that 57% (27 of 47) of patients had overly large reductions in blood pressure (>25% reduction in mean arterial pressure) within the first 30 minutes of treatment.14 Two patients had acute ischemic events attributed to treatment with antihypertensive medications. Myocardial infarction and stroke have both been reported,12 and medication classes such as calcium channel blockers (sublingual nifedipine in particular), beta-blockers (eg, labetolol), angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (eg, captopril), and clonidine have all been implicated in treatment-related adverse events.12,15-17 Another potential issue derives from the observation that blood pressures obtained in the hospital setting are often inaccurate, owing to inappropriate patient preparation, faulty equipment, and inadequate training of staff obtaining the measurement.18

National guidelines support a cautious approach to the treatment of hypertensive urgency. The seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of Hypertension, published in 2003, noted that "patients with markedly elevated BP but without acute target-organ damage usually do not require hospitalization, but they should receive immediate combination oral antihypertensive therapy" and that "there is no evidence to suggest that failure to aggressively lower BP in the [emergency department] is associated with any increased short-term risk to the patient who presents with severe hypertension." JNC 7 also laments contemporary terminology: "Unfortunately, the term 'urgency' has led to overly aggressive management of many patients with severe, uncomplicated hypertension. Aggressive dosing with intravenous drugs or even oral agents, to rapidly lower BP is not without risk."19 The most recent JNC guideline does not comment on hypertensive urgency,20 and the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults argues that, "¬there is no indication for referral to the emergency department, immediate reduction in BP in the emergency department, or hospitalization for [patients with hypertensive urgency]."21

WHAT CLINICIANS SHOULD DO INSTEAD

After it is confirmed that a patient has no end-organ damage (ie, the patient has hypertensive urgency, not emergency), treatable causes of hypertension should be assessed. In hospitalized patients, these include missed or held doses of outpatient medications, pain, nausea, alcohol and/or benzodiazepine withdrawal, delirium, and obstructive sleep apnea.22 If no remediable cause is identified, patients should be allowed to rest for at least 30 minutes without the administration of additional antihypertensive medications, after which time the blood pressure should be measured using the correct technique.2 Clinical trials have shown that rest is effective at lowering blood pressure in patients with hypertensive urgency.23,24 One study initially treated 549 emergency department patients with a 30-minute rest period, after which time 32% of patients had responded (defined as a SBP <180 mm Hg and DBP <110 mm Hg, with at least a 20 mm Hg reduction in baseline SBP and/or a 10 mm Hg reduction in DBP).23 Another study randomized 138 patients with hypertensive urgency to either rest or active treatment with telmisartan. Blood pressures were checked every 30 minutes for four hours. The primary endpoint (reduction of MAP of 10%-35%) was similar in both groups (68.5% in the rest group and 69.1% in the telmisartan group).24 Even if rest is ineffective, the risk-benefit ratio of acutely lowering blood pressure will typically favor withholding acute treatment in asymptomatic patients. If blood pressure remains consistently elevated, augmentation of the home regimen (eg, increasing the dose of their next scheduled antihypertensive) of oral medications may be warranted. Though not all agree with management of antihypertensives in hospitalized patients,25 acute hospitalizations afford an opportunity to modify and observe chronic hypertension.26

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ensure that patients do not have symptoms and/or signs of end-organ damage. This can be done with a brief review of systems and a physical examination. In select cases, an electrocardiogram and a chest x-ray may be warranted.

- Search for common causes of treatable hypertension in hospitalized patients; these include pain, nausea, withdrawal syndromes, and holding of usual antihypertensive medications.

- In those patients without symptoms and/or signs of end-organ damage, allow rest, followed by reassessment.

- Do not administer intravenous or immediate-acting oral antihypertensive medications to acutely lower blood pressure. Instead, address the issues raised in Recommendation #2 and consider modifying the chronic oral antihypertensive regimen in patients who are uncontrolled as outpatients or who are not treated as outpatients. Coordinate early postdischarge follow-up for repeat blood pressure evaluation and continued modification of a patient's chronic antihypertensive regimen.

CONCLUSION

Although patients with hypertensive urgency are often treated with medications to acutely lower their blood pressure, there is no evidence to support this practice, and a strong pathophysiologic basis suggests that harm may result. The patient in the case described above should be allowed to rest for at least 30 minutes, with reevaluation of his blood pressure. If it remains elevated and no treatable secondary causes are found, the treating hospitalist should consider altering his chronic antihypertensive regimen to promote long-term blood pressure control.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a "Thing We Do for No Reason?" Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other "Things We Do for No Reason" topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

1. Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Sun X, et al. Severe acute hypertension among inpatients admitted from the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):203-210. doi: 10.1002/jhm.969. PubMed

2. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of High blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2017. PubMed

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(1):29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x. PubMed

4. Axon RN, Garrell R, Pfahl K, et al. Attitudes and practices of resident physicians regarding hypertension in the inpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(9):698-705. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00309.x. PubMed

5. Keith NM, Wagener HP, Barker NW. Some different types of essential hypertension: their course and prognosis. Am J Med Sci. 1974;268(6):336-345. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197412000-00004. PubMed

6. Guiga H, Decroux C, Michelet P, et al. Hospital and out-of-hospital mortality in 670 hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(11):1137-1142. doi: 10.1111/jch.13083. PubMed

7. Varon J, Williams EJ. Management of severe asymptomatic hypertension (hypertensive urgencies) in adults. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed February 13, 2018). PubMed

8. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. JAMA. 1967;202(11):1028-1034. soi: 10.1001/jama.1967.03130240070013 PubMed

9. Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):981-988. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1509. PubMed

10. MacDougall JD, Tuxen D, Sale DG, Moroz JR, Sutton JR. Arterial blood pressure response to heavy resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1985;58(3):785-790. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.3.785. PubMed

11. Strandgaard S, Olesen J, Skinhoj E, Lassen NA. Autoregulation of brain circulation in severe arterial hypertension. Br Med J. 1973;1(5852):507-510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5852.507. PubMed

12. Fischberg GM, Lozano E, Rajamani K, Ameriso S, Fisher MJ. Stroke precipitated by moderate blood pressure reduction. J Emerg Med. 2000;19(4):339-346. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(00)00267-5. PubMed

13. Ross RS. Pathophysiology of coronary circulation. Br Heart J. 1971;33(2):173-184. doi: 10.1136/hrt.33.2.173. PubMed

14. Brooks TW, Finch CK, Lobo BL, Deaton PR, Varner CF. Blood pressure management in acute hypertensive emergency. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(24):2579-2582. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070105. PubMed

15. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, Kowey P. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-1331. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540160050032 PubMed

16. Hodsman GP, Isles CG, Murray GD et al. Factors related to first dose hypotensive effect of captopril: prediction and treatment. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286(6368):832-834. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6368.832. PubMed

17. Zeller KR, Von Kuhnert L, Matthews C. Rapid reduction of severe asymptomatic hypertension. A prospective, controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(10):2186-2189. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.10.2186. PubMed

18. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111(5):697-716. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154900.76284.F6. PubMed

19. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560-2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. PubMed

20. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 PubMed

21. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of High blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017. PubMed

22. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0648-y. PubMed

23. Grassi D, O'Flaherty M, Pellizzari M, et al. Hypertensive urgencies in the emergency department: evaluating blood pressure response to rest and to antihypertensive drugs with different profiles. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(9):662-667. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00001.x. PubMed

24. Park SK, Lee DY, Kim WJ, et al. Comparing the clinical efficacy of resting and antihypertensive medication in patients of hypertensive urgency: a randomized, control trial. J Hypertens. 2017;35(7):1474-1480. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001340. PubMed

25. Steinman MA, Auerbach AD. Managing chronic disease in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1857-1858. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9511. PubMed

26. Breu AC, Allen-Dicker J, Mueller S et al. Hospitalist and primary care physician perspectives on medication management of chronic conditions for hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):303-309. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2137. PubMed

The "Things We Do for No Reason" (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent "black and white" conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 67-year-old man is hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. He has a history of hypertension and is prescribed two antihypertensive medications (amlodipine and chlorthalidone) as an outpatient. On the evening of hospital day two, he is found to have a blood pressure of 192/95 on a scheduled vital signs check. He reports no symptoms other than cough, which is not new or worsening. The covering hospitalist reviews the documented blood pressures since admission and notes that many have been elevated despite continuation of his home regimen. The patient's nurse inquires about treating the patient with additional "as-needed" antihypertensive medications.

BACKGROUND

Hypertensive crises are common in hospitalized patients, with approximately one in seven patients experiencing an episode of hypertensive emergency and/or hypertensive urgency.1 Hypertensive emergency is typically defined as (1) a systolic blood pressure ≥180 mm Hg and/or a diastolic blood pressure ≥120 mm Hg with (2) evidence of new or worsening end-organ damage. The organs most commonly affected by severe hypertension are the brain (headache, confusion, stroke), heart (chest pain, myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema), large blood vessels (aortic dissection), and kidneys (acute hypertensive nephrosclerosis).2 With hypertensive urgency, patients experience similarly elevated blood pressure but have no symptoms or signs suggesting acute end-organ damage. Acute treatment with intravenous (IV) or immediate-acting oral medications is common; a single-center study showed that 7.4% of hospitalized patients had an order for "as needed" IV hydralazine or labetalol, with 60.3% receiving at least one dose.3 Among internal medicine and family medicine trainees in one survey, nearly half reported that they would use IV medications in a scenario where an inpatient had an asymptomatic blood pressure above 180 mm Hg.4

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK TREATING HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY IS NECESSARY

Treating patients with hypertensive urgency is based on an assumption: If one does not treat immediately, something bad (ie, end-organ damage) will occur over the next few hours. Data from the 1930s showed that patients with untreated hypertensive emergency had a one-year mortality rate >79% and a median survival of 10.4 months.5 More recent studies suggest that the in-hospital and one-year mortality for those with hypertensive emergency are 13% and 39%, respectively.6 These data demonstrate that patients with hypertensive emergency are at risk in both the short- and long-term.

Patients with hypertensive urgency are also at increased risk for long-term morbidity and mortality. The one-year mortality for those experiencing an episode of hypertensive urgency is approximately 9%.6 Given the concerns about poor outcomes, it remains a common practice in many facilities to acutely lower the blood pressure in patients with hypertensive urgency. This is highlighted by recommendations of a commonly used point-of-care medical resource, which suggests that "potential legal ramifications partially motivate lowering the blood pressure over several hours."7

WHY TREATING HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY IS UNNECESSARY AND POTENTIALLY HARMFUL

Concerns regarding overtreatment of hypertensive urgency relate to overestimated rates of hypertensive complications, the pathophysiology of hypertension itself, and the potential for adverse events related to treatment. Given that there are few trials examining hospitalized patients with hypertensive urgency, much of the data supporting a conservative approach are drawn from studies of outpatients or emergency department patients. In addition, there is little data suggesting that outcomes are different for patients presenting with a chief complaint of hypertensive urgency and those presenting with an alternate diagnosis but who are found to have blood pressures that meet the threshold for diagnosis of hypertensive urgency.

The landmark 1967 Veterans Affairs Cooperative Trial demonstrated the long-term benefits of treating patients with chronic hypertensive urgency.8 Importantly though, benefits accrued over a period of months to years, not hours. The time to the first adverse event in the placebo arm was two months, suggesting that even those with blood pressures chronically in the range of hypertensive urgency are unlikely to experience hyperacute (ie, within hours) events, even without treatment.

A more recent study, conducted by Patel et al., examined 58,836 patients seen in outpatient clinics and found to have blood pressures meeting the criteria for hypertensive urgency.9 This study included patients whose primary issue was hypertensive urgency and patients in whom the diagnosis was secondary. A total of 426 patients were referred to the hospital and only 100 (0.17%) were subsequently admitted. At seven days, the rates of the primary outcome (a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, and/or transient ischemic attack) were 0.1% in those sent home and 0.5% in those sent to the hospital. In those patients with a systolic blood pressure ≥220 mm Hg, two out of 977 (0.2%) of those sent home and zero out of 81 of those sent to the hospital experienced the primary outcome. These data reinforce the message that, in patients with hypertensive urgency, rates of adverse events at seven days are low, even with extreme blood pressure elevation.

The human body has adapted to withstand wide variations in blood pressure.10 For example, through arteriolar constriction and reflex vasodilation, cerebral autoregulation maintains a constant cerebral blood flow within a wide range of perfusion pressures, ensuring that the brain is protected from higher mean arterial pressures.11 While this process is protective, over time the autoregulatory system becomes impaired, especially in patients with cerebrovascular disease. This places patients at risk for cerebral and/or cardiac ischemia with even slight drops in perfusion pressure.12,13 Indeed, in assessing treatment-related adverse events in a series of patients treated with intravenous nicardipine or nitroprusside for hypertensive emergency, Brooks and colleagues reported that 57% (27 of 47) of patients had overly large reductions in blood pressure (>25% reduction in mean arterial pressure) within the first 30 minutes of treatment.14 Two patients had acute ischemic events attributed to treatment with antihypertensive medications. Myocardial infarction and stroke have both been reported,12 and medication classes such as calcium channel blockers (sublingual nifedipine in particular), beta-blockers (eg, labetolol), angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (eg, captopril), and clonidine have all been implicated in treatment-related adverse events.12,15-17 Another potential issue derives from the observation that blood pressures obtained in the hospital setting are often inaccurate, owing to inappropriate patient preparation, faulty equipment, and inadequate training of staff obtaining the measurement.18

National guidelines support a cautious approach to the treatment of hypertensive urgency. The seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of Hypertension, published in 2003, noted that "patients with markedly elevated BP but without acute target-organ damage usually do not require hospitalization, but they should receive immediate combination oral antihypertensive therapy" and that "there is no evidence to suggest that failure to aggressively lower BP in the [emergency department] is associated with any increased short-term risk to the patient who presents with severe hypertension." JNC 7 also laments contemporary terminology: "Unfortunately, the term 'urgency' has led to overly aggressive management of many patients with severe, uncomplicated hypertension. Aggressive dosing with intravenous drugs or even oral agents, to rapidly lower BP is not without risk."19 The most recent JNC guideline does not comment on hypertensive urgency,20 and the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults argues that, "¬there is no indication for referral to the emergency department, immediate reduction in BP in the emergency department, or hospitalization for [patients with hypertensive urgency]."21

WHAT CLINICIANS SHOULD DO INSTEAD

After it is confirmed that a patient has no end-organ damage (ie, the patient has hypertensive urgency, not emergency), treatable causes of hypertension should be assessed. In hospitalized patients, these include missed or held doses of outpatient medications, pain, nausea, alcohol and/or benzodiazepine withdrawal, delirium, and obstructive sleep apnea.22 If no remediable cause is identified, patients should be allowed to rest for at least 30 minutes without the administration of additional antihypertensive medications, after which time the blood pressure should be measured using the correct technique.2 Clinical trials have shown that rest is effective at lowering blood pressure in patients with hypertensive urgency.23,24 One study initially treated 549 emergency department patients with a 30-minute rest period, after which time 32% of patients had responded (defined as a SBP <180 mm Hg and DBP <110 mm Hg, with at least a 20 mm Hg reduction in baseline SBP and/or a 10 mm Hg reduction in DBP).23 Another study randomized 138 patients with hypertensive urgency to either rest or active treatment with telmisartan. Blood pressures were checked every 30 minutes for four hours. The primary endpoint (reduction of MAP of 10%-35%) was similar in both groups (68.5% in the rest group and 69.1% in the telmisartan group).24 Even if rest is ineffective, the risk-benefit ratio of acutely lowering blood pressure will typically favor withholding acute treatment in asymptomatic patients. If blood pressure remains consistently elevated, augmentation of the home regimen (eg, increasing the dose of their next scheduled antihypertensive) of oral medications may be warranted. Though not all agree with management of antihypertensives in hospitalized patients,25 acute hospitalizations afford an opportunity to modify and observe chronic hypertension.26

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ensure that patients do not have symptoms and/or signs of end-organ damage. This can be done with a brief review of systems and a physical examination. In select cases, an electrocardiogram and a chest x-ray may be warranted.

- Search for common causes of treatable hypertension in hospitalized patients; these include pain, nausea, withdrawal syndromes, and holding of usual antihypertensive medications.

- In those patients without symptoms and/or signs of end-organ damage, allow rest, followed by reassessment.

- Do not administer intravenous or immediate-acting oral antihypertensive medications to acutely lower blood pressure. Instead, address the issues raised in Recommendation #2 and consider modifying the chronic oral antihypertensive regimen in patients who are uncontrolled as outpatients or who are not treated as outpatients. Coordinate early postdischarge follow-up for repeat blood pressure evaluation and continued modification of a patient's chronic antihypertensive regimen.

CONCLUSION

Although patients with hypertensive urgency are often treated with medications to acutely lower their blood pressure, there is no evidence to support this practice, and a strong pathophysiologic basis suggests that harm may result. The patient in the case described above should be allowed to rest for at least 30 minutes, with reevaluation of his blood pressure. If it remains elevated and no treatable secondary causes are found, the treating hospitalist should consider altering his chronic antihypertensive regimen to promote long-term blood pressure control.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a "Thing We Do for No Reason?" Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other "Things We Do for No Reason" topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

The "Things We Do for No Reason" (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent "black and white" conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 67-year-old man is hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. He has a history of hypertension and is prescribed two antihypertensive medications (amlodipine and chlorthalidone) as an outpatient. On the evening of hospital day two, he is found to have a blood pressure of 192/95 on a scheduled vital signs check. He reports no symptoms other than cough, which is not new or worsening. The covering hospitalist reviews the documented blood pressures since admission and notes that many have been elevated despite continuation of his home regimen. The patient's nurse inquires about treating the patient with additional "as-needed" antihypertensive medications.

BACKGROUND

Hypertensive crises are common in hospitalized patients, with approximately one in seven patients experiencing an episode of hypertensive emergency and/or hypertensive urgency.1 Hypertensive emergency is typically defined as (1) a systolic blood pressure ≥180 mm Hg and/or a diastolic blood pressure ≥120 mm Hg with (2) evidence of new or worsening end-organ damage. The organs most commonly affected by severe hypertension are the brain (headache, confusion, stroke), heart (chest pain, myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema), large blood vessels (aortic dissection), and kidneys (acute hypertensive nephrosclerosis).2 With hypertensive urgency, patients experience similarly elevated blood pressure but have no symptoms or signs suggesting acute end-organ damage. Acute treatment with intravenous (IV) or immediate-acting oral medications is common; a single-center study showed that 7.4% of hospitalized patients had an order for "as needed" IV hydralazine or labetalol, with 60.3% receiving at least one dose.3 Among internal medicine and family medicine trainees in one survey, nearly half reported that they would use IV medications in a scenario where an inpatient had an asymptomatic blood pressure above 180 mm Hg.4

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK TREATING HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY IS NECESSARY

Treating patients with hypertensive urgency is based on an assumption: If one does not treat immediately, something bad (ie, end-organ damage) will occur over the next few hours. Data from the 1930s showed that patients with untreated hypertensive emergency had a one-year mortality rate >79% and a median survival of 10.4 months.5 More recent studies suggest that the in-hospital and one-year mortality for those with hypertensive emergency are 13% and 39%, respectively.6 These data demonstrate that patients with hypertensive emergency are at risk in both the short- and long-term.

Patients with hypertensive urgency are also at increased risk for long-term morbidity and mortality. The one-year mortality for those experiencing an episode of hypertensive urgency is approximately 9%.6 Given the concerns about poor outcomes, it remains a common practice in many facilities to acutely lower the blood pressure in patients with hypertensive urgency. This is highlighted by recommendations of a commonly used point-of-care medical resource, which suggests that "potential legal ramifications partially motivate lowering the blood pressure over several hours."7

WHY TREATING HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY IS UNNECESSARY AND POTENTIALLY HARMFUL

Concerns regarding overtreatment of hypertensive urgency relate to overestimated rates of hypertensive complications, the pathophysiology of hypertension itself, and the potential for adverse events related to treatment. Given that there are few trials examining hospitalized patients with hypertensive urgency, much of the data supporting a conservative approach are drawn from studies of outpatients or emergency department patients. In addition, there is little data suggesting that outcomes are different for patients presenting with a chief complaint of hypertensive urgency and those presenting with an alternate diagnosis but who are found to have blood pressures that meet the threshold for diagnosis of hypertensive urgency.

The landmark 1967 Veterans Affairs Cooperative Trial demonstrated the long-term benefits of treating patients with chronic hypertensive urgency.8 Importantly though, benefits accrued over a period of months to years, not hours. The time to the first adverse event in the placebo arm was two months, suggesting that even those with blood pressures chronically in the range of hypertensive urgency are unlikely to experience hyperacute (ie, within hours) events, even without treatment.

A more recent study, conducted by Patel et al., examined 58,836 patients seen in outpatient clinics and found to have blood pressures meeting the criteria for hypertensive urgency.9 This study included patients whose primary issue was hypertensive urgency and patients in whom the diagnosis was secondary. A total of 426 patients were referred to the hospital and only 100 (0.17%) were subsequently admitted. At seven days, the rates of the primary outcome (a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, and/or transient ischemic attack) were 0.1% in those sent home and 0.5% in those sent to the hospital. In those patients with a systolic blood pressure ≥220 mm Hg, two out of 977 (0.2%) of those sent home and zero out of 81 of those sent to the hospital experienced the primary outcome. These data reinforce the message that, in patients with hypertensive urgency, rates of adverse events at seven days are low, even with extreme blood pressure elevation.

The human body has adapted to withstand wide variations in blood pressure.10 For example, through arteriolar constriction and reflex vasodilation, cerebral autoregulation maintains a constant cerebral blood flow within a wide range of perfusion pressures, ensuring that the brain is protected from higher mean arterial pressures.11 While this process is protective, over time the autoregulatory system becomes impaired, especially in patients with cerebrovascular disease. This places patients at risk for cerebral and/or cardiac ischemia with even slight drops in perfusion pressure.12,13 Indeed, in assessing treatment-related adverse events in a series of patients treated with intravenous nicardipine or nitroprusside for hypertensive emergency, Brooks and colleagues reported that 57% (27 of 47) of patients had overly large reductions in blood pressure (>25% reduction in mean arterial pressure) within the first 30 minutes of treatment.14 Two patients had acute ischemic events attributed to treatment with antihypertensive medications. Myocardial infarction and stroke have both been reported,12 and medication classes such as calcium channel blockers (sublingual nifedipine in particular), beta-blockers (eg, labetolol), angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (eg, captopril), and clonidine have all been implicated in treatment-related adverse events.12,15-17 Another potential issue derives from the observation that blood pressures obtained in the hospital setting are often inaccurate, owing to inappropriate patient preparation, faulty equipment, and inadequate training of staff obtaining the measurement.18

National guidelines support a cautious approach to the treatment of hypertensive urgency. The seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of Hypertension, published in 2003, noted that "patients with markedly elevated BP but without acute target-organ damage usually do not require hospitalization, but they should receive immediate combination oral antihypertensive therapy" and that "there is no evidence to suggest that failure to aggressively lower BP in the [emergency department] is associated with any increased short-term risk to the patient who presents with severe hypertension." JNC 7 also laments contemporary terminology: "Unfortunately, the term 'urgency' has led to overly aggressive management of many patients with severe, uncomplicated hypertension. Aggressive dosing with intravenous drugs or even oral agents, to rapidly lower BP is not without risk."19 The most recent JNC guideline does not comment on hypertensive urgency,20 and the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults argues that, "¬there is no indication for referral to the emergency department, immediate reduction in BP in the emergency department, or hospitalization for [patients with hypertensive urgency]."21

WHAT CLINICIANS SHOULD DO INSTEAD

After it is confirmed that a patient has no end-organ damage (ie, the patient has hypertensive urgency, not emergency), treatable causes of hypertension should be assessed. In hospitalized patients, these include missed or held doses of outpatient medications, pain, nausea, alcohol and/or benzodiazepine withdrawal, delirium, and obstructive sleep apnea.22 If no remediable cause is identified, patients should be allowed to rest for at least 30 minutes without the administration of additional antihypertensive medications, after which time the blood pressure should be measured using the correct technique.2 Clinical trials have shown that rest is effective at lowering blood pressure in patients with hypertensive urgency.23,24 One study initially treated 549 emergency department patients with a 30-minute rest period, after which time 32% of patients had responded (defined as a SBP <180 mm Hg and DBP <110 mm Hg, with at least a 20 mm Hg reduction in baseline SBP and/or a 10 mm Hg reduction in DBP).23 Another study randomized 138 patients with hypertensive urgency to either rest or active treatment with telmisartan. Blood pressures were checked every 30 minutes for four hours. The primary endpoint (reduction of MAP of 10%-35%) was similar in both groups (68.5% in the rest group and 69.1% in the telmisartan group).24 Even if rest is ineffective, the risk-benefit ratio of acutely lowering blood pressure will typically favor withholding acute treatment in asymptomatic patients. If blood pressure remains consistently elevated, augmentation of the home regimen (eg, increasing the dose of their next scheduled antihypertensive) of oral medications may be warranted. Though not all agree with management of antihypertensives in hospitalized patients,25 acute hospitalizations afford an opportunity to modify and observe chronic hypertension.26

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ensure that patients do not have symptoms and/or signs of end-organ damage. This can be done with a brief review of systems and a physical examination. In select cases, an electrocardiogram and a chest x-ray may be warranted.

- Search for common causes of treatable hypertension in hospitalized patients; these include pain, nausea, withdrawal syndromes, and holding of usual antihypertensive medications.

- In those patients without symptoms and/or signs of end-organ damage, allow rest, followed by reassessment.

- Do not administer intravenous or immediate-acting oral antihypertensive medications to acutely lower blood pressure. Instead, address the issues raised in Recommendation #2 and consider modifying the chronic oral antihypertensive regimen in patients who are uncontrolled as outpatients or who are not treated as outpatients. Coordinate early postdischarge follow-up for repeat blood pressure evaluation and continued modification of a patient's chronic antihypertensive regimen.

CONCLUSION

Although patients with hypertensive urgency are often treated with medications to acutely lower their blood pressure, there is no evidence to support this practice, and a strong pathophysiologic basis suggests that harm may result. The patient in the case described above should be allowed to rest for at least 30 minutes, with reevaluation of his blood pressure. If it remains elevated and no treatable secondary causes are found, the treating hospitalist should consider altering his chronic antihypertensive regimen to promote long-term blood pressure control.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a "Thing We Do for No Reason?" Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other "Things We Do for No Reason" topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

1. Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Sun X, et al. Severe acute hypertension among inpatients admitted from the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):203-210. doi: 10.1002/jhm.969. PubMed

2. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of High blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2017. PubMed

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(1):29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x. PubMed

4. Axon RN, Garrell R, Pfahl K, et al. Attitudes and practices of resident physicians regarding hypertension in the inpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(9):698-705. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00309.x. PubMed

5. Keith NM, Wagener HP, Barker NW. Some different types of essential hypertension: their course and prognosis. Am J Med Sci. 1974;268(6):336-345. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197412000-00004. PubMed

6. Guiga H, Decroux C, Michelet P, et al. Hospital and out-of-hospital mortality in 670 hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(11):1137-1142. doi: 10.1111/jch.13083. PubMed

7. Varon J, Williams EJ. Management of severe asymptomatic hypertension (hypertensive urgencies) in adults. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed February 13, 2018). PubMed

8. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. JAMA. 1967;202(11):1028-1034. soi: 10.1001/jama.1967.03130240070013 PubMed

9. Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):981-988. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1509. PubMed

10. MacDougall JD, Tuxen D, Sale DG, Moroz JR, Sutton JR. Arterial blood pressure response to heavy resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1985;58(3):785-790. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.3.785. PubMed

11. Strandgaard S, Olesen J, Skinhoj E, Lassen NA. Autoregulation of brain circulation in severe arterial hypertension. Br Med J. 1973;1(5852):507-510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5852.507. PubMed

12. Fischberg GM, Lozano E, Rajamani K, Ameriso S, Fisher MJ. Stroke precipitated by moderate blood pressure reduction. J Emerg Med. 2000;19(4):339-346. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(00)00267-5. PubMed

13. Ross RS. Pathophysiology of coronary circulation. Br Heart J. 1971;33(2):173-184. doi: 10.1136/hrt.33.2.173. PubMed

14. Brooks TW, Finch CK, Lobo BL, Deaton PR, Varner CF. Blood pressure management in acute hypertensive emergency. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(24):2579-2582. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070105. PubMed

15. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, Kowey P. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-1331. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540160050032 PubMed

16. Hodsman GP, Isles CG, Murray GD et al. Factors related to first dose hypotensive effect of captopril: prediction and treatment. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286(6368):832-834. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6368.832. PubMed

17. Zeller KR, Von Kuhnert L, Matthews C. Rapid reduction of severe asymptomatic hypertension. A prospective, controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(10):2186-2189. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.10.2186. PubMed

18. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111(5):697-716. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154900.76284.F6. PubMed

19. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560-2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. PubMed

20. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 PubMed

21. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of High blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017. PubMed

22. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0648-y. PubMed

23. Grassi D, O'Flaherty M, Pellizzari M, et al. Hypertensive urgencies in the emergency department: evaluating blood pressure response to rest and to antihypertensive drugs with different profiles. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(9):662-667. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00001.x. PubMed

24. Park SK, Lee DY, Kim WJ, et al. Comparing the clinical efficacy of resting and antihypertensive medication in patients of hypertensive urgency: a randomized, control trial. J Hypertens. 2017;35(7):1474-1480. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001340. PubMed

25. Steinman MA, Auerbach AD. Managing chronic disease in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1857-1858. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9511. PubMed

26. Breu AC, Allen-Dicker J, Mueller S et al. Hospitalist and primary care physician perspectives on medication management of chronic conditions for hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):303-309. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2137. PubMed

1. Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Sun X, et al. Severe acute hypertension among inpatients admitted from the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):203-210. doi: 10.1002/jhm.969. PubMed

2. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of High blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2017. PubMed

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(1):29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x. PubMed

4. Axon RN, Garrell R, Pfahl K, et al. Attitudes and practices of resident physicians regarding hypertension in the inpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(9):698-705. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00309.x. PubMed

5. Keith NM, Wagener HP, Barker NW. Some different types of essential hypertension: their course and prognosis. Am J Med Sci. 1974;268(6):336-345. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197412000-00004. PubMed

6. Guiga H, Decroux C, Michelet P, et al. Hospital and out-of-hospital mortality in 670 hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(11):1137-1142. doi: 10.1111/jch.13083. PubMed

7. Varon J, Williams EJ. Management of severe asymptomatic hypertension (hypertensive urgencies) in adults. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed February 13, 2018). PubMed

8. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. JAMA. 1967;202(11):1028-1034. soi: 10.1001/jama.1967.03130240070013 PubMed

9. Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):981-988. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1509. PubMed

10. MacDougall JD, Tuxen D, Sale DG, Moroz JR, Sutton JR. Arterial blood pressure response to heavy resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1985;58(3):785-790. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.3.785. PubMed

11. Strandgaard S, Olesen J, Skinhoj E, Lassen NA. Autoregulation of brain circulation in severe arterial hypertension. Br Med J. 1973;1(5852):507-510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5852.507. PubMed

12. Fischberg GM, Lozano E, Rajamani K, Ameriso S, Fisher MJ. Stroke precipitated by moderate blood pressure reduction. J Emerg Med. 2000;19(4):339-346. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(00)00267-5. PubMed

13. Ross RS. Pathophysiology of coronary circulation. Br Heart J. 1971;33(2):173-184. doi: 10.1136/hrt.33.2.173. PubMed

14. Brooks TW, Finch CK, Lobo BL, Deaton PR, Varner CF. Blood pressure management in acute hypertensive emergency. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(24):2579-2582. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070105. PubMed

15. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, Kowey P. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-1331. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540160050032 PubMed

16. Hodsman GP, Isles CG, Murray GD et al. Factors related to first dose hypotensive effect of captopril: prediction and treatment. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286(6368):832-834. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6368.832. PubMed

17. Zeller KR, Von Kuhnert L, Matthews C. Rapid reduction of severe asymptomatic hypertension. A prospective, controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(10):2186-2189. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.10.2186. PubMed

18. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111(5):697-716. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154900.76284.F6. PubMed

19. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560-2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. PubMed

20. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 PubMed

21. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of High blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017. PubMed

22. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0648-y. PubMed

23. Grassi D, O'Flaherty M, Pellizzari M, et al. Hypertensive urgencies in the emergency department: evaluating blood pressure response to rest and to antihypertensive drugs with different profiles. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(9):662-667. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00001.x. PubMed

24. Park SK, Lee DY, Kim WJ, et al. Comparing the clinical efficacy of resting and antihypertensive medication in patients of hypertensive urgency: a randomized, control trial. J Hypertens. 2017;35(7):1474-1480. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001340. PubMed

25. Steinman MA, Auerbach AD. Managing chronic disease in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1857-1858. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9511. PubMed

26. Breu AC, Allen-Dicker J, Mueller S et al. Hospitalist and primary care physician perspectives on medication management of chronic conditions for hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):303-309. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2137. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review

If you wish to receive credit for this activity, please refer to the website:

Accreditation and Designation Statement

Blackwell Futura Media Services designates this journal‐based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit.. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Blackwell Futura Media Services is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Educational Objectives

The objectives need to be changed. Please remove the existing ones, and include these two:

-

To describe the correlation between inpatient and outpatient blood pressure measurements.

-

To assess the potential benefits of prescribing antihypertensive medication in hospitalized patients with hypertension.

This manuscript underwent peer review in line with the standards of editorial integrity and publication ethics maintained by Journal of Hospital Medicine. The peer reviewers have no relevant financial relationships. The peer review process for Journal of Hospital Medicine is single‐blinded. As such, the identities of the reviewers are not disclosed in line with the standard accepted practices of medical journal peer review.

Conflicts of interest have been identified and resolved in accordance with Blackwell Futura Media Services's Policy on Activity Disclosure and Conflict of Interest. The primary resolution method used was peer review and review by a non‐conflicted expert.

Instructions on Receiving Credit

For information on applicability and acceptance of CME credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board.

This activity is designed to be completed within an hour; physicians should claim only those credits that reflect the time actually spent in the activity. To successfully earn credit, participants must complete the activity during the valid credit period, which is up to two years from initial publication.

Follow these steps to earn credit:

-

Log on to www.wileyblackwellcme.com

-

Read the target audience, learning objectives, and author disclosures.

-

Read the article in print or online format.

-

Reflect on the article.

-

Access the CME Exam, and choose the best answer to each question.

-

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

This activity will be available for CME credit for twelve months following its publication date. At that time, it will be reviewed and potentially updated and extended for an additional twelve months.

If you wish to receive credit for this activity, please refer to the website:

Accreditation and Designation Statement

Blackwell Futura Media Services designates this journal‐based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit.. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Blackwell Futura Media Services is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Educational Objectives

The objectives need to be changed. Please remove the existing ones, and include these two:

-

To describe the correlation between inpatient and outpatient blood pressure measurements.

-

To assess the potential benefits of prescribing antihypertensive medication in hospitalized patients with hypertension.

This manuscript underwent peer review in line with the standards of editorial integrity and publication ethics maintained by Journal of Hospital Medicine. The peer reviewers have no relevant financial relationships. The peer review process for Journal of Hospital Medicine is single‐blinded. As such, the identities of the reviewers are not disclosed in line with the standard accepted practices of medical journal peer review.

Conflicts of interest have been identified and resolved in accordance with Blackwell Futura Media Services's Policy on Activity Disclosure and Conflict of Interest. The primary resolution method used was peer review and review by a non‐conflicted expert.

Instructions on Receiving Credit

For information on applicability and acceptance of CME credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board.

This activity is designed to be completed within an hour; physicians should claim only those credits that reflect the time actually spent in the activity. To successfully earn credit, participants must complete the activity during the valid credit period, which is up to two years from initial publication.

Follow these steps to earn credit:

-

Log on to www.wileyblackwellcme.com

-

Read the target audience, learning objectives, and author disclosures.

-

Read the article in print or online format.

-

Reflect on the article.

-

Access the CME Exam, and choose the best answer to each question.

-

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

This activity will be available for CME credit for twelve months following its publication date. At that time, it will be reviewed and potentially updated and extended for an additional twelve months.

If you wish to receive credit for this activity, please refer to the website:

Accreditation and Designation Statement

Blackwell Futura Media Services designates this journal‐based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit.. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Blackwell Futura Media Services is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Educational Objectives

The objectives need to be changed. Please remove the existing ones, and include these two:

-

To describe the correlation between inpatient and outpatient blood pressure measurements.

-

To assess the potential benefits of prescribing antihypertensive medication in hospitalized patients with hypertension.

This manuscript underwent peer review in line with the standards of editorial integrity and publication ethics maintained by Journal of Hospital Medicine. The peer reviewers have no relevant financial relationships. The peer review process for Journal of Hospital Medicine is single‐blinded. As such, the identities of the reviewers are not disclosed in line with the standard accepted practices of medical journal peer review.

Conflicts of interest have been identified and resolved in accordance with Blackwell Futura Media Services's Policy on Activity Disclosure and Conflict of Interest. The primary resolution method used was peer review and review by a non‐conflicted expert.

Instructions on Receiving Credit

For information on applicability and acceptance of CME credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board.

This activity is designed to be completed within an hour; physicians should claim only those credits that reflect the time actually spent in the activity. To successfully earn credit, participants must complete the activity during the valid credit period, which is up to two years from initial publication.

Follow these steps to earn credit:

-

Log on to www.wileyblackwellcme.com

-

Read the target audience, learning objectives, and author disclosures.

-

Read the article in print or online format.

-

Reflect on the article.

-

Access the CME Exam, and choose the best answer to each question.

-

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

This activity will be available for CME credit for twelve months following its publication date. At that time, it will be reviewed and potentially updated and extended for an additional twelve months.

Inpatient Hypertension Review

Hypertension (HTN) is highly prevalent in the general adult population with recent estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 29% in the United States.1, 2 The relationship between increasing levels of blood pressure (BP) and increasing risk for cardiovascular disease events and stroke is well established.3 However, while 64% of treated HTN patients have a BP <140/<90 mmHg, overall control rates for HTN in the adult population remain at approximately 44%.2 The 20% discrepancy in control rates between treated patients and the overall adult population reflects the fact that approximately 30% of patients are unaware of their HTN and that a substantial proportion of aware patients remain untreated. Historically, efforts to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN have appropriately focused on the outpatient setting. However, programs to extend screening for HTN outside the clinic into the community, schools, and even dentists' offices have been around for some time.49

The potential also exists to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN by focusing on hospitalized patients. Hospitalization is common in the U.S. with almost 35 million acute hospitalizations and more than 45,000 inpatient surgical procedures in 2006.10 Inpatient populations have increased in age and comorbidity over the past 3 decades whereas lengths of stay and continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient arenas have diminished.10, 11 Multiple prior studies examining BP in different settings have noted that average BP among hospitalized patients is not systematically higher than that of outpatients.1214 Thus, patients with persistently elevated BP in the inpatient setting without mitigating factors may have HTN that will persist after hospital discharge. However, little information is available regarding the actual prevalence of HTN in the inpatient population and care patterns for inpatient HTN. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the English‐language medical literature in order to describe the epidemiology of HTN observed in the inpatient setting.

Methods

Our search strategy was designed to identify randomized‐controlled trials, meta‐analyses, and observational studies that: (1) reported estimates of the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting, and (2) used HTN diagnosis or treatment as a primary focus. We performed an extensive review of the peer‐reviewed, English language medical literature in MEDLINE using a predetermined search algorithm. Search terms included HTN[Mesh] or BP[Mesh]. These results were cross‐referenced with the following search terms: Inpatients[Mesh] or Hospitalization[title/abstract] or Hospitalized[title/abstract]. Articles were further narrowed using the following terms: Prevalence[Mesh] or Epidemiology[Mesh] or Treatment[title/abstract] or Management [title/abstract]. Limits employed included limiting to humans and to adults 19 years‐of‐age and older. Studies published prior to 1976 were excluded because 1976 was the first year that the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High BP published consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HTN. We also excluded randomized, controlled trials that recorded measures of inpatient BP but whose focus was not HTN, because such trials would not answer the primary epidemiologic question of this review. We did include trials focused on subspecialty populations for which the diagnosis and inpatient management of HTN were key outcomes.

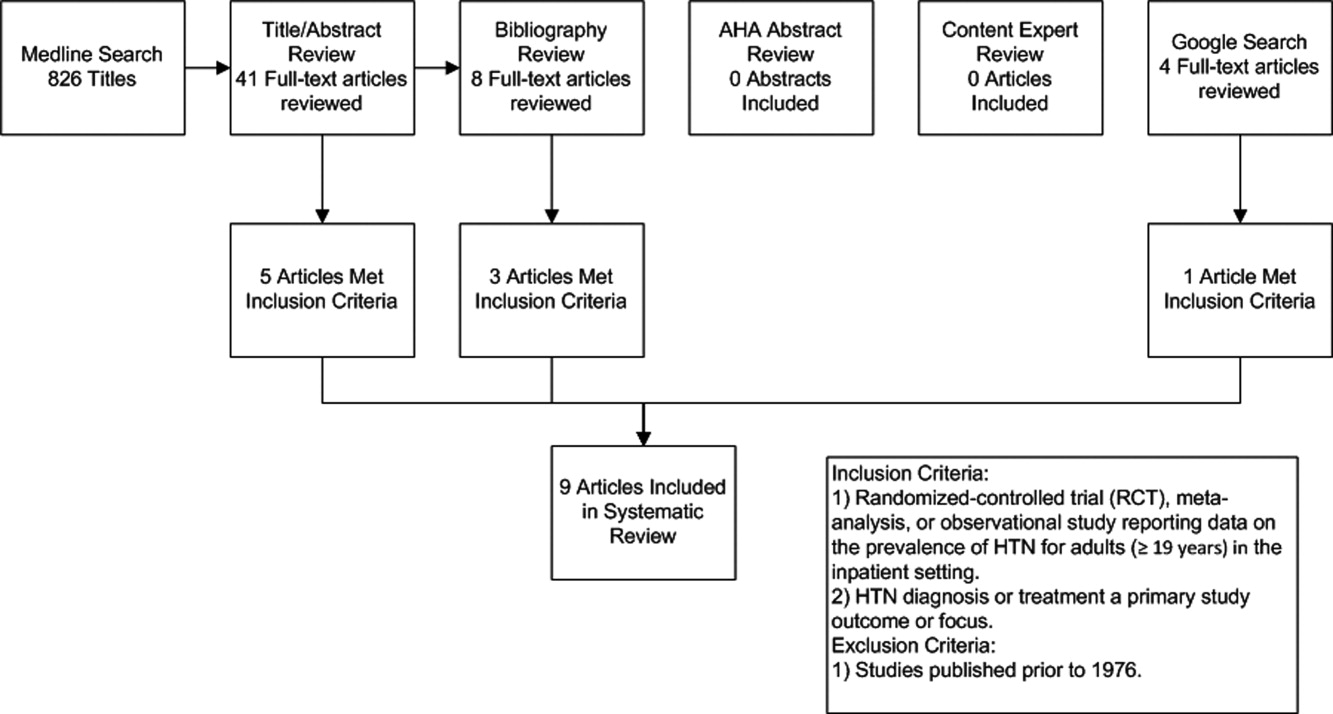

Next, the bibliographies of reviewed studies were investigated for additional relevant reports. Abstracts from the American Heart Association (AHA) were reviewed for the past 15 years for reports that were presented but not subsequently published and available in MEDLINE. We also searched for articles using the online Google search engine. One author (RNA) performed the preliminary MEDLINE search and abstract review with the assistance of a reference librarian (LC), and a second author (BME) also reviewed full‐text articles for potential inclusion. Ultimate decision for study inclusion was reached through discussion among authors. Finally, a list of potential articles was submitted to 2 experts in this field of study to determine whether other reports met our inclusion criteria for this systematic review but were overlooked.

Results

Search Results

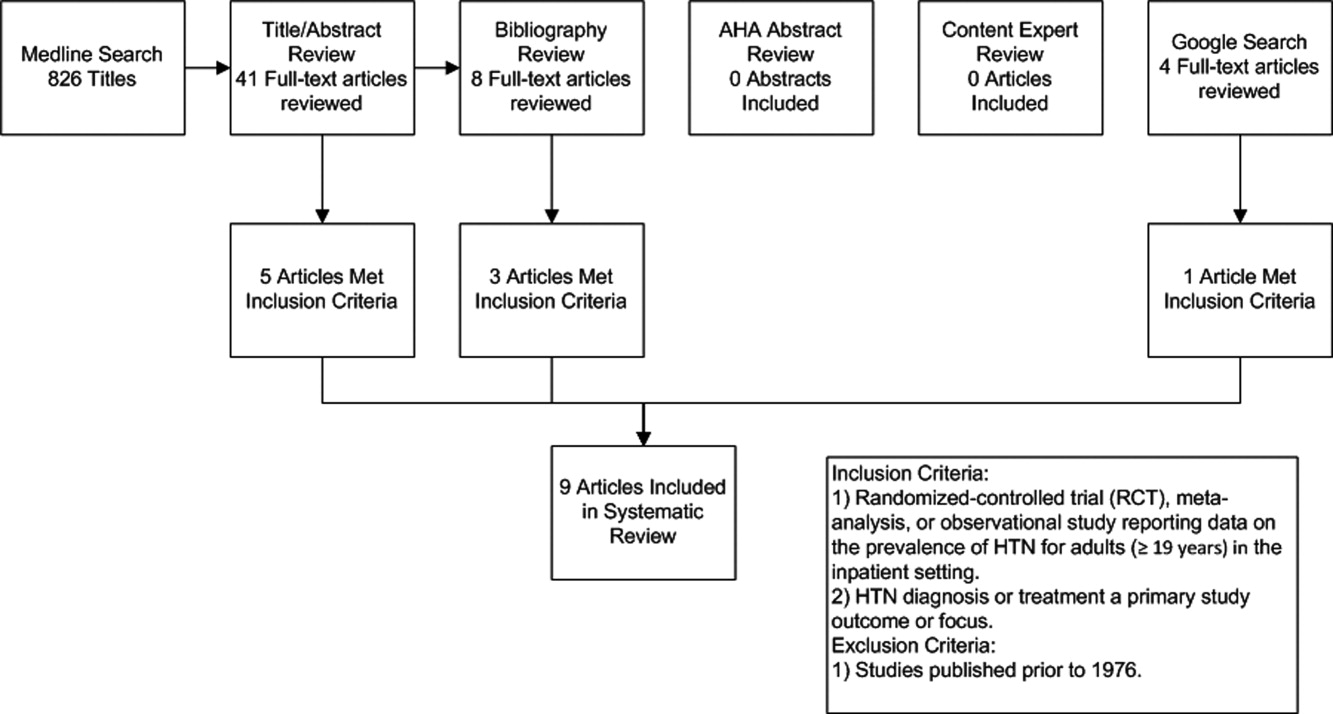

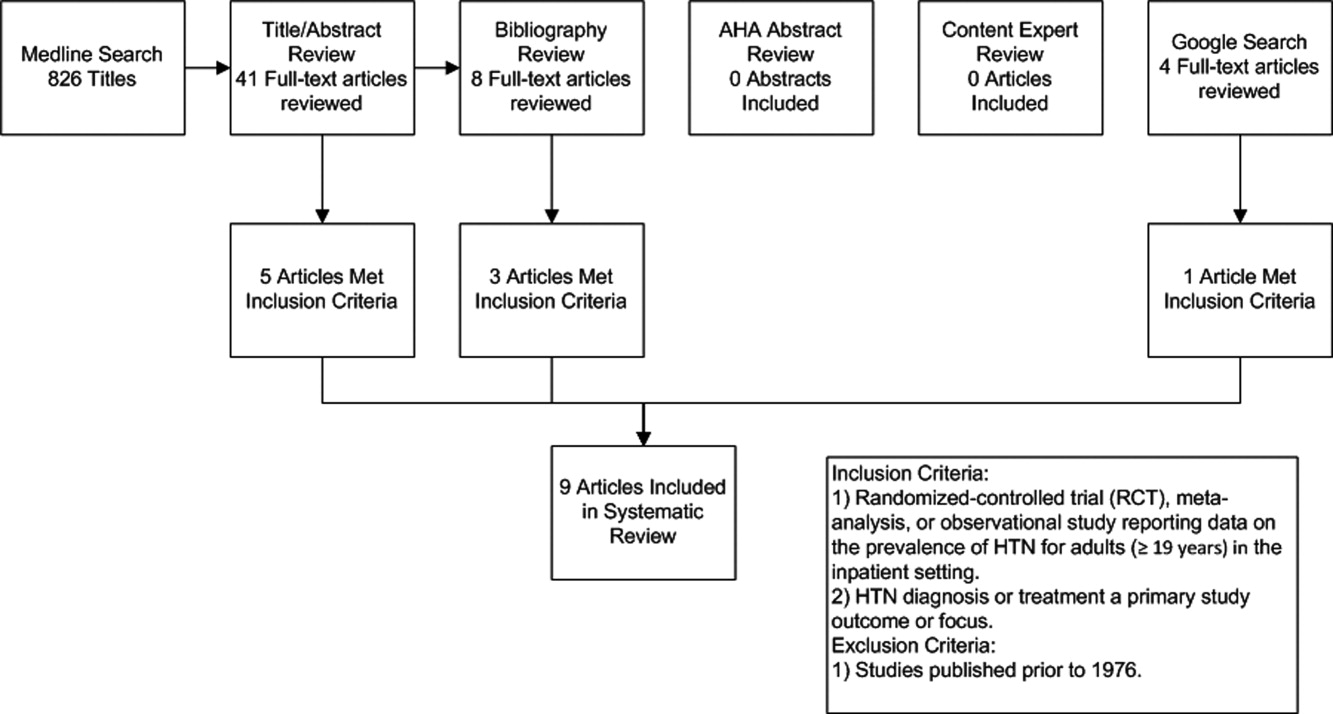

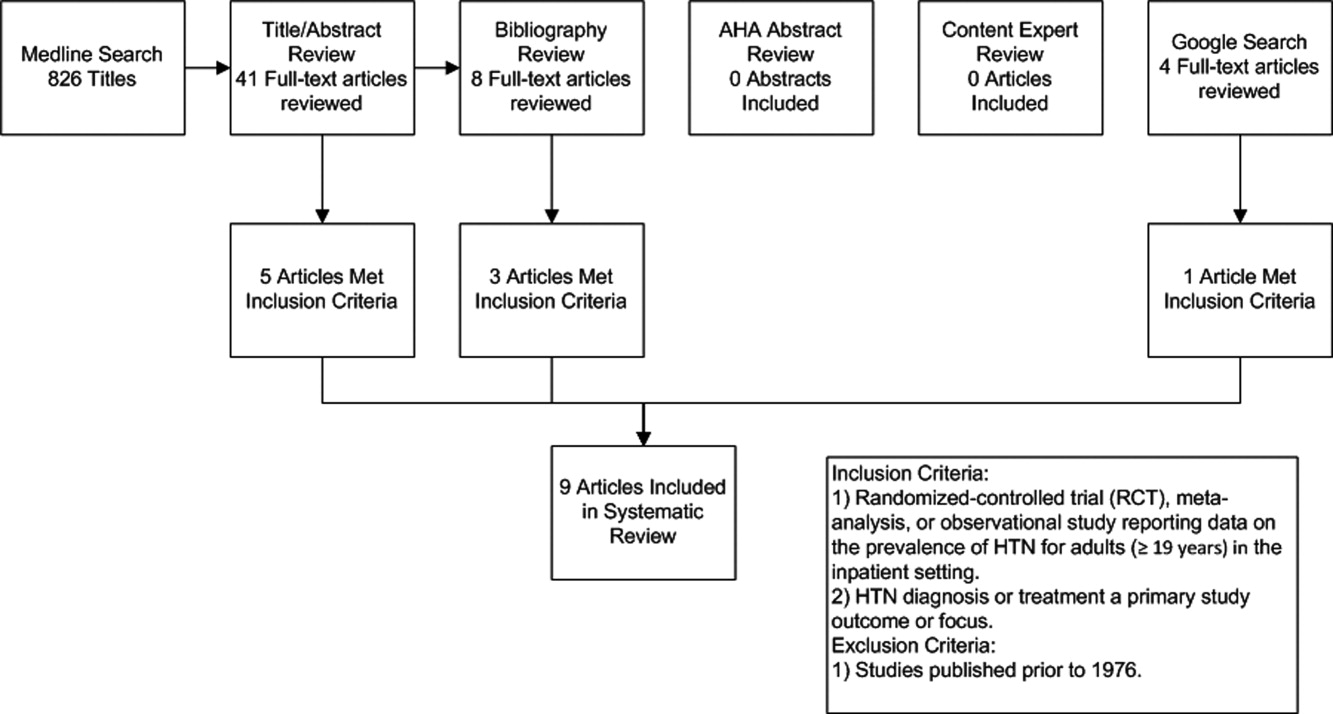

The initial MEDLINE search algorithm yielded a total of 826 articles. After title and abstract review, 41 full‐text articles were obtained for detailed review, and 5 met criteria for inclusion. Three additional articles were discovered through searching the bibliographies of the included studies. No AHA abstracts addressed this subject area. Experts were not aware of any additional studies. One article was located using a Google search. In all, 9 articles were deemed suitable for inclusion in this review. Search results at each stage are depicted in Figure 1.

Description of Included Studies

Characteristics of included studies are depicted in Table 1. Two older retrospective cohort studies reported HTN prevalence using earlier, less stringent diagnostic criteria. Shankar et al.15 abstracted data from more than 19,000 adults discharged alive from Maryland hospitals during 1978. Greenland et al.16 performed chart review for 536 medical and surgical inpatients in 1987 reporting information on the proportion of patients appropriately diagnosed as having HTN and the proportion with controlled BP on admission and at discharge based on then‐current JNC‐III criteria (HTN if BP > 160/90).

| Study | Design | Setting | Hypertension Prevalence | Diagnostic Criteria for HTN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Shankar et al.15 (1982) | Retrospective cohort | All hospital discharges in Maryland in 1978 | 23.8% (4571/19,259) | HTN diagnosis in record or diastolic BP 100 mm Hg |

| Greenland et al.16 (1987) | Retrospective cohort | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 28% (143/536 ) | HTN diagnosis in record or mean of first 4 hospital BP measures 160/90 mm Hg |

| Euroaspire I17 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 9 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 57.8% (2553/4415) | Admission BP 140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medications |

| Euroaspire II18 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 15 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 50.5% (2806/5556) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Amar et al.20 (2002) | Retrospective cohort | 77 Cardiology centers, France, ischemic heart disease admissions | 58.5% (729/1247) | HTN diagnosis in record or admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Onder et al.23 (2003) | Cross‐sectional | 81 Hospitals, Italy, elderly patients with known HTN | *86.9% (3304/3807) | HTN diagnosis in record AND admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Jankowski et al.19 (2005) | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 3 University cardiology centers, Poland | 70.2% (593/845) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Conen et al.21 (2006) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 72.6% (228/314) | HTN diagnosis in record OR mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Giantin et al.22 (2009) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, Italy, medical/surgical patients | 56.4% (141/250) | Mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Clinical Question | Findings |

|---|---|

| |

| Accuracy of routine inpatient BP measurements | 56.4% to 72.6% of inpatients receiving 24 hour BP monitoring had HTN.21, 22 |

| 28% to 38% of HTN patients had masked HTN (identified by 24‐hour monitoring but not revealed by routine inpatient BP measures). | |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled on admission | 86.9% of patients with previously documented HTN were uncontrolled on admission.23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled at discharge | 37% to 77% of inpatients with HTN still had BP > 140/90 mm Hg at time of discharge.16, 20, 23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients without a recorded diagnosis at discharge | 8% to 44% of patients with elevated BP > 140/90 mmHg were discharged without a documented diagnosis of HTN.15, 16, 18, 19 |

| Proportion of uncontrolled HTN patients receiving intensification of therapy during index admission | 53.1% of patients with uncontrolled BP received additional antihypertensive medication upon discharge.23 |

| Proportion of HTN controlled at follow up | 50% of patients with HTN were controlled to <140/90 mm Hg at follow up.17 |

Four studies focused primarily on cardiac patients. The European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (EUROASPIRE I) and subsequent EUROASPIRE II studies used retrospective chart review and prospective follow up clinic visits with a focus on baseline patient characteristics and risk factor modification at post‐discharge follow up.17, 18 Jankowski et al.19 studied 845 similar cardiac patients discharged from 6 Polish centers. Amar et al.20 performed a retrospective cohort study using records from 77 French cardiology centers to assess the impact of BP control prior to discharge in patients with acute coronary syndromes on the prevention of subsequent nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiac death.

Two studies utilized 24‐hour BP monitoring to diagnose HTN among inpatients, and compared this to routine inpatient measurement techniques. Conen et al.21 performed 24‐hour BP monitoring on 314 consecutive stable medical and surgical inpatients admitted to a Swiss University hospital. Giantin et al.22 also performed 24‐hour monitoring on a cohort of elderly Italian outpatients and inpatients to determine the prevalence of masked and white coat HTN in different care settings. Finally, Onder et al.23 reported on rates of uncontrolled BP and HTN management among known hypertensives as part of a series of cross‐sectional surveys performed on elderly Italian inpatients.23

Inpatient HTN Prevalence

Overall, study authors reported an HTN prevalence among inpatients that ranged from 50.5% to 72%. Estimates varied somewhat based on HTN definitions, diagnostic standards utilized, measurement techniques, and patient populations. In earlier studies HTN prevalence was reported at 23.8% to 28%, but these likely represented significant underestimates by current diagnostic standards.15, 16 High estimates by Onder et al.23 (86.9%) stem from selection criteria that included a prior billing diagnosis of HTN coupled with elevated admission blood pressures. Estimates in the 50% to 70% prevalence range were seen in studies that focused on cardiac and general medical inpatients.1722 Additional findings of included studies are listed in Table 2.

Accuracy of Inpatient BP Measures

In two studies, 24‐hour BP monitors produced prevalence estimates ranging from 56.4% to 72.6%.21, 22 In both studies, a significant proportion of patients had masked HTN, or HTN detected by 24‐hour BP monitoring alone. Also, 28% to 38% of patients without a prior HTN diagnosis, who were not detected by routine measures, were found to be hypertensive by 24‐hour monitoring. Finally, Conen et al.21 retested a subset of hypertensives with 24‐hour monitoring one month after hospitalization, and 87.5% remained categorized as hypertensive on follow‐up. Of note, it is unclear how this subset of patients was selected.

Proportion of Controlled HTN on Admission and Discharge

Because most included studies established prevalence of HTN based in part upon uncontrolled BP at hospital admission, estimates for the proportion of hypertensive patients controlled on admission were not given. However, Onder et al.23 did examine patients with a prior International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD‐9) diagnosis of HTN and uncontrolled HTN (BP 140/90) on admission. At discharge, only 23.2% of this cohort was controlled with a BP < 140/90 mmHg. However, other estimates suggested that 37% to 44% of patients remained uncontrolled at discharge.16, 20

Proportion of Undiagnosed HTN

In 4 studies, the proportion of patients with elevated BP and/or a history of HTN who did not receive a diagnosis of HTN upon discharge ranged from 8.8% to 44% between cohorts.15, 16, 18, 19 Interpretation of these estimates, however, is difficult due to significant differences between the studies. For example, both earlier studies were performed during an era of higher thresholds for HTN diagnosis and lower overall HTN awareness.15, 16 Both studies of cardiac patients suggested lower rates of nondiagnosis than might have been found in general medical or surgical inpatients.18, 19 One of the 4 studies also suggested that surgical patients who were hypertensive during hospitalization were more likely than medical patients to be discharged without a HTN diagnosis (17% vs. 4%, P < 0.05); although, the overall number of patients was small (18/146 remained undiagnosed).16

Proportion Receiving Intensification of Therapy

In 3 studies, prescribing practices for hypertensive inpatients were discussed. Shankar et al.15 found that only 62% of patients with a recorded HTN diagnosis received antihypertensive medications during hospitalization. Unfortunately, no information was given on the proportion of patients prescribed antihypertensive medications at the time of discharge. However, Greenland et al.16 found no net increase in BP medication use at discharge compared to admission despite 44% of patients remaining uncontrolled to <160/90 mmHg at the time of discharge. Onder et al.23 determined that BP medication was intensified in only 53.1% of hypertensive patients during hospitalization. Younger age, fewer drugs on admission, lower comorbidity index, diagnosis of congestive heart failure, lengthy hospital stay, and increasing levels of BP (systolic and diastolic) were all associated with more aggressive prescribing practices. Interestingly, Jankowski et al.19 found that treatment with a BP lowering agent at discharge was associated with the lowest odds of nontreatment at follow up (odds ratio [OR] 0.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.030.19).

Proportion of HTN Controlled at Follow Up